Abstract

Social impact bonds (SIBs) have been welcomed enthusiastically as a new funding tool for social innovation, yet also condemned as an instrument that neglects beneficiaries’ and taxpayers’ interests, opening profit opportunities in the field of social politics for smart private investors. We will shed a more analytical light on SIBs, assuming that, like any contract, SIBs try to align interests between partners with partly converging, partly diverging goals. Thus, it remains mainly a matter of negation, and non-profit social service providers as well as public agencies should avoid particular perils and pitfalls.

1. Introduction

Among the novelties that have occurred in the non-profit sector in recent years, social impact bonds (SIBs) have been one of the most controversially discussed. SIBs are a new kind of funding instrument that combines characteristics of equity, debt and derivatives. Since the inception of the first SIB in 2010 in the UK, 31 more have been implemented in the UK, 14 in the USA, and a few more in various other countries (Instiglio 2017).

SIBs come in many variations (Arena et al. 2016; Clifford and Jung 2016) and are known by different names in different locations: The term “Social Impact Bond” is mostly used in the UK, “Pay for Success” is the common term in the USA, the term “Social Benefit Bond” is used in Australia. Yet all of those forms of funding share certain commonalities: they involve a contract between a commissioner, who is almost invariably a government, and a commissioning agency. The commissioning agency may be an intermediary who prepares the deal, administers it, and subcontracts with social-service-providers (SSPs). Alternatively, the commissioning agency may be a SSP acting as prime contractor and subcontracting with other SSPs, or may also act as an investor. SSPs are typically private non-profit organizations, but also social businesses or for-profit SSPs. At least one investor is involved, who is legally separate from the SSP and the commissioner. This investor may be philanthropic, profit-, or blended value-oriented. The investor may take on all or a part of the risk of non-performance, with or without guarantee of principal, with longer or shorter time to maturity. Payments are made from the commissioner to the investor, if SSPs meet predefined social outcomes. Whether those outcomes have been attained is usually assessed by an independent evaluator.

These characteristics make SIBs hybrid financial instruments par excellence: like a derivative, the value of a SIB depends on the occurrence of a particular event, specifically on the achievement of social impact. However, unlike in a derivative, the investor has to provide up-front capital that covers all or a large part of the projected costs. Like debt, the investment has a fixed term, the maximum return is capped, and the capital may be partly or fully secured. Alternatively, like equity, the capital may be fully at risk. The areas of application for SIBs centre on social problems where it is relatively feasible to identify the effects of an intervention on individuals or on a clearly delineated group, for example anti-recidivism programmes, training and counselling programmes to reduce unemployment, programmes to prevent school dropouts, etc.

Research and scholarly debate about SIBs has mainly been conceptual so far (Fraser et al. 2016). Empirical research has mostly been in the form of evaluation reports, with only a few academic studies (Arena et al. 2016; Cooper et al. 2016; Edmiston and Nicholls 2017) analysing existing SIBs with empirical methods. The conceptual arguments concerning SIBs have been following distinctive narratives (Fraser et al. 2016): A public-sector-reform narrative located within broader theories of Public Management, a private-financial-sector-reform narrative located within broader theories of social entrepreneurship, and a cautionary narrative sceptical of new public management and social entrepreneurship.

The core idea of the public-sector reform narrative is that non-profit and public-sector organizations have important shortcomings in terms of impact-orientation and accountability, which have hampered them to effectively tackle entrenched social problems. SIBs are considered as a way to remedy those shortcomings. The core message of the private-financial-sector-reform narrative is that SIBs will enable private financial investors to align the pursuit of financial benefits with the pursuit of social benefits, thus offsetting the anti-social aspects of financial capitalism. Between these two narratives there is considerable overlap, as many of their proponents see SIBs as ‘win-win-win’ options in the context of financial austerity.

