Selected Attributes of Human Resources Diversity Predicting Locus of Control from a Management Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

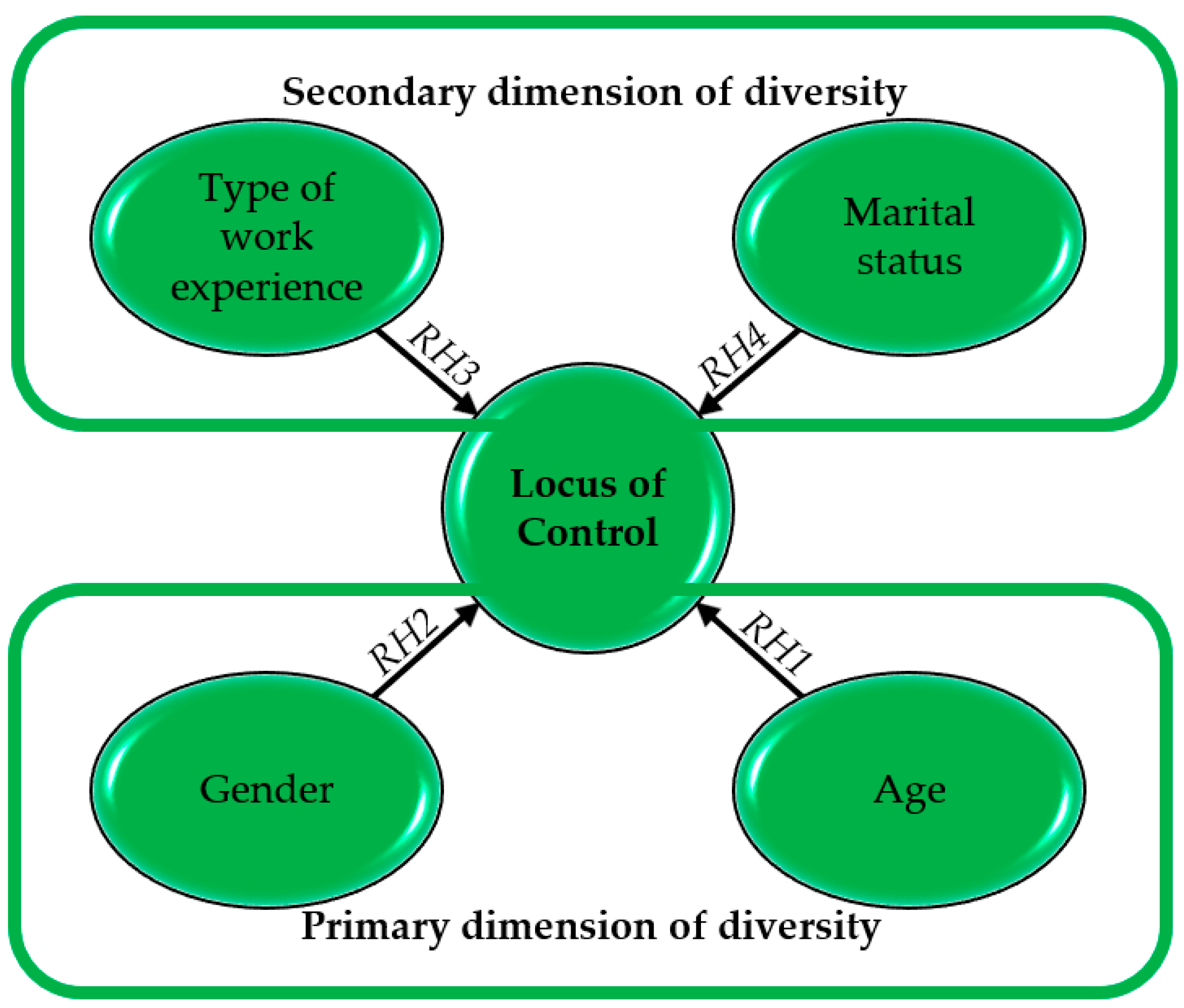

2. Theoretical Background

3. Literature Review

4. Materials and Methodology

4.1. Description of the Research Instrument and Methods Used

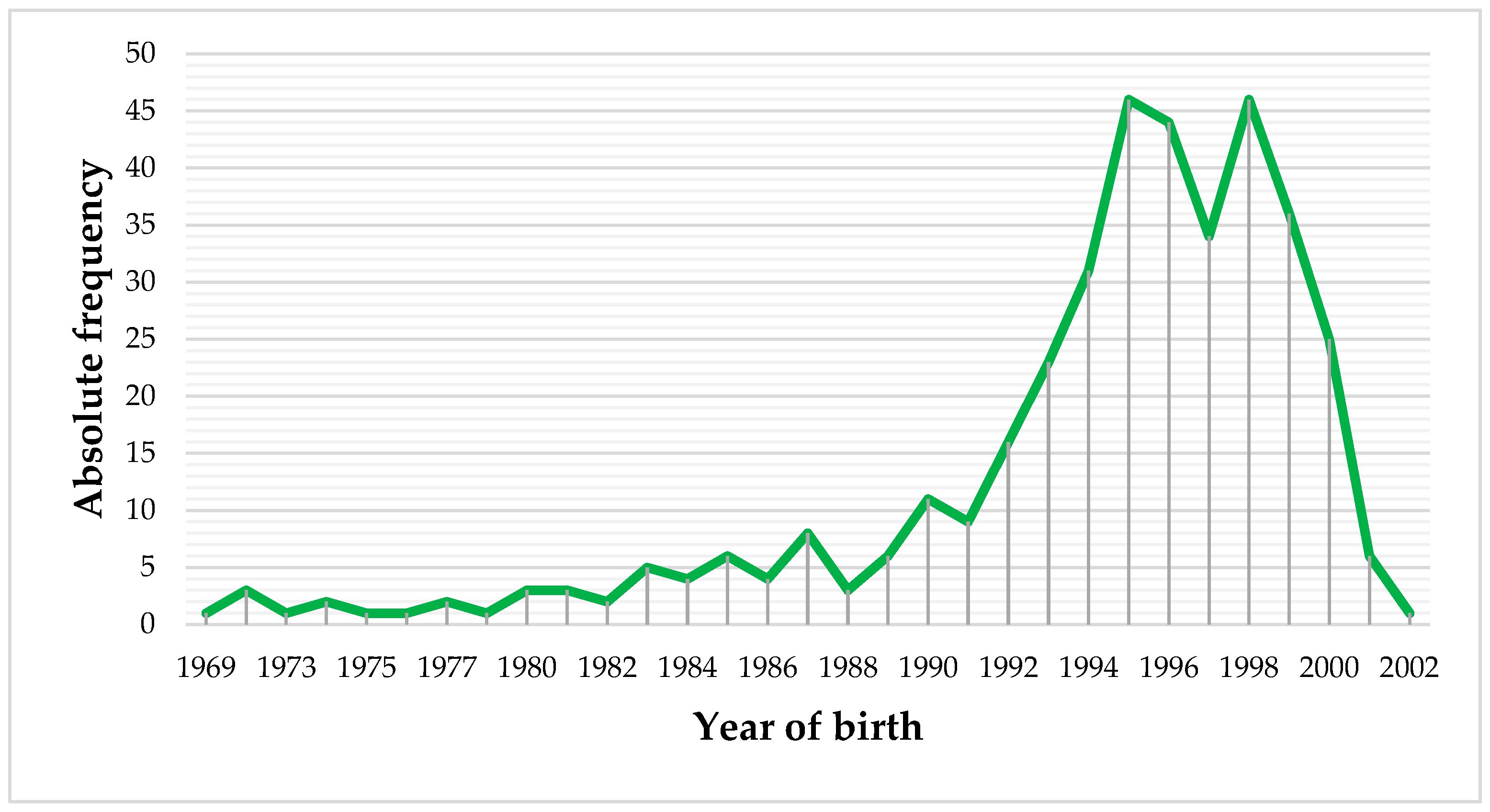

4.2. Characteristics of the Research Sample

5. Results

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahlin, E. M., & Antunes, M. J. L. (2015). Locus of control orientation: Parents, peers, and place. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44(9), 1803–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ai, A. L., Peterson, C., Rodgers, W., & Tice, T. N. (2005). Effects of faith and secular factors on locus of control in middle-aged and older cardiac patients. Aging & Mental Health, 9(5), 470–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antwi-Boasiako, B. A. (2017). It’s beyond my control: The effect of locus of control orientation on disaster insurance adoption. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 22, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arkorful, H., & Hilton, S. K. (2022). Locus of control and entrepreneurial intention: A study in a developing economy. Journal of Economic and Administrative Sciences, 38(2), 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baguma, P., & Chireshe, R. (2012). Predictors of economic locus of control among university students in Uganda. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 22(2), 279–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botha, F., & Dahmann, S. C. (2024). Locus of control, self-control, and health outcomes*. SSM-Population Health, 25, 101566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, T. M., Maillet, M. A., & Grouzet, F. M. E. (2019). Self-regulation of student drinking behavior: Strength-energy and self-determination theory perspectives. Motivation Science, 5(3), 202–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S. L., & Heo, W. (2021). Financial constraints, external locus of control, and emotional exhaustion. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 32(2), 280–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Drazic, M. C., Petrovic, I. B., & Vukelic, M. (2018). Career ambition as a way of understanding the relation between locus of control and self-perceived employability among psychology students. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duckworth, A. L., Gendler, T. S., & Gross, J. J. (2016). Situational strategies for self-control. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 11(1), 35–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falco, V. (2007). Road prevention and safety: An instrument for measuring locus of control in the social marketing perspective. TPM-Testing, Psychometrics, Methodology in Applied Psychology, 14(1), 41–61. Available online: https://www.tpmap.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/14.1.3.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Galvin, B. M., Randel, A. E., Collins, B. J., & Johnson, R. E. (2018). Changing the focus of locus (of control): A targeted review of the locus of control literature and agenda for future research. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 39(7), 820–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golding, J., Gregory, S., Ellis, G., Nunes, T., Bryant, P., Iles-Caven, Y., & Nowicki, S. (2019). Maternal prenatal external locus of control and reduced mathematical and science abilities in their offspring: A longitudinal birth cohort study. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graybill, D. (1978). Effects of perceived freedom on the relationship of locus of control beliefs to typical shifts in expectancy. Psychological Reports, 43(3), 815–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanfstingl, B., Andreitz, I., Mueller, F. H., & Thomas, A. (2010). Are self-regulation and self-control mediators between psychological basic needs and intrinsic teacher motivation? Journal for Educational Research Online-Jero, 2(2), 55–71. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, O. J., & Hartman, S. J. (1992). Organizational behavior. Best Business Books. [Google Scholar]

