Abstract

In this paper, we analyze the gender issues that are present in the accounting profession, and more precisely, on the career paths one could follow in the accounting profession and what the underlying reasons are for each option. Our conclusions show that some of the factors that influence women career paths are discrimination, motherhood, glass-ceiling, double standard and a lack of visibility.

1. Introduction

Professions such as lawyers, engineers, architects, doctors (liberal professions) have at least one aspect in common—the common trait of conservatism. The accounting profession, also a liberal profession, is no exception. This is precisely why gender issues linked to the accounting profession are a subject of interest and their very existence in accounting organizations is no surprise. There have been studies and early contributions that attested to the gendered nature or accounting organizations (Kirkham and Loft 1993; Loft 1992; Lehman 1992; Fogarty et al. 1998; Grey 1998; Ud Din et al. 2017). Using these studies as a benchmark and a starting point, later on, other contributions to the literature emerged, mostly empirical studies of gender in accounting organizations (Anderson-Gough et al. 2005; Ciancanelli 1998; Dambrin and Lambert 2008, 2012; Lupu 2012; Kornberger et al. 2010; Mueller et al. 2011).

The aim of the study is to identify which are the main gender issues women face in the accounting profession and in the different career paths that one can choose to follow. For this, a qualitative approach was used, by conducting a literature review of articles on the topic of women in the accounting profession and also articles that mentioned the possible challenges one may face if they were to follow one certain career path. There are no similar studies conducted in the literature that would approach the aforementioned subject, which is precisely why the paper is a novelty. At the same time, it also addresses an existing research gap, which is the motivation behind approaching this area of research.

The type of literature review that was pursued in what follows was a structured one (Massaro et al. 2016) since it was based on carefully selected keywords from the approached area of research; a sample of relevant materials that would suit the purposes of the paper were chosen. In doing so, the paper provides answers to two major research questions:

- -

- Which are the main career paths in accounting?

- -

- What are the underlying reasons for the existence of glass ceiling and gender stratification inside accounting organizations?

In regards to the years taken into consideration when selecting articles, there was not a time span that was pre-considered, nor only a certain period in time. The keywords used were an important, and deciding factor regarding why some articles were considered and some were not. What is specific for this research is the fact that the analyzed articles come from a wide range of publishing years.

One of the first discoveries was that, from all the career paths one could follow in the accounting profession, the most disputed one, gender- and otherwise, was the auditing one. In the literature the most disputed career path is choosing to work in a Big Four (the four large accounting firms specialized in worldwide services such as audit and finance, business and financial advisory) thus the focus was mainly on studies that were approaching the Big Four. A second result of this paper was the realization that gender discrimination has as one of the major underlying reasons, motherhood, which is represented as a drawback in the case of career advancement and influences the extent of the heaviness of glass ceiling in those organizations.

The results of the paper are structured in three parts. The first part includes the used theories, such as gender stratification and the related notions such as double standard and glass ceiling. These theories are also explained and demonstrated using the Big Four case as an example. The second part includes the most common gender issues that can be associated with working in a large auditing firm based on the findings in the literature, and that influence the women to leave Big Four and start their own businesses, or to change employer even to continue in another audit and/or accounting firm or to change the environment by working in a company as a CFO, internal controller, internal auditor or other similar positions. The main contribution of the paper is the application of gender theories to carrier path issue by using sources from the literature. This usage of theories has led to the discovery of the underlying factors that are the cause of the impassibleness of breaking the ceiling.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. In the next section, the methodology will be presented, followed by presenting the main career paths in the accounting profession and by elaborating upon the main gender issues in the accounting profession. The last section concludes the paper.

2. Gender Stratification Theory

Gender stratification theory can be applied to a large range of situations (Brinton 1998; DuBose 2017; Blumberg 1984; Keister and Southgate 2012) and conditions including historical comparisons (Scott 1986; Wermuth and Monges 2002). Gender stratification can be used to explain the problems of building a theory that contains numerous factors which are directly linked.

The theory debates about a social ranking of some sort, where men typically inhabit a higher status than women. Gender stratification and gender inequality are the same facets of one idea. Gender stratification considers criteria as class, race, and sex (male/female). One of the things the theory suggests is that gender stratification exists to create in an efficient way, a division of labor or a social system in which a segment of the population oversees certain parts of labor, while the other segment is responsible for different parts that can be more important or not (Collins et al. 1993).

It analyzes all the aspects of the social life and cuts across social classes concerning the unequal access of men and women to power, prestige, and property all based on nature of their sex (Treas and Tai 2016; Collins et al. 1993).

Linked to the theory are concepts such as differential access, glass ceiling, and occupational distribution. The differential access refers to the fact that men have greater access to the labor market than women do, or that if they still do enter the labor market, they are doing it for lower paid jobs, or they have to periodically leave. The occupational distribution refers to the kind of work an individual does, work that can place him in a certain category or provide him with a certain label. The glass ceiling theory emphasizes upon the idea that it is harder for women to break through that ceiling which can lead them towards the upper level of organizations—a vertical promotion (Treas and Tai 2016; Collins et al. 1993).

From a sociological point of view, gender stratification is regarded as a theory proposing the existence of gender inequalities as a means to create a system, a social one, inside which one part of the population bears the responsibility of certain labor acts while the other part is responsible for other labor acts. Basically, the inequalities that have as a source gender, exist to create differences in the degree of responsibilities; the main issue is that there is a tendency, as in any other social group, for one group to become dominant and maybe suppress the other one (Treas and Tai 2016; Collins et al. 1993).

