Abstract

In today’s dynamic tourism industry, shaped by globalization and digitalization, understanding destination competitiveness is crucial for crafting sustainable development policies. This paper explores Romania’s competitive advantage as a tourist destination through both theoretical and practical perspectives. The present research aims to diagnose Romania’s level of competitiveness by identifying tourist attributes perceived as relevant by visitors and evaluating their performance relative to other similar European destinations. A quantitative questionnaire-based survey was conducted to achieve this goal. The survey included 235 respondents, gathered through non-probability convenience and snowball sampling. Romania’s competitiveness was assessed using the Competitive Importance-Performance Analysis (CIPA) method, which allowed for the strategic mapping of the country’s position based on the relative performance of essential attributes. These attributes included cultural heritage, the diversity of natural landscapes, the digitalization of tourism services, and staff hospitality. The results highlighted that Romania possesses significant strengths in natural landscapes, gastronomy, accommodation quality, and outdoor activities. However, the study identified major negative gaps in critical areas such as service digitalization, tourist staff attitude, and the quality of cultural events. These findings underscore a latent competitive advantage based on authentic resources, which is currently underexploited from the perspective of modern management and infrastructure. The practical implications of this research provide a solid basis for optimizing tourism marketing policies, efficient resource allocation, and strengthening Romania’s positioning as an authentic, sustainable, and competitive destination within the European landscape.

1. Introduction

As consumer preferences increasingly shift towards memorable experiences over material possessions, tourism has rapidly become a strategic cornerstone of global socio-economic development (UNWTO, 2024; WTTC, 2024). Beyond being a major revenue generator, tourism acts as a catalyst for economic and social progress through its multiplier effects on other economic sectors (Dwyer et al., 2004; Scheyvens, 2011). Amidst globalization, digitalization, and the shifting preferences of tourists towards authentic and sustainable experiences, competition among destinations is more intense than ever (Buhalis & Amaranggana, 2015; Sigala & Marinidis, 2021). These shifts, compounded by recent global events like the COVID-19 pandemic and the growing urgency of climate change impacts on travel patterns, have created a new, more complex environment for destinations to navigate. Under these conditions, a destination’s capacity to leverage its resources, deliver quality services, and foster innovation becomes a critical determinant for its survival and growth. A destination’s competitive advantage is defined by its ability to attract and satisfy visitors while maintaining a distinct market position over the long term (Abreu-Novais et al., 2016; Hall, 2019).

In this dynamic global context, where competition for tourist attention intensifies, countries strive to establish a competitive edge. Romania, despite possessing considerable intrinsic tourism potential stemming from impressive geographical diversity, a rich cultural heritage including 11 UNESCO sites (UNESCO, n.d.), and competitive costs, presents a compelling case of underperformance. The World Economic Forum’s 2024 Travel & Tourism Development Index ranks Romania 43rd out of 119 countries (World Economic Forum, 2024), a position reflecting a notable discrepancy between its authentic resources and modest international market standing (UNESCO, n.d.). This persistent underperformance is further evidenced by structural deficiencies, such as underdeveloped road infrastructure, a low degree of digitalization, and inconsistent promotion of tourism regions (Ministerul Antreprenoriatului și Turismului, 2023). While recent governmental initiatives, like the National Strategy for Tourism Development 2023–2035 (Ministerul Antreprenoriatului și Turismului, 2023), aim for modernization and digitalization, the real valorization of key assets like UNESCO sites remains below potential due to limited accessibility and inefficient administration (Ministerul Turismului, 2019). Consequently, tourist perceptions of hospitality services and cultural experiences often reveal a gap between expectations and actual performance, detrimentally affecting return rates and destination recommendations (Chen & Chen, 2010; Oliver, 1999). This critically emphasizes the necessity of understanding how tourists—both domestic and international—perceive the strengths and weaknesses of the Romanian tourism offering, a crucial step for evaluating competitiveness and substantiating national tourism development strategies (Dwyer & Kim, 2003; Ritchie & Crouch, 2003).

To effectively address these challenges and systematically evaluate destination competitiveness, researchers have relied on various established models and quantitative tools. Previous studies have primarily utilized foundational theoretical frameworks such as Porter’s Diamond (Porter, 1990), which focuses on the macro-level factors and national attributes driving a country’s competitive advantage in global industries, or the Ritchie & Crouch Destination Competitiveness Model (Ritchie & Crouch, 2003), a comprehensive framework that integrates multiple dimensions, including demand, supply, and management, to explain destination competitiveness. Additionally, several qualitative studies have complemented these frameworks by providing an in-depth understanding of tourist perceptions and experiences, often through approaches such as content analysis of user-generated content on social media and online reviews (Garner & Kim, 2022; Lee & Park, 2023) or direct qualitative inquiry (Gârdan et al., 2020).

To complement these foundational frameworks and qualitative studies, researchers have also relied on quantitative tools. Importance-Performance Analysis (IPA) (Martilla & James, 1977) is a technique that assesses attributes based on their perceived importance to tourists and how well a destination performs on those attributes. Its extension, Competitive Importance-Performance Analysis (CIPA) (Taplin, 2012), further refines this by comparing a destination’s performance not just against tourist expectations, but directly against key competitor destinations. For instance, research by Taplin (2012) and Öztürk et al. (2023) applied IPA and CIPA to assess destinations’ perceived performance relative to competitors. While these methodologies have been extensively applied in diverse global contexts—for example, to measure destination competitiveness in Southeast Asia (Mustafa et al., 2020) and to evaluate specific tourism sectors like medical tourism in South Korea (Junio et al., 2017)—their application in the unique environment of Central and Eastern European countries remains limited. For example, similar methods have been used to evaluate destination competitiveness in Serbia (Dwyer et al., 2016; Djeri et al., 2018) and for general destination management (Rašovská et al., 2021). However, most of these studies have relied on only one of the two approaches. Building upon this body of work, our study aims to address this research gap by providing a valuable contribution to the literature.

To address this, the present research employs a dual approach of IPA and CIPA to evaluate Romania’s competitive advantage. This combined application provides a more holistic understanding of a destination’s competitive position, which is particularly relevant for underrepresented regions like Central and Eastern Europe. Our findings will not only provide a more nuanced understanding of Romania’s strategic positioning but will also offer a valuable empirical basis for future research.

Building on this overarching aim, three specific objectives were established. The first objective involves a detailed evaluation of the importance and performance of key attributes defining Romania’s tourism competitiveness from a tourist perspective. The second objective aims at a comparative assessment of Romania with other European destinations, offering vital competitive insights. The third objective focuses on specifically identifying Romania’s negative and positive gaps in competitiveness elements compared to other European tourism destinations.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. The Competitive Advantage of a Tourism Destination

A tourism destination’s competitive advantage is its ability to efficiently and sustainably use its available resources to offer unique, market-tailored tourism experiences, with the ultimate goal of establishing and maintaining a superior position against rival destinations (Porter, 1985). This multifaceted concept extends beyond inherent natural or cultural attractions to incorporate crucial elements such as infrastructure, marketing strategies, and innovation.

The theoretical understanding of competitive advantage has evolved significantly. A foundational perspective, the Resource-Based View (RBV), posits that a destination’s advantage is built on accumulating and leveraging valuable, inimitable resources (Barney, 1991). This view has been complemented by the Dynamic Capabilities Theory, which highlights the critical role of a destination’s ability to adapt and innovate in a changing environment (Teece et al., 1997). This adaptability is essential for transforming a destination’s static resources into a competitive offering.

Alongside these economic and technological considerations, sustainability has emerged as a central and vital element in maintaining competitive advantage (Fennell & Cooper, 2020; UNWTO, 2020a). Responsible tourism, which integrates ecological practices, cultural heritage conservation, and community involvement, is a major competitive differentiator, given the growing interest among tourists for destinations that promote such practices (Lesmana et al., 2022). Building on this, the idea of kinmaking offers a deeper, more ethical perspective by inviting a re-conception of tourism as a co-creation process that fosters enduring relationships among people, places, and ecosystems, sustaining cultural vitality and ecological well-being (Pernecky, 2023).

