A Decision-Making Framework for Public–Private Partnership Model Selection in the Space Sector: Policy and Market Dynamics Across Countries

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Space PPP Typology

2.2. Policy Environment Indicators

2.2.1. National Strategic Goals (P1)

- Leadership and national security prioritize sovereignty, defense capabilities, and technological supremacy, typical of established space powers with codified space doctrines and long-standing military–industrial space infrastructures.

- Economic growth and national security frame space as a catalyst for industrial growth, technological diffusion, and employment, common in emerging space systems pursuing liberalization.

- National security, scientific advancement, and market expansion emphasize research, innovation, and gradual commercial integration, common among technologically advanced yet institutionally conservative space actors.

- Strategic diversification and national prestige use space initiatives for international visibility, soft power projection, and symbolic capital and is often found in nascent space programs seeking global legitimacy or recognition.

2.2.2. Government Role Preference (P2)

- Principal role: The government retains centralized control, retaining exclusive authority over financing, design, ownership, and operational control. In the principal model, the government utilizes PPPs primarily as conventional procurement mechanisms, defining project scope, establishing performance metrics, and overseeing implementation to safeguard public interests and maximize societal benefits (Zancan et al., 2024). The private sector performs the role of a contractor, executing tasks based on predetermined public-sector specifications (Olusola Babatunde et al., 2012).

- Partner role: The government engages more interactively in an integrative approach with the private sector, engaging in co-financing arrangements, joint ventures, and decision-making within collaborative structures, while strategic oversight remains public, and elements of risk and ownership are distributed across sectors. This model involves shared risk, resources, and strategic planning between public and private entities (Brinkerhoff, 2002; Newman, 2022).

- Enabler role: The government acts as a facilitator, establishing enabling regulatory and institutional frameworks that support private-sector innovation and leadership. This approach minimizes direct state involvement and emphasizes deregulation and privatization, allowing private actors to initiate and implement projects while the public sector provides oversight and policy support (Alan Lindenmoyer, 2014; Stone et al., 2008). This model reflects a market-led innovation strategy.

2.2.3. Regulatory Structure (P3)

- Restrictive: Characterized by stringent licensing processes, bureaucratic hurdles, and limited and selective private-sector involvement, this framework often acts as a deterrent to potential PPP ventures in the space domain (Howlett, 2023). This environment exhibits a high degree of governmental control, potentially stifling innovation and hindering the agility required for successful commercial space operations (Baumann et al., 2018).

- Structured and predictable: This category signifies a more mature regulatory framework, offering clear guidelines and legal frameworks, transparent processes for private-sector entry, and established legal precedents for space activities, thereby fostering investor confidence and encouraging long-term commitments to PPP projects (Hofmann & Blount, 2018).

- Flexible: This category represents regulatory environments that prioritize adaptability and responsiveness to the rapidly evolving space sector. It emphasizes streamlined approval processes, accommodates novel technologies and business models by using adaptive tools such as regulatory sandboxes, and prioritizes innovation responsiveness (Allan Lindenmoyer, 2006).

2.3. Market Environment Indicators

2.3.1. Capital Access (M1)

- High accessibility: liquid capital markets, mature venture capital ecosystems, and active private-equity participation in PPPs.

- Moderate accessibility: financing is led by public or quasi-public institutions through grants, development funds, or sovereign vehicles, while private capital plays a supplementary role.

- Low accessibility: Funding is dominated by state budgets, with private investment minimal or structurally constrained. PPPs almost entirely depend on public financing.

2.3.2. Private-Sector Capability (M2)

- High capability: private firms can design, develop, launch, and operate space systems with autonomy in both upstream and downstream space markets.

- Moderate capability: private firms are active and may possess technical competencies but remain dependent on government contracts or foreign partnerships, a common emerging commercial ecosystem under state guidance.

- Low capability: Few private firms operate independently in the space sector. These ecosystems often rely on foreign prime contractors or international partnerships for mission execution, which is common in nascent space countries.

2.3.3. Commercial Demand (M3)

- High demand: Robust and diversified domestic and international markets exist, and private firms compete for contracts.

- Moderate demand: Commercial interest is emerging, but the market remains largely shaped by public procurement or state-led initiatives.

- Low demand: Domestic commercial demand is minimal or underdeveloped. The market is driven almost entirely by government procurement, and commercial buyers are scarce.

