Abstract

Healthcare is a complex sociotechnical system consisting of several groups of people interacting with each other to provide patient care. Employee commitment, empowerment, and continuous learning are crucial factors in this system. This study aims to investigate the relationship between dialogue and inquiry, a significant component of individual learning, and employee commitment in the healthcare industry. Based on organizational learning theory (OLT) and organizational commitment theory (OCT), a conceptual model was developed, and hypotheses were tested by collecting data from 346 employees working in a multi-specialty hospital in southern India. After checking the psychometric properties of the survey instrument, structural equation modeling was used to analyze data. The results indicate that (i) dialogue and inquiry positively predicts empowerment and employee commitment, (ii) empowerment is a precursor to employee commitment, and (iii) empowerment mediates the relationship between dialogue and inquiry and employee commitment. The results also support the moderating effect of system connection in the relationship between dialogue inquiry and empowerment. Further, strategic leadership interacts with empowerment to positively influence employee commitment. The findings provide valuable insights to the administrators and decision-makers in the healthcare industry for enhancing employee commitment necessary to provide low-cost and high-quality patient care. The conceptual model is first of its kind with regard to healthcare industry in India and hence makes a pivotal contribution to the advancement of literature on healthcare.

1. Introduction

The success of healthcare organizations largely hinges on the commitment of employees to provide high-quality service to the patients (S. Ahmed et al., 2018; Dawood-Khan et al., 2024; Janicijevic et al., 2013; Rod & Ashill, 2010). Service quality and patient satisfaction in a hospital largely depends on the efficiency of healthcare workers (physicians, nurses, and administrative staff) in meeting the expected standards of care and service (Janicijevic et al., 2013; Mansoor et al., 2025). Administrators in healthcare organizations are trying to find ways of providing cost-effective healthcare to patients, and one of the strategies is to increase the commitment of healthcare staff (doctors, nurses, and ancillary service providers) (Shreffler et al., 2020). Increased pressure necessitates healthcare workers to continually engage in learning to meet the ever-increasing and changing demands of customers (i.e., patients). To provide quality service to the patients, it is vital that the employees should exhibit higher levels of affective, continuance, and normative commitment. This paper is aimed at unraveling the antecedents to the employee commitment.

Using two theoretical platforms—organizational learning theory (OLT) (Argyris & Schon, 1978) and organizational commitment theory (OCT) (J. P. Meyer et al., 1993)—this research unfolds the relationships between five variables: dialogue and inquiry, empowerment, system connection, strategic leadership, and employee commitment. Dialogue and inquiry, a critical component of individual learning, refers to how individuals share knowledge through discussions, debates, and conversations (Marsick & Watkins, 2003). Empowerment is the degree to which administrators provide authority and power to the employees to make decisions and give access to the necessary resources (Haas, 2010). Empowerment is related to sanctioning access to resources to the employees for completing challenging assignments and contributing to the organization’s vision (Marsick & Watkins, 2003). System connectivity refers to the extent to which the employees (physicians, nurses, and therapists) connect to each other and bring customers’ views to the decision-making platform. Most importantly, system connection ensures how these groups of people combine different perspectives, skills, and abilities to deliver quality care to diverse customers. Strategic leadership refers to the extent to which leaders instill confidence in employees and exhibit individualized consideration and provide inspirational motivation to provide excellent service to the customers [i.e., patients in healthcare organizations]. The dependent variable—organizational commitment refers to the psychological state consisting of three components: affective, normative, and continuance commitment. Affective commitment refers to the degree to which employees exhibit their desire to maintain employment in organization. Continuous commitment refers to the degree to which an employee feels the need to maintain employment. Normative commitment refers to the degree to which an employee feels an obligation to maintain employment (J. Meyer & Allen, 1997).

Though a sizable amount of research focused on antecedents (e.g., job satisfaction) to employee commitment (Aghaei et al., 2012; Allen & Meyer, 1990; Klein et al., 2012; Rose et al., 2009; Mercurio, 2015; Solinger et al., 2008), relatively few studies focused on learning as a precursor to commitment (S. Ahmed et al., 2018; Hendri, 2019). Especially in the context of healthcare organizations, it is predicted that committed employees are more likely to provide better service to patients (Somaskandan et al., 2022). Further, when healthcare employees are encouraged to participate in strategic decision-making, resulting in high empowerment, they are more likely to show their willingness to stay with the organization and contribute to its success in providing better service to the patients (Nayak et al., 2018).

It is important to note that the potential impact of individual learning, organizational learning, and strategic leadership on employee commitment, particularly in the context of healthcare organizations, has yet to receive much attention from scholars. To bridge the gap, this study attempts to investigate the effect of learning through dialogues and inquiry on empowerment and commitment. The findings of this research could have significant implications for healthcare management and organizational behavior. This research is aimed at answering the following research questions (RQs):

RQ1: How dialogue and inquiry (individual learning) influences empowerment and employee commitment in healthcare organizations

RQ2: How empowerment mediates the relationship between dialogue and inquiry and employee commitment in healthcare organizations

RQ3: How system connection moderates the relationship between dialogue and inquiry and empowerment

RQ4: How strategic leadership moderates the relationship between empowerment and employee commitment in healthcare organizations

Literature Review

As the recently hit global pandemic has increased the reliance of patients on the healthcare industry, it is essential to explore ways to provide quality care to patients in an efficient manner (Bhojak et al., 2022; Capone et al., 2023; Dawood-Khan et al., 2024; Eapen et al., 2022a). In India, the global pandemic has adversely affected all individuals and families, pushing several people below the poverty line and imposing several challenges to make healthcare costs affordable (Eapen et al., 2022b; Gopalan & Misra, 2020; Shoaib et al., 2022). The post-pandemic period resulted in an escalation of the cost of medical treatments and a shortage of resources (physicians, doctors, nurses, and administrative staff) to meet the ever-increasing demands of patients. For example, a recently conducted systematic literature review revealed that healthcare organizations face severe challenges of high cost and low efficiency in health services (Mendes & França, 2024) and suggest commitment by employees and efficiency management team as the potential solution. Studies conducted before the pandemic also stressed the importance of employees’ commitment as necessary to provide quality services in healthcare organizations (S. Ahmed et al., 2018; Nayak et al., 2018). In a study administered in 15 different hospitals in Malaysia to 335 hospital staff (doctors, nurses, pharmacists, and medical laboratory technicians), it was found that top management commitment has been positively associated with the quality of services provided to the patients (S. Ahmed et al., 2018).

In a study conducted on 279 employees in private healthcare units in India, Nayak et al. (2018) found that empowerment and commitment are crucial indicators of successful performance. However, the literature is rife with studies on lean management in healthcare organizations, which focused on reducing waste and increasing efficiency in patient care (Kallal et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2021; Mahmoud et al., 2021; Tlapa et al., 2022; Wagner et al., 2022). Few studies focused on how learning through dialogues and inquiry and knowledge sharing and empowerment affect employee commitment, which is a precursor for providing quality service to patients. Some scholars emphasize the role of top management commitment to achieving patient satisfaction (Gayoso-Rey et al., 2020) and suggest that organizations need to understand the dynamics of their organizations to see how healthcare professionals provide better service.

