How do Companies Invest in Corporate Social Responsibility? An Ordonomic Contribution for Empirical CSR Research

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The Current State of Empirical CSR Research

- One meta-study analyzes 52 empirical studies [3]. This meta-study concludes (a) that although the studies mainly find positive and significant correlations, the causal link between CSP and CFP is likely to be reciprocal and simultaneous. (b) The authors emphasize that the reputation the company gains from CSR activity greatly influences the strength of the CSP-CSF-link. (c) In addition, the meta-study also highlight the methodological weaknesses of all CSP-CSF studies. According their analysis, the variance of the error terms explains from 15 to 100% of the CSP-CFP link in the original studies.

- Another meta-study analyzes 82 empirical studies [4]. That meta-analysis comes up with five major results. (a) CSP has a positive impact on CSF, and this effect is stronger in the United Kingdom than in the United States. (b) Reputation gained from CSR activity has a stronger influence on the CSP-CFP link than other explaining parameters such as, for example, company audits. Philanthropic activity and environmental programs have a small effect on CFP. (c) The results of many empirical studies are, in part, due to statistical artifacts. For example, the authors show that positive effects are stronger if the studies use OLS regression or mean comparison tests. (d) Parameters such as size of firm, industry or company-specific risk, and R&D expenditure have no effect on the CSP-CFP relationship. (e) Tests suggest that CSR has a bigger influence on subjective measures and market indicators like stock market returns than on accounting-based parameters. (f) According to the meta-analysis, there is a structural discontinuity in the observation period: It shows that CSR had stronger effects in the 1960s than in the 1980s.

- The most recent meta-study examines 167 empirical studies [1]. That meta-analysis yields the following results. (a) Capital markets do not punish companies that invest in CSR. (b) The returns of pro-active CSR activities are lower than investments in innovation, capital goods, or mergers. (c) Capital markets severely punish moral misconduct of firms in the present and in the future. Consequently, CSR is profitable if it helps minimize business scandals or if it is used to prevent negative reputation effects caused by company scandals. (d) Companies with strong financial fundamentals in the past are more likely to spend money for philanthropic activities. (e) Current CSR activity predicts neither present nor future CFP. Indeed, it is highly probable that a good CFP promotes CSP, not vice versa. (f) In many cases, the reliability and validity of the CSP indicators are doubtful.

- Management of reputation. Several studies investigate the impact of reputation management on the CSP-CFP relationship. Some authors find a positive link between reputation and financial performance [5], but according to other scholars [6], the marginal returns of reputation are declining. Reputation management does not seem to be a cash cow and the effects of a good reputation on profitability are small. These micro-level studies do not analyze to what extent reputation increases (future) profits or whether reputation directly increases stock market returns [6]. Yet according to other theoretical findings, this is an important piece of information when evaluating the efficiency of capital markets: if investors focus only on the reputation of companies and not on company fundamentals, capital will accumulate inefficiently because investors waste scarce capital and create bubbles [7]. Under these circumstances, acting ‘morally’ would lead to socially undesirable results. Doing good would result in market failure.

- Management of risks. Other work argues that CSR can insure against the risk that the company’s core business activities will result in unintended but morally suspicious results, such as company scandals. According to their analysis, stakeholders (especially the general public) tend to forgive business misbehavior more easily if firms display good moral intentions but, less easily, if firms have a doubtful moral reputation [8]. Similar results are provided by studies that argue that an investment in CSR pays off for shareholders because a good CSP reduces business risks and therefore decreases volatility on the capital market [9]. According to that view, good CSR management creates strong ties with important stakeholders of the company, as well as with shareholders, that will endure even in periods of crisis.

- Management of innovation. Several empirical studies show a strong relationship between CSP, CFP, and innovation management [10,11,12]. The direction of the causality, however, is still an open question: Does CSR increase the probability of generating more and better innovations or does CSR send a positive signal to financiers so that companies can invest in more risky projects? In addition to the problem of reverse causality, the empirical studies do not reveal whether innovative companies invest more money in CSR activities. It is quite possible that the measured relationship is just a spurious correlation in the case that highly profitable and innovative firms also implement CSR and in the case that CSR does not influence the investors’ decisions and does not increase the probability of being innovative. Other authors even measure a negative and significant relationship between CSP and innovation [13]. In addition, the empirical literature has not yet asked the question whether firms explicitly use stakeholder dialogues to develop new organizational innovations such as new business mode

