Abstract

The purpose of the current research study was to identify appropriate educators for teaching entrepreneurship at the university level and to explore the best teaching methods for developing entrepreneurial knowledge and skills among students. The study aims to address two key questions in entrepreneurship education: (1) Who should teach entrepreneurship in universities? and (2) What methods are effective in teaching entrepreneurship in universities? The study was conducted using an interpretative phenomenological qualitative research approach. Data were collected from a purposive sample of eight (8) entrepreneurship educators from a South African university. Data collection spanned three months, from November 2024 to January 2025. The key findings of the study suggest that entrepreneurship should be taught by academics with practical experience, academics with at least a Master’s degree, entrepreneurs invited as guest lecturers, incubator professionals, and technology professionals. Additionally, the research revealed teaching methods that can be used to effectively teach entrepreneurship in universities: Universities need to prioritise hiring and training entrepreneurship educators with both academic and real-world experience and facilitate collaborations with incubators and real-world entrepreneurs. Teaching methods need to incorporate experiential learning methods such as startup simulations, case studies, and partnerships with innovation hubs. The study offers valuable insights into who should teach entrepreneurship and how it should be taught, emphasising the need for a multidisciplinary approach and practical orientation to develop entrepreneurial capabilities and mindsets among students.

1. Introduction

This research seeks to contribute to the entrepreneurship discourse on who should teach entrepreneurship in universities and what teaching strategies are the best to deliver it. Earlier research by Amadi-Echendu et al. (2016) showed that alumni of entrepreneurship studies were unable to apply the theoretical knowledge gained from their training, and a high percentage indicated a need for practical knowledge on how to start a business. Universities often face challenges in identifying competent entrepreneurship educators and implementing effective teaching methods (Miço & Cungu, 2023). South African universities also face challenges in moving beyond traditional teaching methods and adopting various alternative approaches that stimulate entrepreneurial education (EE) and develop students’ skills (Ajani, 2024). A critical challenge to the success of entrepreneurship education has been identified as a shortage of qualified lecturers (Makwara et al., 2024). Furthermore, Makwara et al. (2024) assert that while academics are credited with developing critical thinking and analytical skills, critics worry about their lack of practical experience, which is essential for imparting real-world entrepreneurial skills.

There is still substantial confusion and debate in most Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) regarding what should be taught, how it should be taught, and who should do the teaching in entrepreneurship education (Musetsho & Lethoko, 2017). An important dimension of this debate is the acknowledgement of experiential learning theory, which advocates that learning through experience is a vital teaching approach to entrepreneurship. Experiential learning theory, as put forward by Kolb (2014), emphasises that meaningful learning takes place when students engage in concrete experiences, reflective observation, abstract conceptualisation, and active experimentation. Experiential learning theory underscores that entrepreneurship education needs to move from traditional lecture-based teaching methods to a more participatory and practice-based pedagogical approach that mirrors real-world entrepreneurship challenges (Bell & Bell, 2020; Tan et al., 2024). Although experiential learning theory is widely embraced, its application to practice remains inconsistent. Samwel Mwasalwiba (2010) asserts that lecturers, academicians, and trainers are the individuals responsible for delivering entrepreneurship but does not explicitly state the specific qualifications or backgrounds of those who must teach entrepreneurship. Furthermore, entrepreneurship educators often face a challenge in selecting teaching methods that align with their module objectives and the students’ learning environment, demographics, and socio-cultural backgrounds (Samwel Mwasalwiba, 2010). The challenge of implementing experiential learning theory in teaching entrepreneurship in Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) is further complicated by significant variation in course content across different HEIs, making the general effectiveness and appropriateness of entrepreneurship courses questionable (Iwu et al., 2024). Such inconsistencies stem from the lack of a common definition of entrepreneurship and the absence of a cohesive framework in determining who should teach entrepreneurship and how it should be taught (Makwara et al., 2024). This study thus questions whether entrepreneurship is sufficient for imparting entrepreneurial intention and entrepreneurial action, raising the issue of whether it is about how to teach entrepreneurship or who should teach it (teaching methods and instructors) or both, particularly through the lens of experiential learning.

Motta and Galina (2023) concluded that experiential learning serves as a valuable approach to entrepreneurial education, as it offers mechanisms to stimulate key aspects of entrepreneurship, such as motivating students and aiding them in developing entrepreneurial skills and competencies. Earlier research by Dhliwayo (2008) recommended integrating experiential learning into entrepreneurship education in South African HEIs. Despite the common acceptance of experiential learning theory in entrepreneurship education, there is still a lack of empirical research on the qualifications needed to be an effective entrepreneurship educator and the best methods to teach entrepreneurship in universities. This study will contribute to theoretical developments by expanding the literature on experiential learning theory in the area of entrepreneurship education. By utilising the research study results on who should teach entrepreneurship and the best methods to teach it, the research will apply experiential learning theory’s four-stage cycle: concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualisation, and active experimentation (Kolb, 1984). This will help in understanding the skills, attitudes, and pedagogical approaches that best support experiential learning in entrepreneurship. Thus, this study will contribute to extending entrepreneurial learning theory regarding who should teach and what the best methods are to teach entrepreneurship. Overall, the study will develop an evidence-based framework that will improve the effectiveness of experiential learning in entrepreneurship education when learning progresses through experiential learning theory’s four-stage process (Kolb, 1984): concepts, experience, reflection, and experimentation.

The objectives of entrepreneurship curricula play a crucial role in determining the appropriate teaching methods and, by implication, influence who should teach entrepreneurship (Sirelkhatim & Gangi, 2015). While Sirelkhatim and Gangi (2015) did not explicitly state that objectives determine who should teach, the descriptions of the methods for “teaching for” and “teaching through” entrepreneurship strongly imply that these objectives necessitate the involvement of competent entrepreneurs who combine academic and industry expertise to provide practical insights to students. In this regard, the current research study sought to explore the ideal entrepreneurship educator as well as the effective teaching methods for entrepreneurship in South African universities. The study supports the African Union Agenda 2063 goals, specifically goal number 2, well-educated citizens and skills revolution, and South Africa’s National Development Plan, goal number 7, education and training. The following research questions (RQs) guide the research study:

- RQ1: Who should teach entrepreneurship in universities?

- RQ2: What methods are effective in teaching entrepreneurship in universities?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Framework

Experiential learning theory provides the theoretical basis for the research study. Experiential learning is a valuable framework for understanding teaching methods and learning styles. Akella (2010) posits that experiential learning theory was propounded by Kolb in 1984. Kolb’s (1984) experiential learning theory explains how learning occurs through a four-stage cycle: concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualisation, and active experimentation. Experiential learning has recently been adopted as a method for entrepreneurial education due to its beneficial effects on entrepreneurial intention and the cultivation of entrepreneurial skills and competences (Dhliwayo, 2008; Motta & Galina, 2023). Experiential learning is often presented as a different method from traditional education, in which the educator serves as a subject matter expert who imparts information and knowledge to students. In traditional learning, the learner only reads about, hears about, or writes about realities but never comes into contact with them as a learning process (Keeton & Tate, 1978). In contrast, in experiential learning, the learner is directly in touch with the realities being studied. In line with that, in experiential learning, the facilitator believes that students can learn in their role, and the educator’s role is to remove obstacles and create conditions where learners can do so (Kolb, 2014). The student must continually choose the set of learning abilities that are used in a specific situation, where learning is conceived as a four-stage cycle, namely, experiencing, reflecting, thinking, and acting (McCarthy, 2016).

