Female-Led Rural Nanoenterprises in Business Research: A Systematic and Bibliometric Review of an Overlooked Entrepreneurial Category

Abstract

1. Introduction

Conceptual Delimitation of Nanoenterprises

- Self-employment or family-based labor (typically ≤2 people);

- Absence of legal registration or fiscal traceability;

- Low to zero capital investment;

- Localized and subsistence-oriented market strategies;

- Limited or no access to formal credit, technology, or training.

- RQ1: How has the concept of nanoenterprises evolved in scientific literature to date?

- RQ2: Which are the main characteristics and differences between nanoenterprises, microenterprises, and small businesses?

- RQ3: In which sectors have nanoenterprises been most developed?

- RQ4: Which challenges do women nanoentrepreneurs face and which strategies have proven successful for their inclusion in the business ecosystem?

- Lack of a commonly accepted definition: The concept of nanoenterprise remains poorly structured, hindering cross-study comparisons and limiting the design of inclusive policies for these ventures.

- Focus on basic needs: Unlike MSMEs (micro-, small, and medium enterprises), these economic units primarily operate under survival constraints, relying on familial networks and lacking full integration into the formal economic system.

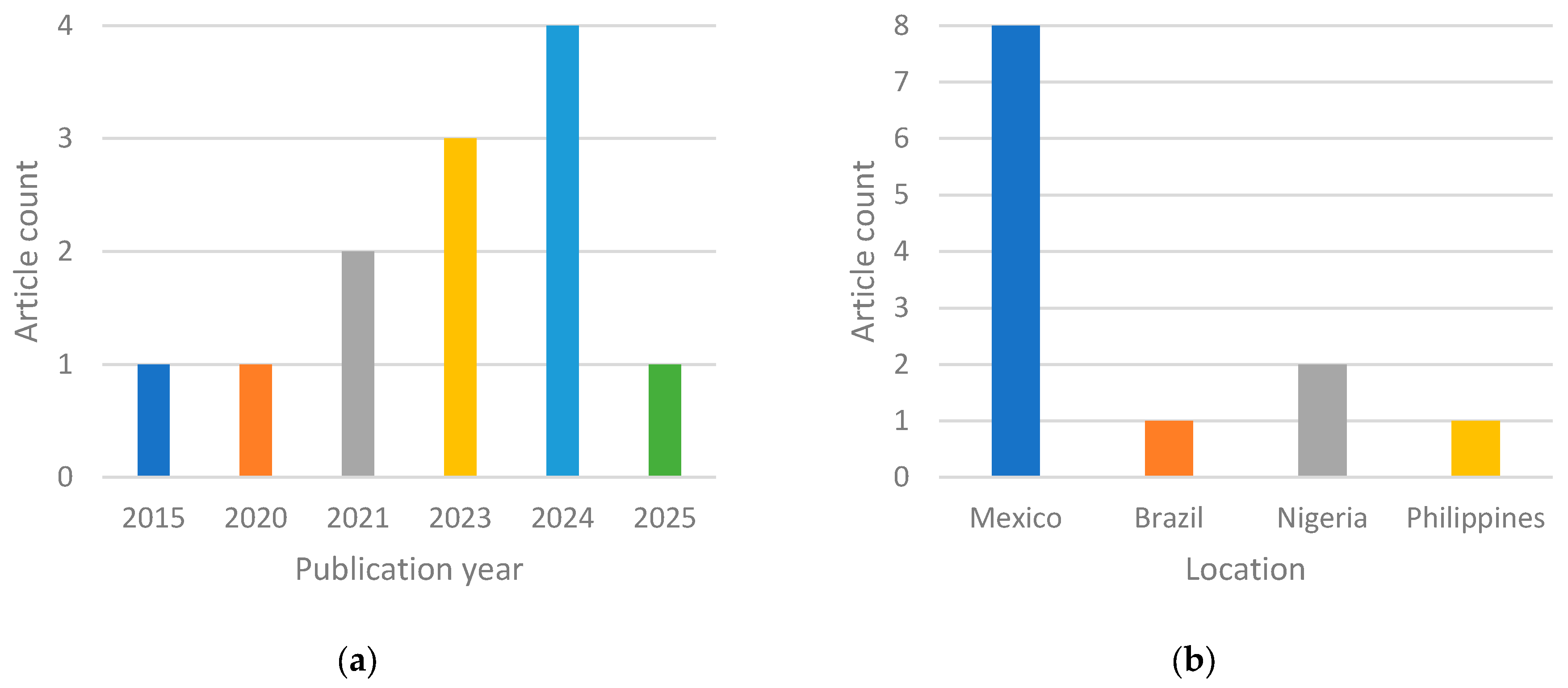

- Geographical concentration of studies: Research is heavily concentrated in countries such as Mexico, Nigeria, Philippines, and Brazil, while regions like Europe, and North America remain underrepresented in the available literature.

