The Role of Financial Institutions in Bridging the Financing Gap for Women Entrepreneurs in Sub-Saharan Africa

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Access to Finance: Structural and Gendered Barriers

2.2. Financial Literacy and Entrepreneurial Capability

3. Theoretical Backdrop

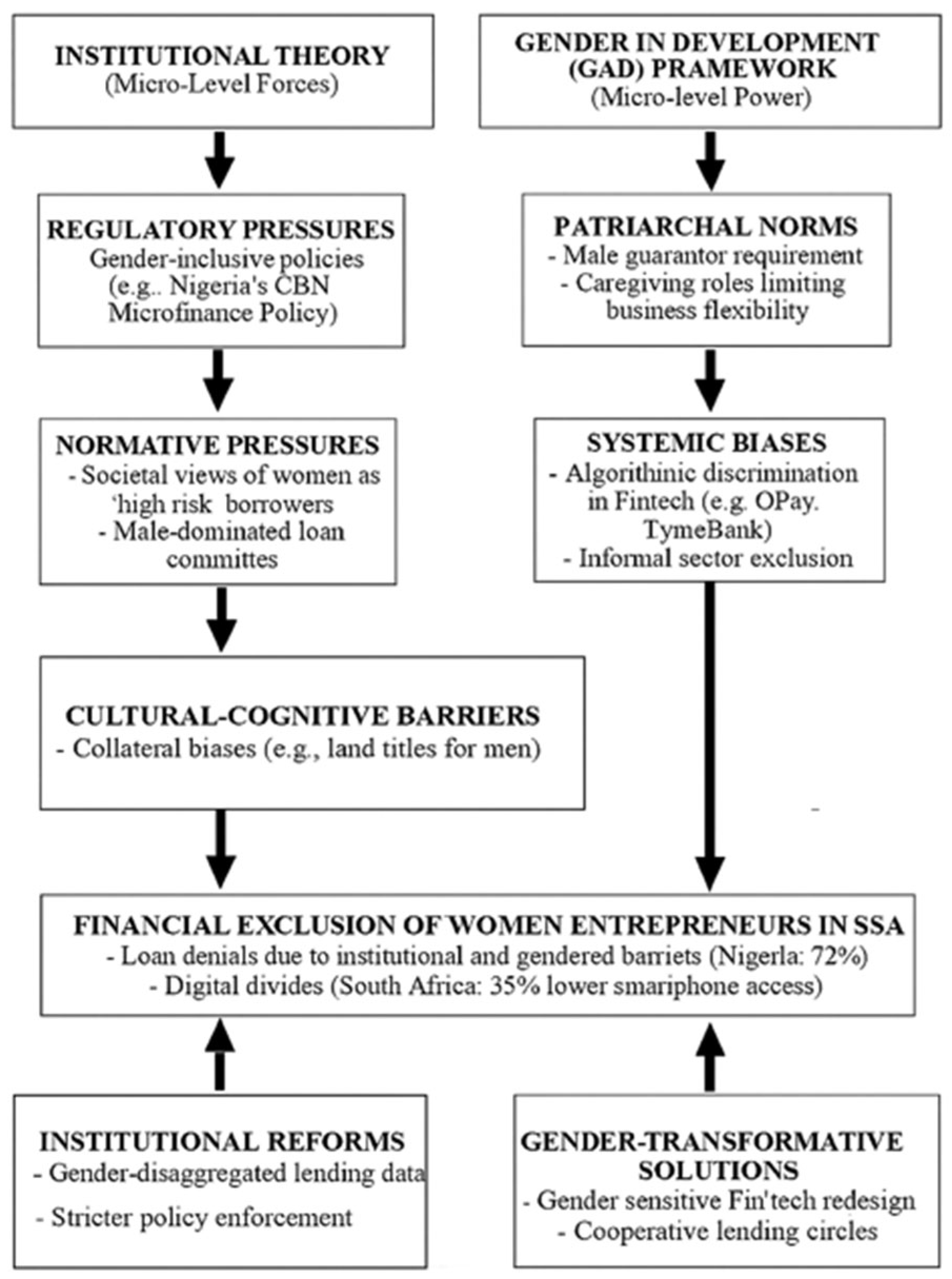

3.1. Institutional Theory: Structural Constraints and Legitimacy

- Regulatory Pressures: In Nigeria, the Microfinance Policy (Central Bank of Nigeria, 2011) and South Africa’s Women Empowerment Fund (Department of Trade and Industry, 2015) exemplify formal efforts to promote gender-inclusive finance. However, as Amine and Staub (2009) argue, weak enforcement and institutional decoupling (Meyer & Rowan, 1977) allow banks to maintain traditional risk models that disadvantage women (e.g., excessive collateral demands). Empirical studies in Nigeria reveal that 72% of women-led SMEs are denied loans due to non-compliance with rigid criteria (Imhonopi & Ugochukwu, 2013), underscoring the gap between policy intent and practice.

- Normative Pressures: Societal norms in both countries associate entrepreneurship with masculinity (Kabiru et al., 2022), leading financial institutions to unconsciously privilege male applicants. For instance, interviews with South African bankers (Peter et al., 2025) reveal perceptions of women-owned businesses as “high risk” due to their concentration in informal sectors (e.g., retail, care work).

- Cultural–Cognitive Barriers: Deep-seated biases manifest in lending practices, such as requiring male guarantors for Nigerian women (Akintola et al., 2020) or algorithmic discrimination in fintech platforms (Nguyen et al., 2021). These practices reflect what Thornton et al. (2012) term “institutional logics” that conflate creditworthiness with male-dominated financial histories.

3.2. Gender and Development (GAD) Framework

- Patriarchal Financial Systems: In Nigeria, only 15% of women hold land titles, limiting their collateral options. Similarly, South African women face repayment schedule inflexibility due to unpaid care burdens (Irene et al., 2021). These findings align with Razavi (1997)’s argument that financial systems are designed around male economic participation.