3. Methods and Data

3.1. Methodology

3.2. Case Selection and Theoretical Sampling

3.3. Data Collection

4. Results

4.1. Within-Case Analysis

4.1.1. United States Within-Case Analysis Findings

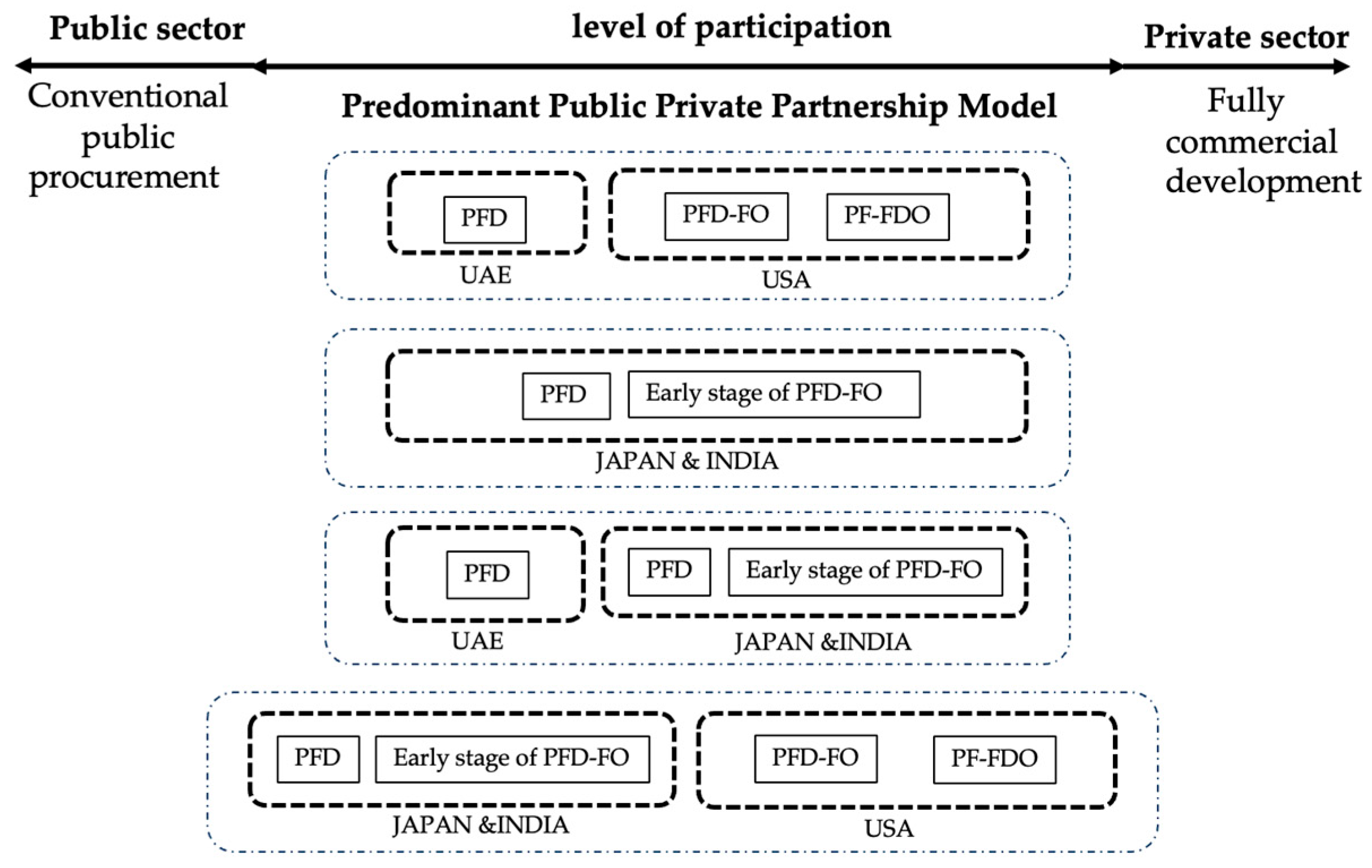

4.1.2. Predominant PPP Models in the United States: PF-FDO and PFD-FO

4.1.3. Japan Within-Case Analysis Findings

4.1.4. Predominant PPP Models in Japan: PFD, Early-Stage PFD-FO

4.1.5. India Within-Case Analysis Findings

4.1.6. Predominant PPP Models in India: PFD and Early-Stage PFD-FO

4.1.7. United Arab Emirates Within-Case Analysis Findings

4.1.8. Predominant PPP Models in the UAE: PFD

4.2. Cross-Case Analyses

- USA–UAE: This comparison contrasts a fully aligned PPP ecosystem (U.S.) with a structurally constrained one (UAE). Both pursue ambitious space strategies but diverge in purpose: the U.S. emphasizes strategic leadership (P1), while the UAE focuses on prestige and symbolic advancement. The U.S. combines enabling governance (P2), flexible regulation (P3), and high market readiness (M1–M3), supporting full delegation through PF-FDO and PFD-FO models. In contrast, the UAE exhibits principal-led governance, discretionary regulation, and low private capability, capital access, and commercial demand. These structural limitations—not just policy intent—constrain PPPs to basic PFD forms, where private actors serve as vendors within state-owned systems. High-autonomy PPPs require both institutional willingness and market enablers. Where either is absent, especially in all three market environment indicators, delegation becomes structurally impossible, not merely politically undesirable.

- Japan–India: This comparison examines two emerging space powers that, despite distinct institutional trajectories, converge on similar PPP typologies of PFD and early-stage PFD-FO models shaped under moderate capital access (M1) and private-sector capability (M2). Divergent governance structures can yield structurally similar outcomes when filtered through differing institutional constraints. Japan maintains a principal-led approach emphasizing control and mission assurance, while India adopts a partner-style posture, aiming to crowd in private actors through regulatory reform. Both exhibit moderate M1 and M2, but Japan’s restrictive regulation (P3) and hierarchical coordination limit delegation. The key differentiator is commercial demand (M3). India’s is moderately diversifying through defense payloads and hybrid satellite services, whereas Japan remains supply-driven, with weak private contracting and minimal demand-side dynamism. The absence of PF-FDO models in both countries underscores that PPP advancement requires more than technical capacity or funding. It hinges on the co-evolution of regulatory devolution, market liberalization, and demand diversification. While India moves toward autonomy, Japan’s governance logic reinforces centralization and institutional path dependence. PPP outcomes are shaped not only by market indicators but by how those indicators interact with governance intent and institutional design.

- UAE–Japan: Both Japan and the UAE feature principal-led governance, restrictive regulatory regimes (P3), low commercial demand (M3), and public-sector-dominated funding structures (M1), offering a critical test of the emerging construction of systemic alignment. Despite their shared constraints, PPP outcomes diverge. Japan supports early-stage PFD-FO models, particularly in analytics and subsystem integration, while the UAE remains confined to low-autonomy PFD configurations. This asymmetry is explained by differences in private-sector capability (M2), capital access (M1), and strategic intent (P1). Private-sector capability (M2) and capital access (M1) are critical preconditions for PPP advancement, particularly in centralized, regulation-heavy systems. Japan’s moderate M1 and M2 levels enable limited evolution despite rigid institutions, the UAE’s low levels in both dimensions result in structural stasis. Under a principal-led governance model with restrictive regulation, it is the strength of market environment indicators, not policy reform alone, that enables PPPs to move toward higher autonomy.

- UAE–India: This comparison explores how institutional reform rather than market maturity alone can enable PPP progression. Both India and the UAE maintain centralized, mission-driven governance, but they diverge in regulatory and strategic orientation: the UAE operates a principal-led model with discretionary restrictive regulation, while India follows a partner-style framework underpinned by structured and predictable regulation and reform. As a result, PPP outcomes differ. The UAE remains confined to low-autonomy PFD models dominated by public funding and operations. India has advanced to early PFD-FO models in downstream services, allowing limited private ownership under state-defined conditions. Strategically (P1), India’s dual goals of economic growth and security incentivize capability devolution, while the UAE’s prestige-driven posture limits private enablement. This comparison highlights that PPP evolution in centralized systems depends not just on regulatory reform but on capital diversification, private capability, and strategic intent. India demonstrates that structured reform can enable upward PPP mobility; the UAE illustrates the limits of symbolic liberalization without systemic enablers.

- India–USA: This comparison illustrates how institutional logics and market structures condition PPP autonomy. Both countries support commercial participation but diverge in how far delegation proceeds. The U.S. operates an enabling government role system (P2) with flexible regulation (P3), a robust market environment, and private operation and ownership in PF-FDO and PFD-FO models. India shows transitional dynamics: structured regulation, moderate market indicators, and emerging markets enable early PFD-FO models, especially in downstream domains. However, upstream projects remain publicly controlled. The contrast illustrates that structural asymmetries, not just policy vision, explain model divergence. The U.S. framework is aligned across all indicators; India’s capacity-building is partial. This case suggests that policy reform must coincide with capital depth, industrial autonomy, and institutional readiness to enable full-cycle delegation. Policy reform must coincide with strong market environment conditions: specifically, high levels of capital access, private-sector capability, and commercial demand, as well as enabling and flexible governance structures to support higher autonomy PPP models.

- Japan–USA: The juxtaposition of Japan and the United States reveals how structurally divergent space governance systems produce distinct public–private partnership (PPP) outcomes. The U.S. system embodies a delegative logic, in which the state retains strategic oversight but intentionally decentralizes operational authority to private firms. Japan, by contrast, is governed by a stewardship logic in which the state preserves centralized control not only to safeguard national objectives but to manage systemic interdependencies. Government agencies prioritize mission integrity over market autonomy, producing PPPs that favor institutional certainty over flexibility. These contrasting approaches demonstrate that PPP evolution is not only a function of resource levels or regulatory thresholds but of how national innovation systems assign authority, structure accountability, and internalize uncertainty. This distinction explains why PPPs in Japan, despite moderate capital access, remain bounded within state-defined performance corridors.

