Determinants of Student Loyalty and Word of Mouth in Dual VET Secondary Schools in Bulgaria

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Theoretical Foundations

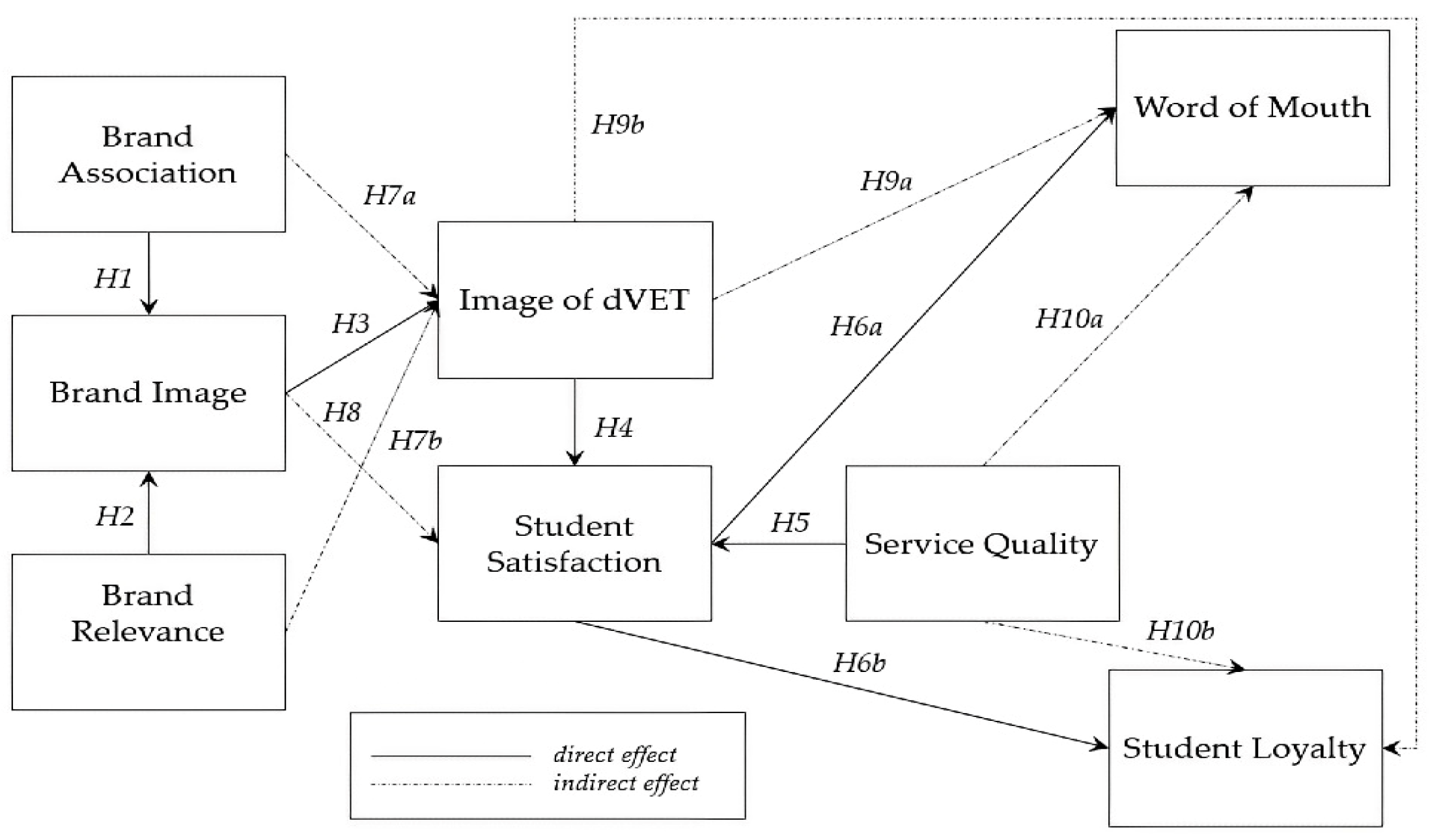

2.2. The Influence of Brand Associations (BA) and Brand Relevance (BR) on Brand Image (BI) of Secondary dVET Schools

2.3. The Influence of Brand Image of Secondary Vocational Schools on Image of dVET (IDVET)

2.4. The Influence of dVET Image and Service Quality (SQ) on Student Satisfaction (SS)

2.5. The Influence of Student Satisfaction on Student Loyalty and Word-of-Mouth Communication

2.6. Brand Image, dVET Image, and Student Satisfaction as Mediators

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Measures

3.2. Participants and Data Collection

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model

4.2. Structural Model

4.2.1. Assessment of Direct Relationships

4.2.2. Assessment of Indirect Relationships

4.2.3. Model Quality and Collinearity Assessment

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical and Managerial Implications

