When Intentions Stall: Exploring the Quasi-Longitudinal Divide Between Entrepreneurial Intention and Action

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Meaning and Determinants of Entrepreneurial Intention

2.1.1. Personality Traits and Their Impact on Entrepreneurial Intention

2.1.2. Motivational Factors and Their İmpact on Entrepreneurial İntention

2.1.3. The İnfluence of Personal and Family Background on Entrepreneurial İntention

2.2. The Intention-Action Gap

2.3. Factors Influencing the Evolution of Entrepreneurial Intention and Action

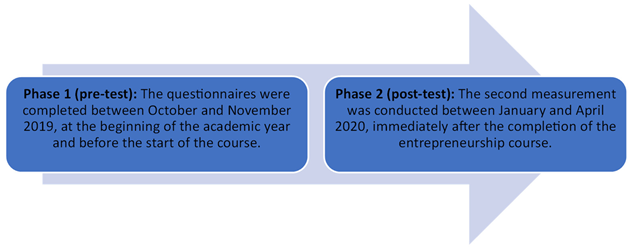

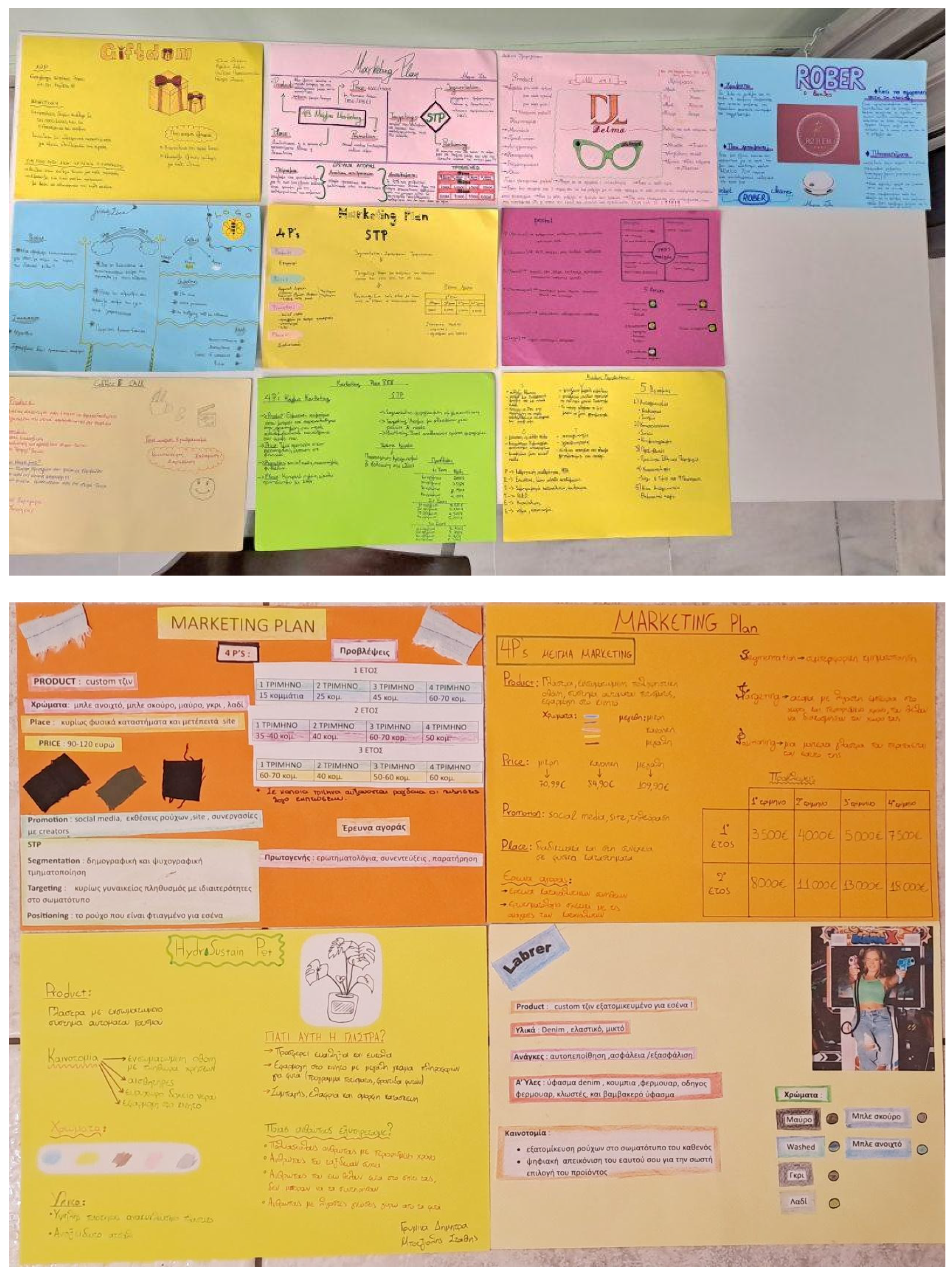

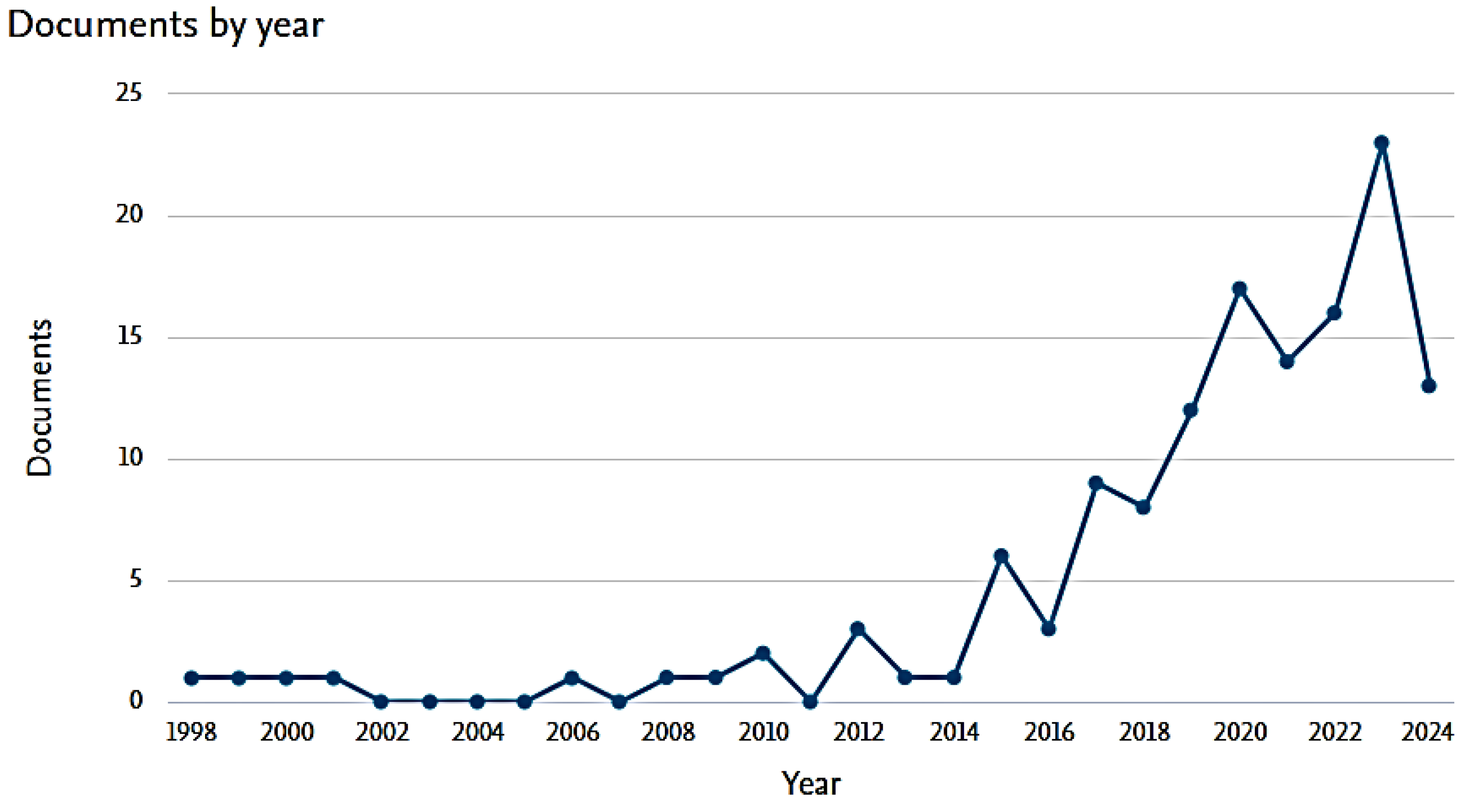

3. Materials and Methods

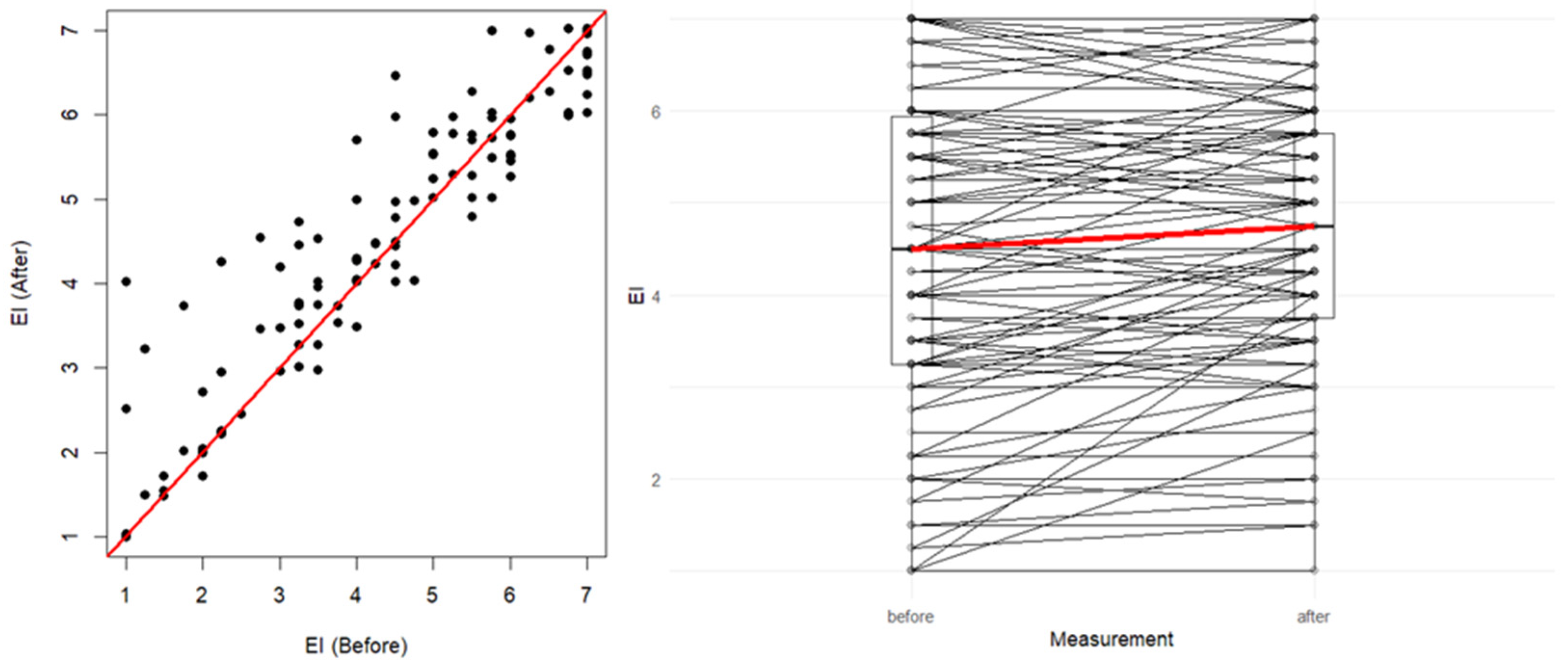

4. Results

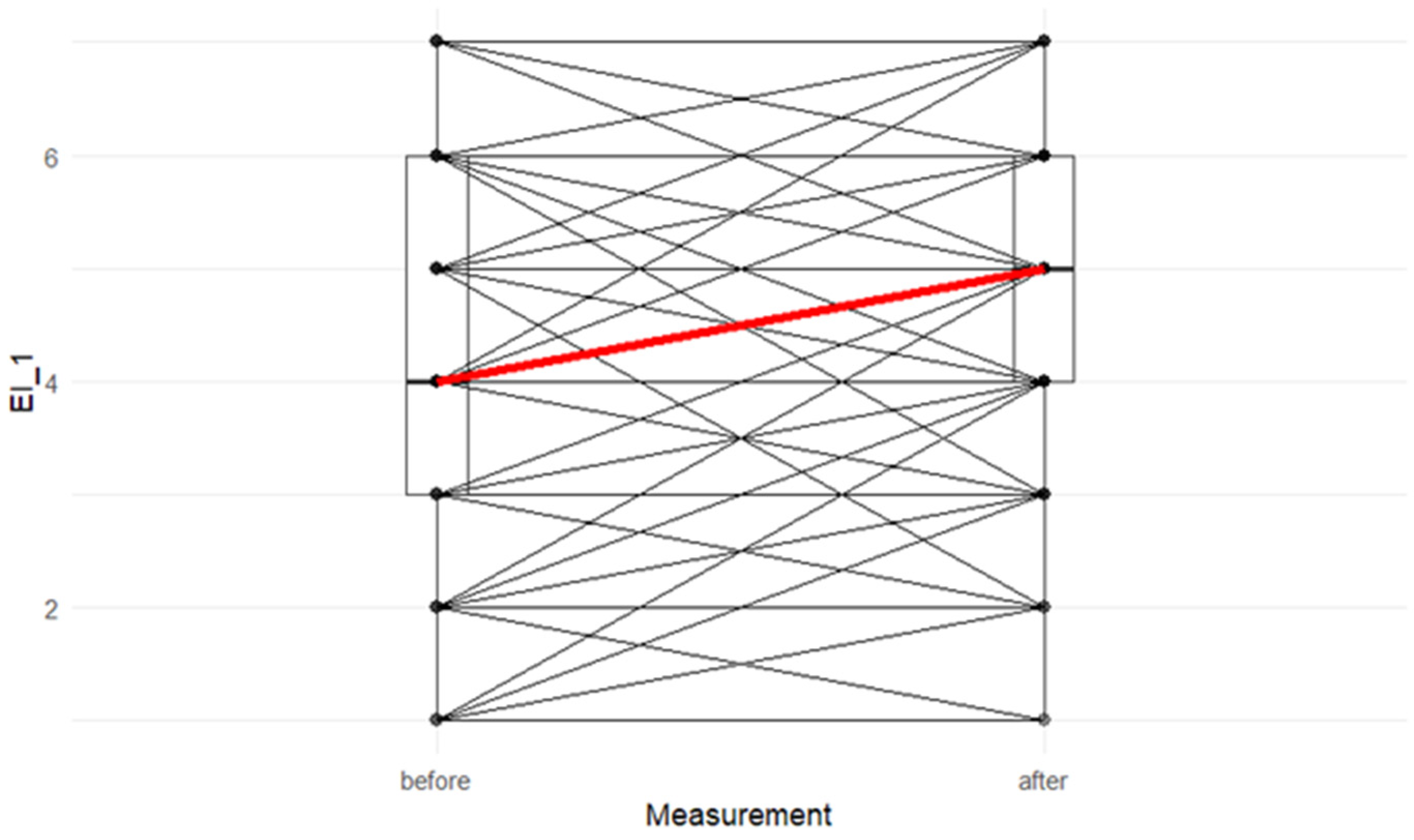

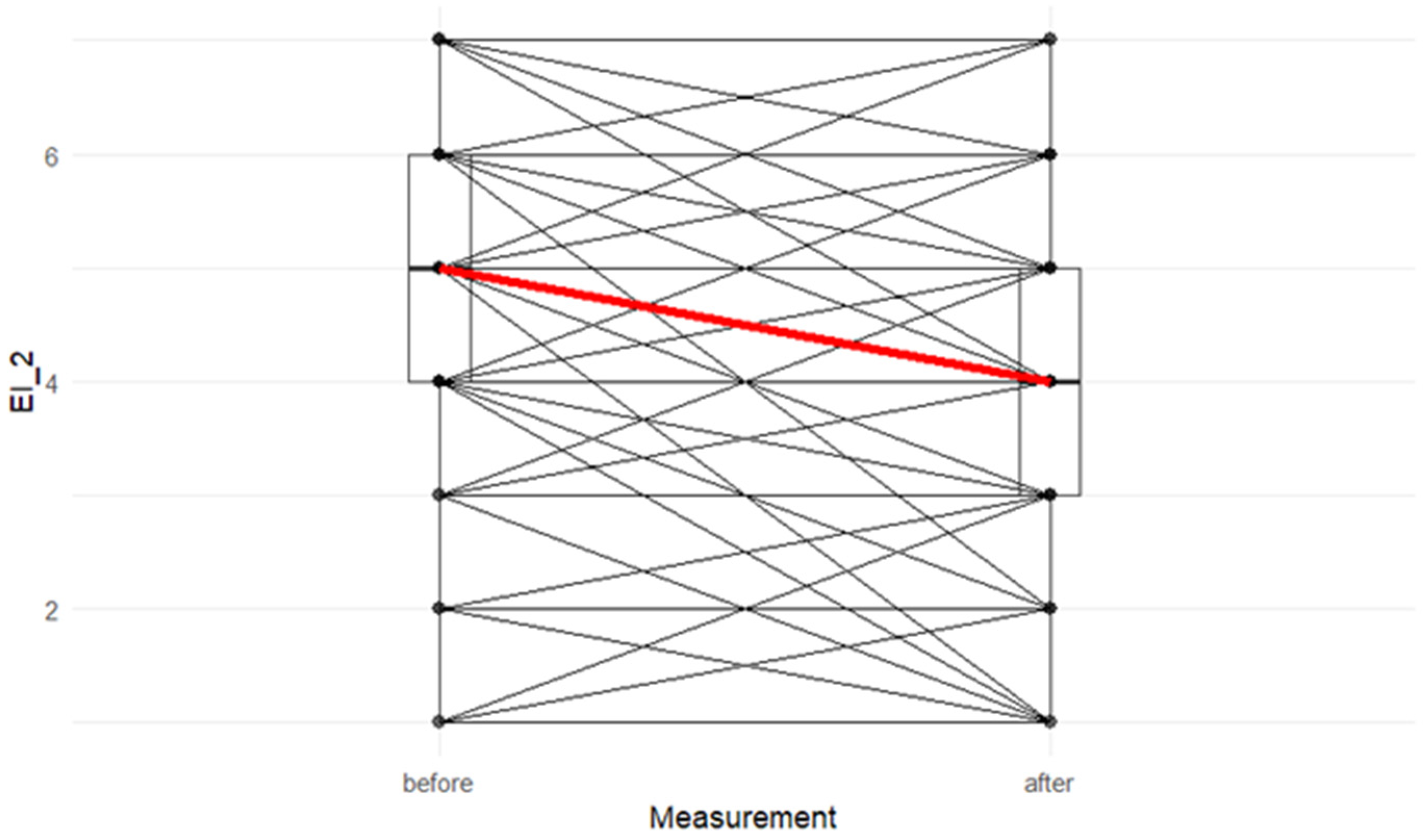

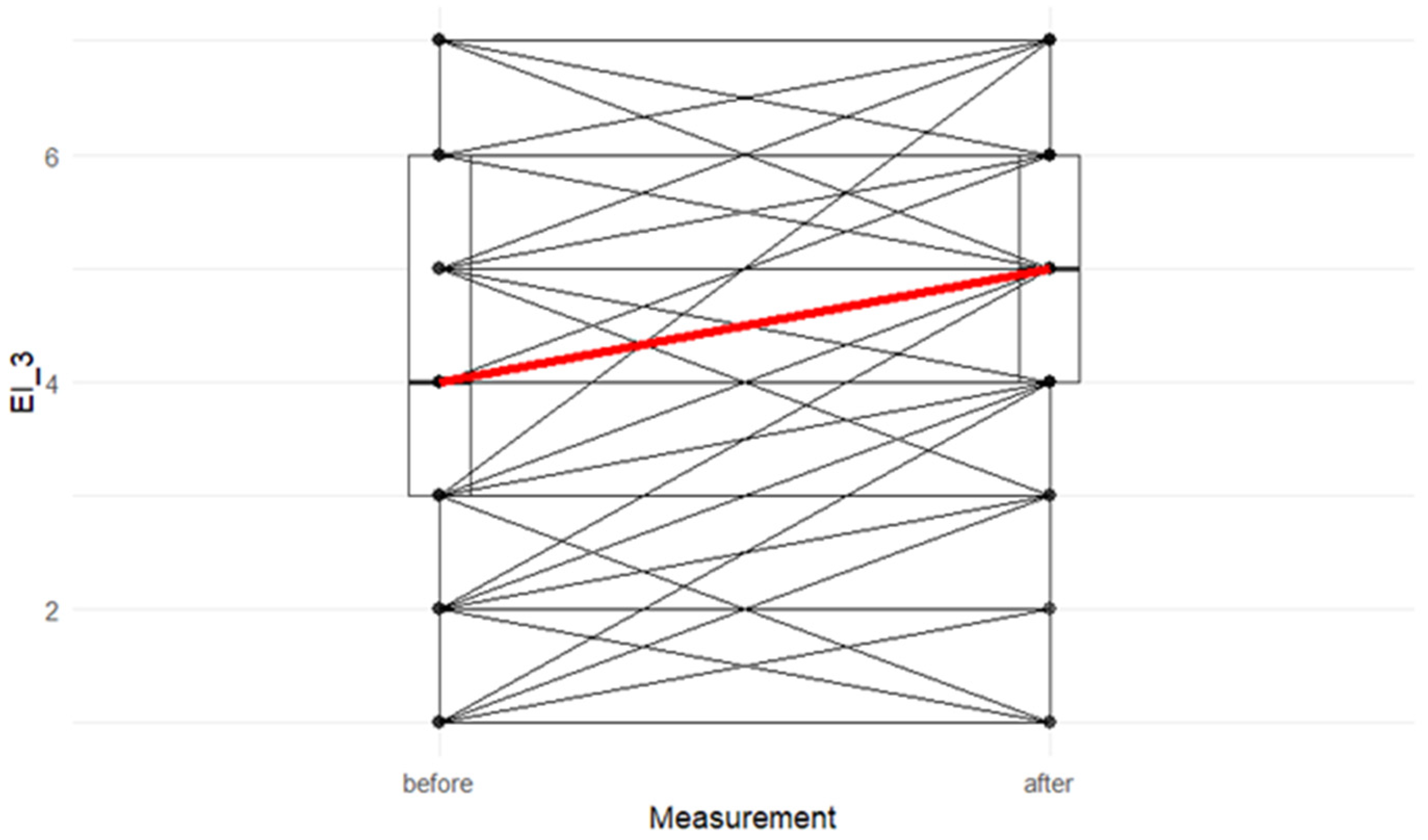

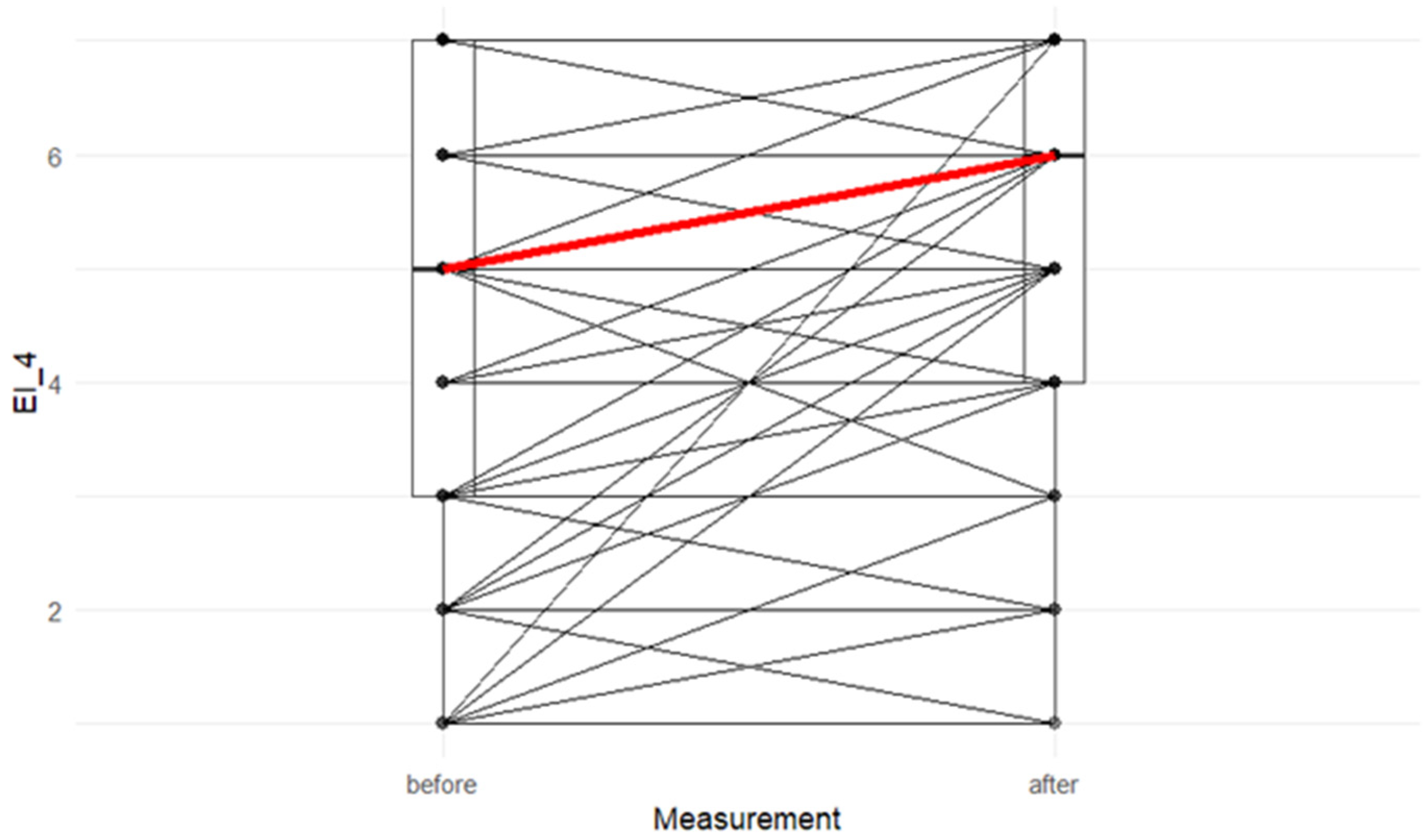

Quantitative Research Results

5. Discussion

6. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Definition |

| EI | Entrepreneurial Intention |

| TPB | Theory of Planned Behaviour |

| EE | Entrepreneurship Education |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| VIF | Variance Inflation Factor |

| R2 | Coefficient of Determination |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| α (Cronbach’s α) | Internal Consistency Coefficient |

| d (Cohen’s d) | Effect Size (Standardized Mean Difference) |

| SME | Small and Medium-sized Enterprise |

| HEI | Higher Education Institution |

Appendix A

Appendix B

| Study | Sample & Context | Research Design | Theoretical Framework | Main Variables Examined | Key Findings | Limitations Identified in Original Study | What the Present Study Adds (Novelty) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Souitaris et al. (2007) | University students attending an entrepreneurship program (EU) | Pre–post quantitative