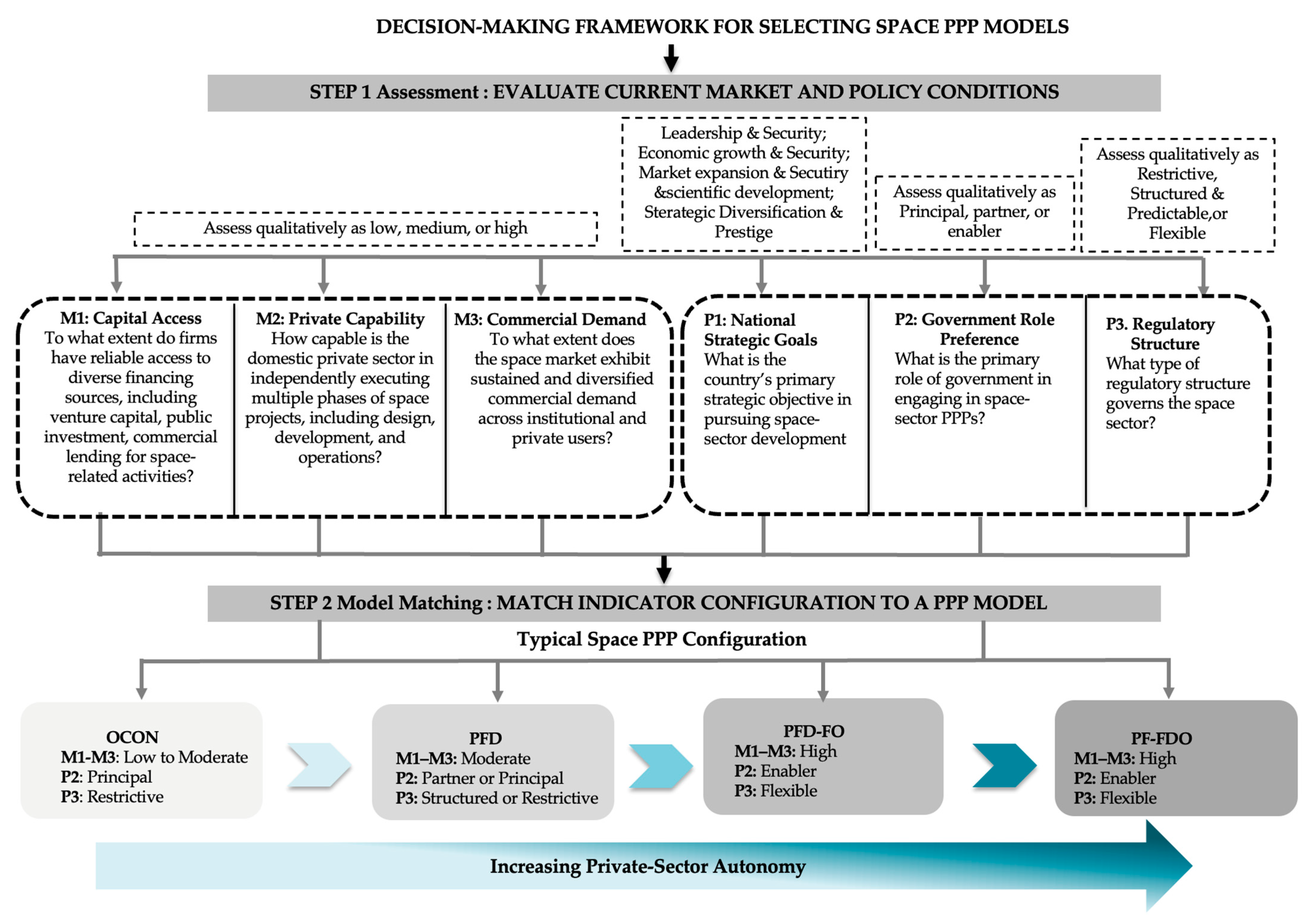

4.3. Decision-Making Framework for Selecting PPP Models

- Step 1: Assessment of Current Market and Policy Conditions

- Step 2: Model Matching Based on Indicator Configuration

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- AIRBUS. (2024). Airbus delivers Space42’s thuraya 4 satellite to launch site. Available online: https://www.airbus.com/en/newsroom/news/2024-12-airbus-delivers-space42s-thuraya-4-satellite-to-launch-site (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- Akintoye, A., Beck, M., & Kumaraswamy, M. (2015). An overview of public private partnerships. In Public private partnerships. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Al Harmi, M. A. (2016, May 16–20). MBRSC mission operations. 14th International Conference on Space Operations, Daejeon, Republic of Korea. [Google Scholar]

- Aliberti, M. (2018). India in space: Between utility and geopolitics. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Al Jawali, H., Darwish, T. K., Scullion, H., & Haak-Saheem, W. (2022). Talent management in the public sector: Empirical evidence from the Emerging Economy of Dubai. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 33(11), 2256–2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Rashedi, N., Al Shamsi, F., & Al Hosani, H. (2020). UAE approach to space and security. In Handbook of space security: Policies, applications and programs (pp. 621–652). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Al Tair, H. (2017). Securing UAE’s independent space industry: Building, launching, operating [Master’s thesis, Khalifa University]. [Google Scholar]

- Alzaabi, M., Burtz, L.-J., Amilineni, S., Almesmar, S., Khoory, M. S., Albalooshi, M., Salem, A., Almaeeni, S., Els, S. G., & Almarzooqi, H. (2024). Operational concepts and rehearsal results of the first emirates lunar rover: Rashid-1. Space Science Reviews, 220(8), 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, H., Brain, D., Sharaf, O., Withnell, P., McGrath, M., Alloghani, M., Al Awadhi, M., Al Dhafri, S., Al Hamadi, O., & Al Matroushi, H. (2022). The emirates mars mission. Space Science Reviews, 218(1), 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antwi-Boateng, O., & Alhashmi, A. A. (2022). The emergence of the United Arab Emirates as a global soft power: Current strategies and future challenges. Economic and Political Studies, 10(2), 208–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki, S. (2008). Introduction to the Japanese basic space law of 2008. Zeitschrift für Luft-und Weltraumrecht, 57(4), 585–589. [Google Scholar]

- Aoki, S. (2009). Current status and recent developments in Japan’s national space law and its relevance to Pacific rim space law and activities. Journal of Space Law, 35, 363. [Google Scholar]

- Araki, T., Kotake, H., Saito, Y., Tsuji, H., Toyoshima, M., Makino, K., Koga, M., & Sato, N. (2022, March 28–31). Recent R&D activities of the lunar–the earth optical communication systems in Japan. 2022 IEEE International Conference on Space Optical Systems and Applications (ICSOS), Kyoto City, Japan. [Google Scholar]

- Autry, G. (2018). Commercial orbital transportation services: A case study for national industrial policy. New Space, 6(3), 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelspace. (2021). Axelspace and synspective to demonstrate one-stop service of small satellite constellation under support of the government of Japan. Available online: https://www.axelspace.com/news/press_20220114/ (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Babatunde, S. O., & Perera, S. (2017). Analysis of financial close delay in PPP infrastructure projects in developing countries. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 24(6), 1690–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, R., Cave, M., & Lodge, M. (2011). Understanding regulation: Theory, strategy, and practice. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baluragi, H., & Suresh, B. N. (2020). Indian space program: Evolution, dimensions, and initiatives. In Handbook of space security: Policies, applications and programs (pp. 1421–1439). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Batley, R., Larbi, G. A., Larbi, G., & Larbi, G. (2004). Changing role of government. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Batra, R. (2021). A thematic analysis to identify barriers, gaps, and challenges for the implementation of public-private partnerships in housing. Habitat International, 118, 102454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, I., El Bajjati, H., & Pellander, E. (2018). NewSpace: A wave of private investment in commercial space activities and potential issues under international investment law. The Journal of World Investment & Trade, 19(5–6), 930–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, T., Levine, R., & Loayza, N. (2000). Finance and the sources of growth. Journal of Financial Economics, 58(1), 261–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertran, X., & Vidal, A. (2021). The Implementation of a public-private partnership for galileo: Comparison of Galileo and Skynet 5 with other projects. Online Journal of Space Communication, 5(9), 7. [Google Scholar]

- Bhalodia, D. (2024). New space revolution: Prospective launchers for small satellites, challenges for the micro launch industry and its implications for SmallSat manufacturers [Master thesis, TU Delft]. [Google Scholar]

- Boardman, A. E., Greve, C., & Hodge, G. A. (2015). Comparative analyses of infrastructure public-private partnerships (Vol. 17, pp. 441–447). Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan, K. (2015). Beyond technocentrism. Constructivist Foundations, 10(3), 289–296. [Google Scholar]

- Brinkerhoff, J. M. (2002). Government–nonprofit partnership: A defining framework. Public Administration and Development: The International Journal of Management Research and Practice, 22(1), 19–30. [Google Scholar]

- BryceTech. (2023). Start-up space 2023. Available online: https://brycetech.com/reports/report-documents/Bryce_Start_Up_Space_2023.pdf (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Bult-Spiering, M., & Dewulf, G. (2008). Strategic issues in public-private partnerships: An international perspective. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- CAO. (2016). Act on launching spacecraft and launch vehicle and control of spacecraft. Cabinet Office, Government of Japan. Available online: https://www8.cao.go.jp/space/english/activity/documents/space_activity_act.pdf (accessed on 19 March 2024).

