Abstract

This study investigates how transformational leadership impacts pro-environmental and proactive work behaviors through key employee psychological states: self-efficacy, change orientation, and positive affect. We argue that transformational leadership significantly enhances these psychological states, which can drive proactive and pro-environmental workplace behaviors. We used survey data collected via Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk) from 542 full-time employees in the United States. Data analysis used Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). The results confirm that transformational leadership significantly enhances self-efficacy, change orientation, and positive affect, factors that in turn promote pro-environmental work behavior. Moreover, change orientation and positive affect (but not self-efficacy) favor proactive work behavior. These findings emphasize the role of employee psychological mechanisms in translating leadership into sustainable workplace behavior. The study contributes to the leadership and sustainability literature by clarifying how internal psychological resources act as behavioral catalysts. Leaders can formulate strategies focusing on emotional and cognitive empowerment. Limitations and future research directions are also discussed.

1. Introduction

As environmental degradation accelerates and stakeholders increasingly demand responsible corporate practices, organizations are under intensifying scrutiny to promote sustainable behaviors at all operational levels (Robertson & Barling, 2013). While institutional responses to environmental concerns have traditionally focused on technological innovation and regulatory compliance, scholars have increasingly recognized the significance of employee-level proactive work behavior (PWB), including pro-environmental behavior (PEB), as a vital driver of organizational sustainability outcomes (Graves et al., 2013; Mughal et al., 2022). Proactive and prosocial employee behaviors aimed at promoting environmentally sustainable practices within organizations are referred to as PEB (Boiral et al., 2015; Han et al., 2009). One the other hand, PWB includes behaviors concerning “taking control of, and aiming to bring about change within, the internal organization” (Parker & Collins, 2010).

Organizational leaders can impact a range of organizational outcomes (such as employee motivation, organizational and financial performance), including PEB and PWB. Despite prior studies exploring leadership—particularly transformational leadership (TL)—a key lever through which organizations can influence individual employee behavior toward objectives, including environmental objectives (Y.-S. Chen et al., 2014; Mansoor & Wijaksana, 2023; Tims et al., 2011), existing research often treats PEB and PWB separately, leaving an empirical and theoretical gap in understanding how leaders can simultaneously activate both types of employee behaviors. Our study aims to fill such gap.

Our study focuses on the psychological states of employees—defined here as the leadership-induced enhancement of employees’ internal psychological resources such as self-efficacy, change orientation, and positive affect—as a central mechanism linking TL to sustainable workplace behavior. While prior research supports the influence of TL on self-efficacy (Walumbwa et al., 2004), change orientation (Baik et al., 2018), and positive affect (Chaubey et al., 2019), few studies have jointly tested these variables as mediators, particularly in models that consider both environmental and general workplace behaviors.

Transformational leadership, defined by its components of inspirational motivation, individualized consideration, intellectual stimulation, and idealized influence (Bass & Avolio, 1994), has been consistently associated with positive organizational outcomes such as employee engagement, innovation, and adaptability (Bakker et al., 2023; Tims et al., 2011). More recently, TL has been theorized and empirically validated as a facilitator of sustainable workplace behaviors, particularly when leaders explicitly promote environmental values and practices (Y.-S. Chen et al., 2014; Althnayan et al., 2022). Despite growing interest in transformational leadership, limited research has unpacked the underlying psychological mechanisms by which TL motivates PWB and PEB. As a result, a critical gap exists in understanding how transformational leaders influence the cognitive and emotional states that serve as antecedents to such behaviors (Cai et al., 2020; Miller et al., 2022). In addition, some studies find self-efficacy to be a robust predictor of proactive behavior (Bindl & Parker, 2011), while others report weaker or non-significant effects (Den Hartog & Belschak, 2012), suggesting that additional psychological variables or contextual moderators may play a role.

Our study takes a novel approach by integrating leadership theory with psychological constructs that mediate behavior. Among these, self-efficacy—a person’s belief in their ability to execute specific actions (Bandura, 1977)—stands out as a foundational determinant of behavioral intention and follow-through. While research has linked TL to enhanced self-efficacy in general work contexts (Walumbwa et al., 2004; Salanova et al., 2020), few studies have examined how transformational leaders can cultivate environmental self-efficacy in employees, nor how this, in turn, leads to greater engagement in pro-environmental and proactive behaviors (Robertson & Barling, 2013; Faraz et al., 2021).

In addition to self-efficacy, change orientation, and positive affect are crucial yet underexplored psychological constructs that may mediate the relationship between TL and work behavior. Change orientation refers to an individual’s readiness and willingness to embrace new ideas and approaches, particularly relevant in promoting organizational transformations (Baik et al., 2018; Yuspahruddin et al., 2024). Positive affect—characterized by enthusiasm, energy, and optimism—has also been linked to proactive work behavior and may serve as a motivational catalyst in various proactive work behaviors (Bindl et al., 2012; Caniëls & Baaten, 2018). However, the interaction of these psychological factors with leadership behaviors in the context of proactive and pro-environmental work behavior remains inadequately addressed in the current literature (Arnold et al., 2015; Grošelj et al., 2020).

Beyond the individual psychological level, perceived organizational support (POS) is vital in promoting employee behaviors that support environmental and organizational goals. Based on social exchange theory, POS refers to employees’ perceptions of how much the organization values their contributions and well-being (Kurtessis et al., 2015). POS is fundamentally linked to social exchange theory, which posits that employees assess the rewards and support received from their organization and how it impacts their commitment and performance (Kurtessis et al., 2015; Eisenberger et al., 2001). In contrast, leadership influence predominantly reflects the direct impact of a leader’s behavior on subordinates (L. Chen et al., 2024; Suifan et al., 2018). While leaders can influence POS, it does not replace the leader’s direct influence on employees’ behavioral outcomes. Specifically, Saleh et al. highlight that POS acts as a mediator, enhancing the impact of visionary leadership on creativity rather than substituting it (Saleh et al., 2024). It is well established that transformational leaders enhance POS through empathetic and supportive behavior (L. Chen et al., 2024; Dinç et al., 2022) and that higher POS, in turn, increases employee commitment and initiative-taking, including sustainable workplace practices (Tantawi & Noviana, 2024; Saifulina et al., 2021). However, few models have considered how TL and POS jointly contribute to environmental and proactive outcomes or how they might interact with self-efficacy and affective mechanisms.

To address these gaps, the present study develops and tests an integrated conceptual framework that links transformational leadership to pro-environmental and proactive employee behaviors through the mediating effects of self-efficacy, change orientation, positive affect, and perceived organizational support. The model posits that transformational leaders, instilling confidence, fostering adaptability, and encouraging positive emotional states, create the internal psychological conditions necessary for employees to engage in sustainable and self-initiated actions. It further argues that TL shapes employees’ perceptions of organizational support, amplifying psychological empowerment’s effects on behavior.

This research contributes significantly to the academic discourse in several key areas. First, it simultaneously examines PEB and PWB within a single theoretical framework, bridging the literature on proactive behavior with sustainability studies. By demonstrating how the same psychological resources underpin environmentally and organizationally proactive acts, our study enriches the understanding of these crucial areas. Second, it extends transformational leadership theory by articulating the psychological processes—namely, self-efficacy and emotional state—through which TL simultaneously impacts employee behavior in the environmental and general proactive work domains. Third, it enriches the pro-environmental behavior literature by integrating cognitive, affective, and organizational mechanisms into a unified explanatory model.