- Intersectional Marginalisation: Rural women in both countries face compounded exclusion due to digital divides (Irene et al., 2025). For example, fintech platforms like OPay (Nigeria) and TymeBank (South Africa) rely on smartphone penetration, which is 30% lower among rural women (GSMA, 2022).

- Resistance and Agency: The GAD lens highlights women’s resilience, such as Nigerian market women forming cooperative savings groups (Chilongozi, 2022). However, such informal mechanisms lack scalability, reinforcing the need for structural reforms.

3.3. Integrating the Frameworks

3.4. Hypothesis Development

3.4.1. Access to Finance

3.4.2. Collateral Requirements

3.4.3. Interest Rates and Costs

3.4.4. Financial Literacy

- 42% more likely to use formal credit (Demirgüç-Kunt et al., 2022);

- Better at negotiating interest rates and avoiding predatory loans;

- More proactive at building credit histories through strategic product usage.

3.4.5. Fintech Solutions

- Nano-loans tailored to women’s cyclical income flows;

- Group liability models using social capital as collateral;

- Dynamic repayment algorithms adjusting to seasonal businesses.

- Reducing their dependence on male guarantors;

- Providing financial autonomy through smartphone access;

- Creating data trails that build formal credit histories.

3.4.6. Government Support

3.4.7. Barriers to Financing

3.4.8. Business Growth

4. Materials and Methods

5. Results

- Access to Finance (mean = 2.21): This construct has one of the lowest mean scores (2.21 out of 5). This suggests that, overall, respondents found it difficult to access financial services. Additionally, the relatively low standard deviation (0.92) indicates fairly consistent negative experiences across respondents.

- Institutional Barriers and Collateral Requirements: The data shows that institutional barriers have one of the highest means (3.96), while collateral requirements also score high (3.76). This suggests that (a) most respondents face significant institutional obstacles and (b) collateral requirements are seen as a major hurdle. These two factors might be key bottlenecks in the financing process.

- Business Growth (mean = 3.90): The data shows a high mean score (3.90) and low standard deviation (0.54), which indicates consistent optimism. Despite financing challenges, businesses maintain a positive growth outlook.

- Government Support: The data shows that this construct has the second-lowest mean (2.37) and a relatively high standard deviation (0.92). This indicates a generally poor perception of government support, but experiences vary significantly.