The structured process can help transform students’ experiences into actionable knowledge that is critical in teaching entrepreneurship. Thompson et al. (2009), cited in Duval-Couetil et al. (2016), created a model of entrepreneurship education and experiential learning, which showed a range of knowledge-building capabilities that are associated with various learning activities. Entrepreneurship education is considered more effective if it includes a strong experiential component, requiring students to intellectually and physically engage in the learning process and reflect on their experiences (Duval-Couetil et al., 2016). Many students learn about entrepreneurship through experiential activities embedded in courses or via extracurricular activities. Thompson et al.’s (2009) model illustrates the connection between different levels of experiential learning and their potential impact on entrepreneurial outcomes. Duval-Couetil et al. (2016) provided experiential learning activities in entrepreneurship education, which include the development of business plans, creation of startup companies by students, consultation with practising entrepreneurs, computer and behavioural simulations, interviews with entrepreneurs, field trips and the use of video, development of smartphone apps, internships with startups, investor pitches, and investor presentations. Prior research underscores the significance of experiential learning in entrepreneurship education (EE), stressing the need for active, practical involvement and real-world application (Kolb, 1984; Dhliwayo, 2008; Duval-Couetil et al., 2016; Motta & Galina, 2023).

It appears that educators with hands-on experience in entrepreneurship, like practitioner–entrepreneurs or entrepreneur–academics, improve learning outcomes by connecting theoretical knowledge with practical application. The research instrument development, data collection procedure, and data analysis were guided by experiential learning theory’s four-stage cycle: concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualisation, and active experimentation. Research has demonstrated that approaches such as simulations, startup projects, and mentorships produce superior entrepreneurial outcomes compared to conventional lectures. The current research questions are informed by these insights, with a focus on identifying the ideal entrepreneurship educator at the university level and the effective teaching methods for teaching entrepreneurship in universities. This study seeks to address the theoretical gap in examining the role of experiential learning theory in determining the ideal entrepreneurship educator and the best method to teach entrepreneurship at the university level. Utilising Kolb (1984)’s four-stage cycle—concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualisation, and active experimentation—the study will present a framework that will be used to determine who the ideal entrepreneurship educator is and which methods work best in teaching entrepreneurship.

2.2. Entrepreneurship Education

Entrepreneurship education (EE) plays a crucial role in equipping students with the skills and knowledge needed to identify opportunities and become successful entrepreneurs. According to Cascavilla et al. (2022), entrepreneurship education (EE) is a set of educational offerings aimed at preparing students to identify and act upon value-creating opportunities. EE aims to develop the skills and knowledge necessary for students to become successful entrepreneurs. According to Del Vecchio et al. (2021), EE is based on four main aspects: learning objectives and rationale (why); the contents (what); stakeholders and target students (who); and the learning process (how). In support of this, Samuel and Rahman (2018) state that EE centres on the design and implementation of entrepreneurship teaching and course programs based on various aspects, including entrepreneurship teaching methodologies that provide answers to questions about the purposes of learning (why), contents (what), methods (how), audiences and participants (for whom), and assessment outcomes. From the above discussion, answers to EE questions regarding why entrepreneurship should be learned, what must be taught, how it must be taught, and who must teach it are critical in enhancing the smooth implementation of EE in universities.

2.3. Who Should Teach Entrepreneurship?

The question “who should teach entrepreneurship?” is critical in the entrepreneurship education fraternity. In line with the experiential learning framework, ideal entrepreneurship educators need to guide learners through the four-stage process, that is, concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualisation, and active experimentation. Du Toit and Kempen (2020) emphasised the importance of teacher support through training and collaboration with others who have practical experience in entrepreneurship in the teaching of EE. They also called for collaboration between educators and entrepreneurial experts, which entails the need for educators to collaborate with experts from local businesses or experienced entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurship educators collaborate with seasoned entrepreneurs to help students by sharing real-life stories and mentoring them through hands-on activities, thereby gaining concrete entrepreneurship experience.

Waghid (2019) posited that teachers were not integrating entrepreneurship concepts into their teaching; thus they needed to be equipped with the skills and knowledge to teach entrepreneurship effectively. Entrepreneurship educators need training in experiential learning and business content to enable students to think independently and learn through experience (Miço & Cungu, 2023). In this regard, entrepreneurship educators need to challenge students to learn by doing and think outside the box (Miço & Cungu, 2023). Through learning by doing, students can practice active experimentation (Kolb, 2014). Active experimentation is pivotal in entrepreneurship education, as it can help turn entrepreneurial intentions into entrepreneurial actions.

Educators of entrepreneurship need to actively engage in both teaching entrepreneurship and research (Vecchiarini et al., 2024). This translates to the fact that research about entrepreneurship is a crucial aspect for entrepreneurship educators, as it can significantly enhance the educator’s entrepreneurial skills. According to Cualheta and Abbad (2021), entrepreneurship may be delivered by teachers with no specific training in entrepreneurship. Therefore, it is desirable for those teaching entrepreneurship to ensure the effective development of entrepreneurial competencies and the growth of small businesses. There is a need to train professors to address entrepreneurship in a more practical approach, and the community of entrepreneurship educators plays a crucial role in defining and enhancing the quality of teaching in the field (Cualheta & Abbad, 2021). While academics are essential for research and teaching theories, adjunct professors and practitioners with real-world consulting and practical experience are also vital (Zhou et al., 2024). Academic practitioners with real-world experience are more likely to effectively enhance students’ concrete entrepreneurship experience by guiding discussions, connecting experience to theory, and supporting and inspiring students to test their ideas in the real world. Recent research by Zhou et al. (2024) suggested that many academic staff members lack hands-on experience, such as structured training and startup expertise, indicating a need for instructors who possess practical entrepreneurial experience in addition to academic qualifications. This is a disadvantage for universities that aim to incorporate experiential learning theory into entrepreneurship education. Entrepreneurship cannot be effectively taught using the same methods as general management and business courses, emphasising the uniqueness of entrepreneurship, which requires more hands-on work (Tessema Gerba, 2012). Additionally, those who teach entrepreneurship need to have advanced degrees in relevant fields, such as a PhD, and possess more teaching and research experience, specifically in entrepreneurship. Also, entrepreneurship educators need specialised training in entrepreneurship beyond general business management and need to be equipped with teaching skills specific to entrepreneurship, moving beyond traditional lecture-based methods to more action-oriented approaches (Tessema Gerba, 2012).

Studies have shown that university entrepreneurship should be delivered by instructors who possess both academic credentials and hands-on entrepreneurial experience. To teach effectively, one needs specialised training, hands-on learning approaches, collaboration with business founders, and involvement in active research. By combining the expertise of both academics and practitioners, students can acquire a theoretical understanding, along with the practical skills vital for entrepreneurial success, and this is also central to experiential learning theory.