design | EE theories, Attitude–Intention logic | Entrepreneurial intention; attitudinal changes | EE increases intention but not linked to real behavior | No follow-up; no behavioral indicators; no personality variables | Provides updated empirical evidence with real-course context and integrates personality moderators |

| Shirokova et al. (2016) | 17,000+ students in 21 countries | Cross-sectional + multi-level | Institutional theory | University environment; family background; uncertainty avoidance | Institutional factors shape intention–action conversion | No pre–post design; country-level confounds | Uses controlled pre–post measurement in a single institutional context to isolate educational impact |

| Nabi et al. (2017) (Systematic Review) | 159 EE studies | Systematic literature review | EE evaluation frameworks | EE outcomes, intentions, long-term effects | Highlights lack of behavioral evidence and long-term tracking | No primary data; calls for real-course empirical evidence | Responds directly to review’s call by providing real student data + intention evolution analysis |

| Bae et al. (2014) | Meta-analysis of 73 studies | Meta-analytic | TPB, EE theories | EE → EI relationship | Small positive effect; large heterogeneity | No dynamics; no intention–action measurement | Adds dynamic perspective (pre–post change) and investigates drivers of intention shifts |

| Present Study (Your Study) | University students in Greece in a real entrepreneurship course | Pre–post quantitative design | TPB + personality + contextual factors | Attitude, SN, PBC, personality, gender, family business background | identifies key drivers of intention change and practical determinants of intention–action transition | Addresses gaps: lack of dynamic empirical designs, lack of intention-change predictors, absence of integrated TPB-personality-context models | Unique integrated model; dynamic evidence of intention evolution; practical insights for designing EE that reduces the intention–action gap; first study in Greece combining TPB, personality, and contextual moderators in a pre–post real-course context. |