- Gender disparities: Women-led nanoenterprises reflect structural inequalities in access to financing, technologies, support networks, and training opportunities.

- Sectoral limitations: Although studies predominantly focus on informal trade and services, significant gaps exist in strategic sectors such as rural tourism, street vendors, informal domestic workers, and others.

- Under analyzed transformative potential: Nanoenterprises could drive empowerment, sustainability, and social cohesion, yet they remain overlooked in global economic development agendas.

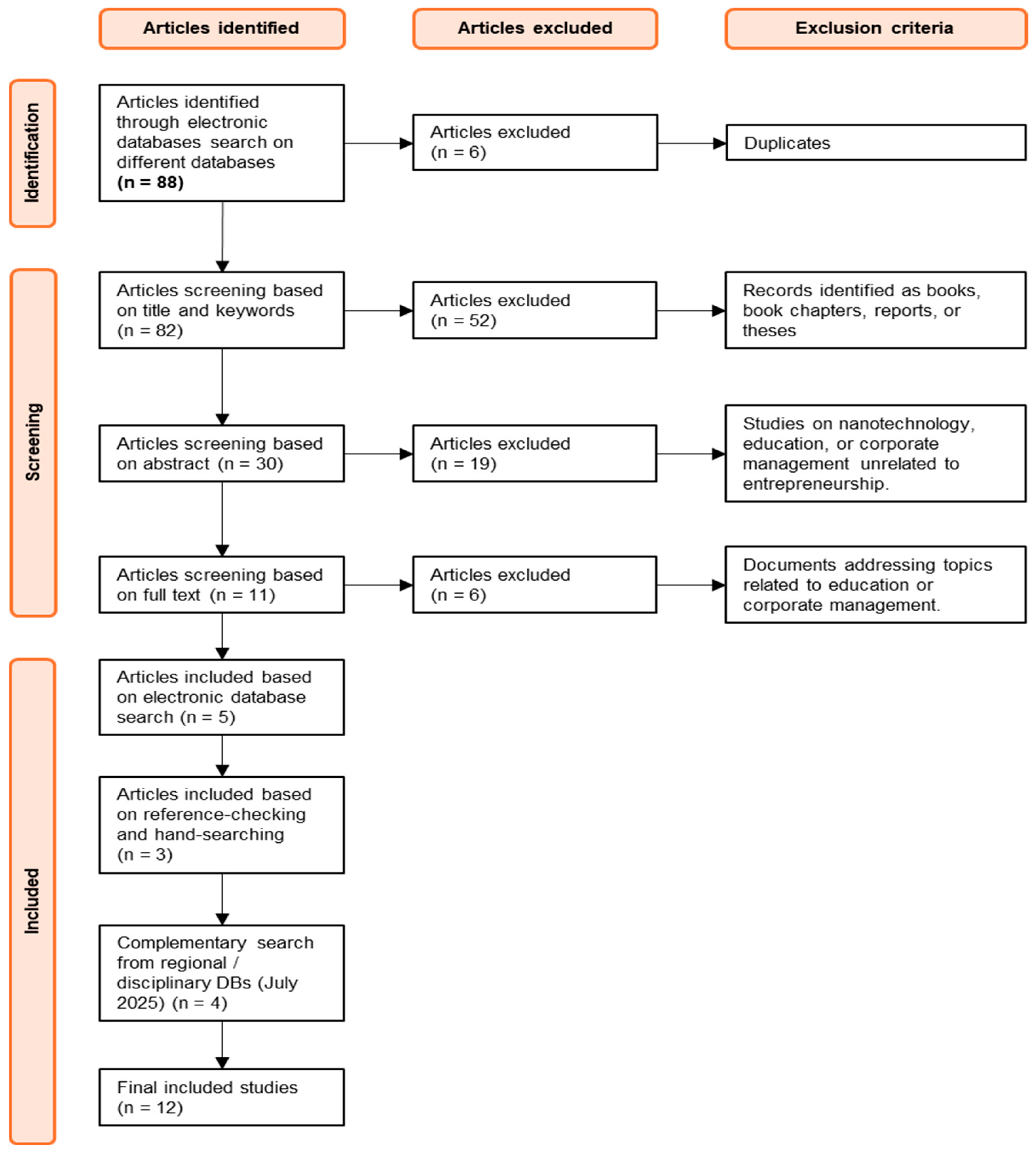

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- Peer-reviewed journal articles (no books, theses, or reports);

- Studies addressing nanoenterprises, nanoentrepreneurs, or nanoenterprises in any geographical context;

- Publications focusing on women entrepreneurs or rural entrepreneurship;

- Articles published in any language;

- Documents with verifiable DOI or reliable identifier.

- Publications about nanotechnology or any other use of the “nano” prefix unrelated to business;

- Studies without full-text availability;

- Non-peer-reviewed sources;

- Articles addressing education, public policy, technologies, or corporate management unrelated to entrepreneurship.

2.3. Article Selection Process

- Recent publications (2023–2025);

- Regional journals not captured by Google Scholar’s main algorithm;

- Multidisciplinary databases, including Latindex and Dialnet.

2.4. Complementary Literature

2.5. Data Extraction and Thematic Coding

- Title, year, and country of publication.

- Journal quality (indexing, impact).

- Keywords and thematic focus.

- Gender and sectoral lens.