If conflict theory, which claims that society is in a state of continuous competition over resources (theory suggested by Karl Marx) (Collins 1990; Joas and Knöbl 2011) is introduced in relation to gender stratification theory, then it can be argued that gender can be understood as men overpowering women and trying to hold on to power and privilege, since society is defined by the on-going fight for dominance. In the case of gender, the dominant group are men and the subordinate group are women, which goes back to the two laborer categories. In time, the dominant group can change, but in most cases it does not, because the dominant group will always work and try to hold on to power. And this led in many cases, at least in the early days when women’s rights were almost nonexistent, to social change and uprisings (Collins et al. 1993).

Gender stratification theory or social stratification and gender, how it is also called in the literature (Grusky and Szelényi 2011; Grusky and Weisshaar 2014) emphasizes creating layers inside society, and how always one layer will be powerful than the other; if we put together gender and the theory of stratification, from this equation we get that men are the more powerful layer, and women as a group, will always take a back seat to history and to the public scene or to positions of power; elements that are leading to this conjunction are glass ceiling (Cotter et al. 2001; Ragins et al. 1998; Davidson and Cooper 1992), sexism, prejudice, double standard, discrimination, and last and not least the point, the underlying element to all of the above: the assumption that men are superior to women (Treas and Tai 2016; Collins et al. 1993).

Inside an organization you may have some of the discriminating factors present as dominant ones, while the others might be less striking. In either case, to some extent they could all be noticed. Sexism for example is strongly linked to double standards; at first sight one might not recognize or understand what is referred to when discussing it, but sexism is most recognizable in situations where women avoid pursuing certain career paths because they are viewed to be more masculine and suitable to a man; the glass ceiling also applies, because if they do have the courage to enter into such a profession, they have trouble meeting the expectations (that are molded after a man’s image) and thus in most cases they have trouble with being promoted (Treas and Tai 2016; Collins et al. 1993).

3. Methodology

3.1. Literature Search Approach

The paper is a literature review, and from a methodological point of view, a thorough analysis of the literature available was conducted. The selection of articles started by searching in the databases (ProQuest Central, Springer Link, Emerald, EBSCO) using keywords such as accounting profession, gender issues, women in the accounting profession. One of the first discoveries was that from all the career paths one could follow in the accounting profession, the most disputed one, gender and otherwise, was the auditing one. So, the perspective was shifted and the key words changed to auditing, gender issues, Big Four, women, accounting profession and any combination of the aforementioned words. In the literature, the most disputed career path is choosing to work in a Big Four, thus the focus was mainly on studies that were approaching the Big Four case.

The approached methodology explained above is a structured literature review since we used keywords that would suit our research topic, and based on the returns, we eliminated the articles that did not suit our purpose. As compared to a traditional literature review, which would provide a broad overview of the research topic, a structured literature review is providing a high-level overview of the primary research and answers to one or multiple research questions.

Through the structured literature review the paper is trying to respond to the below questions:

- -

- Which are the main career paths in accounting?

- -

- What are the underlying reasons for the existence of glass ceiling and gender stratification inside accounting organizations?

3.2. Selection of Articles for Review

The search returned several results, but many of the articles contained just one or two of the keywords, and the content of the article was not relevant for the purpose of this paper. Their titles and abstracts were reviewed by one author for the relevance of the study. After these articles were overlooked a number of 80 articles remained. From these articles those who were approaching the subject briefly and who did not elaborate on gender issues were eliminated as well as the ones who were duplicates. A total of 33 articles met the criteria. Papers were included if they approached the subject of gender in Big Accounting Firms or gender in accounting, in general (Table 1).

Table 1.

Number of articles used.

The articles that were used for the literature review are published in 19 different journals, including Critical Perspectives on Accounting (CPA), Accounting, Organizations and Society (AOS), Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal (AAAJ), so journals that are specialized on the accounting area but also in journals that do not have a connection to it such as European Sociological review (ESR), Gender, Work and Organization (GWO) or Gender in Management: An International Journal (GMIJ). The Journals that are more inclined to publish in the area are CPA, AOS and AAAJ if we take a closer look at the outcome represented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Main articles used.

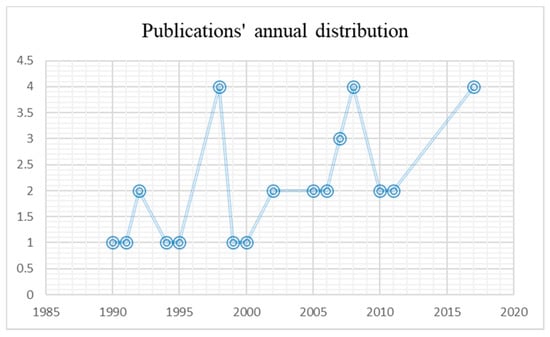

All the used articles were analyzed based on the year they were published, and the outcome is in the chart below where the trend can be noticed. The years 1998, 2008 and 2017 are seen as pique years (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Publications’ annual distribution, based based on selected articles. Source: author’s projection.

3.3. Development of Topics

The 33 articles that remained were analyzed based on the gender issues that they were approaching, in order to better review them and in order to have a logic in the discourse that was approached.

4. Results and Discussion

The section is divided in three parts. The first part is analyzing the career paths one could follow inside the accounting profession, with emphasis on Big Four accounting environment. Even if an approach where all possible career paths to follow were scrutinized, the literature provided mostly information regarding the auditing environment; thus, the focus of the research shifted.

The second part is looking into the glass ceiling phenomenon in the context of the aforementioned organizations and also as a primary component of the gender stratification theory. Lastly, the ultimate part is investigating the primary reasons for the existence of the glass ceiling, with a key finding of motherhood as a main and underlying component and factor.