- Management of human resources. The theoretical CSR literature champions the idea that CSR has a positive impact on employee productivity [14]. The empirical CSR research seems to support this idea. For example, some studies research the empirical relationship between CSR and work satisfaction [15]. Furthermore, other work analyzes the effect of employee commitment on company fundamentals such as market share, competitive position, and return on investment [16]. The commitment literature provides an idea for why CSR can positively influence a firm’s human resources management. According to a much earlier study, a commitment ‘represents something beyond mere passive loyalty to an organization. It involves an active relationship with the organization such that individuals are willing to give something of themselves in order to contribute to the … organization’s well being’ [17]. Along these lines, employees who are strongly committed to their companies seem to work more productively [18,19]. In a similar fashion, some scholars apply theories of social identity and find that companies with strong CSP indicators are also more attractive employers for potential employees than firms with weak CSP indicators [20].

- Management of customer relationships. Another line of research argues that CSR activities increase customer satisfaction. Yet the empirical link is statistically not significant. The relationship varies because ‘satisfaction plays a significant role in the relationship between CSR and firm market value and … a proper combination of both CSR initiatives and product-related abilities is important’ [21]. In a micro study of 3,500 customers of three yoghurt companies, CSR activities show a statistically significant impact on purchasing behavior [22]. Customers are more likely to buy the products of companies that use CSR. In addition, buyers show more loyalty to and identification with goods that are produced by companies that engage in CSR. In addition, if CSR strengthens social identity with the firm, employees tend to be more responsive to customer needs [23]. However, consumer orientation is higher only if employees are convinced that the company has a credible customer focus. In addition, have to be convinced that consumers have a strong demand for CSR and share the same values. In general, the impact of CSR is higher if (a) the customers and the company share the same values and if (b) customers support the special areas of CSR interest [24]. Furthermore, costumers seem to be more sensitive toward negative CSR compared to information on good CSR performance.

3. An Ordonomic Conceptualization of CSR: Morality as a Factor of Production

4. Developing a Design for Empirical CSR Research

- How is CSR integrated into the organization?

- Do companies professionalize in CSR with a specialized manager who has an own budget and staff?

- To whom does the CSR division report: to another department or directly to the board?

- Are CSR policies designed to enable reciprocal cooperation? What kinds of commitments do companies use?

- How do companies commit themselves or how do they provide commitment services for their stakeholders?

- Do firms offer commitment technologies only to their closest stakeholders, such as customers, suppliers, employees, and shareholders that participate in their core business activities?

- Do companies also use commitments with other, more remote stakeholders, such as civil society organizations, environmentalist groups, politicians, or the media? Do firms use commitments on a regional, a national, or even an international level?

- Are commitments appropriate to realize cooperation?

- Do companies cultivate contacts or even dialogues with their stakeholders? How do they organize them and which stakeholders are addressed and included? With which stakeholders do companies cooperate more intensely?

- Do firms promote only their existing way of doing business or are they also interested in finding new ways of mutually beneficial cooperation? Do companies engage in dialogues only because competitors do so or do they so engage with a true purpose of discovering new ideas for their business models?

- How do companies rank the importance of stakeholder dialogues internally? Who is responsible for organizing stakeholder dialogues? Is the person in charge professionally trained to instruct other departments in the organization? How often do stakeholder dialogues take place? To what extent do companies institutionalize important dialogue functions such as mediation?

- Factor 1.The loadings of Factor 1 relate to many different variables which makes a clear interpretation difficult. Depending on the researcher’s theoretical background, different interpretations are possible. Thus, a more detailed analysis of these loadings will be the task of a prospective study.

- Factor 2. Companies with a specialized CSR manager that use CSR for management functions such as controlling, investment, finance, compliance, and investor relations more often participate in initiatives such as the Global Compact. The public criticizes both the sector and the individual firm even if firms engage in CSR activities. These companies had above-average price-to-book ratios in 2009 and paid higher dividends in 2010.