5.2. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASSR | Assurance |

| BA | Brand Associations |

| BE | Brand equity |

| BI | Brand Image |

| BR | Brand Relevance |

| CBBE | Consumer-based Brand Equity |

| CJP | Career and Job Potential |

| CU | Curriculum |

| dVET | Dual Vocational Education and Training |

| EMP | Empathy |

| HES | Higher Education Sector |

| HLIs | Higher Learning Institutes |

| HTMT | Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio of Correlations |

| IDVET | Image of dVET |

| LEQ | Low Entry Qualification |

| MC | Mentors’ Credibility |

| REL | Reliability |

| RES | Responsiveness |

| RVQ | Recognition of Vocational Qualification |

| SEM | Structural Equation Modeling |

| SERVQUAL | Service-Quality Scale |

| SL | Student Loyalty |

| SOF | Soft Skills |

| SQ | Service Quality |

| SMK | Sekolah Menengah Kejuruan |

| SS | Student Satisfaction |

| TAN | Tangibility |

| TFE | Training Facilities and Equipment |

| TVET | Technical and Vocational Education and Training |

| VAF | Variance Accounted For |

| VET | Vocational Education and Training |

| WOM | Word-of-Mouth Communication |

Appendix A. Questionnaire

| Variables | Items 1 2 3 4 5 | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Service Quality | (Elahinia & Karami, 2019; Hasan et al., 2008) | |

| Tangibility | The learning material we study is modern and up to date (TAN1) Number of vocational programs offered (TAN2) Adequacy of computers provided in the classrooms for students (TAN3) Appearance of the building and grounds (TAN4) Degree to which the classrooms and study rooms are comfortable (TAN5) Access to the Internet/e-mail (TAN6) Overall cleanliness (TAN7) | |

| Assurance | Friendly and courteous teachers (ASSR1) Teachers are innovative (ASSR2) Communication skills: lessons are well taught by the teachers in my vocational secondary school (ASSR3) | |

| Reliability | Teachers are punctual and rarely cancel classes (REL1) Teaching capability of mentors (REL2) Teachers’ sincere interest in solving the student’s problem (REL3) | |

| Responsiveness | Teachers’ capacity to solve problems when they arise (RES1) Staff’s capacity to solve problems when they arise (RES2) I seldom get the “run-around” when seeking information from this school (RES3) Channels for expressing student complaints are readily available (RES4) | |

| Empathy | The administration has students’ best interest at heart (EMP1) Access to computer facilities is suited to students’ convenience (EMP2) Access to study rooms is suited to students’ convenience (EMP3) Staff are willing to give students individual attention (EMP4) | |

| Brand Relevance | My school looks modern and up-to-date (BR1) My school provides learning value tailored to my needs (BR2) | (Tran & Duc, 2022) |

| Student Satisfaction | I am satisfied with my decision to attend this school (SS1) I am happy with my decision to enroll in this school (SS2) | (Elahinia & Karami, 2019) |

| Image of dVET | (Awang et al., 2011; Dang & Hathaway, 2014) | |

| Low Entry Qualifications | Vocational students have low learning abilities (LEQ1) My school gives access to all secondary school students (LEQ2) My school has low and flexible entry requirements (LEQ3) | |

| Training Facilities and Equipment | The company where I do my vocational training has proper equipment and the latest technology (TFE1) The company where I train has enough space for good training (TFE2) | |

| Mentors’ Credibility | Helpful mentors (MC1) Experienced mentors (MC2) Qualified mentors (MC3) | |

| Recognition of Vocational Qualification | The dVET qualification is recognized by many private companies in Bulgaria (RVQ1) The dVET qualification is recognized by many foreign companies (RVQ2) The salary is on par with the academic qualifications (RVQ3) | |

| Career and Job Potential | The dVET provides students with strong practical skills (CJP1) The dVET enables the integration of academic knowledge and technical skills (CJP2) The dVET offers a wide range of career selections for graduates (CJP3) The dVET system prepares students to meet the needs of the nation (CJP4) | |

| Curriculum | The theory we learn at school is closely connected to our practical training (CU1) My school maintains strong connections with various industries (CU2) My school offers many interesting opportunities for dual education (CU3) My school is well connected with the local community (CU4) | |

| Soft Skills | DVET graduates have communication skills (SOF6) DVET graduates have leadership skills (SOF7) | |

| Student Loyalty | There is a high probability that I would recommend this school to my friends or acquaintances (SL1) If I had to start over, there is a high chance I would choose the same school again (SL2) | (Nesset & Helgesen, 2009) |

| Brand Image | The name of the school is well known in the Plovdiv region (BI1) The name of the school is associated with high-quality teaching (BI2) My school has a strong brand image (BI3) | (Tran & Duc, 2022) |

| Word of Mouth | I always speak well of this school to people (WOM1) I usually talk about this school with my friends (WOM2) I am honored to tell people that I am studying in this school (WOM3) | (Elahinia & Karami, 2019) |

| Brand Associations | My school offers many opportunities for vocational training (BA1) My school organizes events related to the presentation of various professions and employers (BA3) | (Girard & Pinar, 2020) |