2.2. Theoretical Models for Evaluating the Competitive Advantage of a Tourism Destination

The evaluation of a tourism destination’s competitive advantage has been significantly advanced by the development and application of a diverse range of theoretical models. These frameworks are essential for assessing destination performance, understanding the complex interactions among key determinants, and optimizing a destination’s position in the international market (Amini et al., 2024; Dias et al., 2023; Gomezelj & Mihalič, 2008; Nematpour et al., 2024; Pavluković et al., 2024; Tőzsér, 2010). Among the most influential and widely used are Porter’s Diamond Model and Ritchie & Crouch’s Destination Competitiveness Model (Faur & Ban, 2022; Jackson, 2018; Ritchie & Crouch, 2003).

Porter’s Diamond Model (Porter, 1990) offers a general framework for analyzing the sources of a country’s competitive advantage, which are essential for its effective international positioning as a destination (e.g., Issakov et al., 2025). The model emphasizes that a nation’s competitiveness in tourism is built upon the success achieved by its tourism sector companies in the international market, as competition occurs primarily among firms, not directly between countries. Consequently, the model examines the linkages between firms and the sources of competitive advantage they can leverage to compete globally (Bouchra & Hassan, 2023).

Porter’s model proposes four interconnected dimensions, each serving as a crucial determinant of competitive advantage (Estevao et al., 2018): Factor Conditions, which refers to a country’s endowment of essential factors of production like infrastructure and specialized labor (Bouchra & Hassan, 2023; Estevao et al., 2018); Firm Strategy, Structure, and Rivalry, which captures how firms are created, managed, and organized, as well as the domestic competition they face (Zhuo, 2012); Demand Conditions, focusing on the nature of domestic demand for the industry’s product (Bankova & Tsvetanova, 2024; Estevao et al., 2018); and Related and Supporting Industries, which encompasses the networks of suppliers and distributors that bolster the industry in international competition (Bankova & Tsvetanova, 2024; Bouchra & Hassan, 2023).

Another key framework is the Destination Competitiveness Conceptual Model (Ritchie & Crouch, 2003). This is an analytical tool that details the determinants of a destination’s competitiveness. The model is structured around five interconnected attribute groups that define a destination’s success: core resources, supporting factors, policy, management, and amplifying determinants. This framework provides a solid conceptual basis for our empirical analysis (Berdo, 2016).

Beyond these broad conceptual models, quantitative tools have also been employed. The Importance-Performance Analysis (IPA) method (Martilla & James, 1977) and its extension, Competitive Importance-Performance Analysis (CIPA) (Taplin, 2012), are widely applied approaches to evaluating competitive advantage. These methodologies have been adopted in a variety of tourism contexts, demonstrating their broad applicability. Relevant examples include medical tourism in Iran (Jalilian et al., 2024), rural destinations (Wang et al., 2022), urban destinations (Wu & Jimura, 2019), cultural tourism (Xiao, 2022), specialized niches like congress tourism (Caber et al., 2017) and thermal tourism (Erbas & Perçin, 2015). Recent studies from Europe, such as an analysis of the Lisbon Metropolitan Area, further demonstrate the contemporary relevance of IPA for assessing destination performance (do Rosário et al., 2024).

This study offers a valuable contribution by addressing a notable gap in the literature. Our choice to use a combined approach of IPA and CIPA is justified by the ability of these models to evaluate tourist perceptions of a destination’s performance and to identify discrepancies between expectations and perceived performance. As the CIPA model allows for the evaluation of a destination’s performance relative to its competitors, our dual approach provides a more holistic understanding of competitiveness. Therefore, our research is grounded in the premise that the combined use of these methods provides a more robust analysis, capturing both a destination’s internal strengths and its external performance (Zhao & Liu, 2024). The application of this dual methodology to the context of Romanian tourism, a market that has been little researched in this way, offers an essential empirical analysis with direct and practical implications for local and national authorities.

2.3. Romania’s Competitive Potential and Strategic Context

Tourism represents a strategic sector for Romania’s economic development, endowed with substantial potential from its diverse geography, rich cultural heritage, and competitive operational costs. Despite these advantages, Romania occupies a modest position among European nations, ranking 43rd out of 119 in the 2024 Travel & Tourism Development Index (World Economic Forum, 2024). This underperformance is largely due to persistent challenges in infrastructure, insufficient promotional efforts, and the absence of a cohesive tourism development strategy. Nevertheless, Romania is highly regarded for its safety, diverse natural and cultural attractions, digital services, and competitive pricing, which offer distinct advantages in attracting a wide range of tourists.

To boost tourism competitiveness and strengthen its image, the National Strategy for Tourism Development 2023–2035 was adopted (Ministerul Antreprenoriatului și Turismului, 2023). This strategy aims to modernize tourism infrastructure through investments, improve accessibility to tourist areas, and upgrade accommodation facilities. It also focuses on developing ecotourism and rural tourism, building on the potential of the country’s mountain regions and natural reserves. This effort is complemented by prior initiatives, such as the 2006 Masterplan for National Tourism Development, which focused on fostering local community development and increasing infrastructure investments (Ministerul Transporturilor, Construcțiilor și Turismului, 2006).

While Romania’s tourism potential is substantial, its competitive edge depends on overcoming existing challenges. According to the Flash Eurobarometer 499 report, natural and cultural attractions are increasingly important for destination selection, which aligns with Romania’s strengths. The country possesses 11 UNESCO cultural heritage sites, with an additional 17 in the process of inscription (UNESCO, 1972). However, many of these sites fail to attract a proportionate number of visitors, often being surpassed by more popular destinations due to limited accessibility, insufficient promotion, and the absence of well-developed tourism products.

A destination’s competitiveness is also significantly influenced by the quality of human interaction and hospitality. The Romanian tourism industry faces challenges in this area, including difficulties in finding and retaining skilled employees, as well as a lack of motivation among staff. Studies on the Romanian hospitality sector have revealed that seasonality drastically affects workforce quality, as candidates are often not motivated to pursue a career in the field (Parteca et al., 2020). Addressing these vulnerabilities is essential for transforming Romania’s natural and cultural assets into a stronger, more resilient competitive advantage.

Infrastructure and accessibility play an essential role. In 2023, Romania had 433,487 tourist accommodation places, with hotels and motels holding the largest share (NIS, n.d.). While the country has 15 international airports, the majority of international arrivals (72.5%) in 2023 were by road, with only 22.7% by air (Romanian Civil Aeronautical Authority [AACR], 2023). This highlights a heavy reliance on road transport and a clear need for further infrastructure improvements. In essence, transforming Romania’s diverse resources into a stronger competitive advantage demands sustained investment and strategic coordination to enhance accessibility, modernize facilities, and develop integrated tourism products.

3. Materials and Methods

To evaluate Romania’s competitive advantage as a tourist destination compared to other countries, we conducted quantitative marketing research. This methodological choice was a deliberate decision, as it was uniquely suited to our objective of assessing visitor perceptions across a broader population. Unlike qualitative research, which provides in-depth insights from a smaller sample, our quantitative approach allowed us to collect standardized, comparable data, which was essential for a reliable competitive benchmarking analysis. The insights gained offer a clear picture of how a specific segment of visitors perceives Romania as a tourist destination and help pinpoint areas needing improvement. It should be noted that due to the use of a non-probability sampling approach (convenience and snowballing), the results are not statistically generalizable to the entire population of tourists, but rather provide a representative snapshot of online-active tourists’ perceptions.