This research makes five significant contributions to the advancement of organizational learning (OLT) and organizational commitment theory (OCT) and practice in healthcare sector. First, this study underscores the importance of dialogue and inquiry among stakeholders in ensuring both employee commitment and empowerment. Second, this research provides empirical evidence that empowerment acts as a mediator in the relationship between dialogue and inquiry and employee commitment. In healthcare organizations, dialogue and inquiry [discussions and debates] have an indirect effect on employee commitment through empowerment. Third, this study highlights the significance of system connection (i.e., how various stakeholders are connected to each other) strengthens the positive effect of dialogue and inquiry on employee empowerment. Fourth, this study emphasizes the importance of strategic leadership in strengthening the positive effect of empowerment on employee commitment. Fifth, the conceptual model developed and tested in the context of healthcare organizations is first of its kind to the best of our knowledge makes a pivotal contribution to expand theoretical foundations of OLT and OCT.

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Development

The theoretical underpinnings for this study are organizational learning theory (OLT) (Argyris & Schon, 1978; Senge, 1990) and organizational commitment theory (OCT) (J. P. Meyer et al., 1993; Mowday et al., 1979; O’Reilly & Chatman, 1986). The basic tenet of OLT is that employees engage in continuous learning through information sharing at the individual, group, and organizational levels. To cope with the increasing patient demands, administrators, nurses, and doctors share information and knowledge acquisition through dialogue and inquiry. According to OLT, organizations must create an environment for employees to learn to complete complex tasks requiring problem-solving skills. From the OLT, we incorporated the components of individual learning (dialogue and inquiry with peers and supervisors) and organizational learning (system connection, strategic leadership, and empowerment) to explain the effect of these on employee commitment. To meet the challenges, organizations “continuously acquire, process, and disseminate throughout the organization knowledge about markets, products, technologies, and business processes” (Slater & Narver, 1995, p. 71), and healthcare organizations are no exception.

In this study, we also used the three-dimensional construct of employee commitment (affective, normative, and continuance) from the OCT. Extant research reported positive outcomes of employee commitment (lower turnover intention, lower absenteeism, and increased organizational citizenship behavior) (Allen & Meyer, 1990; Griffeth et al., 2000). In healthcare organizations, employee commitment results in increased patient satisfaction and service quality (Perreira et al., 2018; Somaskandan et al., 2022).

2.1. Hypotheses Development

2.1.1. Dialogue and Inquiry and Employee Commitment

One important component of learning is dialogue and inquiry through which employees in organizations share knowledge. In general, discussions, debates, and conversations between employees result in acquiring new knowledge that helps in making decisions (Marsick & Watkins, 2003). There is abundant empirical evidence in support of the positive effect of dialogue and inquiry (individual learning) on employee commitment (Battistelli et al., 2019; Goh & Gregory, 1997; Kamali et al., 2017; J. P. Meyer et al., 2002; Naim & Lenka, 2020; Ryu & Moon, 2019; Saadat & Saadat, 2016). In a study conducted on 510 employees in the information technology sector in India, Malik and Garg (2017) found that dialogue and inquiry and knowledge sharing positively affect affective commitment. Similarly, in a relatively recent study on administrative staff working in public universities, Annan-Prah et al. (2023) found that continuous learning and dialogue and inquiry positively impacted performance. Based on the theoretical underpinning of OLT, we offer the following hypothesis.

H1.

Dialogue and inquiry positively predict employee commitment.

2.1.2. Dialogue and Inquiry and Empowerment

When employees engage in continuous learning and knowledge sharing through dialogue and inquiry, administrators invite them to the platform of strategic decision-making. Empowerment is reflected when administrators recognize people for taking initiative and accepting challenging assignments (Hanafy et al., 2025; Shin & Shin, 2025). Empowerment is related to sanctioning access to resources to the employees for completing challenging assignments and contributing to the organization’s vision (Marsick & Watkins, 2003). Some scholars in the recent past found that dialogue and inquiry promote mutual empowerment and increase the therapeutic practice in nurse education (Pearson et al., 2021). In a study of 101 different hospitals, Metcalf et al. (2018) found that employee empowerment is crucial in improving the quality of patient services and reducing the cost associated with care. Several researchers documented that empowerment is necessary for performing their jobs meaningfully, and administrators provide support, information, and collaboration and give access to the resources (Lawler, 1994; Paradis et al., 2014). Thus, we offer the following hypothesis based on prior empirical evidence and logic.

H2.

Dialogue and inquiry positively predict empowerment.

2.1.3. Empowerment and Employee Commitment

As pointed out by Haas (2010), empowerment is the degree to which administrators provide authority and power to the employees to make decisions and give access to the necessary resources. Giving decision-making power to the employees or inviting the employees to a strategic decision-making process results in the decentralization of authority and power in organizations. Empowered employees enrich their experience and assume responsibility for performing given tasks effectively (Dainty et al., 2002; Chen et al., 2007; Nayak et al., 2018). The literature review reveals two types of empowerment: structural and psychological (Mathieu et al., 2006). Structural empowerment stems from top management, where employees are assigned to higher levels of jobs and are promoted to higher levels (Mills & Ungson, 2003). In contrast, psychological empowerment is related to the intrinsic motivation of individuals experienced through cognitions (self-determination, competence, impact, and meaningful work) (Spreitzer, 1995).

Previous studies have consistently shown that empowerment, whether structural or psychological, is a key precursor to employee commitment (Bhatnagar, 2007; DeCicco et al., 2006; Huang et al., 2006; Yang et al., 2014). In a recent study conducted in Indian retail sector, Bhardwaj et al. (2025) found positive association of empowerment with employee commitment. Empowerment motivates employees to invest their energy in completing tasks, as they take on responsibility, authority, and power, which in turn binds them to the organization (Janssen, 2004). When employees are encouraged to participate in all activities within the organization, they are more likely to demonstrate their commitment to staying with the organization (A. O. Ahmed et al., 2025). Furthermore, the process of empowerment often leads employees to invest a significant amount of time and energy in acquiring job-specific skills that cannot be easily transferred to other firms. This can create a sense of comfort and loyalty, making employees more likely to continue with their present organization (J. P. Meyer et al., 1993; Mowday et al., 1979; Somaskandan et al., 2022).

H3.

Empowerment is significantly and positively related to employee commitment.