References

- Aaker, D. A. (1991). Managing brand equity: Capitalizing on the value of brand name. The Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Alves, H., & Raposo, M. (2010). The influence of university image on student behaviour. International Journal of Educational Management, 24(1), 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E. W., & Sullivan, M. W. (1993). The Antecedents and Consequences of Customer Satisfaction for Firms. Marketing Science, 12(2), 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriana, R., Astuti, W., & Subiyantoro, E. (2023). Mediation of Student Loyalty on the Influence of Service Quality and Institutional Image on Student Word of Mouth in Indonesia. Dinasti International Journal of Education Management and Social Science, 4(2), 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awang, A. H., Sail, R., Alavi, K., & Ismail, I. A. (2011). Image and students’ loyalty towards technical and vocational education and training. Journal of Technical Education and Training (JTET), 3(1), 13–28. [Google Scholar]

- Bloemer, J., de Ruyter, K., & Peeters, P. (1998). Investigating drivers of bank loyalty: The complex relationship between image, service quality and satisfaction. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 16(7), 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, G., & Edgington, R. (2008). Factors influencing word-of-mouth recommendations by MBA students: An examination of school quality, educational outcomes, and value of the MBA. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 18(1), 79–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo-Porral, C., Lévy-Mangin, J.-P., & Novo-Corti, I. (2013). Perceived quality in higher education: An empirical study. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 31(6), 601–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capriotti, P., & Zeler, I. (2023). Analysing effective social media communication in higher education institutions. Humanit Soc Sci Commun, 10, 656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruana, A. (2002). Service loyalty: The effects of service quality and the mediating role of customer satisfaction. European Journal of Marketing, 36(7/8), 811–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cedefop & ibw Austria. (2023). Vocational education and training in Europe—Austria: System description. In Vocational education and training in Europe: VET in Europe database—Detailed VET system descriptions. Cedefop & ReferNet 2024. Available online: https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/tools/vet-in-europe/systems/austria-u3 (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Chang, J. (2025). The mediating role of brand image in the relationship between storytelling marketing and purchase intention: Case study of PX mart. Future Business Journal, 11, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-T. (2016). The investigation on brand image of university education and students’ word-of-mouth behavior. Higher Education Studies, 6(4), 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahiyat, S. E., Akroush, M. N., & Abu-Lail, B. N. (2011). An integrated model of perceived service quality and customer loyalty: An empirical examination of the mediation effects of customer satisfaction and customer trust. International Journal of Services and Operations Management, 9(4), 453–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, V. H., & Hathaway, T. (2014). Vietnamese students’ perception and loyalty towards an image of vocational education and training. Journal of Education and Vocational Research, 5(4), 228–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, V. H., & Hathaway, T. (2015). The influence of vocational education training image on students’ loyalty: Case study in Vietnam. International Journal of Vocational and Technical Education, 7(5), 40–53. Available online: https://academicjournals.org/journal/IJVTE/article-full-text/B567CD853548 (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Dey, A., & Rahman, M. H. A. (2023). Impact of social media-based brand community participation on brand image in Bangladesh: Mediating role of brand association and brand awareness. Global Journal of Management and Business Research, 22(3), 71–84. Available online: https://journalofbusiness.org/index.php/GJMBR/article/view/102778 (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- Doan, T. T. T. (2021). The effect of service quality on student loyalty and student satisfaction: An empirical study of universities in Vietnam. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics, and Business, 8(8), 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eger, L., Egerová, D., & Pisoňová, M. (2018). Assessment of school image. Center of Educational Policy Studies Journal, 8(2), 97–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elahinia, N., & Karami, M. (2019). The influence of service quality on Iranian students’ satisfaction, loyalty and WOM: A case study of north Cyprus. Journal of Management, Marketing and Logistics (JMML), 6(1), 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. (2024). Education and training monitor 2024—Comparative report, publications office of the European Union. European Commission. [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C. (1992). A national customer satisfaction barometer: The swedish experience. Journal of Marketing, 56(1), 6–21. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1252129 (accessed on 10 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Fuller, C. M., Simmering, M. J., Atinc, G., Atinc, Y., & Babin, B. J. (2016). Common methods variance detection in business research. Journal of Business Research, 69(8), 3192–3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, T., & Pinar, M. (2020). An empirical study of the dynamic relationships between the core and supporting brand equity dimensions in higher education. Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education, 13(3), 710–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenacre, L., Freeman, L., Cong, K., & Chapman, T. (2014). Understanding and predicting student word of mouth. International Journal of Educational Research, 64, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grönroos, C. (1984). A service quality model and its marketing implications. European Journal of Marketing, 18(4), 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T., Li, T., & Qi, Z. (2024). Perceived school service quality and vocational students’ learning satisfaction: Mediating role of conceptions of vocational education. PLoS ONE, 19(8), e0307392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2022). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (3rd ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, H. F. A., Ilias, A., Rahman, R. A., & Razak, M. Z. A. (2008). Service quality and student satisfaction: A case study at private higher education institutions. International Business Research, 1(3), 163–175. Available online: http://www.ccsenet.org/journal/index.php/ibr/article/view/982 (accessed on 4 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S., & Shamsudin, M. F. (2019). Measuring the effect of service quality and corporate image on student satisfaction and loyalty in higher learning institutes of technical and vocational education and training. International Journal of Engineering and Advanced Technology, 8(5-C), 533–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S., Shamsudin, M. F., Hasim, M. A., Mustapha, I., Jaafar, J., Adruthdin, K. F., Shukri, A., Karim, S., & Ahmad, R. (2019a). Mediating effect of corporate image and students’ satisfaction on the relationship between service quality and students’ loyalty in TVET HLIs. Asian Academy of Management Journal, 24(Supp. 1), 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S., Shamsudin, M. F., & Mustapha, I. (2019b). The effect of service quality and corporate image on student satisfaction and loyalty in TVET higher learning institutes (HLIs). Journal of Technical Education and Training, 11(4), 77–85. Available online: https://publisher.uthm.edu.my/ojs/index.php/JTET/article/view/3989 (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Haverila, M., Haverila, K., McLaughlin, C., & Arora, M. (2021). Towards a comprehensive student satisfaction model. The International Journal of Management Education, 19, 100558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helgesen, Ø., & Nesset, E. (2007). Images, satisfaction and antecedents: Drivers of student loyalty? A case study of a Norwegian university college. Corporate Reputation Review, 10(1), 38–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irpansyah, M. A., Chan, A., & Tresna, P. W. (2023). The role of brand on educational institution. Journal Samudra Ekonomi dan Bisnis, 14(2), 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isnawijayani, Wulandari, M., Helmi, S., Kartika, T., & Supardin, L. (2025). The relationship between brand association, brand awareness and brand image in improving perceived quality in the telecommunications company industry. Pakistan Journal of Life and Social Sciences, 23(1), 4661–4670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamaludin, J., & Sugiyanto, L. B. (2024). The effect of service quality and endorser credibility on purchase decision mediated by brand image (empirical study: Active students of jaya buana vocational high school in tangerang regency). Return: Study of Management Economic and Business, 3(8), 632–646. Available online: https://return.publikasikupublisher.com/index.php/return/issue/view/24 (accessed on 4 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Jiewanto, A., Laurens, C., & Nelloh, L. (2012). Influence of service quality, university image, and student satisfaction toward WOM intention: A case study on Universitas Pelita Harapan Surabaya. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences, 40, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kairat, K., Lee, S. J., & Jang, J. M. (2024). The determinants of recommendation intention and student satisfaction in private higher institutions: Empirical evidence from Kazakhstan. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K. L. (1993). Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. Journal of Marketing, 57(1), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S. K., & Jalees, T. (2016). Antecedents to brand image. Market Forces Research Journal, 11(2), 11–25. Available online: https://kiet.edu.pk/marketforces/index.php/marketforces/issue/view/43 (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Klomtooksing, W., & Sato, S. C. (2023). Factors affecting the brand image of international schools through parents’ perceptions in Bangkok, Thailand. Advance Knowledge for Executives, 2(4), 1–11. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4596239 (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Kock, N. (2015). Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. International Journal of e-Collaboration (IJeC), 11(4), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, W. B., Islam, M. A., & Mohamad, M. B. (2015). Antecedents of brand image: A conceptual model. Australian Journal of Business and Economic Studies, 1(1), 95–100. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/274065518_ANTECEDENTS_OF_BRAND_IMAGE_A_CONCEPTUAL_MODEL#fullTextFileContent (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Le, L. C. (2021). Factors affecting brand image: A case study of public universities in Ho Chi Minh city. Ilkogretim Online, 20(4), 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leninkumar, V. (2017). An investigation on the relationship between service quality and customer loyalty: A mediating role of customer satisfaction. Archives of Business Research, 5(5), 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lundahl, L., Arreman, I. E., Holm, A.-S., & Lundström, U. (2013). Educational marketization the Swedish way. Education Inquiry, 4(3), 497–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M., & Nasib, N. (2021). The effort to increase loyalty through brand image, brand trust, and satisfaction as intervening variables. Society, 9(1), 27–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, J. A., & Martínez, L. (2010). Some insights on conceptualizing and measuring service quality. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 17(1), 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesta, H. A. (2019). The impact of satisfaction on loyalty in higher education: The mediating role of university’s brand image. Advances in Economics, Business and Management Research, 64, 563–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ministry of Education and Science, Bulgaria. (2023). Strategic vision for the development of dual vocational education and training (dVET) in Bulgaria—2030. Available online: https://www.mon.bg/nfs/2023/10/strategy-dual_17102023.pdf (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Moslehpour, M., Chau, K. Y., Zheng, J., Hanjani, A. N., & Hoang, M. (2020). The mediating role of international student satisfaction in the relationship between higher education service quality and institutional reputation in Taiwan. International Journal of Engineering Business Management, 12, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourad, M., Ennew, C., & Kortam, W. (2011). Brand equity in higher education. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 29(4), 403–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesset, E., & Helgesen, Ø. (2009). Modelling and managing student loyalty: A study of a Norwegian University College. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 53(4), 327–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L. T. K., Lin, T. M. Y., & Lam, H. P. (2021). The role of co-creating value and its outcomes in higher education marketing. Sustainability, 13(12), 6724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, S. L., & Berliner, D. C. (2007). Collateral damage: How high-stakes testing corrupts America’s schools. Harvard Education Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nursetiani, A., & Wahyuni, S. (2024). Does service quality influence satisfaction and impact to word of mouth? A case study at Indonesian vocational high school. International Journal of Advanced Research, 12(07), 646–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R. L. (1999). Whence consumer loyalty? Journal of Marketing, 63, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. (2024, December 17). How are demographic changes affecting education systems? Education Indicators in Focus #87—December 2024. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/how-are-demographic-changes-affecting-education-systems_158d4c5c-en.html (accessed on 9 August 2025).

- Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V., & Berry, L. L. (1988). SERVQUAL: A multiple-item scale for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality. Journal of Retailing, 64(1), 12–40. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/7d007e04d78261295e5524f15bef6837/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=41988 (accessed on 4 July 2025).

- Perera, C. H., Nayak, R., & Nguyen, L. T. V. (2022). The impact of social media marketing and brand credibility on higher education institutes’ brand equity in emerging countries. Journal of Marketing Communications, 29(8), 770–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peruta, A., & Shields, A. B. (2016). Social media in higher education: Understanding how colleges and universities use Facebook. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 27(1), 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinar, M., Trapp, P., Girard, T., & Boyt, T. E. (2014). University brand equity: An empirical investigation of its dimensions. International Journal of Educational Management, 28(6), 616–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradana, N. R., & Nurali, N. (2020). Influence analyst brand image against student’s decision to choose dwija bhakti 2 jombang vocational school with word of mouth positiveas a moderating variable. SNEB: Seminar Nasional Ekonomi Dan Bisnis Dewantara, 2(1), 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richins, M. L. (1983). Negative word of mouth by dissatisfied customers: A pilot study. Journal of Marketing, 47, 68–78. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/235356549_Negative_word_of_mouth_by_dissatisfied_customers_A_pilot_study_Journal_of_Marketing#fullTextFileContent (accessed on 5 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Riezebos, H. J., Kist, B., & Kootstra, G. (2003). Brand management: A theoretical and practical approach. Financial Times Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas-Lamorena, Á. J., Del Barrio-García, S., & Alcántara-Pilar, J. M. (2022). A review of three decades of academic research on brand equity: A bibliometric approach using co-word analysis and bibliographic coupling. Journal of Business Research, 139, 1067–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusdi, M., & Ali, M. M. (2020). Influence of service quality and school image on satisfaction and its implications towards loyalty of students SMK PGRI 35 Jakarta. Dinasti International Journal of Digital Business Management, 2(1), 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M., Hair, J. F., Jr., Cheah, J.-H., Becker, J.-M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). How to specify, estimate, and validate higher-order constructs in PLS-SEM. Australasian Marketing Journal, 27(3), 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satria, H. W., & Hidayat, D. P. (2018). Does brand love and brand image have a strong impact on word of mouth? (Evidence from the indonesian vocational school). KnE Social Sciences, 3(11), 320–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwede, J., Heisler, D., & Harteis, C. (2025). Integrating practice-based learning into formal education: Stakeholder perspectives on the challenges of learning location cooperation (LLC) in Germany’s dual VET system. Social Sciences, 14(3), 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shmueli, G., Sarstedt, M., Hair, J. F., Cheah, J.-H., Ting, H., Vaithilingam, S., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). Predictive model assessment in PLS-SEM: Guidelines for using PLSpredict. European Journal of Marketing, 53(11), 2322–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sholihah, C. (2023). Branding image management in improving the competitiveness of early children’s education in the Society 5.0 ERA. Proceeding of International Conference on Education, Society and Humanity, 1(1), 925–933. Available online: https://ejournal.unuja.ac.id/index.php/icesh/article/view/5990 (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Sintani, L. (2020). School characteristics, skill competency, school images and of the parents social classes in affecting student decisions to choose middle vocational schools at vocational schools in Palangka Raya Central Kalimantan. Jurnal Wawasan Manajemen, 8(1), 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, P., & Wong, H. Y. (2019). How Service Quality Affects University Brand Performance, Brand Image, and Behavioral Intention: The Mediating Effects of Satisfaction and Trust and Moderating Roles of Gender and Study Mode. Journal of Brand Management, 26, 332–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, A. H., & Duc, T. T. (2022). Impact of brand identity components on university brand image in Ho Chi Minh city. Journal of Positive School Psychology, 6(2), 5903–5915. Available online: https://journalppw.com/index.php/jpsp/article/view/3544 (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. (2021). Global education monitoring report—Non-state actors in education: Who chooses? who loses? UNESCO. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, U., & Mokhtar, S. S. M. (2016). Analysis of service quality, university image and student satisfaction on student loyalty in higher education in Nigeria. International Business Management, 10(12), 2490–2502. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/309119075_Analysis_of_service_quality_university_image_and_student_satisfaction_on_student_loyalty_in_higher_education_in_Nigeria/citations (accessed on 4 July 2025).