3.1. Research Design and Data Collection Instrument

The present quantitative research utilized a structured, survey-based questionnaire for data collection. Initially, a pilot study involving 50 respondents was conducted to test an extensive questionnaire comprising 39 attributes. The purpose of this pilot study was to evaluate the importance of attributes related to the attractiveness of tourist destinations. These attributes were extracted and adapted from previous studies, including research on destination competitiveness and tourist satisfaction factors (Chen & Tsai, 2007; Dwyer & Kim, 2003; Kozak, 2001; Prideaux, 2000; Ritchie & Crouch, 2003). For evaluating importance, a five-point Likert scale was used, ranging from one (not at all important) to five (very important). Among the attributes included in this pilot study were the quality of tourism and transport infrastructure, the diversity and quality of cultural heritage, the quality of tourism products and services, the conservation and protection of natural resources in the destination, personal and road safety, the availability of medical services, destination reputation/image, presence and promotion on social media and tourism platforms, and the availability of mobile applications and interactive maps for tourists. Following the pilot study and an assessment of item relevance and clarity, 10 essential attributes were selected for the final questionnaire. This reduction from 39 to 10 attributes was systematic and data-driven. The final 10 attributes were chosen based on a preliminary analysis of the pilot study data, which showed they had a consistently high perceived importance among respondents. This ensured that the final questionnaire focused on the most critical factors influencing tourist choice and satisfaction.

The questionnaire was designed to facilitate a Competitive Importance-Performance Analysis (CIPA), providing direct comparative insights into Romania’s competitive standing. It comprised four distinct sections, each serving a specific purpose in gathering the necessary data. The initial section contained two critical screening questions; these were essential for filtering respondents, ensuring that only individuals who had recently visited Romania (e.g., within the last two years) proceeded with the survey, thus guaranteeing the relevance of the collected data to Romania as a tourist destination. Following this, demographic information such as age, gender, and travel frequency was gathered to characterize the respondent population. The third section utilized 5-point Likert scales (ranging from 1 = not at all important/strongly disagree, to 5 = very important/strongly agree) to evaluate the perceived importance and actual performance of various tourist destination attributes specifically for destinations visited in Romania over the past two years. This provided the baseline performance and importance data for the focal destination. In the fourth section, respondents were first asked to identify the last country they visited for tourism. Subsequently, they evaluated the importance and performance of the same 10 attributes for that identified competitor country, using 5-point Likert scales (ranging from 1 = not at all important/strongly disagree, to 5 = very important/strongly agree). This direct, side-by-side evaluation of attributes for both Romania and a recently visited competitor allowed for the immediate identification of Romania’s main competing destinations and provided the necessary data to perform a robust CIPA, thereby revealing Romania’s specific strengths and weaknesses relative to its key competitors as perceived by the tourists.

Data was collected via an online survey disseminated through social media (Facebook, Instagram), tourism forums, and travel groups. We targeted Romanian tourists who had visited both Romania and at least one other country within the last two years. A non-probability sampling approach (convenience and snowball methods) was used, gathering responses from readily available online participants. While this limits rigorous statistical generalization to the broader tourist population, it provides a representative snapshot of online-active tourists’ perceptions. Participation was entirely voluntary. The study was conducted in strict adherence to ethical guidelines for research involving human participants. All respondents were informed about the purpose of the study and the anonymous nature of their responses. By completing and submitting the questionnaire, all participants provided their implied consent to participate in the research. The data was collected and analyzed anonymously, with no personally identifiable information recorded. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the authors’ affiliated institution. The findings are intended for academic publication only and are presented in an aggregated format to ensure the privacy and confidentiality of the respondents.

Additionally, the study focuses on the practical significance of the results, a concept considered crucial for managerial relevance in tourism research (Mohajeri et al., 2020; Onwuegbuzie & Levin, 2003). The substantial magnitude of the differences identified, as seen in the table and figures, provides compelling evidence of meaningful gaps and strengths that have clear implications for strategic decision-making.

3.2. Applying CIPA in Competitiveness Evaluation

We analyzed the collected data using the Competitive Importance-Performance Analysis (CIPA) method. The ultimate goal of this approach was to clearly identify Romania’s competitive advantages and disadvantages against its key competitors.

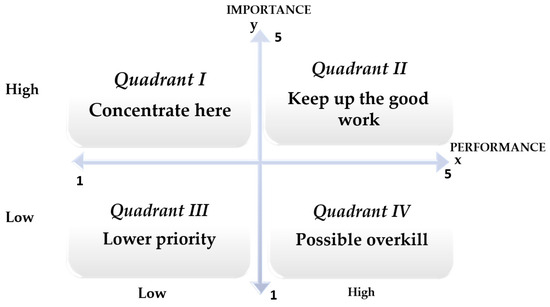

A widely applied practical approach to evaluating competitive advantage is the Importance-Performance Analysis (IPA) method (Martilla & James, 1977) and its extension, CIPA (Taplin, 2012). IPA is represented by a four-quadrant matrix based on two key dimensions: the perceived importance of an attribute and its perceived performance (see Figure 1). Performance refers to a destination’s service delivery as perceived by respondents, while importance reflects their expectations for it. The IPA matrix is divided into four distinct quadrants that guide strategic decision-making:

Figure 1.

The Importance-Performance Analysis Framework (IPA) (Source: Martilla & James, 1977).

- “Concentrate here,” for attributes of high importance but low performance, demanding immediate improvement.

- “Keep up the good work,” for important attributes with high perceived performance, vital for a destination’s sustained success.

- “Lower priority,” for attributes with low importance and low performance, suggesting a re-evaluation of their relevance.

- “Possible overkill,” for attributes with high performance but low importance, indicating potentially inefficient resource allocation.

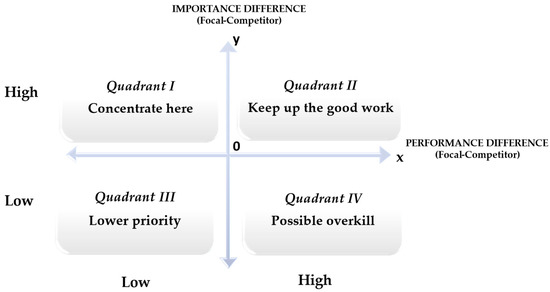

The decision to employ the CIPA model represents a crucial methodological choice, as it introduces a direct comparative dimension essential for a comprehensive analysis of destination competitiveness (Öztürk et al., 2023; Taplin, 2012). As shown in Figure 2, the CIPA matrix evaluates the performance and importance of attributes relative to competitors. Instead of average values, the axes represent the differences between the analyzed destination (Romania) and the average of competing destinations. For example, a negative performance difference and a positive importance difference logically indicate a “Concentrate here” area.

Figure 2.

The Competitive Importance-Performance Analysis Framework (CIPA) (Source: Taplin, 2012).

CIPA offers significant advantages over traditional IPA. Its primary benefit is the competitive dimension, providing a direct comparison with rivals for a clearer understanding of competitive strengths and weaknesses. CIPA also enables the identification of strategic improvement areas necessary to match or surpass competitors. By explicitly including competition, CIPA generates a more detailed matrix, supporting the development of targeted improvement strategies and more informed decision-making (Taplin, 2012; Erbas & Perçin, 2015). This framework is particularly relevant for competitive environments like the tourism industry.

After processing the data, we graphically represented the mean values for each factor. The vertical axis showed the difference in importance between Romania and other destinations, while the horizontal axis displayed the difference in performance. This visualization allowed us to segment the factors into the four distinct quadrants of the CIPA model. Ultimately, the CIPA method provided an integrated analytical framework, helping us pinpoint priority areas for action to boost Romania’s tourism competitiveness.

3.3. Research Hypotheses

Building on the theoretical context and documented challenges discussed above, the present study formulates the following hypotheses to empirically test Romania’s competitive positioning as a tourist destination:

H1.

The perceived performance of Romania regarding its natural and cultural attractions is superior to that of competing destinations, representing a competitive advantage.

H2.

The attitude and hospitality of tourism staff represent a critical vulnerability for Romania compared to competing destinations.

H3.

The perceived performance of Romania regarding its tourism and digital infrastructure is inferior to that of competing destinations, representing a competitive disadvantage.