| Santos et al. (2019) | University students | Qualitative | Socio-cultural lens | Identity, self-discovery, social norms | Universities shape identity formation | Qualitative only; no outcome measures | Combines psychological, contextual, and identity-related influences into a quantitative model |

| Ferreira et al. (2023) | Young adults | Quantitative | TPB | Attitudes, SN, PBC | TPB explains intention variance | No educational context; no dynamic design | Integrates TPB in an educational intervention context and examines intention evolution |

| Asenkerschbaumer et al. (2024) | Student entrepreneurs | Survey + ecosystem focus | Ecosystem theory | Social support; networks; self-efficacy | Social support enhances intentions | No temporal dimension | Shows how such factors influence pre–post intention changes during a course |

| Haddad et al. (2022) | University students | Survey | Cultural dimensions + TPB | Cultural traits; risk propensity; EI | Cultural traits and risk affect EI | No intervention; no behavior link | Adds educational intervention + intention-shift analysis within TPB framework |

| Botezat et al. (2022) | Longitudinal student data | Multi-wave | TPB + contextual | EI over time; pandemic effects | EI changes during crisis | External shock context; limited generalizability | Measures intention change under normal educational conditions |

| Xanthopoulou & Sahinidis (2025) | Greek students (pre–post) | Mixed-methods; longitudinal components | EE + intention evolution | EI dynamics, teaching methods, support | Significant EI changes across semesters | Mixed-method but not fully TPB integrated | Expands with broader set of predictors (personality, context, family background) |

