Investigating the Effects of Work Intensification, Illegitimate Tasks and Psychological Detachment from Work on Work–Family Conflict

Abstract

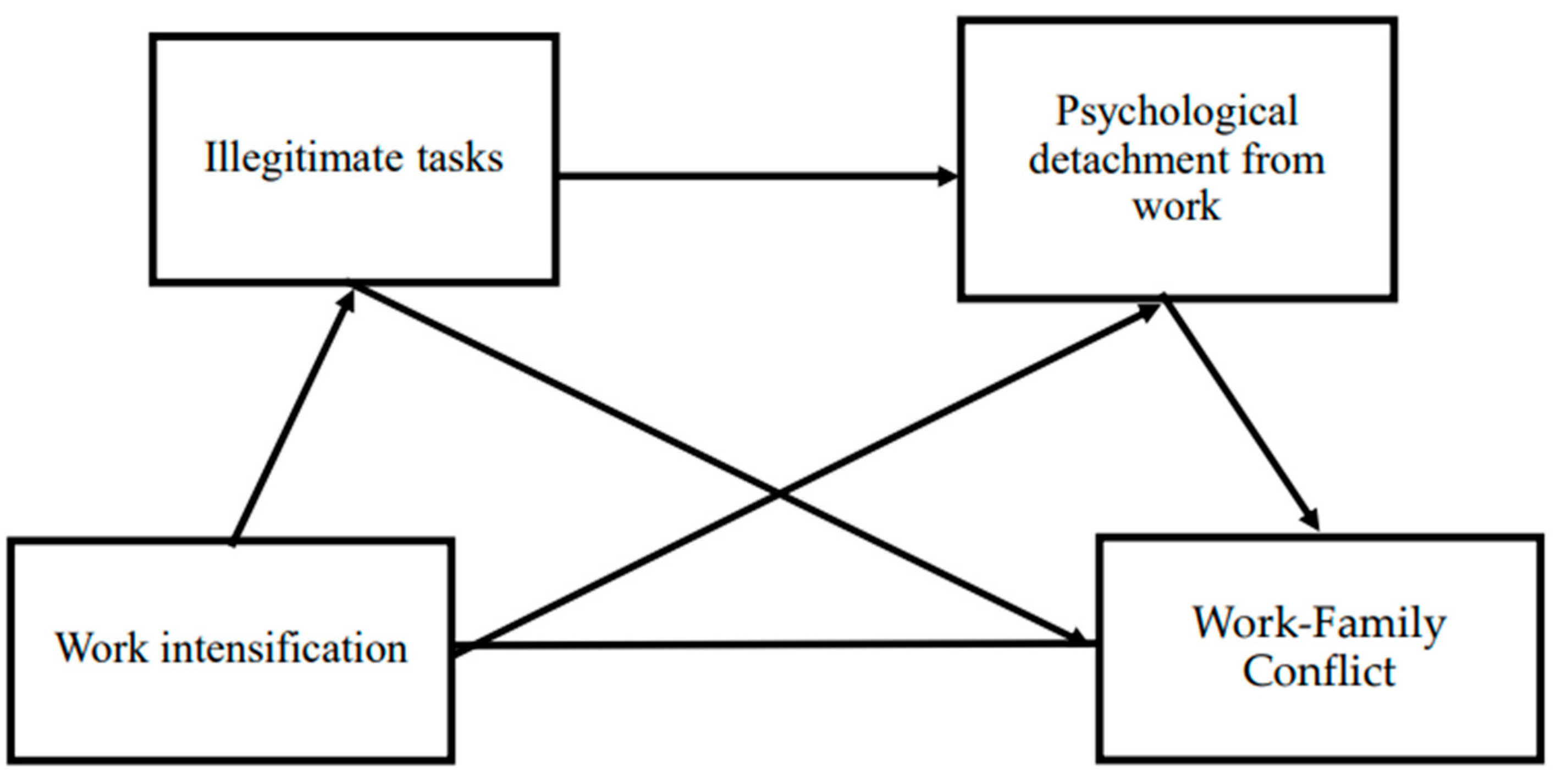

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Work Intensification and Work–Family Conflict

2.2. Mediating Role of Illegitimate Tasks and Psychological Detachment from Work

3. Material and Methods

3.1. Instruments

3.2. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Multicollinearity Test and Common-Method Bias Test