3.4. Sample Characteristics

235 valid responses were collected from the 243 participants who completed the questionnaire; 8 responses were excluded as they did not meet the screening criterion of having visited at least one country outside Romania. The sample’s socio-demographic characteristics were analyzed by age, gender, and travel frequency. The gender distribution was relatively balanced, with 46.5% male and 53.5% female respondents. The largest age group was 36–45 years old, comprising 64 individuals (27.23%) of the valid responses. Regarding travel frequency, most respondents reported 4 to 6 trips per year (43.4%), with a substantial 36.2% taking 7 to 9 annual trips.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Importance-Performance Analysis (IPA)

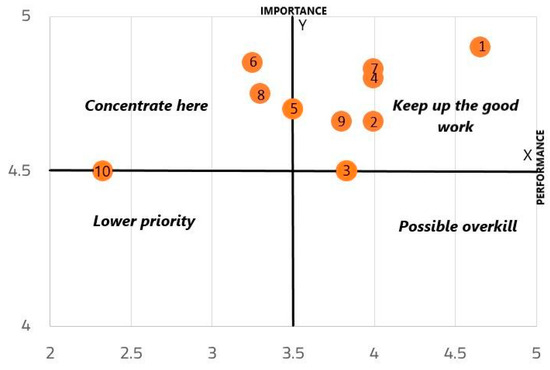

A comparative analysis of the mean scores for importance and performance reveals a detailed perspective on tourist perceptions. The high mean importance scores, which remain consistently above 4.33 for all attributes (as per Table 1), indicate high expectations from tourists. In contrast, the performance scores vary considerably, signaling a notable discrepancy between expectations and the quality of services provided.

Table 1.

Mean importance and performance for analyzed attributes.

Based on these results, attributes falling into the “Keep up the good work” quadrant (Figure 3), with high importance and satisfactory performance, represent key competitive advantages. These include the diversity and beauty of natural landscapes (with the highest performance score), the presence of historical sites, the quality of accommodation, and the authenticity of local gastronomy. They are perceived as essential when choosing a destination and largely meet expectations, contributing to a positive and authentic image of Romania.

Figure 3.

Importance and Performance of Attributes for Romania (IPA Method).

Conversely, the “Concentrate Here” quadrant (Figure 3) highlights critical gaps. The largest negative discrepancies between importance and performance are observed in cleanliness services, mobile applications, outdoor activities, and staff attitude. These aspects are considered very important by tourists, but their performance is significantly below expectations, which indicates an urgent need for strategic intervention.

An analysis of the remaining quadrants offers additional insights for resource allocation. Thus, attributes such as the quality of museums fall into the “Possible Overkill” quadrant (high performance, low importance), suggesting that investments in these areas could be redirected to more critical areas.

4.2. Competitive Importance-Performance Analysis (CIPA)

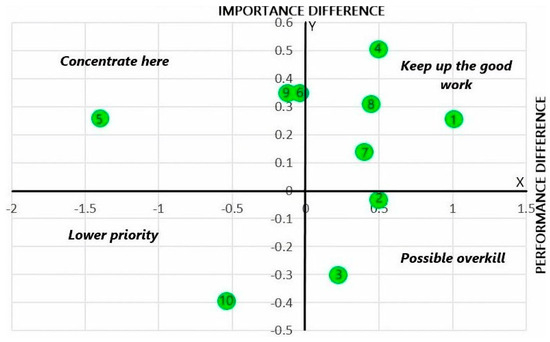

To evaluate Romania’s competitive positioning, we used CIPA analysis, which allowed us to compare perceptions of Romania with those of competing destinations in Europe (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Comparative Evaluation of Attribute Importance and Performance (CIPA Method).

To conduct the CIPA, respondents were asked to select a competitor destination they were most familiar with for comparison to Romania. This approach, while providing a real-world competitive benchmark from the tourist’s perspective, introduces a degree of variability in the comparison base. To provide full transparency and context for our competitive analysis, Table 2 presents a breakdown of the competitor countries chosen by the respondents. As the data shows, the primary competitors for this sample were Hungary, Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey, which together accounted for a significant portion of the comparisons.

Table 2.

Breakdown of Competitor Countries.

The results clearly support hypothesis H1, confirming that Romania holds a distinct competitive advantage in its natural and cultural attractions. This is reflected in the position of the “Keep up the good work” quadrant (Figure 4), which includes attributes with the largest positive performance difference. The diversity of natural landscapes stands out with a performance difference of over 1.0, indicating a strong competitive lead. The quality of accommodation and the authenticity of gastronomy are also positioned as key advantages. These attributes, perceived as superior to competitors, can be strategically leveraged to consolidate Romania’s brand.

On the other hand, CIPA also highlights major competitive disadvantages, supporting hypothesis H2. The attitude and hospitality of tourism staff represent a vulnerable point, with a considerable negative performance difference, signaling a systemic problem in interaction with tourists. Cleanliness services and the quality of cultural events also indicate competitive disadvantages.

The “Lower Priority” quadrant (Figure 4) shows that the digitalization of tourist services, while essential, is perceived as a weakness for Romania compared to its competitors, thus supporting hypothesis H3. This underscores the need to modernize the tourist experience, especially for tourists accustomed to smart technologies. In addition, some attributes, such as the presence of historical sites, fall into the “Possible Overkill” zone, suggesting a potential underutilization of cultural resources in relation to their perceived importance in the competitive market.

4.3. Comparative Discussion: IPA Versus CIPA

A comparative analysis of the IPA and CIPA results reveals significant differences in tourist perceptions, which are contingent on the evaluative context—whether absolute (national) or relative (comparative to other destinations). This crucial distinction provides a more nuanced understanding of Romania’s competitive position.

For several attributes, the two analyses presented a notably different picture. The attitude and hospitality of tourism staff serve as a salient example. While IPA results placed this attribute in the “Concentrate Here” quadrant, suggesting a moderate performance gap, CIPA results revealed a substantially larger negative gap. This indicates that while hospitality is assessed as moderately negative in an isolated evaluation, it becomes a critical weakness when tourists engage in direct comparisons with other destinations they have visited. Similarly, for the quality of cleanliness services, IPA showed a significant absolute deficit. However, CIPA analysis revealed a minor performance difference, suggesting that despite perceived shortcomings, these services are not substantially worse than those in competing destinations, thus mitigating their impact as a major competitive disadvantage. An intriguing pattern also emerged with the availability of mobile applications. While IPA revealed a substantial negative gap, CIPA showed lower perceived importance, shifting this attribute into a “Lower Priority” quadrant. This highlights that while Romania’s digital tools are lacking, they are not a primary concern for tourists relative to other destinations.

Conversely, some attributes consistently exhibited strong performance across both analyses, validating Romania’s authentic competitive advantages. The diversity and beauty of natural landscapes consistently received high scores and performance differences in both IPA and CIPA, underscoring its consolidated competitive advantage and strategic potential in shaping Romania’s tourism brand. Similarly, the quality and diversity of accommodation units were positively perceived in both analyses, with favorable comparisons against other destinations. These findings reinforce the notion that Romania’s accommodation offerings are considered high-performing and superior by tourists, thereby establishing them as authentic and undeniable competitive strengths.