2.1.4. Empowerment as a Mediator

While the direct effect of dialogue and inquiry on employee commitment is understandable, as explained above in Hypothesis 1, we argue that the benefits of dialogue and inquiry may also be routed through empowerment. When employees engage in discussions and dialogues with other members of the organization, they tend to expand their horizons of knowledge, which motivates administrators to give them additional responsibilities and access to the resources to complete assigned tasks. Further, as documented in a large study conducted on 1283 nurses working in public and private hospitals in Australia, empowerment was a significant predictor of affective commitment (Brunetto et al., 2011). While the studies on empowerment as a moderator are scant, in a recent study conducted on 389 working nurses in India (public and private hospitals operating in Punjab state), researchers found that psychological empowerment mediated the relationship between structural empowerment and employee commitment (Aggarwal et al., 2018). We offer the following exploratory mediation hypothesis based on the direct relationships between dialogue and inquiry, empowerment, and employee commitment.

H4.

Empowerment mediates the relationship between dialogue and inquiry and employee commitment.

2.1.5. System Connection as a Moderator

While in the manufacturing industry, total quality management (TQM) is widely practiced, in the healthcare industry, the way in which quality care for patients is maintained is different. Unlike manufacturing, healthcare organizations are considered unique and complex service units that follow a sociotechnical systems approach. In other words, the typical organizational structure of healthcare organizations consists of physicians, nurses, administrative and support staff, and patient care initiatives that require sociotechnical system thinking. Healthcare leaders, while striving to reduce costs and maintain high-quality service, are entrusted with the task of a patient-centered approach, which requires systems connection (Zhao et al., 2007). While manufacturing industries focus on new technological inventions and automation, healthcare service providers improve service rendering to patients because it is more of a life-or-death struggle (Boyer et al., 2012). In essence, both soft and hard skills are required by the hospital staff (doctors, nurses, and support staff). As pointed out by Effken (2002), healthcare organizations are represented by a complex and dynamic sociotechnical system where groups of people (physicians, nurses, and therapists) combine different perspectives, skills, and abilities to deliver quality care to diverse customers. System connection is vital to keep abreast of changes in the environment and changes in the requirements of patients (Carayon et al., 2011; Stoller, 2014). In this study, we argue that system connectivity (i.e., the extent to which employees bring customers’ views to the decision-making platform) strengthens the positive effect of dialogue and inquiry on empowerment. Based on the above arguments, we offer the following moderation hypothesis.

H5.

System connection positively moderates between dialogue and inquiry and empowerment such that at higher (lower) levels of system connectivity, the relationship between dialogue and inquiry and empowerment becomes stronger (weaker).

2.1.6. Strategic Leadership as a Moderator

In healthcare organizations, leadership plays a significant role in providing high-quality service to patients (Awais-E-Yazdan et al., 2023; Gözükara et al., 2018; Mendes & França, 2024). Nearly two decades back, researchers in a study conducted on 227 employees and managers in information technology and banking in Lebanon demonstrated that strategic leadership and empowerment are crucial elements in a learning organization (Jamali et al., 2009). In a recently conducted study on 605 (348 nurses, 114 physicians, and 143 other health professionals) respondents in the public healthcare sector in Cyprus, researchers documented that strategic leadership by top management team resulted in increasing employee engagement and commitment to providing service to patients (Giallouros et al., 2023). A recent study on healthcare organizations, Dahleez et al. (2025) found that strategic leadership plays a pivotal role in enhancing employee engagement, which is a precursor to commitment. Thus, while the direct effects of strategic leadership on employee engagement and commitment have been documented, we propose to study the moderating effect of strategic leadership in strengthening the positive impact of empowerment on employee commitment. Since none of the previous studies explored the multiplicative effect of empowerment and strategic leadership in influencing employee commitment, we offer the following exploratory moderation hypothesis.

H6.

Strategic leadership positively moderates between empowerment and employee commitment such that at higher (lower) levels of strategic leadership, the relationship between empowerment and employee commitment becomes stronger (weaker).

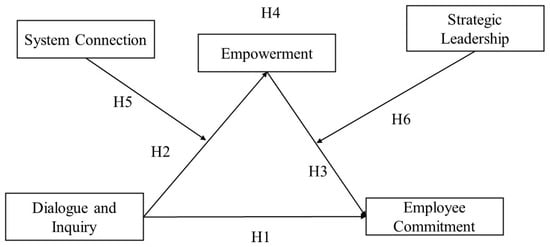

Conceptual model is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The conceptual model.

3. Method

3.1. Ethics Statement

Prior to starting the survey, participants were informed of the study’s aims/objectives and the right to refuse participation or withdraw from the study at any time. The authors confirm that this study adheres to the relevant ethical guidelines for human subjects and that the anonymity and confidentiality of the participants were maintained throughout the study.

3.2. Sample

This research aims to explore the antecedents of service quality in healthcare organizations. The role of learning through dialogue and inquiry and the level of empowerment and employee commitment are examined. Therefore, we collected data from employees from a healthcare organization. We collected data from a multi-specialty hospital in Bangalore (Karnataka state in southern India). A carefully crafted survey was prepared, and after conducting a pilot study involving 50 respondents, we distributed the surveys to nurses, doctors, and administrators in a multi-specialty hospital in Karnataka state of India. [Because of privacy we did not mention the name of the hospital]. We explained to the respondents that the survey was purely for academic purposes and that anonymity of the results would be maintained. Using systematic sampling, we distributed a survey to 500 employees and received 354 surveys (70.8% response rate). According to Krejcie and Morgan (1970), when population is under 1000, the required minimum sample size is 287. Therefore, our sample of 346 meets the criteria of minimum sample size. We found 8 incomplete surveys and included 346 surveys in the analysis. We checked non-response bias by comparing the first 75 respondents with the last 75 respondents and found no statistically significant differences between these two groups (Armstrong & Overton, 1977).

3.3. Demographic Profile of the Respondents

The respondents consist of 101 (29.2%) female and 245 (71.8%) male employees. The demographic profile of respondents is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic profile of respondents.

3.4. Measures

All five constructs in this research were measured using Likert-type five-point scale (“1” = strongly disagree; “5” = strongly agree). Four of the constructs—dialogue and inquiry, empowerment, system connection, and strategic leadership—were adapted from Dimensions of the Learning Organization Questionnaire (DLOQ) developed by Marsick and Watkins (2003). Dialogue and inquiry was measured with six items (α = 0.82), and the sample items read as, “In my organization, people give open and honest feedback to each other” and “In my organization, people listen to others’ views before speaking.” Empowerment was measured with six items (α = 0.85), and the sample items read as, “My organization recognizes people for taking initiative” and “My organization gives people choices in their work assignments.” System connection was measured with six items (α = 0.83), and the sample items read as, “My organization encourages everyone to bring the customers’ views into the decision-making process” and “My organization considers the impact of decisions on employee morale.” Strategic leadership was measured with six items (α = 0.86), and the sample items read as, “In my organization, leaders mentor and coach those they lead” and “In my organization, leaders continually look for opportunities to learn.” Employee commitment was measured with eight items (α = 0.86) using scale developed by J. Meyer and Allen (1997). The sample items read as, “I would be very happy to spend the rest of my career with this organization (affective commitment),” “It would be very hard for me to leave my organization right now, even if I wanted to (continuance commitment),” and “If I got another offer for a better job elsewhere, I would not feel it was right to leave my organization (normative commitment).”