4.1. Career Paths in the Accounting Profession

There are three main categories of career paths in accounting that one can follow after graduating, and all three of them refer to the idea of being employed. One of them is working in a Big Four company, the other refers working in a multinational and the last one working in a small practice as a bookkeeper.

Each one of these career paths has its own upsides and downsides, its requirements, its challenges and set of skills that are demanded. These requirements and challenges could be underlying factors that could influence the decision to follow that career path or not, or if already followed to explain the decision of choosing a different career path than the one initially chosen.

Accounting firms, and the major auditing companies in particular, often lose a considerable number of their new workers, as they choose to follow a different career path altogether after they leave. There is also a particular concern in these companies, about retaining women at higher levels of the hierarchy; it seems that even though women represent 50% of all entry level positions, 10 or 12 years later, the pool of women candidates is depleted (Greenhaus et al. 1997; Emery et al. 2002; Grey 1998).

The ones that choose the option of working in a Big Four company after that period of three to five years have several options: they remain in Big Four and advance on management positions, they go to one of their former clients in high level management positions, or they go to a multinational in management positions, or as a last option, they open their own business, since the know-how acquired is sufficient to ensure the business will not collapse.

The name of Big Four is given to a number of 4 firms that are specialized worldwide in services such as audit and finance, business and financial advisory, cyber, tax, governance, risk and regulation, property/real estate strategy and operations.

The group is comprised of PwC (PricewaterhouseCoopers), Deloitte (Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu), EY (Ernst & Young) and KPMG (Klynveld Peat Marwick Mitchell Main Goerdeler). They are called Big Four because they have a global presence, both in terms of size and reputation (Brock and Powell 2005; Perera et al. 2003; Builders of a Better Working World n.d.; The Big 4 Accounting Firms n.d.; The Big Four Accounting Firms n.d.; Small and Medium Practices n.d.).

One thing that is known about Big Four firms, even before one joins them, is that it is not a 9 to 5 job and that employees work very hard, sometimes even 70–80 h a week during the peak season to finish projects. It is the general trait for all 4 of them since all of them perform the same kind of work and the profile of the candidates is the same (Brock and Powell 2005; Perera et al. 2003; KPMG n.d.; Builders of a Better Working World n.d.; Deloitte n.d.; PwC n.d.).

Currently, each one of them is highly present in the professional services market and offering a wide range of services. For example, PwC is the second largest professional services firm in the world for the value of revenue, and third for the number of employees. Its headquarters is in the UK and the president of the company is Bob Moritz. The company has branches in 157 countries, with some 700 locations. The main focus of PwC is auditing and assurance services. They have the biggest number of clients from Fortune 100 and the largest audit fees from all the Big 4s (Brock and Powell 2005; Perera et al. 2003; KPMG n.d.; Builders of a Better Working World n.d.; Deloitte n.d.; PwC n.d.).

The impact that Big Four companies have on the markets is significant, considering that they are the ones that decide if the financial statements of one company are compliant or not, or if they accurate or not (Kirsch et al. 2000; Berger et al. 2000).

The majority of the literature is focused on Big Accounting firms, mainly because they have a special organizational structure, and the career ladder is visible and well structured. Furthermore, these organizations are very often compared with an escalator, precisely due to the speediness with which things are happening in terms of promotion and structure changes.

A job candidate can actually plan his or her career ahead and know what to expect in the future, and at least for the first few hierarchical levels, promotion comes quickly. To become a partner, one will have to be with the firm for a continued association of at least 13 to 14 years. Between the associate position and the partner position, there are nearly 6 more designations. Many firms have a policy of working at a particular designation for at least 2 to 3 years before getting promoted. Two years staff, three years senior (two years if you get promoted early), three years manager (two years if you get promoted early) and 3 to 5 years senior manager (where coaching for partnership begins) (Burrowes et al. 2004).

Generally, in all four of them, the structure remains the same and there are 4 levels for the professional staff (divided vertically into seniority grades), up until one can make it to the top to the role of partner: junior auditor, senior auditor, manager and finally partner (they are also divided in small other positions). For the role of junior auditors (junior audit associates) they usually recruit directly from the faculty and start preparing the new joiners for future higher roles (Burrowes et al. 2004).

A junior auditor will be responsible for up to three people and at first will be assigned small and medium sized client assignments; after acquiring more experience, they will be involved in various clients’ assignments and they are directly reporting to the senior audit associate. A senior audit associate is involved in major client’s assignments and has a bigger staff responsibility and directly reports to the junior audit manager. A junior audit manager is responsible with a large team of staff and major clients’ assignments, they report back to the senior manager, who is responsible for the entire department and with almost all the clients of that department (Baker and Hayes 2004).

The last hierarchical step is Partner, to which a senior manager reports. A partner is in charge of the development of clients, bringing more clients and satisfying their requirements. Partners, delegate decisions of routine management to the managing partners (senior audit managers). They are responsible for the service they are providing to the clients, even though the managing partner is the one in charge of the whole audit mission, including the staff (Burrowes et al. 2004).

Aside from the vertically division there is a lateral one, dividing the staff into departments: audit, taxation, legal, consultancy, liquidation. The professional staff together with the partners maintains accurate time records, meaning that they will track how much time a certain activity took, since the Big Four companies bill their clients at hourly rates. They have to be able to justify the bill and moreover, to accurately bill the clients (Baker and Hayes 2004).