5. Conclusions and Implications

The aim of the present study was to evaluate Romania’s competitive advantage as a tourist destination within an increasingly competitive and dynamic international landscape (Băbăț et al., 2023; Stupariu et al., 2023). Based on our analysis, the findings suggest that Romania possesses significant natural and cultural tourism assets, which aligns with the Resource-Based View (RBV) of competitive advantage by highlighting valuable and unique resources (Barney, 1991). Through the application of both Importance-Performance Analysis (IPA) and Competitive Importance-Performance Analysis (CIPA), we were able to identify distinct strengths as well as critical areas demanding immediate strategic attention. The research highlights strengths as perceived by our respondents, including the diversity and beauty of natural landscapes, authentic local gastronomy, quality and diversity of accommodation, and the availability of outdoor activities. These attributes, positioned in the “Keep Up the Good Work” quadrant of the CIPA matrix, are perceived by participants as both important and well-delivered, positioning Romania competitively against other European destinations. Conversely, the most significant negative discrepancies between importance and performance were identified in the digitalization of tourist services (i.e., lack of mobile applications and interactive maps), cleanliness in accommodation and restaurants, staff attitude and hospitality, and the quality of local cultural events. Consequently, our analysis suggests that Romania possesses a latent competitive advantage rooted in authentic resources, yet the analysis reveals a significant and strategic gap between its potential and its actual market performance, driven by a failure to sufficiently leverage these assets through modern management, effective marketing, and updated infrastructure, a challenge that can be framed within the context of Dynamic Capabilities Theory (Teece et al., 1997).

Based on the study’s findings, several managerial implications and strategic recommendations can be formulated to strengthen Romania’s competitive advantage. To provide a pragmatic and actionable framework, these recommendations are prioritized into three distinct tiers based on established principles of strategic planning, which differentiate between short-term foundational actions and long-term transformational projects. This approach offers a clear roadmap for stakeholders, from individual entrepreneurs to national policymakers.

5.1. Foundational Actions

These are “low-hanging fruit” recommendations that require minimal investment but can yield significant improvements in the short term. They are crucial for creating a solid base and directly addressing the most critical negative gaps identified in the IPA.

- Professionalize hospitality through enhanced service and human interaction. The significant negative gap in staff attitude and hospitality, particularly in the IPA, indicates a critical, yet highly manageable, issue. This challenge, which directly impacts tourist satisfaction, can be addressed through targeted, low-cost interventions. We propose developing a national strategy for professionalizing the tourism workforce by creating dedicated training modules focused on customer service and cross-cultural communication. The link between professionalism and visitor satisfaction is well-documented in the literature (Aideed et al., 2024; Mekoth et al., 2023), highlighting the importance of this factor. Furthermore, implementing mandatory qualification standards for front-office personnel and introducing performance-based incentives can significantly contribute to increasing overall visitor satisfaction and bolstering the destination’s reputation, aligning with modern approaches to developing professional competencies in the hospitality industry (Shevchenko et al., 2020).

- Enhance cleanliness in accommodation and restaurants. The significant negative gap between importance and performance for cleanliness in the IPA highlights an internal service quality issue that can be a major deterrent for potential tourists. This foundational attribute requires immediate, though low-cost, attention. Based on the feedback from our participants, it is crucial to implement monitoring programs for hygiene and cleanliness, incentivize responsible staff, and educate tourists on the importance of maintaining a clean environment. These actions are vital to ensure hygienic standards meet and exceed international levels.

- Revitalize the cultural dimension through enhanced event quality. While Romania’s cultural heritage is recognized as an asset, its potential is underexploited in terms of dynamism and accessibility, as evidenced by a negative gap in the IPA. This finding supports the core argument of the RBV that while a resource is valuable, its true competitive advantage can only be realized through effective leveraging and management. A foundational step to address this is to reconfigure the national cultural calendar to include more frequent and engaging thematic events aligned with tourism seasonality. Integrating heritage into the experience economy through participatory activities (e.g., historical reenactments, craft workshops) and promoting digital storytelling as a narrative tool for historical sites are crucial initial steps.

5.2. Strategic Investments

These recommendations require more substantial planning and resources, with a focus on targeted improvements that will strengthen existing competitive advantages and address strategic weaknesses.

- Enhance outdoor activity infrastructure. The positive CIPA score for outdoor activities confirms their role as a competitive advantage. To fully capitalize on this strength, medium-term investments are required to develop key infrastructure. This includes improving trail markers, establishing equipment rental points, and promoting professional guide services. Such investments could attract a new segment of active and adventure tourists (Ahmed & Nihei, 2024), with a strong emphasis on sustainability and environmental protection.

- Elevate local gastronomy as a core experience. The authenticity of local gastronomy is a clear competitive advantage. Strategic investments are needed to transform this strength into a pillar of the national tourism brand. We recommend integrating gastronomic tourism into national tourism development strategies by organizing regional culinary routes and food festivals. These efforts are crucial for creating a competitive advantage for tourism destinations through unique food and beverage experiences (Knollenberg et al., 2021) and align with the strategic role of gastronomy in destination development (Seyitoğlu & Ivanov, 2020). Fostering collaborations with local farmers and supporting restaurants featuring traditional menus can also serve as powerful differentiators in the European market, contributing to a sustainable tourism destination marketing approach (Baysal & Bilici, 2024).

- Leverage natural landscapes and heritage through thematic routes. The diversity and beauty of Romania’s natural landscapes and the richness of its heritage sites are a clear advantage. Strategic investments should focus on creating curated thematic routes (e.g., hiking, mountain circuits, photography tours) that connect these strengths in a cohesive way. Investing in ecological infrastructure like visitor centers and viewpoints will further enhance the visitor experience and make these assets more accessible and appealing.

5.3. Transformational Projects

These are large-scale, ambitious initiatives that require significant political will and substantial funding. They are essential for a fundamental, long-term shift in Romania’s competitive positioning and for addressing the most significant CIPA gaps.

- Digitalize the tourist experience with an integrated national digital platform. Our research highlights a significant deficit in the availability of digital tools like mobile applications and interactive maps. This gap, a major competitive weakness according to the CIPA, requires a long-term, transformational project to bridge. We propose a comprehensive strategy that integrates digital transformation and rebranding, as these two components are interdependent and crucial for a modern destination’s competitiveness (Mishra et al., 2023). The identified deficit in digital services is a clear indicator of a weakness in the dynamic capabilities of Romania’s tourism sector to adapt to technological advancements (Teece et al., 1997). Therefore, creating a national digital platform, a core element of “smart tourism” infrastructure, should be undertaken in parallel with a national rebranding campaign. This campaign, which should prominently feature Romania’s unique strengths, is essential for building a sustainable future and a resilient brand that can navigate modern challenges (Aman et al., 2024). This strategic approach will not only enhance the tourist experience but also align Romania’s image with its authentic competitive advantages, contributing to the country’s overall strategic resilience and recovery (Garanti et al., 2022; Ravichandran, 2024).

- Sustain and elevate high standards in accommodation. The positive CIPA gap in accommodation quality is a key competitive advantage. A long-term strategy is required to support this advantage and prevent erosion. This involves prioritizing quality certifications, offering incentives for further digitalizing accommodation services, and promoting local guesthouses and hotels that offer authentic and comfortable experiences to maintain their superior position.

- Rebrand Romania for the international market. While not a direct CIPA factor, the overall destination reputation/image is a foundational element. To solidify all other competitive advantages, a long-term, high-commitment national rebranding campaign is necessary. This campaign should prominently feature Romania’s unique strengths (natural beauty, authentic gastronomy, vibrant outdoor activities) to create a distinct and memorable image, moving beyond outdated stereotypes and positioning Romania as a premium destination.

These findings and their associated implications also provide a timely and data-driven justification for leveraging broader macroeconomic and policy frameworks. For instance, the identified gaps in digitalization, infrastructure, and staff training directly align with the strategic objectives of key national and European funding programs, such as those within the Relaunch and Resilience Facility or EU cohesion funds (European Commission, 2021). Consequently, our study’s recommendations are not only actionable for industry stakeholders but also serve as an empirical basis for public policy decisions, enabling Romania to effectively bid for and utilize available funding for tourism-specific projects. Furthermore, a focus on regional cooperation, particularly in promoting cross-border tourist routes and sharing best practices, could address infrastructure and marketing shortcomings that individual destinations cannot resolve alone. This macro-level perspective underscores how addressing the weaknesses identified in our CIPA analysis can directly contribute to strengthening Romania’s overall competitive position within the wider European tourism ecosystem.