2.4. Entrepreneurship Teaching Methods

Effective strategies for teaching entrepreneurship at the university level encompass experiential and action-based learning, project-driven tasks, internships, case studies, guest lectures, collaborations with industry, and international exposure (Smith et al., 2022). In this study, it is critical, in line with experiential learning theory, to identify entrepreneurship pedagogies that can be effectively used by entrepreneurship educators to guide students through concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualisation, and active experimentation. Musetsho and Lethoko (2017) recommended the use of parallel-integrated teaching methods, such as project assignments, presentations, case studies, guest speakers, multiple contacts with local industries and entrepreneurs, internships, innovation hubs, and broader SMME (Small, Medium-, and Micro-Sized Enterprise) support networks in effectively teaching entrepreneurship. With the increasing globalisation of business, universities are offering global entrepreneurship programs that expose students to international markets and cultures. In this regard, Jardim et al. (2021) recommended that universities offer global entrepreneurship programs that expose students to international cultures and markets, including international internships, study-abroad internships, and collaborations with businesses and universities in other countries. Contributions by the above scholars show that experiential learning is critical to entrepreneurship education (Motta & Galina, 2023). Also, partnership with industry (Belitski & Heron, 2017), startup support services (Elenurm et al., 2019), and global entrepreneurship programs (Jardim et al., 2021). Syed et al. (2024) recommended the following teaching methodologies to be utilised in delivering entrepreneurship to university students in the UAE: experimental learning, action-based learning, individualised learning, catalyst approach, brainstorming sessions, hands-on experience, and project-based learning. In addition, Okello et al. (2024) state that, regarding teaching methods within the provision of entrepreneurship education, most Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) in East, West, and North Africa were using traditional methodologies, with common ones being formal lectures, field trips, in-class group discussions, and project-based learning. Furthermore, Okello et al. (2024) indicated that most HEIs focused on teaching subsistence agripreneurship, which is characterised by income generation for one’s family, buying and selling on a small scale, and employing just a few other people. Their study identified a need for these HEIs to adopt more innovative 21st-century teaching methods, such as community partnerships, including guest speakers, farm or industrial attachment, industrial-linked problem-based learning, collaborative teaching, and cooperative learning in teaching entrepreneurship in agricultural programs (Okello et al., 2024). Esmi et al. (2015) suggested three broad teaching–learning methods of entrepreneurship education: direct teaching–learning methods, interactive teaching–learning methods, and practical–operational teaching–learning methods. The discussion above shows that practical and experiential teaching methods like partnering with the industry, project-based learning, and case studies are pivotal to teaching entrepreneurship. There is no one entrepreneurship education method that can be used solely on its own, hence the need for collective adoption under a given circumstance (Samuel & Rahman, 2018; Nano et al., 2024; Rodrigues, 2023; Rosário & Raimundo, 2023; Pavel & Munteanu, 2024). This warrants further investigation into innovative teaching methods for engaging in EE in South African universities to enhance business development by graduates and also effectively support experiential learning theory in line with the four-stage process of effective learning, which comprises concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualisation, and active experimentation.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Approach and Sampling

The study was conducted using an interpretative phenomenological qualitative research approach. The study aimed to explore and understand how entrepreneurship educators experience the phenomenon at hand. Through this approach, the researchers gained deeper insights into the perceptions and interpretations of entrepreneurship educators regarding the roles and expertise of an ideal entrepreneurship educator. They also made sense of the lived experiences of the participants in relation to the phenomena under study. Additionally, utilising a descriptive approach, the researchers described the phenomenon in detail and captured the complexity and richness of the entrepreneurship educators’ lived experiences (Schindler, 2021). According to Creswell and Poth (2016), when using the interpretative phenomenological approach, it is essential to engage with people who have experienced that particular phenomenon. Therefore, university entrepreneurship educators, who design and deliver entrepreneurship modules, were considered the best participants for this study on the roles and expertise of an ideal entrepreneurship educator. Purposive sampling was used to select participants based on their knowledge of entrepreneurship education and their ability to identify the entrepreneurship modules offered at the university. Langston (2020) asserts that the interpretative phenomenological approach is often criticised for leading to the collection of vast amounts of data, which can be challenging for researchers to analyse effectively, resulting in poor identification of insights and emerging themes. In this study, a sample size of eight entrepreneurship educators was considered appropriate. The sampling criteria included educators involved in designing and delivering entrepreneurship modules, teaching the modules for more than three years, and a gender mix. Data saturation is a pivotal concept in qualitative research, as it ensures that data collection ceases once new insights, themes, and patterns emerge (Ahmed, 2025). Data saturation was determined by the researchers through the following methods: (1) purposive sampling was used to select entrepreneurship educators with lived and direct experiences with the phenomena, (2) using semi-structured interviews, educators were allowed to tell their stories in their own words, (3) data was analysed concurrently with data collection, and ATLAS.ti software was used to organise and monitor the emergence of themes. The semi-structured interviews were recorded, transcribed, and coded using ATLAS.ti version 24. Lastly, a saturation table was used to track theme development, and themes were documented when they recurred without variation. According to Ahmed (2025), data saturation is essential for attaining methodological rigour, as it boosts the credibility, trustworthiness, and completeness of the research findings.

3.2. Trustworthiness of Data

In order for the researchers to ensure the trustworthiness of the data, a comprehensive set of rigorously adhered-to research procedures was followed throughout the research process. Trustworthiness of the data was enhanced by selecting entrepreneurship educators who were knowledgeable and experienced in entrepreneurship education. Additionally, a semi-structured interview guide was crafted in alignment with the research questions and the theoretical framework of the study. Furthermore, the semi-structured interview guide underwent a comprehensive evaluation by experts in entrepreneurship, entrepreneurship education, and qualitative research studies to ensure that the interview questions were carefully designed to generate meaningful and rich data from the entrepreneurship educators concerning their perceived and lived experiences related to who should teach and what the best method for teaching entrepreneurship is.

Moreover, a pilot study was conducted on two entrepreneurship educators and one entrepreneurship official to test the efficacy of the semi-structured interview guide in generating the desired data and uncovering inconsistencies and ambiguities. The data collection period spanned three months, from November 2024 to January 2025, to allow adequate time for conducting research interviews, data transcription, and reflection. As data analysis was conducted concurrently with the data collection process, member checking was employed, where participants were asked to review the interview transcripts and thematic interpretations to provide feedback on whether the transcripts and interpretations accurately reflected their views. Peer debriefing was also conducted in the current study to ensure the trustworthiness of the data. The researchers engaged a colleague who was not directly involved in the current research to review the interview questions, data transcripts, and data interpretations.

3.3. Data Analysis

Qualitative data that was collected for this research was analysed using thematic analysis. According to Clarke and Braun (2013), thematic analysis is a flexible, interpretive qualitative method focused on identifying, analysing, and reporting patterns of meaning (themes) within qualitative data, with a strong emphasis on the researcher’s active role in constructing these themes. A theme is a coherent and meaningful pattern in the data relevant to the research questions (Braun & Clarke, 2014). The researchers in this study identified and reported themes that were related to who needs to teach entrepreneurship at the university level and what teaching method works best in entrepreneurship education. The researchers in this study followed a six-stage thematic analysis process, that is, becoming familiar with the data, generating initial codes, generating themes, reviewing potential themes, defining and naming themes, and producing the report (Braun & Clarke, 2014; Clarke & Braun, 2013; Terry et al., 2017). To begin with, the researchers acquainted themselves with the data by reviewing the transcripts several times and taking notes. The subsequent step entailed generating codes through the identification of key phrases, concepts, or ideas that mirrored participants’ perspectives on who ought to teach entrepreneurship and the methods for teaching it. Subsequently, these codes were organised into ideas that constituted themes pertinent to the research questions of the study. The researchers went back to the original data to check whether these themes are backed by evidence and accurately represent participants’ views. Finally, the researchers finalised the themes and consolidated the research article.

