Motivation Mix and Agency Reputation: A Person-Centered Study of Public-Sector Workforce Composition

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- What are public employees’ primary workplace motives, and how are they distributed across individuals and agencies?

- (2)

- Which motivational profiles are most prevalent, and how do they vary by sociodemographic characteristics?

- (3)

- How is agency reputation related to the likelihood that employees belong to one profile versus another?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Foundations of Bureaucratic Motivation: From Downs (1967) to Perry (2020)

2.2. Syntheses and Integration of Theoretical Perspectives

2.3. Motivation and Organizational Reputation

3. Empirical Strategy

3.1. Data

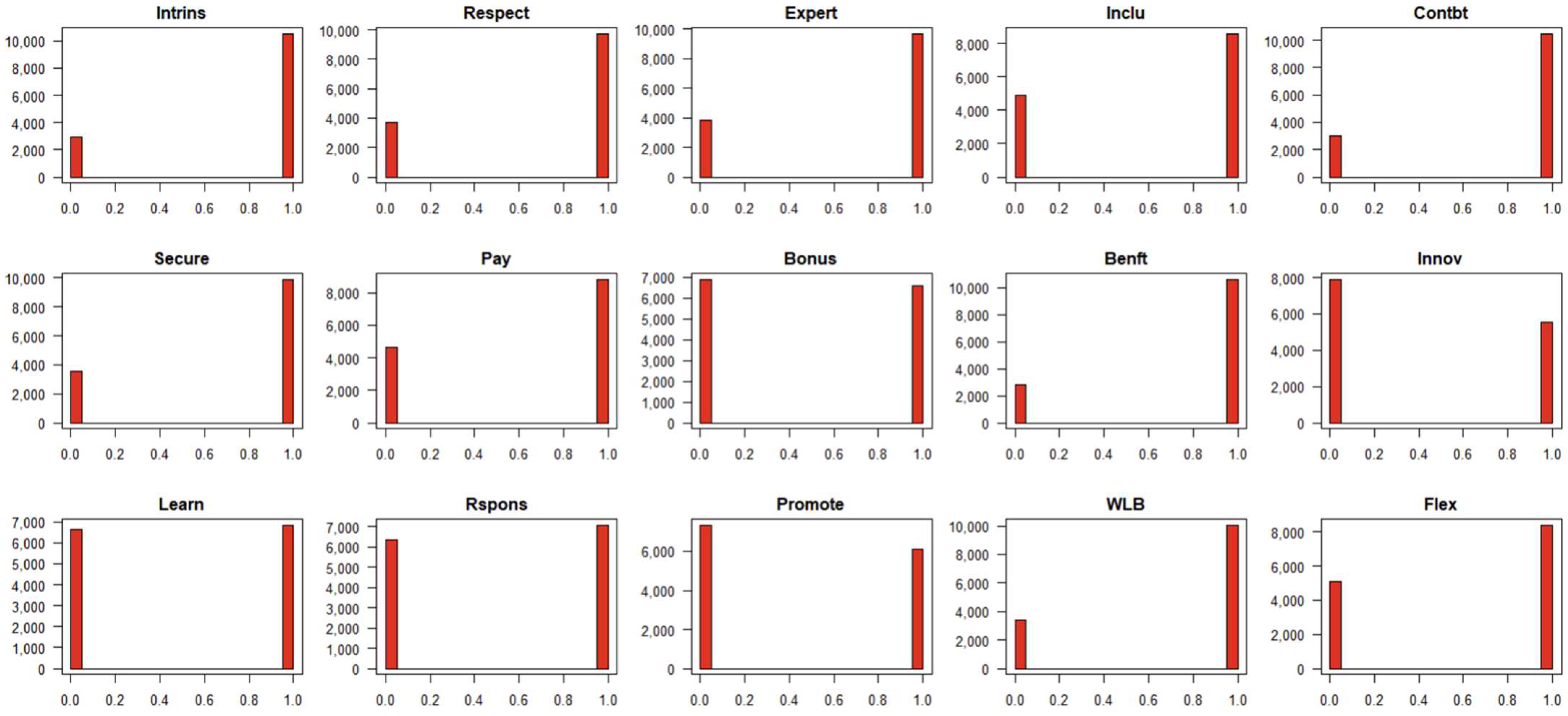

3.2. Measuring Bureaucratic Motivations Based on Key Motives

3.3. Multilevel Latent Class Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Model Selection

4.2. Description of Class and Clusters: Bureaucratic Typology and Agency Types

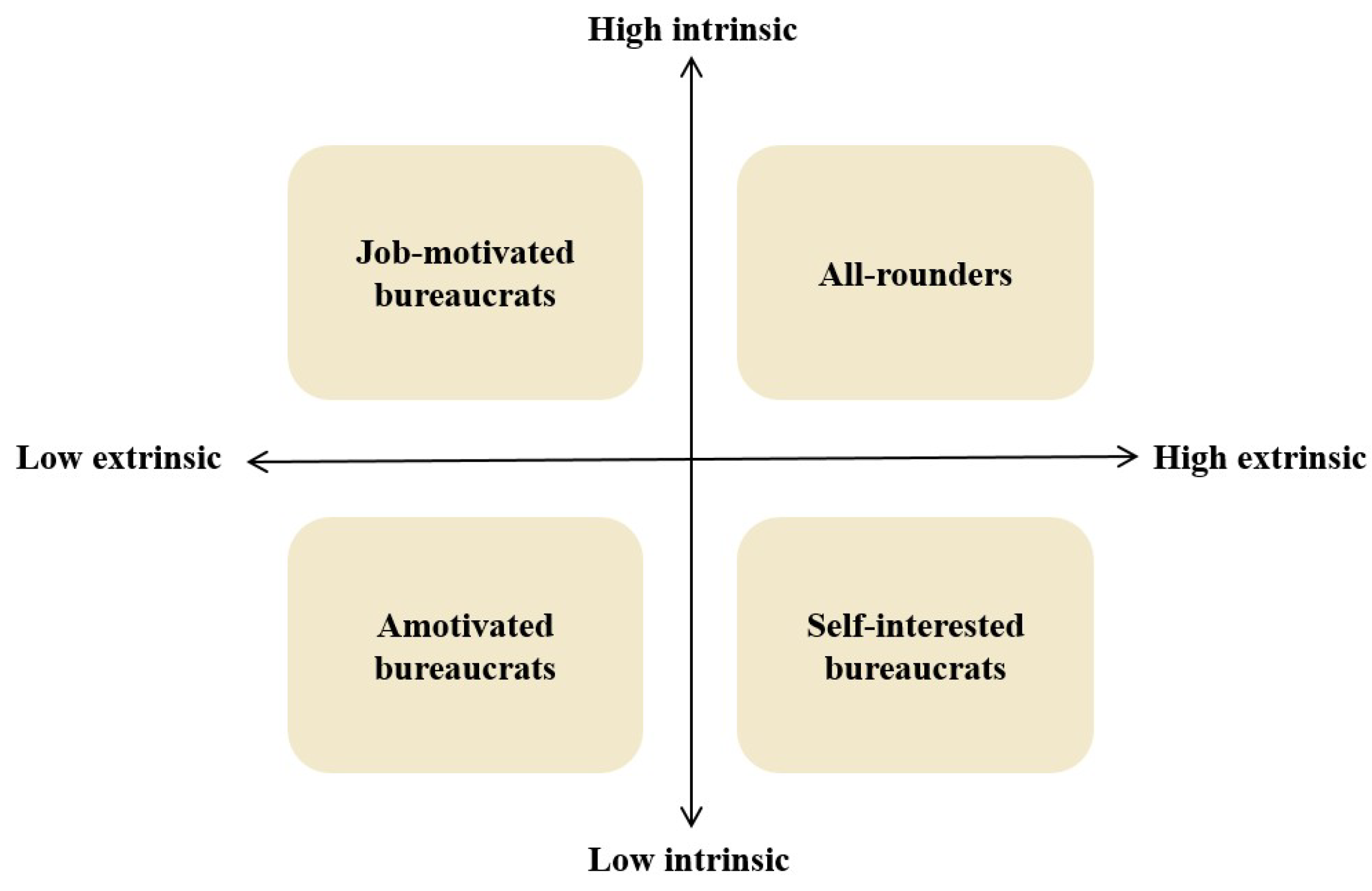

- Class 1: All-rounders

- Class 2: Job-motivated Bureaucrats

- Class 3: Amotivated Bureaucrats

- Class 4: Self-interested Bureaucrats

- Agency types

4.3. Individual and Agency Determinants of Bureaucratic Types

5. Discussion

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OB | Organizational behavior |