4. Analysis and Findings

4.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

Following the recommendations of Anderson and Gerbing (1988), we checked measurement model first before testing the structural model. We used structural equation modeling (LISREL package), conducted confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), and presented the results in Table 2.

Table 2.

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA).

The factor loadings of most of the indicators were well above 0.70, except for four indicators, which ranged from 0.65 and 0.70. The reliability coefficient Cronbach’s alpha for all the constructs were over the acceptable level of 0.70 (ranged between 0.82 and 0.86), thus establishing internal reliability over 0.70. We made a comparison of various measurement models and presented the results in Table 3.

Table 3.

Comparison of measurement models.

As shown in Table 2, the baseline five-factor model fits the data well [χ2 = 1284.75; df = 334; χ2/df = 3.85; RMSEA = 0.068; CFI = 0.93; RMR = 0.053; Standardized RMR = 0.057; TLI = 0.91; GFI = 0.89]. The comparison of the baseline model with four alternative models reveals that the comparative fit index (CFI) for the five-factor model was 0.93; the root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA) was 0.068 (which is less than the cutoff value of 0.08), and these goodness-of-fit statistics indicate good fit of the model to the data (Browne & Cudeck, 1993). To sum, these statistics provide evidence of distinctiveness of all five constructs.

4.2. Descriptive Statistics, Discriminant Validity, and Reliability

The descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations, and zero-order correlations) were mentioned in Table 4.

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics—means, standard deviations, zero-order correlations, and reliability.

As can be seen in Table 4, the reliability coefficient Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability (CR) values for all five variables was over 0.70; average variance extracted (AVE) estimates were well over the threshold level of 0.5, thus establishing reliability (Hair et al., 2019). Further, the square root of AVE of all these five variables were greater than the correlations between the variables. For example, correlation between dialogue and inquiry and empowerment was 0.42, which is less than the square root of AVEs 0.73 and 0.76, respectively. We also assessed discriminant validity by using Heterotrait–Monotrait (HTMT) criterion and Fornell and Larcker (1981) criterion, and results confirm that the values were within the acceptable range, thus establishing discriminant validity (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Table 5 and Table 6 show discriminant validity [HTMT criterion] and Fornell and Larcker (1981) criterion.

Table 5.

Discriminant validity [HTMT criterion].

Table 6.

Discriminant validity [Fornell–Larcker criterion].

4.3. Multicollinearity

To assess the multicollinearity, we checked the variance inflation factor (VIF) and found that these values were less than 5, thus vouching for absence of multicollinearity. The collinearity results are mentioned in Table 7.

Table 7.

Collinearity diagnosis [variance inflation factor (VIF) values].

4.4. Common Method Bias (CMB)

Since cross-sectional studies have inherent problem of CMB, it is necessary to check whether the data is infected by CMB. We have performed three statistical checks for this. First, we used traditional Harman’s single-factor analysis and found that single factor accounted for 24.36% of variance (which is less than 50%), indicating CMB is not a problem with the data. The contemporary researchers contend that Harman’s single-factor analysis has some inherent problems, and hence not reliable (Howard et al., 2024), and suggested some other robust techniques to assess CMB. Second, we compared goodness of statistics of one-factor with five-factor model and found that one-factor model has yielded poor goodness of fit [see Table 3]. Third, as additional widely used method, we performed latent factor method through which we loaded all the indicators into a single factor and rotated each time and found that the inner VIF values were less than 3.3, suggesting that CMB is not a problem in this research (Kock, 2015).

4.5. Hypotheses Testing

First, we checked if any of the demographic variables [age, income, education, and experience] have any influence on the variables by running regressions and found that none of the demographic variables have significant effect on all five variables. Therefore, we did not include demographic variables in the analysis.

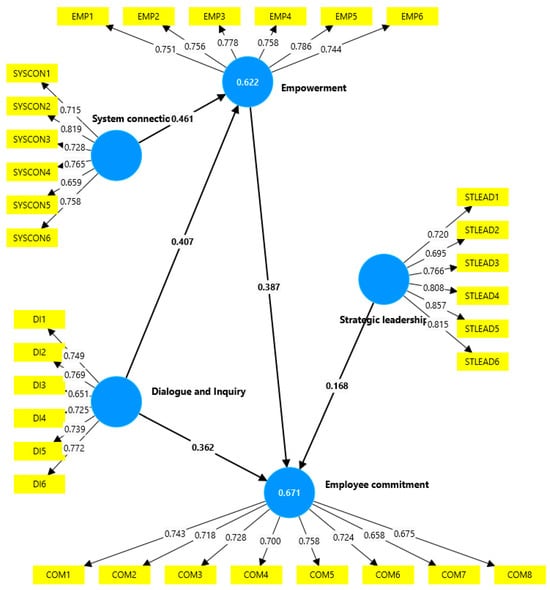

We performed path analysis using Smart PLS software and presented the results in Table 8.

Table 8.

Path coefficients.

The results reveal that the effect of dialogue and inquiry on (i) employee commitment was positive and significant (H1: β = 0.362; p < 0.001) and (ii) empowerment was positive and significant (H2: β = 0.407; p < 0.001). The path coefficient of empowerment on employee commitment was positive and significant (H3: β = 0.387; p < 0.001). These results render support for H1, H2, and H3.

Path analysis is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Structural model (path analysis).

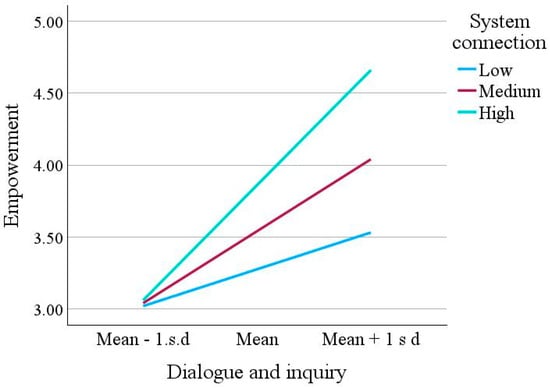

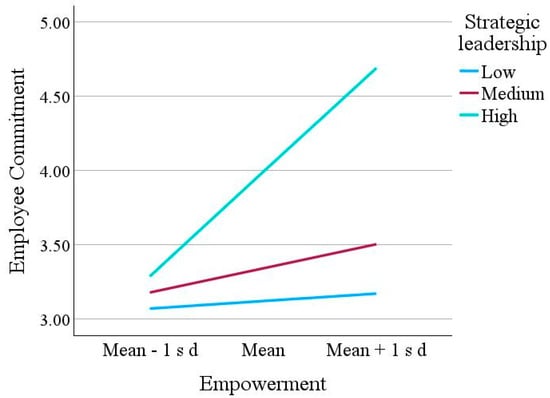

Since structural equation modeling breaks down to show moderating effects (Pedhazur & Schmelkin, 1991), we used Hayes (2018) PROCESS macros (Model 1). The results reveal that the regression coefficient of interaction term—dialogue and inquiry and system connection—was significant and positive (H5: βdialogue and inquiry × system connection = 0.132; p < 0.05). The regression coefficient of interaction term—empowerment and strategic leadership—was positive and significant (H6: βempowerment × strategic leadership = 0.174; p < 0.05). These results render support for H5 and H6.

