University Knowledge Transfer Offices and Social Responsibility

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theory and Practice of Knowledge Transfer Office

2.1. Mission of University Knowledge Transfer office (UKTO)

- Commercialization of licensing agreements;

- Collaborative research partnership, research services, and consultancy; and

- University-based start-ups or academic entrepreneurship.

- (1)

- Set up and Managing Research Project: This relates to the identification of the type of research projects, the collation of costs (and therefore establishing a price), the control of the key phases of negotiation, the authorization of, and follow-up on, progress of each contract.

- (2)

- Patent and Entrepreneurship: It is the ability for a UKTO to enable the transfer of intellectual property (IP) from public research teams to private firms and to facilitate entrepreneurial activity. This relates to the usual activities surrounding the protection of IP, the process of patenting, the establishment of technology offers, and licensing.

- (3)

- Knowledge Sharing and Support Services to Enterprises: This competence is the ability to promote and develop knowledge-based support services for enterprise, and share best-practices between public and private research partners. For instance, the “sharing of facilities” can help a firm to build prototypes or access equipment. To compliment this, training or the provision of continuing professional development for companies can be developed by UKTOs.

- (4)

- Boundary Spanning through human resources: The fourth competence relates to the capability of establishing knowledge-based boundary-spanning activities through the effective mobilization of people (human resources). This relates to an ability to create knowledge through externalization and socialization, as promoted by Nonaka [30]. A key concept in this is the “network as knowledge” [31]. This could be realized by the organization of joint conferences, for example.

- (1)

- Research projects lead to an invention.

- (2)

- Invention of a technical concept that is protected, perhaps by a patent. Both research projects and invention of a technical concept, may be publicly funded. The technical entrepreneurs who created the concept in phase two, may have little business experience, but they have a high commitment to their technical vision. Troy and Werle [33] explain the patent markets and suggest that the emergence of a well-functioning market for patented new technological knowledge is confronted with several obstacles, which can be characterized as different facets of uncertainty. They are included in the process of creation of innovative knowledge, in its transformation into a fictitious knowledge commodity (patent), in its uniqueness, in the strategy of transaction partners, in the estimation of the future market potential of final products (based on the patents), and generally in the problem of incomplete and asymmetric information. In addition, a commonly accepted model of determining a patent’s value is missing.

- (3)

- Early Stage Technology Development of Innovation (ESTDI). This is the most critical phase in the transition from invention to innovation, the technology is reduced to industrial practice, a production process is defined from which costs can be estimated, and a market appropriate to the demonstrated performance specifications is identified and quantified. Not only business angels and technology labs help with the funding in this phase, but also the “3Fs”: fools, friends and family. This space can be understood as a sea of life and death of business and technical ideas, of “big fish” and “little fish” contending, with survival going to the creative, the agile, the persistent. Thus, Aueswarld and Branscomb [32] propose an alternative image than the “Valley of Death” used by congressmen in USA: the “Darwinian Sea”.

- (4)

- Product Development (PD). A pilot line is produced and the enterprise is ready to enter the market. At this point, an innovation is achieved. Business Angels and Venture Capitalists introduce financial funds in this phase.

- (5)

- Production and Marketing. The product goes to the market, and the business is viable. The venture capital industry, always looking for opportunities to invest where the returns may be high enough to justify the business risks, are unlikely to take the opportunity seriously until Phase 5. In some cases, they will invest, in an exploratory way, during Phases 3 and 4.

- (6)

- Setting up global activities while still being in the start-phase remains a very complex task. After all, global start-ups do not only have to deal with the usual problems associated with the launching of a new venture, such as accumulating resources, building reputation, finding partners and attracting customers. The main current needs of global academic start-ups and the support offered by universities to fulfill them are related to the lack of commitment towards internationalization, lack of managerial international skills and lack of resources for the internationalization [34]. In this sense, universities can play and important role helping academic entrepreneurs to overcome these needs, as well as creating an international entrepreneurial culture for the development of potential global start-ups in the academic environment.