As organizations increasingly embed sustainability into their strategic goals, it is important to understand how leaders can mobilize individual contributions that offer a roadmap for managers to cultivate the psychological capacities—confidence, adaptability, and emotional engagement—required for employees to act as sustainability champions. Additionally, the research highlights the need for systemic structures that reinforce leadership efforts and sustain employee motivation and commitment. This study responds to a pressing need for holistic models that capture the interplay between leadership behavior, psychological mechanisms, and employee-level sustainability outcomes. Integrating diverse theoretical perspectives and empirical insights contributes to a deeper understanding of how leadership can serve as a fulcrum for individual and collective action in support of environmental and organizational change.

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Development

According to the Self-determination theory, individuals are more likely to experience passion when their intrinsic needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness are fulfilled (Deci & Ryan, 2000). Leaders who display these behaviors encourage followers to exceed their self-interest to achieve broader collective goals, foster innovative thinking, and facilitate personal growth (Asbari, 2020; Bakker et al., 2023; Saad Alessa, 2021). Social Exchange Theory (SET) stresses the two-way interactions between leaders and followers. Followers engage in PEB and PWB when leaders model and reward it (Afsar et al., 2018; Javed et al., 2024). Transformational Leaders create effective two-way interaction by fostering a culture of trust and mutual support, encouraging employees to engage in PEB and PWB initiatives in return for enduring relationship advantages. Social Identity Theory (SIT) also shows how employees’ identification with firms that care about the environment and sustainability makes them more committed to green projects (Ahmad et al., 2021; Raza et al., 2021) through creating a feeling of group identity and encouraging them to pursue PEB and PWB. Drawing from the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), we argue that employees’ attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control determines their intention to participate in PEB and PWB (Ahuja et al., 2023; Hasan et al., 2024). As such, leadership styles that foster employees’ pro-environmental and proactive attitudes and self-efficacy bolster intentions to engage in sustainable practices. Furthermore, the theory of self-efficacy (Bandura, 1977) posits that an individual’s confidence in his/her ability to carry out specific tasks or behaviors encourages them to engage in such activities or behaviors. Transformational leaders create an environment of observational learning and supportive feedback among employees, which enhances their self-efficacy (Fan, 2023; Walumbwa et al., 2004).

2.1. Transformational Leadership and Employees’ Psychological States (Self-Efficacy, Change-Orientation, and Positive Affect)

As conceptualized by Bass and Avolio (1994), transformational leadership encompasses four key behaviors: idealized influence, inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation, and individualized consideration. Transformational leaders create an environment of observational learning and supportive feedback among employees, which enhances their self-efficacy (Fan, 2023; Walumbwa et al., 2004). The study indicates that leadership behaviors, such as individualized consideration and inspirational motivation, are crucial in cultivating a favorable workplace climate that bolsters employees’ confidence in their capabilities (Salanova et al., 2020).

Furthermore, empirical evidence showed that transformational leadership has a direct positive impact on self-efficacy among educators, highlighting that leaders who exhibit strong transformational traits foster higher levels of self-efficacy among their teams (Warlizasusi & Ifnaldi, 2021). Likewise, Salanova et al. (2020) found that transformational leaders enhance individual self-efficacy through modeling and encouragement (Salanova et al., 2020). This development of self-efficacy is critical not only in educational settings but also extends to other professions, such as healthcare, where transformational leadership pairs with innovative self-efficacy to enhance performance (Jing et al., 2021). Additionally, the literature indicates a strong correlation between transformational leadership and self-efficacy across varied work environments. For instance, leaders instilling confidence through support and high expectations significantly uplift employees’ self-efficacy and, consequently, their job performance (Ha et al., 2024). This relationship is further supported by the view that transformational leadership enhances daily work engagement through self-efficacy and optimistic outlooks (Tims et al., 2011).

Transformational leaders inspire and motivate followers to exceed their self-interests and foster an environment conducive to change (Najihah, 2024) by promoting adaptive practices among employees, creating the organizational vision, and demonstrating care for individual team members; these leaders establish a change-friendly atmosphere that encourages employees to embrace new ideas and approaches. In this context, articulating a compelling vision and the leader’s commitment to the personal and professional growth of their team members contribute significantly to facilitating organizational change and innovation (Liu & Khong-Khai, 2024). Moreover, this style of leadership instills employees with a sense of ownership over the change process, aligning their personal goals with organizational objectives, thereby enhancing their change orientation that acts as a catalyst for internal innovation, reinforcing the positive relationship between leadership style and change-oriented behaviors (Jayson et al., 2024). Moreover, transformational leaders can enhance employees’ work engagement by fostering robust perceptions of leadership and encouraging optimism in the workplace (Tims et al., 2011). The higher the employee engagement, the more likely they are to contribute effectively to organizational change efforts (Mariah et al., 2023; Howell & Avolio, 1993).

Transformational leadership plays a beneficial role in fostering positive emotional states among employees through a shared vision and deep emotional connections. This leadership style has been associated with increased employee commitment, satisfaction, and performance, contributing to an overall enhancement of positive affect in the workplace (Anwar et al., 2023). Transformational leaders enhance employees’ emotional labor through increased psychological empowerment, which can elevate positive feelings within work contexts (Chaubey et al., 2019). Additionally, the interaction between transformational leadership and employee well-being often fosters environments characterized by deep emotional connections and support, thereby reducing burnout and enhancing positive feelings among employees (Arnold et al., 2015). These leaders create psychologically safe environments that encourage open expression and emotional sharing, which is essential for enhancing positive affect (Grošelj et al., 2020). Therefore, transformational leadership is posited to have positive implications for employees’ self-efficacy, change orientation, and positive affect by instilling confidence, promoting adaptive behaviors toward change, and enhancing employee morale. Thus, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1a.

Transformational leadership is positively associated with self-efficacy.

Hypothesis 1b.

Transformational leadership is positively associated with change orientation.

Hypothesis 1c.

Transformational leadership is positively associated with positive affect.

2.2. Transformational Leadership and Perceived Organizational Support

Transformational leadership significantly impacts perceived organizational support, which subsequently fosters knowledge-sharing behaviors grounded in the principles of social exchange theory (L. Chen et al., 2024; C.-J. Wang, 2022), where employees are likely to feel valued and appreciated in such an environment. Adequate leader support significantly enhances employees’ perception of their work environment, augmenting perceived organizational support and enabling them to pursue creativity and innovation (Cheung & Wong, 2011). Moreover, empirical evidence showed that transformational leadership behaviors positively correlate with perceived organizational support and organizational identity, such that effective transformational leaders are critical in shaping employees’ perceptions of support due to their emphatic leadership style (Liu & Khong-Khai, 2024; Dinç et al., 2022). In industries where employee engagement is paramount, such as healthcare and education, studies have demonstrated that transformational leadership fosters an environment where perceived organizational support is significantly elevated, leading to improved job satisfaction and reduced employee turnover intentions (Nguyen et al., 2025). For instance, specific leadership dimensions within transformational leadership have profound implications on employees’ perceptions of support, influencing their retention and overall job satisfaction metrics (Pattali et al., 2024). Therefore, the consistent findings across various sectors underline the importance of nurturing transformational leadership practices to enhance employee perceptions of organizational support, which, in turn, can lead to improved organizational outcomes and employee engagement. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2.

Transformational leadership is positively associated with perceived organizational support.