The cautionary narrative is, for the most part, favourably disposed to the outcome-oriented and evidence-based approach that is central to SIBs, but highlights problematic aspects of SIBs. Some of those problematic aspects concern rather technical difficulties, such as choosing outcome indicators and calculating risks (for an overview see, for example, Roy et al. (2017)). A recent empirical study by Edmiston and Nicholls (2017) compares four SIBs in the UK to assess whether they have engendered some of the effects that have been said to be benefits of this funding instrument: innovation in service delivery, improved social outcomes, future cost savings, and additionality. They find that the evidence base to support that SIBs are superior to other forms of funding in any of these dimensions is thin, and where evidence is available, it is rather mixed or ambivalent. The political implications of SIBs have been examined critically by Sinclair et al. (2014) who analyse SIBs as fundamentally changing the status of the service user from a citizen entitled to support into a commodity processed for profit. Similarly, in an in-depth case study of the London Homelessness SIB, Cooper, Graham et al. (2016) find that the SIB undermines systemic understandings of the homelessness problem and replaces them with an understanding centred on the homeless person as a failed individual, who becomes securitized into the potential future cash flow of investors.

With this commentary we aim to contribute to the cautionary narrative from a novel perspective: When SIBs turn out as ‘win-win-win’ options for governments, investors and non-profit SSPs, what does that mean for other actors, namely beneficiaries and taxpayers? Are they bound to ‘win’ too, or may there be negative effects of aligning the interests of key actors? We shall identify two potential perils of SIBs aligning interests among key actors: displacement of non-profit SSPs’ interests to the disadvantage of their beneficiaries, and collusion of key actors in decisions on funding conditions to the disadvantage of taxpayers.

2. How SIBs Align Interests

It is a key argument in the practitioner literature (e.g., (Dear et al. 2016, p. 21; Social Finance 2012, pp. 10 ff.)) as well as in parts of research (e.g., (Goodall 2014, p. 5; Giacomantonio 2017, p. 3)) that a well-defined SIB creates an incentive structure that aligns the interests of governments, investors and SSPs around the delivery of a pre-agreed set of outcomes. Yet what exactly does alignment of interests mean, and do SIBs really do that? We shall explore those questions in the following sections.

2.1. What Does ‘Alignment of Interests’ Mean?

The concept of interests is at the core of agency theory, which is fundamental to the notion of SIBs. Agency theory has traditionally been employed to explain and shape contractual relations between public agencies and private SSPs (e.g., (Coats 2002)). What it means for an actor to have a particular interest is hardly specified in agency theory, as interests correspond to the actors’ utility function, which may take on any form, representing any kind of preferences. A look at the historical roots of economic theory illuminates more: The concept of interests refers to aspirations—be they material or non-material—that are pursued in a manner that includes an element of reflection and calculation (Hirschman 1997, p. 32).

Alignment of interests is one of the two major ways in which agency theory envisages the minimization of agency risk (Demougin and Fluet 2001): Principals can directly monitor the behaviour of agents to ensure contract compliance, and they can install incentive systems for agents that make rewards dependent on achieving particular outcomes, so that the interests of principals and agents become more aligned. What originally was the interest of the principal now becomes a strong interest of the agent, too.

Such alignment of interests also occurs if the relationship between principal and agent takes the form of a multi-round game, and the agent has an interest to continue playing the game. This has been conceptualized as ‘encapsulated interest’ (Hardin 2003): The agent counts the principal’s interests as his own interests, because he wants to maintain his relationship with the principal.

2.2. Do SIBs Align Interests?

The next question is whether SIBs actually lead to an alignment of interests, and if so, how and for which actors? The whole idea of SIBs is geared towards the alignment of interests. By making payment to the investor dependent on the achievement of outcomes, and by imposing rigorous outcome evaluations, they turn what otherwise would have been a game based on incomplete information into a multi-round game based on more complete information.