| RC | Rational choice |

| PSM | Public service motivation |

| LCA | Latent class analysis |

| OPM | Office of Personnel Management |

| SES | Senior Executive Service |

Appendix A

Appendix B

| Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 |

|---|---|

| Commerce | Air Force |

| Energy | Agriculture |

| EPA | Army |

| Interior | Defense |

| NASA | Justice |

| SEC | Labor |

| State | Education |

| FDIC | |

| GSA | |

| Homeland Security | |

| HUD | |

| Navy | |

| OPM | |

| SSA | |

| Transportation | |

| Treasury | |

| VA |

References

- Albert, S., & Whetten, D. A. (1985). Organizational identity. Research in Organizational Behavior, 7, 263–295. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, A. J., Fuenzalida, J., Gómez, M., & Williams, M. J. (2021). Four lenses on people management in the public sector: An evidence review and synthesis. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 37(2), 335–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasopoulos, J., & Whitford, A. B. (2019). Machine learning for public administration research, with application to organizational reputation. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 29(3), 491–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, L. B., Pedersen, L. H., & Petersen, O. H. (2018). Motivational foundations of public service provision: Towards a theoretical synthesis. Perspectives on Public Management and Governance, 1(4), 283–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arapis, T., & Bowling, C. (2020). From maximizing to minimizing: A national study of state bureaucrats and their budget preferences. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 30(1), 144–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baekgaard, M., Blom-Hansen, J., & Serritzlew, S. (2022). How politicians see their relationship with top bureaucrats: Revisiting classical images. Governance, 35(1), 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellodi, L. (2022). A dynamic measure of bureaucratic reputation: New data for new theory. Americal Journal of Political Science, 67, 880–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertelli, A., Riccucci, N., Canterelli, P., Cucciniello, M., Grose, C., John, P., Linos, E., Thomas, A., & Williams, M. (2022). The (Missing?) role of institutions in behavioral public administration. Journal of Behavioral Public Administration, 5(1), 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertelli, A. M. (2006). Motivation crowding and the federal civil servant: Evidence from the U.S. internal revenue service. International Public Management Journal, 9(1), 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowling, C. J., Cho, C.-L., & Wright, D. S. (2004). Establishing a continuum from minimizing to maximizing bureaucrats: State agency head preferences for governmental expansion—A typology of administrator growth postures, 1964–98. Public Administration Review, 64(4), 489–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, G. A., & Maranto, R. A. (2000). Comparing the roles of political appointees and career executives in the U.S. federal executive branch. American Review of Public Administration, 30(1), 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, G. A., Selden, S. C., & Facer, R. L. (2000). Individual conceptions of public service motivation. Public Administration Review, 60(3), 254–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromley, D. B. (1993). Reputation, image and impression management. Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T. J., Dacin, P. A., Pratt, M. G., & Whetten, D. A. (2006). Identity, intended image, construed image, and reputation: An interdisciplinary framework and suggested terminology. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 34(2), 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustos, E. O. (2021). Organizational reputation in the public administration: A systematic literature review. Public Administration Review, 81(4), 731–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busuioc, E. M., & Lodge, M. (2016). The reputational basis of public accountability. Governance, 29(2), 247–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, D. (2001). The forging of bureaucratic autonomy: Reputations, networks, and policy formation in executive agencies, 1862–1928. Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter, D. (2002). Groups, the media, agency waiting costs, and FDA drug approval. American Journal of Political Science, 46(3), 490–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, D. P., & Krause, G. A. (2012). Reputation and public administration. Public Administration Review, 72(1), 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilulio, J. D. (1994). Principled agents: The cultural bases of behavior in a federal government bureaucracy. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 4(3), 277–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doty, D. H., & Glick, W. H. (1994). Typologies as a unique form of theory building: Toward improved understanding and modeling. Academy of Management Review, 19(2), 230–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downs, A. (1967). Inside bureaucracy. Little, Brown. [Google Scholar]