2.3. Employees’ Psychological States Impacting Pro-Environmental Work Behavior

Self-efficacy plays a crucial role in translating leadership influence into actual pro-environmental behaviors (Faraz et al., 2021; Mughal et al., 2022). Research indicates that leaders who exhibit transformational leadership can enhance their subordinates’ self-efficacy, fostering pro-environmental workplace actions (Y.-S. Chen et al., 2014; Robertson & Barling, 2013). Transformational leaders who exhibit environmentally specific behaviors can inspire and empower their followers, enhancing their self-efficacy regarding environmental initiatives (Cai et al., 2020; Miller et al., 2022). When employees have high environmental self-efficacy, they are more inclined to engage in pro-environmental behaviors because they feel capable of contributing to environmental sustainability (Ahuja et al., 2023; Graves et al., 2013). Therefore, by fostering an environment that supports skill development and confidence in environmental tasks, transformational leaders can effectively mediate the relationship between their leadership style and employees’ engagement in pro-environmental actions. Transformational leaders foster a heightened sense of responsibility by embedding environmental values in the organization and encouraging employees to take ownership of sustainability goals (Mansoor & Wijaksana, 2023; Robertson & Barling, 2013). Through inspirational motivation and ethical role modeling, these leaders help employees internalize a sense of responsibility for the organization’s environmental impact, enhancing their self-accountability (Crucke et al., 2022; Frink & Klimoski, 2004). Transformational leaders promote these psychological needs by allowing employees to pursue environmental initiatives with autonomy, offering support in developing environmental competencies, and fostering a collective vision of sustainability (Bono & Judge, 2003; Z. Li et al., 2020). When employees identify strongly with the organization’s environmental mission, they integrate environmental passion into their sense of identity (Althnayan et al., 2022; Tajfel & Turner, 2003). Similarly, when employees believe they can perform varied tasks, they are more likely to engage in proactive behavior in their environment (Martín et al., 2017).

Hypothesis 3a.

Employees’ self-efficacy positively influences pro-environmental work behavior.

Hypothesis 3b.

Employees’ change orientation positively influences pro-environmental work behavior.

Hypothesis 3c.

Employees’ positive affect positively influences pro-environmental work behavior.

2.4. Employees’ Psychological States Impacting Proactive Work Behavior

Self-efficacy fosters a proactive mindset, enabling individuals to initiate changes that enhance their work processes (Bindl & Parker, 2011). This relationship demonstrates that employees with higher self-efficacy are more inclined to pursue and implement proactive actions (Lin et al., 2014; Den Hartog & Belschak, 2012). Change orientation, which encompasses the willingness and ability to embrace and implement change within an organization, leads to increased adaptability and proactivity, which collectively enhance the capacity of employees to pursue proactive behaviors (Yuspahruddin et al., 2024; Baik et al., 2018). While change orientation can stimulate individuals’ positive reactions towards supporting change initiatives (Fugate et al., 2012) it may also be a source of psychological strain (Bordia et al., 2004). For instance, Katsaros and Tsirikas (2022) showed that positive change orientation reduces perceived change uncertainty, fostering a change-oriented approach among employees, which can enhance their proactive work capabilities. An activated and positive mood stimulates forward-thinking, indicating that employees who experience high levels of positive affect are more likely to engage in proactive behaviors due to the drive and energy derived from their emotional state (Bindl et al., 2012; Caniëls & Baaten, 2018). Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4a.

Employees’ self-efficacy positively influences proactive work behavior.

Hypothesis 4b.

Employees’ change orientation positively influences proactive work behavior.

Hypothesis 4c.

Employees’ positive affect positively influences proactive work behavior.

2.5. Perceived Organization Support Impacting Proactive Work Behavior and Pro-Environmental Work Behavior

Perceived organizational support can lead to employees’ voluntary pro-environmental behavior at work, indicating that such support aligns closely with environmental objectives (Saifulina et al., 2021). For instance, employees who feel supported are more likely to participate in initiatives that promote environmental sustainability, highlighting the influential role of organizational backing for eco-friendly conduct (Tantawi & Noviana, 2024). Employees often take the initiative to implement new ideas or improvements when encouraged by a high level of perceived support (Aslan, 2019; Kim et al., 2018). Additionally, employees’ pro-environmental behavioral intentions are ignited by their perception of organizational support for such initiatives (Wut & Ng, 2022). Similarly, when employees feel supported by their organization, it can lead to increased motivation to engage in proactive behaviors, which are characterized by self-initiated and change-oriented actions aimed at improving work conditions or processes (Kurtessis et al., 2015; Klimchak et al., 2016). For instance, perceived organizational support mitigates negative influences on mood, thereby fostering engagement and reducing exhaustion, which is essential for exhibiting proactive behaviors (Zacher et al., 2018; Agrawal & Singh, 2021). Moreover, leadership vision and supportive environments can significantly enhance employees’ proactive actions (Shi & Cao, 2022).

Furthermore, higher engagement—fueled by perceived support—translates into an increased willingness to act proactively, which is particularly crucial in challenging environments, as indicated during the COVID-19 pandemic, where perceived support was noted as pivotal in maintaining employee morale and proactivity (Alshaabani et al., 2021). Therefore, when employees perceive high levels of support from their organization, they are more likely to engage in proactive work behaviors and pro-environmental behavior. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 5a.

Perceived organizational support positively influences pro-environmental work behavior.

Hypothesis 5b.

Perceived organizational support positively influences proactive work behavior.

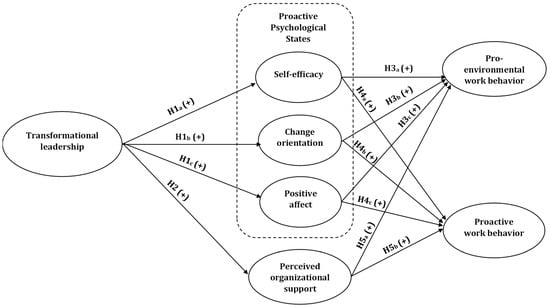

Figure 1 shows the proposed connections between the study variables. Transformational leadership (TL) is proposed to improve three essential employee psychological states: self-efficacy (SE), change orientation (CO), and positive affect (PA), in addition to perceived organizational support (POS). Every arrow from TL to these factors shows an expected positive effect since leaders help others feel confident, flexible, happy, and supported. Consequently, SE, CO, and PA are anticipated to exert a beneficial impact on both pro-environmental work behavior (PEB) and proactive work behavior (PWB). Likewise, POS is expected to positively influence PEB and PWB. The arrows from the psychological states and POS to the outcome variables show the theorized ways that TL leads to mediated sustainable and proactive behaviors. These linkages illustrate the framework’s logic: transformational leaders influence employees’ internal psychological resources and employee perceptions of organizational support, which in turn stimulate environmentally responsible and self-initiated activities in the workplace.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model.

3. Methods

3.1. Sample

Data were obtained from the working individuals in the United States employing Amazon Mechanical Turk. Respondents were from different organizations, industries, states, and regions, which may represent a diverse workforce (Buhrmester et al., 2011/2016; Peer et al., 2014). The survey data were collected during the period from 8 May 2024 to 17 May 2024. The survey participants received monetary incentives for participating in the survey.

Several design measures were implemented to ensure the quality and reliability of the collected data. Firstly, survey items were randomized to minimize response bias, and five attention check questions (e.g., Please respond “Strongly disagree”) were included in the survey to ensure that participants carefully read and consider each item. To enhance data quality and ensure the integrity of the responses, we incorporated several advanced validation techniques via Qualtrics. First, Google’s Invisible reCaptcha technology was employed to detect and prevent the participation of bots and other automated entries (https://developers.google.com/recaptcha/, accessed on 1 May 2024). This system operates in the background, assessing behavioral cues to distinguish between human and non-human respondents, reducing the risk of fraudulent responses, and ensuring only legitimate participants complete the survey. Additionally, Imperium’s ID validation technology was used to further enhance the reliability of the data by verifying respondent identities and preventing duplicate submissions (https://www.imperium.com/rlevantid/, accessed on 1 May 2024). This technology cross-references respondent information, flags potential fraud, and ensures each participant is unique, minimizing the likelihood of multiple or false entries. Out of 1120 survey responses, 450 responses were flagged as potential duplicates, and 54 responses were detected as potential bots. The remaining 666 survey responses (59% of total responses) were further screened with the attention check questions and only 542 responses passed all the quality checks.