- Citation counts

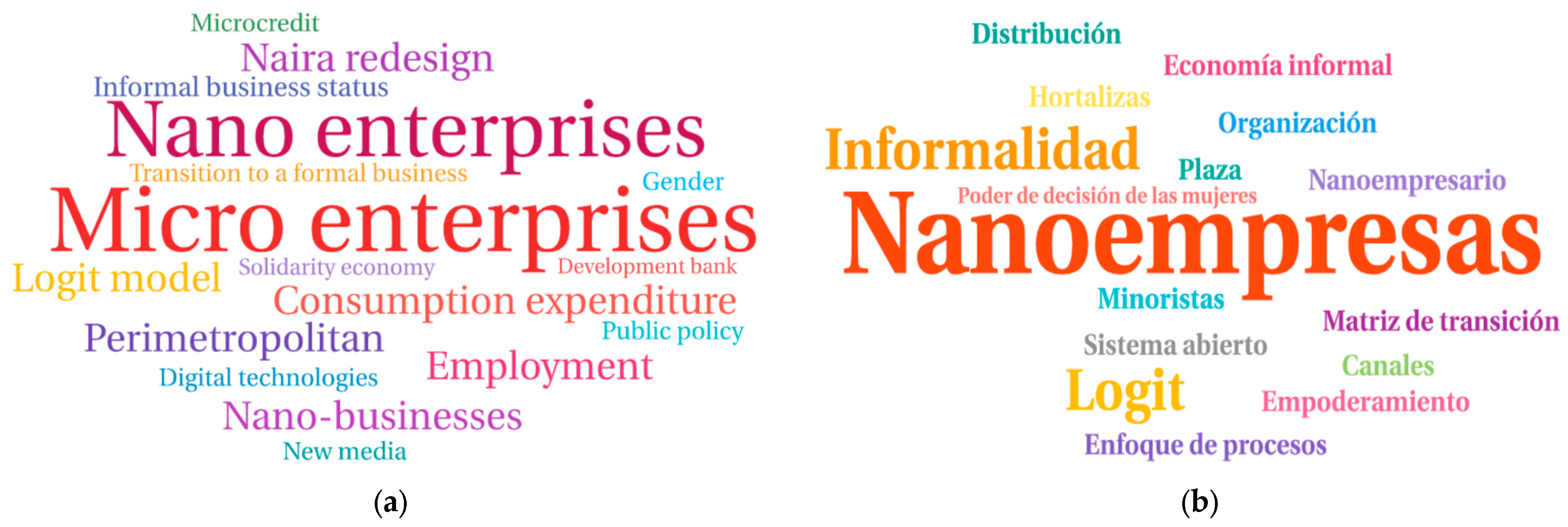

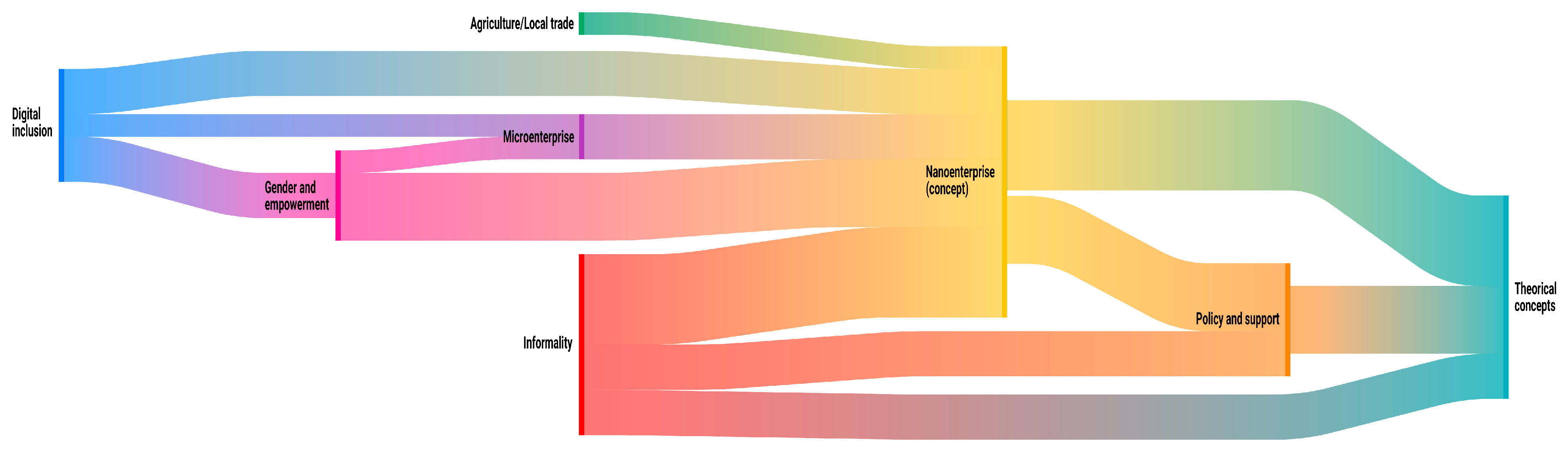

2.6. Bibliometric Analysis Strategy

- Word cloud visualizations for English and Spanish keywords.

- Keyword co-occurrence matrix categorized by thematic family.

- Keyword frequency graph by conceptual group.

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Analysis of Bibliometric Results

3.1.1. Publication Year Analysis and Geographical Distribution

3.1.2. Scientific Journal Analysis

3.1.3. Citation Analysis of Included Articles

3.2. Thematic Analysis of Systematic Review Results

3.2.1. Definitional and Conceptual Boundaries of Nanoenterprises

3.2.2. Sectoral and Geographic Patterns

3.2.3. Intersectional Challenges: Gender, Digital Access, and Territorial Exclusion

- Limited financial access, with exclusion from formal credit systems and microfinance programs (Alvarado Lagunas, 2021; Cunanan et al., 2025).

- Minimal participation in business support networks, exacerbating isolation (Ola-Akuma & Okocha, 2024; Mendoza Guerrero et al., 2024).

- Domestic responsibility overload, reducing time for enterprise growth (Gussi & Thé, 2020).

- Technical/digital skill gaps, hindering technological adoption (Rodríguez Medina et al., 2023; Canales-García et al., 2024).

- Market exclusion and regulatory invisibility, particularly among informal street vendors operating in urban margins (Valencia-Sandoval et al., 2023).

- Gendered perception of entrepreneurial capacity, where women’s informal businesses are often undervalued or not recognized as legitimate economic activity (Mendoza Guerrero et al., 2024).

4. Discussion

4.1. RQ1: How Has the Concept of Nanoenterprises Evolved in Scientific Literature to Date?

4.2. RQ2: Which Are the Main Characteristics and Differences Between Nanoenterprises, Microenterprises, and Small Businesses?