5.1. Inferential Statistics

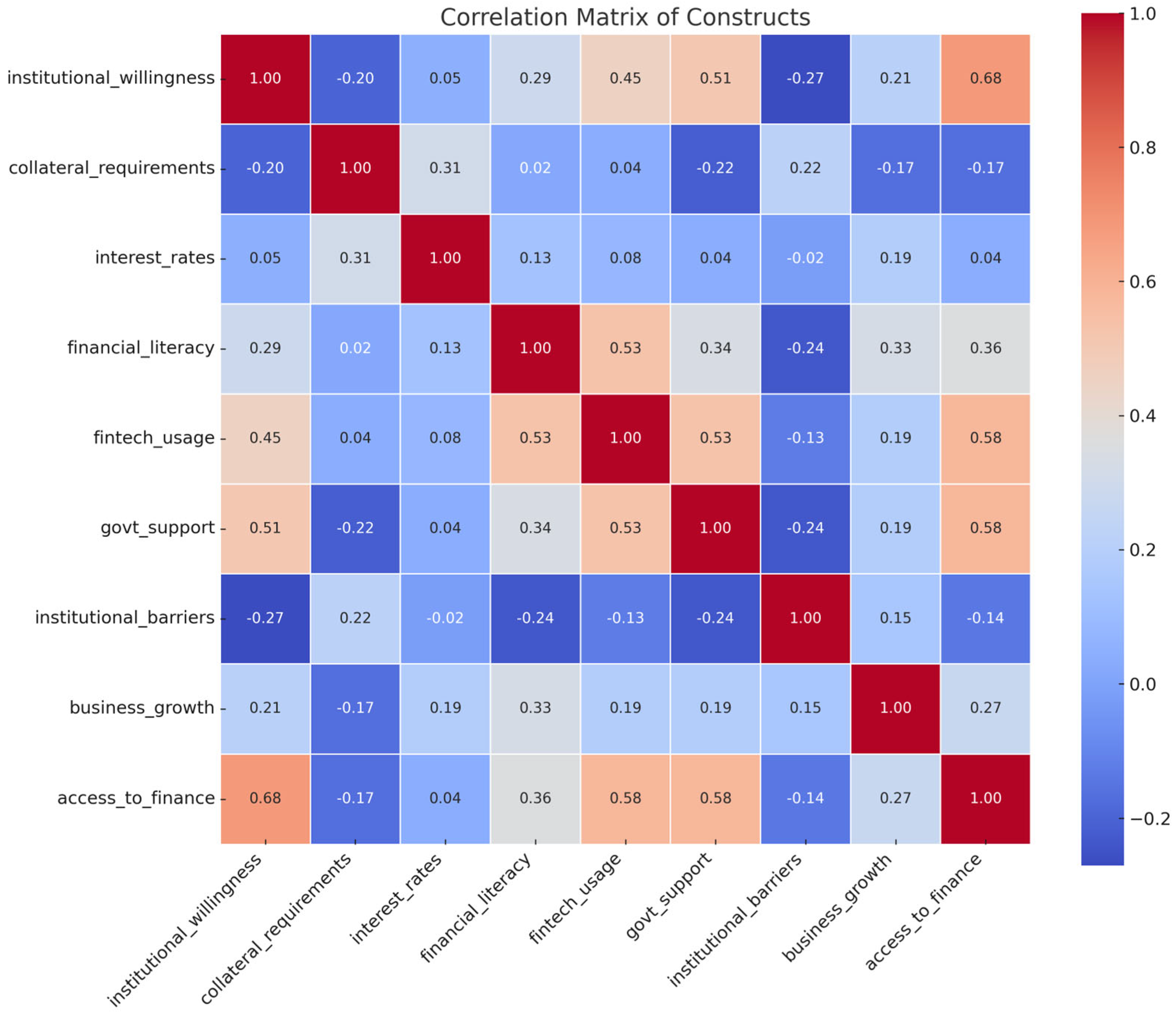

5.1.1. Correlation Analysis

- H1 examined the relationship between institutional willingness to lend (Q2.5) and ease of access to loans (Q2.1). A significant positive correlation (r = 0.52, p < 0.01) supported the hypothesis, indicating that SMEs perceiving lenders as willing reported better access to finance.

- H3 tested the association between high interest rates (Q4.1) and loan affordability (Q4.3). A strong negative correlation (r = −0.61, p < 0.001) confirmed that costly loans were linked to poorer accessibility.

5.1.2. Regression Analysis

- H2: Collateral requirements (Q3.1) negatively predicted loan access (β = −0.34, p = 0.002), controlling for firm size and sector.

- H4: Financial literacy (Q5.1–Q5.4) emerged as a significant positive predictor (β = 0.28, p = 0.013), explaining 19% of the variance in the access scores (R2 = 0.19).

5.1.3. Group Comparisons

- H5: SMEs using fintech platforms (Q6.3: “Yes”) reported significantly higher access to finance (M = 4.2, SD = 0.8) than non-users (M = 3.1, SD = 1.1; t [98] = 5.67, p < 0.001).

- H7: Perceived barriers (Q8.1–Q8.4) were stratified by loan approval status. Rejected applicants rated discriminatory practices (Q8.3) higher (M = 4.5) than approved ones (M = 2.9; p = 0.006).

5.1.4. Logistic Regression (Binary Outcomes)

- H6: Government support (Q7.1) increased the odds of securing loans (OR = 2.1, 95% CI [1.3, 3.4], p = 0.001).

5.1.5. Reliability and Validity

5.1.6. Strongest Relationships Between Constructs

- Institutional Willingness and Access to Finance: A strong positive correlation was observed between institutional willingness and access to finance (r = 0.683). The mean score for institutional willingness was 2.62, while access to finance had a mean of 2.21. This suggests that the perceived willingness of institutions to support SMEs plays a critical role in facilitating financial access.

- Government Support and Access to Finance: Government support also demonstrated a strong correlation with access to finance (r = 0.578), with a mean value of 2.37. This indicates that enhanced government backing, whether through policy frameworks or direct financial interventions, is associated with improved financial accessibility for SMEs.

- Fintech Usage and Access to Finance: The relationship between fintech usage and access to finance (r = 0.555) further supports the notion that digital financial services are becoming a vital channel for SME financing. Fintech usage had a relatively higher mean (2.81), suggesting growing engagement with financial technologies among respondents.

- Fintech Usage and Government Support: A notable correlation was found between fintech usage and government support (r = 0.531). This may indicate that government initiatives encouraging digital transformation are contributing to higher fintech adoption among SMEs.

- Financial Literacy and Fintech Usage: Finally, financial literacy and fintech usage were strongly correlated (r = 0.530). With financial literacy recording the highest mean (3.31), the data suggests that more financially literate respondents are more inclined to leverage fintech tools for business financing and operations.