4.2. Correlations Between Variables

4.3. Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

7. Practical and Theoretical Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Allen, T. D., Herst, D. E. L., Bruck, C. S., & Sutton, M. (2000). Consequences associated with work-to-family conflict: A review and agenda for future research. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5, 278–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amstad, F. T., Meier, L. L., Fasel, U., Elfering, A., & Semmer, N. K. (2011). A meta-analysis of work–family conflict and various outcomes with a special emphasis on cross-domain versus matching-domain relations. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 16, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade, C., & Neves, P. C. (2024). Illegitimate tasks and work–family conflict as sequential mediators in the relationship between work intensification and work engagement. Administrative Sciences, 14, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björk, L., Bejerot, E., Jacobshagen, N., & Härenstam, A. (2013). I shouldn’t have to do this: Illegitimate tasks as a stressor in relation to organizational control and resource deficits. Work & Stress, 27, 262–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byron, K. (2005). A meta-analytic review of work–family conflict and its antecedents. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 67, 169–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., & Voydanoff, P. (2009). Does home life interfere with or facilitate performance? Exploring the role of job and home resources. Journal of Vocational Behavior 75, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demsky, C. A., Ellis, A. M., & Fritz, C. (2014). Shrinking boundaries: The spillover of daily work hours into daily recovery. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 35, 895–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eatough, E. M., Meier, L. L., Igic, I., Elfering, A., Spector, P. E., & Semmer, N. K. (2016). You want me to do what? Two daily diary studies of illegitimate tasks and employee well-being. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 37(1), 108–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzion, D., Eden, D., & Lapidot, Y. (1998). Relief from job stressors and burnout: Reserve service as a respite. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83, 577–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frone, M. R., Russell, M., & Cooper, M. L. (1992). Antecedents and outcomes of work-family conflict: Testing a model of the work-family interface. Journal of Applied Psychology, 77, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frone, M. R., Yardley, J. K., & Markel, K. S. (1997). Developing and testing an integrative model of the work–family interface. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 50, 145–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudiino, M., & Di Stefano, G. (2023). Illegitimate tasks and well-being at work: A meta-analysis. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 28, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhaus, J. H., & Beutell, N. J. (1985). Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Academy of Management Review, 10, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2012). PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling [white paper]. Available online: http://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf (accessed on 17 May 2025).

- Hobfoll, S. E. (2001). The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Applied Psychology, 50, 337–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, D., & Kahn, R. L. (1978). The social psychology of organizations (2nd ed.). Wiley. (Original work published 1966). [Google Scholar]

- Kinnunen, U., Feldt, T., Mauno, S., & Rantanen, J. (2011). Interface between work and family: A longitudinal individual and crossover perspective. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83, 119–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossek, E. E., Pichler, S., Bodner, T., & Hammer, L. B. (2011). Workplace social support and work–family conflict: A meta-analysis clarifying the influence of general and work–family-specific supervisor and organizational support. Personnel Psychology, 64, 289–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kottwitz, M. U., Pfister, I. B., Elfering, A., Schummer, S. E., Igic, I., & Otto, K. (2019). SOS—Appreciation overboard! Illegitimacy and psychologists’ job satisfaction. Industrial Health, 57(5), 637–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubicek, B., Paškvan, M., & Korunka, C. (2015). Development and validation of an instrument for assessing work intensification. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 24, 898–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubicek, B., & Tement, S. (2016). Work intensification and the work-home interface: The moderating effect of individual work-home segmentation strategies and organizational segmentation supplies. Journal of Personnel Psychology, 15, 76–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, R. A., Kath, L. M., & Barnes-Farrell, J. L. (2010). A short, valid, predictive measure of work–family conflict: Item selection and scale validation. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 15(1), 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäkikangas, A., Bakker, A., Aunola, K., & Demerouti, E. (2010). Job resources and flow at work: Modelling the relationship via latent growth curve and mixture model methodology. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83(3), 795–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijman, T. F., & Mulder, G. (1998). Psychological aspects of workload. In P. J. D. Drenth, H. Thierry, & C. J. Wolff (Eds.), Handbook of work and organizational psychology (2nd ed., Vol. 2, pp. 5–33). Work psychology. Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Michel, J. S., Kotrba, L. M., Mitchelson, J. K., Clark, M. A., & Baltes, B. B. (2011). Antecedents of work–family conflict: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 32, 689–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, P. C., Andrade, C., Paixão, R., & Silva, J. T. (2023). Portuguese version of bern illegitimate tasks scale: Adaptation and evidence of validity. BMC Psychology, 11(1), 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry-Jenkins, M., & Gerstel, N. (2020). Work and family in the 21st century: Four challenges to scholars. Journal of Marriage and Family, 82, 127–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prem, R., Paškvan, M., Kubicek, B., & Korunka, C. (2018). Exploring the ambivalence of time pressure in daily working life. International Journal of Stress Management, 25(1), 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semmer, N. K., Jacobshagen, N., Meier, L. L., & Elfering, A. (2007). Occupational stress research: The “stress-as-offense-to-self” perspective. In J. Houdmont, & S. McIntyre (Eds.), Occupational health psychology: European perspectives on research, education and practice (Vol. 2, pp. 43–60). ISMAI. [Google Scholar]