- CAO. (2017a). Regulations for enforcement of the act on launching spacecraft and launch vehicle and control of spacecraft. Cabinet Office, Government of Japan. Available online: https://www8.cao.go.jp/space/english/activity/documents/space_activity_regulation.pdf (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- CAO. (2017b). Review standards and standard period of time for process relating to procedures under the act on launching of spacecraft, etc. and control of spacecraft. Cabinet Office, Government of Japan. Available online: https://www8.cao.go.jp/space/english/activity/documents/reviewstand.pdf (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- CAO. (2017c). Space industry vision 2030. Space Policy Committee. Available online: https://www8.cao.go.jp/space/vision/vision.html (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- CAO. (2020). Outline of the basic plan on space policy. Available online: https://www8.cao.go.jp/space/english/basicplan/2020/abstract_0825.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- CAO. (2023). Space security initiative. Available online: https://www8.cao.go.jp/space/anpo/kaitei_fy05/enganpo_fy05.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- CAO. (2025). Japan’s space policy overview. Available online: https://www8.cao.go.jp/space/kikin/kihonhousin_20250326.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Carbonara, N., & Pellegrino, R. (2020). The role of public private partnerships in fostering innovation. Construction Management and Economics, 38(2), 140–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelblanco, G., Marco, A. D., & Casady, C. B. (2025). A system dynamics approach to concession period optimization in public-private partnerships (PPPs). Public Works Management & Policy, 30(3), 292–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitra, B., & Shet, A. (2024). Space law and intellectual property rights: Issues and challenges. Shodhshauryam, International Scientific Refereed Research Journal, 7(4), 23–36. [Google Scholar]

- Coglianese, C. (2012). Measuring regulatory performance. Evaluating the impact of regulation and regulatory policy. Expert paper, 1. OECD. [Google Scholar]

- Cottom, T. S. (2022). A review of indian space launch capabilities. New Space, 10(1), 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CRS. (2025). Regulation of commercial human spaceflight safety: Overview and issues for congress. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R48050 (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Darko, D., Zhu, D., Quayson, M., Hossin, M. A., Omoruyi, O., & Bediako, A. K. (2023). A multicriteria decision framework for governance of PPP projects towards sustainable development. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences, 87, 101580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, R., Bace, B., & Tatar, U. (2024). Space as a critical infrastructure: An in-depth analysis of U.S. and EU approaches. Acta Astronautica, 225, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denis, G., Alary, D., Pasco, X., Pisot, N., Texier, D., & Toulza, S. (2020). From new space to big space: How commercial space dream is becoming a reality. Acta Astronautica, 166, 431–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doboš, B. (2018). Geopolitics of the outer space. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- DOS. (2024). Union Cabinet approves establishment of Rs.1,000 crore venture capital fund for space sector under aegis of IN-SPACe [Press release]. Available online: https://www.pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=2067667 (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- EDGE. (2025). EDGE group: Military contractors defence & military. Available online: https://edgegroup.ae (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K. M. (2021). What is the eisenhardt method, really? Strategic Organization, 19(1), 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K. M., & Graebner, M. E. (2007). Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. Academy of Management Journal, 50(1), 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entrena Utrilla, C. M. (2017). Asteroid-COTS: Developing the cislunar economy with private-public partnerships. Space Policy, 39–40, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzkowitz, H., & Leydesdorff, L. (2000). The dynamics of innovation: From national systems and “mode 2” to a triple helix of university–industry–government relations. Research Policy, 29(2), 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EUTELSAT. (2022). 36 OneWeb satellites successfully launched by ISRO/NSIL from Sriharikota [Press release]. Available online: https://oneweb.net/resources/36-oneweb-satellites-successfully-launched-isro-nsil-sriharikota?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 14 July 2024).

- FAA. (2021). Streamlined launch and reentry license requirements. Available online: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2021/03/09/2021-04068/streamlined-launch-and-reentry-license-requirements?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 17 July 2024).

- FAA. (2024). New record for FAA-licensed commercial space operations, aerospace rulemaking committee launched to update licensing rule. Available online: https://www.faa.gov/newsroom/new-record-faa-licensed-commercial-space-operations-aerospace-rulemaking-committee (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Fazekas, M., Brenner, D., & Ladegaard, P. (2024). Measuring legislative predictability. World Bank Group. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, C. (1995). The ‘national system of innovation’ in historical perspective. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 19(1), 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, J. L., Bolaños, L. A., Daito, N., & Casady, C. B. (2024). What triggers public-private partnership (PPP) renegotiations in the United States? Public Management Review, 26(6), 1583–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B., & Strauss, A. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Aldine Transaction. [Google Scholar]

- Grimsey, D., & Lewis, M. K. (2002). Accounting for public private partnerships. Accounting Forum. [Google Scholar]

- Gunningham, N., Grabosky, P., & Sinclair, D. (1998). Smart regulation: Designing environmental policy. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gustetic, J. L., Crusan, J., Rader, S., & Ortega, S. (2015). Outcome-driven open innovation at NASA. Space Policy, 34, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halchin, L. E. (2008). Other transaction (OT) authority, order code RL34760, CRS report for congress, congress research service. Available online: https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA490439.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Harding, R. C. (2012). Space policy in developing countries: The search for security and development on the final frontier. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hartwich, F., & Tola, J. (2007). Public–private partnerships for agricultural innovation: Concepts and experiences from 124 cases in Latin America. International Journal of Agricultural Resources, Governance and Ecology, 6(2), 240–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodge, G. A., & Greve, C. (2007). Public-private partnerships: An international performance review. Public Administration Review, 67(3), 545–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, M., & Blount, P. (2018). Emerging commercial uses of space: Regulation reducing risks. The Journal of World Investment & Trade, 19(5–6), 1001–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howlett, M. (2023). Designing public policies: Principles and instruments. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hussainey, K., & Aljifri, K. (2012). Corporate governance mechanisms and capital structure in UAE. Journal of Applied Accounting Research, 13(2), 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IN-SPACe. (2023a). Decadal vision and strategy for Indian. Available online: https://www.inspace.gov.in/sys_attachment.do?sys_id=f461d9698775f1104efb31d60cbb35df (accessed on 14 September 2024).

- IN-SPACe. (2023b). Norms, guidelines and procedures for implementation of indian space policy-2023 in respect of authorization of space activities, chapter II: Authorization process. Available online: https://www.inspace.gov.in/inspace?id=inspace_ngp_update_page (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- InterstellarTechnologies. (2024). Interstellar technologies, selected by JAXA as priority launch provider, signs basic agreement. Available online: https://www.istellartech.com/7hbym/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/20240326_Interstellar-Technologies-Selected-by-JAXA-as-Priority-Launch-Provider-Signs-Basic-Agreement.pdf (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Irvine, T. B. (2022, January 3–7). Emerging technologies, societal trends and the aerospace industry. AIAA SCITECH 2022 Forum, San Diego, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- ispace. (2025). Status update on ispace Mission 2 SMBC x HAKUTO-R venture moon. Available online: https://ispace-inc.com/news-en/?p=7664 (accessed on 7 June 2025).

- ISRO. (2023a). Indian space policy. Available online: https://www.isro.gov.in/media_isro/pdf/IndianSpacePolicy2023.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2024).

- ISRO. (2023b). SSLV-D2/EOS-07 MISSION. Available online: https://www.isro.gov.in/mission_SSLV_D2.html (accessed on 9 October 2024).

- ISRO. (2025). Advancing India’s regional navigation capabilities (NavIC). Available online: https://www.isro.gov.in/NVS-02_Advancing_Navigation_Capabilities.html (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Jakhu, R. S., & Pelton, J. N. (2017). Global space governance: An international study. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- JAXA. (2018). J.SPARC. Available online: https://aerospacebiz.jaxa.jp/solution/j-sparc/projects/ (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- JAXA. (2024). Overview of the space strategy fund (SSF). Available online: https://fund.jaxa.jp/content/uploads/Overview_of_The_SpaceStrategy_Fund.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- JSA. (2024). Norms, guidelines and procedures for implementation of Indian space policy-2023 in respect of authorization of space activities. Available online: https://www.jsalaw.com/newsletters-and-updates/norms-guidelines-and-procedures-for-implementation-of-indian-space-policy-2023-in-respect-of-authorization-of-space-activities/#:~:text=The%20Indian%20National%20Space%20Promotion,”NGP” (accessed on 18 May 2024).

- Kalimullah, N. A., Alam, K. M. A., & Nour, M. (2012). New public management: Emergence and principles. BUP Journal, 1(1), 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Kallender, P. (2016). Japan’s new dual-use space policy: The long road to the 21st century. Institut Français des Relations Internationales. [Google Scholar]

- Kallender, P. (2017). Explaining the logics of Japanese space policy evolution 1969–2016, combining macro- and microtheories, notably the strategic action field framework [Doctoral thesis, Keio University]. [Google Scholar]

- Kallender-Umezu, P. (2013). Enacting Japan’s Basic Law for space activities: Revolution or evolution? Space Policy, 29(1), 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavvadia, H. (2024). Dual use space assets through dual nature funding: Will the European Investment Bank propel EU space activity? European Review of International Studies, 10(3), 325–351. [Google Scholar]

- Kettl, D. F. (2000). The transformation of governance: Globalization, devolution, and the role of government. Public Administration Review, 60(6), 488–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M. (2023a). Coherence to choices informing decisions on public-private partnerships in the space sector [Doctoral thesis, RAND School of Public Policy]. Available online: https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/rgs_dissertations/RGSDA2700/RGSDA2739-1/RAND_RGSDA2739-1.pdf (accessed on 17 April 2024).