3.2. Sample Demographics

42% of the respondents were between 30 and 39 years old, and 32% were between 21 and 29. Of the respondents, 44% were male, and 16% were female, whereas 32% of the respondents preferred not to answer this survey question. Regarding racial composition, the majority were White (97%), followed by Asian American (2%), and the remaining respondents identified as other racial groups. Regarding the education level of respondents, 48 percent had a bachelor’s degree, 23 percent had an associate degree, and 11% had a high school degree. Married respondents represent 43% of the sample, whereas 24% were unmarried. Furthermore, the study sample exhibited the highest representation in construction and real estate.

3.3. Measures

Below are definitions of constructs, scales used to measure them, and item examples.

3.3.1. Transformational Leadership

Transformational leadership is measured by seven items (Carless et al., 2000), and an example item of it is “My leader communicates a clear and positive vision of the future.”

3.3.2. Self-Efficacy

The self-efficacy construct consists of seven items (Parker et al., 2006), and an example of it is “How confident would you feel presenting information to a group of colleagues?”.

3.3.3. Change Orientation

Change orientation is measured by five items (Parker et al., 2006), and an example item is “I tried and tested ways of doing things are usually the best.”

3.3.4. Positive Affect

Positive affect is measured by ten items (Parker et al., 2006), and an example item is “Indicate to what extent you have felt excited at your work.”

3.3.5. Pro-Environmental Work Behavior

Pro-environmental work behavior is measured by seven psychometric items (Robertson & Barling, 2013), and an example item is “I make suggestions about environmentally friendly practices to managers and/or environmental committees to increase my organization’s environmental performance.”

3.3.6. Proactive Work Behavior

Proactive work behavior is measured by twelve items (Parker & Collins, 2010), and an example item is “How frequently do you try to bring about improved procedures in your workplace?”.

3.3.7. Control Variables

We used education, gender, race, and industries as control variables. Empirical evidence suggests that higher education levels correlate positively with proactive attitudes through curricular and co-curricular activities (Q. Wang et al., 2022). Transformational leaders’ influence can vary significantly across gender lines (Zeng et al., 2020). Race can also shape an individual’s ethnoracial identity, impacting perceptions of environmental issues and organizational support frameworks (S. Li et al., 2022; Zainuri et al., 2022). Specific sectors, particularly those with greater environmental impacts (e.g., manufacturing, energy), may exhibit different behavioral norms influenced by industry standards and organizational culture (Choong et al., 2020). Considering these control variables can refine the impacts of transformational leadership on proactive work behavior and pro-environmental work behavior.

3.4. Data Analysis Techniques

Data analysis was conducted using partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) because PLS-SEM can reliably deal with complex model relationships (Hair et al., 2017; Lomax, 2004). WarpPLS 8.0 software was utilized for data analysis.

3.5. Model Assessment

Most of the item loadings were higher than 0.50, and items loading less than 0.50 (Hair et al., 2010; Kock, 2022). Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics and intercorrelations among the study’s latent variables, with the square roots of the AVEs shown on the diagonal. All constructs exhibit satisfactory discriminant validity, as the diagonal values (e.g., TL = 0.747, SE = 0.754) exceed the corresponding off-diagonal correlations. Transformational leadership (TL) is positively correlated with all outcome variables, including perceived organizational support (r = 0.712) and self-efficacy (r = 0.662). Positive affect (PA) is strongly related to both proactive work behavior (r = 0.692) and pro-environmental behavior (r = 0.623), highlighting its central role in influencing behavior. Overall, the correlation patterns support the hypothesized associations in the model.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and correlations of latent variables with the squared roots of AVEs.

The structural equation modeling analysis results demonstrated a well-fitting model with robust statistical properties (Table 2). The average path coefficient (APC) was 0.235 with a significance level of p < 0.001, and the average R-squared (ARS) and adjusted R-squared (AARS) values were 0.467 and 0.464, respectively, both significant at p < 0.001, indicating high explanatory power of the model. Furthermore, the Tenenhaus GoF index was 0.566, surpassing the threshold for a large effect size, thereby providing support for the global model fit (Tenenhaus et al., 2004). The average variance inflation factor (AVIF = 1.594) and the average full collinearity VIF (AFVIF = 2.012) and full collinearity VIFs (Table 3) for all the constructs (<3.3) were within acceptable ranges, confirming the absence of multicollinearity (Hair et al., 2010).

Table 2.

Model fit and quality indices.

Table 3.

Full collinearity VIFs.

All constructs showed acceptable psychometric properties. Item loadings for each construct were above 0.70, with minimal cross-loadings (<0.50), ensuring discriminant validity (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). The indicators for transformational leadership, self-efficacy, change orientation, positive affect, pro-environmental work behavior (PEB), and proactive work behavior (PWB) all showed strong item-level contributions to their respective latent variables. Table 4 shows composite reliability, Cronbach’s alpha, and Dijkstra’s PLSc reliability, where all the values are above 0.60, which confirms that the instrument effectively captured the intended constructs with sufficient convergent and discriminant validity (Hair et al., 2010). These findings reinforce the internal reliability and structural integrity of the measurement model.

Table 4.

Constructs’ reliability.

3.6. Common Method Bias

This study utilized ex ante and ex post measures to assess common technique bias. This study employed the following ex ante measures: (a) item order randomization (Loiacono & Wilson, 2020), (b) attention check questions (Jordan & Troth, 2020), and (c) using scales with well established psychometric properties (Rubenstein et al., 2020). This study employed Harman’s single-factor test as a retrospective assessment. One factor accounts for 31.50% (<50%) of the variance in Harman’s single-factor test (Podsakoff et al., 2003). This study employed full collinearity variance inflation factors (VIF) to assess common technique bias. The findings indicated that all VIF values were below the 3.3 threshold, ranging from 1.99 to 3.28 (Cenfetelli & Bassellier, 2009). The design of the questionnaire, data collection methodologies, Harman’s test, and VIF results suggest that common method bias was not a serious issue.

4. Results

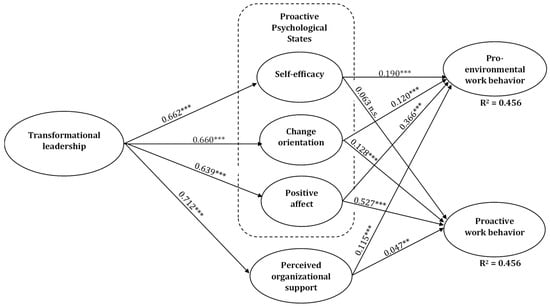

Figure 2 shows the conceptual model with data analysis results and Table 5 presents the hypothesis test results, showing path coefficients, confidence intervals, and effect sizes.

Figure 2.

Conceptual model with results. Note: n.s., non-significant association; *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, significant association.

Table 5.

Path coefficients, 95% confidence intervals (C.I.), effect sizes, and total effects.

Consistent with expectations, transformational leadership showed significant positive effects on the psychological mechanisms of employees. Specifically, transformational leadership was strongly associated with self-efficacy (β = 0.662, p < 0.001), change orientation (β = 0.660, p < 0.001), and positive affect (β = 0.639, p < 0.001). Thus, H1a, H1b, and H1c were supported. The results also revealed that the effect of transformational leadership on perceived organizational support is positive and statistically significant (β = 0.712, p < 0.001). So, H2 is also supported. The effect size of the relationship paths from transformational leadership to self-efficacy, change orientation, positive affect, and perceived organizational support indicate strong effects according to conventional benchmarks (Cohen, 2013) and align with earlier studies emphasizing the substantial role of leadership in shaping employees’ psychological resources (e.g., Salanova et al., 2020; Walumbwa et al., 2004). So, transformational leadership has a strong impact on employees’ psychological states and perceived organizational support.