- Heinicke, A., Guenther, T. W., & Widener, S. K. (2016). An examination of the relationship between the extent of a flexible culture and the levers of control system: The key role of beliefs control. Management Accounting Research, 33, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henninger, D. E., Whitson, H. E., Cohen, H. J., & Ariely, D. (2012). Higher medical morbidity burden is associated with external locus of control. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 60(4), 751–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulková, V. (2024). Generačná diverzita v ošetrovateľstve—Výzva pre vzdelávanie, prax a manažment. Available online: https://www.prohuman.cz/files/Hulkov%C3%A1,2024-Genera%C4%8Dn%C3%A1-diverzita-v-o%C5%A1etrovate%C4%BEstve.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Inzlicht, M., Schmeichel, B. J., & Macrae, C. N. (2014). Why self-control seems (but may not be) limited. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 18(3), 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, A. M., Giebels, E., van Rompay, T. J. L., Austrup, S., & Junger, M. (2017). Order and control in the environment: Exploring the effects on undesired behaviour and the importance of locus of control. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 22(2), 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassianos, A. P., Symeou, M., & Ioannou, M. (2016). The health locus of control concept: Factorial structure, psychometric properties and form equivalence of the multidimensional health locus of control scales. Health Psychology Open, 3(2), 2055102916676211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaynak, H., Turan, A., & Demir, Y. (2024). Locus of control as a mediator of the relationships between motivational systems and trait anxiety. Psychological Reports, 127(4), 1533–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazén, M., & Kuhl, J. (2022). Ego-depletion or invigoration in solving the tower of Hanoi? Action orientation helps overcome planning deficits. Current Psychology, 41(4), 2469–2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knezevic, M. N., Mijatov, M., & Kovacic, S. (2021). Achievement motivation and locus of control as factors of entrepreneurial orientation in tourism and healthcare services. Journal of East European Management Studies, 26(2), 275–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C. P., & Ding, C. G. (2003). Modeling information ethics: The joint moderating role of locus of control and job insecurity. Journal of Business Ethics, 48(4), 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, T., & Hastings, R. P. (2009). Parental locus of control and psychological well-being in mothers of children with intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 34, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maadal, A. (2020). The relationship between locus of control and conformity. Journal of Cognition and Culture, 20(1–2), 100–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markovizky, M., & Shafran, Y. (2024). The deviance and relationship between locus of control, control ratio, and self-control. Sociological Inquiry, 94(3), 655–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moller, A. C., Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2006). Choice and ego-depletion: The moderating role of autonomy. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32(8), 1024–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosing, M. A., Pedersen, N. L., Cesarini, D., Johannesson, M., Magnusson, P. K. E., Nakamura, J., Madison, G., & Ullen, F. (2012). Genetic and environmental influences on the relationship between flow proneness, locus of control and behavioral inhibition. PLoS ONE, 7(11), e47958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussel, P. (2019). From needs to traits: The mediating role of beliefs about control. Personality and Individual Differences, 151, 109525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunyemi, K. (2013). Ethics education and locus of control: Is Rotter’s scale valid for Nigeria? African Journal of Business Ethics, 7(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojukwu, M. O., & Onuoha, U. D. (2012). Primary school teachers’ perception of the effectiveness of continuous assessment in Uyo Metropolis, Akwa Ibom State, Nigeria. African Research Review, 6(2), 119–133. [Google Scholar]

- Østergaard, C. R., & Timmermans, B. (2023). Workplace diversity and innovation performance: Current state of affairs and future directions. arXiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reknes, I., Visockaite, G., Liefooghe, A., Lovakov, A., & Einarsen, S. (2019). Locus of control moderates the relationship between exposure to bullying behaviors and psychological strain. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenbaum, M., & Argon, S. (1979). Locus of control and success in self-initiated attempts to stop smoking. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 35(4), 870–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rotter, J. B. (1966). Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychological Monographs, 80, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rotter, J. B. (1975). Some problems and misconceptions related to the construct of internal versus external control of reinforcement. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 43, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C. D., & Keyes, C. L. M. (1995). The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(4), 719–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakotic-Kurbalija, J., Kurbalija, D., & Mihic, J. J. I. (2017). Effects of marital locus of control on perception of marital quality among wives. Primenjena Psihologija, 10(1), 17–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schepers, J. M. (2004). Overcoming the effects of differential skewness of test items in scale construction. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 30(4), 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schepisi, C. (2024). Role of locus of control in mental health behaviours and outcomes. Dialogues in Philosophy Mental and Neuro Sciences, 17(1), 17–28. [Google Scholar]