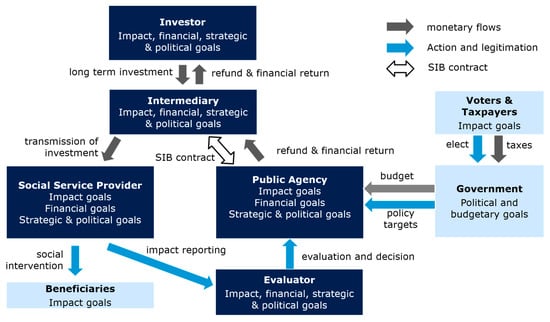

When analyzing the SIB framework in more detail, however, the constellation of interests turns out to be far more complicated. Like any contract, a SIB can only induce a partial alignment of the key actors’ interests. Even if interest alignment in a SIB is substantially stronger than with other forms of contracting, due to their outcome-based incentives, each actor continues to have also interests of their own that diverge from or even conflict with those of the others (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Actors, transactions, and interests in a social impact bond (SIB) constellation.

The formal SIB contract aligns only selective interests of the five key actors: investor, intermediary, social-service-provider, evaluator and public agency. Only two or three of them (the public agency, the intermediary, and often the investor) usually participate in negotiations of the original SIB contract, thus actively placing their stakes into this contract.

The government will typically be concerned with imperatives of the political system, such as being re-elected, effectively dealing with coalition partners, satisfying budgetary rules or portfolio requirements imposed by higher levels of government or the law (e.g., the Community Reinvestment Act in the USA), etc. Usually, government itself is represented by a specific agency with expertise in fields of social policy or social work. Those agencies develop their own impact goals and political goals, which specify the government’s overall policies.

Government ideally acts as steward of fundamental human rights for all people, and in particular for the interests of the electorate (Donaldson and Davis 1991). Governments and public agencies are only loosely coupled with the electorate’s preferences. This is particularly acute in the case of SIBs: Very few voters even know what a SIB is. Even fewer voters will be informed about the details of a particular SIB contract. Specific information about SIBs, for example about their transaction costs, is never made public though it might be of interest for taxpayers.

The public agency that contracts the SIB usually pursues not only the overall governmental policy goals but specifies them for its policy field. Its major interest to engage in a SIB is to fund (risky) interventions that cannot be covered by regular budgets. Still, it has to act within budgetary constraints, which very often restrict the potential volume of SIBs. In addition, it may pursue idiosyncratic strategic goals such as to strengthen its reputation as an innovative public actor.

Theoretically, SIBs should attract mainly impact investors. Traditional financial investors would seek a financial return similar to market-based risk-return-ratios. Impact investors will be satisfied with a lower financial return, but most commonly they will at least expect a return slightly beyond the bond market. Moreover, impact investors will usually have a strong interest in promoting certain kinds of social policy.

It has often been argued that the ‘evidence-based’ approach of SIBs would settle disagreements about social policy issues pragmatically by means of impact-measures. However, any research based on, for example, Foucauldian theory (e.g., (Cooper et al. 2016)) or institutional theory (e.g., (Smith 2013)) shows that evidence-based policy is not such a straightforward matter. Facts do not speak for themselves. Like all public policy instruments, also SIBs ultimately rest on some normative understanding of the common good (Roy et al. 2017). The power of facts is highly dependent on context, and research evidence remains but one kind of power to mobilize in support for certain social policies. An agreement on measures necessarily means a compromise on impact goals.

It is inherent to the way SIBs work that they fund social policy measures that aim to prevent or ameliorate social problems by making interventions at the level of individuals or their immediate surroundings. For example, in the Essex SIB parents of troubled young people are given education advice; the Freso SIB aims to help children with asthma by teaching parents how to remove mold. SIBs are not instruments to tackle systemic causes of such problems, such as pervasive gender norms that are conducive to violence among male teens, or air pollution that causes asthma, to give two arbitrary examples. Within their larger political context, SIBs are often concomitant to prioritizing individual-level measures over systemic ones (see (Cooper et al. 2016)). Even the SIB missing its impact targets may be in the interest of governments’ and public agencies, if they do not calculate with a multi-round game and thus receive at least some social impact at very low cost.