Figure 3.

System connection moderates between dialogue and inquiry and empowerment.

As demonstrated in Figure 3, at higher levels of system connection, the effect of dialogue and inquiry on empowerment is higher, whereas at lower levels of system connection, the effect is lower (though positive). Change in the slopes of curves is clearly noticeable, which supports the moderation hypothesis (H5).

Figure 3 illustrates the interaction of empowerment and strategic leadership on employee commitment. As can be seen in the Figure 4, higher levels of strategic leadership are associated with higher impact of empowerment on employee commitment. The differences in slopes bear testimony to the moderation hypothesis (H6).

Figure 4.

Strategic leadership moderates between empowerment and employee commitment.

4.6. Mediation Hypothesis

To check the mediation hypothesis, we tested whether the indirect effect of dialogue and inquiry on employee commitment through empowerment (Hayes, 2018). We found that the indirect effect is positive and significant, as can be seen from Table 9.

Table 9.

Mediation hypothesis.

The PROCESS macros results show that the indirect effect (0.1575) is significant as there is no 0 in the lower and upper limits [BCCI Lower limit = 0.1259; BCCI Upper limit = 0.2841]. The indirect effect is calculated as the product of effect of dialogue and inquiry on empowerment (0.4070) and empowerment on employee commitment (0.3870) [i.e., 0.4070 × 0.3620 = 0.3870].

5. Discussion

This study aims to explore the nexus between learning through dialogue and inquiry and employee commitment. Most importantly, the roles of empowerment, system connection, and strategic leadership are emphasized. A conceptual model was developed and tested by collecting data from 346 respondents from a multi-specialty hospital in southern India, and the results validated the model.

First, the findings suggest that dialogue and inquiry have a significant and positive impact on employee commitment (Hypothesis 1), which is consistent with the findings from the literature (Battistelli et al., 2019; Kamali et al., 2017; Malik & Garg, 2017; J. P. Meyer et al., 2002; Naim & Lenka, 2020; Ryu & Moon, 2019). It is logical that when healthcare professionals engage in dialogue and inquiry, they are more likely to show their commitment (affective, continuance, and normative commitment). A plethora of research has heavily documented the impact of learning in organizations on employee commitment (Somaskandan et al., 2022). Second, the results indicate that dialogue and inquiry are precursors to empowerment (Hypothesis 2), corroborating the studies conducted in the past in other industries (Lawler, 1994; Metcalf et al., 2018; Paradis et al., 2014; Pearson et al., 2021). When employees engage in dialogue, they feel that the level of empowerment is high because such engagement in dialogue results in making strategic decisions. Though the top management team is involved in making strategic decisions, they engage in dialogue and inquiry with the healthcare professionals, which gives them a feeling of empowerment. Third, our research found that empowerment is a precursor to employee commitment (Hypothesis 3). Several scholars in the past have documented positive associations of empowerment with affective, normative, and continuance commitment (Chen et al., 2007; Dainty et al., 2002; J. P. Meyer et al., 1993; Mowday et al., 1979; Mills & Ungson, 2003; Nayak et al., 2018; Somaskandan et al., 2022).

The fourth key finding in this study supports the indirect effect of dialogue and inquiry on employee commitment through empowerment (Hypothesis 4). Though the literature is scant in vouching for this finding, anecdotal evidence and direct effects of dialogue and inquiry on empowerment and commitment provide ample testimony (Aggarwal et al., 2018; Brunetto et al., 2011).

Fifth, this study investigated the moderating role of system connection in the relationship between dialogue inquiry and empowerment (Hypothesis 5), and the results support this moderation effect. In the absence of prior studies to vouch for this relationship, we rely on anecdotal evidence and logic in understanding that organizational-level learning through system connection strengthens the positive effect of dialogue and inquiry (individual-level learning) on empowerment (organizational level) (Carayon et al., 2011; Stoller, 2014; Zhao et al., 2007). Sixth, the moderating effect of strategic leadership in the relationship between empowerment and employee commitment (Hypothesis 6) found support in this study. When the top management team exhibits strategic leadership in a committed way, it is more likely that the employees increase their level of commitment, especially when they feel empowered. Though direct effects of strategic leadership on various organizational outcomes have been documented in the literature (Awais-E-Yazdan et al., 2023; Gözükara et al., 2018; Jamali et al., 2009; Mendes & França, 2024; Giallouros et al., 2023), none of the previous studies delved into strategic leadership as a moderating variable. So, we consider this an exploratory study. To sum up, the hypothesized relationships were found to support this research.

We did not study the effect of employee commitment on service quality perceived by patients in healthcare organizations. We consider that as a future research agenda.

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

This study has several contributions to advancing OLT and OCT, particularly in relation to healthcare sector. First, the study highlights the importance of various individual and organizational learning components in enhancing employee commitment. More specifically, the study underscores the importance of inter-relationships between individual learning (dialogue and inquiry) and organizational learning (empowerment, system connection, and strategic leadership). Organizational participants’ dialogue and inquiry in assimilating and sharing information influence empowerment positively. Second, this research adds to the existing literature by emphasizing empowerment’s role in increasing employee commitment. Third, this research adds to the literature by providing empirical evidence that dialogue and inquiry have an indirect on employee commitment through empowerment. While direct benefits have been documented by previous scholars (Aggarwal et al., 2018; Brunetto et al., 2011), empowerment as a mediator needs to be recognized.

The fourth pivotal contribution of this research is the interaction of system connection with dialogue and inquiry in influencing empowerment. When organizational participants engage in dialogues and discussions, the system connection in terms of employees’ focus on stakeholders (e.g., customers and community) escalates empowerment. Fifth, strategic leadership plays a vital role in strengthening the positive effect of empowerment on employee commitment. When leaders provide learning and training opportunities and share the latest information with employees about customers, competitors, industry trends, and organizational directions, employees exhibit higher levels of commitment. As strategic leadership is seen as providing direction to the employees and instilling confidence in reaching the vision, employees are more likely to remain committed to the organization. Thus, the present study makes five significant contributions to theory of learning and commitment in the context of healthcare organizations.

5.2. Practical Implications

This study has several implications for healthcare organizations’ practicing managers and administrators. First, to serve the customers (patients) better, employees must engage in continuous learning through dialogue and inquiry. Further, administrators need to promote organizational learning by providing opportunities for empowerment. When members give their opinions and honest feedback to each other, treat each other with respect, and build trust, administrators will be motivated to give additional responsibilities to the employees, resulting in empowerment. Second, when employees are given control over the resources to accomplish the tasks, they perform well and exhibit high level of commitment to the organization.