Regarding women’s presence in Big Four companies, a recent study by Catalyst (January, 2018 citing Financial Reporting Council) showed that, contrary to the reality of over 50% females in the accounting profession, in the Big Four companies, the number of women principals (partners) is below 20%, EY 19% (highest rate), PwC 17%, Deloitte-15% and KPMG-15%. The same study revealed that, as stated before, women were 50.2% of all auditors and accountants and that the proportion of women studying accounting worldwide has increased up to 49%. Moreover, the gender pay gap is still a problem and that women working as auditors and accountants are paid $1600 less per month than men with the same job and responsibilities.

Since an overwhelming number of studies about career paths in the accounting profession are focusing on the Big Four environment, it explains why the review is done on articles that are focusing on the topic. Even though we identified multinationals and small accounting practices as the other two career paths, they were not included, because the studies based on them were not sufficient.

4.2. Glass Ceiling as a Part of Gender Stratification Theory

In the literature, there are a number of studies focusing on Big Four accounting firms and gender stratification implications in their work culture. It only serves to prove that whatever happened in the past in terms of gendered issues for women, continues in the present. These issues never disappeared, nor did they surface only recently. They were there since the beginning of time, since women entered the profession, and they will continue to be present.

Glass ceiling represents the invisible barrier that prevents women and minorities from climbing up the hierarchical ladder. It is a metaphor used to represent an invisible barrier that keeps a certain demographic from rising beyond a certain level in a hierarchy. In the case of women breaking the barrier, this would imply their efforts are recognized by their superiors, who in most cases happen to be men (Smith and Caputi 2012; Helfat et al. 2006).

The work hours in a Big Four firm are modeled after the client’s program and often, in order to complete audit missions and projects, employees work 70–80 h per week; which is considerable, and not very flexible. With a job that demanding, it is difficult to find balance between work life and personal life. One must suffer. And the question is who is willing to make sacrifices?

The studies focus on glass ceiling theory and gender inequality at work for women in particular. There are several studies in the literature that approach the subject of women inequality at the work place, but more precisely, the effects of the gender stratification theory in Big Four companies (Lupu 2012; Kornberger et al. 2010; Dambrin and Lambert 2008; Duff 2011; Anderson-Gough et al. 2005; Anderson-Gough et al. 2002).

These Big Four accounting firms were and are the subject of numerous studies because of the style of working, which is entirely and utterly different from any other workplace. Of course, every work environment is different and has its own particularities, but when it comes to Big Fours, it’s an entirely different story. Why? First of all, due to the long hours that employees pull and second of all, due to strict requirements one must meet in order to be able to join such a company.

One of the papers that investigate the glass ceiling theory and the case of women in Big Fours is written by Lupu (2012). The article focuses on the accounting profession in France and depicts the work environment and the way women were treated in these firms.

Regarding the accounting profession in France, in the early beginnings of the profession the presence of women was rare, similar to many other countries (Dambrin and Lambert 2008; Lupu 2012). Female public accountants were hard to find and the situation remained like that up until 1980 when women started to be more present in the profession. The presence increased from 9% in 1980 to 19% in 2010, but compared to other French professions, the process of feminizing the accounting process is lagging (Lupu 2012).

The same phenomenon can be seen in the Big Four companies where at the moment the study was made, women partners in all the firms in the country, were between 10% and 18%. There are certain approved routes when it comes to career paths that are already in place and that are acknowledged. And these career paths are modeled after the image and skills of men, meaning they are more suitable for men (Duff 2011; Anderson-Gough et al. 2005; Lupu 2012).

It is also brought to discussion that if one were to propose some alternative paths, these routes would not have the same impact as the paths that were already approved because they would lack legitimacy and would derail women careers from early on. Basically, the approved routes of the career paths are gendered and biased (Duff 2011; Anderson-Gough et al. 2005).

There are two theories that explain the lack of women in the higher ranks of organizations. The first theory was developed by Catherine Hakim, and is called the preference theory, preference between market work and family work. Hakim argues that in order to find the reasons for the presence of women in inferior positions rather than in higher ranks, it is necessary to look for factors that are dispositional and not functional, meaning for example, the nature of their work (Hakim 1991; Procter and Padfield 1999).

Hakim (1991) argues that the choices one makes career wise (and other choices) are influenced by the lifestyle preferences one has. She creates three categories of people called home centered, work centered or the ones that show adaptive lifestyle preferences. Hakim argues that the latter who want to reconcile the work life with the family life will not give priority to work life. That is precisely what is required to get to the top levels of an organization, namely, giving priority to work. Thus, women who wish to balance they work life with their family life will never make it to the top. It was also reinforced by Procter and Padfield (1999).

Basically, the bottom line is that the rarity of women at top levels is explained by the choice women make to prioritize family over work, period. There are others that argue against the idea, suggesting that women are as focused on their careers as men are, and they want promotion as much as men do.

The second theory that could explain the rarity of women in top positions could be the influence of social and organizational context and the influence of stereotyping that makes it hard for people in general to take roles that are in different register from what it was prescribed to them (Lehman 1992; Duff 2011; Hakim 1991).

Earlier there was mentioned the reasons one would like to follow a career in a Big Four company and why the Big Four environment is so appealing to researchers. There are other similar arguments that these large firms, even though difficult to access information, have a professional culture which is based on processes and practices that are highly standardized, have a transparent hierarchical structure and the career model is based on “up or out” model. The career model basically means that those deserving of promotion, are given it. It is considered that accounting practices are shaped in these Big Four companies that they are regulated here (Lyonette and Crompton 2008; Kornberger et al. 2010).

Statistical data in a study published in 2011 shows that the highest percentage of women as partners in a Big Four company could be found at Deloitte and KPMG, 18.8%, in the United States, while PwC had the lowest rate, only 16.9%. By comparison in France, the ranges varied form 10% (KPMG) to 18% (PwC) (Lupu 2012).