For SSPs, SIBs can be attractive because they provide stable funding. Moreover, many SIBs define specific outcome metrics but hardly prescribe a specific intervention model (although, it should be noted, some SIBs precisely define intervention as well as outcome). Purely outcome-oriented SIBs give SSPs more freedom to innovate and personalize services according to client needs than most other kinds of government funding (Fraser et al. 2016, p. 7). However, in the course of a SIB, the interests of SSPs may nonetheless partly diverge from the other parties: Non-profit SSPs in particular should, ideally speaking, act as a steward for the interests of their beneficiaries. In most cases, however, this stewardship is grounded in the SSPs expertise, and not in participation of beneficiaries in the governance of SIBs. It may then turn out that what all partners had originally believed to be in the beneficiaries’ best interest actually creates considerable tensions. For example, when it is agreed as an outcome that a certain number of individuals should achieve a certain goal (e.g., enter employment or abstain from criminal offences), this creates an incentive to focus on those individuals who have relatively good chances to reach the goal, rather than to work with more difficult clients (cream skimming). In any case, the SSP is interested in designing eligibility criteria, enrolment targets, outcome metrics, success thresholds and evaluation methods in such a way that the SIB has a high likelihood of meeting the outcome targets. In this regard, the interests of the SSP and the financial investor widely overlap, because the investor bears the financial risk, and the SSP bears reputational risk. Those interests may be in tension with those of the government agency, which may have alternative options for funding and operating the programme.

In addition to governments, public agencies, investors and SSPs, SIBs also introduce two new types of actors in distinctive roles: intermediaries and evaluators. Those actors usually receive a fixed payment. They are not just impartial brokers and assessors of the SIB; they are also interested in making the SIB as such into a success, to keep them in business in this emerging field. Intermediaries have invested much pro bono work into SIB pilots in various countries and new areas of application, in the hope that SIBs will become established finance instruments in the long run (e.g., (KPMG 2014)).

To sum up, SIBs align interests by incentivizing the attainment of fixed outcome measures more strongly than other forms of contracting such as block contracts or spot contracts. However, all actors also maintain a set of preferences and interests of their own. In the following section, we shall proceed to examine potential downsides of the relatively strong alignment of interests by means of SIBs.

3. The Perils of Aligned Incentives

Aligning interests in a new way means partially displacing or at least modifying previous interests. Given that non-profit SSPs as well as governments are also stewards of beneficiaries, respectively taxpayers, such displacement of interests may not always go together well with their fiduciary responsibilities. Specifically, we have observed two variants in how SIBs may lead to a perilous alignment of interests among key actors: Firstly, the choice of inadequate outcome measures may create perverse incentives that displace the previous interests of non-profit SSPs to the detriment of some of their beneficiaries. Secondly, all of the key actors involved in a SIB may lapse into an infatuation with the SIB instrument as such, resulting in funding terms that are suboptimal from a taxpayer’s perspective.

3.1. Misleading Incentives: Displacement of Non-Profit SSPs’ Interests to Beneficiaries’ Detriment

Much has already been written about issues to consider when developing outcome indicators and success thresholds for SIBs (e.g., (Rohacek and Isaacs 2016)). Most of this concerns issues where governments, investors and SSPs could reasonably be expected to all have the beneficiary’s best interests at heart. However, a rather thorny issue concerns the choice between binary outcome metrics and frequency outcome metrics. A binary outcome metric is one that classifies a beneficiary as meeting a certain criterion or not. For example, whether or not an adolescent has been assigned to institutional care, or whether or not a former inmate has reoffended, are binary outcome metrics. A frequency outcome metric counts how often a desired action has taken place or—more often, but also more difficult to operationalize—how often an undesirable action has not taken place, as opposed to what would have happened without the intervention. For example, the reduction of days in institutional care, or the reduction in re-offenses, as opposed to a historical baseline or a control group are frequency outcome metrics.

Frequency outcome metrics correspond well to the professional ethos of social workers, medical personnel, and other professionals who have been trained to work with even the most difficult clients or patients. In fact, being willing and able to take on the most difficult clients or patients is considered a sign of competence in many professions. Binary outcome metrics, in contrast, encourage SSPs to cream-skim those beneficiaries who have the highest chances of meeting the target, and to park those beneficiaries who have already missed the target or have a low probability of staying on track (McHugh et al. 2013, p. 7): Whereas their professional ethos and their stewardship for disadvantaged groups would motivate SSPs to focus on the most difficult cases, SIB metrics can motivate them to focus on the easiest.