Further, empowerment in recognizing the people for taking the initiative and inviting them to contribute to the organization’s vision makes employees feel responsible and show higher levels of commitment. Third, administrators of healthcare organizations need to recognize the importance of educating the employees to look after the interests of stakeholders and provide them with what they want so that they remain competitive in the industry. When healthcare professionals work with the outside community to meet mutual demands, individual learning through dialogue and inquiry is vital in enhancing empowerment. When system connection is viewed as tying the organization to the demands stemming from the external environment, employees must emphasize new learning methods through dialogue and inquiry. Administrators need to ensure that all stakeholders work aligning with the goals of healthcare organizations, i.e., to take care of patients and enhance patient satisfaction.

The fourth significant practical implication of this study is the role of strategic leadership in strengthening the relationship between empowerment and employee commitment. When leaders mentor and coach the employees and create opportunities to learn, they will be happy to spend the rest of their careers with the organization, showing a high level of affective commitment. They also, in addition, discuss the positives of the organization, thus resulting in increased goodwill. This study, in sum, provides valuable insights to administrators and practicing managers about strategic leadership and system connections that strengthen the relationship between dialogue and inquiry, empowerment, and employee commitment. This study made a significant contribution to the bourgeoning literature and theories of learning and employee commitment.

5.3. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

This research has limitations. First, this study focused on respondents from the healthcare industry from a developing country, India. Therefore, the result should be interpreted considering the conditions prevailing in the country, which ranks number one in population. Second, a relatively small sample size is another limitation, though we have taken care to collect data representative of the population. Third, this study was limited to five variables. Fourth, as with any cross-sectional study, this research may have CMB and social desirability bias. However, we have conducted various statistical tests to remedy CMB and mentioned the anonymity of the responses to the respondents to minimize social desirability bias.

This research has several avenues for future studies. The researchers may include more extensive samples across different sectors to test the hypothesized relationships. Future studies may also consider how dialogue and inquiry are related to employee commitment in developed countries, which differ from developing countries. We also suggest that the researchers include additional variables that may mediate or moderate the relationship between empowerment and employee commitment. For example, psychological capital, emotional intelligence, stress, and burnout influence the relationship between empowerment and employee commitment. Further, future researchers may investigate the relationship between employee commitment and service quality provided in healthcare organizations to patients. Additionally, future studies may include several multi-specialty hospitals in India and have a bigger sample to increase generalizability of findings.

5.4. Conclusions

This research explores the nexus between individual learning through dialogue, inquiry, empowerment, and employee commitment. The results from this study provide valuable insights into the moderating effects of system connection and strategic leadership in influencing the relationship between dialogue and inquiry, empowerment, and employee commitment. Deciphering dynamic interactions among multidimensional constructs of learning (dialogue and inquiry, system connection, empowerment, and strategic leadership) to influence employee commitment provides a direction to the administrators and policymakers in healthcare organizations to understand the antecedents of providing service to patients. This study provides a valuable platform for further investigation and research on empowerment and commitment to healthcare organizations. This study provides important insights that may help administrators and decision-makers create a climate encouraging empowerment that facilitates employee commitment in healthcare organizations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.E., N.T., S.S., K.S. and M.C.; methodology, N.E., S.S., S.P. and M.C.; software, K.S., S.P. and M.C.; validation, N.T., S.S., K.S., S.P. and M.C.; formal analysis, S.P. and M.C.; investigation, N.T., S.S. and K.S.; resources, N.E., N.T., S.S. and M.C.; data curation, N.E., N.T., S.P. and M.C.; writing—original draft preparation, N.E., N.T., S.S., S.P. and M.C.; writing—review and editing, N.E., N.T., S.S., K.S., S.P. and M.C.; visualization, N E., N.T., S.S. and S.P.; supervision, N.T. and S.S.; project administration, N.T. and S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The research involved a non-clinical, non-interventional survey conducted among adult professionals in the Indian healthcare industry, focusing exclusively on their organizational perceptions and experiences (e.g., empowerment, dialogue, and commitment). The study did not collect any sensitive personal data, biological material, or involve any form of medical intervention. In line with applicable Indian national guidelines for social science research, and consistent with common international academic practice for anonymous, voluntary, and non-sensitive surveys in organizational settings, this type of research is exempt from formal ethics approval. Participants were fully informed about the purpose of the study, participation was voluntary, and informed consent was obtained prior to data collection.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from the respondents.

Data Availability Statement

The data will be made available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors do not have any competing interests.