4.3. RQ3: In Which Sectors Have Nanoenterprises Been Most Developed?

4.4. RQ4: Which Challenges Do Women Nanoentrepreneurs Face and Which Strategies Have Proven Successful for Their Inclusion in the Business Ecosystem?

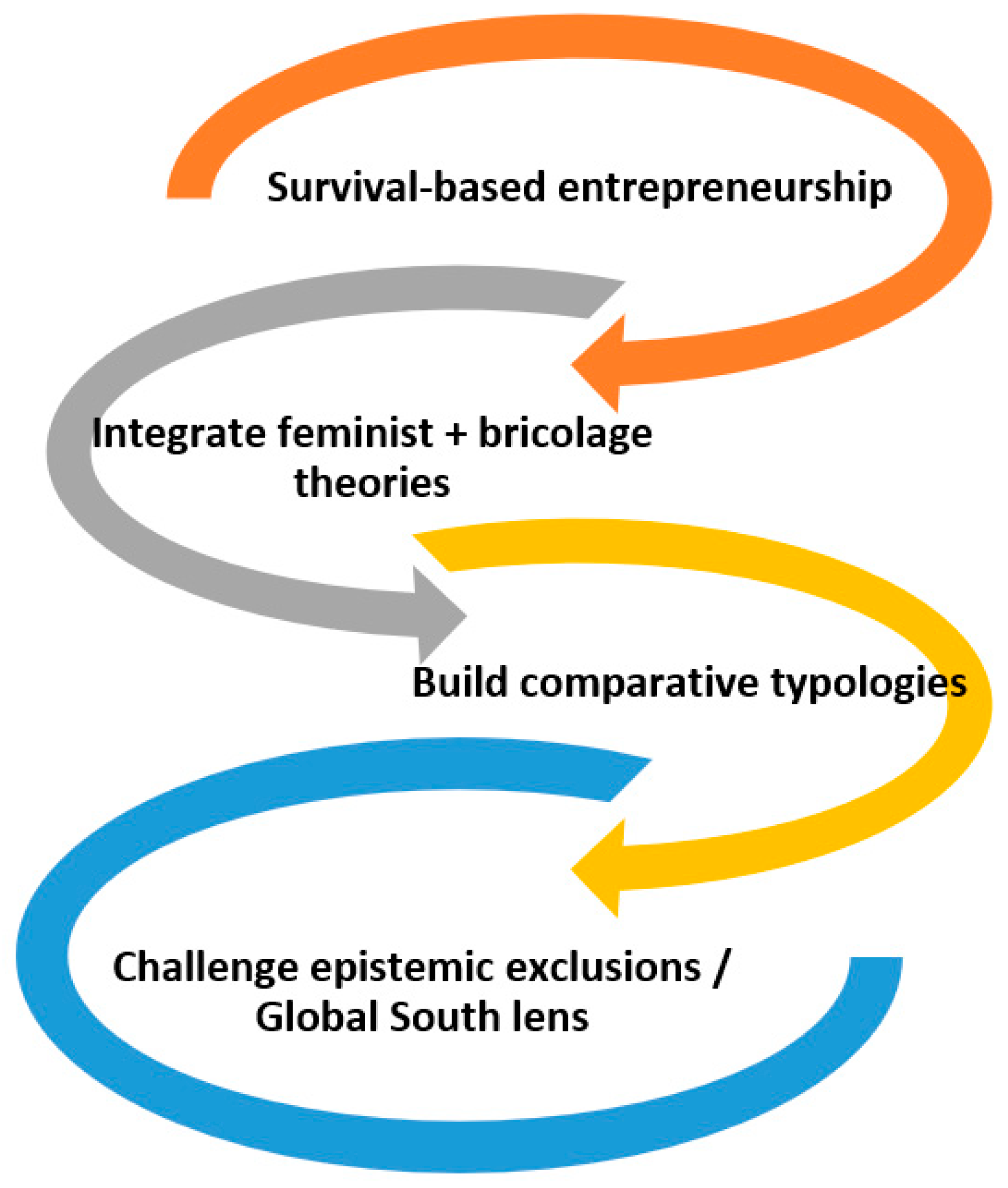

4.5. Toward a Conceptual Agenda for Nanoenterprise Research

- First, nanoenterprises should be distinguished as a category that operates outside the logics of growth, scalability, and formal institutional support. Unlike conventional microenterprises, they are deeply embedded in survival economies, often mediated by gendered labor, spatial marginality, and resource constraints.