2.2. UKTO and Inter-Organizational Collaborations among Stakeholders. An Institutional Perspective

- (1)

- Interactions: The pattern of interactions among collaborating organizations.

- (2)

- Structures and holes: The structure of coalition formed by collaborating partners and brokers that span boundaries.

- (3)

- Information flow: The pattern of information sharing among collaborating partners through procedures and routines.

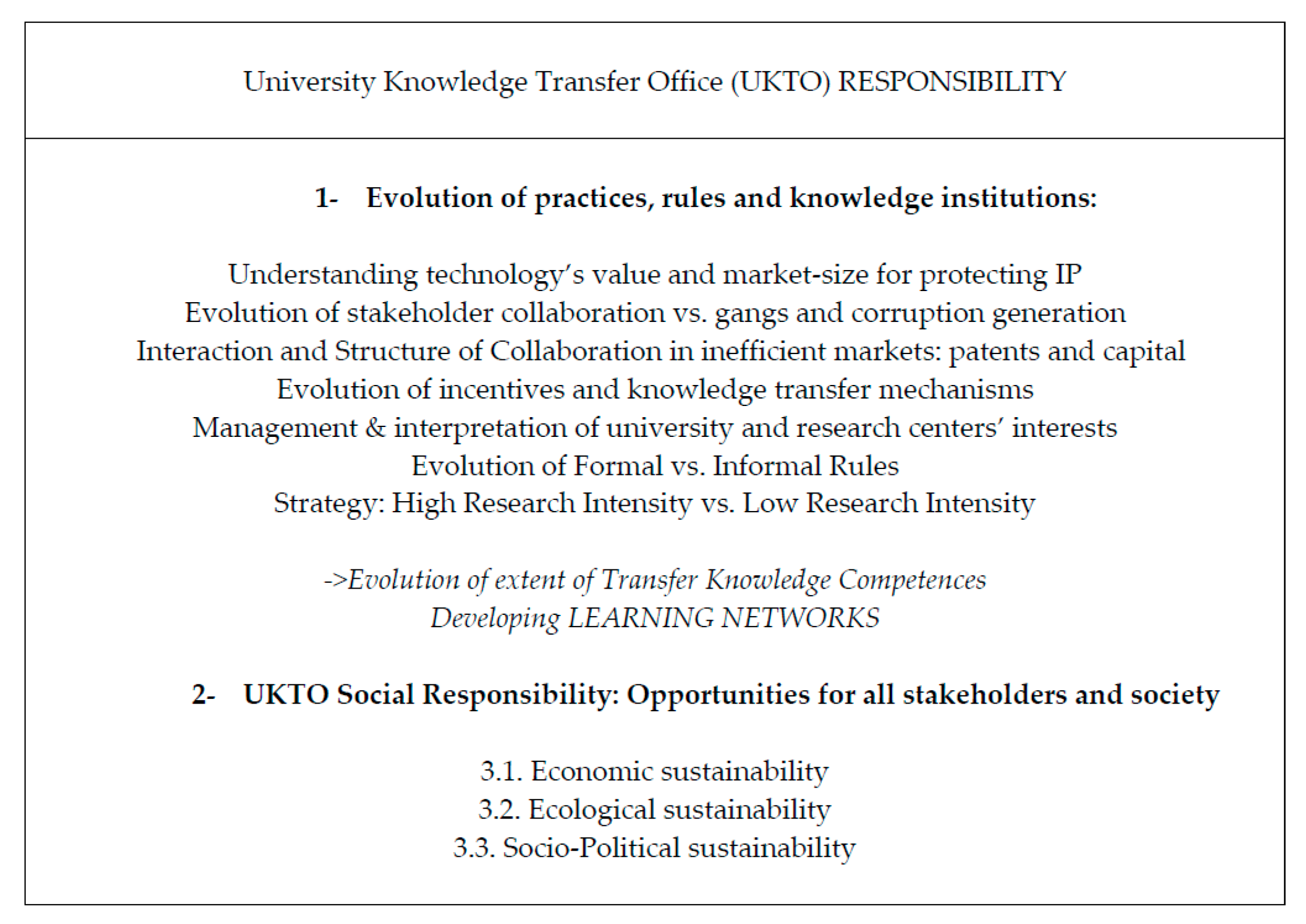

3. Institutional Effects and Social Responsibility

- (1)