References

- Abbasianchavari, A., & Moritz, A. (2021). The impact of role models on entrepreneurial intentions and behaviour: A review of the literature. Management Review Quarterly, 71(1), 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adetola, V., Lin, F., Yuan, S., & Reeve, H. (2018). Building flexibility estimation and control for grid ancillary services. Energy Procedia, 150(1), 289–296. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, T., Chandran, V. G. R., Klobas, J. E., Liñán, F., & Kokkalis, P. (2020). Entrepreneurship education programmes: How learning, inspiration and resources affect intentions for new venture creation in a developing economy. The International Journal of Management Education, 18(1), 100327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behaviour. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jubari, I., Hassan, A., & Hashim, J. (2017). The role of autonomy as a predictor of entrepreneurial intention among university students in Yemen. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 30(3), 325–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mamary, Y. H., & Alshallaqi, M. (2022). Impact of autonomy, innovativeness, risk-taking, proactiveness, and competitive aggressiveness on students’ intention to start a new venture. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, 7(4), 100239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, A., & Garrod, B. (2024). Drivers and inhibitors of entrepreneurship in Europe’s Outermost Regions: Implications for entrepreneurship education. The International Journal of Management Education, 22(2), 100975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsyouf, A., Ishak, A. K., Lutfi, A., Alhazmi, F. N., & Al-Okaily, M. (2022). The role of personality and top management support in continuance intention to use electronic health record systems among nurses. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(17), 11125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, T., Díaz Tautiva, J. A., Zaheer, M. A., & Heidler, P. (2024). Entrepreneurial intentions: Entrepreneurship education programs, cognitive motivational factors of planned behaviour, and business incubation centres. Education Sciences, 14(9), 983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, M., Clauss, T., & Issah, W. B. (2022). Entrepreneurial orientation and new venture performance in emerging markets: The mediating role of opportunity recognition. Review of Managerial Science, 16(3), 769–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparicio, S., Turro, A., & Noguera, M. (2020). Entrepreneurship and intrapreneurship in social, sustainable, and economic development: Opportunities and challenges for future research. Sustainability, 12(21), 8958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asenkerschbaumer, M., Greven, A., & Brettel, M. (2024). The role of entrepreneurial imaginativeness for implementation intentions in new venture creation. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 20(1), 55–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayob, A. H. (2021). Institutions and student entrepreneurship: The effects of economic conditions, culture and education. Educational Studies, 47(6), 661–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, T. J., Qian, S., Miao, C., & Fiet, J. O. (2014). The relationship between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intentions: A meta-analytic review. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 38(2), 217–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba-Sánchez, V., & Atienza-Sahuquillo, C. (2017). Entrepreneurial motivation and self-employment: Evidence from expectancy theory. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 13(1), 1097–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba-Sánchez, V., & Atienza-Sahuquillo, C. (2018). Entrepreneurial intention among engineering students: The role of entrepreneurship education. European Research on Management and Business Economics, 24(1), 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba-Sánchez, V., Mitre-Aranda, M., & del Brío-González, J. (2022). The entrepreneurial intention of university students: An environmental perspective. European Research on Management and Business Economics, 28(2), 100184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbero, J., Diukanova, O., Gianelle, C., Salotti, S., & Santoalha, A. (2024). Technologically related diversification: One size does not fit all European regions. Research Policy, 53(3), 104973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyhan, B., & Findik, D. (2018). Student and graduate entrepreneurship: Ambidextrous universities create more nascent entrepreneurs. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 43(5), 1346–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogatyreva, K., & Shirokova, G. (2017). From entrepreneurial aspirations to founding a business: The case of Russian students. Foresight and STI Governance, 11(3), 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botezat, E. A., Constăngioară, A., Dodescu, A. O., & Pop-Cohuţ, I. C. (2022). How stable are students’ entrepreneurial intentions in the COVID-19 pandemic context? Sustainability, 14(9), 5690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, J. C., & Sequeira, J. M. (2007). Prior family business exposure as intergenerational influence and entrepreneurial intent: A theory of planned behaviour approach. Journal of Business Research, 60(10), 1090–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras-Barraza, N., Espinosa-Cristia, J. F., Salazar-Sepulveda, G., & Vega-Muñoz, A. (2021). Entrepreneurial intention: A gender study in business and economics students from Chile. Sustainability, 13(9), 4693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidsson, P., & Honig, B. (2003). The role of social and human capital among nascent entrepreneurs. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(3), 301–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debarliev, S., Janeska-Iliev, A., Stripeikis, O., & Zupan, B. (2022). What can education bring to entrepreneurship? Formal versus non-formal education. Journal of Small Business Management, 60(1), 219–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa-Filho, J. M., Matos, S., da Silva Trajano, S., & de Souza Lessa, B. (2020). Determinants of social entrepreneurial intentions in a developing country context. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 14(1), e00207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, B. R., & Dadvari, A. (2017). The influence of the dark triad on the relationship between entrepreneurial attitude orientation and entrepreneurial intention: A study among students in Taiwan University. Asia Pacific Management Review, 22(4), 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y., Pang, L., & Fu, L. (2019). Research on the influencing factors of entrepreneurial intentions based on the mediating effect of self-actualisation. International Journal of Innovation Science, 11(3), 388–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, H. (2013). The value of cognitive values. Philosophy of Science, 80(5), 796–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvouletý, O., Mühlböck, M., Warmuth, J., & Kittel, B. (2018). ‘Scarred’ young entrepreneurs: Exploring young adults’ transition from former unemployment to self-employment. Journal of Youth Studies, 21(9), 1159–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M. S., Salam, M., ur Rehman, S., Fayolle, A., Jaafar, N., & Ayupp, K. (2018). Impact of support from social network on entrepreneurial intention of fresh business graduates: A structural equation modelling approach. Education + Training, 60(4), 335–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayolle, A., & Gailly, B. (2015). The impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial attitudes and intention: Hysteresis and persistence. Journal of Small Business Management, 53(1), 75–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J. J., Fernandes, C. I., & Veiga, P. M. (2023). The role of entrepreneurial ecosystems in SME internationalisation. Journal of Business Research, 157(1), 113603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgescu, M. A., & Herman, E. (2020). The impact of the family background on students’ entrepreneurial intentions: An empirical analysis. Sustainability, 12(11), 4775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gielnik, M. M., Zacher, H., & Wang, M. (2018). Age in the entrepreneurial process: The role of future time perspective and prior entrepreneurial experience. Journal of Applied Psychology, 103(10), 1067–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gieure, C., del Mar Benavides-Espinosa, M., & Roig-Dobón, S. (2020). The entrepreneurial process: The link between intentions and behavior. Journal of Business Research, 112(1), 541–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorgievski, M. J., Stephan, U., Laguna, M., & Moriano, J. A. (2018). Predicting entrepreneurial career intentions: Values and the theory of planned behaviour. Journal of Career Assessment, 26(3), 457–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haddad, C. R., Nakić, V., Bergek, A., & Hellsmark, H. (2022). Transformative innovation policy: A systematic review. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 43, 14–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanage, R., Davies, M. A. P., Stenholm, P., & Scott, J. M. (2024). Extending the theory of planned behaviour—A longitudinal study of entrepreneurial intentions. Entrepreneurship Research Journal, 14(3), 1223–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haus, I., Steinmetz, H., Isidor, R., & Kabst, R. (2013). Gender effects on entrepreneurial intention: A meta-analytical structural equation model. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 5(2), 130–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hägg, G., & Kurczewska, A. (2019). Who is the student entrepreneur? Understanding the emergent adult through the pedagogy and andragogy interplay. Journal of Small Business Management, 57(1), 130–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrekson, M., & Stenkula, M. (2010). Entrepreneurship and public policy. In Handbook of entrepreneurship research: An interdisciplinary survey and introduction (pp. 595–637). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, D. K., Burmeister-Lamp, K., Simmons, S. A., Foo, M. D., Hong, M. C., & Pipes, J. D. (2019). “I know I can, but I don’t fit”: Perceived fit, self-efficacy, and entrepreneurial intention. Journal of Business Venturing, 34(2), 311–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoubli, C. E., & Gharbi, L. (2024). Investigating how social context moderates the relationship between intentions and behaviours in student entrepreneurship: Case of Tunisian students. The International Journal of Management Education, 22(1), 100918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, M., Scherer, R., & Schroeders, U. (2015). Students’ self-concept and self-efficacy in the sciences: Differential relations to antecedents and educational outcomes. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 41(1), 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X., & Sun, Y. (2015). Research article study on constructing an education platform for innovation and entrepreneurship of university students. Research Journal of Applied Sciences, Engineering and Technology, 9(10), 824–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwal, S., Pitafi, A. H., Pitafi, A., Nadeem, M. A., Younis, A., & Chong, R. (2019). China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) development projects and entrepreneurial potential of locals. Journal of Public Affairs, 19(4), e1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kautonen, T., Van Gelderen, M., & Fink, M. (2015). Robustness of the theory of planned behaviour in predicting entrepreneurial intentions and actions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 39(3), 655–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kefis, V., & Xanthopoulou, P. (2015). Teaching entrepreneurship through e-learning: The implementation in schools of social sciences and humanities in Greece. International Journal of Sciences, 4(8), 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, S. P., Kerr, W. R., & Xu, T. (2018). Personality traits of entrepreneurs: A review of recent literature. Foundations and Trends® in Entrepreneurship, 14(3), 279–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobylińska, U. (2022). Attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived control versus contextual factors influencing the entrepreneurial intentions of students from Poland. WSEAS Transactions on Business and Economics, 19(1), 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koe, W. L., Krishnan, R., & Alias, N. E. (2021). The influence of self-efficacy and individual entrepreneurial orientation on technopreneurial intention among Bumiputra undergraduate students. Asian Journal of University Education, 17(4), 490–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koe, W. L., Sa’ari, J. R., Majid, I. A., & Ismail, K. (2012). Determinants of entrepreneurial intention among millennial generation. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences, 40(1), 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, N. F. (1993). The impact of prior entrepreneurial exposure on perceptions of new venture feasibility and desirability. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 18(1), 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, N. F., Mestwerdt, S., & Kickul, J. (2024). Entrepreneurial thinking: Rational vs. intuitive. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 25(5/6), 942–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, N. F., Jr., Reilly, M. D., & Carsrud, A. L. (2000). Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Business Venturing, 15(5–6), 411–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küttim, M., Kallaste, M., Venesaar, U., & Kiis, A. (2014). Entrepreneurship education at university level and students’ entrepreneurial intentions. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences, 110(1), 658–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T. T., Nguyen, T. H., Ha, S. T., Nguyen, Q. K., Tran, N. M., & Duong, C. D. (2023). The effect of entrepreneurial education on entrepreneurial intention among master students: Prior self-employment experience as a moderator. Central European Management Journal, 31(1), 30–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, F., & Chen, Y. W. (2009). Development and cross-cultural application of a specific instrument to measure entrepreneurial intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(3), 593–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, F., & Fayolle, A. (2015). A systematic literature review on entrepreneurial intentions: Citation, thematic analyses, and research agenda. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 11(1), 907–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, F., Rodríguez-Cohard, J. C., & Rueda-Cantuche, J. M. (2011). Factors affecting entrepreneurial intention levels: A role for education. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 7(1), 195–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lortie, J., & Castogiovanni, G. (2015). The Theory of Planned Behaviour in entrepreneurship research: What we know and future directions. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 11(1), 935–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, G., Song, Y., & Pan, B. (2021). How university entrepreneurship support affects college students’ entrepreneurial intentions: An empirical analysis from China. Sustainability, 13(6), 3224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luc, P. T. (2020). The influence of personality traits on social entrepreneurial intention among owners of civil society organisations in Vietnam. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 40(3), 291–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lungu, A. E. (2022). Comparative analysis of entrepreneurial innovation factors in 25 national states. ANDULI. Revista Andaluza de Ciencias Sociales, 21(1), 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maes, J., Leroy, H., & Sels, L. (2014). Gender differences in entrepreneurial intentions: A TPB multi-group analysis at factor and indicator level. European Management Journal, 32(5), 784–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheshwari, G., Kha, K. L., & Arokiasamy, A. R. A. (2023). Factors affecting students’ entrepreneurial intentions: A systematic review (2005–2022) for future directions in theory and practice. Management Review Quarterly, 73(4), 1903–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahfud, T., Triyono, M. B., Sudira, P., & Mulyani, Y. (2020). The influence of social capital and entrepreneurial attitude orientation on entrepreneurial intentions: The mediating role of psychological capital. European Research on Management and Business Economics, 26(1), 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamun, A. A., Nawi, N. B. C., Mohiuddin, M., Shamsudin, S. F. F. B., & Fazal, S. A. (2017). Entrepreneurial intention and startup preparation: A study among business students in Malaysia. Journal of Education for Business, 92(6), 296–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maresch, D., Harms, R., Kailer, N., & Wimmer-Wurm, B. (2016). The impact of entrepreneurship education on the entrepreneurial intention of students in science and engineering versus business studies university programmes. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 104(1), 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meoli, A., Fini, R., Sobrero, M., & Wiklund, J. (2020). How entrepreneurial intentions influence entrepreneurial career choices: The moderating influence of social context. Journal of Business Venturing, 35(3), 105982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molino, M., Dolce, V., Cortese, C. G., & Ghislieri, C. (2018). Personality and social support as determinants of entrepreneurial intention: Gender differences in Italy. PLoS ONE, 13(6), e0199924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, D. B., Usher, E. L., & Chen, J. A. (2017). Reconceptualising the sources of teaching self-efficacy: A critical review of emerging literature. Educational Psychology Review, 29(1), 795–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabi, G., Liñán, F., Fayolle, A., Krueger, N., & Walmsley, A. (2017). The impact of entrepreneurship education in higher education: A systematic review and research agenda. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 16(2), 277–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neneh, B. N. (2014). An assessment of entrepreneurial intention among university students in Cameroon. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 5(20), 542–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, T. (2022). The impact of green entrepreneurship on economic, social, and environmental development [Doctoral dissertation, Zentrale Hochschulbibliothek]. Available online: https://www.eksh.org/fileadmin/redakteure/downloads/publikationen/dissertation-neumann-kumulativ-2023.pdf (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Nowiński, W., & Haddoud, M. Y. (2019). The role of inspiring role models in enhancing entrepreneurial intention. Journal of Business Research, 96(1), 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, N. A., Shah, N. U., Hasan, N. A., & Ali, M. H. (2019). The influence of self-efficacy, motivation, and independence on students’ entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Nusantara Studies, 4(2), 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otache, I., Umar, K., Audu, Y., & Onalo, U. (2021). The effects of entrepreneurship education on students’ entrepreneurial intentions: A longitudinal approach. Education + Training, 63(7/8), 967–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozaralli, N., & Rivenburgh, N. K. (2016). Entrepreneurial intention: Antecedents to entrepreneurial behaviour in the USA and Turkey. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 6(1), 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Macías, N., Fernández-Fernández, J. L., & Vieites, A. R. (2022). Analyzing the past to prepare for the future: A review of literature on factors with influence on entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of International Entrepreneurship, 20(1), 52–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittaway, L., & Cope, J. (2007). Entrepreneurship education: A systematic review of the evidence. International Small Business Journal, 25(5), 479–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polit, D. F., & Beck, C. T. (2010). Generalisation in quantitative and qualitative research: Myths and strategies. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 47(11), 1451–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Politis, D., Winborg, J., & Dahlstrand, Å. L. (2012). Exploring the resource logic of student entrepreneurs. International Small Business Journal, 30(6), 659–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pornsakulvanich, V. (2017). Personality, attitudes, social influences, and social networking site usage predicting online social support. Computers in Human Behavior, 76(1), 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramoglou, S., Gartner, W. B., & Tsang, E. W. (2020). Who is an entrepreneur? is (still) the wrong question. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 13(1), e00168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauch, A., & Frese, M. (2007). Let’s put the person back into entrepreneurship research: A meta-analysis on the relationship between business owners’ personality traits, business creation, and success. European Journal of work and organizational psychology, 16(4), 353–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuel Johnmark, D., Munene, J. C., & Balunywa, W. (2016). Robustness of personal initiative in moderating entrepreneurial intentions and actions of disabled students. Cogent Business & Management, 3(1), 1169575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robson, G. D. (2010). Continuous process improvement. Simon & Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Roos, A. (2021). Reproducing gender—The spatial context of gender in entrepreneurship. Acta Universitatis Agriculturae Sueciae, 2021(8). Available online: https://publications.slu.se/?file=publ/show&id=109896 (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Ruiz-Rosa, I., Gutiérrez-Taño, D., & García-Rodríguez, F. J. (2020). Social entrepreneurial intention and the impact of COVID-19 pandemic: A structural model. Sustainability, 12(17), 6970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusu, V. D., Roman, A., & Tudose, M. B. (2022). Determinants of entrepreneurial intentions of youth: The role of access to finance. Engineering Economics, 33(1), 86–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, S. C., Costa, S. F., Neumeyer, X., & Caetano, A. (2016). Bridging entrepreneurial cognition research and entrepreneurship education: What and how. In Annals of entrepreneurship education and pedagogy—2016 (pp. 83–108). Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, S. C., Neumeyer, X., & Morris, M. H. (2019). Entrepreneurship education in a poverty context: An empowerment perspective. Journal of Small Business Management, 57(1), 6–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saptono, A., Wibowo, A., Widyastuti, U., Narmaditya, B. S., & Yanto, H. (2021). Entrepreneurial self-efficacy among elementary students: The role of entrepreneurship education. Heliyon, 7(9), e07995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapero, A., & Sokol, L. (2002). Some social dimensions of entrepreneurship. In Entrepreneurship: Critical perspectives on business and management (Vol. 4, pp. 83–111). Routledge. (Original work published 1982). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherkat, A., & Chenari, A. (2022). Assessing the effectiveness of entrepreneurship education in the universities of Tehran province based on an entrepreneurial intention model. Studies in Higher Education, 47(1), 97–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirokova, G., Osiyevskyy, O., & Bogatyreva, K. (2016). Exploring the intention–behavior link in student entrepreneurship: Moderating effects of individual and environmental characteristics. European Management Journal, 34(4), 386–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, C., & Schell, M. S. (2009). Managing across cultures: The 7 keys to doing business with a global mindset. McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Soria-Barreto, K., Honores-Marin, G., Gutiérrez-Zepeda, P., & Gutiérrez-Rodríguez, J. (2017). Prior exposure and educational environment towards entrepreneurial intention. Journal of Technology Management & Innovation, 12(2), 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souitaris, V., Zerbinati, S., & Al-Laham, A. (2007). Do entrepreneurship programmes raise entrepreneurial intention of science and engineering students? The effect of learning, inspiration and resources. Journal of Business Venturing, 22(4), 566–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, U., Uhlaner, L. M., & Stride, C. (2015). Institutions and social entrepreneurship: The role of institutional voids, institutional support, and institutional configurations. Journal of International Business Studies, 46(3), 308–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, D. M., & Meek, W. R. (2012). Gender and entrepreneurship: A review and process model. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 27(5), 428–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C. S., Lau, X. S., Kung, Y. T., & Kailsan, R. A. L. (2019). Openness to experience enhances creativity: The mediating role of intrinsic motivation and the creative process engagement. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 53(1), 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, E. R. (2009). Individual entrepreneurial intent: Construct clarification and development of an internationally reliable metric. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(3), 669–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, J. S., Elliott, M. N., & Klein, D. J. (2006). Social control of health behavior: Associations with conscientiousness and neuroticism. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32(9), 1143–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turgunpulatovich, A. O. (2022). Formation of financing technology and communication relations in increasing the competitiveness of small business entities. International Journal of Social Science & Interdisciplinary Research, 11(1), 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- van Ewijk, A. R., Cheng, J., & Chang, F. Y. (2023). Why is changing students’ entrepreneurial intentions so hard? On dissonance reduction and the self-imposed self-fulfilling prophecy. The International Journal of Management Education, 21(3), 100896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verheul, I., Thurik, R., Grilo, I., & Van der Zwan, P. (2012). Explaining preferences and actual involvement in self-employment: Gender and the entrepreneurial personality. Journal of Economic Psychology, 33(2), 325–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. H., You, X., Wang, H. P., Wang, B., Lai, W. Y., & Su, N. (2023). The effect of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intention: Mediation of entrepreneurial self-efficacy and moderating model of psychological capital. Sustainability, 15(3), 2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiklund, J., Nikolaev, B., Shir, N., Foo, M. D., & Bradley, S. (2019). Entrepreneurship and well-being: Past, present, and future. Journal of Business Venturing, 34(4), 579–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulou, P., & Sahinidis, A. (2022). Shaping entrepreneurial intentions: The moderating role of entrepreneurship education. Balkan & Near Eastern Journal of Social Sciences (BNEJSS), 8, 116–121. [Google Scholar]