- Verger, A., Fontdevila, C., & Zancajo, A. (2016). The privatization of education: A political economy of global education reform. Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Waslander, S., Pater, C., & van der Weide, M. (2010). Markets in education: An analytical review of empirical research on empirical resesarch on market mechanisms in education. OECD Education Working Papers, No. 52. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasa, N. N. K., Giantari, I. G. A. K., Rahmayanti, P. L. D., & Tirtayani, I. G. A. (2021). Antecedent of WOM and its implicatins on the brand image of the higher education institution in Bali. Jurnal Dinamika Manajemen, 12(2), 245–261. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/377403321_Antecedent_of_WOM_and_Its_Implications_on_The_Brand_Image_of_The_Higher_Education_Institution_in_Bali (accessed on 4 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Zeqiri, J., Dania, T. R., Adriana, L.-T. D., Gagica, K., & Gleason, K. (2023). The impact of e-service quality on word of mouth: A higher education context. The International Journal of Management Education, 21(3), 100850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Constructs and Measurement Items | Loadings |

|---|---|

| (LEQ) Low Entry Qualification (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.715, CR = 0.837, AVE = 0.633) | |

| LEQ1. Vocational students have low learning abilities. | 0.692 |

| LEQ2. My school gives access to all secondary school students. | 0.836 |

| LEQ3. My school has low and flexible entry requirements. | 0.849 |

| (TFE) Training Facilities and Equipment (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.880, CR = 0.944, AVE = 0.893) | |

| TFE1. The company where I do my vocational training has proper equipment and the latest technology. | 0.945 |

| TFE2. The company where I train has enough space for good training. | 0.946 |

| (MC) Mentors Credibility (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.905, CR = 0.941, AVE = 0.841) | |

| MC1. Helpful mentors. | 0.910 |

| MC2. Experienced mentors. | 0.926 |

| MC3. Qualified mentors. | 0.915 |

| (CJP) Career and Job Potential (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.870, CR = 0.911, AVE = 0.719) | |

| CJP1. The dVET provides students with strong practical skills. | 0.818 |

| CJP2. The dVET enables the integration of academic knowledge and technical skills. | 0.855 |

| CJP3. The dVET offers a wide range of career selections for graduates. | 0.861 |

| CJP4. The dVET system prepares students to meet the needs of the nation. | 0.856 |

| (CU) Curriculum (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.725, CR = 0.879, AVE = 0.784) | |

| CU1. The theory we learn at school is closely connected to our practical training. | 0.875 |

| CU2. My school maintains strong connections with various industries. | 0.896 |

| (RVQ) Recognition of Vocational Qualification (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.830, CR = 0.921, AVE = 0.854) | |

| RVQ1. The dVET qualification is recognized by many private companies in Bulgaria. | 0.934 |

| RVQ2. The dVET qualification is recognized by many foreign companies. | 0.915 |

| (SOF) Soft skills (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.784, CR = 0.902, AVE = 0.822) | |

| SOF6. DVET graduates have communication skills. | 0.918 |

| SOF7. DVET graduates have leadership skills. | 0.895 |

| (TAN) Tangibility (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.841, CR = 0.883, AVE = 0.558) | |

| TAN1. The learning material we study is modern and up to date. | 0.758 |

| TAN2. Number of vocational programs offered. | 0.721 |

| TAN3. Adequacy of computers provided in the classrooms for students. | 0.741 |

| TAN5. Degree to which classrooms and study rooms are comfortable. | 0.796 |

| TAN6. Access to the Internet/e-mail. | 0.690 |

| TAN7. Overall cleanliness. | 0.771 |

| (ASSR) Assurance (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.889, CR = 0.931, AVE = 0.818) | |

| ASSR1. Friendly and courteous teachers. | 0.894 |

| ASSR2. The teachers are innovative. | 0.910 |

| ASSR3. Communication skills: lessons are well taught by the teachers in my vocational secondary school. | 0.910 |

| (REL) Reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.736, CR = 0.883, AVE = 0.791) | |

| REL1. Teachers are punctual and rarely cancel classes. | 0.893 |

| REL3. Teachers’ sincere interest in solving the student’s problem | 0.886 |

| (RES) Responsiveness (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.823, CR = 0.894, AVE = 0.738) | |

| RES1. Teachers’ capacity to solve problems when they arise. | 0.878 |

| RES2. Staff’s capacity to solve problems when they arise. | 0.859 |

| RES3. I seldom get the “run-around” when seeking information from this school. | 0.840 |

| (BA) Brand Association (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.817, CR = 0.916, AVE = 0.845) | |

| BA1. My school offers many opportunities for vocational training. | 0.925 |

| BA3. My school organizes events related to the presentation of various professions and employers. | 0.914 |

| (SL) Student Loyalty (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.859, CR = 0.934, AVE = 0.876) | |

| SL1. There is a high probability that I would recommend this school to my friends or acquaintances. | 0.938 |

| SL2. If I had to start over, there is a high chance I would choose the same school again. | 0.934 |

| (BR) Brand Relevance (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.722, CR = 0.878, AVE = 0.782) | |