- Kim, M. (2023b). Toward coherence: A space sector public-private partnership typology. Space Policy, 64, 101549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozuka, S. (2023). National space law and licensing of commercial space activities in Japan. In I. Baumann, L. J. Smith, & S.-G. Wintermuth (Eds.), Routledge handbook of commercial space law. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lamine, W., Anderson, A., Jack, S. L., & Fayolle, A. (2021). Entrepreneurial space and the freedom for entrepreneurship: Institutional settings, policy, and action in the space industry. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 15(2), 309–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanaj, K., Hollenbeck, J. R., Ilgen, D. R., Barnes, C. M., & Harmon, S. J. (2013). The double-edged sword of decentralized planning in multiteam systems. Academy of Management Journal, 56(3), 735–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, R., & Zervos, S. (1998). Stock markets, banks, and economic growth. The American Economic Review, 88(3), 537–558. [Google Scholar]

- Lindenmoyer, A. (2006). Commercial orbital transportation services (COTS) demonstrations. Available online: https://ntrs.nasa.gov/api/citations/20060050052/downloads/20060050052.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Lindenmoyer, A. (2014). Commercial orbital transportation services. Available online: https://www.nasa.gov/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/sp-2014-617.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2023).

- Lindenmoyer, A., Horkachuck, M., Shotwell, G., Manners, B., & Culbertson, F. (2015). Commercial orbital transportation services (COTS) program lessons learned. Available online: https://ntrs.nasa.gov/citations/20150009324 (accessed on 16 April 2023).

- Link, A. N. (1999). Public/private partnerships in the United States. Industry and Innovation, 6(2), 191–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Link, A. N., & Scott, J. T. (2019). Public/private partnerships: Stimulating competition in a dynamic market. In The social value of new technology (pp. 94–125). Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J., Love, P. E., Davis, P. R., Smith, J., & Regan, M. (2015). Conceptual framework for the performance measurement of public-private partnerships. Journal of Infrastructure Systems, 21(1), 04014023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L&T. (2023). L&T powers ISRO’s moon mission—Chandrayaan 3. Available online: https://www.larsentoubro.com/pressreleases/2023/2023-07-13-lt-powers-isro-s-moon-mission-chandrayaan-3/ (accessed on 20 May 2024).

- Lundvall, B.-Å. (2024). Transformative innovation policy–lessons from the innovation system literature. Innovation and Development, 14(2), 297–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzucato, M., & Robinson, D. K. R. (2018). Co-creating and directing Innovation Ecosystems? NASA’s changing approach to public-private partnerships in low-earth orbit. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 136, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MBRSC. (2025). Mohammed bin rashid space centre (MBRSC). Available online: https://www.mbrsc.ae/ (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Mehta, J. (2024, June 10). Challenges for India’s emerging commercial launch industry. Available online: https://www.thespacereview.com/article/4807/1 (accessed on 1 July 2024).

- Melamed, A., Rao, A., de Rohan Willner, O., & Kreps, S. (2024). Going to outer space with new space: The rise and consequences of evolving public-private partnerships. Space Policy, 68, 101626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubadala. (2024). 2024 annual review. Available online: https://www.mubadala.com (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- Nagendra, N. P., & Basu, P. (2016). Demystifying space business in India and issues for the development of a globally competitive private space industry. Space Policy, 36, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NASA. (2014). NASA’s use of space act agreements. Available online: https://oig.nasa.gov/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/IG-14-020.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- NASA. (2023a). 2023 NASA tipping point selections. NASA.

- NASA. (2023b). Technology readiness levels. Available online: https://www.nasa.gov/directorates/somd/space-communications-navigation-program/technology-readiness-levels/ (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- NASA. (2025a). SBIR/STTR program. Available online: https://www.nasa.gov/sbir_sttr/ (accessed on 8 July 2024).

- NASA. (2025b). Space act agreement (SAA). Available online: https://www.nasa.gov/partnerships/current-space-act-agreements/ (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Newman, C. (2022). Legal and policy dimension of UK spaceports. In Spaceports in Europe. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NOAA. (2015). Office of space commerce. Available online: https://space.commerce.gov/law/office-of-space-commerce/ (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- NSIL. (2022). NSIL signs Contract with HAL (lead member of HAL-L&Tconsortium) for production of 05 nos of PSLV-XL [Press release]. Available online: https://www.nsilindia.co.in/sites/default/files/Press%20Release-%20Contract%20signed%20for%20production%20of%2005%20nos%20PSLV-XL.pdf (accessed on 14 April 2024).

- NSIL. (2023a). 5th annual report 2023-24. Available online: https://www.nsilindia.co.in/sites/default/files/u1/Annual%20Report-2023-24%20-%20English.pdf (accessed on 19 April 2025).

- NSIL. (2023b). Launch services (SSLV, PSLV, GSLV-Mk-II and LVM-3). Available online: https://www.isro.gov.in/NSIL.html (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- NSIL. (2023c). NewSpace india limited (NSIL). Available online: https://www.nsilindia.co.in/sites/default/files/u1/Annual%20Report-2022-23%20-%20English.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Nutt, P. C. (2006). Comparing public and private sector decision-making practices. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 16(2), 289–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2015). State-owned enterprises in the development process. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2015/04/state-owned-enterprises-in-the-development-process_g1g507d4/9789264229617-en.pdf (accessed on 16 September 2024).

- OECD. (2021a). Evolving public-private relations in the space sector. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2021/06/evolving-public-private-relations-in-the-space-sector_c865e704/b4eea6d7-en.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 27 February 2023).

- OECD. (2021b). Space economy for people, planet and prosperity. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/sti/inno/space-forum/space-economy-for-people-planet-and-prosperity.pdf (accessed on 26 February 2023).

- OECD. (2023). The space economy in figures: Responding to global challenges. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2023/12/the-space-economy-in-figures_4c52ae39/fa5494aa-en.pdf (accessed on 16 June 2024).

- OECD. (2024). Investment trends: OECD insights for attracting high-qualityfunding. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/space-economy-investment-trends_9ae9a28d-en.html (accessed on 17 May 2024).

- Oltrogge, D. L., & Christensen, I. A. (2020). Space governance in the new space era. Journal of Space Safety Engineering, 7(3), 432–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olusola Babatunde, S., Opawole, A., & Emmanuel Akinsiku, O. (2012). Critical success factors in public-private partnership (PPP) on infrastructure delivery in Nigeria. Journal of Facilities Management, 10(3), 212–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, S. P. (2006). The new public governance? 1. Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Osei-Kyei, R., & Chan, A. P. (2017). Implementation constraints in public-private partnership: Empirical comparison between developing and developed economies/countries. Journal of Facilities Management, 15(1), 90–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paikowsky, D. (2024). Dual use of space technology: A challenge or an opportunity? Space commercialization in the US after the cold war. In The rise of the commercial space industry: Early space age to the present (pp. 291–306). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- PayloadSpace. (2024). 2024 orbital launch attempts by country. Available online: https://payloadspace.com/2024-orbital-launch-attempts-by-country/ (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Pekkanen, S. M. (2020). Japan’s space power. Asia Policy, 15(2), 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekkanen, S. M., Aoki, S., & Takatori, Y. (2024a). Japan in the new lunar space race. Space Policy, 69, 101577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekkanen, S. M., Aoki, S., & Takatori, Y. (2024b). Japan’s Strategy in the New Lunar Space Race. In Routledge handbook of space policy (pp. 561–576). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Pfandzelter, T., & Bermbach, D. (2023, October 6). Edge computing in low-earth orbit—What could possibly go wrong? 1st ACM Workshop on LEO Networking and Communication, Madrid, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- PIB. (2023a). Rs 3,000 crore contract signed with NewSpace india limited for an advanced communication satellite for Indian army. Available online: https://www.pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1911937 (accessed on 3 July 2024).

- PIB. (2023b). Successfully commissioning of GSAT-24 unlocks one more step towards Aatmanirbhar Bharat: I&B Secretary Sh. Apurva Chandra [Press release]. Available online: https://www.pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1946499 (accessed on 18 October 2024).