Abbreviations

| AVE | Average variance extracted estimate |

| CR | Composite reliability |

| CFA | Confirmatory factor analysis |

| CMV | Common method variance |

| LLCI | Lower level confidence intervals |

| ULCI | Upper level confidence intervals |

References

- Aggarwal, A., Dhaliwal, R. S., & Nobi, K. (2018). Impact of structural empowerment on organizational commitment: The mediating role of women’s psychological empowerment. Vision, 22(3), 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghaei, N., Ziace, A., & Shahrbanian, S. (2012). Relationship between learning organization and organizational commitment among employees of Sport and Youth Head Office of western provinces of Iran. European Journal of Sports and Exercise Science, 1(3), 59–69. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, A. O., Abdalla, A. M., & Ali, A. M. (2025). Investigating the impact of soft TQM practices on employees’ organizational commitment in governmental Sudanese petroleum organizations. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S., Abd Manaf, N. H., & Islam, R. (2018). Effect of Lean Six Sigma on quality performance in Malaysian hospitals. International Journal of Health Care Quality Assurance, 31(8), 973–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, N. J., & Meyer, J. P. (1990). The measurement and antecedents of affective continuance and normative commitment to the organization. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 63(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annan-Prah, E. C., Baffoe, F., & Andoh, R. P. K. (2023). People aspect of learning organisation and performance of administrative staff in a public university context. The Learning Organization, 30(5), 590–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyris, C., & Schon, D. (1978). Organizational learning: A theory of action perspective. Addison Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, J. S., & Overton, T. S. (1977). Estimating non-response bias in mail surveys. Journal of Marketing Research, 14(3), 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awais-E-Yazdan, M., Hassan, Z., Spulbar, C., Birau, R., Mushtaq, M., & Bărbăcioru, I. C. (2023). Relationship among leadership styles, employee’s well-being and employee’s safety behavior: An empirical evidence of COVID-19 from the frontline healthcare workers. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 36(1), 2173629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battistelli, A., Odoardi, C., Vandenberghe, C., Napoli, G. D., & Piccione, L. (2019). Information sharing and innovative work behavior: The role of work-based learning, challenging tasks, and organizational commitment. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 30(3), 361–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, P., Sharma, H., & Savita, U. (2025). Linkage between empowerment, commitment and organizational citizenship behavior in Indian retail sector. The Learning Organization: An International Journal, 32(3), 459–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatnagar, J. (2007). Predictors of organisational commitment in India: Strategic HR roles, organisational learning capability and psychological empowerment. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 18(10), 1782–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhojak, N. P., Modi, A., Patel, J. D., & Patel, M. (2022). Measuring patient satisfaction in emergency department: An empirical test using structural equation modeling. International Journal of Healthcare Management, 16(3), 412–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, K. K., Gardner., J. W., & Schweikhart, S. (2012). Process quality improvement: An examination of general vs. outcome-specific climate and practices in hospitals. Journal of Operations Management, 30(4), 325–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In K. A. Bollen, & J. S. Long (Eds.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 136–162). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Brunetto, Y., Shacklock, K., Bartram, T., Leggat, S. G., Farr-Wharton, R., Stanton, P., & Casimir, G. (2011). Comparing the impact of leader–member exchange, psychological empowerment and affective commitment upon Australian public and private sector nurses: Implications for retention. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 23(11), 2238–2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capone, V., Donizzetti, A. R., & Park, M. S.-A. (2023). Validation and psychometric evaluation of the COVID-19 risk perception scale (CoRP): A new brief scale to measure individuals’ risk perception. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 21, 1320–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carayon, P., Bass, E., Bellandi, T., Gurses, A., Hallbeck, S., & Mollo, V. (2011). Socio-technical systems analysis in health care: A research agenda. IIE Transactions on Healthcare Systems Engineering, 1(1), 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G., Kirkman, B. L., Kanfer, R., Allen, D., & Rosen, B. (2007). A multilevel study of leadership, empowerment, and performance in teams. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(2), 331–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahleez, K. A., Al-Brwani, R., Salah, M., & AL-Sinawi, S. (2025). Sustaining workplace through emotional intelligence: The role of empowering leadership in fostering engagement and risk-taking in healthcare. Journal of Health Organization and Management. online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dainty, A. R., Bryman, A., & Price, A. D. (2002). Empowerment within the UK construction sector. Leadership and Organisation Development Journal, 23(6), 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawood-Khan, H. K., Naina, S. K., & Parayitam, S. (2024). The antecedents of patient satisfaction: Evidence from super-specialty hospitals in Tiruchirappalli in India. International Journal of Healthcare Management, 17(2), 305–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeCicco, J., Laschinger, H., & Kerr, M. (2006). Perceptions of empowerment and respect: Effect on nurses organisational commitment in nursing homes. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 32(5), 49–56. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Eapen, N., Thundiyil, N., & Shenai, S. (2022a). Impact of work retention and engagement on service quality among nurses in little flower hospital, Angamali, Kerala. Anvesak, 52(11), 18–40. [Google Scholar]

- Eapen, N., Thundiyil, N., & Shenai, S. (2022b). Service quality assessment of laboratory technicians in multispeciality private clinics in Pathanamthitta district, Kerala. Purana, 65(11), 71–84. [Google Scholar]

- Effken, J. A. (2002). Different lenses, improved outcomes: A new approach to the analysis and design of healthcare information systems. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 65(1), 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gayoso-Rey, M., Martınez-Lopez de Castro, N., Paradela-Carreiro, A., Samartın-Ucha, M., RodrıguezLorenzo, D., & Pineiro-Corrales, G. (2020). Metodologıa lean: Diseno y evaluaci on de un modelo estandarizado de almacenaje de medicacion. Farmacia Hospitalaria: Organo Oficial De Expresion Cientifica De La Sociedad Espanola De Farmacia Hospitalaria, 45(1), 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giallouros, G., Nicolaides, C., Gabriel, E., Economou, M., Georgiou, A., Diakourakis, M., Soteriou, A., & Nikolopoulos, G. K. (2023). Enhancing employee engagement through integrating leadership and employee job resources: Evidence from a public healthcare setting. International Public Management Journal, 27(4), 533–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, S., & Gregory, R. (1997). Benchmarking the learning capability of organizations. European Management Journal, 15(5), 575–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalan, H. S., & Misra, A. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic and challenges for socio-economic issues, healthcare and National Health Programs in India, Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome. Clinical Research & Reviews, 14, 757–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gözükara, İ., Çolakoğlu, N., & Şimşek, Ö. F. (2018). Development culture and TQM in Turkish healthcare: Importance of employee empowerment and top management leadership. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 30(11–12), 1302–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffeth, R. W., Hom, P. W., & Gaertner, S. (2000). A meta-analysis of antecedents and correlates of employee turnover: Update moderator tests and research implications for the next millennium. Journal of Management, 26(3), 463–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, M. R. (2010). The double-edged swords of autonomy and external knowledge: Analyzing team effectiveness in a multinational organization. Academy of Management Journal, 53(5), 989–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2019). Multivariate data analysis (8th ed.). Cengage Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Hanafy, H. A., Al-Hajla, A. H., & Elsharnouby, M. H. (2025). Empowering leadership and employee innovation: Unraveling the roles of psychological empowerment and knowledge sharing. Journal of Humanities and Applied Social Sciences. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hendri, M. I. (2019). The mediation effect of job satisfaction and organizational commitment on the organizational learning effect of the employee performance. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 68(7), 1208–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, M. C., Boudreaux, M., & Oglesby, M. (2024). Can Harman’s single-factor test reliably distinguish between research designs? Not in published management studies. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 33(6), 790–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X., Shi, K., Zhang, Z., & Cheung, Y. L. (2006). The impact of participative leadership behavior on psychological empowerment and organisational commitment in Chinese state-owned enterprises: The moderating role of organisational tenure. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 23(3), 345–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, D., Sidani, Y., & Zouein, C. (2009). The learning organization: Tracking progress in a developing country: A comparative analysis using the DLOQ. The Learning Organization, 16(2), 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janicijevic, I., Seke, K., Djokovic, A., & Filipovic, T. (2013). Healthcare workers satisfaction and patient satisfaction—Where is the linkage? Hippokratia, 17(2), 157–162. [Google Scholar]