| Number of Observations: n = 42 | F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | F5 | F6 | F7 | F8 | Uniqueness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eigenvalue | 10.46 | 3.16 | 2.66 | 2.14 | 1.75 | 1.55 | 1.23 | 1.03 | |

| B2C | 0.80 | 0.31 | |||||||

| Organization of CSR: | |||||||||

| Counterpart for CSR | 0.45 | 0.38 | −0.19 | −0.47 | 0.37 | ||||

| CSR not as staff position | 0.28 | 0.66 | 0.47 | ||||||

| decentralized CSR | −0.17 | 0.75 | 0.19 | 0.35 | |||||

| CSR in a subdivision | −0.18 | 0.64 | −0.25 | 0.48 | |||||

| KPIs for CSR | 0.29 | −0.19 | 0.72 | 0.32 | |||||

| Functions of CSR: | |||||||||

| Philanthropy | 0.88 | 0.15 | |||||||

| Public Relation | 0.69 | −0.17 | 0.47 | ||||||

| Risk Management | 0.90 | −0.17 | 0.17 | 0.11 | |||||

| Marketing | 0.93 | 0.09 | |||||||

| Research and Development | 0.92 | 0.17 | 0.07 | ||||||

| Controlling | 0.86 | 0.19 | −0.21 | 0.14 | |||||

| Capex Management | 0.87 | 0.19 | |||||||

| Financial Management | 0.89 | 0.18 | 0.12 | ||||||

| Investor Relation | 0.79 | 0.18 | 0.21 | 0.17 | 0.26 | ||||

| Compliance | 0.40 | 0.51 | −0.27 | −0.19 | 0.42 | ||||

| Human Resource Management | 0.93 | 0.09 | |||||||

| Dialogues and Initiatives: | |||||||||

| Public criticizes the sector | 0.32 | 0.58 | 0.16 | 0.45 | 0.31 | ||||

| Public criticizes the company | 0.24 | 0.55 | −0.18 | 0.30 | 0.44 | 0.29 | |||

| Dialogues with stakeholders | 0.57 | 0.42 | −0.21 | 0.16 | 0.40 | ||||

| Member of the UN Global Compact | 0.30 | 0.86 | 0.15 | ||||||

| Participation on UN GC with Reports | 0.31 | 0.83 | 0.17 | 0.17 | |||||

| Participation on other CSR initiatives | 0.23 | 0.57 | 0.26 | 0.17 | −0.25 | 0.23 | 0.20 | 0.37 | |

| Company Fundamentals: | |||||||||

| Price-to-Book-ratio 2008 | 0.96 | 0.06 | |||||||

| Price-to-Book-ratio 2009 | 0.17 | 0.93 | 0.08 | ||||||

| Price-to-Book-ratio 2010 | 0.85 | 0.24 | |||||||

| Dividend Yield (%) 2008 | 0.88 | 0.19 | |||||||

| Dividend Yield (%) 2009 | 0.27 | 0.67 | 0.44 | ||||||

| Dividend Yield (%) 2010 | 0.20 | 0.22 | 0.19 | 0.76 | 0.28 | 0.22 | |||

| Return on Assets (%) 2008 | 0.16 | −0.21 | −0.42 | −0.18 | 0.33 | 0.32 | 0.50 | ||

| Return on Assets (%) 2009 | −0.17 | 0.77 | 0.33 | ||||||

| Return on Assets (%) 2010 | 0.15 | 0.17 | 0.16 | 0.75 | 0.33 | ||||

| Return on Assets (%) 2011 (forecast) | 0.32 | 0.16 | −0.16 | 0.28 | −0.39 | 0.25 | 0.54 |

- Factor 3. Companies with more centralized CSR departments participate in CSR initiatives and use CSR for investor relations. The public rarely criticizes these firms. During the observation period, the price-to-book ratio is higher and the companies paid higher dividends in 2009 and in 2010.

- Factor 4. Companies with an average CSR professionalization engage less in stakeholder dialogues, too, but show above average participation in the UN Global Compact and other CSR initiatives. These firms paid higher dividends to their owners in all observed years.

- Factor 5. Companies in a sensitive industry sector without key performance indicators to control their CSR activities are viewed more critically by the public. These companies organize CSR decentralized as a sub-division and not as an executive department. They also focus less on compliance and participate less in other CSR initiatives compared to other companies in the industry. These firms achieve above-average returns on invested capital in 2010 and 2011, but below-average returns in 2008.

- Factor 6. Firms that organize CSR as an executive department also professionalize CSR with key performance indicators (KPIs). In addition, they also engage in stakeholder dialogue and participate in other CSR initiatives. These firms have above-average returns on investment capital in 2009 and 2010, but below-average returns in 2008. The return on investment forecast is also below industry average for 2011.