4.3. Gender Issues that Influence the Women Carrier Paths in the Accounting Profession

4.3.1. Double Standard in Career Advancement and Recruiting

In terms of recruitment, what Lupu (2012) has discovered in her research is that first of all, that Big Four companies (in France) had a habit of recruiting amongst the candidates that graduated only from Grandes Ecoles, because they were considered to be elite places with prepared candidates who had un upper hand, in comparison the graduates from other schools: they could pick up on things faster, write better, progress better. They had other skills that the candidates from other places did not, skills that were more valuable than knowing accounting, which was considered something that could be easily learned. One additional factor that was considered, was that these graduates were coming from good families, and thus ten years later, they could bring clients in the firm by using their familial connections.

Recruiting from Grandes Ecoles ensured a homogeneity of the candidates because they would have the same behavior, same profile that would fit the firm’s values and culture. The firm had little or no work to do when it came to “formatting” the recruits to the highly formalized culture. A different aspect when it came to recruiting discovered through the interviews was that even though the Big Fours wanted to seem gender balanced, in reality, the situation was not like that at all (Lupu 2012).

Women had a better academic situation than men, but this was not taken into consideration. The partners who recruited were told to be a little bit harder on women because otherwise there would have been more women in the organization than men, and that would not have been okay when they would go on maternity leaves. It would have affected an entire generation. One of the interviewees said that if they would have been fair to all candidates during the interviews, and they would have disregarded the gender. Currently, the situation would have been very different because women’s records were far better than men’s (Anderson-Gough et al. 2005; Grey 1998).

The career path and advancement in a Big Four is far more stringent than in any other companies; it can be compared to an escalator that it is always moving, and if you step out for just a bit then you will be surpassed by your colleagues and the entire work scene will seem different when you get back (for example maternity leave in the case of women) (Mueller et al. 2011).

In some studies, the Big Four environments are described as a workplace that is very demanding, where work never stops nor does the rhythm. However, employees do not seem to be bothered by it since they see it as a competition with their peers who were often their college mates. So inside these firms, there is a cohort effect created, that makes it okay for the staff to leave work at 11 because they have the feeling of belonging to a group, to a team with people that have the same age (Anderson-Gough et al. 2005; Lehman 1992).

What it seems conventional inside the Big Four firms (crazy rhythm of work, long hours, huge workload, becoming better, more efficient, working harder to be able to promote) it is tough to understand for people who have never worked in such a place. And here comes the differentiating factor for women, namely that they relate to time differently than men do, they have to fit in the same amount of time more activities and that is why they will allocate less time to networking activities than men will; just because they have to deal with personal matters, they do not have the luxury of spending their free time networking (Anderson-Gough et al. 2005; Duff 2011; Lehman 1992).

The consequence of the double responsibility is that the career of women often takes a different turn when they have children. They temporarily leave the work environment, the time during which their male colleagues are promoted and the whole dynamic at work changes, and the whole hierarchical structure. The idea of working hard in a Big Four firm is only bearable because at the end of the day one knows that eventually he/she will be promoted. But when you reach the end of the hierarchical ladder and you are not considered as partner material, it is hard to accept, and many leave (Lehman 1992).

4.3.2. Motherhood as a Primary Gender Issue

Motherhood came up several times during the interviews and it was one of the reasons why women were excluded from the path of reaching partner or excluded themselves since they were preoccupied with other matters and work was not their main focus anymore. Advancing with the interviews, the authors discovered three main reasons that led to the rarity of women in higher ranks of organizations. The first one is that the audit firms are the ones that, through their policies and practices, are pushing women away and do not give them the same opportunity.

The second one is the exact opposite; women start to separate themselves from “the crowd” in anticipation of the event and to try to reconcile both private and professional life. The third one is in direct link to the second one, a direct consequence, an aftermath, and it refers to the idea that struggling to make peace between personal and professional life women often choose a different professional path, that is different from what the rest of the colleagues are doing and which is not in accordance with the organizations practice. That path alienates them from the highest levels, thus the rarity of women in higher ranks (Mueller et al. 2011; Crompton and Sanderson 1990; Loft 1992).

What it means to work in an audit firm was detailed earlier, based on Lupu (2012) article, which described the job requirements in the context of French firms. Grey (1998) also explains the bottom line of what it means to be an auditor in a Big Four firm is that is it a career model is “up or out”, a model that is for all employees and which has as an ultimate goal the partnership of the firm.

In auditing, the system is that employees work on teams on different clients and the competition between teams is very high. Each team has a junior, a senior and a manager. The fees for auditing are established with the client and highly negotiated before the audit mission started. The firm is on a budget, and the idea is to be productive and efficient. That is why managers tend to maximize the productivity of the teams by belittling the amount of work they perform. And they continually ask for more and more effort. The employees are also made accountable in front of the clients, creating a relationship with the client from the smallest member of the team. At the end of all of these lies the possibility that if you make partner, you can earn a percent of the profit, but also the risks of signing off on the audit opinion and bearing the responsibility.

It is precisely why motherhood will never be a good fit in an audit company, because it represents everything that and audit firm would want to avoid, since becoming a mother means that that person will be missing for a longer period from the firm and will be disconnected from everything (clients, networking, colleagues) (Carnegie and Walker 2007; Johnson et al. 2008; McKeen and Richardson 1998).