- Xanthopoulou, P., & Sahinidis, A. (2025). Exploring the impact of entrepreneurship education on social entrepreneurial intentions: A diary study of tourism students. Administrative Sciences, 15(3), 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulou, P., Sahinidis, A., & Paganou, S. (2024, September). Inside the Entrepreneurial Mind: A Diary Research on the Evolution of Students’ Entrepreneurial Intentions. In European Conference on Innovation and Entrepreneurship (pp. 845–852). Academic Conferences International Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Yukongdi, V., & Lopa, N. Z. (2017). Entrepreneurial intention: A study of individual, situational and gender differences. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 24(2), 333–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zampetakis, L. A., Kafetsios, K., Bouranta, N., Dewett, T., & Moustakis, V. S. (2009). On the relationship between emotional intelligence and entrepreneurial attitudes and intentions. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour & Research, 15(6), 595–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H., Seibert, S. E., & Hills, G. E. (2005). The mediating role of self-efficacy in the development of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(6), 1265–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zisser, M. R., Johnson, S. L., Freeman, M. A., & Staudenmaier, P. J. (2019). The relationship between entrepreneurial intent, gender and personality. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 34(8), 665–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Measure | Before (Pre) | After (Post) | Between-Group Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Size | 114 | 114 | — |

| Mean (SD) | 4.419 (1.751) | 4.632 (1.549) | Mean Difference (95% CI): −0.213 (−0.344 to −0.082) |

| Shapiro–Wilk | W = 0.982 (p = 0.115) | — | |

| Kolmogorov–Smirnov | KS = 0.088 (p = 0.324) | — | |

| t-Test | — | — | t = −3.222, p = 0.002 |

| Wilcoxon test | — | — | W = 1339, p = 0.014 |

| Cohen’s d | — | — | d = 0.302 |

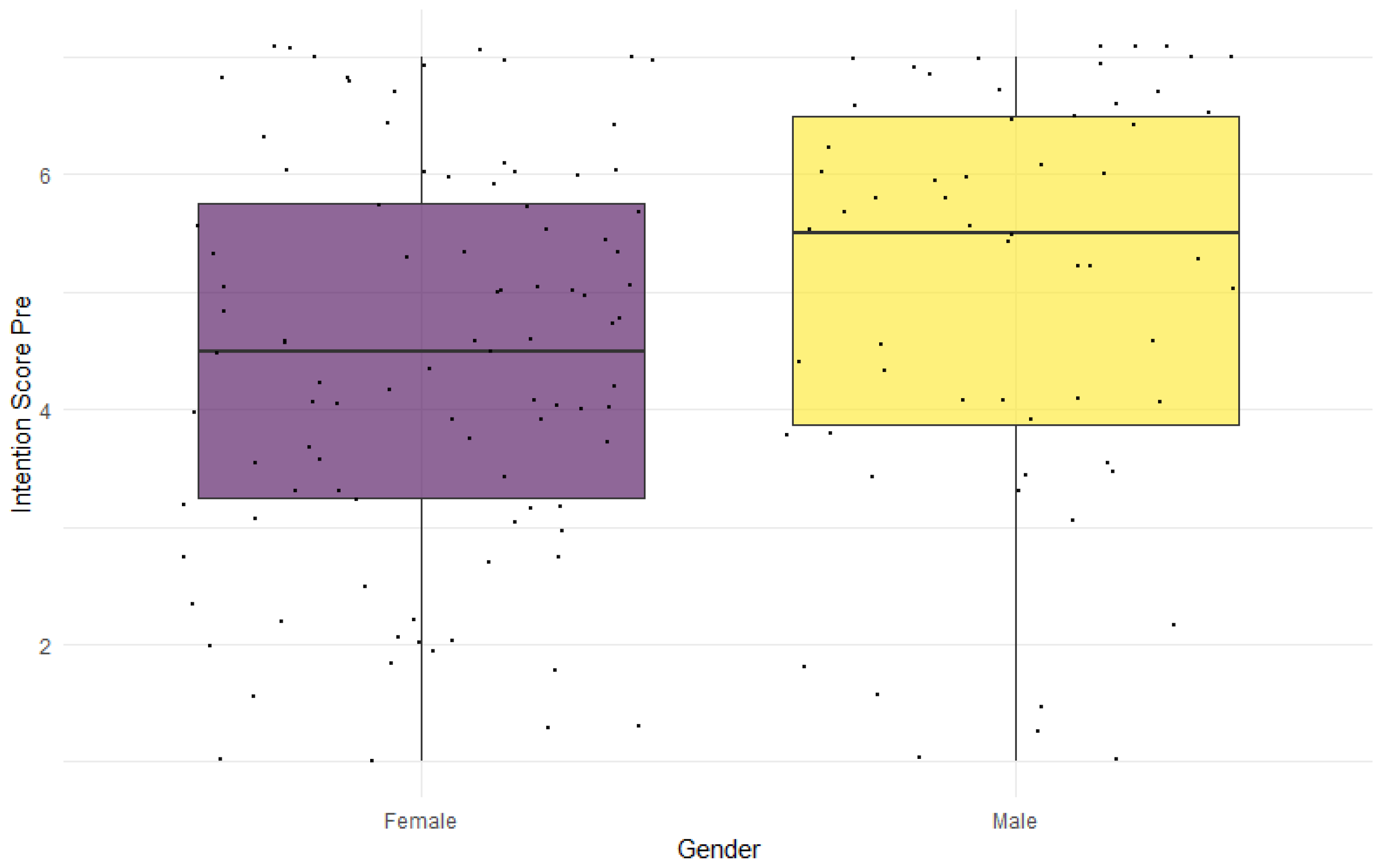

| Measure | Male | Female | Between-Group Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Size | 59 | 96 | — |

| Mean (SD) | 4.987 (1.773) | 4.391 (1.663) | Mean Difference (95% CI): 0.597 (0.029 to 1.164) |