Regarding outcome behaviors, the study found that employee psychological states significantly predicted pro-environmental behavior. Self-efficacy (β = 0.190, p < 0.001), change orientation (β = 0.120, p = 0.002), and positive affect (β = 0.366, p < 0.001) were all positively related to PEB. Thus, H3a, H3b, and H3c are supported. However, the effect of psychological states on proactive work behavior is partially supported. The impacts of change orientation (β = 0.128, p < 0.001) and positive affect (β = 0.527, p < 0.001) on proactive work behavior are positive and significant. However, the effect of self-efficacy on proactive work behavior is nonsignificant (β = 0.063, p < 0.071). Thus, H4b and H4c are supported, but H4a is not supported. The effect size of these relationships indicates that positive affect has stronger influence on PEB and PWB as compared to those of self-efficacy and change orientation.

The effect of perceived organizational support on pro-environmental work behavior is positive and significant (β = 0.115, p = 0.004), whereas the effect on proactive work behavior is nonsignificant. So, H5a is supported, but H5b is not supported. However, POS’s effects on PEB and PWB are small. It indicates that leadership influence is more prominent though employees’ psychological states than through perceived organizational support.

5. Discussion

5.1. Discussion of Results

These results align with theoretical and empirical research suggesting that transformational leaders foster employee confidence, adaptability, and emotional energy by articulating a compelling vision, offering individualized support, and promoting intellectual stimulation (Bass & Avolio, 1994; Walumbwa et al., 2004; Salanova et al., 2020). Furthermore, transformational leadership was positively associated with perceived organizational support, supporting the argument that such leaders cultivate a workplace climate characterized by trust, care, and acknowledgment (Kurtessis et al., 2015; L. Chen et al., 2024).

Regarding outcome behaviors, the study found that employee psychological states significantly predicted pro-environmental behavior. Self-efficacy, change orientation, and positive affect were all positively related to PEB, in line with earlier findings that these constructs contribute to employees’ motivation to engage in environmentally beneficial actions (Robertson & Barling, 2013; Bindl & Parker, 2011; Bandura, 1977). For proactive work behavior, positive affect emerged as the strongest predictor (β = 0.527, p < 0.001), followed by change orientation (β = 0.128, p = 0.001). In contrast, the effect of self-efficacy was not supported. These findings suggest that while cognitive and affective resources generally drive proactive engagement, positive emotional energy may be particularly salient in initiating self-directed and future-focused workplace actions (Caniëls & Baaten, 2018; Bindl et al., 2012).

Finally, perceived organizational support showed a significant positive relationship with pro-environmental work behavior (β = 0.115, p = 0.004), corroborating studies that underscore the importance of organizational climate in shaping sustainability-related actions among employees (Saifulina et al., 2021; Tantawi & Noviana, 2024). However, the association between POS and proactive work behavior (β = 0.047, p = 0.135) was not statistically significant. These results suggest that while POS reinforces environmentally aligned behavior, proactive behavior might be more strongly influenced by intrinsic psychological states than extrinsic support mechanisms (Zacher et al., 2018; Shi & Cao, 2022). These findings offer nuanced insights into how leadership and support mechanisms interact with employee psychology to drive meaningful behavior in organizational settings.

5.2. Theoretical Implications

This study advances theoretical understanding by illustrating how transformational leadership fosters pro-environmental and proactive behaviors through psychological pathways such as self-efficacy, change orientation, and positive affect. Prior work has emphasized leadership’s motivational role (Bass & Avolio, 1994; Walumbwa et al., 2004), yet our findings emphasize psychological states as central mediators in translating leadership influence into sustainability-related outcomes. Furthermore, the nonsignificant effect of perceived organizational support on proactive behavior suggests that intrinsic psychological resources may exert a more decisive influence than external support mechanisms (Zacher et al., 2018; Shi & Cao, 2022), calling for refinement of existing leadership-behavior models to capture individual-level drivers better.

5.3. Practical Implications

For practitioners, the findings emphasize the importance of developing leadership interventions that bolster employees’ confidence, adaptability, and emotional energy to promote sustainability. First, training initiatives should prioritize the cultivation of psychological resources—specifically, self-efficacy, change orientation, and positive affect—by incorporating experiential learning modules such as role-playing, simulation exercises, and scenario-based workshops that challenge employees to take initiative in dynamic or sustainability-oriented contexts. Second, leadership development curricula should include targeted modules on emotional intelligence and motivational communication, enabling leaders to inspire positive affect and enthusiasm among their teams. Third, organizations can implement structured feedback systems and coaching frameworks that encourage leaders to provide individualized support and intellectual stimulation, both of which have been shown to activate internal psychological mechanisms linked to pro-environmental and proactive work behavior. Finally, given the limited effect of perceived organizational support on proactive behavior, leadership interventions should emphasize fostering intrinsic motivation through recognition systems and autonomy-supportive practices rather than relying solely on external rewards or top-down directives. Collectively, these strategies can help build leadership capabilities that translate vision into sustained employee-driven action for organizational and environmental impact. Therefore, leaders should focus on enhancing psychological enablers such as positive affect and change orientation, which have strongly influenced pro-environmental and proactive behaviors (Bindl & Parker, 2011; Parker et al., 2006). While organizational support contributes to pro-environmental work, its limited impact on proactive behavior highlights the need for internal motivation–oriented strategies, including practical training and empowerment initiatives (Caniëls & Baaten, 2018; Bandura, 1977).

5.4. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

Although this study provides valuable insights, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the data were collected using Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk). While offering access to a diverse workforce, it may not reflect the behavioral variances due to firm-level factors such as organizational support and procedural justice. One concern is participant attentiveness, as MTurk workers may multitask or respond hastily to maximize compensation (Hauser & Schwarz, 2016). Additionally, MTurk samples may not fully represent the general population, often skewing toward younger, more educated, and more technologically literate individuals (Buhrmester et al., 2011/2016). To mitigate these concerns, we implemented attention check questions, a minimum response time per item of six seconds, and filtered for high-reputation workers; nonetheless, findings should be interpreted with caution due to some inherent limitations.

Second, respondents were drawn quasi-randomly from different organizations, industries, states, and regions of the United States. Hence, the sample of this study may be more representative than studies based on samples from one or few organizations or on small geographical areas. On the other hand, results are not organization specific, but they provide an overall country-wide picture of the set of organizational relationships studied thereby contributing to the generalizability of the results.

Third, the cross-sectional nature of this study may limit its ability to draw definitive causal conclusions. While the relationships between transformational leadership and the mediating variables of self-efficacy, change orientation, and positive affect are well-supported by theory, future research would benefit from a longitudinal design to better capture how these relationships evolve and how leadership behaviors influence environmental outcomes in the long term.

Fourth, the survey respondents were diverse in terms of gender, marital status, and industries, but skewed with a high proportion of white respondents. Prior studies found significant influence of race on individuals’ environmental concerns (Newell & Green, 1997) and pro-environmental behavior (Lazri & Konisky, 2019). Therefore, these study results should be interpreted considering the racial impacts on pro-environmental behavior.

Fifth, this study relied exclusively on self-reported measures to assess proactive and pro-environmental behaviors, which introduces the potential for social desirability bias and may not accurately reflect actual workplace behavior (Podsakoff et al., 2003). While self-reports are common in behavioral research and offer insights into individual perceptions and intentions, they can overestimate the frequency or intensity of desirable actions (Donaldson & Grant-Vallone, 2002). Future studies should incorporate multi-source data—such as supervisor ratings, peer assessments, or behavioral observations—to enhance the validity of findings and better capture enacted behaviors in organizational contexts.