- An important dimension is the “level of knowledge transformation” that takes place in the transfer and the relational intensity (i.e., the extent of direct personal involvement). Knowledge is not just information, but also incorporates more intangible aspects (tacit “know how”). Knowledge Transfer (KT) channels involve some degree of interaction with the knowledge creator to allow the transfer to be successfully realized.

- (2)

- Another dimension is the “significance to industry”. Surveys of industry representatives yield similar and robust overall rankings channels; scientific publications and collaborative research are some the highly KT channels for industry, while commercialization of property rights and exchange of personnel are rated below.

- (3)

- “Knowledge finalization” and the “degree of channel formalization” are additional dimensions. Knowledge finalization refers to the degree to which a project can be contained in discrete deliverables or is more open-ended, and it approximates the type of knowledge involved in KT. The appropriateness and complexity of knowledge will influence the type of KT channel that is used. Chanel formalization refers to the extent to which the interaction is institutionalized and/or guided by formal rules and procedures.

UKTO’ Social Responsibility

- (1)

- Some universities could follow a fairly narrow strategy focusing on world-class innovations, or High Research Intensity (HRI) Strategy.

- (2)

- While others, perhaps the majority, should pursue a more modest approach developing broader innovations that are more appropriate in a regional and local context. These universities can exploit the patent of the most innovative to develop new spin-offs on their context. The mission shift toward evaluating the commercial feasibility of all new inventions in their region. This is called Low Research Intensity (LRI) Strategy.

- -

- Ecological sustainability: Conservation of the natural capital of nature supplemented by environmental and territorial sustainability, the former related to the resilience of natural ecosystems used as sinks, the latter evaluating the spatial distribution of human activities and rural-urban configurations.

- -

- Economic sustainability: Taken broadly, the efficiency of economic systems (institutions, policies, and rules of functioning) to ensure continuous socially equitable, quantitative, and qualitative progress. This dimension ensures that an economic system is able to produce goods and services on a continuing basis. It also maintains manageable levels of government and external debt, and avoids sectorial imbalances that damage agricultural or industrial production.

- -

- Social, political and cultural sustainability: The social dimension in Harris and Goodwin [63] is echoed in the term of human development, defined as progress toward enabling all human beings to satisfy their essential needs, to achieve a reasonable level of comfort; to live lives of meaning and interest; and to share fairly in opportunities for health and education. Political sustainability provides a satisfying overall framework for national and international governance.