3.4. Ethical Considerations

The research study was approved by the University of the Western Cape, Research Ethics committee (HS24/7/15) before the data collection process began. The research participants were provided with information sheets outlining the purpose and importance of the research, their right to voluntarily participate, and their right to withdraw from the study at any time. The names of the participants were anonymised.

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Profile

The demographic profile of the study sample of eight entrepreneurship educators chosen from a South African university showed that half of the participants were PhD holders, while the other half were Master’s holders. All participants had more than three years of experience lecturing on entrepreneurship. Additionally, all participants had either lectured on entrepreneurship modules or were currently working as a Technology Transfer specialist (Participant 1) or Small Business Clinic coordinator (Participant 5). The demographic profile of the participants reflects an experienced and well-qualified group of entrepreneurship educators, suggesting that both practical experience and academic background influence effective teaching methods in entrepreneurship education and the suitability of educators in South African universities.

Table 1 provides information on the institution, designation and highest level of education of the participants.

Table 1.

Profile of entrepreneurship educators participating in the study.

4.2. Who Should Teach Entrepreneurship at University Level?

Table 2 below shows a summary of themes of participants’ responses regarding who should teach entrepreneurship at university level.

Table 2.

Summary of themes on who should teach entrepreneurship at university level.

4.2.1. Theme 1: Academics with Practical Experience

The nature of entrepreneurship is that it is a practice-driven domain dependent on real-world application, adaptability, and experimentation (Bender-Salazar, 2023; Huseynli & Bub, 2025). Entrepreneurship educators who possess practical experience can draw insights from their own businesses by illustrating both real-life case examples and theoretical concepts. This will enhance students’ understanding of how entrepreneurship theories evolve, thereby fostering critical thinking. The research participants highlighted that entrepreneurship in South African universities needs to be taught by academics who possess practical experience. The educators were of the view that an academic with practical experience in running an entrepreneurial venture would be in a position to balance between entrepreneurship theory and practice. This was shown by the following excerpts:

“I realised that it is important for entrepreneurship lecturers to have a practical background in order to use a practical approach in teaching the students, matching that with theory. This might include, for example, how to register a company, how to identify a product market, and how to overcome challenges involved in entrepreneurship”.(Participant 1; Quote 2)

And

“It is not only a Master’s qualification that is needed for one to teach entrepreneurship, but also practical experience. What I mean by that is there must be some sort of practical experience in starting or managing a business. So one can have a qualification in entrepreneurship or business management, but practical experience in running the business is also very important”.(Participant 2; Quote 2)

Also,

“It is important to practice what we teach. One cannot teach students to become entrepreneurs if they are not an entrepreneur themselves. As both a lecturer and an entrepreneur, I am able to apply the theory that I teach to run my business, and also show students how they can start their own businesses. This way, students will be motivated when they see that their lecturer not only teaches but also runs a business venture. Sometimes students come to me and say, ‘Ma’am, I have this business idea. I am motivated that you are also running a business. Can you please guide me on how to make the business idea work?”.(Participant 2; Quote 6)

And

“From my perspective, I think entrepreneurship lecturers must have been involved in entrepreneurship. Maybe they have run a small business or they run their own business for them to support the students to start their own businesses”.(Participant 5; Quote 1)

4.2.2. Theme 2: Master’s Degree

A key element in creating an ideal entrepreneurial ecosystem is to produce skilled and knowledgeable entrepreneurs through structured, recognised, and accredited education and entrepreneur training systems, as well as providing training for instructors (Looi & Maritz, 2021). Participants were of the view that educators who can teach entrepreneurship need to have a Master’s degree in Business Management, majoring in Entrepreneurship or even General Business Management. Participants 1, 2, and 3 gave the following comments:

“From my perspective, I think one needs to have a Master’s in management or a Master’s in management majoring in entrepreneurship to teach entrepreneurship education at the university level”.(Participant 1; Quote 1)

Also,

“One must have a minimum of a Master’s degree to teach entrepreneurship education at university level, and yes, a PhD is a bonus, but one actually needs to have at least a Master’s degree to teach entrepreneurship education at university level”.(Participant 2; Quote 1)

And

“The minimum qualification to teach entrepreneurship education at university level should be at least a Master’s degree, in my view, in a field related to business management.”(Participant 3; Quote 1)

4.2.3. Theme 3: Incorporation of Entrepreneurs as Guest Lecturers

Inviting guest speakers who are entrepreneurs is a suggested experiential learning approach in teaching entrepreneurship. Lecturers should invite entrepreneurs as guest speakers and allow students to interact with them, as this can generate interest among students and motivate them to start their own ventures after graduation (Mawonedzo et al., 2020). Participants were of the view that lecturers should incorporate the use of successful entrepreneurs as guest lecturers. This way, entrepreneurs can share their entrepreneurship journeys, the challenges they faced, and how they managed to overcome those challenges in the real world of business. This was evidenced by the following verbatim quotes:

“I always invite guest lecturers, such as the owner of Silulo Technologies, to come and share their real-life experiences with students. They talk about the challenges encountered in running a business and provide insights on managing entrepreneurial ventures, including marketing, human resources, finance, and information technology management”.(Participant 1; Quote 6)

And

“Guest lectures should also be given by entrepreneurs who are running their businesses. Students need to see actual role models in order to develop entrepreneurial competences and intentions. This motivates students and deepens their skill sets to start their own businesses”.(Participant 5; Quote 2)

4.2.4. Theme 4: Incubator Professionals

University incubators are identified as one of the most prominent mechanisms created to support entrepreneurial activity within universities (Ríos Yovera et al., 2025). Incubators are spaces that not only provide physical resources but also facilitate the creation of valuable connections between entrepreneurs, mentors, and investors. Incubators are a key component of university entrepreneurial ecosystems, alongside institutional infrastructure, collaborative networks, and support systems (Thottoli et al., 2025). Entrepreneurship educators at the case university emphasised the use of incubator professionals to teach entrepreneurship at the university level. As expressed by Participants 3 and 7,

“The business clinic can help our students get traction and move to the next level.”(Participant 3; Quote 4)

And

“Incubators are a very good platform for students, and their role is, for example, to help students enter the industry and engage experts in entrepreneurship education. I think it will benefit the students, and what is important is that entrepreneurship education shouldn’t just be a compulsory module in the qualification”.(Participant 7; Quote 5)

4.2.5. Theme 5: Collaboration with Technology Professionals

At the university level, working together with tech experts in entrepreneurial education promotes creativity, practical tech skills, and real-world problem-solving. It helps students stay competitive in a fast-changing digital economy by bridging the gap between theory and practice, improving curricular relevance, and preparing them to start tech-driven businesses. Participants highlighted the importance of entrepreneurship educators collaborating with technology professionals from the Technology Transfer Office to teach entrepreneurship education. The participants highlighted the following:

“Students also need to engage in programs initiated by the University Technology Transfer Office in order to develop their technology-related business plans into real-life businesses”.(Participant 1; Quote 8)

And

“Lecturers need to be aware of how to collaborate with entrepreneurship education entities like the Technology Transfer Office”.(Participant 3; Quote 5)

4.3. What Methods Are Effective in Teaching Entrepreneurship in Universities?

Table 3 provides a summary of themes on effective methods for teaching entrepreneurship in universities:

Table 3.

Summary of themes—best methods to teach entrepreneurship.