- Dunleavy, P. (1991). Democracy, bureaucracy and public choice: Economic explanations in political science. Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Dutton, J. E., Dukerich, J. M., & Harquail, C. V. (1994). Organizational images and member identification. Administrative Science Quarterly, 39(2), 239–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteve, M., & Schuster, C. (2019). Motivating public employees (elements in public and nonprofit administration). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fiorina, M. P. (1981). Some problems in studying the effects of resource allocation in congressional elections. American Journal of Political Science, 25(3), 543–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gailmard, S. (2010). Politics, principal-agent problems, and public service motivation. International Public Management Journal, 13(1), 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gailmard, S., & Patty, J. W. (2007). Slackers and zealots: Civil service, policy discretion, and bureaucratic expertise. American Journal of Political Science, 51(4), 873–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gains, F., & John, P. (2010). What do bureaucrats like doing? Bureaucratic preferences in response to institutional reform. Public Administration Review, 70(3), 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodsell, C. T. (2011). Mission mystique: Belief systems in public agencies. CQ Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grimmelikhuijsen, S., Jilke, S., Olsen, A. L., & Tummers, L. (2017). Behavioral public administration: Combining insights from public administration and psychology. Public Administration Review, 77(1), 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackman, J. R., & Oldham, G. R. (1976). Motivation through the design of work: Test of a theory. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 16(2), 250–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameduddin, T., & Lee, S. (2021). Employee engagement among public employees: Examining the role of organizational images. Public Management Review, 23(3), 422–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heclo, H. (1978). Issue networks and the executive establishment. In A. King (Ed.), The new American political system (pp. 262–287). American Enterprise Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Helm, S. (2013). A matter of reputation and pride: Associations between perceived external reputation, pride in membership, job satisfaction and turnover intentions. British Journal of Management, 24(4), 542–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, K. L., & Muthén, B. (2010). Multilevel latent class analysis: An application of adolescent smoking typologies with individual and contextual predictors. Structural Equation Modeling, 17(2), 193–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollibaugh, G. E., Miles, M. R., & Newswander, C. B. (2020). Why public employees rebel: Guerrilla government in the public sector. Public Administration Review, 80(1), 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jilke, S., Olsen, A. L., Resh, W., & Siddiki, S. (2019). Microbrook, mesobrook, macrobrook. Perspectives on Public Management and Governance, 2(4), 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y., & Chung, H. (2024). An R Package for multiple-group latent class analysis • glca. Available online: https://kim0sun.github.io/glca/ (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Kingdon, J. W. (1984). Agendas, alternatives, and public policies. Little, Brown. [Google Scholar]

- Kjeldsen, A. M., & Jacobsen, C. B. (2013). Public service motivation and employment sector: Attraction or socialization? Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 23(4), 899–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasswell, H. (2018). Politics: Who gets what, when, how. Pickle Partners Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S. Y., & Whitford, A. B. (2013). Assessing the effects of organizational resources on public agency performance: Evidence from the US federal government. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 23(3), 687–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Grand, J. (2003). Motivation, agency and public policy: Of knights and knaves, pawns and queens. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Le Grand, J. (2010). Knights and knaves return: Public service motivation and the delivery of public services. International Public Management Journal, 13(1), 56–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, D. (2008). The politics of presidential appointments: Political control and bureaucratic performance. Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Limbocker, S., Resh, W. G., & Selin, J. L. (2021). Anticipated Adjudication: An Analysis of the Judicialization of the US Administrative State. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 32(3), 610–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, M. K., Bray, B. C., & Noll, J. G. (2018). A latent class analysis of online sexual experiences and offline sexual behaviors among female adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 28(3), 731–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mack, G., Ritzel, C., Heitkämper, K., & El Benni, N. (2021). The effect of administrative burden on farmers’ perceptions of cross-compliance-based direct payment policy. Public Administration Review, 81(4), 664–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maor, M. (2015). Theorizing bureaucratic reputation. In A. Wæraas, & M. Maor (Eds.), Organisational reputation in the public sector (pp. 17–36). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Maor, M., Gilad, S., & Bloom, P. B. N. (2013). Organizational reputation, regulatory talk, and strategic silence. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 23(3), 581–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayhew, D. R. (1974). Congress: The electoral connection. Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Meier, K. J., & O’Toole, L. J. (2006). Political control versus bureaucratic values: Reframing the debate. Public Administration Review, 66(2), 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, K. J., O’Toole, L. J., Jr., & O’Toole, L. J. (2006). Bureaucracy in a democratic state: A governance perspective. JHU Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moe, T. M. (1989). The politics of bureaucratic structure. In P. E. Peterson, & J. E. Chubb (Eds.), Can the government govern? (pp. 285–323) The Brookings Institution. [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt, S. L. (2010). Promoting agency reputation through public advice: Advisory committee use in the FDA. Journal of Politics, 72(3), 880–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moynihan, D. P. (2013). Does public service motivation lead to budget maximization? Evidence from an experiment. International Public Management Journal, 16(2), 179–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, B. O., & Muthén, L. K. (2000). Integrating person-centered and variable-centered analyses: Growth mixture modeling with latent trajectory classes. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 24(6), 882–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, V. L., Nielsen, H. Ø., & Bisgaard, M. (2021). Citizen reactions to bureaucratic encounters: Different ways of coping with public authorities. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 31(2), 381–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niskanen, W. A. (1971). Bureaucracy and representative government. Aldine, Atherton. [Google Scholar]