Sixth, while this research supported environmental self-efficacy, change orientation, and positive affect as mediating variables, future studies could explore other potential mediators, such as environmental mindfulness or organizational identification, to provide a more comprehensive view of how transformational leadership fosters pro-environmental behaviors. Examining multiple mediators will further clarify the complex pathways through which leadership influences sustainability efforts.

Seventh, while traditional mediators like employees’ psychological states and perceived organizational support play significant roles in linking transformational leadership to pro-environmental and proactive work behaviors, different factors such as environmental passion (Z. Li et al., 2020), goal clarity (Peng et al., 2020), moral reflectiveness (Afsar & Umrani, 2019), leadership integrity (Crucke et al., 2022), and connectedness to nature (H. Wang et al., 2022) also demonstrably contribute to this dynamic. Future research may explore these mediators to enhance our understanding of how transformational leadership influence sustainable work behavior. Some relationships were positive and strong, most relationships were significant, and outcome variables’ coefficients of determination were reasonable, like in most models, there are, no doubt, omitted variables that may influence the relationships investigated.

6. Conclusions

The findings of this study suggest that transformational leadership have strong positive influence on employees’ psychological states (self-efficacy, change orientation, and positive affect). Transformational leadership is also positively related to perceived organizational support. Therefore, we found statistical support for transformational leadership’s positive impacts on employees’ psychological states and perceived organizational support. This study shows that employee psychological states played a vital mediator role on the relationships of transformational leadership with PEB and PWB. The relationships of transformational leadership as well as those of positive affect were positive and strong, whereas most of those of self-efficacy and change orientation had small effect sizes. However, the influence of self-efficacy and perceived organizational support on proactive work behavior was not significant. The influences of change orientation and self-efficacy on proactive work behavior were significant although weak.

This study points out the critical role of leadership in cultivating sustainability-oriented workplace behaviors via psychological mechanisms. By demonstrating the predictive power of self-efficacy, change orientation, and positive affect, the research highlights internal resources as key levers for behavioral engagement. Furthermore, the differentiated influence of perceived organizational support suggests that internal states often outweigh contextual support in driving proactive efforts. These insights contribute to refining leadership models and guiding practical interventions for sustainable organizational transformation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.R.I., L.P. and M.F.T.; methodology, M.R.I.; software, M.R.I.; validation, M.R.I., L.P. and M.F.T.; formal analysis, M.R.I.; investigation, L.P. and M.F.T.; resources, M.R.I., L.P. and M.F.T.; data curation, M.R.I.; writing—original draft preparation, M.R.I.; writing—review and editing, L.P. and M.F.T.; visualization, M.R.I., L.P. and M.F.T.; supervision, L.P.; project administration, L.P.; funding acquisition, L.P. and M.F.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding and The APC was funded by L.P. and M.F.T.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board at Texas A&M International University (protocol code 2024-02-12 and date 12 February 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

The research project fit the IRB exempt category 2 criteria as described below:

- CATEGORY 2: Research that only includes interactions involving educational tests (cognitive, diagnostic, aptitude, achievement), survey procedures, interview procedures, or observation of public behavior (including visual or auditory recording) if at least one of the following criteria is met [45 CFR 46.104(d)(2)]:

- The information obtained is recorded by the investigator in such a manner that the identity of the human subjects cannot readily be ascertained, directly or through identifiers linked to the subjects;

- Any disclosure of the human subjects’ responses outside the research would not reasonably place the subjects at risk of criminal or civil liability or be damaging to the subjects’ financial standing, employability, educational advancement, or reputation; or

- The information obtained is recorded by the investigator in such a manner that the identity of the human subjects can readily be ascertained, directly or through identifiers linked to the subjects, and an IRB conducts a limited IRB review to make the determination required by §46.111(a)(7).

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in Texas Data Repository at https://doi.org/10.18738/T8/4XNOMY.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Afsar, B., Cheema, S., & Javed, F. (2018). Activating employee’s pro-environmental behaviors: The role of CSR, organizational identification, and environmentally specific servant leadership. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 25(5), 904–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsar, B., & Umrani, W. A. (2019). Corporate social responsibility and pro-environmental behavior at workplace: The role of moral reflectiveness, coworker advocacy, and environmental commitment. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 27(1), 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, S., & Singh, S. (2021). Predictors of subjective career success amongst women employees: Moderating role of perceived organizational support and marital status. Gender in Management an International Journal, 37(3), 344–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S., Islam, T., Sadiq, M., & Kaleem, A. (2021). Promoting green behavior through ethical leadership: A model of green human resource management and environmental knowledge. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 42(4), 531–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, J., Yadav, M., & Sergio, R. P. (2023). Green leadership and pro-environmental behaviour: A moderated mediation model with rewards, self-efficacy and training. International Journal of Ethics and Systems, 39(2), 481–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshaabani, A., Naz, F., Magda, R., & Rudnák, I. (2021). Impact of perceived organizational support on OCB in the time of COVID-19 pandemic in hungary: Employee engagement and affective commitment as mediators. Sustainability, 13(14), 7800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Althnayan, S., Alarifi, A., Bajaba, S., & Alsabban, A. (2022). Linking environmental transformational leadership, environmental organizational citizenship behavior, and organizational sustainability performance: A moderated mediation model. Sustainability, 14(14), 8779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, S., Qambrani, I., Shah, N. A., & Mukarram, S. (2023). Transformational leadership and employees’ performance: The mediating role of employees’ commitment in private banking sectors in Pakistan. Liberal Arts and Social Sciences International Journal (Lassij), 7(1), 120–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, K. A., Connelly, C. E., Walsh, M. M., & Ginis, K. A. M. (2015). Leadership styles, emotion regulation, and burnout. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 20(4), 481–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asbari, M. (2020). Is transformational leadership suitable for future organizational needs? International Journal of Social, Policy and Law, 1(1), 51–55. [Google Scholar]

- Aslan, H. (2019). Mediating role of perceived organizational support in inclusive leadership’s effect on innovative work behavior. Business and Management Studies an International Journal, 7(5), 2945–2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baik, S. J., Song, H. D., & Hong, A. J. (2018). Craft your job and get engaged: Sustainable change-oriented behavior at work. Sustainability, 10(12), 4404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., Hetland, J., Olsen, O. K., & Espevik, R. (2023). Daily transformational leadership: A source of inspiration for follower performance? European Management Journal, 41(5), 700–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bass, B. M., & Avolio, B. J. (1994). Transformational leadership and organizational culture. The International Journal of Public Administration, 17(3–4), 541–554. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40862298 (accessed on 1 May 2024). [CrossRef]

- Bindl, U. K., & Parker, S. K. (2011). Proactive work behavior: Forward-thinking and change-oriented action in organizations. In S. Zedeck (Ed.), APA handbook of industrial and organizational psychology, Vol. 2. Selecting and developing members for the organization (pp. 567–598). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindl, U. K., Parker, S. K., Totterdell, P., & Hagger-Johnson, G. (2012). Fuel of the self-starter: How mood relates to proactive goal regulation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(1), 134–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiral, O., Talbot, D., & Paillé, P. (2015). Leading by example: A model of organizational citizenship behavior for the environment. Business Strategy and the Environment, 24(6), 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bono, J. E., & Judge, T. A. (2003). Self-concordance at work: Toward understanding the motivational effects of transformational leaders. Academy of Management Journal, 46(5), 554–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordia, P., Hunt, E., Paulsen, N., Tourish, D., & DiFonzo, N. (2004). Uncertainty during organizational change: Is it all about control? European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 13(3), 345–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhrmester, M., Kwang, T., & Gosling, S. D. (2016). Amazon’s mechanical turk: A new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality data? In A. E. Kazdin (Ed.), Methodological issues and strategies in clinical research (4th ed., pp. 133–139). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/14805-009. (Reprinted from “Amazon’s mechanical turk: A new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality, data?” 2011, American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 6[1], 3–5). [Google Scholar]