- Second, future research should examine nanoenterprises through the lens of entrepreneurship under constraint (Welter et al., 2017), feminist political economy (Benería et al., 2015; Chen, 2012), and resource bricolage (Baker & Nelson, 2005), as these frameworks capture the non-linear, informal, and adaptive dynamics shaping nanoeconomic activity.

- Third, empirical studies should move beyond classification and description toward comparative typologies and translocal analyses, identifying how nanoenterprises differ not just in size, but in their ontological positioning within socioeconomic systems.

- Lastly, the present article calls for more attention to epistemological asymmetries in entrepreneurship research. Nanoenterprises are rarely theorized from the Global South upward, and existing models often fail to account for their systemic invisibility and policy marginalization. A critical engagement with “what counts” as entrepreneurship is thus essential.

5. Conclusions

- Lack of a commonly accepted definition.

- Focus on basic needs on MSMEs.

- Geographical concentration of studies.

- Gender disparities.

- Sectoral limitations.

- Under analyzed transformative potential.

Final Considerations: Epistemic Visibility and Research Inequalities

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Nanoentrepreneur refers to an individual who manages or operates a nanoenterprise—typically a self-employed worker or informal entrepreneur engaged in very small-scale, low-capital business activities. These individuals often lack formal registration, operate in marginalized or rural contexts, and rely on household labor, limited infrastructure, and community-based resources to sustain their ventures (Alvarado Lagunas et al., 2021). |

| 2 | Nanoentrepreneurship refers to the practice of launching and managing extremely small-scale business ventures, typically operated by a single individual or a small family unit, often in informal economic settings. The term is emerging in academic discourse to distinguish this type of subsistence entrepreneurship from larger micro or small enterprises (González Flores, 2015). |

| 3 | Popularized in Mexican digital culture, ‘Nenis’ refers to young female social media vendors (Facebook/WhatsApp). Once pejorative, the term now signifies informal women’s entrepreneurship in precarious urban settings—typically unregistered operations using local delivery methods, exemplifying expanding self-employment patterns in developing economies (Mendoza Guerrero et al., 2024). |

| 4 | NGN stands for Nigerian Naira, which is the official currency of Nigeria (Ola-Akuma & Okocha, 2024). |

| 5 | PAPPS refers to the Programs of Solidarity Economy and Productive Activities (“Programas de Apoio à Produção e à Solidariedade”) promoted by Banco do Nordeste (BNB) in Brazil. These initiatives aim to support micro and nano-scale enterprises through microcredit lines, technical assistance, and the strengthening of community networks, particularly targeting women and marginalized populations in rural and semi-urban areas (Gussi & Thé, 2020). |