- Factor 7 represents companies that also operate in a business-to-consumer market. Public opinion views these companies more critically compared to firms only operating in the B2B market. In these companies, CSR has an impact on investor relations. In the fields of public relations, risk management or compliance, however, the impact of CSR is poor. These companies had above-average returns on investment capital in 2008 but paid above-average dividends to their shareholders in 2010.

- Factor 8. Companies with decentralized CSR professionalize in risk management and R&D. However, the impact of CSR on controlling is poor. These companies had higher returns on invested capital in 2008 and 2010, and, as a forecast, also for 2011.

- Further research options inspired by factor 2. Companies with a professional CSR manager engaging in CSR in financial management and in investor relations seem to use public criticism to question existing business models. Stakeholder dialogues, the Global Compact, and other CSR initiatives seem to be instruments to generate ideas for improving the value creation process.

- Further research options inspired by factor 3. If companies professionalize their CSR activities by means of more centralized CSR management, the public tends to be less critical of them. Such professionalization of CSR might enable more productive investor relationships: investors might expect more sustainable business models and also higher future growth values, both of which facilitate refinancing sustainable investment funds.

- Further research options inspired by factor 4. Some companies do not invest in CSR because other investments yield higher returns. These companies might be under strong pressure from investors to pay high dividends. Alternative research options inspired by factor 4. Certain companies are so successful that they can afford not to engage in CSR activity. These firms seem to buy their “license to operate” with high capital costs.

- Further research options inspired by factor 5. Companies that do not connect CSR with their core business model (and hence do not control their CSR with key performance indicators) are criticized more often by the public. These companies use CSR primarily as a tool of corporate communication, i.e., they professionalize their public reputation and web sites.

- Further research options inspired by factor 6. Companies that do connect CSR to their core business model (and hence measure their CSR with key performance indicators) might use stakeholder dialogues to discover new stakeholder needs and to develop business models to meet them.

- Further research options inspired by factor 7. Companies operating in the business-to-consumer industry seem to use CSR to strengthen the relationship to their shareholders or even to attract new investors.

- Further research options inspired by factor 8. Companies that use CSR decentralized in risk management and in innovation management (and hence improve their current business model or develop new business models) also yield higher returns on invested capital.

- some companies use CSR to establish win-win cooperation with a few stakeholders,

- only few core business functions are supported by CSR projects, and

- costs of financing are higher if companies inadequately implement CSR.

5. Conclusions and Implications for Future Research

- An important insight is that not all CSR is functional. From an ordonomic perspective, it is not at all surprising that CSR shows a negative return in empirical studies if CSR activities are completely unconnected to the corporate processes of value creation, i.e., when CSR is exclusively designed as an instrument of ‘giving back to society.’

- Another important insight is that CSR can be functional if companies use moral commitments as a factor of production. This type of CSR is be strongly connected to corporate processes of value creation and, hence, also to important management functions such as, for example, risk management and innovation management. This effect should show up in the data.