- Nowell, B., & Albrecht, K. (2019). A reviewer’s guide to qualitative rigor. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 29(2), 348–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nørgaard, A. (2018). Human behavior inside and outside bureaucracy: Lessons from psychology. Journal of Behavioral Public Administration, 1(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, R. (2010). Guerrilla employees: Should managers nurture, tolerate, or terminate them? Public Administration Review, 70(1), 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overman, S., Busuioc, M., & Wood, M. (2020). A multidimensional reputation barometer for public agencies: A validated instrument. Public Administration Review, 80(3), 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, S. K., Wright, B. E., & Moynihan, D. P. (2008). Public service motivation and interpersonal citizenship behavior in public organizations: Testing a preliminary model. International Public Management Journal, 11(1), 89–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partnership for Public Service. (2016). 2016 best places to work in the federal government. Partnership for Public Service. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, J. L. (2020). Managing organizations to sustain passion for public service. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, J. L., & Wise, L. R. (1990). The motivational bases of public service. Public Administration Review, 50(3), 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfiffner, J. P. (1987). Political appointees and career executives: The democracy-bureaucracy nexus in the third century. Public Administration Review, 47(1), 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piatak, J. S., & Holt, S. B. (2020). Prosocial behaviors: A matter of altruism or public service motivation? Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 30(3), 504–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piatak, J. S., Sowa, J. E., Jacobson, W. S., & McGinnis Johnson, J. (2020). Infusing public service motivation (PSM) throughout the employment relationship: A review of PSM and the human resource management process. International Public Management Journal, 24, 86–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitkin, H. F. (1967). The concept of representation. University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rainey, H. G. (2014). Understanding and managing public organizations (5th ed.). Jossey-Bass, a Wiley Brand. [Google Scholar]

- Rainey, H. G., & Steinbauer, P. (1999). Galloping elephants: Developing elements of a theory of effective government organizations. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 9(1), 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rho, E., Yun, T., & Lee, K. (2015). Does organizational image matter? Image, identification, and employee behaviors in public and nonprofit organizations. Public Administration Review, 75(3), 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, M. D., Clinton, J. D., & Lewis, D. E. (2018). Elite perceptions of agency ideology and workforce skill. Journal of Politics, 80(1), 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritz, A., Schott, C., Nitzl, C., & Alfes, K. (2020). Public service motivation and prosocial motivation: Two sides of the same coin? Public Management Review, 22(7), 974–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, P. J., & Tang, S.-Y. (1995). The role of commitment in collective action: Comparing the organizational behavior and rational choice perspectives. Public Administration Review, 55(1), 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomonsen, H. H., Boye, S., & Boon, J. (2021). Caught up or protected by the past? How reputational histories matter for agencies’ media reputations. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 31(3), 506–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selin, J. L. (2015). What makes an agency independent? American Journal of Political Science, 59(4), 971–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepsle, K. A. (1991). Discretion, institutions, and the problem of government commitment. In P. Bourdrieu, & J. S. Coleman (Eds.), Social theory for a changing society. Westview Press. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, H. (1997). Administrative behavior: A study of decision-making processes in administrative organizations (4th ed.). Free Press. (Original work published 1947). [Google Scholar]

- Tummers, L., Olsen, A., Jilke, S., & Grimmelikhuijsen, S. (2016). Introduction to the virtual issue on behavioral public administration. Journal of Public Administration Research And Theory, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Van Parys, L., & Struyven, L. (2018). Interaction styles of street-level workers and motivation of clients: A new instrument to assess discretion-as-used in the case of activation of jobseekers. Public Management Review, 20(11), 1702–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermunt, J. K. (2003). Multilevel latent class models. Sociological Methodology, 33(1), 213–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weibel, A., Rost, K., & Osterloh, M. (2010). Pay for performance in the public sector—Benefits and (Hidden) costs. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 20(2), 387–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wise, L. R. (2004). Bureaucratic posture: On the need for a composite theory of bureaucratic behavior. Public Administration Review, 64(6), 669–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, B. E., & Christensen, R. K. (2010). Public service motivation: A test of the job attraction-selection-attrition model. International Public Management Journal, 13(2), 155–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J. (2023). Agency autonomy, public service motivation, and organizational performance. Public Management Review, 25(3), 522–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | N | Mean | SD | Hist. | Min | Median | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Key motives | |||||||