In some SIBs, the contractual partners have been able to find frequency outcome metrics that appear to be highly adequate for the purpose at hand (e.g., various SIBs about juvenile delinquency measuring the number of re-offenses, SIBs for adolescents at the edge of care measuring avoided days in institutional care). However, it is in many cases excruciatingly difficult to find a frequency metric that is valid and can be measured at a reasonable cost, especially if it should measure the frequency of something not happening. Many SIBs therefore use binary metrics. In those cases, it is almost impossible to avoid exposing SSPs to some kind of perverse incentives. To ameliorate this problem, many SIBs have averted to using several counterbalancing binary metrics, instead of one. For example, the SIB may incentivize some upstream outcomes (e.g., young person at risk of unemployment completing education) and some downstream outcomes (e.g., a young person entering employment). Such combinations of metrics, however, create problems of their own, as SSPs become incentivized to prioritize the easier to achieve outcomes over the more difficult ones.

3.2. ‘SIB Fever’: Agreement on Funding Conditions to Taxpayer’s Detriment

In times of austerity and budget cuts, and driven by the norms of new public management, governments and public agencies may develop a preference for the SIB approach as such. This may lead to an uncontrolled favouring of SIBs on the side of all involved key players. Under such a condition of ‘SIB fever’, SIBs can become a funding form that is more expensive than conventional ways of financing social policies through taxes or government debt.

Virtually all institutions involved in the creation and management of SIBs emphasize that SIBs are a way of making more efficient and effective use of taxpayer’s money (Maier et al. 2016). It is argued that by aligning the interests of key actors around the achievement of specific outcomes, and by getting investors from the private sector involved, SIBs would instill market discipline into the social sector and would relieve the public purse from having to pay for unsuccessful projects. It is rarely thematised, however, that such risk transfer comes at a cost. If financial investors are involved, they will require a risk-return-rate at market level. Impact investors will accept below-market-rate returns, but still the transaction costs for the SIB need to be borne by somebody. Evaluations suggest that transaction costs for pilot SIBs have been higher than those of other funding instruments (e.g., (Disley et al. 2011, p. 15; Tan et al. 2015, p. 5; KPMG 2014, p. 20)). In those cases, SSPs, intermediaries and public agencies have invested enormous amounts of time and effort to get SIBs running. It seems that UK government institutions have been able to bring those transaction costs down by using somewhat standardized methods for tendering several SIBs at once (Ronicle et al. 2016, pp. 20, 35). However, transaction costs will have to come down further if SIBs are to become truly competitive with more established finance instruments in terms of their costs (also see (Gustafsson-Wright et al. 2015, p. 35)).

For SIBs’ cost-efficiency, it is paramount that the government maintains a neutral stance towards all kinds of funding instruments and chooses between them strictly on the basis of their financial interest, risk-taking-propensity, transaction costs, and contribution to desired outcomes for beneficiaries. This is important because, between investors and SSPs, there will be an overlap of interests: SSPs will have an interest to set success criteria in a way that they will likely attain them, in order to maintain their reputation and further funding. Investors will also have an interest to set success criteria at an attainable level, and at conditions that are financially attractive. To counterbalance those interests, government must pressure for success thresholds that are ambitious and for repayment conditions that are at least equivalent to funding alternatives. Ideally, given that all key actors have an interest to maintain co-operation and to enable the closure of further SIB contracts, this should result in a risk-return-rate at market level, or in the case of impact investors, below market.

This mechanism becomes tilted if governments have strategic and political interests in SIBs per se. The most important reason in this regard is probably the bipartisan appeal of SIBs: SIBs are basically supportive of governmental welfare-spending, but combine this with a risk-shift to private investors and a promise of market-like incentives. They may thus garner much broader support than other forms of financing social welfare. Governments and public agencies engage in SIBs also for reasons of mimetic isomorphism (DiMaggio and Powell 1983), imitating the actions of other governments that they regard highly. If such factors work, all key actors will have an interest in setting success thresholds too low and agreeing on excessively generous terms. SIBs would then turn into a funding tool that harms the interest of taxpayers.