4.3.1. Theme 1: Business Plan Development

Business plan development was mentioned as one of the teaching methods used by entrepreneurship educators in delivering entrepreneurship in South African universities. Participants were of the view that the business plan would include all components, such as market research, marketing, finance, and operations management, which they could use in the future when they start their business ventures. Participant 1 detailed the following:

“The business plan provides students with all the components of entrepreneurship. Using the business plan, I can teach marketing, human resources, market research, financial management, operations management, among others. By the end of the module, students can integrate all the components and develop a business plan that they can use to seek funds to start their business ventures”.(Participant 1; Quote 15)

However, Participant 1 highlighted the need for universities to put business plans into practice and turn them into entrepreneurial action, meaning students should start their own business ventures. This was demonstrated by the following comment:

“There is also a need, maybe by the end of the module, to practice the business plan. The Department of Management and Entrepreneurship needs to provide the students with seed funds that will turn the business plans into real business ventures”.(Participant 1; Quote 26)

Participant 3 highlighted that business plan development was one of the outcomes of the entrepreneurship module. The participant further indicated that business plan development helps to achieve outcomes such as students starting their own businesses and becoming coaches to assist existing businesses.

“So the business plan is one of the outcomes, and they usually do it in groups. The other outcome that we are also targeting is that if the students do not go into entrepreneurship, they can go into business advising where they become coaches or assist businesses with different aspects of business management”.(Participant 3; Quote 8)

Furthermore, Participant 3 mentioned the importance of the complementary role of the Small Business Clinic, the incubator owned by the university, in linking students with investors who finance their business plans, enabling them to start practical business ventures. This was evidenced by the following excerpt:

“The Small Business Clinic can help students take their businesses to the next level. It provides students with the opportunity to pitch their business plans to organisations like Old Mutual, and the winners are rewarded with a prize. This collaboration serves as an incentive for students to start their businesses, turning their classroom-developed business plans into real-life ventures”.(Participant 3; Quote 9)

Participant 6 indicated that students come up with very good business plans after the module, but they do not know what to do after creating the business plans.

“Students came up with very good business plans after the entrepreneurship module. These business plans motivate them greatly to start their own business ventures, but they do not know how to take it to the next level, which is to start a practical business venture”.(Participant 6; Quote 1)

4.3.2. Theme 2: Business Registration

Registration of businesses gains additional trust from external parties, including customers and business partners, and this also affects market access and overall credibility (Maula et al., 2025). Furthermore, Maula et al. (2025) assert that the lack of understanding of administrative documents by entrepreneurial businesses limits their access to government support, such as training, financing, and other empowerment programs. In support of this, Lusha (2025) posits that businesses are more protected and customers have more trust because the businesses are officially registered (Lusha, 2025). Business registration opens up opportunities for businesses to expand their networks and access government programs. Participant 1 highlighted that they were helping some groups and individual students with business registration after developing the business plan.

“Four student groups and two individual students managed to register their businesses after developing their business plans in last year’s entrepreneurship module class”.(Participant 1; Quote 13)

4.3.3. Theme 3: Case Studies

The participants indicated that they were using case studies in teaching entrepreneurship. However, there were mixed feelings on the effectiveness of using case studies in teaching entrepreneurship at the university, as one educator highlighted the lack of use of local case studies.

“I use case studies in teaching my entrepreneurship class, but I usually face a challenge of a lack of local case studies. The case studies we use are mostly from books and may not apply in the South African context. The students thus struggle to apply the theoretical scenarios from the case studies to their own realities. We have a number of entrepreneurs who have been on campus for 20 years. For example, there is a lady in the area where we used to have big trees that were cut down. She offers an African-based menu, which is not offered anywhere else on campus. Using these types of case studies would be more beneficial to the students”.(Participant 4; Quote 8)

Participant 8 indicated that large entrepreneurship module class sizes were limiting lecturer–student interaction.

“Entrepreneurship classes are usually very large, with 200 or more students, which limits lecturer-student interaction and hinders effective class discussion, thereby limiting the impact of the case study teaching methodology on teaching entrepreneurship to students. Also, from my own perspective, students interpret case studies differently, leading to non-uniform learning outcomes”.(Participant 8; Quote 3)

4.3.4. Theme 4: Competitions

Competitions emerged as one of the teaching methods used by entrepreneurship educators to deliver entrepreneurship at the university. The university partnered with organisations like Old Mutual, with the assistance of the Small Business Clinic, to fund the competitions.

“So, we have a business plan competition that we have been running in the year 2024, which is an incentive for top business plans that come out of coursework. The best group was given R20,000 to start their own business by the Old Mutual group”.(Participant 3; Quote 7)

4.3.5. Theme 5: Real-World Engagement

The educators mentioned that students’ real-world engagement was one of the methods they were using to teach entrepreneurship. Real-world engagement is pivotal in enhancing students’ ability to apply theoretical entrepreneurship knowledge in practice (Borghi, 2024; Polydorou, 2025). Participant 2 emphasised the importance of giving students assignments that involve interviewing real-world entrepreneurs about their business management practices.

“So, what I do is visit small businesses to understand their business management practices, challenges, and opportunities. I will give you an example of what we recently did. I ask students to conduct interviews with entrepreneurs about their operations and the challenges they face, and then write a report on their findings.”(Participant 2; Quote 9)

Participant 5 highlighted that students develop business plans for existing entrepreneurial businesses.

“Students develop business plans where they need to improve an existing entrepreneurial business. So, the students had to go and work with a real-world business and help the small business owner improve the business plan for an existing small business. They will then present their business plans to the business owners, so we invite business owners who will also give input on the revised business plans. I do this to connect students to real-world business within the entrepreneurship module”.(Participant 5; Quote 7)

Participant 6 emphasised the need for university authorities to create businesses for students within the campus to help them turn their business plans into real entrepreneurial action.

“We already have the student center and the small business clinic. We need to create a small space for students where they pay, say R200 per space, to develop their business plans, such as selling sweets, food, or starting a hair salon, into real entrepreneurial action before they leave the university.”(Participant 6; Quote 2)

4.3.6. Theme 6: Guest Lectures by Real-World Entrepreneurs

Entrepreneurship educators mentioned the incorporation of entrepreneurs as guest lecturers as one of the methods that can lead to effective teaching of entrepreneurship at universities. This was shown by the following excerpts:

“I can teach entrepreneurship, but in some instances, I lack practical experience. In this regard, I engage seasoned entrepreneurs like Luvuyo Rani, the owner of Silulo Ulutho Technologies, to put into practice some of the theoretical aspects of entrepreneurship that I deliver to students”.(Participant 1; Quote 12)

Also,

“So every year, I ensure that I engage small business owners, especially those residing in areas where students come from, such as townships, where most of our students come from. Over the years, I have invited business owners to share their stories with the students and encourage them to start their own business ventures”.(Participant 2; Quote 11)

4.3.7. Theme 7: Integrating Technology

The design of technopreneurial education must effectively utilise these technological tools to shape entrepreneurial intentions (Maziriri et al., 2025). Furthermore, Maziriri et al. (2025) posit that universities and policymakers are encouraged to integrate technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI), Virtual Reality (VR), the metaverse, and live streaming into the entrepreneurship curriculum. In the current research, the participants emphasised the need for integration of technology into the entrepreneurship curriculum. Participant 7 echoed this notion in the following sentiments:

“Our students come from diverse backgrounds; we have others who come from rural areas and have come to university without being exposed to digital marketing platforms, such as social media platforms like TikTok, which are used to market business products and services. Therefore, digital marketing and social media marketing need to be integrated into the curriculum. We can include a topic in the module outline that teaches students how to create online businesses and how they can use the internet for business purposes.”(Participant 7; Quote 8)

Participant 8 also reiterated the importance of incorporating entrepreneurship education into the curriculum.