| Interesting work | 13,471 | 0.78 | 0.41 | ▂▁▁▁▇ | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Feeling of respect | 13,471 | 0.72 | 0.45 | ▃▁▁▁▇ | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Opportunity to exercise expertise | 13,471 | 0.72 | 0.45 | ▃▁▁▁▇ | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Being included in decision making processes | 13,471 | 0.64 | 0.48 | ▅▁▁▁▇ | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Making positive contributions | 13,471 | 0.78 | 0.42 | ▂▁▁▁▇ | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Job security | 13,471 | 0.74 | 0.44 | ▃▁▁▁▇ | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Pay | 13,471 | 0.66 | 0.48 | ▅▁▁▁▇ | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Performance-based bonuses | 13,471 | 0.49 | 0.50 | ▇▁▁▁▇ | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Benefits | 13,471 | 0.79 | 0.41 | ▂▁▁▁▇ | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Opportunity to use innovative technology | 13,471 | 0.41 | 0.49 | ▇▁▁▁▆ | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Learning/development opportunities | 13,471 | 0.51 | 0.50 | ▇▁▁▁▇ | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Opportunity for greater responsibility | 13,471 | 0.53 | 0.50 | ▇▁▁▁▇ | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Opportunity for advancement | 13,471 | 0.46 | 0.50 | ▇▁▁▁▆ | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Work-life balance | 13,471 | 0.75 | 0.44 | ▃▁▁▁▇ | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Work flexibility | 13,471 | 0.62 | 0.48 | ▅▁▁▁▇ | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Demographics (level 1) | |||||||

| Agency tenure (1 = 3 years or less, 2 = 4 years or more) | 12,022 | 1.91 | 0.29 | ▁▁▁▁▇ | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Supervisory status | 12,010 | 2.25 | 1.30 | ▇▂▅▂▁ | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Salary | 11,917 | 2.53 | 1.02 | ▅▅▁▇▅ | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| Minority status (0 = non-minority, 1 = minority) | 11,741 | 0.33 | 0.47 | ▇▁▁▁▃ | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Sex (1 = male, 2 = female) | 11,863 | 1.42 | 0.49 | ▇▁▁▁▆ | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Age (1 = 39 and under, 2 = 40 and over) | 11,881 | 1.86 | 0.35 | ▁▁▁▁▇ | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Education (1 = Less than AA, 2 = AA, 3 = Graduate) | 11,938 | 2.22 | 0.73 | ▃▁▇▁▇ | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Agency variables (level 2) | |||||||

| Reputation (Bellodi, 2022) | 13,471 | 0.61 | 0.16 | ▁▁▂▇▆ | 0.05 | 0.61 | 0.82 |

| Reputation (Partnership for Public Service, 2016) | 13,471 | 61.9 | 7.9 | ▂▃▇▂▂ | 45.8 | 63.1 | 80.7 |

| Agency political ideology | 13,471 | 0.26 | 0.96 | ▃▇▅▇▅ | −1.5 | 0.09 | 1.93 |

| Decision making independence (Selin, 2015) | 13,058 | −0.23 | 0.37 | ▇▂___ | −0.69 | −0.36 | 1.31 |

| Political independence (Selin, 2015) | 13,058 | 0.45 | 0.70 | ▇▆___ | −0.36 | 0.37 | 3.57 |

| Agency politicization | 13,058 | 30.7 | 28.2 | ▇▂___ | 0 | 23.6 | 201 |

| Number of Class/Clusters | Log-Likelihood | AIC | CAIC | BIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 Class | −106,269.29 | 212,600.6 | 212,864.3 | 212,833.3 |