4. Conclusions and Discussion

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alexander, A.T.; Martin, D.P. Intermediaries for open innovation: A competence-based comparison of knowledge transfer offices practices. Technol. For. Soc. Chang. 2013, 80, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Tong, L.; Takeuchi, R.; George, G. From the Editors-Corporate Social Responsibility: An overview and new research directions. Acad. Manag. J. 2016, 59, 534–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berbegal-Mirabent, E.; Lafuente, E.; Solé, F. The pursuit of knowledge transfer activities: An efficiency analysis of Spanish universities. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 2051–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansfield, E. Academic research and industrial innovation: An update of empirical findings. Res. Policy 1998, 26, 773–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Kane, C.; Mangematin, V.; Geoghegabm, W.; Fitzgerald, C. University technology transfer offices: The search for identity to build legitimacy. Res. Policy 2015, 44, 421–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkmann, M.; Walsh, K. University-industry relationships and open innovation: Towards a research agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2007, 9, 259–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weckowska, D.M. Learning in university technology transfer office: Transaction-focused and relations-focused approaches to commercialization of academic research. Technovation 2015, 41, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arundel, A.; Es-Sadki, N.; Perrett, P.; Samuel, O.; Lilischkis, S. Knowledge Transfer Study 2010–2012; Final Report; Deliverable 5 related to Service Contract No. RTD/Dir C/C2/2010/SI.569045; Directorate-General for Research and Innovation, Innovation Union, European Commission: Luxembourg, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ceulemans, K.; Molderez, I.; Van Liedekerke, L. Sustainability reporting in higher education: A comprehensive review of the recent literature and paths for further research. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 106, 127–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, K.; Palazzo, G. Corporate Social Responsibility: A Process Model of Sensemaking. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2008, 33, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.L. Institutional analysis and the paradox of corporate social responsibility. Am. Behav. Sci. 2006, 40, 925–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, A.; Macdonald, A.; Dandy, E.; Valenti, P. The state of sustainability reporting at Canadian universities. Int. J. Sustain. High Educ. 2011, 12, 22–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, D.S.; Waldman, D.A.; Atwater, L.E.; Link, A.N. Toward a model of the effective transfer of scientific knowledge from academicians to practitioners: Qualitative evidence from the commercialization of university technologies. J. Eng. Technol. Manag. 2004, 21, 115–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruneel, J.; D’Este, P.; Salter, A. Investigating the factors that diminish the barriers to university-industry collaboration. Res. Policy 2010, 39, 858–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkmann, M.; Tartar, V.; McKelvey, M.; Autio, E.; Broström, A.; D’Este, P.; Fini, R.; Geuna, A.; Grimaldi, R.; Hughes, A.; et al. Academic engagement and commercialization: A review of the literature on university-industry relations. Res. Policy 2013, 42, 423–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkman, M.; Salter, A. How to create productive productive partnership with universities. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2012, 53, 79–98. [Google Scholar]

- Markman, G.D.; Siegel, D.S.; Wright, M. Research and technology commercialization. J. Manag. Stud. 2008, 45, 1401–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leisching, A.; Geigenmueller, A.; Lohman, S. On the role of alliance management capability, organizational compatibility, and interaction quality in interorganizational technology transfer. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 1049–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, T.B.; Hardy, C.; Phillips, N. Institutional Effects of inter-organizational collaboration: The emergence of proto-institutions. Acad. Manag. J. 2002, 45, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattit, J.M.; Raj, S.P.; Wilemon, D. An institutional theory investigation of U.S. technology development trends since the mid-19th century. Res. Policy 2012, 41, 306–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, L.; Waguespack, D.M. Brokerage, Boundary Spanning, and Leadership in Open Innovation Communities. Org. Sci. 2007, 18, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, R.S. Structural Holes; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Burt, R.S. The Socio Capital of Structural Holes. In New Directions in Economic Sociology; Guillén, M.F., Collins, R., England, P., Meyer, M., Eds.; Russel Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 202–247. [Google Scholar]

- Majidpour, M. International technology transfer and the dynamics of complementarity: A new approach. Technol. For. Soc. Chang. 2016, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Gallagher, K.S. Innovation and technology transfer through global value chains: Evidence from China’s PV industry. Energy Policy 2016, 94, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, M.L.; Jennings, J.E.; Jennings, P.D. Do the stories they tell get them the money they need? The role of entrepreneurial narratives in resource acquisition. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 1107–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H. The Path to Open Innovation; Harvard Business Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Siegel, D.; Waldman, D.A.; Link, A. Assessing the impact of organizational practices on the productivity of university technology transfer offices: An explanatory study. Res. Policy 2003, 32, 27–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponomariov, B.; Boardman, C. Organizational Behavior and Human Resource Management for Public to Private Knowledge Transfer. An analytic review of the literature. OECD Sci. Technol. Ind. Work. Paper 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonaka, I. A dynamic theory of organizational knowledge creation. Org. Sci. 1994, 5, 14–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogut, B. The network as knowledge: Generative rules and the emergence of structure. Strategy Manag. J. 2000, 21, 405–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auerswald, P.E.; Branscomb, L.M. Valleys of Death and Darwinian Seas: Financing the Invention to Innovation Transition in the United States. J. Technol. Transf. 2003, 28, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troy, I.; Werle, R. Uncertainty and the Market for Patents. 2008. Available online: https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/41680/1/574282009.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2016).