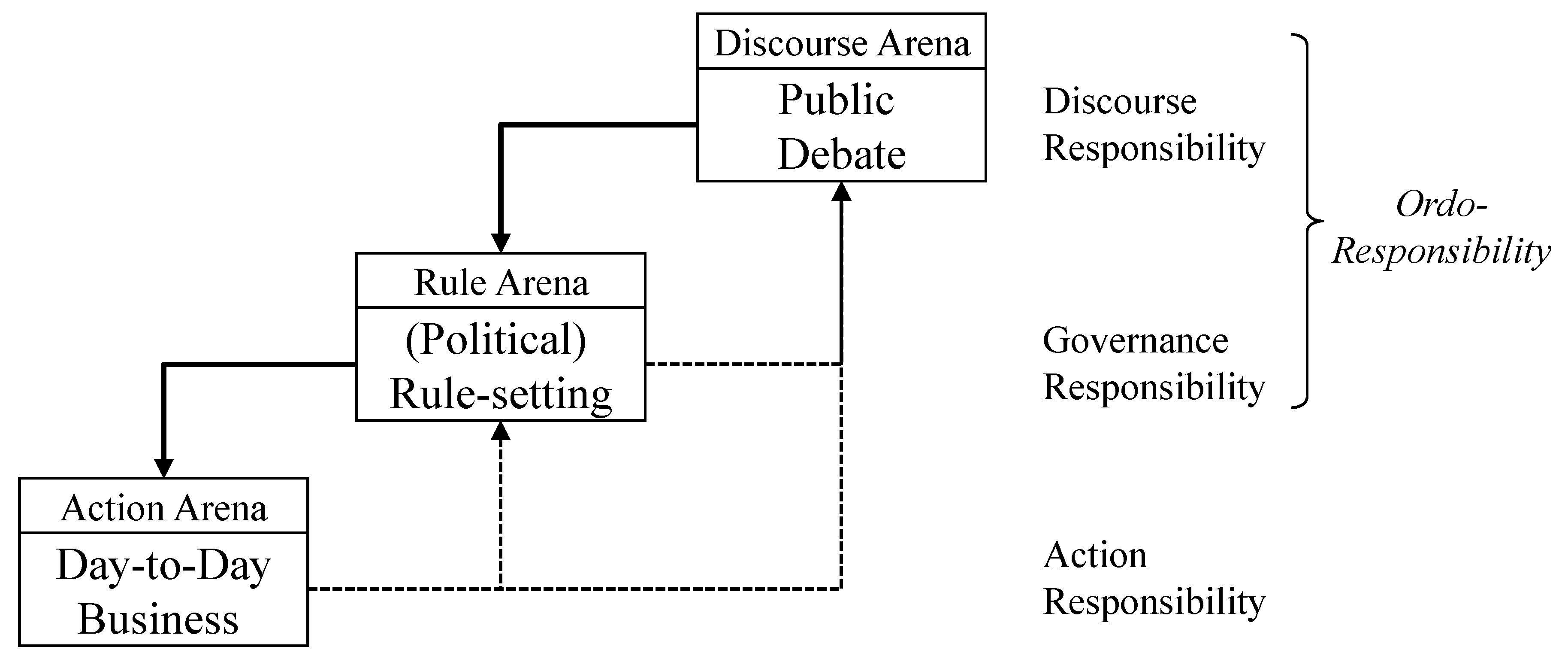

- If CSR is implemented with the help of moral commitments, companies are not only playing within the game of day-to-day business but also in the game(s) of creating new rules of day-to-day business activities. We argue that empirical CSR research should bear in mind Buchanan’s distinction between ‘choices within rules’ and ‘choices among rules’ [47]. It is not sufficient to describe the CSP-CFP link by listing what companies actually do in the ‘real’ world. A sound empirical analysis should be able to differentiate between social cooperation and the rules that lead to successful cooperation from the viewpoint of institutional (economic) theory.

- From an ordonomic perspective, the CSP-CFP literature would be well advised to distinguish not just two levels of social interaction, but three. In addition to the arena of business and the arena of rule-setting, the ordonomic perspective emphasizes that social cooperation also needs a common understanding of the win-win potential of social cooperation. Discourse, sometimes also public discourse, can create such a common awareness and is thus an important prerequisite for mutually beneficial value creation with stakeholders.

Acknowledgements

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

| Name of the Category | What do we want to measure? | The expected or unused win-win-potentials of CSR | How do we measure? | Within the Pilot Study? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Integration of CSR within the organization | ||||

| Organizational Integration of CSR | Does the way how companies integrate CSR affect CSP and/or CFP? | A centralized CSR department which is very close to the top management can easier implement CSR. | Is CSR management centralized? Is the responsible department an executive department or just a sub-division? Is there a professional manager for CSR? | Yes |

| How often does the CSR department communicate with the CEO or CFO, with risk management, R&D or controlling? | No | |||

| Is the CSR department organized as a profit or a cost center? | No | |||

| Does the CSR department use or develop KPIs? | Yes | |||

| How many people work for the CSR department and how much money can the department spend a year? | No | |||

| CSR-Functions | ||||

| Philanthropy | Can philanthropic activities influence the value creation of the company? | Philanthropy has maybe some side effects on the business model. | The CSR department finances philanthropic activities, i. e. the company spends money for charity or sponsoring. | Yes |

| Public Relation | Can CSR improve the company’s reputation? | The company is more interesting for customers who want to do something good. | The CSR department operates similar to the public relations department: it helps to improve the public image of the company and builds up a reputation as a "good corporate citizen". | Yes |

| Risk Management | Can CSR reduce the risks of value creation? | Reduced risks lead to higher profits. | The CSR department uses CSR as risk management. It tries to realize societal risks for the business model in an early stage (for example through environmental screening) and develops ideas how to reduce these risks. | Yes |