| 3 Class | −101,858.78 | 203,811.5 | 204,211.4 | 204,164.4 |

| 4 Class | −99,274.85 | 198,675.7 | 199,211.7 | 199,148.7 |

| 5 Class | −99,220.74 | 198,575.5 | 199,145.5 | 199,078.5 |

| 4 Class/2 Cluster | −96,800.45 | 193,790.9 | 194,599.2 | 194,504.2 |

| 4 Class/3 Cluster | −99,099.88 | 198,463.8 | 199,586.9 | 199,454.9 |

| 4 Class/4 Cluster | −99,099.88 | 198,463.8 | 199,586.9 | 199,454.9 |

| All-Rounder | Job-Motivated | Amotivated | Self-Interested | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence (overall) | 35% | 25% | 16% | 25% |

| Prevalence (cluster 1) | 29% | 33% | 16% | 22% |

| Prevalence (cluster 2) | 36% | 21% | 16% | 26% |

| Indicators (key motives) | ||||

| Interesting work | 0.95 | 0.92 | 0.38 | 0.68 |

| Feeling of respect | 0.96 | 0.80 | 0.18 | 0.67 |

| Exercise expertise | 0.98 | 0.92 | 0.13 | 0.55 |

| Decision making | 0.93 | 0.80 | 0.10 | 0.43 |

| Contribution | 1.00 | 0.93 | 0.27 | 0.67 |

| Job security | 0.97 | 0.50 | 0.32 | 0.92 |

| Pay | 0.95 | 0.28 | 0.23 | 0.89 |

| Performance bonus | 0.85 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.57 |

| Benefits | 0.99 | 0.61 | 0.38 | 0.95 |

| Innovation | 0.83 | 0.24 | 0.05 | 0.24 |

| Learning opportunities | 0.94 | 0.36 | 0.08 | 0.33 |

| Greater responsibility | 0.93 | 0.53 | 0.05 | 0.27 |

| Promotion | 0.78 | 0.42 | 0.07 | 0.29 |

| Work-life balance | 0.97 | 0.63 | 0.34 | 0.84 |

| Work flexibility | 0.88 | 0.41 | 0.23 | 0.73 |

| All-Rounders | Self-Interested | Amotivated | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Level 1 covariates | |||

| Agency tenure (1 = 3 years or less, 2 = 4 years or more) | 0.26 *** | 0.48 | 0.44 *** |

| (0.03) | (0.27) | (0.02) | |

| Supervisory status | −0.23 | −0.40 | −0.26 |

| (0.31) | (0.34) | (0.3) | |

| Salary | −0.40 ** | −0.34 *** | −0.32 |

| (0.12) | (0.02) | (0.18) | |

| Minority status (0 = non-minority, 1 = minority) | 1.26 *** | 0.56 *** | 0.26 |

| (0.13) | (0.11) | (0.28) | |

| Sex (1 = male, 2 = female) | 0.33 | 0.15 | −0.64 *** |

| (0.21) | (0.09) | (0.09) | |

| Age (1 = 39 and under, 2 = 40 and over) | 0.13 *** | −0.20 | 0.01 |

| (0.03) | (0.3) | (0.2) | |

| Education (1 = Less than AA, 2 = AA, 3 = Graduate) | −0.48 | −0.54 | −0.31 *** |

| (0.38) | (0.29) | (0.09) | |

| Level 2 Covariates | |||

| Agency reputation (Bellodi, 2022) | −0.03 *** | −0.06 *** | −0.11 *** |

| (0.00) | (0.01) | (0.03) | |

| Agency reputation (insider-based; Partnership for Public Service, 2016) | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.02 |

| (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | |

| Agency political ideology (Richardson et al., 2018) | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.14 ** |

| (0.22) | (0.09) | (0.07) | |

| Decision making independence (Selin, 2015) | 0.17 | 0.36 *** | 0.1 *** |

| (0.16) | (0.05) | (0.02) | |

| Political independence (Selin, 2015) | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| (0.08) | (0.06) | (0.2) | |

| Agency politicization | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| (0.08) | (0.11) | (0.01) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ahn, Y. Motivation Mix and Agency Reputation: A Person-Centered Study of Public-Sector Workforce Composition. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 353. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15090353

Ahn Y. Motivation Mix and Agency Reputation: A Person-Centered Study of Public-Sector Workforce Composition. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(9):353. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15090353

Chicago/Turabian StyleAhn, Yongjin. 2025. "Motivation Mix and Agency Reputation: A Person-Centered Study of Public-Sector Workforce Composition" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 9: 353. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15090353

APA StyleAhn, Y. (2025). Motivation Mix and Agency Reputation: A Person-Centered Study of Public-Sector Workforce Composition. Administrative Sciences, 15(9), 353. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15090353