“Incorporating the use of social media platforms like Facebook and WhatsApp can help students start their businesses easily and reach out to customers effectively”.(Participant 8; Quote 9)

5. Discussion

This research study sought to explore entrepreneurship teaching practices in South African universities, specifically focusing on two aspects: “Who should teach entrepreneurship?” and “What teaching methods work best in teaching entrepreneurship at the university level?”

5.1. Who Should Teach Entrepreneurship?

The research findings revealed that entrepreneurship needs to be taught by academics with practical experience who can link real-world business practice with entrepreneurship theory learnt in class. The results resonate well with Din et al. (2020), who assert that in Malaysia, the teaching methods were less focused on theories and involved minimal lectures by lecturers, with their approach leaning more towards practical application. Also, Makwara et al. (2024) emphasised that entrepreneurship educators should embody entrepreneurial qualities, including practical experience and a hands-on approach, to effectively facilitate students’ transition from entrepreneurial intentions to actions. The research results also revealed that entrepreneurship educators need to hold at least a Master’s degree in Business or Entrepreneurship, thereby ensuring that they possess an educational foundation in both entrepreneurship practice and theory. The results are in line with Hägg and Kurczewska (2021), who assert that, as future entrepreneurs, students need to acquire solid knowledge in business and management, some legal knowledge, and entrepreneurial knowledge. The current research results also indicated the need to incorporate entrepreneurs as guest lecturers and to involve incubator professionals and technology professionals in teaching entrepreneurship. This resonates well with experiential learning theory. Hägg and Kurczewska (2021) posit that as an entrepreneurship educator, it is important to allow students freedom when engaging in the experience so that they feel that they have ownership of their learning.

Guest lectures by seasoned entrepreneurs enhance student engagement and also provide students with real-world success stories and challenges as they are narrated by entrepreneurs (Brahmankar et al., 2022). Also, Din et al. (2020) suggest that entrepreneurship educators in Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) may begin teaching entrepreneurship from various backgrounds, including as entrepreneurs, business educators, or researchers, with or without prior training in education. In this regard, entrepreneurship education not only needs to be taught by academics but must involve various stakeholders to strike a balance between theory and practice. The research findings on having entrepreneurship taught by academics with practical experience and having guest lectures by seasoned entrepreneurs support the experiential learning theory. Entrepreneurship educators with practical entrepreneurship experience embody the experiential learning theory, as they have lived through the concrete experience phase that can help students move through reflection, abstraction, and active experimentation. The real-world insights provided by lecturers and seasoned entrepreneurs allow students to engage with actual entrepreneurial challenges, not just case studies (Sibanda & Naidoo, 2023).

5.2. What Teaching Methods Work Best in Teaching Entrepreneurship at the University Level?

This study also identified several themes that offer valuable insights into the teaching methods that are used or can be used by entrepreneurship educators in South African universities. One prominent theme was business plan development, which involved the integration of key entrepreneurship elements, such as finance, human resources, marketing, information technology, and market research. This supports previous findings on the importance of using business plan development in teaching entrepreneurship (Dana et al., 2023; Dal Mas et al., 2023; Ferreras et al., 2017). Business plans are essential for conveying financial forecasts to meaningful stakeholders, like investors, banks, and public entities, making them a critical strategic business process for startups (Dana et al., 2023). The research findings support the experiential learning theory in that the students are not just learning about entrepreneurship, but rather they are engaging in it in a controlled academic environment. Business plan development enables the students to learn from concrete experience (engaging in real-world problem-solving) and also create something tangible (active experimentation) that the students can use to start their own businesses.

The current study identified case studies and competitions as key methods that can be used by entrepreneurship educators to effectively implement entrepreneurship education in universities. Active, practical methods, which would include competitions and case studies, offer benefits like stimulating attitudes, providing knowledge and skills, and allowing students to question, investigate, converse, and discuss with real-world entrepreneurs (Samwel Mwasalwiba, 2010; Ndou et al., 2018; Zotov et al., 2021). Building resilience, contextual relevance, critical thinking, entrepreneurial motivation, innovation and creativity, inspiration, and entrepreneurial career development are some of the effective contributions of using the case study method in entrepreneurship education (Musara, 2024). Using case studies in teaching entrepreneurship supports experiential learning theory, as students are exposed to the case study (concrete experience), analyse the case study (reflective observation), derive entrepreneurship principles (abstract conceptualisation), and apply lessons to the entrepreneurship cases analysed (active experimentation). Competitions also provide concrete, immersive experiences followed by reflection and adaptation, aligning with all the stages of experiential learning theory.

Another theme that emerged from the current study regarding entrepreneurship teaching methods was real-world engagement. The research findings revealed that through real-world engagement, students interact directly with existing businesses and entrepreneurs, conducting interviews to help entrepreneurs improve their businesses and enhance their business plans. This finding is consistent with previous studies that have shown that practice experts, such as entrepreneurs, work closely with student groups, assisting them with various aspects of business operations as needed (Secundo et al., 2023; Vohra et al., 2022). This mentorship role guides students in developing their own businesses. The theme of “integrating real-world entrepreneurs as guest lecturers” suggests that guest entrepreneurs enrich students’ learning by sharing their business experiences, complementing theory with practical insights, and inspiring students to confidently pursue their entrepreneurial ventures. In line with the experiential learning theory, students hear real-life stories of business success and challenges, which serve as lived examples of theory (Cunliffe & Easterby-Smith, 2017). These narratives motivate students to consider the relevance of entrepreneurial concepts in actual situations. Inspired by these experiences, students are more likely to apply what they have learned in their businesses. Integration of real-world entrepreneurs as guest lecturers helps students learn what they should learn by doing what entrepreneurs do, either in the classroom setting or in real life (Oliver & Oliver, 2022). The current study also aligns with Vohra et al. (2022), who emphasise the importance of students attending guest lectures by expert entrepreneurs and theory sessions on entrepreneurship. These interactions aim to provide students with knowledge and insights for their own ventures and learning. Students often find value in hearing entrepreneurs’ stories and relating them to the concept of effectuation and their own experiences (Nakajima & Sekiguchi, 2025). Both themes of real-world engagement and the incorporation of entrepreneurs as guest lecturers align with the core tenet of experiential learning theory, which emphasises learning through experience and the assimilation of new information and experiences (Kolb, 2014; Maziriri et al., 2022, 2025). Tiberius and Weyland (2024) assert that in order to develop or improve students’ entrepreneurship skills and attitudes, educators need to consider experiential learning designs as the most suitable. Applying experiential learning theory to entrepreneurship education promotes active, hands-on engagement, enabling students to translate real-world experiences into valuable entrepreneurial knowledge.