| BR1. My school looks modern and up to date. | 0.874 |

| BR2. My school provides learning value tailored to my needs. | 0.894 |

| (SS) Student Satisfaction (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.939, CR = 0.970, AVE = 0.942) | |

| SS1. I am satisfied with my decision to attend this school. | 0.973 |

| SS2. I am happy with my decision to enroll in this school. | 0.968 |

| (BI) Brand Image (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.757, CR = 0.858, AVE = 0.669) | |

| BI1. The name of the school is well known in the Plovdiv region. | 0.796 |

| BI2. The name of the school is associated with high-quality teaching. | 0.789 |

| BI3. My school has a strong brand image. | 0.868 |

| (WOM) Word of mouth (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.831, CR = 0.898, AVE = 0.747) | |

| WOM1. I always speak well of this school to people. | 0.894 |

| WOM2. I usually talk about this school with my friends. | 0.787 |

| WOM3. I am honored to tell people that I am studying in this school. | 0.906 |

| BA | LEQ | TFE | MC | CJP | CU | RVQ | SOF | BI | SL | TAN | ASSR | REL | RES | BR | SS | WOM | |

| BA | 0.919 | 0.203 | 0.560 | 0.528 | 0.704 | 0.798 | 0.562 | 0.594 | 0.658 | 0.656 | 0.616 | 0.566 | 0.600 | 0.586 | 0.678 | 0.551 | 0.812 |

| LEQ | 0.165 | 0.796 | 0.290 | 0.206 | 0.203 | 0.251 | 0.150 | 0.176 | 0.357 | 0.197 | 0.385 | 0.150 | 0.170 | 0.233 | 0.244 | 0.203 | 0.256 |

| TFE | 0.475 | 0.253 | 0.945 | 0.841 | 0.720 | 0.634 | 0.528 | 0.516 | 0.517 | 0.453 | 0.570 | 0.457 | 0.503 | 0.449 | 0.477 | 0.484 | 0.574 |

| MC | 0.454 | 0.184 | 0.752 | 0.917 | 0.693 | 0.583 | 0.474 | 0.476 | 0.498 | 0.423 | 0.534 | 0.445 | 0.535 | 0.420 | 0.466 | 0.426 | 0.526 |

| CJP | 0.596 | 0.178 | 0.632 | 0.615 | 0.848 | 0.837 | 0.543 | 0.549 | 0.583 | 0.557 | 0.657 | 0.544 | 0.607 | 0.580 | 0.589 | 0.598 | 0.720 |

| CU | 0.616 | 0.193 | 0.508 | 0.474 | 0.668 | 0.885 | 0.635 | 0.707 | 0.719 | 0.633 | 0.734 | 0.642 | 0.663 | 0.684 | 0.757 | 0.629 | 0.797 |

| RVQ | 0.463 | 0.117 | 0.451 | 0.411 | 0.463 | 0.493 | 0.924 | 0.838 | 0.584 | 0.493 | 0.540 | 0.462 | 0.493 | 0.475 | 0.523 | 0.410 | 0.639 |

| SOF | 0.475 | 0.146 | 0.430 | 0.404 | 0.456 | 0.533 | 0.678 | 0.907 | 0.636 | 0.530 | 0.620 | 0.511 | 0.582 | 0.520 | 0.579 | 0.443 | 0.657 |

| BI | 0.534 | 0.263 | 0.429 | 0.420 | 0.494 | 0.552 | 0.482 | 0.506 | 0.818 | 0.694 | 0.711 | 0.563 | 0.723 | 0.610 | 0.740 | 0.561 | 0.770 |

| SL | 0.549 | 0.169 | 0.394 | 0.374 | 0.482 | 0.499 | 0.415 | 0.436 | 0.578 | 0.936 | 0.578 | 0.545 | 0.629 | 0.603 | 0.649 | 0.657 | 0.801 |

| TAN | 0.513 | 0.307 | 0.494 | 0.470 | 0.566 | 0.575 | 0.453 | 0.507 | 0.581 | 0.495 | 0.747 | 0.730 | 0.784 | 0.750 | 0.867 | 0.589 | 0.715 |

| ASSR | 0.483 | 0.131 | 0.404 | 0.399 | 0.479 | 0.517 | 0.396 | 0.429 | 0.484 | 0.477 | 0.632 | 0.905 | 0.833 | 0.754 | 0.735 | 0.642 | 0.684 |

| REL | 0.465 | 0.136 | 0.405 | 0.437 | 0.487 | 0.485 | 0.388 | 0.444 | 0.554 | 0.500 | 0.617 | 0.674 | 0.890 | 0.791 | 0.807 | 0.635 | 0.741 |

| RES | 0.481 | 0.188 | 0.381 | 0.363 | 0.491 | 0.529 | 0.391 | 0.417 | 0.497 | 0.509 | 0.624 | 0.648 | 0.619 | 0.859 | 0.789 | 0.593 | 0.687 |

| BR | 0.522 | 0.184 | 0.380 | 0.377 | 0.468 | 0.549 | 0.406 | 0.437 | 0.563 | 0.511 | 0.678 | 0.591 | 0.591 | 0.613 | 0.884 | 0.652 | 0.726 |