| Marketing | Can companies use CSR for marketing? | If companies use CSR as marketing, we shall expect effects that are similar to marketing campaigns. | The CSR department is similar to the marketing department: it uses CSR to place, advertise or price new products and services in a more efficient or effective way. | Yes |

| Research & Development | Can CSR increase the probability of marketable innovations? | Using CSR to receive important stakeholder information can lead to advantages in the R&D process. | The CSR department supports the research and development (R&D) for new products, services or applications. The CSR department helps in an early stage of the process of product development through information management: it submits the wishes and suggestions of important stakeholders (like customers, suppliers, employees, environmental protection organizations, etc.). | Yes |

| Controlling | Can CSR have an influence on the efficiency and effectivity of controlling? | Controlling figures are more efficient and effective because of commonly accepted rules. Employees have less incentives to defect. | The CSR department influences the controlling of the company. Improvement proposals of the CSR department become relevant through target values and indicators. | Yes |

| Capex Management | Can CSR improve investment decisions? | Implementing technologies that waste less resources have a positive effect on the cost structure. | The CSR department influences the investment activities of the company (investment management). The company uses voluntary standards like environmental or social standards to improve investment decisions. | Yes |

| Financial Management | Can CSR influence financial management? | The financial risks of the business model can be reduced if CSR leads to more stable incomes and expenditures. | The CSR department participates in finance decisions (finance management): it helps to plan and to control finances (for example: liquidity management or hedging). | Yes |

| Investor Relation | Can CSR improve the relation to investors? | Capital suppliers would be more interested in the business model of a company if CSR improves the relationship to investors. | The CSR department supports the company with the acquisition of debt or equity capital (investor relation). The CSR increases the acceptance of investors or lenders and promotes i.e. the listing in sustainability or social indexes (like MSCI ESG). | Yes |

| Compliance | Can CSR improve the compliance of the company? | Less company scandals will strengthen good relationships to important stakeholders. | The CSR department implements compliance and helps to reduce corruption, bribery and insider trading. | Yes |

| Human Resources Management | Can CSR influence the human resources management? | Companies can attract more employees who increase their efforts because the firm enhance mutual benefits through CSR management. | The CSR department supports the management of human resources through strategic or operative decisions for recruitment and for individual development. | Yes |

| Dialogues with stakeholders | ||||

| Dialogue topics | Are companies able to use dialogues to improve or develop business concepts? | Companies can use dialogues to receive important stakeholder information. Thus, criticism can be an indicator that stakeholders have unsatisfied needs that companies can meet by improved or new business models. | Do companies focus on social topics (e.g. working conditions) and environmental topics (e. g. use of resources) or on general regulatory procedures (e.g. antitrust, anti-corruption, insider trading, etc.). | No |

| Dialogue partners | Do companies voluntarily communicate with labor unions, politicians, authorities, the media and local or global NGOs? How often do they communicate? | No | ||

| Public critique | Is the company or the sector in which the company operates criticized by the public? | Yes | ||

| Member of the UN Global Compact | Is the company a member of the UN Global Compact? Does the company participate with reports? | Yes | ||

| Member of other CSR initiatives | Is the company a member of other CSR initiatives? How strong is the influence within the initiative? | Only member of other initiatives | ||

References

- Margolis, J.D.; Elfenbein, H.A.; Walsh, J.P. Does it pay to be good? A meta-analysis and redirection of research on the relationship between corporate social and financial performance. Working Paper, Ross School of Business. University of Michigan: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rost, K.; Ehrmann, T. Reporting Biases in Empirical Management Research: The Example of Win-Win Corporate Social Responsibility. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Corporate Social Responsibility, Berlin, Germany, 6 October 2012.

- Marc, O.; Schmidt, F.L.; Rynes, S.L. Corporate Social and Financial Performance: A Meta-Analysis. Organ. Stud. 2003, 24, 403–441. [Google Scholar]

- Allouche, J.; Laroche, P. A Meta-Analytical Investigation of the Relationship—Between Corporate Social and Financial Performance. 2005. Available online: http://www.reims-ms.fr/agrh/docs/actes-agrh/pdf-des-actes/2005allouche-laroche005.pdf (accessed on 11 July 2014). Also published in Revue de gestion des ressources humaines Paris, France.