- PIB. (2024a). Cabinet approves amendment in the Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) policy on space sector. Press Information Bureau. Available online: https://www.pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=2007876 (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- PIB. (2024b). Empowering India’s space economy: Rs. 1,000 crore venture capital fund initiative for innovation and growth [Press release]. Available online: https://www.pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=2068155 (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- PIB. (2024c). From one digit we are now 200 plus StartUps in space sector’ 100% FDI allowed in space sector [Press release]. Available online: https://www.pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=2062671 (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Pixxel. (2024). The future of satellite miniaturisation in manufacturing. Available online: https://www.pixxel.space/blogs/the-future-of-satellite-miniaturisation-in-manufacturing (accessed on 27 September 2024).

- Porel, T., & Singh, T. K. (2025). Evolution of India’s space industry from dependency to commercialization. New Space, 13(1), 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, H. Z., Miraj, P., Andreas, A., & Perdana, R. (2022). Research trends, themes and gaps of public private partnership in water sector: A two decade review. Urban Water Journal, 19(8), 782–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajagopalan, R. P., & Stroikos, D. (2024). The transformation of India’s space policy: From space for development to the pursuit of security and prestige. Space Policy, 69, 101633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rausser, G., Choi, E., & Bayen, A. (2023). Public–private partnerships in fostering outer space innovations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 120, e2222013120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rementeria, S. (2022). Power dynamics in the age of space commercialisation. Space Policy, 60, 101472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, D. K. R., & Mazzucato, M. (2019). The evolution of mission-oriented policies: Exploring changing market creating policies in the US and European space sector. Research Policy, 48(4), 936–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roehrich, J. K., Lewis, M. A., & George, G. (2014). Are public–private partnerships a healthy option? A systematic literature review. Social Science & Medicine, 113, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadeh, E. (2010). Towards a national space strategy. Astropolitics, 8(2–3), 73–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeh, E. (2013). Space strategy in the 21st century: Theory and policy. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- SAPCENEWS. (2024). SpaceX launches latest SES broadcast satellite. Available online: https://spacenews.com/spacex-launches-latest-ses-broadcast-satellite/ (accessed on 6 April 2025).

- Savas, E. S., & Savas, E. S. (2000). Privatization and public-private partnerships. CQ Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sawako, M. (2009). Transformation of Japanese space policy: From the “peaceful use of space” to “the basic law on space”. Asia-Pacific Journal, 7(44), e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, A. (2023). India’s space policy and counter-space capabilities. Strategic Analysis, 47(2), 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehgal, R., & Dubey, A. M. (2019). Identification of critical success factors for public–private partnership projects. Journal of Public Affairs, 19(4), e1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servaes, J., & Hoyng, R. (2017). The tools of social change: A critique of techno-centric development and activism. New Media & Society, 19(2), 255–271. [Google Scholar]

- SIA. (2024). State of the satellite industry report 2024. Available online: https://sia.org/historic-number-of-launches-powers-commercial-satellite-industry-growth-satellite-industry-association-releases-the-28th-annual-state-of-the-satellite-industry-report/ (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- SJAC. (2024). Japanses: FY2023 survey report on the actual conditions of the space equipment industry—Summary. Available online: https://www.sjac.or.jp/pdf/data/5_R5_uchu.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Space42. (2024). Bayanat and yahsat shareholders approve merger to create SPACE42. Available online: https://space42.ai/en/press-release/2024/bayanat-and-yahsat-shareholders-approve-merger-to-create-space42 (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- SpaceCapital. (2025). Space investment quarterly: Q1 2025. Available online: https://www.spacecapital.com/space-iq (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- SPACENEWS. (2022). UAE To develop and launch advanced radar satellite constellation under new AED3 billion space sector fund. Available online: https://spacenews.com/uae-to-develop-and-launch-advanced-radar-satellite-constellation-under-new-aed3-billion-space-sector-fund/ (accessed on 12 October 2024).

- SPACEONE. (2025). Press Release: SPACE ONE awarded launch services contract for multi-orbit observation demonstration satellite under Ministry of defense demonstration initiative. Available online: https://www.space-one.co.jp/news/index_e.html (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- SPACEX. (2025). STARLINK. Available online: https://www.starlink.com/updates?srsltid=AfmBOoo1i6DYOmDK98Kawn18P02omchEmtpgXM4N_9fKTrraOFw1FMMK (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Steele, S. M. (2023). Human spaceflight: Regulations, legal and geopolitical application throughout the international community and commercial actors. American Journal of Aerospace Engineering, 9, 14–27. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, J. (1995). Models of priority-setting for public sector research. Research Policy, 24(1), 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, D. (2018, April 29). A new era in space flight: The COTS model of commercial partnerships at NASA. 13th Reinventing Space Conference, Cham, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, D., Lindenmoyer, A., French, G., Musk, E., Gump, D., Kathuria, C., Miller, C., Sirangelo, M., & Pickens, T. (2008). NASA’s approach to commercial cargo and crew transportation. Acta Astronautica, 63, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, K. (2005). Administrative reforms and the policy logics of Japanese space policy. Space Policy, 21(1), 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, K. (2013). The contest for leadership in East Asia: Japanese and Chinese approaches to outer space. Space Policy, 29(2), 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, K. (2019). Space policies of Japan, China and India: Comparative policy logic analysis. The Ritsumeikan Journal of International Studies, 31(5), 49–67. [Google Scholar]

- Sykes, A. O. (2003). The least restrictive means. The University of Chicago Law Review, 70(1), 403–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Synspective. (2025). Synspective is selected for METI’s global south co-creation subsidy. Available online: https://synspective.com/press-release/2025/globalsouth-cocreation-subsidy/ (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- Tani-Hatakenaka, M. (2023). Public-private partnership to promote new entrants to space R&D activities in Japan. In Routledge handbook of commercial space law (pp. 261–276). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, T. (2007, June 19). Maximizing commercial space transportation with a public-private partnership. SpaceOps 2006 Conference, Rome, Italy. [Google Scholar]

- THAICOM. (2024). Thaicom-10 satellite to be launched by SpaceX. Available online: https://www.thaicom.net/thaicom-10-satellite-to-be-launched-by-spacex/ (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- The U.S.–U.A.E. Business Council. (2024). The U.A.E.’s growing space sector report. Available online: https://usuaebusiness.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/SectorUpdate_SpaceSector_Web.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Tinoco, J. K. (2018). Public-private partnerships in transportation: Lessons learned for the new space era. World Review of Intermodal Transportation Research, 7(1), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinoco, J. K., & Yu, C. (2016). Emerging business models for commercial spaceports: Current trends from the US perspective. Available online: https://portfolio.erau.edu/ws/portalfiles/portal/40012895/Emerging%20Business%20Models%20for%20Commercial%20Spaceports_%20Current%20Trend.pdf (accessed on 19 June 2024).

- Tkatchova, S. (2018). Emerging space markets. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchida, A., Imagawa, K., Yokoyama, T., Sakai, J., Matsuura, M., Toukaku, Y., Nakai, M., Ito, T., Nishikawa, T., Hirai, M., Kaneko, Y., & Yamaguchi, J. (2011). KIBO (Japanese experiment module in ISS) operations—2008/3–2009/10. Acta Astronautica, 68(7), 1318–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UAELegistlation. (2023). Federal decree by law no. (46) of 2023 concerning the regulation of the space sector. The Presidential Palace—Abu Dhabi. Available online: https://u.ae/en/about-the-uae/science-and-technology/key-sectors-in-science-and-technology/space-science-and-technology/space-regulation (accessed on 18 July 2024).

- UAESA. (2019a). National space strategy 2030. Available online: https://u.ae/en/about-the-uae/strategies-initiatives-and-awards/strategies-plans-and-visions/industry-science-and-technology/national-space-strategy-2030 (accessed on 20 May 2024).

- UAESA. (2019b). UAE space policy. Available online: https://space.gov.ae/en/policy-and-regulations (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- UAESA. (2023). Regulation on the authorization of space activities and other activities related to the space sector regulatory framework on space activities of the United Arab Emirates. Available online: https://space.gov.ae/en/policy-and-regulations (accessed on 21 May 2024).

- UAESA. (2024). The national space fund. The United Arab Emirates’Government Portal. Available online: https://u.ae/en/about-the-uae/science-and-technology/key-sectors-in-science-and-technology/space-science-and-technology/the-national-space-fund (accessed on 26 April 2025).