- Cai, W., Yang, C., Bossink, B. A. G., & Fu, J. (2020). Linking leaders’ voluntary workplace green behavior and team green innovation: The mediation role of team green efficacy. Sustainability, 12(8), 3404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caniëls, M. C., & Baaten, S. M. J. (2018). How a learning-oriented organizational climate is linked to different proactive behaviors: The role of employee resilience. Social Indicators Research, 143(2), 561–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carless, S. A., Wearing, A. J., & Mann, L. (2000). A short measure of transformational leadership. Journal of Business and Psychology, 14, 389–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenfetelli, R. T., & Bassellier, G. (2009). Interpretation of formative measurement in information systems research. MIS Quarterly, 33(4), 689–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaubey, A., Sahoo, C. K., & Khatri, N. (2019). Relationship of transformational leadership with employee creativity and organizational innovation. Journal of Strategy and Management, 12(1), 61–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L., Chang, Y. C., & Tian, Q. (2024). The mediating role of perceived organizational support in the relationship between transformational leadership and knowledge sharing behavior of university teachers in universities. Sage Open, 14(4), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-S., Chang, C.-H., & Lin, Y.-H. (2014). Green transformational leadership and green performance: The mediation effects of green mindfulness and green self-efficacy. Sustainability, 6(10), 6604–6621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, M. F., & Wong, C. S. (2011). Transformational leadership, leader support, and employee creativity. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 32(7), 656–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choong, Y. O., Ng, L.-P., Tee, C. W., Kuar, L.-S., Teoh, S.-Y., & Chen, I. C. (2020). Green work climate and pro-environmental behaviour among academics: The mediating role of harmonious environmental passion. International Journal of Management Studies, 26, 77–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (2013). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Crucke, S., Servaes, M., Kluijtmans, T., Mertens, S., & Schollaert, E. (2022). Linking environmentally-specific transformational leadership and employees’ green advocacy: The influence of leadership integrity. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 29(2), 406–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “What” and “Why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Den Hartog, D. N., & Belschak, F. D. (2012). When does transformational leadership enhance employee proactive behavior? The role of autonomy and role breadth self-efficacy. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(1), 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinç, M. S., Zaim, H., Hassanin, M., & Alzoubi, Y. I. (2022). The effects of transformational leadership on perceived organizational support and organizational identity. Human Systems Management, 41(6), 699–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, S. I., & Grant-Vallone, E. J. (2002). Understanding self-report bias in organizational behavior research. Journal of Business and Psychology, 17(2), 245–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R., Armeli, S., Rexwinkel, B., Lynch, P. D., & Rhoades, L. (2001). Reciprocation of perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(1), 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, P. (2023). Self-efficacy on transformational leadership and work engagement: Basis for higher education institutions work productivity framework. International Journal of Research Studies in Management, 11(5), 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraz, N. A., Ahmed, F., Ying, M., & Mehmood, S. A. (2021). The interplay of green servant leadership, self-efficacy, and intrinsic motivation in predicting employees’ pro-environmental behavior. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 28(4), 1171–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frink, D. D., & Klimoski, R. J. (2004). Advancing accountability theory and practice: Introduction to the human resource management review special edition. Human Resource Management Review, 14(1), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fugate, M., Prussia, G. E., & Kinicki, A. J. (2012). Managing employee withdrawal during organizational change: The role of threat appraisal. Journal of management, 38(3), 890–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, L. M., Sarkis, J., & Zhu, Q. (2013). How transformational leadership and employee motivation combine to predict employee proenvironmental behaviors in China. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 35, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grošelj, M., Černe, M., Penger, S., & Grah, B. (2020). Authentic and transformational leadership and innovative work behaviour: The moderating role of psychological empowerment. European Journal of Innovation Management, 24(3), 677–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, K.-V., Nguyen, A. T., & Nhung, N. T. T. (2024). Exploring the influence of transformational leadership on salesperson job performance: The mediating roles of self-efficacy and creativity in vietnamese smes. International Journal of Professional Business Review, 9(3), e04015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., & Thiele, K. O. (2017). Mirror, mirror on the wall: A comparative evaluation of composite-based structural equation modeling methods. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45, 616–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed., pp. 785–785). Pearson. Available online: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/facpubs/2925/ (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Han, H., Hsu, L.-T. J., & Lee, J.-S. (2009). Empirical investigation of the roles of attitudes toward green behaviors, overall image, gender, and age in hotel customers’ eco-friendly decision-making process. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 28(4), 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, A., Zhang, X., Mao, D., Kashif, M., Mirza, F., & Shabbir, R. (2024). Unraveling the impact of eco-centric leadership and pro-environment behaviors in healthcare organizations: Role of green consciousness. Journal of Cleaner Production, 434, 139704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, D. J., & Schwarz, N. (2016). Attentive turkers: MTurk participants perform better on online attention checks than do subject pool participants. Behavior Research Methods, 48(1), 400–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howell, J. M., & Avolio, B. J. (1993). Transformational leadership, transactional leadership, locus of control, and support for innovation: Key predictors of consolidated-business-unit performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(6), 891–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, M., Nisar, Q. A., Awan, A., & Nasir, U. (2024). Environmentally specific servant leadership and workplace pro-environmental behavior: A dual mediation in context of hotel industry. Journal of Cleaner Production, 446, 141095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayson, B. D. L. S., Ignalig, W. O., & Cayogyog, A. O. (2024). Transformational leadership and organizational behavior: The mediating role of commitment to change among teachers in davao city. Ejahss, 1(3), 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, J., Niyomsilp, E., Xie, L., Jiang, H., & Li, R. (2021). Effect of transformational leadership on nursing informatics competency of chinese nurses: The intermediary function of innovation self-efficacy. IOS Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, P. J., & Troth, A. C. (2020). Common method bias in applied settings: The dilemma of researching in organizations. Australian Journal of Management, 45(1), 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsaros, K. K., & Tsirikas, A. N. (2022). Perceived change uncertainty and behavioral change support: The role of positive change orientation. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 35(3), 511–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H., Im, J., Qu, H., & Namkoong, J. (2018). Antecedent and consequences of job crafting: An organizational level approach. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 30(3), 1863–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimchak, M., Carsten, M. K., Morrell, D. L., & MacKenzie, W. I. (2016). Employee entitlement and proactive work behaviors. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 23(4), 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. (2022). WarpPLS user manual (latest version 8.0). ScriptWarp Systems. [Google Scholar]