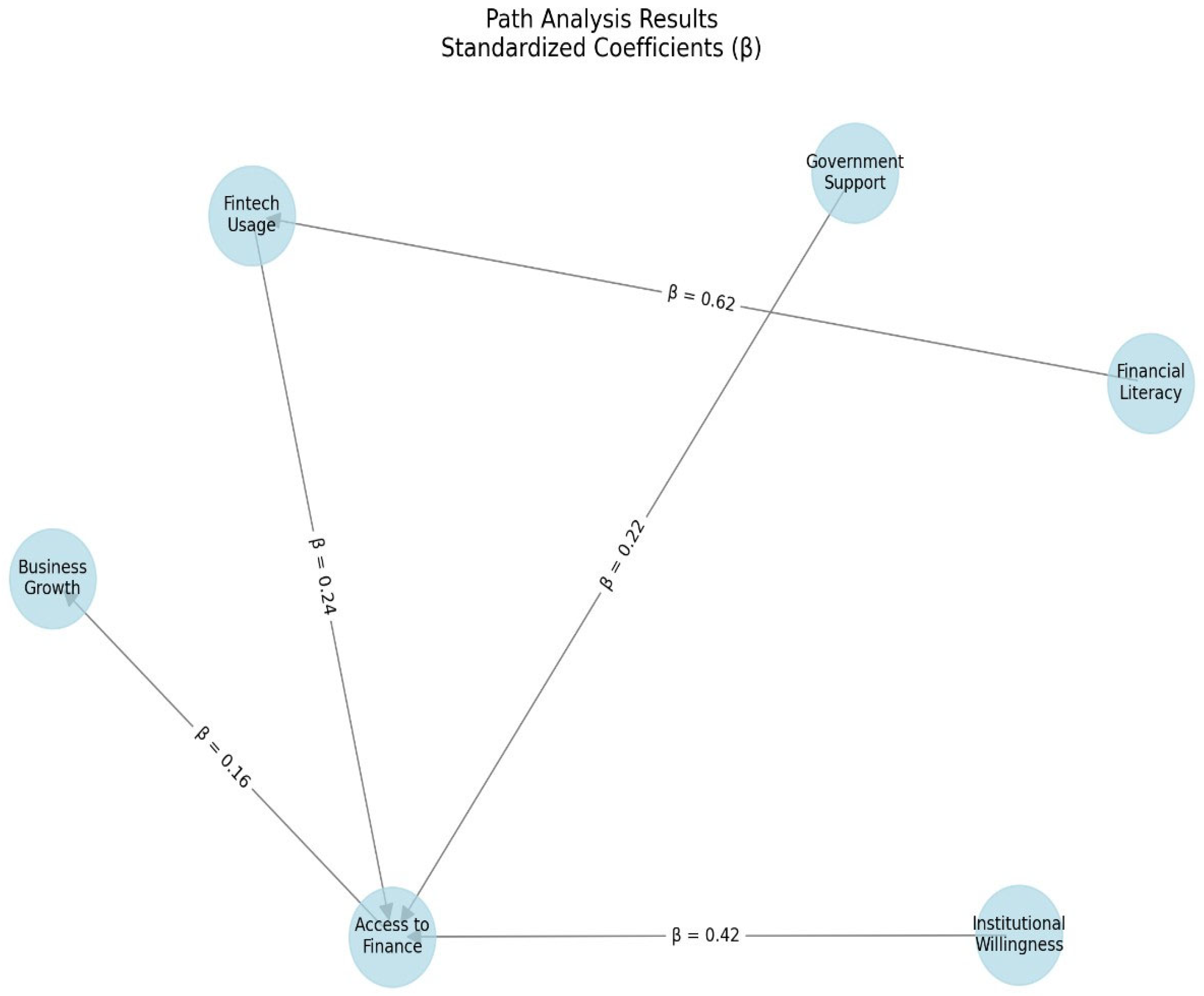

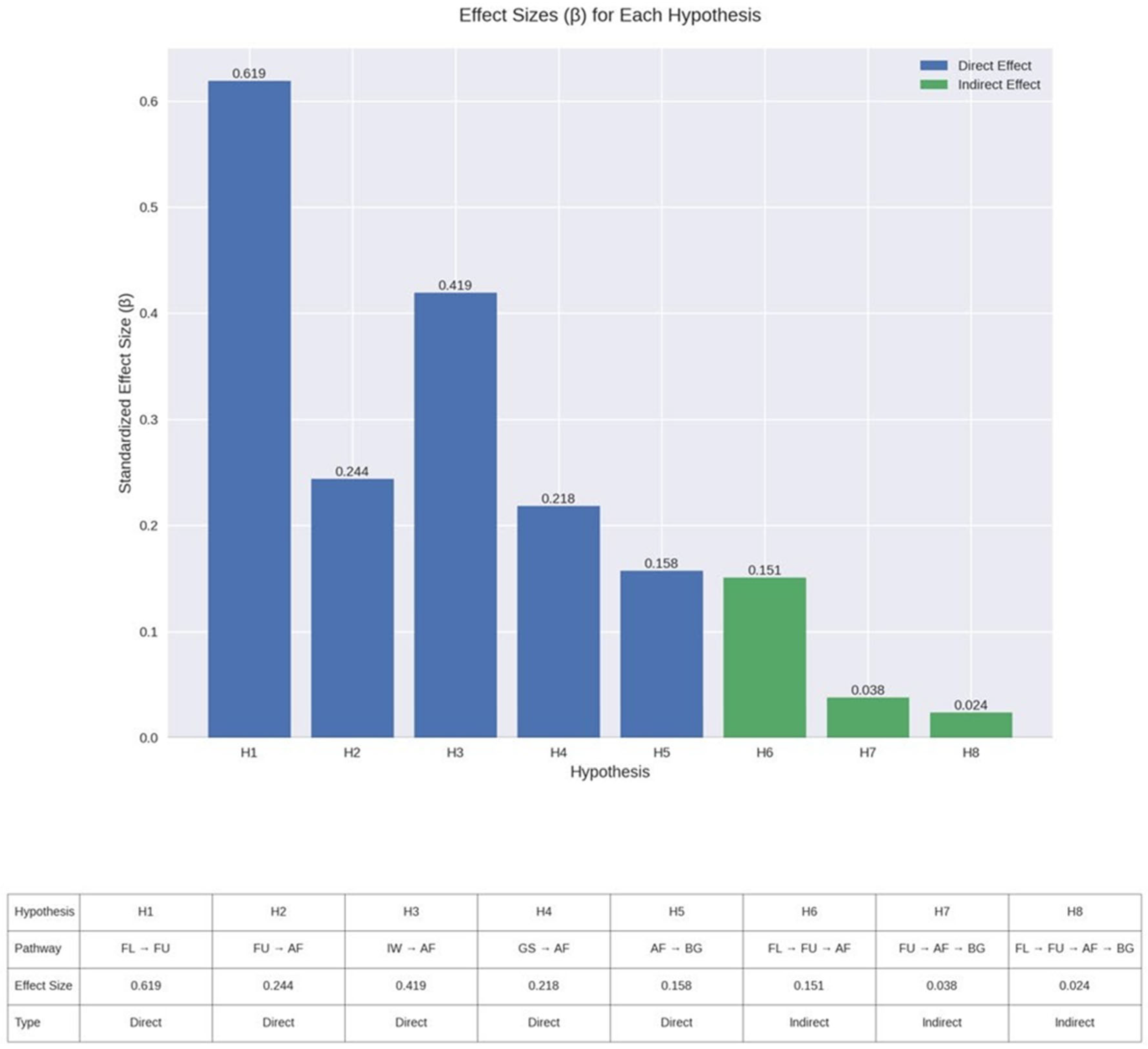

5.2. Path Analysis

- Strongest Direct Effects on Access to Finance

- ❖

- Institutional willingness emerged as the most influential predictor of access to finance (β = 0.42, p < 0.001), underscoring the critical role of supportive institutional frameworks.