- Uchino, M. (2017, October 1). Can Japan launch itself into becoming a leader in global space business with its new space legislation? (p. 31) International Institute of Space Law. [Google Scholar]

- Ulrichsen, K. (2016). The United Arab Emirates: Power, politics and policy-making. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Uppal, R. (2009). Priority sector advances: Trends, issues and strategies. Journal of Accounting and Taxation, 1(5), 79. [Google Scholar]

- Ustin, S. L., & Middleton, E. M. (2024). Current and near-term earth-observing environmental satellites, their missions, characteristics, instruments, and applications. Sensors, 24(11), 3488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Waldt, G., & Fourie, D. (2022). Ease of doing business in local government: Push and pull factors for business investment in selected South African municipalities. World, 3(3), 470–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernile, A. (2018). The rise of private actors in the space sector. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Vidmar, M. (2021). Enablers, equippers, shapers and movers: A typology of innovation intermediaries’ interventions and the development of an emergent innovation system. Acta Astronautica, 179, 280–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villhard, V., & Hogan, T. (2004). National space transportation policy: Issues for the future. RAND. [Google Scholar]

- Wade, R. (2004). Governing the market: Economic theory and the role of government in East Asian industrialization. Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wakimoto, T. (2019). A guide to Japan’s space policy formulation: Structures, roles and strategies of ministries and agencies for space. Issues & Insights Working Pater, 19. Space Policy Institute. [Google Scholar]

- WAM. (2014). New satellite extends Yahsat’s commercial Ka-band coverage to an additional 17 countries and 600 million users across Africa and Brazil. Available online: https://www.wam.ae/en/article/hsz7ekla-new-satellite-extends yahsat039s-commercial (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- WAM. (2023). Yahsat awarded AED18.7 billion satellite capacity, managed services mandate by UAE government. Available online: https://www.wam.ae/en/article/hszrhzx5-yahsat-awarded-aed187-billion-satellite-capacity (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Ward, M. A., & Mitchell, S. (2004). A comparison of the strategic priorities of public and private sector information resource management executives. Government Information Quarterly, 21(3), 284–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weforum. (2024). EMERGING TECHNOLOGIES, How Japan can remain a star player in the space sector. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/stories/2024/12/space-industry-japan-growth/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- WhiteHouse. (2020a). Advancing america’s global leadership in science & technology trump administration highlights: 2017–2020. Available online: https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Trump-Administration-ST-Highlights-2017-2020.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2023).

- WhiteHouse. (2020b). National space policy united states of America. Available online: https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/National-Space-Policy.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- WhiteHouse. (2021, December 1). United states space priorities framework. Available online: https://bidenwhitehouse.archives.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/12/01/united-states-space-priorities-framework/ (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- WorldBank. (2021). Public-private partnerships in infrastructure. Available online: https://blogs.worldbank.org/ppps/public-private-partnerships-and-2030-agenda-sustainable-development (accessed on 10 May 2023).

- Yin, R. K. (1981). The case study crisis: Some answers. Administrative Science Quarterly, 26(1), 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R. K. (2018). Case study research and applications. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Young, S. L., Welter, C., & Conger, M. (2018). Stability vs. flexibility: The effect of regulatory institutions on opportunity type. Journal of International Business Studies, 49(4), 407–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zancan, V., Paravano, A., Locatelli, G., & Trucco, P. (2024). Evolving governance in the space sector: From legacy space to new space models. Acta Astronautica, 225, 515–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapata, E. (2023). Ingredients and anticipated results for characterizing and assessing NASA and U.S. department of defense partnerships and commercial programs. New Space, 11(2), 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zitron, J. (2006). Public–private partnership projects: Towards a model of contractor bidding decision-making. Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management, 12(2), 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Step | Eisenhardt Process | Application in This Study |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Getting Started | Defined research question; identified six analytically integrated indicators drawn from policy and market theory. |

| 2 | Selecting Cases | Chose four countries representing mature, emerging, and nascent institutional systems. |

| 3 | Crafting Instruments | Developed coding logic with a high–moderate–low classification scheme based on indicator structure. |

| 4 | Entering the Field | Collected data from national space policy documents and space industry reports. |

| 5 | Analyzing Within-Case Data | Independently analyzed each case by six indicators; developed structured country profiles. |

| 6 | Searching for Cross-Case Patterns | Conducted cross case analysis and pairwise pattern comparisons. |

| 7 | Shaping Hypotheses | Derived propositions linking indicator patterns to space PPP model types. |

| 8 | Enfolding Literature | Compared findings with space PPP and innovation system literature. |

| 9 | Reaching Closure | No additional insights or pattern emerged. |

| Indicator | Key Data Sources (All Countries) | |

|---|---|---|

| Policy | P1. National Strategic Goals | National space policy documents, space agency strategies, and planning documents published by relevant government organizations. |

| P2. Government Role Priorities | National space policy documents and government institutional reports. | |

| P3. Regulatory Structure | National space regulations, licensing frameworks, regulatory guidelines, official government documents, and industry regulatory reports. | |

| Market | M1. Capital Access | Space investment databases, venture capital trackers, and multilateral and national investment reports. |

| M2. Private-Sector Capability | Industry capability assessments, national firm-level reports, and technical readiness frameworks. | |

| M3. Commercial Demand | Space market demand reports, industry outlooks, national procurement statistics, and commercial uptake data. |

| Indicator | Classification | Features | Representative Examples | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Policy | (P1) National Strategic Goals | Leadership, National Security | Space as strategic leadership and security domain | 1. The U.S. National Space Policy designates space as a strategic interest, emphasizing leadership and security (WhiteHouse, 2020b, 2021). |

| (P2) Government Role Preference | Enabler | Delegation of routine operations; Space Act agreements; market-shaping ecosystem | 1. Transferring routine operations to private sector and avoiding direct competition (NOAA, 2015; Villhard & Hogan, 2004; WhiteHouse, 2020a). 2. NASA has increasingly relied on milestone-based SAA (Denis et al., 2020). 3. NASA provide advance-purchase commitments and technical insight, while leaving capital investment, and operations to industry (Mazzucato & Robinson, 2018; Tinoco, 2018; Zancan et al., 2024). | |

| (P3) Regulatory Structure | Flexible | Adaptive licensing; procurement flexibility; supportive innovation climate | 1. FAA Part 450 consolidates launch licenses (FAA, 2021). 2. NASA’s use of Space Act Agreements under OTA bypasses FAR constraints (Halchin, 2008; NASA, 2014). 3. Moratorium on human spaceflight safety regulations until 2028; milestone-based contracts (CRS, 2025). | |

| Market | (M1) Capital Access | High | Robust venture capital market; public equity liquidity access; government co-investment mechanism | 1. USD 347.9 billion raised across 2197 space deals (SpaceCapital, 2025). 2. USD 4 billion raised via SPAC mergers with strong public equity access and investor liquidity (BryceTech, 2023). 3. NASA SBIR/STTR (NASA, 2025a) and Tipping Point program (NASA, 2023a). |

| (M2) Private Sector Capability | High | Full value-chain autonomy; launch dominance; downstream maturity | 1. U.S. firms operate across full value chain with TRL 9 systems (NASA, 2023b). 2. 145 of 259 global launches in 2024 (PayloadSpace, 2024). 3. Downstream markets led by firms such as Starlink, Planet, and Maxar (Pfandzelter & Bermbach, 2023). | |

| (M3) Commercial Demand | High | Stable institutional procurement; large domestic and international market | 1. NASA and DOD contract commercial services (Autry, 2018; Rausser et al., 2023; Zapata, 2023). 2. Expanding satellite data services market (SIA, 2024; SPACEX, 2025). 3. International reliance on U.S. launch providers (SAPCENEWS, 2024; THAICOM, 2024) |

| Indicator | Classification | Features | Representative Examples | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Policy | (P1) National Strategic Goals | Security, Scientific Advancement, Market Expansion | Space as a multi- dimensional strategic domain | 1. The strategy integrates three mains interlinked objectives (CAO, 2020, 2025). 2. QZSS and IGS support national defense and civil infrastructure (CAO, 2023). 3. Artemis and ISS collaboration (Araki et al., 2022; Pekkanen et al., 2024a, 2024b; Tsuchida et al., 2011). 4. Large public fund aimed at doubling the industry’s size to JPY 8 trillion (CAO, 2017c). |