Pregnancy, according to the statements given by the interviewees, when it is announced, is not seen in favorable light, especially if it is in the busiest work season. One of the women interviewed stated that if you announce a pregnancy during the audit season and you do not plan it for the summer, it means that you have done it on purpose and that somehow you are announcing your resignation. A downside brought up by several women was that often, after announcing a pregnancy, they would get their bonuses cut even though many of them still work the same hours as before, and they are passed over for promotion that year (Dambrin and Lambert 2008; Spruill and Wootton 1995).

Furthermore, during the period she is missing, her client portfolio gets transferred to another member of the organization, and the clients that are big and represented the best assignments are the ones that go first (the clients that are the most prestigious and most comfortable to work with). A woman in that situation loses all her visibility in the firm and all the pre-acquired knowledge that made her visible in the organization (Charron and Lowe 2005; Johnson et al. 2008).

Nevertheless, there are still some barriers that could be considered as being glass ceiling barriers and taken into consideration, such as the fact that the director position is occupied by women in a proportion of 60% because it is the end point of their careers in a Big Four. The level is dedicated to those who were senior managers for a long time and who will never make partners (Ciancanelli 1998).

These spots are usually reserved for people who do not have the skills to search for clients, or negotiate fees. Described above are different forms of discrimination women are subjected to once they announce their pregnancy. But how do they cope with work and maternity? According to Dambrin and Lambert (2008), they start organizing themselves in time to be prepared for the future. They start delegating their assignments and make sure they choose the right persons to do that, to be able to recover their clients once they get back (Reed et al. 1994).

The second way women try to manage motherhood in their work life is by imposing different work habits on their team, such as starting work earlier, taking no breaks, including lunch break and finishing work earlier by a certain time. These work practices that are imposed are not necessarily received without backlash since basically, these women are imposing crazy deadlines with the same workload as before (Barker and Monks 1998; Lehman 1992).

One other option would be that they choose to specialize in certain areas such taxation, that will make developing expertise easier, and more importantly, will make juggling their personal life with work life easier, since they do not have to travel anymore and go on assignments. Nevertheless, the role of an expert is difficult to be left, and usually, when a woman becomes an expert she remains there and is automatically separated from the prospect of becoming a partner. Aside from the expert position, a different one is the one of the support function, meaning that women leave their branches as auditors and go, in most cases in the human resources department. For both of these positions, it is not impossible to become partner; there are cases, but it is harder and rare (Barker and Monks 1998; Kornberger et al. 2010; Lehman 1992).

The conclusion of the study is that if women choose to favor their pregnancy over the work life, they gain no recognition and are offered positions that mean that they will not advance to be partners. There are women who make it as a partner, but they are not viewed as a true partner, not like men are seen, precisely because they still have families to deal with (Dambrin and Lambert 2008).

The bottom line is that these accounting organizations are gendered through their policies and practices. At first sight, they may seem to be conventional and neutral because it is standard to have promotion procedures and performance indicators and reviews. But at a second glance, one may discover that they are indeed gendered since they are modeled after a man’s profile or that it fits better to a man than it fits a woman (Kornberger et al. 2010; Anderson-Gough et al. 2002). When it comes to how things can be changed, nobody takes the initiative.

5. Conclusions

The article intended to discover the gendered issues one may have, in current times, when choosing a certain career path. The paper focused on gender issues women currently face in the accounting profession. The first intention of the paper was to analyze all possible career paths in the accounting profession and to find what the reasons are behind choosing a certain career path or not, as well as the gender issues one may face when pursuing that particular career path.

Based on the findings of the article, we draw two conclusions: the first part is comprised of the actual career paths we were able to analyze and the second part the gender issues one may face with the underlying reasons and as well the solutions that were found.

The first part of the findings reveals that the most disputed career path in the literature is working in a large auditing firm. The other career paths such as small accounting firms or multinationals are not investigated to any extent. They did not pose interest to researchers neither from a gendered perspective nor from an organizational perspective. This is a gap in the literature and can constitute the agenda for future research. When more papers that would approach the subject of the other career paths in the accounting profession is available in the literature, then another possible agenda for future research would be a comparison between career paths and the gender issues they face.

The second part of the findings is comprised of the gender issues women face in large auditing firms and one of the most important discoveries is that gender discrimination is very much present through glass ceiling phenomena, double standard, motherhood and the aftermath that comes with it. The findings showed that motherhood is an important reason why women do not advance to partnership as easily or fast as men, or that it is okay for a man with a family to consider his job a priority, but it is not okay for women.

The main contribution of the paper is the application of gender theories to career path issues by using sources from the literature. This usage of theories led to the discovery of the underlying factors that are the cause of the impassibleness of breaking the ceiling.

The overall findings revealed that breaking through the ceiling and overcoming all of the obstacles in the way of reaching the top level, for women, is still difficult and this may be the cause for some of them to decide to try to be independent and become entrepreneurs.

Entrepreneurship is not the only possible solution to the glass ceiling phenomenon and gender discrimination in accounting organizations; a more proactive attitude in trying to accommodate solutions in order to prevent or diminish the impact of it, can be the answer as well and this is a limitation of the current research.