Moreover, beyond these national and regional policies, our findings directly align with and respond to key global tourism trends. The identified gap in digitalization and mobile services is particularly critical in a post-pandemic world, where tourists increasingly expect contactless and technology-driven experiences for safety and convenience. This shift towards digital readiness is a major trend identified in recent reports on the future of tourism (UNWTO, 2020b). Similarly, the competitive advantage in natural landscapes and outdoor activities positions Romania as a prime destination for the growing segment of eco-conscious and adventure tourists, a trend fueled by climate change awareness and a desire for authentic, nature-based experiences (Gössling et al., 2020). By strategically focusing on these strengths and addressing weaknesses, Romania can not only improve its competitive standing but also align its tourism model with the future demands of the global market.

Ultimately, by integrating these strategies at a macro, meso, and micro level, leveraging the competitive advantages identified in the CIPA (such as the beauty of natural landscapes, quality accommodation, authentic gastronomy, and outdoor activities), combined with improvements in weaker areas like digitalization, cleanliness, and hospitality, will indirectly, but significantly, enhance Romania’s standing in global tourism competitiveness indicators, including the Travel and Tourism Development Index (TTDI). Consistent implementation of these proposals should lead to an ascension in the TTDI rankings and improved scores across “tourism infrastructure,” “digital readiness,” “safety & security,” and “cultural resources.” This enhanced performance will not only boost Romania’s international image but also attract foreign investment, fostering sustainable sector-wide development. Ultimately, these practical implications extend beyond merely improving the tourism offering; they contribute to solidifying a sustainable, inclusive, and competitive tourism development model. By embracing these strategic directions, Romania can truly transform its natural and cultural resources into lasting strategic advantages, benefiting its economy, communities, and global positioning.

Beyond its practical and managerial implications, this research offers significant theoretical contributions to the understanding of tourism, particularly concerning destination competitiveness and tourist perceptions. First, this study validates and expands the application of both Importance-Performance Analysis (IPA) and Competitive Importance-Performance Analysis (CIPA) within an emerging market, like Romania. This highlights the tools’ relevance in pinpointing specific competitive advantages and disadvantages. A crucial theoretical insight emerges from the detailed comparison of these methods: a participant’s absolute perception of a destination (IPA) can diverge considerably from their relative perception when compared to competitors (CIPA). This distinction is vital for theoretical models of destination competitiveness, suggesting that performance evaluations should always include both perspectives for a comprehensive understanding of market positioning (Ribeiro et al., 2020; Song, 2025). This finding helps to explain why an attribute seen as problematic in absolute terms (e.g., staff hospitality or cleanliness, as found in our IPA analysis) might be perceived differently when benchmarked internationally (in our CIPA analysis), thus influencing differentiation strategies. Second, by identifying the key attributes contributing to Romania’s latent competitive advantage (i.e., natural landscapes, gastronomy, accommodation, outdoor activities) and those acting as barriers (i.e., digitalization, hospitality, cultural events), the study enriches existing literature with concrete empirical evidence from Eastern Europe. This region is often underrepresented in studies compared to more mature tourism markets. Such findings lay the groundwork for developing more nuanced theoretical frameworks that incorporate the unique characteristics of destinations with authentic resources but facing infrastructural and service-level challenges. Finally, this research deepens our understanding of how natural and cultural resources, even when recognized as valuable, can remain underutilized without integrated management, marketing, and digitalization strategies, providing empirical support for the gap between a destination’s inherent potential (as per RBV) and its actual market performance (as per Ritchie & Crouch’s model).

6. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

This study has several limitations, which we have analyzed in detail to understand their potential influence on our findings. First, we used a non-probabilistic convenience and snowball sampling method, relying exclusively on online data collection. While this approach has limitations regarding the generalizability of findings, it is widely recognized and frequently employed in tourism research, particularly when collecting data from niche markets where on-site surveys are challenging (Cunha et al., 2021). The reliance on online platforms for community engagement and data collection is a common practice in modern tourism studies (Hung & Linh, 2025). This approach helps to quickly gather insights, despite the inherent limitations.

While efficient for reaching many respondents, the sample size of 235 respondents impacts the statistical generalizability of our findings. Therefore, the results cannot be considered representative of Romania’s entire tourist population, and the statistical power for any in-depth subgroup analysis (e.g., by nationality or age group) may be low. This sampling method may have introduced a bias towards digitally active tourists, and it could have led to an overemphasis on the importance of mobile applications and interactive maps, potentially explaining the large performance gap observed in this attribute. Furthermore, letting respondents choose their competitor destination introduces a high degree of variability in the comparison baseline, complicating the interpretation of CIPA results against a single, unified benchmark. This study’s conclusions should be interpreted as an exploratory analysis, highlighting specific perceptions and trends rather than definitive, nationwide truths.

Another limitation is the relatively small number of attributes analyzed (10 items), selected based on a pilot study. While these attributes are considered essential, a broader investigation could include a more diverse range of factors influencing competitiveness, such as destination sustainability, sanitary infrastructure specific to medical tourism, or aspects related to cultural diversity at a micro-destination level. The omission of these factors from our analysis means that our conclusions about Romania’s competitiveness are not exhaustive and do not provide a complete view of all potential strengths and weaknesses.

Additionally, this research focused on a general evaluation of Romania as a tourist destination without analyzing the competitiveness of specific tourism forms (e.g., adventure tourism, thematic cultural tourism) or particular micro-destinations in detail. This general approach, while necessary for an initial national diagnosis, may obscure specific competitive advantages or disadvantages that are unique to certain regions or niche tourism products.

Building on these limitations, future research directions emerge to deepen and extend the understanding of Romania’s competitive advantage. First, given the potential sampling bias and generalizability issues identified in our study, future research could employ probabilistic sampling methods or combine online and offline approaches to ensure a more representative sample and more robust results.

Second, in light of our findings being based on a limited number of attributes, a promising direction would be to expand the set of evaluated attributes to cover more facets of the tourist experience, such as sustainability, safety, and sanitary infrastructure, providing an even more detailed picture of tourist perceptions.

Third, considering our study’s focus on a general evaluation of Romania, investigating competitiveness within specific tourism segments (e.g., adventure tourism, thematic cultural tourism) or particular micro-destinations represents another important avenue. This would allow for the identification of niche strategies and more granular competitive advantages.

Furthermore, given the high degree of variability resulting from respondents choosing their own competitor destination, a future analysis could use clustering methods to group competing destinations by type (e.g., Eastern European, Western European, urban, seaside) to reduce data variability and provide a more robust competitive comparison.

Finally, to understand the motivations behind the perceptions we measured, qualitative research, such as in-depth interviews or focus groups with tourists and industry stakeholders, could offer a more nuanced understanding of the reasons behind our findings. As several studies highlight, quantitative research, while excellent for statistical generalization, has inherent limitations in capturing the depth of personal experiences and emotional states (Yuli, 2024; Bideci & Bideci, 2021). Qualitative approaches are uniquely suited for exploring emotional aspects or subjective experiences that were not fully captured by our quantitative questionnaire.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, E.A.; writing—review and editing, visualization, supervision, project administration, E.-N.U. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study, which involved a survey on factors influencing Romania’s tourist competitiveness, was conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the authors’ respective institutions. The research design did not involve any intervention, treatment, or the collection of sensitive personal data. Survey questions were solely opinion-based and did not require participants to disclose personal or sensitive information, ensuring their anonymity regarding their professional roles or personal identity. Participation was entirely voluntary, with participants informed of their right to withdraw at any time without consequence. Given these safeguards, the authors determined that the study posed no more than minimal risk to participants and, therefore, did not require formal ethical approval from an institutional review board or ethics committee.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed verbal consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abreu-Novais, M., Ruhanen, L., & Arcodia, C. (2016). Destination competitiveness: What we know, what we know but shouldn’t and what we don’t know but should. Current Issues in Tourism, 19(6), 492–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Z., & Nihei, T. (2024). Assessing the environmental impacts of adventure tourism in the world’s highest mountains: A comprehensive review for promoting sustainable tourism in high-altitude areas. Journal of Advanced Research in Social Sciences and Humanities, 9(2), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aideed, H., Elbaz, A. M., Salem, I. E., Hussein, H., & Elzek, Y. (2024). The power of professionalism: Enhancing tour guide impact on visitors’ experience and satisfaction to foster visitor sustainable behaviour. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 14673584251350782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aman, E. E., Papp-Váry, Á. F., Kangai, D., & Odunga, S. O. (2024). Building a sustainable future: Challenges, opportunities, and innovative strategies for destination branding in tourism. Administrative Sciences, 14(12), 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini, A., Khodadadi, M., Nikbakht, A., & Nemati, F. (2024). Determinants and indicators for destination competitiveness: The case of Shiraz city, Iran. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 10(4), 1507–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bankova, Y., & Tsvetanova, T. (2024). The diamond model of porter to measure rural regions’ competitiveness: A case from Bulgaria (Vol. 30). Annals of the University Dunarea de Jos of Galati: Fascicle: I, Economics & Applied Informatics. University of National and World Economy. [Google Scholar]

- Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baysal, D. B., & Bilici, N. S. (2024). Gastronomy for sustainable tourism destination marketing. In Cultural, gastronomy, and adventure tourism development (pp. 204–219). IGI Global. [Google Scholar]

- Băbăț, A. F., Mazilu, M., Niță, A., Drăguleasa, I. A., & Grigore, M. (2023). Tourism and travel competitiveness index: From theoretical definition to practical analysis in Romania. Sustainability, 15(13), 10157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdo, S. (2016). The complexity of tourist destination competitiveness concept through main competitiveness models. International Journal of Scientific and Engineering Research, 7(3), 1011–1015. [Google Scholar]

- Bideci, M., & Bideci, C. (2021). Designing a tourist experience for numen seekers. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, 24(5), 704–725. [Google Scholar]

- Bouchra, N. H., & Hassan, R. S. (2023). Application of Porter’s diamond model: A case study of tourism cluster in UAE. In Industry clusters and innovation in the Arab World (pp. 129–156). Emerald Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Buhalis, D., & Amaranggana, A. (2015). Smart tourism destinations: A case study of Ireland. Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism, 2015, 553–564. [Google Scholar]

- Caber, M., Albayrak, T., & İsmayıllı, T. (2017). Analysis of congress destinations’ competitiveness using importance performance competitor analysis. In Journal of convention & event tourism (Vol. 18, No. 2, pp. 100–117). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C. F., & Chen, F. S. (2010). Experience quality, perceived value, satisfaction and behavioral intentions for cruise vacation: The case of Asia tourists. Tourism Management, 31(5), 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. F., & Tsai, D. (2007). How destination image and evaluative factors affect behavioral intentions? Tourism Management, 28(4), 1115–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, D., Kastenholz, E., & Lane, B. (2021). Challenges for collecting questionnaire-based onsite survey data in a niche tourism market context: The case of wine tourism in rural areas. Sustainability, 13(21), 12251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, Á., González-Rodríguez, M. R., & Patuleia, M. (2023). Creative tourism destination competitiveness: An integrative model and agenda for future research. Creative Industries Journal, 16(2), 180–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djeri, L., Stamenković, P., Blešić, I., Milićević, S., & Ivkov, M. (2018). An importance-performance analysis of destination competitiveness factors: Case of Jablanica district in Serbia. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 31(1), 811–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Rosário, J. F., Severino, F. S., Nunes, S., Raposo, Z., Santos, T. C., & de Lurdes Calisto, M. (2024). An importance–performance analysis approach to a tourism destination: The case of Lisbon Metropolitan Area, Portugal. In International conference on tourism research (Vol. 7). ACI. [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer, L., Dragićević, V., Armenski, T., Mihalič, T., & Knežević Cvelbar, L. (2016). Achieving destination competitiveness: An importance–performance analysis of Serbia. Current Issues in Tourism, 19(13), 1309–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, L., Forsyth, P., & Spurr, R. (2004). Tourism’s economic contribution: Factors influencing the results of impact assessments. Tourism Economics, 10(3), 329–341. [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer, L., & Kim, C. (2003). Destination competitiveness: Determinants and indicators. Current Issues in Tourism, 6(5), 369–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erbas, E., & Perçin, N. S. (2015). Competitive Importance Performance Analysis (CIPA): An illustration from thermal tourism destinations. Business and Economics Research Journal, 6(4), 137. [Google Scholar]

- Estevao, C., Nunes, S., Ferreira, J., & Fernandes, C. (2018). Tourism sector competitiveness in Portugal: Applying Porter’s diamond. Tourism & Management Studies, 14(1), 30–44. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. (2021). Romania’s national recovery and resilience plan. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/business-economy-euro/economic-recovery/recovery-and-resilience-facility/country-pages/romanias-recovery-and-resilience-plan_en (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Faur, M., & Ban, O. (2022, May 30-31). Models of tourism destination competitiveness. 39th International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA); Virtually. [Google Scholar]

- Fennell, D. A., & Cooper, C. (2020). Sustainable tourism: Principles, contexts and practices (Vol. 6). Channel View Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Garanti, Z., Violaris, J., Berjozkina, G., & Katemliadis, I. (2022). Rebranding destinations for sustainable tourism recovery post COVID-19 crisis. In COVID-19 and the Tourism Industry (pp. 109–124). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Garner, B., & Kim, D. (2022). Analyzing user-generated content to improve customer satisfaction at local wine tourism destinations: An analysis of Yelp and TripAdvisor reviews. Consumer Behavior in Tourism and Hospitality, 17(4), 413–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gârdan, D. A., Dumitru, I., Gârdan, I. P., & Paștiu, C. A. (2020). Touristic SME’s competitiveness in the light of present challenges—A qualitative approach. Sustainability, 12(21), 9191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomezelj, D. O., & Mihalič, T. (2008). Destination competitiveness—Applying different models, the case of Slovenia. Tourism Management, 29(2), 294–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S., Scott, D., & Hall, C. M. (2020). Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(1), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C. M. (2019). Constructing sustainable tourism development: The 2030 agenda and the managerial ecology of sustainable tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(7), 1044–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, N. P., & Linh, D. T. T. (2025). Residents’ support for tourism development: Influences of the theory of planned behavior and local online community engagement. Quality & Quantity, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issakov, Y., Aktymbayeva, A., Savanchiyeva, A., Assipova, Z., Taukebayeva, M., Moldagaliyeva, A., Burakov, M., Kai, Z., & Dávid, L. D. (2025). Opportunities and perspectives of formation of the mountain tourism cluster in Almaty agglomeration. Geojournal of Tourism and Geosites, 58(1), 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S. W. (2018). Analysis and application of tourism competitive models to tourism destinations. International Journal of Tourism & Hospitality GIAP Journals, 5(1), 31–35. [Google Scholar]

- Jalilian, H., Khodayari-Zarnaq, R., Rahmani, H., & Torkzadeh, L. (2024). Medical tourism attribute competitiveness: An importance–performance analysis. International Journal of Tourism Research, 26(5), e2770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junio, M. M. V., Kim, J. H., & Lee, T. J. (2017). Competitiveness attributes of a medical tourism destination: The case of South Korea with importance-performance analysis. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 34(4), 444–460. [Google Scholar]

- Knollenberg, W., Duffy, L. N., Kline, C., & Kim, G. (2021). Creating competitive advantage for food tourism destinations through food and beverage experiences. Tourism Planning & Development, 18(4), 379–397. [Google Scholar]