- Wakkee, I.; Van der Sijde, P. Supporting entrepreneurs entering a global market. In Proceedings of the USE Conference on New Concepts for Academic Entrepreneurship, Bonn, Germany, 24–26 April 2002.

- Barley, S.R.; Tolbert, P.S. Institutionalization and structuration: Studying the links between action and institution. Organ. Stud. 1997, 18, 93–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, P.H.; Siegel, D.S. The Effectiveness of University Technology Transfer: Lessons Learned from Quantitative and Qualitative Research in the US and the UK Rensselaer Working Paper Working Paper in Economics; Number 0609; Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute: Troy, Turkey, 2006; Available online: http://www.economics.rpi.edu/workingpapers/rpi0609.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2014).

- Miller, K.; McAdam, R.; McAdam, M. A systematic literature review of university technology transfer from a quadruple helix perspective: Towards a research agenda. R&D Manag. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heide, J. Interorganizational governance in marketing channels. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, N.; Lawrence, T.B.; Hardy, C. Interor-ganizational collaboration and the dynamics of insti-tutional fields. J. Manag. Stud. 2000, 37, 23–43. [Google Scholar]

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in institutional fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAllister, D.J. Affect- and Cognition-Based Trust as Foundations for Interpersonal Cooperation in Organizations. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 24–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giddings, A. The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration; Polity Press: Oxford, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Marabelli, M.; Newell, S. Knowledge risks in organizational networks: The practice perspective. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2012, 21, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, M.; Zoller, T.D. Dealmakers in Place: Social Capital Connections in Regional Entrepreneurial Economies. Reg. Stud. 2014, 46, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenney, M.; Goe, W.R. The Role of Social Embeddedness in Professorial Entrepreneurship: A Comparison of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science at UC Berkeley and Stanford. Res. Policy 2004, 3, 691–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gertner, D.; Roberts, J.; Charles, D. University-industry Collaboration: A CoP approach to KTPs. J. Knowl. Manag. 2011, 15, 625–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lave, J.; Wenger, E. Knowledge Communities and Knowledge Collectitivies: A typology of knowledge work in groups. J. Manag. Stud. 1991, 42, 1189–1210. [Google Scholar]