| Shapiro–Wilk | W = 0.964 (p = 0.081) | W = 0.979 (p = 0.127) | — |

| Kolmogorov–Smirnov | KS = 0.139 (p = 0.203) | KS = 0.073 (p = 0.686) | — |

| t-Test | — | — | t = 2.083, p = 0.039 |

| Mann–Whitney U | — | — | U = 344, p = 0.024 |

| Cohen’s d | — | — | d = 0.347 |

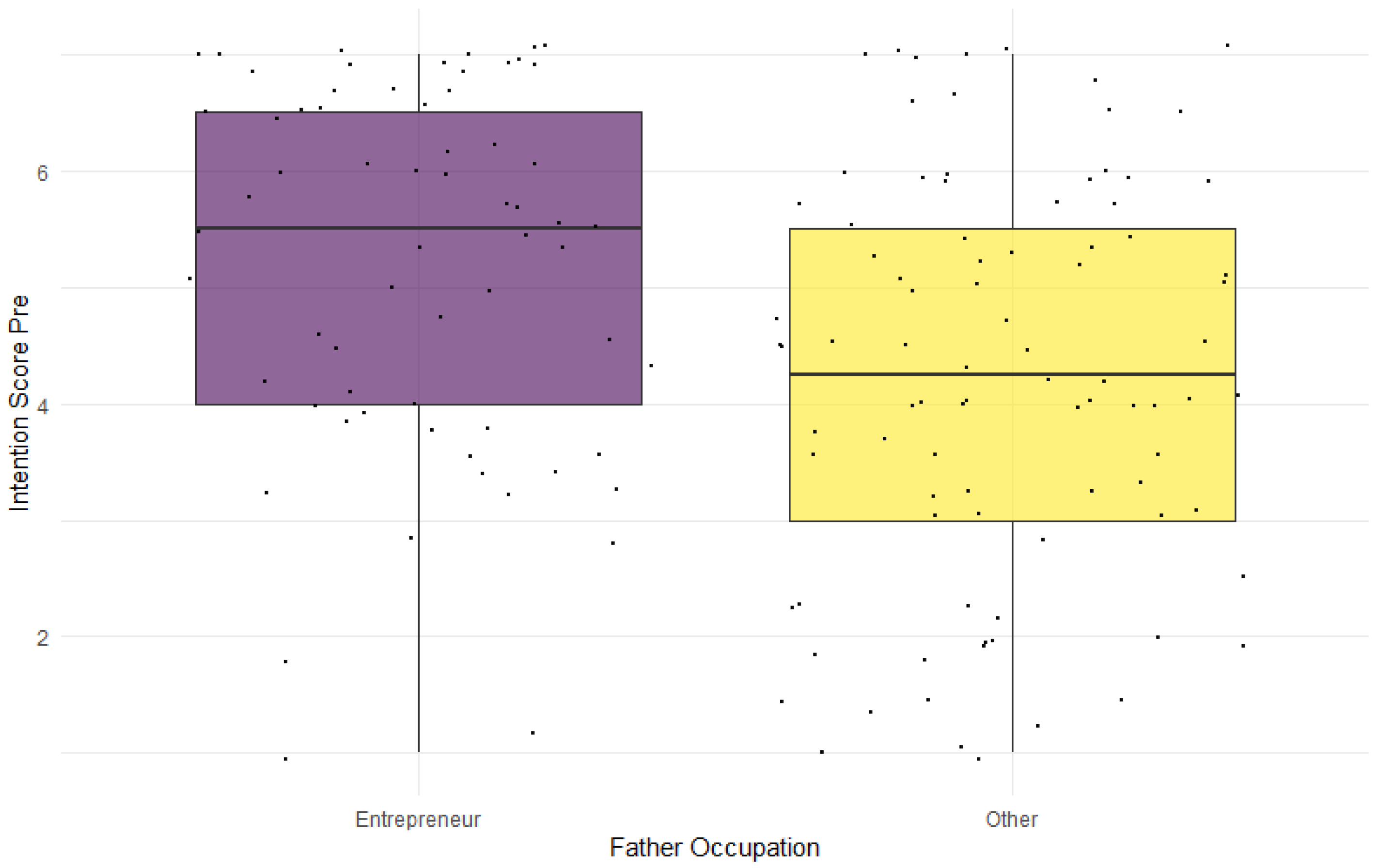

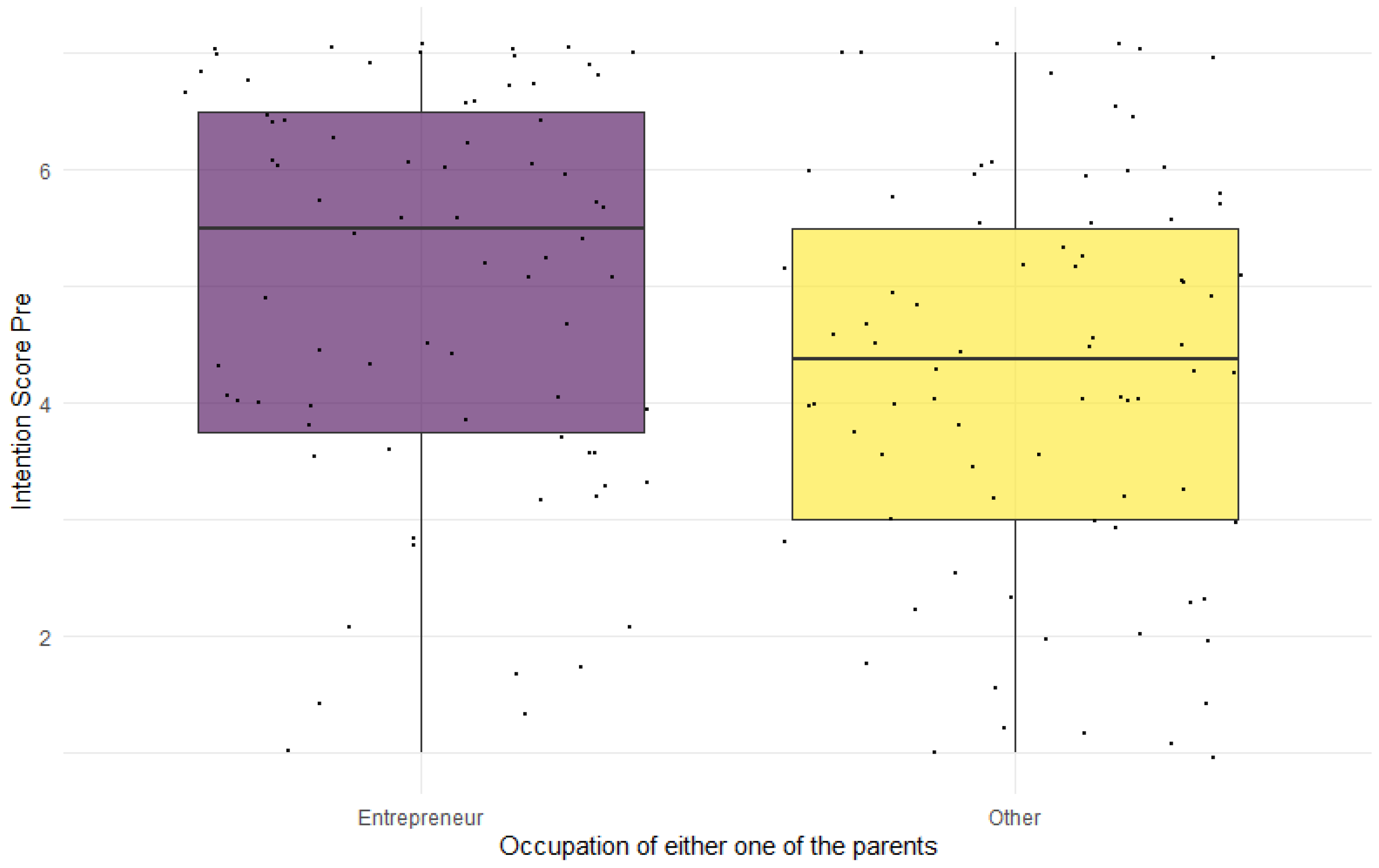

| Measure | Entrepreneur | Other | Between-Group Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Size | 65 | 90 | — |

| Mean (SD) | 5.196 (1.574) | 4.200 (1.716) | Mean Difference (95% CI): 0.996 (0.470 to 1.522) |

| Shapiro–Wilk | W = 0.969 (p = 0.102) | W = 0.977 (p = 0.120) | — |

| Kolmogorov–Smirnov | KS = 0.126 (p = 0.254) | KS = 0.083 (p = 0.561) | — |

| t-Test | — | — | t = 3.743, p < 0.001 |

| Mann–Whitney U | — | — | U = 3888, p < 0.001 |

| Cohen’s d | — | — | d = 0.605 |

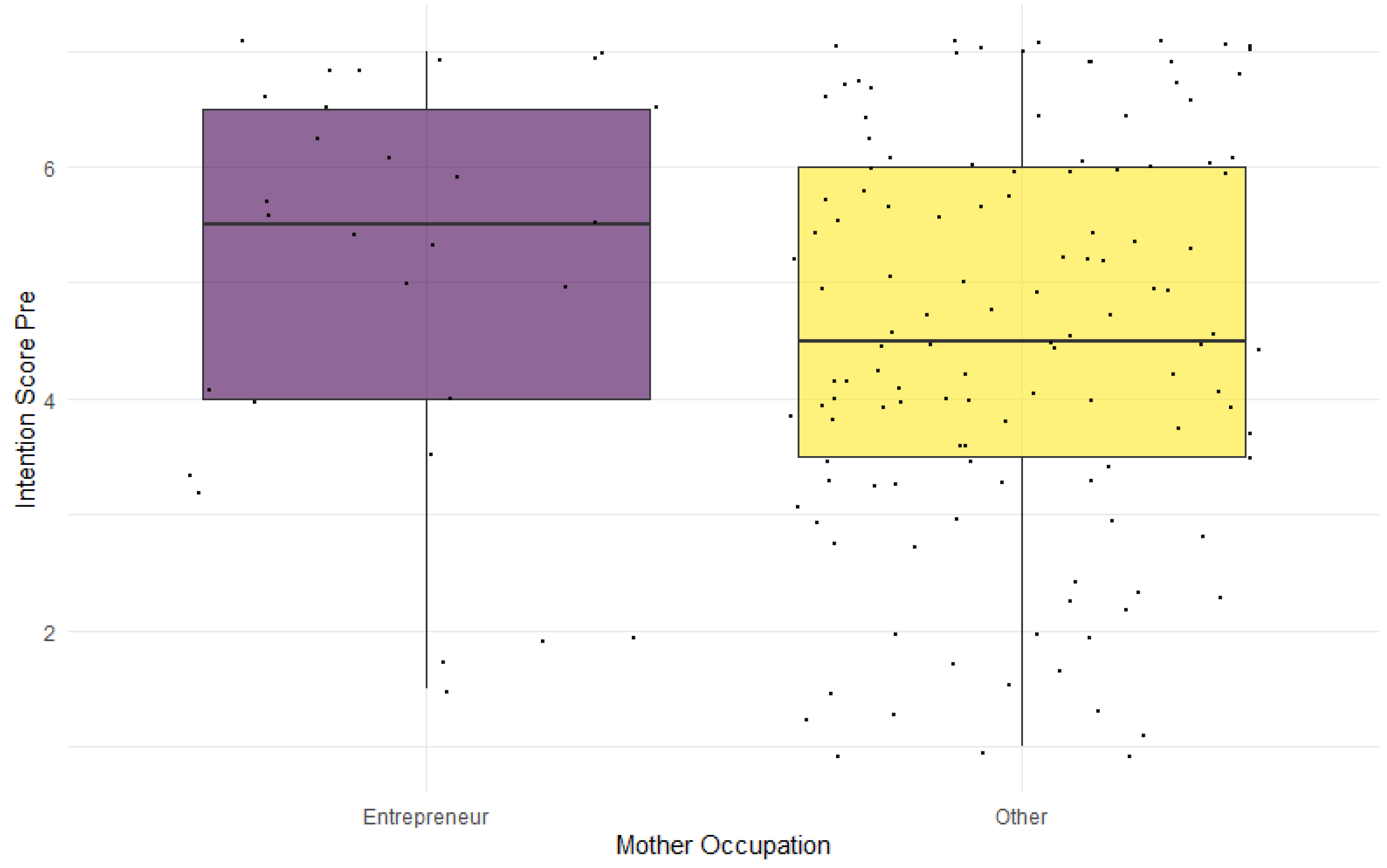

| Measure | Entrepreneur | Other | Between-Group Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Size | 29 | 126 | — |