- Kozak, M. (2001). Repeaters’ behavior at two distinct destinations. Annals of Tourism Research, 28(3), 784–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. S., & Park, S. (2023). A cross-cultural anatomy of destination image: An application of mixed-methods of UGC and survey. Tourism Management, 98, 104746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesmana, H., Sugiarto, S., Yosevina, C., & Widjojo, H. (2022). A competitive advantage model for Indonesia’s sustainable tourism destinations from supply and demand side perspectives. Sustainability, 14(24), 16398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martilla, J. A., & James, J. C. (1977). Importance-performance analysis. The Journal of Marketing, 41(1), 77–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekoth, N., Thomson, A. R., & Unnithan, A. (2023). The mediating role of satisfaction on the relationship between professionalism and employee continuity in hospitality industry. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism, 24(4), 477–503. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerul Antreprenoriatului și Turismului. (2023). Strategia națională pentru dezvoltarea turismului 2023–2035. Available online: https://turism.gov.ro/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Strategia-Nationala-pentru-Dezvoltarea-Turismului-2023-2035-1.pdf (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- Ministerul Transporturilor, Construcțiilor și Turismului. (2006). Master plan pentru dezvoltarea turismului național 2007–2026. Available online: https://turism.gov.ro/web/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/masterplan_partea1.pdf (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- Ministerul Turismului. (2019). Strategia națională de Dezvoltare a Ecoturismului—Context, Viziune și Obiective—2019–2029. Aprobată prin Hotărârea de Guvern nr. 358/2019. Publicată în Monitorul Oficial nr. 520 din 26 iunie 2019. Available online: https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocument/219401 (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- Mishra, A., Sahu, S. K., & Kingaonkar, S. (2023). Maa hotels: Rebranding and digital transformation. Asian Journal of Management Cases, 09728201221145224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohajeri, K., Mesgari, M., & Lee, A. S. (2020). When statistical significance is not enough: Investigating relevance, practical significance, and statistical significance. MIS Quarterly, 44(2), 525–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, H., Omar, B., & Mukhiar, S. N. S. (2020). Measuring destination competitiveness: An importance-performance analysis (IPA) of six top island destinations in South East Asia. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 25(3), 223–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Statistics (NIS). (n.d.). Tempo-online. Available online: http://statistici.insse.ro:8077/tempo-online/#/pages/tables/insse-table (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Nematpour, M., Khodadadi, M., Makian, S., & Ghaffari, M. (2024). Developing a competitive and sustainable model for the future of a destination: Iran’s tourism competitiveness. International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Administration, 25(1), 92–124. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, R. L. (1999). Whence consumer loyalty? Journal of Marketing, 63(4)suppl1, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwuegbuzie, A. J., & Levin, J. R. (2003). Without supporting statistical evidence, where would reported measures of substantive importance lead? To no good effect. Journal of Modern Applied Statistical Methods, 2(1), 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, S., Işınkaralar, Ö., Yılmaz, D., & Kesimoğlu, F. (2023). A comparative analysis of some shopping centers in metropol cities of Turkiye using IPA and IPCA methods. EKSEN Dokuz Eylül Üniversitesi Mimarlık Fakültesi Dergisi, 4(2), 70–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parteca, M., Harba, J., Țigu, G., & Anton, E. (2020). Employee skills demand in the hospitality industry: Seasonal vs. non-seasonal tourist destinations. Cactus Tourism Journal, 2(2), 28–35. [Google Scholar]

- Pavluković, V., Kovačić, S., Pavlović, D., Stankov, U., Cimbaljević, M., Panić, A., Radojević, T., & Pivac, T. (2024). Tourism destination competitiveness: An application model for Serbia. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 13567667241261396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pernecky, T. (2023). Kinmaking: Toward more-than-tourism (studies). Tourism Recreation Research, 48(4), 558–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M. E. (1985). Competitive advantage. In New York. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M. E. (1990). The competitive advantage of nations (Section: International Business). Harvard Business Review. [Google Scholar]

- Prideaux, B. (2000). The role of the transport system in destination development. Tourism Management, 21(1), 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rašovská, I., Kubickova, M., & Ryglová, K. (2021). Importance–performance analysis approach to destination management. Tourism Economics, 27(4), 777–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravichandran, S. S. (2024). Destination branding in crisis: Reflections on strategic resilience and recovery. IUP Journal of Brand Management, 21(4), 70–79. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, D., Machado, L. P., & Henriques, P. (2020, June 5–6). Competitiveness of tourist destinations theoretical study of the main models. ICRESH 2020 International Conference on Recent Social Studies and Humanities (Online) Proceedings Book (pp. 43–61), Online. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie, J. B., & Crouch, G. I. (2003). The competitive destination: A sustainable tourism perspective. CABI. [Google Scholar]

- Romanian Civil Aeronautical Authority (AACR). (2023). Activity report year 2023 [Raport de activitate ANUL 2023]. AACR. Available online: https://www.caa.ro/uploads/pages/2024.06.11%20raport%20anual%20CA%202023%2014.06.2024_.pdf (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- Scheyvens, R. (2011). Tourism and poverty. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Seyitoğlu, F., & Ivanov, S. (2020). A conceptual study of the strategic role of gastronomy in tourism destinations. International Journal of Gastronomy and Food Science, 21, 100230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevchenko, N. N., Shevchenko, V. I., & Zaikina, E. N. (2020). Modern approaches to the formation of professional competencies of prospective experts of the hospitality industry. Revista Turismo Estudos e Práticas-RTEP/GEPLAT/UERN, 4, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Sigala, M., & Marinidis, D. (2021). Smart tourism destinations: A review of theory and applications. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 38(3), 273–294. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Z. (2025). Research on assessing comprehensive competitiveness of tourist destinations within cities, based on field theory and competitiveness theory. Sustainability, 17(1), 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stupariu, M. I., Josan, I., Gozner, M., Stașac, M. S., Hassan, T. H., & Almakhayitah, M. Y. (2023). The geostatistical dimension of tourist flows generated by foreign tourists in Romania. GeoJournal Tour. Geosites, 50, 1526–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taplin, R. H. (2012). Competitive importance-performance analysis of an Australian wildlife park. Tourism Management, 33(1), 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D. J., Pisano, G., & Shuen, A. (1997). Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 18(7), 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tőzsér, A. (2010). Competitive tourism destination: Developing a new model of tourism competitiveness [Ph.D thesis, Tourism Management, University of MISKOLC]. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. (n.d.). Romania—UNESCO world heritage centre. UNESCO. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/statesparties/ro (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- UNESCO. (1972). Convention concerning the protection of the world cultural and natural heritage. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/conventiontext/ (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). (2020a). Sustainable tourism for development guidebook: Planning for the future. United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). [Google Scholar]

- United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). (2020b). COVID-19 and tourism: An unprecedented challenge to the global tourism industry. UNWTO. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/covid-19-and-tourism-2020 (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). (2024). UN tourism world tourism barometer. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/tourism-barometer (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Wang, X., Wang, L., Niu, T., & Song, M. (2022). An empirical study on the satisfaction of rural leisure tourism tourists based on IPA method. Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience, 2022(1), 7113456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum. (2024). The Travel & Tourism Development Index 2024: A global framework for the future of travel and tourism. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/publications/travel-tourism-development-index-2024/ (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- World Travel & Tourism Council (WTTC). (2024). World travel & tourism economic impact research. Available online: https://wttc.org/research/economic-impact (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Wu, H., & Jimura, T. (2019). Exploring an importance–performance analysis approach to evaluate destination image. Local Economy, 34(7), 699–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L. (2022). Intangible cultural heritage reproduction and revitalization: Value feedback, practice, and exploration based on the IPA model. Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience, 2022(1), 8411999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuli, S. B. C. (2024). Understanding the dynamics of tourist experience through a qualitative lens: A case study approach in Indonesia. Global Review of Tourism and Social Sciences, 1(1), 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W., & Liu, D. (2024, August 23–25). Multi-objective service improvement based on sentiment analysis of online reviews across multiple groups . 7th International Conference on Information Management and Management Science (pp. 431–436), Beijing, China. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuo, X. (2012). Approaches to develop marine fishing tourism in a Norway and Chinese regions. Marine fishing tourism competitiveness comparison between North Cape and Wenzhou [Master’s thesis, The University of Bergen]. [Google Scholar]