- ❖

- Fintech usage followed with a significant positive effect (β = 0.24, p < 0.001), suggesting that digital financial solutions are pivotal in bridging financial access gaps.

- ❖

- Government support also had a notable direct effect (β = 0.22, p < 0.001), indicating that public-sector involvement remains a key enabler of financial accessibility.

- Financial Literacy and Fintech Usage

- ❖

- Financial literacy demonstrated a strong positive effect on fintech usage (β = 0.62, p < 0.001). This suggests that individuals with higher financial knowledge are significantly more likely to engage with fintech platforms and services. This pathway is particularly important for Sub-Saharan Africa’s digital finance policy development, as it highlights the need to embed financial education within national digital inclusion strategies. Strengthening financial literacy not only enhances the uptake of fintech solutions but also ensures that women entrepreneurs can safely and effectively navigate emerging digital financial ecosystems, reducing their dependence on informal or exploitative credit sources.

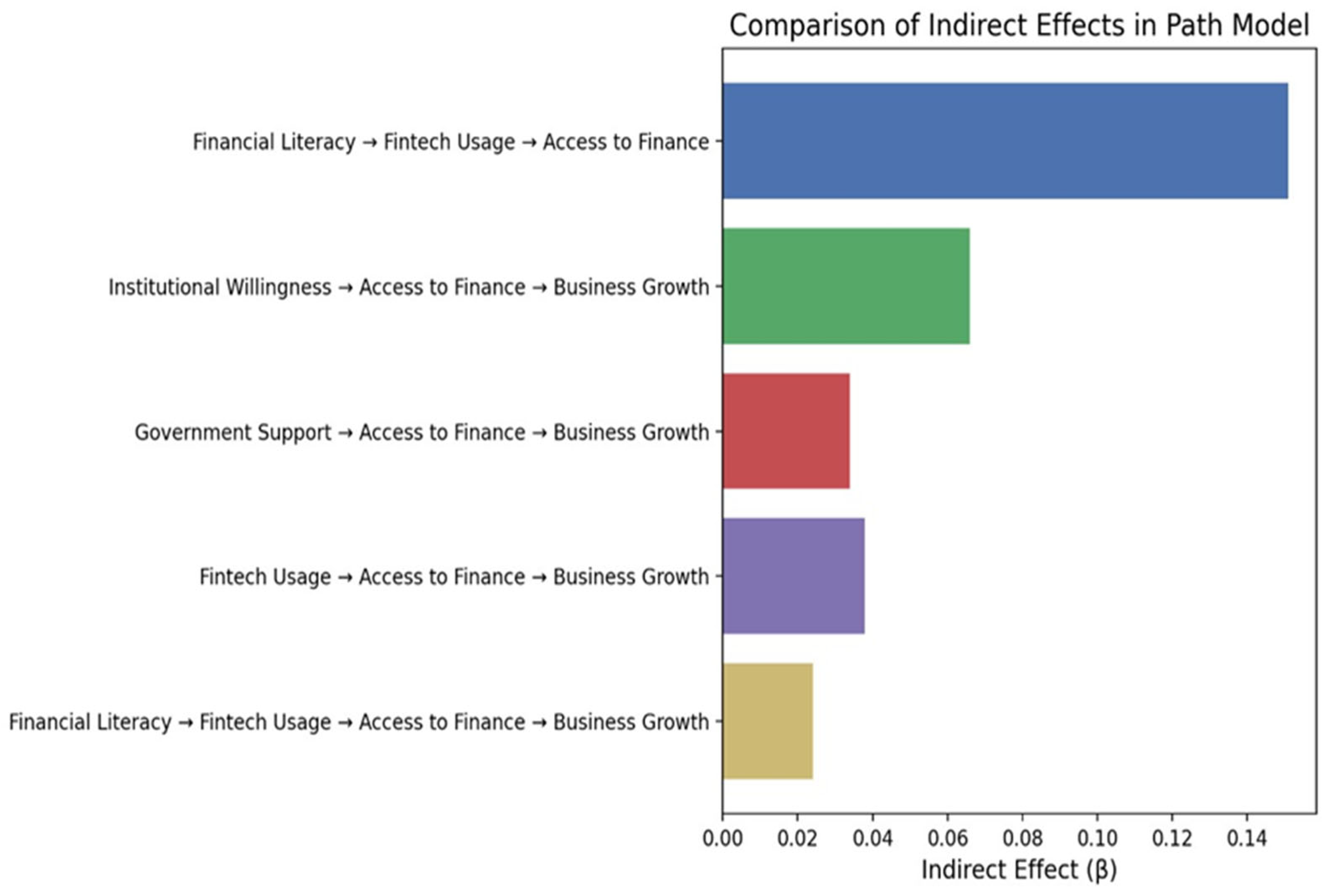

- Business Growth

- The strongest indirect path is Financial Literacy → Fintech Usage → Access to Finance (0.151), showing that financial literacy has a substantial indirect effect on access to finance through increased fintech usage.

- For business growth, institutional willingness has the strongest indirect effect (0.066), followed by fintech usage (0.038) and government support (0.034).

- Financial literacy has a smaller but significant three-path effect on business growth (0.024), demonstrating how improving financial literacy can ultimately contribute to business growth through the intermediary effects of fintech usage and access to finance.

- H1: Financial Literacy → Fintech Usage (β = 0.619)—strongly supported with the largest direct effect;

- H2: Fintech Usage → Access to Finance (β = 0.244)—supported with moderate effect;

- H3: Institutional Willingness → Access to Finance (β = 0.419)—strongly supported with the second-largest direct effect;

- H4: Government Support → Access to Finance (β = 0.219)—supported with moderate effect;

- H5: Access to Finance → Business Growth (β = 0.158)—supported with moderate effect.