| Mean (SD) | 5.034 (1.752) | 4.521 (1.711) | Mean Difference (95% CI): 0.513 (−0.213 to 1.238) |

| Shapiro–Wilk | W = 0.939 (p = 0.096) | W = 0.982 (p = 0.083) | — |

| Kolmogorov–Smirnov | KS = 0.156 (p = 0. 477) | KS = 0.084 (p = 0.337) | — |

| t-Test | — | — | t = 1.427, p = 0.161 |

| Mann–Whitney U | — | — | U = 2153, p = 0.135 |

| Cohen’s d | — | — | d = 0.296 |

| Measure | Entrepreneur | Other | Between-Group Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Size | 19 | 136 | — |

| Mean (SD) | 5.697 (1.168) | 4.467 (1.739) | Mean Difference (95% CI): 1.230 (0.604 to 1.856) |

| Shapiro–Wilk | W = 0.920 (p = 0.111) | W = 0.983 (p = 0.096) | — |

| Kolmogorov–Smirnov | KS = 0.132 (p = 0.893) | KS = 0.090 (p = 0.216) | — |

| t-Test | — | — | t = 4.012, p < 0.001 |

| Mann–Whitney U | — | — | U = 1820.5, p = 0.004 |

| Cohen’s d | — | — | d = 0.831 |

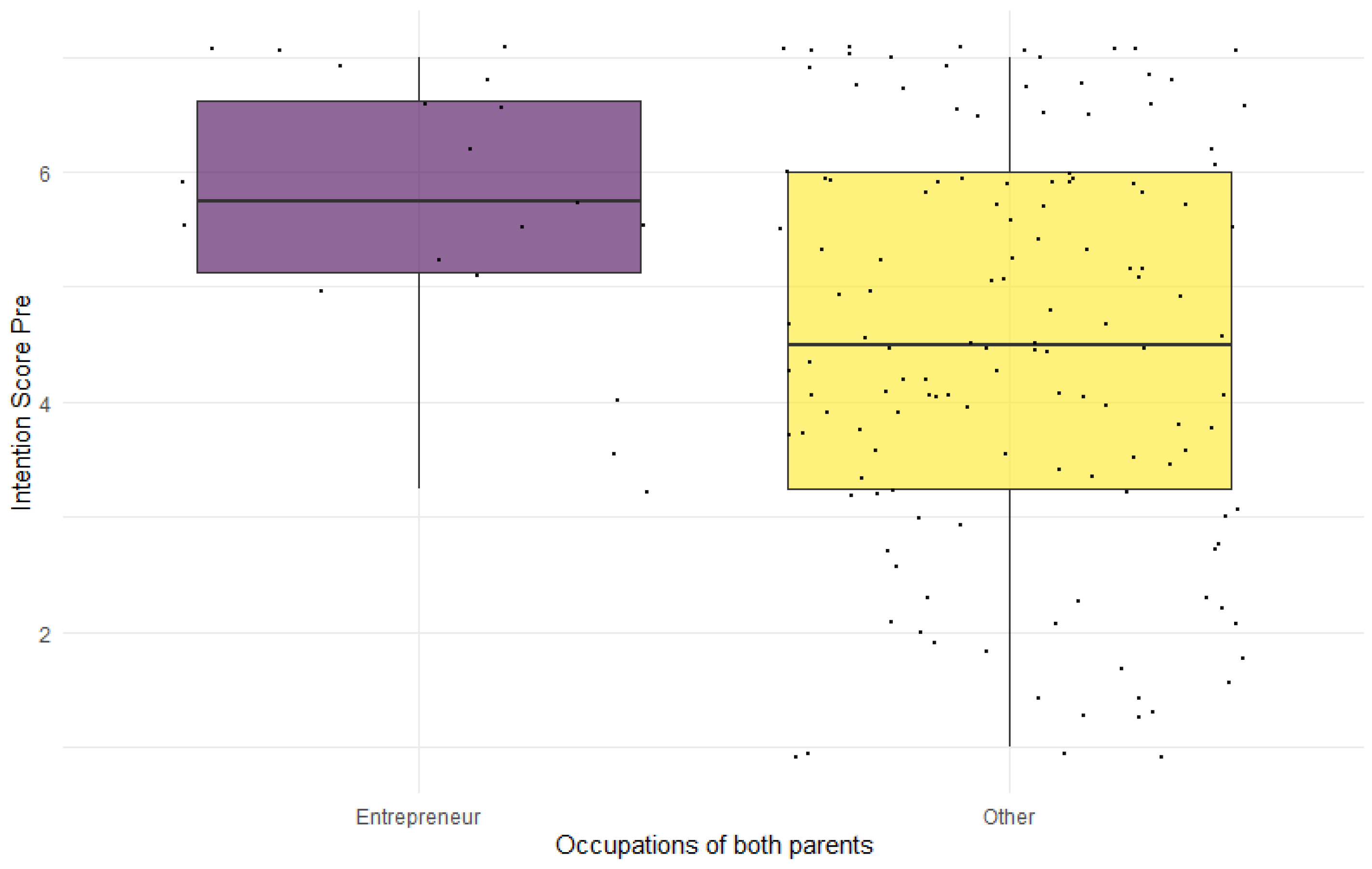

| Measure | Entrepreneur | Other | Between-Group Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Size | 75 | 80 | — |

| Mean (SD) | 5.007 (1.698) | 4.253 (1.679) | Mean Difference (95% CI): 0.754 (0.217 to 1.290) |

| Shapiro–Wilk | W = 0.973 (p = 0.103) | W = 0.974 (p = 0.097) | — |

| Kolmogorov–Smirnov | KS = 0.134 (p = 0.135) | KS = 0.078 (p = 0.721) | — |

| t-Test | — | — | t = 2.776, p = 0.006 |

| Mann–Whitney U | — | — | U = 3760.5, p = 0.006 |

| Cohen’s d | — | — | d = 0.447 |

| Variable | Estimate | Std. Error | t Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | −2.09450 | 1.86709 | −1.122 | 0.2638 |

| Gender: Female | −0.41368 | 0.28160 | −1.469 | 0.1440 |

| Age: 26 to 34 | 1.06675 | 0.93583 | 1.140 | 0.2562 |

| Level of education: Post-secondary graduate | 3.44185 | 2.12192 | 1.622 | 0.1070 |

| Level of education: Master’s degree holder | 3.44613 | 2.16249 | 1.594 | 0.1132 |

| Level of education: Student | 2.54976 | 1.47638 | 1.727 | 0.0863 |

| Openness to experience | 0.39711 | 0.17064 | 2.327 | 0.0214 |

| Conscientiousness | −0.01466 | 0.20155 | −0.073 | 0.9421 |

| Extraversion | 0.56170 | 0.15772 | 3.561 | 0.0005 |

| Agreeableness | −0.03614 | 0.19792 | −0.183 | 0.8554 |

| Neuroticism | −0.06799 | 0.12445 | −0.546 | 0.5857 |

| Step | Df | Deviance Resid. | Df | Resid. Dev | AIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 144 | 349.9167 | 148.2118 | |||

| Education Level | 3 | 8.98770124 | 147 | 358.9044 | 146.1428 |

| Agreeableness | 1 | 0.00227925 | 148 | 358.9066 | 144.1438 |

| Age | 1 | 0.00427847 | 149 | 358.9109 | 142.1456 |

| Conscientiousness | 1 | 0.03927795 | 150 | 358.9502 | 140.1626 |

| Neuroticism | 1 | 0.58996115 | 151 | 359.5402 | 138.4171 |

| Variable | Estimate | Std. Error | t Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 0.01561 | 0.85917 | 0.018 | 0.985524 |

| Gender: Female | −0.45924 | 0.25631 | −1.792 | 0.075180 |

| Openness to experience | 0.41672 | 0.15538 | 2.682 | 0.008135 |

| Extraversion | 0.52257 | 0.14955 | 3.494 | 0.000624 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Xanthopoulou, P.; Sahinidis, A.; Vassiliou, E.E.; Kavoura, A. When Intentions Stall: Exploring the Quasi-Longitudinal Divide Between Entrepreneurial Intention and Action. Adm. Sci. 2026, 16, 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci16010014

Xanthopoulou P, Sahinidis A, Vassiliou EE, Kavoura A. When Intentions Stall: Exploring the Quasi-Longitudinal Divide Between Entrepreneurial Intention and Action. Administrative Sciences. 2026; 16(1):14. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci16010014

Chicago/Turabian StyleXanthopoulou, Panagiota, Alexandros Sahinidis, Evangelos E. Vassiliou, and Androniki Kavoura. 2026. "When Intentions Stall: Exploring the Quasi-Longitudinal Divide Between Entrepreneurial Intention and Action" Administrative Sciences 16, no. 1: 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci16010014

APA StyleXanthopoulou, P., Sahinidis, A., Vassiliou, E. E., & Kavoura, A. (2026). When Intentions Stall: Exploring the Quasi-Longitudinal Divide Between Entrepreneurial Intention and Action. Administrative Sciences, 16(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci16010014