- Neville, B.A.; Bell, S.J.; Mengüc, B. Corporate reputation, stakeholders and the social performance-financial performance relationship. Eur. J. Market. 2005, 39, 1184–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, J.L.F.; Sotorrío, L.L. The Creation of Value through Corporate Reputation. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 76, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, E.F.; French, K.R. Disagreement, Tastes, and Asset Prices. J. Finance Econ. 2007, 83, 667–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfrey, P.C.; Merrill, C.B.; Hansen, J.M. The Relationship between Corporate Social Responsibility and Shareholder Value: An Empirical Test of the Risk Management Hypothesis. Strat. Manag. J. 2009, 30, 425–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlitzky, M.; Benjamin, J.D. Corporate Social Performance and Firm Risk: A Meta-Analytic Review. Bus. Soc. 2001, 40, 369–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, S.; Millington, A. Does it pay to be different? An analysis of the relationship between corporate social and finance performance. Strat. Manag. J. 2008, 29, 1325–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, T.; Stinchfield, B.T.; Wood, M.S. A Triptych Inquiry: Rethinking Sustainability, Innovation, and Financial Performance. Working Paper. TI11–026 of the Duisenberg School of Finance: Duisenburg, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Guiral, A. Corporate Social Performance, Innovation Intensity and Their Impacts on Financial Performance: Evidence from Lending Decision. Working Paper. University of Alcala: Alcala, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hull, C.E.; Rothenberg, S. Firm Performance: The Interactions of Corporate Social Performance with Innovation and Industry Differentation. Strat. Manag. J. 2008, 29, 781–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattarchary, C.B.; Sen, S.; Korschun, D. Using Corporate Social Responsibilty to Win the War for Talent. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2008, 49, 37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Valentine, S.; Fleischman, G. Ethics Programs, Perceived Corporate Social Responsibility and Job Satisfaction. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 77, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, I.; Rehman, K.U.; Ali, S.I.; Yousaf, J.; Zia, M. Corporate social responsibility influences, employee commitment and organizational performance. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2010, 4, 2796–2801. [Google Scholar]

- Mowday, R.T.; Steers, R.M.; Porter, L.W. The Measurement of Organizational Commitment. J. Vocat. Behav. 1979, 14, 224–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagopoulos, N.G.; Rapp, A.A.; Vlachos, P.A. Corporate Social Performance and Employees: Construed Perceptions, Attributions and Behavioral Outcomes. Working Paper. Available online: http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1858084 (accessed on 11 July 2012).

- Brammer, S.; Millington, A.; Rayton, B. The contribution of corporate social responsibility to organizational commitment. Int. J. HRM 2007, 18, 1701–1719. [Google Scholar]

- Greening, D.W.; Turban, D.B. Corporate Social Performance as a Competitive Advantage in Attracting a Quality Workforce. Bus. Soc. 2000, 39, 254–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Bhattacharya, C.B. Corporate Social Responsibility, Customer Satisfaction, and Market Value. J. Market. 2006, 70, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Du, S.; Bhattacharya, C.B.; Sen, S. Reaping relational rewards from corporate social responsibility: The role of competitive positioning. Int. J. Res. Market. 2007, 24, 224–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korschun, D.; Bhattacharya, C.B.; Swain, S.D. When and How does Corporate Social Responsibility Encourage Customer Orientation? ESMT Working Paper 11–05, Berlin, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, S.; Bhattacharya, C.B. Does Doing Good Always Lead to Doing Better? Consumer Reactions to Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Market. Res. 2001, 38, 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin-Hi, N.; Müller, K. The CSR Bottom Line: Preventing Corporate Social Irresponsibility. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1828–1936. [Google Scholar]

- Beckmann, M.; Hielscher, S.; Pies, I. Commitment Strategies for Sustainability. How Corporations can create Value through New Governance. In Academy of Management Best Paper Proceedings, San Antonio, TX, USA; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Beckmann, M.; Hielscher, S.; Pies, I. Governance Strategies for Corporate Sustainability: How Business Firms Can Transform Trade-Offs into Win-Win Outcomes. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2014, 23, 18–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hielscher, S. Morality as a Factor of Production: Moral Commitments as Strategic Risk Management. In Corporate Citizenship and New Governance: The Political Role of Corporations; Koslowski, P., Ed.; Dordrecht and Heidelberg: Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 117–132. [Google Scholar]