- H6: Financial Literacy → Access to Finance (β = 0.151)—supported through mediation via fintech usage;

- H7: Fintech Usage → Business Growth (β = 0.038)—supported through mediation via access to finance;

- H8: Financial Literacy → Business Growth (β = 0.024)—supported through sequential mediation.

- All eight hypotheses are supported, indicating a valid theoretical model;

- The strongest relationship is between financial literacy and fintech usage (H1);

- Institutional willingness has the second-strongest effect on access to finance (H3);

- The indirect effects (H6–H8) are smaller but still significant, showing important mediating relationships.

6. Discussion

6.1. Institutional Willingness as a Pivotal Driver

6.2. The Enabling Role of Fintech and Financial Literacy

6.3. Government Support and Business Growth

6.4. Recommendations

6.4.1. For Policymakers

6.4.2. For Financial Institutions

6.4.3. For Women-Led Businesses

6.5. Implications for Policy and Practice

6.6. Theoretical Contributions

6.7. Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Acheampong, G. (2018). Microfinance, gender and entrepreneurial behaviour of families in Ghana. Journal of Family Business Management, 8(1), 38–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adom, P. K. (2015). Asymmetric impacts of the determinants of energy intensity in Nigeria. Energy Economics, 49, 570–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Y. A., & Kar, B. (2019). Gender differences of entrepreneurial challenges in Ethiopia. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/341078109 (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Akintola, A. A., Oji-Okoro, I., & Itodo, I. A. (2020). Financial sector development and economic growth in Nigeria: An empirical re-examination. Economic and Financial Review, 58(3), 59–84. [Google Scholar]

- Amine, L., & Staub, K. (2009). Women entrepreneurs in sub-Saharan Africa: An institutional theory analysis from a social marketing point of view. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 21(2), 183–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryeetey, E. (2005). Informal finance for private sector development in Sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Microfinance, 7(1), 3. [Google Scholar]

- Aryeetey, E. (2008). From informal finance to formal finance in Sub-Saharan Africa: Lessons from linkage efforts. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/254264799 (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- Aterido, R., Beck, T., & Iacovone, L. (2013). Access to finance in Sub-Saharan Africa: Is there a gender gap? World Development, 47, 102–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyagari, M., Demirgüç-Kunt, A., & Maksimovic, V. (2014). Bribe payments and innovation in developing countries: Are innovating firms disproportionately affected? Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 49(1), 51–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, T., & Demirguc-Kunt, A. (2006). Small and medium-size enterprises: Access to finance as a growth constraint. Journal of Banking and Finance, 30(11), 2931–2943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, T., Demirgüç-Kunt, A., & Maksimovic, V. (2008). Financing patterns around the world: Are small firms different? Journal of Financial Economics, 89(3), 467–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brixiová, Z., Kangoye, T., & Tregenna, F. (2020). Enterprising women in Southern Africa: When does land ownership matter? Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 41(1), 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Central Bank of Nigeria. (2011). Revised microfinance policy, regulatory and supervisory framework for Nigeria. Central Bank of Nigeria. [Google Scholar]

- Chilongozi, M. N. (2022). Microfinance as a tool for socio-economic empowerment of rural women in Northern Malawi: A practical theological reflection. Available online: https://scholar.sun.ac.za (accessed on 18 October 2024).

- Coleman, S., & Robb, A. (2009). A comparison of new firm financing by gender: Evidence from the Kauffman Firm Survey data. Small Business Economics, 33(4), 397–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cossa, A. J., Madaleno, M., & Mota, J. (2018, September 20–21). Financial literacy importance for entrepreneurship: A literature survey. European Conference on Innovation and Entrepreneurship (pp. 909–916), Aveiro, Portugal. [Google Scholar]

- De Bruin, A., Brush, C. G., & Welter, F. (2006). Introduction to the special issue: Towards building cumulative knowledge on women’s entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 30(5), 585–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirgüç-Kunt, A., Klapper, L., Singer, D., Ansar, S., & Hess, J. (2022). The Global Findex Database 2021: Financial inclusion, digital payments, and resilience in the age of COVID-19. World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Demirgüç-Kunt, A., Pedraza, A., & Ruiz-Ortega, C. (2021). Banking sector performance during the COVID-19 crisis. Journal of Banking and Finance, 133, 106305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirgüç-Kunt, A., & Torre, I. (2022). Measuring human capital in middle income countries. Journal of Comparative Economics, 50(4), 1036–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Trade and Industry. (2015). Annual report 2014/15: Vote 36 (outputs on gender & women’s economic empowerment). Department of Trade and Industry. [Google Scholar]

- DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebewo, P. E., Schultz, C., & Mmako, M. M. (2025). Towards inclusive entrepreneurship: Addressing constraining and contributing factors for women entrepreneurs in South Africa. Administrative Sciences, 15(1), 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elam, A. B., Brush, C. G., Greene, P. G., Baumer, B., & Dean, M. (2019). Women’s entrepreneurship report 2018/2019. Available online: https://scholarworks.smith.edu/conway_research (accessed on 17 January 2025).