A prominent example that appears to fit the description of ‘SIB fever’ is the case of the Utah School Readiness Initiative: The state of Utah and United Way have closed a contract for 7 million USD with Goldman Sachs and philanthropic investors, as well as various non-profit SSPs, to provide a preschool curriculum for underprivileged children. This curriculum is meant to improve their school readiness, and to save cost for special education those children otherwise would need in grade school (for more detailed information see (Stump and Johnson 2016, p. 12; Golden et al. 2016, pp. 13 ff.)). Previous attempts to provide free preschool education to children in need had faltered in Utah due to insufficient political will to provide the necessary funding. With the possibility to fund this measure through a SIB, political will shifted (Gustafsson-Wright and Gardiner 2016, p. 27). It was agreed that all participating children would be administered a standardized test. Those who scored below average were predicted to need special education services in grade school. If in grade school those children were assessed to not need special education, this was considered a success of the programme. If at least 50% of the children predicted to need special education turned out not to need it, Goldman Sachs would be paid its money back and receive a 5 per cent interest (Popper 2015). When the first results were released in October 2015, it turned out that 109 of the 110 students who had been defined at risk according to the test did not require special education. A public debate among education experts ensued. Many experts pointed out that the test that had been used was inappropriate for assessing the likelihood of special education needs among the tested group of children. Moreover, a success rate of over 99%, such as in this programme, was completely unheard of in hundreds of studies that evaluated similar programmes. It was criticized that the threshold for the outcome payments had been set far too low; ‘these kids weren’t in line for special education in the first place’ (Popper 2015).

4. Conclusions: It’s Negotiation, Stupid

SIBs per se are neither the silver bullet for funding social policy nor the neo-liberal devil’s handiwork. In this commentary, we have focused on perils of the instrument, because benefits have been sufficiently argued by its proponents. SIBs can be appropriate instruments to fund social innovations and strengthen the entrepreneurial state (Mazzucato 2015) with the help of private impact investors, or—as indicated in the Utah case—they can accommodate public agencies that have become highly risk-adverse even in their core fields of social policy. The latter happens when SIBs are used to fund social interventions for which the benefits are already supported by sound empirical evidence, and which do not tackle high-risk beneficiaries (such as juvenile delinquents). In that case, SIBs may have the adverse effect of actually making social innovations harder to scale, if there is no private risk-sharing available.

As almost any contract, SIBs involve actors with complex, partly converging and partly diverging interests. Proponents should avoid the illusion that all these interests can be easily aligned without displacing or neglecting some of them. It is impossible to merge these interests into a complete contract that fully satisfies all. At best, partners can agree on a psychological contract (Rousseau 1995) that hinders actors to pursue a hidden agenda at the cost of others. Moreover, in the best of all SIB-worlds, actors engage in honest and thorough negotiations to align their interests as far as possible. In doing so, public agencies and non-profit SSPs must take particular care to avoid mission drift and to maintain their stewardship functions for their beneficiaries or voters. All actors should be aware of alternatives, and public agencies and governments in particular should carefully balance pros and cons, and should have sufficient expertise both in financial markets and social policy to avoid striking a poor deal (as it seems to have happened in the Utah case).

In this commentary, we have concentrated on spelling out contractual issues and the alignment of interests in rather descriptive terms. Further research would be needed to identify which factors are conducive to the negotiation of SIB contracts that safeguard beneficiaries’ and taxpayers’ interests. We would assume that the presence of competent actors who participate in public debate about SIBs without having a vested interest in favor of the instrument would be beneficial. In recent years, we have for example seen journalists (Popper 2015), researchers at universities (e.g., (Roy et al. 2017)), research institutes (e.g., (Loxley and Puzyreva 2015)), think tanks (Whitfield 2015), and unions of public sector employees (e.g., (Malcolmson 2014)) take on this role with varying intensity in various countries. It may also make sense to experiment with SIBs that include a formal element for involving constituents (beneficiaries, taxpayers, voters) in the governance system of the SIB. There are no simple recommendations how to do this, yet considering those interests more formally could enhance the democratic legitimation of SIBs and avoid giving the impression of a secret agreement between private investors and public agencies.