- Semmer, N. K., Jacobshagen, N., Meier, L. L., Elfering, A., Beehr, T. A., Kälin, W., & Tschan, F. (2015). Illegitimate tasks as a source of work stress. Work & Stress, 29, 32–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnentag, S., & Fritz, C. (2007). The recovery experience questionnaire: Development and validation of a measure for assessing recuperation and unwinding from work. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 12, 204–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonnentag, S., Mojza, E., Demerouti, E., & Bakker, A. B. (2012). Reciprocal relations between recovery and work engagement: The moderating role of job stressors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97, 842–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnentag, S., Venz, L., & Casper, A. (2017). Advances in recovery research: What have we learned? What should be done next? Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22, 365–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z. E., Eatough, E. M., & Che, X. X. (2020). Effect of illegitimate tasks on work-to-family conflict through psychological detachment: Passive leadership as a moderator. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 121, 103463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Work intensification | 3.83 | 1.45 | - | ||

| 2. Work–family conflict | 3.40 | 1.11 | −0.38 * | - | |

| 3. Illegitimate tasks | 3.83 | 1.25 | 0.45 ** | −0.31 * | - |

| 4. Psych. detachment from work | 2.98 | 1.11 | −0.58 ** | −0.41 * | 0.56 ** |

| Illegitimate Tasks | Psychological Detachment from Work | Work–Family Conflict | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total effects | B | SE | B | SE | B | SE |

| Constant | 3.81 ** | 0.21 | ||||

| Gender * | ||||||

| Work Intensification | −0.15 * | 0.02 | ||||

| F(4,469) = 9.21; p < 0.001; R2 = 0.11 | ||||||

| Constant | 3.19 ** | 0.41 | 3.52 ** | 0.23 | 3.15 ** | 0.26 |

| Work intensification | 0.82 *** | −0.53 * | 0.07 | |||

| Illegitimate tasks | −0.42 ** | 0.67 | ||||

| Work–family conflict | −0.53 ** | |||||

| Gender | ||||||

| F(4,469) = 13.33; p < 0.001; R2 = 0.18 | F(4,469) = 16.21; p < 0.001; R2 = 0.23 | F(4,469) = 22.45; p < 0.001; R2 = 0.25 | ||||

| Indirect effects | ||||||

| Effect | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | ||||

| Total | 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.19 | |||

| WI → IT → PDW | 0.18 | 0.07 | 0.11 | |||

| WI → PDW → WFC | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.08 | |||

| WI → IT → PDW → WFC | 0.14 | 0.04 | 0.07 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Andrade, C.; Neves, P.C. Investigating the Effects of Work Intensification, Illegitimate Tasks and Psychological Detachment from Work on Work–Family Conflict. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 354. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15090354

Andrade C, Neves PC. Investigating the Effects of Work Intensification, Illegitimate Tasks and Psychological Detachment from Work on Work–Family Conflict. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(9):354. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15090354

Chicago/Turabian StyleAndrade, Cláudia, and Paula Costa Neves. 2025. "Investigating the Effects of Work Intensification, Illegitimate Tasks and Psychological Detachment from Work on Work–Family Conflict" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 9: 354. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15090354

APA StyleAndrade, C., & Neves, P. C. (2025). Investigating the Effects of Work Intensification, Illegitimate Tasks and Psychological Detachment from Work on Work–Family Conflict. Administrative Sciences, 15(9), 354. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15090354