- European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. (2021). Strategy for the promotion of gender equality 2021–2025. European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. [Google Scholar]

- GSMA. (2022). The mobile gender gap report 2022. GSMA. [Google Scholar]

- Helmke, G., & Levitsky, S. (2006). Informal institutions and democracy: Lessons from Latin America (G. Helmke, & S. Levitsky, Eds.). JHU Press. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y., Li, P., Wang, J., & Li, K. (2022). Innovativeness and entrepreneurial performance of female entrepreneurs. Journal of Innovation and Knowledge, 7(4), 100257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imhonopi, D., & Ugochukwu, M. (2013). Leadership crisis and corruption in the Nigerian public sector: An albatross of national development. The African Symposium, 13(1), 78–87. [Google Scholar]

- International Finance Corporation. (2023). IFC annual report 2023: Year in review. International Finance Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- International Labour Organization. (2023). Creating a conducive environment for women’s entrepreneurship development: Taking stock of ILO efforts and looking ahead in a changing world of work (ILO-WED Programme Compendium). International Labour Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Irene, B. N., Murithi, W. K., Frank, R., & Mandawa-Bray, B. (2021). From empowerment to emancipation: Womens entrepreneurship cooking up a stir in South Africa. In Women’s entrepreneurship and culture (pp. 109–139). Edward Elgar Publishing; Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Irene, B. N., Onoshakpor, C., Lockyer, J., Chukwuma-Nwuba, K., & Ndeh, S. (2025). Now you see them, now you don’t: Will technological advancement erode the gains made by women entrepreneurship in Sub-Saharan Africa? Journal of International Entrepreneurship. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, D. (2009). Constraints and opportunities facing women entrepreneurs in developing countries: A relational perspective. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 24(4), 232–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabeer, N. (2005). Gender equality and women’s empowerment: A critical analysis of the third millennium development goal. Source: Gender and Development, 13(1), 13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Kabiru, A. A., Ilesanmi, I. O., & Ayodeji, D. A. (2022). Effect of financial reporting quality and ownership structure on performance of the non-financial listed companies in Nigeria. Multidisciplinary Journal of Management Sciences, 4(3), 95–113. [Google Scholar]

- Karakire, G. (2015). Business in the urban informal economy: Barriers to women’s entrepreneurship in Uganda. Journal of African Business, 16(3), 305–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klapper, L., & Love, I. (2011). The impact of the financial crisis on new firm registration. Economics Letters, 113(1), 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klapper, L., Lusardi, A., & Panos, G. A. (2013). Financial literacy and its consequences: Evidence from Russia during the financial crisis. Journal of Banking and Finance, 37(10), 3904–3923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kongolo, M. (2010). Job creation versus job shedding and the role of SMEs in economic development. African Journal of Business Management, 4(11), 2288–2295. [Google Scholar]

- Laila, N., Ismail, S., Mohd Hidzir, P., Ratnasari, R., & Alias, N. (2025). Impact of social trust, social networks, and financial knowledge on financial well-being of micro-entrepreneurs in Malaysia and Indonesia. Cogent Business & Management, 12(1), 2460614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langevang, T., Gough, K. V., Yankson, P. W. K., Owusu, G., & Osei, R. (2015). Bounded entrepreneurial vitality: The mixed embeddedness of female entrepreneurship. Economic Geography, 91(4), 449–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I., & Shin, Y. J. (2018). Fintech: Ecosystem, business models, investment decisions, and challenges. Business Horizons, 61(1), 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2013). The economic importance of financial literacy: Theory and evidence. Available online: http://www.nber.org/papers/w18952 (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Meyer, J. W., & Rowan, B. (1977). Institutionalized organizations: Formal structure as myth and ceremony. American Journal of Sociology, 83(2), 340–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezgebo, G. K., Ymesel, T., & Tegegne, G. (2017). Do micro and small business enterprises economically empower women in developing countries? Evidences from Mekelle city, Tigray, Ethiopia. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 30(5), 767–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J. D. (1998). The measurement of civic scientific literacy. Public Understanding of Science, 7(3), 203–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngono, J. (2021). Financing women’s entrepreneurship in Sub-Saharan Africa: Bank, microfinance and mobile money. Labor History, 62(1), 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D. D., Nguyen, T. D., Nguyen, T. D., & Nguyen, H. V. (2021). Impacts of perceived security and knowledge on continuous intention to use mobile fintech payment services: An empirical study in Vietnam. Journal of Asian Finance, 8(8), 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2021). Education at a glance 2021. OECD. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2022). OECD economic outlook (Vol. 2022). OECD. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2023). 2023 OECD OURdata index open, useful and re-usable data index OECD public governance policy papers. OECD. [Google Scholar]

- Ogundana, O., Simba, A., Dana, L., & Liguori, E. (2021). Women entrepreneurship in developing economies: A gender-based growth model. Journal of Small Business Management, 59(1), 42–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olusegun, T. S., & Ado, N. (2023). Women financial inclusion and FinTech in Nigeria. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5019361 (accessed on 5 December 2024).

- Panda, S. (2018). Constraints faced by women entrepreneurs in developing countries: Review and ranking. Gender in Management, 33(4), 315–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattnaik, I., & Lahiri-Dutt, K. (2024). Feminization of hunger in climate change: Linking rural women’s health and wellbeing in India. Climate and Development, 16(7), 613–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, S., Elangovan, G., & Gupta, A. (2025). Digital engagement in financial inclusion for bridging the gendered entrepreneurial financial gap: Evidence from India. Cogent Business and Management, 12(1), 2518492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulka, B. M., & Gawuna, M. S. (2022). Contributions of SMEs to employment, gross domestic product, economic growth and development. Jalingo Journal of Social and Management Sciences, 4(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Razavi, S. (1997). Fitting gender into development institutions. World Development, 25(7), 1111–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razavi, S., & Miller, C. (1995). From WID to GAD: Conceptual shifts in the women and development discourse. United Nations Research Institute for Social Development (UNRISD). [Google Scholar]

- Saviano, M., Nenci, L., & Caputo, F. (2017). The financial gap for women in the MENA region: A systemic perspective. Gender in Management, 32(3), 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J. (2014). A matter of record: Documentary sources in social research. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, W. R. (2005). Institutional Theory: Contributing to a Theoretical Research Program. In Great minds in management: The process of theory development (Vol. 37). University Press. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/265348080 (accessed on 18 October 2024).