Author Contributions

The authors’ individual contribution are the follows: A.T.-T., part 1, 2 and 5 and W.A.F., part 3 and 4.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Anderson-Gough, Fiona, Christopher Grey, and Keith Robson. 2002. Accounting Professionals and the Accounting Profession: Linking Conduct and Context. Accounting and Business Research 32: 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson-Gough, Fiona, Christopher Grey, and Keith Robson. 2005. “Helping them to forget”: The organizational embedding of gender relations in public audit firms. Accounting Organizations and Society 30: 469–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, C. Richard, and Rick Hayes. 2004. Reflecting form over substance: The case of Enron Corp. Critical Perspectives on Accounting 15: 767–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, Patricia C., and Kathy Monks. 1998. Irish women accountants and career progression: A research note. Accounting, Organizations and Society 23: 813–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, Allen N., Robert DeYoung, Hesna Genay, and Gregory F. Udell. 2000. Globalization of Financial Institutions: Evidence from Cross-Border Banking performance. Brookings-Wharton Papers on Financial Services 1: 23–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumberg, Rae Lesser. 1984. A general theory of gender stratification. Sociological Theory 2: 23–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinton, Mary C. 1998. The Social-Institutional Bases of Gender Stratification: Japan as an Illustrative Case. American Journal of Sociology 94: 300–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brock, David M., and Michael J. Powell. 2005. Radical strategic change in the global professional network: The “Big Five” 1999–2001. Journal of Organizational Change Management 18: 451–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Builders of a Better Working World. n.d. Available online: http://www.ey.com/gl/en/about-us (accessed on 20 January 2018).

- Burrowes, Ashley W., Joseph Kastantin, and Milorad M. Novicevic. 2004. The Sarbanes-Oxley act as a hologram of post-Enron disclosure: A critical realist commentary. Critical Perspectives on Accounting 15: 797–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carli, Linda L., and Alice H. Eagly. 2007. Overcoming resistance to women leaders: The importance of leadership style. In Women and Leadership: The State of Play and Strategies for Change. Edited by Barbara Kellerman and Deborah L. Rhode. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Carnegie, Garry D., and Stephen P. Walker. 2007. Household accounting in Australia: Prescription and practice from the 1820s to the 1960s. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 20: 41–73. [Google Scholar]

- Charron, Kimberly Frank, and D. Jordan Lowe. 2005. Factors that affect accountant’s perceptions of alternative work arrangements. Accounting Forum 29: 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciancanelli, Penny. 1998. Survey research and the limited imagination. Critical Perspectives on Accounting 9: 387–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, Randall. 1990. Conflict theory and the advance of macro-historical sociology. In Frontiers of Social Theory. Edited by George Ritzer. New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 68–87. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, Randall, Janet Saltzman Chafetz, Rae Lesser Blumberg, Scott Coltrane, and Jonathan H. Turner. 1993. Toward an integrated theory of gender stratification. Sociological Perspectives 36: 185–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotter, David A., Joan M. Hermsen, Seth Ovadia, and Reeve Vanneman. 2001. The Glass Ceiling Effect. Social Forces 80: 655–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, Rosemary, and Fiona Harris. 1998. Explaining women’s employment patterns: ‘Orientations to work’ revisited. The British Journal of Sociology 49: 118–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crompton, Rosemary, and Kay Sanderson. 1990. Gendered Jobs and Social Change. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Czarniawska, Barbara. 2008. Accounting and gender across times and places: An excursion into fiction. Accounting, Organizations and Society 33: 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dambrin, Claire, and Caroline Lambert. 2008. Mothering or auditing? The case of two Big four in France. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 21: 474–506. [Google Scholar]

- Dambrin, Claire, and Caroline Lambert. 2012. Who is she and who are we? A reflexive journey in research into the rarity of women in the highest ranks of accountancy. Critical Perspectives on Accounting 23: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, Marilyn J., and Cary L. Cooper. 1992. Shattering the Glass Ceiling: The Woman Manager. London: Paul Chapman Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Deloitte. n.d. About Deloitte. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/global/en/pages/about-deloitte/articles/about-deloitte.html (accessed on 20 January 2018).

- DuBose, Renalia. 2017. Compliance Requires Inspection: The Failure of Gender Equal Pay Efforts in the United States. Mercer Law Review 68: 445–60. [Google Scholar]

- Duff, Angus. 2011. Big four accounting firms annual reviews: A photo analysis of gender and race portrayals. Critical Perspectives on Accounting 22: 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emery, Michelle, Jill Hooks, and Ross Stewart. 2002. Born at the Wrong Time? An Oral History of Women Professional Accountants in New Zealand. Accounting History 7: 7–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fearfull, Anne, and Nicolina Kamenou. 2006. How do you account for it? A critical exploration of career opportunities for and experiences of ethnic minority women. Critical Perspectives on Accounting 17: 883–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogarty, Timothy J., Larry M. Parker, and Thomas Robinson. 1998. Where the rubber meets the road: Performance evaluation and gender in large public accounting organizations. Women in Management Review 13: 299–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gendron, Yves, and Laura F. Spira. 2010. Identity narratives under threat: A study of former members of Arthur Andersen. Accounting, Organizations and Society 35: 275–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhaus, Jeffrey H., Karen M. Collins, Romila Singh, and Saroj Parasuraman. 1997. Work and Family Influences on Departure from Public Accounting. Journal of Vocational Behaviour 50: 249–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grey, Christopher. 1998. On being a professional in a ‘Big Six’ firm. Accounting, Organizations and Society 23: 569–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grusky, David B., and Szonja Szelényi. 2011. The Inequality Reader. Contemporary and Foundational Readings in Race, Class and Gender. Abingdon: Routledge. Milton Park: Taylor and Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Grusky, David B., and Katherine R. Weisshaar. 2014. Social Stratification: Class, Race, and Gender in Sociological Perspective. Abingdon: Routledge. Milton Park: Taylor and Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Hakim, Catherine. 1991. Grateful slaves and self-made women: Fact and fantasy in women’s work orientations. European Sociological Review 7: 101–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joas, Hans, and Wolfgang Knöbl. 2011. Conflict sociology and conflict theory. In Social Theory: Twenty Introductory Lectures. Edited by Hans Joas and Wolfgang Knöbl. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 174–98. [Google Scholar]