- Janssen, O. (2004). The barrier effect of conflict with superiors in the relationship between employee empowerment and organisational commitment. Work and Stress, 18(1), 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallal, A., Griffen, D., & Jaeger, C. (2020). Using lean six sigma methodologies to reduce risk of warfarin medication omission at hospital discharge. BMJ Open Quality, 9(2), e000715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamali, M., Asadollahi, S. H., Afshari, M., Mobaraki, H., & Sherbaf, N. (2017). Studying the relationship between organizational learning and organizational commitment of staffs of well-being organization in Yazd province. Evidence Based Health Policy. Management & Economics, 1(4), 178–85. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, H. J., Molloy, J. C., & Brinsfield, C. T. (2012). Reconceptualizing workplace commitment to redress a stretched construct: Revisiting assumptions and removing confounds. Academy of Management Review, 37(1), 130–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. (2015). Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. International Journal of e-Collaboration, 11(4), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krejcie, R. V., & Morgan, D. W. (1970). Determining sample size for research activities. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 30(3), 607–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawler, E. E. (1994). Total quality management and employee involvement: Are they compatible? Academy of Management Executive, 8(1), 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. Y., McFadden, K. L., Lee, M. K., & Gowen, C. R. (2021). U.S. hospital culture profiles for better performance in patient safety, patient satisfaction, six sigma, and lean implementation. International Journal of Production Economics, 234, 108047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, Z., Angele-Halgand, N., Churruca, K., Ellis, L. A., & Braithwaite, J. (2021). The impact of lean management on frontline healthcare professionals: A scoping review of the literature. BMC Health Services Research, 21(1), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, P., & Garg, P. (2017). The relationship between learning culture, inquiry and dialogue, knowledge sharing structure and affective commitment to change. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 30(4), 610–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansoor, T., Umer, M., & Duenas, A. (2025). Unlocking team performance: The interplay of team empowerment, shared leadership, and relationship conflict in healthcare sector. Strategy & Leadership, 53(2), 188–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsick, V. J., & Watkins, K. E. (2003). Demonstrating the Value of an Organization’s Learning Culture: The Dimensions of the Learning Organization Questionnaire. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 5(2), 132–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, J. E., Gilson, L. L., & Ruddy, T. M. (2006). Empowerment and team effectiveness: An empirical test of an integrated model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(1), 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendes, L., & França, G. (2024). Lean thinking and risk management in healthcare organizations: A systematic literature review and research agenda. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercurio, Z. A. (2015). Affective commitment as a core essence of organizational commitment: An integrative literature review. Human Resource Development Review, 14(4), 389–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalf, A. Y., Habermann, M., Fry, T. D., & Stoller, J. K. (2018). The impact of quality practices and employee empowerment in the performance of hospital units. International Journal of Production Research, 56(18), 5997–6014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J., & Allen, N. (1997). Commitment in the workplace: Theory, research, and application. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, J. P., Allen, N. J., & Smith, C. A. (1993). Commitment to organizations and occupations: Extension and test of three component conceptualization. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(4), 538–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J. P., Stanley, D. J., Herscovitch, L., & Topolnytsky, L. (2002). Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: A meta-analysis of antecedents, correlates, and consequences. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 61(1), 20–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, P. K., & Ungson, G. R. (2003). Reassessing the limits of structural empowerment: Organisational constitution and trust as controls. Academy of Management Review, 28(1), 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowday, R. T., Steers, R. M., & Porter, L. W. (1979). The measurement of organizational commitment. Journal of Vocational Behaviour, 14(2), 224–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naim, M. F., & Lenka, U. (2020). Organizational learning and Gen Y employees’ affective commitment: The mediating role of competency development and moderating role of strategic leadership. Journal of Management & Organization, 26, 815–7831. [Google Scholar]

- Nayak, T., Sahoo, C. K., & Mohanty, P. K. (2018). Workplace empowerment, quality of work life and employee commitment: A study on Indian healthcare sector. Journal of Asia Business Studies, 12(2), 117–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, C. A., & Chatman, J. (1986). Organizational commitment and psychological attachment: The effects of compliance, identification and internalization on pro-social behaviour. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71(3), 492–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradis, E., Leslie, M., Puntillo, K., Gropper, M., Aboumatar, H. J., Kitto, S., & Reeves, S. (2014). Delivering interprofessional care in intensive care: A scoping review of ethnographic studies. American Journal of Critical Care, 23(3), 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, M., Sunderland, L., & Hendy, C. (2021). Open dialogue and co-production: Promoting a dialogical practice culture in the co-production of teaching and learning within nurse education. The Journal of Mental Health Training, Education and Practice, 16(5), 364–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedhazur, E. J., & Schmelkin, L. P. (1991). Measurement, design, and analysis: An integrated approach (Student ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Perreira, T. A., Morin, A. J. S., Hebert, M., Gillet, N., Houle, S. A., & Berta, W. (2018). The short form of the Workplace Affective Commitment Multidimensional Questionnaire (WACMQ-S): A bifactor-ESEM approach among healthcare professionals. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 106(1), 62–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rod, M., & Ashill, N. J. (2010). Management commitment to service quality and service recovery performance: A study of frontline employees in public and private hospitals. International Journal of Pharmaceutical and Healthcare Marketing, 4(1), 84–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, R. C., Kumar, N., & Pak, O. G. (2009). The effect of organizational learning on organizational commitment, job satisfaction and work performance. The Journal of Applied Business Research, 25(6), 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, G., & Moon, S.-G. (2019). The effect of actual workplace learning on job satisfaction and organizational commitment: The moderating role of intrinsic learning motive. Journal of Workplace Learning, 31(8), 481–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadat, V., & Saadat, Z. (2016). Organizational learning as a key role of organizational success. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences, 230, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senge, P. M. (1990). The fifth discipline: The art and practice of the learning organization. Doubleday. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, C., & Shin, D. (2025). Leveraging structural empowerment and human capital for organizational innovation. International Journal of Manpower. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoaib, M., Nawal, A., Korsakiene, R., Zámečník, R., Asad Ur Rehman, A. U., & Raišien, A. G. (2022). Performance of Academic Staff during COVID-19 Pandemic-Induced Work Transformations: An IPO Model for Stress Management. Economies, 10, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shreffler, J., Petrey, J., & Huecker, M. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on healthcare worker wellness: A scoping review. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine, 21(5), 1059–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, S. F., & Narver, J. C. (1995). Market orientation and the learning organization. Journal of Marketing, 59(3), 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solinger, O., Van Olffen, W., & Roe, R. A. (2008). Beyond the three-component model of organizational commitment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(1), 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somaskandan, K., Arulandu, S., & Parayitam, S. (2022). A moderated-mediation model of individual learning and commitment: Evidence from healthcare industry in India (part II). The Learning Organization, 29(4), 392–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, G. M. (1995). Psychological empowerment in the workplace: Dimensions, measurement and validation. Academy of Management Journal, 38(5), 1442–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoller, J. K. (2014). Help wanted: Developing clinician leaders. Perspectives on Medical Education, 3(3), 233–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tlapa, D., Tortorella, G., Fogliatto, F., Kumar, M., Mac Cawley, A., Vassolo, R., Enberg, L., & BaezLopez, Y. (2022). Effects of lean interventions supported by digital technologies on healthcare services: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(15), 9018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, R. S., Hattingh, T. S., & Meijer, H. (2022). Factors affecting the sustainability of lean in healthcare: A systematic literature review. South African Journal of Industrial Engineering, 33(3), 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J., Liu, Y., Chen, Y., & Pan, X. (2014). The effect of structural empowerment and organizational commitment on Chinese nurses job satisfaction. Applied Nursing Research, 27(3), 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X., Flynn., B. B., & Roth, A. V. (2007). Decision sciences research in China: Current status, opportunities, and propositions for research in supply chain management, logistics, and quality management. Decision Sciences, 38(1), 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).