Latest figures show that SIBs’ rate of adoption has been relatively modest in recent years and the diffusion curve is not ramping-up (Arena et al. 2016, p. 928), even when taking into account that SIB-like performance contracts may carry a variety of names. A worldwide epidemic of ‘SIB fever’ therefore may fail to occur. Despite some negative examples such as the Utah case, it seems that, by and large, SSPs and governments have been doing a good job deciding about SIBs on the basis of beneficiaries’ and taxpayers’ best interests. We therefore would not mind if with this cautionary commentary we have been preaching to the choir, and we remain optimistic about the possibility to use SIBs as adequate instruments in specific niches of social welfare provision: when innovative programs are delivered to high-risk populations with the support of social impact investors who accept returns slightly below market rates. At the same time, we expect that key elements of the SIB idea, such as impact-oriented funding and the involvement of private investors, will stay high on the agenda. Many of the points that we have highlighted in this commentary will be relevant also for other kinds of impact-oriented public–private partnerships.

Author Contribution

Both co-authors developed the conceptual ideas for this paper together and jointly put them into writing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Arena, Marika, Irene Bengo, Mario Calderini, and Veronica Chiodo. 2016. Social Impact Bonds: Blockbuster or Flash in a Pan? International Journal of Public Administration 39: 927–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifford, Jim, and Tobias Jung. 2016. Social Impact Bonds: Exploring and Understanding an Emerging Funding Approach. In The Routledge Handbook of Social and Sustainable Finance. Edited by Othmar Lehner. London: Routledge, pp. 161–76. [Google Scholar]

- Coats, Jennifer C. 2002. Applications of Principal-Agent Models to Government Contracting and Accountability Decision Making. International Journal of Public Administration 25: 441–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, Christine, Cameron Graham, and Darlene Himick. 2016. Social impact bonds: The securitization of the homeless. Accounting, Organizations and Society 55: 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dear, Annie, Alisa Helbitz, Rashmi Khare, Ruth Lotan, Jane Newman, Gretchen Crosby Sims, and Alexandra Zaroulis. 2016. Social Impact Bonds: The Early Years. London: Social Finance. [Google Scholar]

- Demougin, Dominique, and Claude Fluet. 2001. Monitoring versus incentives. European Economic Review 45: 1741–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, Paul J., and Walter W. Powell. 1983. The iron cage revisited: Collective rationality and institutional isomorphism in organizational fields. American Sociological Review 48: 147–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Disley, Emma, Jennifer Rubin, Emily Scraggs, Nina Burrowes, Deirdre M. Culley, and RAND Europe. 2011. Lessons Learned from the Planning and Early Implementation of the Social Impact Bond at HMP Peterborough; London: Ministry of Justice.

- Donaldson, Lex, and James H. Davis. 1991. Stewardship Theory or Agency Theory: CEO Governance and Shareholder Returns. Australian Journal of Management 16: 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmiston, Daniel, and Alex Nicholls. 2017. Social Impact Bonds: The Role of Private Capital in Outcome-Based Commissioning. Journal of Social Policy, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, Alec, Stefanie Tan, Mylene Lagarde, and Nicholas Mays. 2016. Narratives of Promise, Narratives of Caution: A Review of the Literature on Social Impact Bonds. Social Policy & Administration. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacomantonio, Chris. 2017. Grant-Maximizing but not Money-Making: A Simple Decision-Tree Analysis for Social Impact Bonds. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodall, Emilie. 2014. Choosing Social Impact Bonds: A Practitioner’s Guide. London: Bridges Ventures. [Google Scholar]

- Golden, Megan, Brian Nagendra, and Kevin Seok-Hyun Mun. 2016. Pay for Success in the US: Summaries of Financed Projects. Greenville: Institute for Child Success. [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson-Wright, Emily, and Sophie Gardiner. 2016. Using Impact Bonds to Achieve Early Childhood Development Outcomes in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Washington: Brookings Institution. [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson-Wright, Emily, Sophie Gardiner, and Vidya Putcha. 2015. The Potential and Limitations of Impact Bonds: Lessons from the First Five Years of Experience Worldwide. Washington: Brookings Institution. [Google Scholar]