- Kurtessis, J. N., Eisenberger, R., Ford, M. T., Buffardi, L. C., Stewart, K. A., & Adis, C. (2015). Perceived organizational support: A meta-analytic evaluation of organizational support theory. Journal of Management, 43(6), 1854–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazri, A. M., & Konisky, D. M. (2019). Environmental attitudes across race and ethnicity. Social Science Quarterly, 100(4), 1039–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S., Chen, F., & Xiao, G. (2022). Effects of group emotion and moral belief on pro-environmental behavior: The mediating role of psychological clustering. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(18), 11190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z., Xue, J., Li, R., Chen, H., & Wang, T. (2020). Environmentally specific transformational leadership and employee’s pro-environmental behavior: The mediating roles of environmental passion and autonomous motivation. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.-H., Lu, W. C., Chen, M.-Y., & Chen, L. H. (2014). Association between proactive personality and academic self–efficacy. Current Psychology, 33(4), 600–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F., & Khong-Khai, S. (2024). A comparative study of transactional and transformational leadership in the context of the digital economy. Journal of Southwest Jiaotong University, 59(2), 428–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loiacono, E., & Wilson, V. (2020). Do we truly sacrifice truth for simplicity: Comparing complete individual randomization and semi-randomized approaches to survey administration. AIS Transactions on Human-Computer Interaction, 12(2), 45–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomax, R. G. (2004). A beginner’s guide to structural equation modeling. Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mansoor, M., & Wijaksana, T. I. (2023). Predictors of pro-environmental behavior: Moderating role of knowledge sharing and mediatory role of perceived environmental responsibility. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 66(5), 1089–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariah, W., Hardjo, S., & Effendy, S. (2023). Transformational leadership and work engagement in muslim workers: The moderating role of gender. Inspira Indonesian Journal of Psychological Research, 4(1), 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, I. B., Llusar, J. C. B., Roca-Puig, V., & Tena, A. B. E. (2017). The relationship between high performance work systems and employee proactive behaviour: Role breadth self-efficacy and flexible role orientation as mediating mechanisms. Human Resource Management Journal, 27(3), 403–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, L. B., Rice, R. E., Gustafson, A., & Goldberg, M. H. (2022). Relationships among environmental attitudes, environmental efficacy, and pro-environmental behaviors across and within 11 countries. Environment and Behavior, 54(7–8), 1063–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mughal, M. F., Cai, S. L., Faraz, N. A., & Ahmed, F. (2022). Environmentally specific servant leadership and employees’ pro-environmental behavior: Mediating role of green self efficacy. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 15, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najihah, A. (2024). Molding the future: The integral role of leadership styles in shaping organizational success. Historical, 3(1), 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, S. J., & Green, C. L. (1997). Racial differences in consumer environmental concern. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 31(1), 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, G. T., Matošková, J., Pham, N. T., & Nguyen, M. T. (2025). Employee informal coaching and job performance in higher education: The role of perceived organizational support and transformational leadership. PLoS ONE, 20(4), e0320577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S. K., & Collins, C. G. (2010). Taking stock: Integrating and differentiating multiple proactive behaviors. Journal of Management, 36(3), 633–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S. K., Williams, H. M., & Turner, N. (2006). Modeling the antecedents of proactive behavior at work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(3), 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattali, S., Sankar, J. P., Qahtani, H. A., Menon, N., & Faizal, S. (2024). Effect of leadership styles on turnover intention among staff nurses in private hospitals: The moderating effect of perceived organizational support. BMC Health Services Research, 24(1), 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peer, E., Vosgerau, J., & Acquisti, A. (2014). Reputation as a sufficient condition for data quality on amazon mechanical turk. Behavior Research Methods, 46, 1023–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J., Chen, X., Zou, Y., & Nie, Q. (2020). Environmentally specific transformational leadership and team pro-environmental behaviors: The roles of pro-environmental goal clarity, pro-environmental harmonious passion, and power distance. Human Relations, 74(11), 1864–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raza, A., Farrukh, M., Iqbal, M. K., Farhan, M., & Wu, Y. (2021). Corporate social responsibility and employees’ voluntary pro-environmental behavior: The role of organizational pride and employee engagement. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 28(3), 1104–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, J. L., & Barling, J. (2013). Greening organizations through leaders’ influence on employees’ pro-environmental behaviors. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 34(2), 176–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubenstein, A. L., Kammeyer-Mueller, J., Simon, L., Corwin, E. S., Morrison, H., & Whiting, S. (2020). Evaluating various sources of common method bias and psychological separation as an alternate remedy. Academy of Management Proceedings. [Google Scholar]

- Saad Alessa, G. (2021). The dimensions of transformational leadership and its organizational effects in public universities in Saudi Arabia: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 682092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saifulina, N., Penela, A. C., & Sanmartín, E. R. (2021). The antecedents of employees’ voluntary proenvironmental behavior at work in developing countries: The role of employee affective commitment and organizational support. Business Strategy & Development, 4(3), 343–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salanova, M., Rodríguez-Sánchez, A., & Nielsen, K. (2020). The impact of group efficacy beliefs and transformational leadership on followers’ self-efficacy: A multilevel-longitudinal study. Current Psychology, 41(4), 2024–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, M. S. M., Elsayed-El, A., Elsabahy, H. E., & Ata, A. A. (2024). Leading with vision: The mediating role of organizational support in nurse interns’ creativity and organizational effectiveness. Research Square. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y., & Cao, M. (2022). High commitment work system and employee proactive behavior: The mediating roles of self-efficiency and career development prospect. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 802546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suifan, T., Abdallah, A. B., & Janini, M. A. (2018). The impact of transformational leadership on employees’ creativity. Management Research Review, 41(1), 113–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (2003). The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. Social Psychology, 4, 73–98. [Google Scholar]

- Tantawi, R., & Noviana, N. A. H. (2024). Employee green behavior’s impact on sustainable environmental performance: Exploring the mediating-moderating roles of perceived organizational support and self-efficacy. Jurnal Manajemen Dan Kewirausahaan, 12(1), 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenenhaus, M., Amato, S., & Esposito Vinzi, V. (2004, June 21–23). A global goodness-of-fit index for PLS structural equation modelling. XLII SIS Scientific Meeting, Pisa, Italy. [Google Scholar]

- Tims, M., Bakker, A. B., & Xanthopoulou, D. (2011). Do transformational leaders enhance their followers’ daily work engagement? The Leadership Quarterly, 22(1), 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walumbwa, F. O., Wang, P., Lawler, J., & Shi, K. (2004). The role of collective efficacy in the relations between transformational leadership and work outcomes. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 77(4), 515–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-J. (2022). Exploring the mechanisms linking transformational leadership, perceived organizational support, creativity, and performance in hospitality: The mediating role of affective organizational commitment. Behavioral Sciences, 12(10), 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H., Khan, M. A., Zhenqiang, J., Cismaş, L. M., Ali, M. A., Saleem, U., & Negruț, L. (2022). Unleashing the role of CSR and employees’ pro-environmental behavior for organizational success: The role of connectedness to nature. Sustainability, 14(6), 3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q., Niu, G., Gan, X., & Cai, Q. (2022). Green returns to education: Does education affect pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors in China? PLoS ONE, 17(2), e0263383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warlizasusi, J., & Ifnaldi, I. (2021). The influence of transformational leadership and self-efficacy on the performance of iain curup lecturers. Edukasi Islami Jurnal Pendidikan Islam, 9(02), 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wut, T. M., & Ng, P. (2022). Perceived CSR motives, perceived CSR authenticity, and pro-environmental behavior intention: An internal stakeholder perspective. Social Responsibility Journal, 19(5), 797–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuspahruddin, A., Abbas, H., Pahala, I., Eliyana, A., & Yazid, Z. (2024). Fostering proactive work behavior: Where to start? PLoS ONE, 19(5), e0298936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacher, H., Schmitt, A., Jimmieson, N. L., & Rudolph, C. W. (2018). Dynamic Effects of personal initiative on engagement and exhaustion: The role of mood, autonomy, and support. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 40(1), 38–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainuri, N. A., Rahman, N. A., Halim, L., Chan, M. Y., & Bazari, N. N. M. (2022). Measuring pro-environmental behavior triggered by environmental values. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(23), 16013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S., Wu, L., & Liu, T. (2020). Religious beliefs and public pro-environmental behavior in China: The mediating role of environmental risk perception. Religions, 11, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]