- Tanggamani, V., Rahim, A., Bani, H., Ashikin Alias, N., Melaka, C., Alor Gajah, K., & Gajah, A. (2024). Elevating financial literacy among women entrepreneurs: Cognitive approach of strong financial knowledge, financial skills and financial responsibility. Information Management and Business Review, 16(1), 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, P., Ocasio, W., & Lounsbury, M. (2012). The institutional logics perspective: A new approach to culture, structure, and process. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi, S., & Rajeev, M. (2023). Gender-inclusive development through Fintech: Studying gender-based figital financial inclusion in a cross-country setting. Sustainability, 15(13), 10253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumba, N. J., Onodugo, V. A., Akpan, E. E., & Babarinde, G. F. (2022). Financial literacy and business performance among female micro-entrepreneurs. Investment Management and Financial Innovations, 19(1), 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Women. (2023). Breaking growth barriers for women impact entrepreneurs in Indonesia. UN Women. [Google Scholar]

- Verheul, I., Van Stel, A., & Thurik, R. (2006). Explaining female and male entrepreneurship at the country level. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 18(2), 151–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woldesenbet Beta, K., Mwila, N. K., & Ogunmokun, O. (2024). A review of and future research agenda on women entrepreneurship in Africa. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour and Research, 30(4), 1041–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. (2019). World development report 2019. World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. (2022). World bank enterprise surveys (WBES). World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, F., Zhang, Q., & Jiang, D. (2023). The impact of regional environmental regulations on digital transformation of energy companies: The moderating role of the top management team. Managerial and Decision Economics, 44(6), 3152–3165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zetzsche, D. A., Arner, D. W., & Buckley, R. P. (2020). Decentralized finance. Journal of Financial Regulation, 6(2), 172–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Hypothesis | Independent Variable (IV) | Dependent Variable (DV) |

|---|---|---|

| H1 | Institutional willingness (Q2.5) | Access to finance (Q2.1, Q2.3) |

| H2 | Collateral requirements (Q3.1, Q3.2) | Access to finance (Q2.1, Q2.3) |

| H3 | Interest rates/costs (Q4.1–Q4.3) | Access to finance (Q2.1, Q2.3) |

| H4 | Financial literacy (Q5.1–Q5.4) | Access to finance (Q2.1, Q2.3) |

| H5 | Fintech use (Q6.3, Q6.4) | Access to finance (Q2.1, Q2.3) |

| H6 | Government support (Q7.1–Q7.3) | Access to finance (Q2.1, Q2.3) |

| H7 | Barriers (Q8.1–Q8.4) | Access to finance (Q2.1, Q2.3) |

| H8 | Access to finance (Q2.1, Q2.3) | Future growth (Q9.1) |

| Latent Variable/op/Return Variable | Estimate | Std. Err | z-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Access to finance ~ Institutional willingness | 0.419345899 | 0.051254224 | 8.181684635 | 2.22045 × 10−16 |

| Access to finance ~ Govt. support | 0.218484495 | 0.057813987 | 3.779094046 | 0.0001574 |

| Access to finance ~ Fintech usage | 0.24389267 | 0.052572251 | 4.639190148 | 3.4977 × 10−6 |

| Fintech usage ~ Financial literacy | 0.618707287 | 0.073956131 | 8.365868807 | 0 |

| Business growth ~ Access to finance | 0.157619386 | 0.044797867 | 3.518457411 | 0.000434063 |

| Access to finance ~ Access to finance | 0.361444816 | 0.03842115 | 9.407443861 | 0 |

| Fintech usage ~ Fintech usage | 0.550371088 | 0.058503787 | 9.407443861 | 0 |

| Business growth ~ Business growth | 0.271822361 | 0.028894391 | 9.407443861 | 0 |

| Hypothesis | Pathway | Effect Size (β) | p-Value | Supported? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Financial Literacy → Fintech Usage | 0.6187 | <0.001 | Supported |

| H2 | Fintech Usage → Access to Finance | 0.2439 | <0.001 | Supported |

| H3 | Institutional Willingness → Access to Finance | 0.4193 | <0.001 | Supported |

| H4 | Government Support → Access to Finance | 0.2185 | <0.001 | Supported |

| H5 | Access to Finance → Business Growth | 0.1576 | <0.001 | Supported |

| H6 | Financial Literacy → Access to Finance (indirect via Fintech Usage) | 0.151 | Calculated | Supported (indirect) |

| H7 | Fintech Usage → Business Growth (indirect via Access to Finance) | 0.038 | Calculated | Supported (indirect) |

| H8 | Financial Literacy → Business Growth (indirect via Fintech Usage and Access to Finance) | 0.024 | Calculated | Supported (indirect) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Irene, B.; Ndlovu, E.; Felix-Faure, P.C.; Dlabatshana, Z.; Ogunmokun, O. The Role of Financial Institutions in Bridging the Financing Gap for Women Entrepreneurs in Sub-Saharan Africa. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 323. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15080323

Irene B, Ndlovu E, Felix-Faure PC, Dlabatshana Z, Ogunmokun O. The Role of Financial Institutions in Bridging the Financing Gap for Women Entrepreneurs in Sub-Saharan Africa. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(8):323. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15080323

Chicago/Turabian StyleIrene, Bridget, Elona Ndlovu, Palesa Charlotte Felix-Faure, Zikhona Dlabatshana, and Olapeju Ogunmokun. 2025. "The Role of Financial Institutions in Bridging the Financing Gap for Women Entrepreneurs in Sub-Saharan Africa" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 8: 323. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15080323

APA StyleIrene, B., Ndlovu, E., Felix-Faure, P. C., Dlabatshana, Z., & Ogunmokun, O. (2025). The Role of Financial Institutions in Bridging the Financing Gap for Women Entrepreneurs in Sub-Saharan Africa. Administrative Sciences, 15(8), 323. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15080323