Lastly, the current research indicated that the integration of tools such as artificial intelligence and social media platforms in the entrepreneurship curriculum prepares students for entrepreneurial opportunities in business markets. Online Business Simulation (OBS), Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs), and social networking applications (Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, YouTube) are among the various teaching and learning approaches used in entrepreneurship education (Din et al., 2020; Maziriri et al., 2025). Incorporation of technology into teaching entrepreneurship supports experiential learning theory in that it helps students interact with realistic simulations, such as running a virtual startup or utilising Customer Relationship Management in a startup firm (concrete experience). Additionally, students can launch real or simulated businesses online, test products, and receive real-time feedback (active experimentation). Technology makes experiential learning more dynamic and accessible by enhancing the immersion, realism, and interaction of learning events.

6. Implications of the Study

6.1. Theoretical Implications

This study has various theoretical implications. It is evident that the findings of this research study underscore the importance of having academics with practical experience as ideal entrepreneurship educators and incorporating seasoned entrepreneurs as guest entrepreneurship lecturers. Also, exposing students to real-world experience is congruent with experiential learning theory. Real-world experience enhances concrete learning as university students take part in simulations, internships, and live entrepreneurial projects, providing them with firsthand experience of the challenges associated with starting their own businesses. Furthermore, guest lectures by real-world entrepreneurs help students to reflect (reflective observations) on their own experiences. By contrasting their own experiences with the narratives, setbacks, and wisdom of veteran entrepreneurs, students engage in reflection that fosters deeper analysis and comprehension. Also, academics with practical experience are key in enhancing the formation of entrepreneurship theories and concepts (abstract conceptualisation). Academics with practical experience are pivotal in helping students to link their insights to academic theories and frameworks, thereby creating organised entrepreneurial knowledge. Lastly, utilising real-world engagement reinforces testing of ideas in new situations (active experimentation). University students can refine their strategies and entrepreneurial thinking by applying learned concepts to new ventures or problem-solving scenarios. In this regard, the research findings are congruent with experiential learning theory, a theoretical best practice for teaching entrepreneurship and developing student entrepreneurs.

6.2. Practical Implications

This study also has practical implications for South African universities seeking to improve entrepreneurship education. Firstly, for universities to provide students with practical experience, curricula should incorporate real-world engagement opportunities like internships, incubator programs, and community-based projects. Additionally, when seasoned entrepreneurs give guest lectures, students can be introduced to genuine difficulties and triumphs, which can cultivate motivation and real-world understanding. Furthermore, by integrating case studies pertinent to the South African context, students can examine and address actual entrepreneurial challenges, thereby honing their critical thinking and decision-making abilities. Entrepreneurship competitions can foster innovation and the practical application of theoretical knowledge by offering students platforms to present and experiment with business concepts. It would be beneficial for universities to explore collaborations with business professionals and entrepreneurs to jointly create content and mentorship opportunities. In the end, incorporating these methods bolsters experiential learning and provides students with the skills, mindset, and connections necessary to succeed in the dynamic entrepreneurial environment of South Africa. Additionally, the incorporation of technology in entrepreneurship education allows for interactive simulations, virtual teamwork, and immediate feedback. This aligns with experiential learning by promoting active experimentation, reflective observation, and enhanced involvement in entrepreneurial problem-solving.

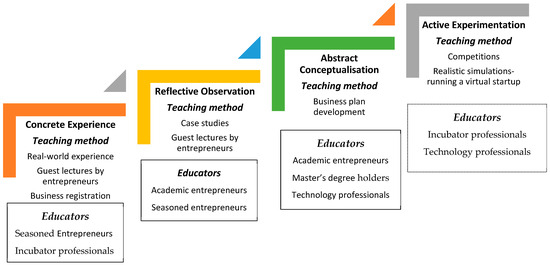

This study proposes an Experiential Learning–Entrepreneurship Education Framework that universities can use to identify the ideal entrepreneurship educator and the best method for teaching entrepreneurship. Based on Kolb’s (1984) experiential learning framework, which explains how learning occurs through a four-stage cycle—concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualisation, and active experimentation—the framework suggests entrepreneurship teaching methods and the ideal entrepreneurship educator at each stage. The framework presented in Figure 1 below is based on the research findings that emerged from the two main research questions that guided this study. The questions are as follows:

Figure 1.

Experiential Learning–Entrepreneurship Education Framework for universities. (Source: Created by the authors based on the research results).

- RQ1: Who should teach entrepreneurship in universities?

- RQ2: What methods are effective in teaching entrepreneurship in universities?

Concrete experience entails that learning begins with hands-on experience or activities that students actively participate in. Seasoned entrepreneurs can help students benefit from real-life entrepreneurship success stories and challenges that provide practical experience and provoke reflection. Through guest lectures with real-world entrepreneurs, students can engage in real-world entrepreneurship tasks and learn to navigate the administrative and legal issues of entrepreneurial ventures. Furthermore, incubator professionals’ experience in helping students’ startups aligns with hands-on learning.

Through case studies and guest lecturers by entrepreneurs, students can reflect on the experience, observing what happened and why it occurred. Academic entrepreneurs can guide the students to analyse real entrepreneurship cases for them to extract insights from theory. Success stories and challenges associated with entrepreneurial ventures from seasoned entrepreneurs can stimulate reflection and connect the theory the students learn in class to real-life entrepreneurship experiences.

Abstract conceptualisation enhances university students’ ability to form theories or conceptualise from reflections, connecting experiences to prior knowledge or new ideas. Academic entrepreneurs with Master’s degrees in business management can guide students in developing business plans to enhance abstract conceptualisation. Through business plan development, students can internalise business theories and apply them in developing actionable business plans. Additionally, technology professionals can enable the integration of digital tools and innovation frameworks into the entrepreneurship learning journey.

Active experimentation enhances university students’ ability to apply concepts in new situations, test ideas, and adjust entrepreneurship ideas based on outcomes. Technology professionals from University Technology Transfer Offices can help students learn technology-based tools for prototyping, analytics, and venture startups. Incubator professionals can guide students in pitching events and competitions that encourage testing of ideas. They can also mentor students through real-world entrepreneurship problem-solving and provide immediate, practical feedback on business ideas, prototypes, and business models. Additionally, incubator professionals can offer labs, workspaces, and tools for students to develop and test business ideas, as well as provide financial, legal, and marketing support. To further enhance active experimentation, incubators can connect students with investors, industry experts, and seasoned entrepreneurs for collaboration and feedback.

The Experiential Learning–Entrepreneurship Education Framework explained above can help universities to move away from passive lecture-based teaching and instead embrace experiential, student-centred learning, directly supporting and exemplifying experiential learning in entrepreneurship education.