| (P2) Government Role Preference | Principal | Mission authority centralized; cabinet-led, multi-ministerial governance; JAXA act as a technical execution agency | 1. Government defines scope, funds development, and oversees system management (Pekkanen, 2020; Tani-Hatakenaka, 2023). 2. Cabinet Office consensus required prior to implementation (Uchino, 2017). 3. JAXA acts as technical agent executing multi-ministry directives (Kallender, 2017). | |

| (P3) Regulatory Structure | Restrictive | Multi-stage licensing with high-level government approval; stringent compliance and liability standards; strictly territorial, which constrains commercial flexibility | 1. Separate licenses required for launch and operation; Prime Ministerial approval mandated under 2016 Space Activities Act (CAO, 2017a, 2017b). 2. Operators must meet detailed requirements; no fast-track options (CAO, 2016; Kozuka, 2023). 3. Licensing applies only to launches within Japanese territory or from Japanese-registered platforms (Aoki, 2009). | |

| Market | (M1) Capital Access | Moderate | Large-scale public funding focused on grants, not equity; limited financial diversity | 1. JPY 1 trillion Space Strategy Fund (SSF) (JAXA, 2024), JAXA unable to make equity investments or issue unrestricted R&D subsidies (Uchino, 2017). 2. Absence of scalable public–private equity partnerships, and externally funded BERD remains rare (OECD, 2024). |

| (M2) Private Sector Capability | Moderate | Private-sector firms active across upstream and downstream, but primarily reliant on government-led programs | 1. In upstream, launch startups have not reached orbit independently (InterstellarTechnologies, 2024; SPACEONE, 2025). 2. Downstream firms operate under state-led programs (Axelspace, 2021; Synspective, 2025). | |

| (M3) Commercial Demand | Low | Demand dominated by government procurement, low export share, and limited demand diversity across sectors | 1. Only 3% of upstream revenue came from exports, and 68% of domestic space sales related to public-sector buyers (SJAC, 2024). 2. “The biggest customer for space-company services still tends to be the government” (Weforum, 2024). |

| Indicator | Classification | Features | Representative Examples | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Policy | (P1) National Strategic Goals | National Security, Economic Development | Space as a dual-purpose strategic domain | 1. Dual national objectives: national security and socio-economic development (ISRO, 2023a). 2. Strategic autonomy through state-controlled indigenous capabilities in launch (PSLV, GSLV, small-lift vehicles) (ISRO, 2023b), navigation (NavIC), and Earth observation (ISRO, 2025). 3. Liberalizing “the entire value-chain” for private-sector participation and expansion of global market share (ISRO, 2023a). |

| (P2) Government Role Preference | Partner | Dual framework: IN-SPACe authorizes private activity; NSIL commercializes ISRO technologies | 1. NSIL’s contract with a HAL-L&T consortium for end-to-end PSLV-XL production (NSIL, 2022). 2. LVM-3 tender under a build–operate–transfer model, marking India’s first heavy-launch PPP (NSIL, 2023b). | |

| (P3) Regulatory Structure | Structured and Predictable | IN-SPACe as a “single window” regulator empowered to issue norms | IN-SPACe’s Norms, Guidelines, and Procedures (NGPs) standardized application processes, 75–120-day statutory review timelines, and objective assessment criteria covering technical readiness, financial solvency, and liability insurance (IN-SPACe, 2023b; JSA, 2024). | |

| Market | (M1) Capital Access | Moderate | FDI liberalization improves cross-border access, but capital ecosystem remains shallow; government-focused venture capital fund | 1. There is 100% foreign ownership in satellite manufacturing and 74% in operations (PIB, 2024b). 2. IN-SPACe-administered INR 1000 crore fund launched for startup finance (DOS, 2024). |

| (M2) Private Sector Capability | Moderate | Private-sector firms active across both upstream and downstream but remain operationally dependent on public infrastructure and contracts | 1. In upstream, Skyroot Aerospace and AgniKul focus on small launch vehicles in the demonstration phase (Bhalodia, 2024). 2. Large firms like L&T operate as ISRO contractors (L&T, 2023). 3. In downstream, Pixxel has deployed EO constellations but remains limited in scale (Pixxel, 2024). | |

| (M3) Commercial Demand | Moderate | Government-led upstream demand; growing downstream demand under government partnership procurement | 1. NSIL’s earned ~USD 360 million via Contracts FY 2022–23 contracts (EUTELSAT, 2022; NSIL, 2023a). 2. GSAT-7B public-funded PPP (PIB, 2023a). 3. NSIL–Tata Play’s GSAT-24 direct-to-home (PIB, 2023b). |

| Indicator | Classification | Features | Representative Examples | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Policy | (P1) National Strategic Goals | Strategic Diversification and Prestige | Space as a platform for global soft power and economic diversification | 1. National space objectives center on two overarching imperatives: economic diversification and international prestige (UAESA, 2019b). 2. The Emirates Mars Mission and astronaut program (Amiri et al., 2022). |

| (P2) Government Role Preference | Principal | Highly centralized and directive; private and international actors contribute as subsystem providers or service contractors | 1. Dubai Sat-1&2 were developed with South Korean partners (Al Harmi, 2016). 2. In the communications domain, Thuraya-4 was developed with Airbus, under state ownership and operational control with Yahsat, a government-owned entity (AIRBUS, 2024; Al Tair, 2017). | |

| (P3) Regulatory Structure | Restrictive | Centralized and discretionary licensing with broad evaluative scope; permission required before entity formation | 1. Federal Decree Law No. 46 in 2023 and the Regulation on the Authorization of Space Activities in 2023 centralized licensing; (UAELegistlation, 2023; UAESA, 2023); Article 5 allows review based on any criteria “deemed appropriate” before granting a license (UAESA, 2023). 2. Prior No-Objection Certificate (NOC) required before entity formation from the Space Agency (UAESA, 2023). | |

| Market | (M1) Capital Access | Low | Dominant government funding and sovereign wealth channels; absence of diverse investment channels | 1. Space Economic Zone and Space Means Business programs for start-ups and small and medium-sized enterprises and National Space Fund (UAESA, 2024). 2. Sovereign entities such as Mubadala and EDGE control strategic financing (EDGE, 2025; Mubadala, 2024). 3. JV firms such as Orbit works and Stellaria rely on state-linked institutions (The U.S.–U.A.E. Business Council, 2024). |

| (M2) Private Sector Capability | Low | Early-stage capability and structurally dependent on government leadership and international collaboration | 1. Hope Probe and Rashid Rover led by MBRSC; all launches procured internationally (Amiri et al., 2022; ispace, 2025; MBRSC, 2025). Downstream initiatives are led by state-affiliated entities such as SPACE42 (Space42, 2024). 2. Startups remain limited to early-stage R&D (The U.S.–U.A.E. Business Council, 2024). | |

| (M3) Commercial Demand | Low | Dominated by state-led demand with limited demand diversity; international demand developing | 1. Yahsat’s Thuraya DTH and VSAT services primarily serve government clients (WAM, 2023). 2. Al Yah 3 expansion into Brazil and Africa is state-backed Via Mubadala and G42 (WAM, 2014). |

| Country | Predominant PPP Models |

|---|---|

| USA | PF-FDO, PFD-FO |

| Japan | PFD, early stage of PFD-FO |

| India | PFD, early stage of PFD-FO |

| UAE | PFD |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kawai, M.; Hanaoka, S. A Decision-Making Framework for Public–Private Partnership Model Selection in the Space Sector: Policy and Market Dynamics Across Countries. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 367. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15090367

Kawai M, Hanaoka S. A Decision-Making Framework for Public–Private Partnership Model Selection in the Space Sector: Policy and Market Dynamics Across Countries. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(9):367. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15090367

Chicago/Turabian StyleKawai, Marina, and Shinya Hanaoka. 2025. "A Decision-Making Framework for Public–Private Partnership Model Selection in the Space Sector: Policy and Market Dynamics Across Countries" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 9: 367. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15090367

APA StyleKawai, M., & Hanaoka, S. (2025). A Decision-Making Framework for Public–Private Partnership Model Selection in the Space Sector: Policy and Market Dynamics Across Countries. Administrative Sciences, 15(9), 367. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15090367