- Shojaee, M., & French, C. (2014). The relationship between mental health components and locus of control in youth. Psychology, 5(8), 966–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stones, C. (1983). Self-determination and attribution of responsibility—Another look. Psychological Reports, 53(2), 391–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomason, J. (1983). Multidimensional assessment of locus of control and obesity. Psychological Reports, 53(3), 1083–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verwijs, C., & Russo, D. (2023). The double-edged sword of diversity: How diversity, conflict, and psychological safety impact software teams. IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering, 50, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visdómine-Lozano, J. C., & Luciano, C. (2006). Locus of control and self-regulation behaviour: Conceptual and experimental review. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 6(3), 729–751. [Google Scholar]

- Vlas, C. O., Richard, O. C., Andrevski, G., Konrad, A. M., & Yang, Y. (2022). Dynamic capabilities for managing racially diverse workforces: Effects on competitive action variety and firm performance. Journal of Business Research, 141, 600–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J. S., Lynch, C. P., Voronca, D., & Egede, L. E. (2016). Health locus of control and cardiovascular risk factors in veterans with type 2 diabetes. Endocrine, 51(1), 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W. C. H., Chen, S. X., & Ng, J. C. K. (2020). Does believing in fate facilitate active or avoidant coping? The effects of fate control on coping strategies and mental well-being. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(17), 6383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X., & Fan, G. (2016). Direct and indirect relationship between locus of control and depression. Journal of Health Psychology, 21(7), 1293–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Inner Individual (I Control My Destiny) | External Individual (Factors in My Environment Control Me) |

|---|---|

| Is more satisfied with the results of personal efforts Feel more satisfied working under a participatory leader and less satisfied with directive leadership Sees a strong relationship between personal effort and personal performance Uses personal persuasion and rewards to influence others Will be more sensitive to situations that involve individual decisions Will be more open to environmental influences Will be more considerate of the needs of others | Is less satisfied with the results of personal efforts Feels less satisfied with a participative leader is more satisfied with a directive Sees a weak relationship between personal efforts and personal performance Will use coercive power to influence others Will be less confident in individual decisions Will be more concerned with changes in the environment Will be more concerned with personal well-being than the well-being of others |

| Gender | Absolute Frequency | Relative Frequency [%] |

|---|---|---|

| Men | 199 | 51.82 |

| Women | 185 | 48.18 |

| Total | 384 | 100.00 |

| Marital Status | Absolute Frequency | Relative Frequency [%] |

|---|---|---|

| Married | 59 | 15.37 |

| Single, but in a relationship | 198 | 51.56 |

| Single, not in a relationship | 127 | 33.07 |

| Total | 384 | 100.00 |

| Employment Status | Absolute Frequency | Relative Frequency [%] |

|---|---|---|

| Employee/self-employed person | 91 | 23.70 |

| Working student | 274 | 71.35 |

| Unemployed | 19 | 04.95 |

| Total | 384 | 100.00 |

| Descriptives Statistics | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LoC | N | Mean | Std. Deviation | Std. Error | 95% Confidence Interval for Mean | Minimum | Maximum | |

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |||||||

| I | 273 | 1993.92 | 5.750 | 0.348 | 1993.24 | 1994.61 | 1969 | 2001 |

| E | 52 | 1994.38 | 6.402 | 0.888 | 1992.60 | 1996.17 | 1972 | 2002 |

| B | 59 | 1994.78 | 4.650 | 0.605 | 1993.57 | 1995.99 | 1978 | 2001 |

| Total | 384 | 1994.12 | 5.685 | 0.290 | 1993.55 | 1994.69 | 1969 | 2002 |

| Test of Homogeneity of Variances | Levene Statistic | df1 | df2 | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Based on Mean | 1.166 | 2 | 381 | 0.313 |

| Based on Median | 0.825 | 2 | 381 | 0.439 | |

| Based on Median and with adjusted df | 0.825 | 2 | 366.143 | 0.439 | |

| Based on trimmed mean | 0.963 | 2 | 381 | 0.382 | |

| ANOVA | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year of Birth | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. |