- Helfat, Constance E., Dawn Harris, and Paul J. Wolfson. 2006. The Pipeline to the Top: Women and Men in the Top Executive Ranks of U.S. Corporations. Academy of Management Perspectives 20: 42–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewlett, Sylvia Ann. 2007. Off-ramps and on-ramps. In Keeping Women on the Road to Success. Brighton: Harvard Business School Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jeny, Anne, and Estefania Santacreu-Vasut. 2017. New avenues of research to explain the rarity of females at the top of the accountancy profession. Palgrave Communications 3: 17011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Eric N., D. Jordan Lowe, and Philip M. J. Reckers. 2008. Alternative work arrangements and perceived career success: Current evidence from the big four firms in the US. Accounting, Organizations and Society 33: 48–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keister, Lisa A., and Darby E. Southgate. 2012. Inequality: A Contemporary Approach to Race, Class, and Gender. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkham, Linda M., and Anne Loft. 1993. Gender and the construction of the professional accountant. Accounting, Organizations and Society 18: 507–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirsch, R.J., K. Laird, and T Evans. 2000. The Entry of International CPA Firms into Emerging Markets: Motivational Factors and Growth Strategies. The International Journal of Accounting 35: 99–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornberger, Martin, Chris Carter, and Anne Ross-Smith. 2010. Changing gender domination in a Big Four accounting firm: Flexibility, performance and client service in practice. Accounting, Organizations and Society 35: 775–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KPMG. n.d. KPMG 2017 Citizenship Report. Available online: https://home.kpmg.com/us/en/home/about.html (accessed on 20 January 2018).

- Lehman, Cheryl R. 1992. Herstory in accounting: The first eight years. Accounting organization and Society 17: 262–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loft, Anne. 1992. Accountancy and the gendered division of labour: A review essay. Accounting, Organizations and Society 17: 367–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupu, Ioana. 2012. Approved routes and alternative paths: The construction of women’s careers in large accounting firms. Evidence from the French Big Four. Critical Perspectives on Accounting 23: 351–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyonette, Clare, and Rosemary Crompton. 2008. The only way is up? An examination of women’s “under-achievement” in the accountancy profession in the UK. Gender in Management: An International Journal 23: 506–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macintosh, Norman B., and Robert W. Scapens. 1990. Structuration theory in management accounting. Accounting, Organizations and Society 15: 455–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, Joanne. 2000. Hidden gendered assumptions in mainstream organizational theory and research. Journal of Management Inquiry 9: 207–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massaro, Maurizio, John Dumay, and James Guthrie. 2016. On the shoulders of giants: Undertaking a: Structured Literature Review. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 29: 767–801. [Google Scholar]

- McKeen, Carol A., and Alan J. Richardson. 1998. Education, Employment and Certification: An Oral History of the Entry of Women into the Canadian Accounting Profession. Business and Economic History 27: 500–21. [Google Scholar]

- Mueller, Frank, Chris Carter, and Anne Ross-Smith. 2011. Making sense of career in a Big four accounting firm. Current Sociology 59: 551–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, Hector B., Asheq R. Rahman, and Steven F. Cahan. 2003. Globalisation and the major accounting firms. Australian Accounting Review 13: 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Procter, Ian, and Maureen Padfield. 1999. Work orientations and women’s work: A critique of Hakim’s theory of the heterogenity of women. Gender, Work and Organization 6: 152–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PwC. n.d. Our Purpose and Values. Available online: http://www.pwc.com/gx/en/about/purpose-and-values.html (accessed on 20 January 2018).

- Ragins, Belle Rose, Bickley Townsend, and Mary Mattis. 1998. Gender gap in the executive suite: CEOs and female executives report on breaking the glass ceiling. Academy of Management Perspectives 12: 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, Sarah A., Stanley H. Kratchman, and Robert H. Strawser. 1994. Job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and turnover intentions of United States accountants. The impact of the locus of control and gender. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal 7: 31–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, Joan Wallach. 1986. Gender: A Useful Category for Historical Analysis. American Historical Review 91: 1053–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small and Medium Practices. n.d. Available online: https://www.ifac.org/about-ifac/small-and-medium-practices (accessed on 20 January 2018).

- Smith, Paul, and Peter Caputi. 2012. A Maze of Metaphors. Faculty of Health and Behavioral Sciences 27: 436–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spruill, Wanda G., and Charles W. Wootton. 1995. The struggle of Women in accounting: The case of Jennie Palen, Pioneer Accountant, Historian and Poet. Critical Perspectives on Accounting 6: 371–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Big 4 Accounting Firms. n.d. Available online: https://www.big4careerlab.com/big-4-accounting-firms/ (accessed on 20 January 2018).

- The Big Four Accounting Firms. n.d. Available online: https://www.wikijob.co.uk/content/financial-terms/accounting/big-four-accounting-firms (accessed on 20 January 2018).

- Treas, Judith, and Tsuio Tai. 2016. Gender inequality in housework across 20 European Nations: Lessons from Gender Stratification Theories. Sex Roles 74: 495–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ud Din, Nizam, Xinsheng Cheng, and Shama Nazneen. 2017. Women’s skills and career advancement: A review of gender (in)equality in an accounting workplace. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wermuth, L., and Monges M. 2002. Gender Stratification: A Structural Model for Examining Case Examples of Women in Less-Developed Countries, Gender stratification. Frontiers. A Journal of Women Studies 23: 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windsor, Carolyn, and Pak Auyeung. 2006. The effect of gender and dependent children on professional accountant’s career progression. Critical Perspectives on Accounting 17: 828–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).