| SS | 0.483 | 0.172 | 0.441 | 0.394 | 0.542 | 0.520 | 0.364 | 0.381 | 0.493 | 0.592 | 0.529 | 0.588 | 0.529 | 0.525 | 0.538 | 0.971 | 0.683 |

| WOM | 0.674 | 0.208 | 0.495 | 0.460 | 0.619 | 0.626 | 0.527 | 0.531 | 0.637 | 0.688 | 0.608 | 0.598 | 0.587 | 0.573 | 0.568 | 0.615 | 0.864 |

| Indicators | VIF Values | Indicators | VIF Values | Indicators | VIF Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BA1 | 1.911 | CJP2 | 2.280 | ASSR2 | 2.720 |

| BA2 | 1.911 | CJP3 | 2.243 | ASSR3 | 2.638 |

| BR1 | 1.468 | CJP4 | 2.085 | REL1 | 1.514 |

| BR2 | 1.468 | CU1 | 1.477 | REL2 | 1.514 |

| BI1 | 1.470 | CU2 | 1.477 | RES1 | 1.926 |

| BI2 | 1.562 | RVQ1 | 2.010 | RES2 | 1.986 |

| BI3 | 1.554 | RVQ2 | 2.010 | RES3 | 1.707 |

| LEQ1 | 1.309 | SOF1 | 1.712 | SL1 | 2.309 |

| LEQ2 | 1.553 | SOF2 | 1.712 | SL2 | 2.309 |

| LEQ3 | 1.433 | TAN1 | 1.848 | SS1 | 4.587 |

| TFE1 | 2.620 | TAN2 | 1.890 | SS2 | 4.587 |

| TFE2 | 2.620 | TAN3 | 1.681 | WOM1 | 2.201 |

| MC1 | 2.693 | TAN4 | 2.176 | WOM2 | 1.627 |

| MC2 | 3.340 | TAN5 | 1.673 | WOM3 | 2.252 |

| MC3 | 2.937 | TAN6 | 1.744 | ||

| CJP1 | 1.901 | ASSR1 | 2.436 |

| Hypotheses | β-Value | 2.5% CI | 97.5% CI | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1: Brand Associations → Brand Image | 0.332 | 0.247 | 0.418 | Supported |

| H2: Brand Relevance → Brand Image | 0.391 | 0.310 | 0.471 | Supported |

| H3: Brand Image → Image of dVET | 0.627 | 0.570 | 0.682 | Supported |

| H4: Image of dVET → Student Satisfaction | 0.253 | 0.144 | 0.366 | Supported |

| H5: Service Quality → Student Satisfaction | 0.463 | 0.356 | 0.559 | Supported |

| H6a: Student Satisfaction → WOM | 0.616 | 0.549 | 0.679 | Supported |

| H6b: Student Satisfaction → Student Loyalty | 0.592 | 0.525 | 0.656 | Supported |

| Hypotheses | β-Value | 2.5% CI | 97.5% CI | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H7a: Brand Associations → Brand Image → Image of dVET | 0.208 | 0.149 | 0.273 | Supported |

| H7b: Brand Relevance → Brand Image → Image of dVET | 0.245 | 0.191 | 0.304 | Supported |

| H8: Brand Image → Image of dVET → Student Satisfaction | 0.159 | 0.089 | 0.236 | Supported |

| H9a: Image of dVET → Student Satisfaction → WOM Communication | 0.156 | 0.084 | 0.235 | Supported |

| H9b: Image of dVET → Student Satisfaction → Student Loyalty | 0.150 | 0.082 | 0.225 | Supported |

| H10a: Service Quality → Student Satisfaction → WOM Communication | 0.285 | 0.214 | 0.352 | Supported |

| H10b: Service Quality → Student Satisfaction → Student Loyalty | 0.274 | 0.207 | 0.336 | Supported |

| Structural Path | VIF Values | Structural Path | VIF Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| BA → BI | 1.374 | SQ → SS | 1.911 |

| BI → IDVET | 1.000 | SS → SL | 1.000 |

| BR → BI | 1.374 | SS → WOM | 1.000 |

| IDVET → SS | 1.911 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dimitrova, T.; Ilieva, I.; Toncheva, V. Determinants of Student Loyalty and Word of Mouth in Dual VET Secondary Schools in Bulgaria. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 348. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15090348

Dimitrova T, Ilieva I, Toncheva V. Determinants of Student Loyalty and Word of Mouth in Dual VET Secondary Schools in Bulgaria. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(9):348. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15090348

Chicago/Turabian StyleDimitrova, Teofana, Iliana Ilieva, and Valeria Toncheva. 2025. "Determinants of Student Loyalty and Word of Mouth in Dual VET Secondary Schools in Bulgaria" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 9: 348. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15090348

APA StyleDimitrova, T., Ilieva, I., & Toncheva, V. (2025). Determinants of Student Loyalty and Word of Mouth in Dual VET Secondary Schools in Bulgaria. Administrative Sciences, 15(9), 348. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15090348