| Between Groups | 39.899 | 2 | 19.949 | 0.616 | 0.541 |

| Within Groups | 12,337.828 | 381 | 32.383 | - | - |

| Total | 12,377.727 | 383 | - | - | - |

| Result LoC/Gender | Result I—Internal Control | Result E—External Control | Result B—Balanced Control | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute Frequency | Relative Frequency [%] | Absolute Frequency | Relative Frequency [%] | Absolute Frequency | Relative Frequency [%] | |

| Men | 143 | 52.38 | 22 | 42.31 | 34 | 57.63 |

| Women | 130 | 47.62 | 30 | 57.69 | 25 | 42.37 |

| Total | 273 | 100.00 | 52 | 100.00 | 59 | 100.00 |

| Chi-Square Tests | Value | df | Asymptotic Significance (2-Sided) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pearson Chi-Square | 2.716 | 2 | 0.257 |

| Likelihood Ratio | 2.723 | 2 | 0.256 |

| Linear-by-Linear Association | 0.068 | 1 | 0.794 |

| N of Valid Cases | 384 | - | - |

| 0 cells (0.0%) have expected count less than 5. The minimum expected count is 25.05. | |||

| Result LoC/Employment Status | Result I—Internal Control | Result E—External Control | Result B—Balanced Control | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute Frequency | Relative Frequency [%] | Absolute Frequency | Relative Frequency [%] | Absolute Frequency | Relative Frequency [%] | |

| Employee/Self-employed person | 72 | 26.37 | 7 | 13.46 | 12 | 20.33 |

| Working student | 191 | 69.96 | 41 | 78.85 | 42 | 71.19 |

| Unemployed | 10 | 03.67 | 4 | 07.69 | 5 | 08.48 |

| Total | 273 | 100.00 | 52 | 100.00 | 59 | 100.00 |

| Correlations | Result LoC | Type of Work Experience | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Result LoC | Pearson Correlation | 1 | 0.354 * |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | - | 0.042 | |

| N | 384 | 384 | |

| Type of work experience | Pearson Correlation | 0.354 * | 1 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.042 | - | |

| N | 0384 | 384 | |

| Result LoC/Marital Status | Result I—Internal Control | Result E—External Control | Result B—Balanced Control | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute Frequency | Relative Frequency [%] | Absolute Frequency | Absolute Frequency | Relative Frequency [%] | Absolute Frequency | |

| Married | 40 | 14.65 | 8 | 15.38 | 11 | 18.65 |

| Single, but in a relationship | 149 | 54.58 | 20 | 38.47 | 29 | 49.15 |

| Single, not in a relationship | 84 | 30.77 | 24 | 46.15 | 19 | 32.20 |

| Total | 273 | 100.00 | 52 | 100.00 | 59 | 100.00 |

| Chi-Square Tests | Value | df | Asymptotic Significance (2-Sided) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pearson Chi-Square | 5.924 | 4 | 0.205 |

| Likelihood Ratio | 5.772 | 4 | 0.217 |

| Linear-by-Linear Association | 0.037 | 1 | 0.847 |

| N of Valid Cases | 384 | - | - |

| 0 cells (0.0%) have expected count less than 5. The minimum expected count is 7.99. | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gyurák Babeľová, Z.; Stareček, A.; Vraňaková, N. Selected Attributes of Human Resources Diversity Predicting Locus of Control from a Management Perspective. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 333. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15090333

Gyurák Babeľová Z, Stareček A, Vraňaková N. Selected Attributes of Human Resources Diversity Predicting Locus of Control from a Management Perspective. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(9):333. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15090333

Chicago/Turabian StyleGyurák Babeľová, Zdenka, Augustín Stareček, and Natália Vraňaková. 2025. "Selected Attributes of Human Resources Diversity Predicting Locus of Control from a Management Perspective" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 9: 333. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15090333

APA StyleGyurák Babeľová, Z., Stareček, A., & Vraňaková, N. (2025). Selected Attributes of Human Resources Diversity Predicting Locus of Control from a Management Perspective. Administrative Sciences, 15(9), 333. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15090333