- Hardin, Russell. 2003. Gaming trust. In Trust and Reciprocity: Interdisciplinary Lessons from Experimental Research. Edited by Elinor Ostrom and James Walker. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, pp. 80–101. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschman, Albert O. 1997. The Passions and the Interests: Political Arguments for Capitalism before Its Triumph. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Instiglio. 2017. Impact Bonds Worldwide. Available online: http://www.instiglio.org/en/sibs-worldwide/ (accessed on 2 April 2017).

- KPMG. 2014. Evaluation of the Joint Development Phase of the NSW Social Benefit Bonds Trial. Sidney: KPMG. [Google Scholar]

- Loxley, John, and Marina Puzyreva. 2015. Social Impact Bonds: An Update. Winnipeg: Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. [Google Scholar]

- Maier, Florentine, Gian Paolo Barbetta, and Franka Godina. Paradoxes of Social Impact Bonds. Paper presented at the ISTR conference, Stockholm, Sweden, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Malcolmson, John D. 2014. Social Impact Bonds: Cleared for Landing in British Columbia. Burnaby: Canadian Union of Public Employees. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzucato, Mariana. 2015. The Entrepreneurial State: Debunking Public vs. Private Sector Myths. New York: PublicAffairs. [Google Scholar]

- McHugh, Neil, Stephen Sinclair, Michael J. Roy, Cam Donaldson, and Leslie Huckfield. 2013. Social impact bonds: A Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing? Journal of Poverty and Docial Justice 21: 247–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popper, Nathalie. 2015. Did Goldman Make the Grade? The New York Times, November 4. [Google Scholar]

- Rohacek, Monica, and Julia Isaacs. 2016. PFS + ECE: Outcomes Measurement and Pricing: Pay for Success Early Childhood Education Toolkit Report #3. Washington: Urban Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Ronicle, James, Tim Fox, and Neil Stanworth. 2016. Commissioning Better Outcomes Fund Evaluation: Update Report. N.d.: Big Lottery Fund, ATQ Consultants, Ecorys. [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau, Denise M. 1995. Psychological Contracts in Organizations: Understanding Written and Unwritten Agreements. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, Michael J., Neil McHugh, and Stephen Sinclair. 2017. Social Impact Bonds: Evidence-based Policy or Ideology? In Handbook of Social Policy Evaluation. Edited by Bent Greve. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 263–78. [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair, Stephen, Neil McHugh, Leslie Huckfield, Michael J. Roy, and Cam Donaldson. 2014. Social Impact Bonds: Shifting the Boundaries of Citizenship. In Social Policy Review 26: Analysis and Debate in Social Policy. Edited by Kevin Farnsworth, Zoë Irving and Menno Fenger. Bristol: Policy Press, pp. 119–13. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Katherine. 2013. Beyond Evidence Based Policy in Public Health: The Interplay of Ideas. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- A New Tool for Scaling Social Impact: How Social Impact Bonds Can Mobilize Private Capital for the Common Good. 2012. Boston: Social Finance.

- Stump, Erika, and Amy F. Johnson. 2016. An Examination of Using Social Impact Bonds to Fund Education in Maine. Portland: University of Southern Maine. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Stefanie, Alec Fraser, Chris Giacomantonio, Kristy Kruithof, Megan Sim, Mylene Lagarde, Emma Disley Jennifer Rubin, and Nicholas Mays. 2015. An Evaluation of Social Impact Bonds in Health and Social Care: Interim Report. London: PIRU. [Google Scholar]

- Whitfield, Dexter. 2015. Alternative to Private Finance of the Welfare State: A Global Analysis of Social Impact Bond, Pay-for-Success & Development Impact Bond Projects. Adelaide: University of Adelaine, Australian Workplace Innovation and Social Research Centre and European Services Strategy Unit. [Google Scholar]

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).