7. Limitations and Suggestions for Further Research

The researchers acknowledge limitations, such as the study being conducted largely in a qualitative context, and data was collected from only one university setting based in Western Cape Province in South Africa. This limits generalisation of results across all universities in South Africa and developing countries at large. The data, however, was collected until data saturation, which determined the final sample of the study. The researchers believe that further research in the entrepreneurship education field can be conducted in similar or diverse contexts with relatively large sample sizes, possibly utilising quantitative research studies and comparative studies across different countries. Such studies can focus on the effectiveness of entrepreneurship teaching methods in enhancing entrepreneurial action among students. Also, future studies can focus on long-term evaluation of university incubator initiatives.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.M. and C.G.I.; Methodology, J.M.; Software, J.M.; Formal analysis, J.M.; Data curation, J.M.; writing—original draft preparation, J.M.; writing—review and editing, J.M. and C.G.I.; visualization, J.M.; supervision, C.G.I.; project administration, C.G.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was funded by the University of the Western Cape, Post-Doctoral Research Fellow-ship (2024).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical research principles were followed, including obtaining ethics clearance from the Humanities and Social Science Research Ethics Committee of the University of the Western Cape (protocol code HS24/7/15 and date 25 October 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Participants were informed, and consent was obtained from all of the subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this study’s findings are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ahmed, S. K. (2025). Sample size for saturation in qualitative research: Debates, definitions, and strategies. Journal of Medicine, Surgery, and Public Health, 5, 100171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajani, O. A. (2024). Entrepreneurship education in South Africa’s higher education institutions: In pursuit of promoting self-reliance in students. International Journal of Management, Knowledge and Learning, 13(1), 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akella, D. (2010). Learning together: Kolb’s experiential theory and its application. Journal of Management & Organization, 16(1), 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amadi-Echendu, A. P., Phillips, M., Chodokufa, K., & Visser, T. (2016). Entrepreneurial education in a tertiary context: A perspective of the University of South Africa. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 17(4), 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belitski, M., & Heron, K. (2017). Expanding entrepreneurship education ecosystems. Journal of Management Development, 36(2), 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, R., & Bell, H. (2020). Applying educational theory to develop a framework to support the delivery of experiential entrepreneurship education. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 27(6), 987–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender-Salazar, R. (2023). Design thinking as an effective method for problem-setting and need finding for entrepreneurial teams addressing wicked problems. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 12(1), 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghi, M. (2024). Embedding entrepreneurship and technology literacy in the student curriculum: A case study of a module for real estate students. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 62(3), 959–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahmankar, Y., Bedarkar, M., & Mishra, M. (2022). An entrepreneurial way of engaging student entrepreneurs at business school during pandemic. International Journal of Innovation Science, 14(3/4), 428–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2014). What can “thematic analysis” offer health and wellbeing researchers? International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 9(1), 26152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascavilla, I., Hahn, D., & Minola, T. (2022). How you teach matters! An exploratory study on the relationship between teaching models and learning outcomes in entrepreneurship education. Administrative Sciences, 12(1), 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, V., & Braun, V. (2013). Teaching thematic analysis: Overcoming challenges and developing strategies for effective learning. The Psychologist, 26(2), 120–123. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2016). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Sage publications. [Google Scholar]

- Cualheta, L. P., & Abbad, G. D. S. (2021). What does entrepreneurship education look like in Brazil? An analysis of undergraduate teaching plans. Education+ Training, 63(7/8), 1043–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunliffe, A. L., & Easterby-Smith, M. (2017). From reflection to practical reflexivity: Experiential learning as lived experience. In Organizing reflection (pp. 44–60). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Dal Mas, F., Massaro, M., Paoloni, P., & Kianto, A. (2023). Translating knowledge in new entrepreneurial ventures: The role of business plan development. VINE Journal of Information and Knowledge Management Systems, 53(6), 1159–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dana, L. P., Crocco, E., Culasso, F., & Giacosa, E. (2023). Business plan competitions and nascent entrepreneurs: A systematic literature review and research agenda. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 19(2), 863–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Vecchio, P., Secundo, G., Mele, G., & Passiante, G. (2021). Sustainable entrepreneurship education for circular economy: Emerging perspectives in Europe. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 27(8), 2096–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhliwayo, S. (2008). Experiential learning in entrepreneurship education: A prospective model for South African tertiary institutions. Education+ Training, 50(4), 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Din, W. M., Wahi, W., Zaki, W. M., & Hassan, R. (2020). Entrepreneurship education: Impact on knowledge and skills on university students in Malaysia. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 8(9), 4294–4302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Toit, A., & Kempen, E. L. (2020). Effectual structuring of entrepreneurship education: Guidelines for overcoming inadequacies in the South African school curriculum. Africa Education Review, 17(4), 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duval-Couetil, N., Shartrand, A., & Reed, T. (2016). The role of entrepreneurship program models and experiential activities on engineering student outcomes. Advances in Engineering Education, 5(1), n1. [Google Scholar]

- Elenurm, T., Tafel-Viia, K., Lassur, S., & Hansen, K. (2019). Opportunities of the entrepreneurship education for enhancing cooperation between start-up entrepreneurs and business angels. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 38(3), 379–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmi, K., Marzoughi, R., & Torkzadeh, J. (2015). Teaching learning methods of an entrepreneurship curriculum. Journal of Advances in Medical Education & Professionalism, 3(4), 172. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ferreras, R., Hernández-Lara, A. B., & Serradell-López, E. (2017). Entrepreneurship competences in business plans: A systematic literature review. Revista Internacional de Organizaciones, (18), 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hägg, G., & Kurczewska, A. (2021). Toward a learning philosophy based on experience in entrepreneurship education. Entrepreneurship Education and Pedagogy, 4(3), 316–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huseynli, M., & Bub, U. (2025). Enhancing learning in business development education through a method for engineering of digital innovation. Cogent Education, 12(1), 2444816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwu, C. G., Maziriri, E. T., Sibanda, L., & Makwara, T. (2024). Unpacking the entrepreneurship education conundrum: Lecturer competency, curriculum, and pedagogy. Administrative Sciences, 15(1), 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jardim, J., Bártolo, A., & Pinho, A. (2021). Towards a global entrepreneurial culture: A systematic review of the effectiveness of entrepreneurship education programs. Education Sciences, 11(8), 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeton, M. T., & Tate, P. J. (Eds.). (1978). The boom in experiential learning. In Learning by experience: What, why, how (pp. 1–8). JosseyBass. [Google Scholar]

- Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Kolb, D. A. (2014). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. FT press. [Google Scholar]

- Langston, C. (2020). Entrepreneurial educators: Vital enablers to support the education sector to reimagine and respond to the challenges of COVID-19. Entrepreneurship Education, 3(3), 311–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Looi, K. H., & Maritz, A. (2021). Government institutions, entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurship education programmes in Malaysia. Education+ Training, 63(2), 271–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusha, E. (2025). Empowering young entrepreneurs: Strategies for fostering innovation and entrepreneurship. Interdisciplinary Journal of Research and Development, 12(1), 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makwara, T., Iwu, C. G., Sibanda, L., & Maziriri, E. T. (2024). Shaping students’ entrepreneurial intentions into actions: South African lecturers’ views on teaching strategies and the ideal educator. Administrative Sciences, 14(12), 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maula, F., Setyawati, A., Rahma, A., Pratesa, D. P. M., & Mufidah, E. (2025). The role of business administration and entrepreneurship education, with government support, in advancing MSME efforts towards achieving the SDGs. Economics and Business Journal (ECBIS), 3(2), 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawonedzo, A., Tanga, M., Luggya, S., & Nsubuga, Y. (2020). Implementing strategies of entrepreneurship education in Zimbabwe. Education+ Training, 63(1), 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maziriri, E. T., Mabuyana, B., & Nyagadza, B. (2025). Navigating the technopreneurial odyssey: Determining how technopreneurial self-efficacy, technopreneurial education and technological optimism cultivate tech-driven entrepreneurial intentions. Management & Sustainability: An Arab Review, 4, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maziriri, E. T., Nyagadza, B., Maramura, T. C., & Mapuranga, M. (2022). “Like mom and dad”: Using narrative analysis to understand how couplepreneurs stimulate their kids’ entrepreneurial mindset. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 16(3), 784–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, M. (2016). Experiential learning theory: From theory to practice. Journal of Business & Economics Research (JBER), 14(3), 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]