- Hielscher, S. Vita consumenda oder Vita activa?—Edmund Phelps und die moralische Qualität der Marktwirtschaft. In Edmund Phelps, Konzepte der Gesellschaftstheorie; Pies, I., Leschke, M., Eds.; Mohr Siebeck: Tübingen, Germany, 2012. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Pies, I.; Hielscher, S.; Beckmann, M. Moral Commitments and the Societal Role of Business: An Ordonomic Approach to Corporate Citizenship. Bus. Ethics Q. 2009, 19, 375–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pies, I.; Hielscher, S.; Beckmann, M. Value Creation, Management Competencies, and Global Corporate Citizenship: An Ordonomic Approach to Business Ethics in the Age of Globalization. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 64, 265–278. [Google Scholar]

- Pies, I.; Beckmann, M.; Hielscher, S. The Political Role of the Business Firm: An Ordonomic Re-Conceptualization of an Aristotelian Idea. Bus. Soc. 2014, 53, 226–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hielscher, S.; Pies, I.; Valentinov, V. 2012. How to Foster Social Progress: An Ordonomic Perspective on Institutional Change. J. Econ. Issues 2012, 46, 779–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pies, I.; Beckmann, M.; Hielscher, S. Competitive Markets, Corporate Firms, and New Governance—An Ordonomic Conceptualization. In Corporate Citizenship and New Governance. The Political Role of Corporations; Pies, I., Koslowski, P., Eds.; Dordrecht and Heidelberg: Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 171–188. [Google Scholar]

- Mises, L.v. Liberalism: In the Classical Tradition; Cobden Press and the Foundation for Economic Education Irvington-on-Hudson: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hazlitt, H. The Foundations of Morality; The Foundation for Economic Education Irvington-on-Hudson: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Pies, I. Ordnungspolitikin der Demokratie: Ein ökonomischer Ansatz diskursiver Politikberatung; Mohr Siebeck: Tübingen, Germany, 2000. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, M. The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits. New York Times Magazine, 13 September 1970; Issue 122–126, 32–33. [Google Scholar]

- Schelling, T.C. The Strategy of Conflict; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Pies, I. Moral als Produktionsfaktor: Ordonomische Schriften zur Unternehmensethik; wvb: Berlin, Germany, 2009. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Beckmann, M.; Pies, I. Ordo—Responsibility-Conceptual Reflections towards a Semantic. In novation. In Corporate Citizenship, Contractarianism and Ethical Theory on Philosophical Foundations of Business Ethics; Conill, J., Lütge, C., Schönwälder-Kuntze, T., Eds.; Ashgate: Farnham, UK, 2008; pp. 87–115. [Google Scholar]

- Balfour, D.L.; Wechsler, B. Organizational Commitment: Antecedents and Outcomes in Public Organizations. Publ. Prod. Manag. Rev. 1996, 19, 256–277. [Google Scholar]

- Rawls, J. Political Liberalism, expended ed.; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993; reprint 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Backhaus, K.; Erichson, B.; Plinke, W.; Weiber, R. Multivariate Analysemethoden—Eine anwendungsorientierte Einführung, 11th ed.; Springer Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2006. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay, P. Multivariate Statistical Analysis; World Scientific: Danvers, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ariva.de. Fundamental. Available online: www.ariva.de (accessed on 10 November 2011).

- Buchanan, J.M.; Dollisson, R.D.; Tullock, G. Toward a Theory of the Rent-Seeking Society; A&M University Economics Series; College Station: Texas, TX, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Will, M.G.; Hielscher, S. How do Companies Invest in Corporate Social Responsibility? An Ordonomic Contribution for Empirical CSR Research. Adm. Sci. 2014, 4, 219-241. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci4030219

Will MG, Hielscher S. How do Companies Invest in Corporate Social Responsibility? An Ordonomic Contribution for Empirical CSR Research. Administrative Sciences. 2014; 4(3):219-241. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci4030219

Chicago/Turabian StyleWill, Matthias Georg, and Stefan Hielscher. 2014. "How do Companies Invest in Corporate Social Responsibility? An Ordonomic Contribution for Empirical CSR Research" Administrative Sciences 4, no. 3: 219-241. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci4030219

APA StyleWill, M. G., & Hielscher, S. (2014). How do Companies Invest in Corporate Social Responsibility? An Ordonomic Contribution for Empirical CSR Research. Administrative Sciences, 4(3), 219-241. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci4030219