- Amin, A.; Roberts, J. Knowing in action: Beyond communities of practices. Res. Policy 2008, 37, 353–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.S.; Duguid, P. Organizational learning and communities of practice: Toward a unified view of working, learning and innovation. Org. Sci. 1991, 2, 40–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, S.; Jackson, G.; Matten, D. Corporate Social Responsibility and Institutional Theory: New Perspectives on Private Governance. Socio Econ. Rev. 2012, 10, 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witt, M.A.; Redding, C. The spirits of Corporate Social Responsibility: Senior executive perceptions of the role of the firm in society in Germany, Hong Kong, Japan, South Korea and the USA. Soc. Rev. 2012, 1, 109–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubell, M.; Robins, G.; Wang, P. Network structure and institutional complexity in an ecology of water management games. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, C.; Palmer, I.; Phillips, N. Discourse as a strategic resource. Hum. Relat. 2000, 53, 1227–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilischkis, S. KT indicators: Performance of Universities and others PROs (WP2). In Knowledge Transfer Study 2010–2012; Final Report; Deliverable 5 related to Service Contract No. RTD/Dir C/C2/2010/SI.569045; Directorate-General for Research and Innovation, Innovation Union, European Commission: Luxembourg, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Tabbaa, O.; Ankrah, S. Social capital to facilitate “engineered” university-industry collaboration for technology transfer: A dynamic perspective. Technol. For. Soc. Chang. 2016, 104, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- O’shea, R.P.; Allen, T.J.; Chevalier, A.; Roche, F. Entrepreneurial Orientation, Technology Transfer and Spinoff Performance of U.S. Universities. Res. Policy 2005, 34, 994–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fini, R.; Grimaldi, R.; Sobrero, M. Factors fostering academics to start up new ventures: An assessment of Italian founders’ incentives. J. Technol. Transf. 2009, 34, 380–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Este, P.; Perkmann, M. Why do academics engage with industry? The entrepreneurial university and individual motivations. J. Technol. Transf. 2011, 36, 316–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt-Dundas, N. Research intensity and knowledge transfer activity in UK universities. Res. Policy 2012, 41, 262–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assefa, G.; Frostell, B. Social sustainability and social acceptance in technology assessment: A case study on energy technologies. Technol. Soc. 2007, 29, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parris, T.M.; Kates, R.W. Characterizing and measuring Sustainable Development. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2003, 28, 559–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, I. Social sustainability and whole development: Exploring the dimensions of sustainable development. In Sustainability and the Social Sciences; Becker, E., Jahn, T., Eds.; Zed Books: London, UK, 1998; pp. 25–36. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, J.M.; Wise, T.A.; Gallagher, K.P.; Goodwin, N.R. A Survey of Sustainable Development: Social and Economic Dimensions; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Garde-Sánchez, R.; Rodríguez-Bolivar, M.P.; López-Hernández, A.M. Online disclosure of University Social Responsibility: A comparative study of public and private US universities. Environ. Educ. Res. 2013, 19, 709–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Bolívar, M.P.; Garde-Sánchez, R.; López-Hernandez, A.M. Online disclosure of Corporate Social Responsibility in Leading Anglo-American Universities. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2013, 15, 551–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin Rubio, I.; Nogueira, J.I.; Llach, J. Innovación Abierta: Liderazgo y valores. Dyna 2013, 88, 675–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayling, J. Criminal organizations and resilience. Int. J. Law Crime Justice 2009, 37, 182–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annand, V.; Ashforth, B.C.; Joshi, M. Business as usual: The acceptance and Perpetuation of corruption in organizations. Acad. Manag. Executive 2004, 18, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.; McAdam, K.; McAdam, R. The changing university business model: A stakeholder perspective. Res. Dev. Manag. 2014, 44, 265–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.; McAdam, R.; Moffett, S.; Alexander, A.; Puthussery, P. Knowledge Transfer in Quadruple Helix Ecosystems: An Absorptive Capacity Perspective. R&D Manag. 2016, 46, 383–399. [Google Scholar]

| Innovation Steps | Stakeholders Apart from Academic Researchers | UKTO Competences |

|---|---|---|

| Research Projects | -Transfer Office staff -University managers -National and International Government Agencies -Other Universities and Research Centers -Firms |

|

| Invention and Patents | Intermediaries in Patent Offices | |

| Early Stage Development of Innovation: Innovation gap: Capital and Entrepreneurial gap | -Intermediaries in the Patent Market: suppliers and sellers of technology -Business Angels and seed capital -Dealmakers: accountants, executives | |

| Product Development | -Large and small firms (suppliers and partners of complementary assets) -Venture Capital -Other investment funds | |

| Product and Marketing | -Venture Capital -Other investment funds -Large and small firms (suppliers and partners of complementary assets) -Intermediaries specialized in global business |

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martín-Rubio, I.; Andina, D. University Knowledge Transfer Offices and Social Responsibility. Adm. Sci. 2016, 6, 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci6040020

Martín-Rubio I, Andina D. University Knowledge Transfer Offices and Social Responsibility. Administrative Sciences. 2016; 6(4):20. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci6040020

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartín-Rubio, Irene, and Diego Andina. 2016. "University Knowledge Transfer Offices and Social Responsibility" Administrative Sciences 6, no. 4: 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci6040020

APA StyleMartín-Rubio, I., & Andina, D. (2016). University Knowledge Transfer Offices and Social Responsibility. Administrative Sciences, 6(4), 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci6040020