References

- Alatas, S. (2022). Knowledge hegemonies and autonomous knowledge. Third World Quarterly, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado Lagunas, E. (2021). Factores condicionantes en la creación informal de nanoempresas: Evidencia experimental en Monterrey, México. Contaduría y Administración (UNAM), 66(3), 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado Lagunas, E., Morales Ramírez, D., & Ortiz Rodríguez, J. (2021). Emprendimiento de nanoempresas en el empoderamiento de mujeres neolonesas. Revista Mexicana de Sociología (UNAM), 82(4), 863–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, T., & Nelson, R. (2005). Creating something from nothing: Resource construction through entrepreneurial bricolage. Administrative Science Quarterly, 50(3), 329–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benería, L., Berik, G., & Floro, M. (2015). Gender, development and globalization: Economics as if all people mattered (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boholm, M. (2016). The use and meaning of nano in American English: Towards a systematic description. Ampersand, 3, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canales-García, R., Juárez Toledo, R., & Rojas Merced, J. (2024). Nanoemprendimiento en el marco de la industria 5.0: Un análisis basado en el método cualitativo de estudio de caso. Cooperativismo & Desarrollo, 32(129). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M. (2012). The informal economy: Definitions, theories and policies. WIEGO working paper No. 1. Available online: https://www.wiego.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Chen_WIEGO_WP1.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- Chuc Pech, F., & Canul Dzul, J. (2024). Estudio de canales de distribución de nanoempresas dedicadas al cultivo de hortalizas de patio trasero en Valladolid, México. Revista Boletín El Conuco, 6(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, R. (2007). Southern theory: The global dynamics of knowledge in social science (1st ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunanan, E., Santos, C., Esguerra, J., Briones, J., & Abante, M. (2025). Relationship between nano-entrepreneurship and employees’ work-life balance in a local government unit in the Philippines. International Journal of Entrepreneurship, Business and Creative Economy, 5(1), 54–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Cunha, J. M., Motta, V., Inácio de Oliveira, A., Bezerra Melo, M. R., & Valente Júnior, A. S. (2025). Microcredit and women’s financial empowerment: Insights from Brazilian crediamigo microcredit program. Journal of Alternative Finance, 2(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, T., & Mehrotra, S. (2019). The size structure of India’s enterprises: Not just the middle is missing. Azim Premji University. Available online: https://publications.azimpremjiuniversity.edu.in/4329/1/Mehrotra_Giri_SizeStructure_IndianEntreprises_December_2019.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- Goncalves, M., & Ahumada, E. (2025). A bibliometric analysis of women entrepreneurship: Current trends and challenges. Merits, 5(2), 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Flores, A. (2015). La nanoempresa como forma de forma de organización económica, su reconocimiento para México. Revista Venezolana De Análisis De Coyuntura, 21(1), 175–186. [Google Scholar]

- Gussi, A., & Thé, R. (2020). Avaliando programas de microcrédito e economia solidária do Banco do Nordeste. Conhecer: Debate Entre O Público E O Privado, 10(24), 164–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halevi, G., Moed, H., & Bar-Ilan, J. (2017). Suitability of Google Scholar as a source of scientific information and as a source of data for scientific evaluation—Review of the Literature. Journal of Informetrics, 11(3), 823–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M., & Tyagi, M. (2025). Political connections and credit access: Evidence from small businesses and microenterprises in India. Small Business Economics, 61, 1463–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ILO. (2017). Employment situation in Latin America and the Caribbean. International Labour Office. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/publications/employment-situation-latin-america-and-caribbean (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- ILO. (2018). Women and men in the informal economy: A statistical picture (3rd ed.). International Labour Office. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/publications/women-and-men-informal-economy-statistical-picture-third-edition (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Ingutia, R., & Sumelius, J. (2024). Does cooperative membership facilitate access to credit for women farmers in rural Kenya? Journal of Agriculture and Food Research, 18, 101425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koporcic, N., Kukkamalla, P., Markovic, S., & Maran, T. (2025). Resilience of small and medium-sized enterprises in times of crisis: An umbrella review. Review of Managerial Science, 1(29). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreiterling, C. (2023). Digital innovation and entrepreneurship: A review of challenges in competitive markets. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 12, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lwesya, F., & Mwakasangula, E. (2023). A scientometric analysis of entrepreneurship research in the age of COVID-19 pandemic. Future Business Journal, 9(1), 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malesu, M., & Syrovátka, P. (2025). Critical success factors for small and medium sized businesses: A PRISMA-based systematic review. Future Business Journal, 11(1), 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Martín, A., Orduna-Malea, E., Thelwall, M., & López-Cózar, E. (2018). Google Scholar, Web of Science, and Scopus: A systematic comparison of citations in 252 subject categories. Journal of Informetrics, 12(4), 1160–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzi, G., Balzano, M., Caputo, A., & Pellegrini, M. (2025). Guidelines for bibliometric-systematic literature reviews: 10 steps to combine analysis, synthesis and theory development. International Journal of Management Reviews, 21, 81–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzarol, T., & Reboud, S. (2020). The role of the small business within the economy. In T. Mazzarol, & S. Reboud (Eds.), Small business management (pp. 1–29). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza Guerrero, D., Alcántara Hernández, R., & Vega Barrios, A. (2024). Las nenis: Estrategias de mercadotecnia en el nano emprendimiento femenino mexicano. Ciencia Latina Revista Científica Multidisciplinar, 8(6), 3167–3185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T., Phillipson, J., Wishart, M., Roper, S., & Gorton, M. (2025). Understanding rural business resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Rural Studies, 104, 103580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordbø, I. (2022). Female entrepreneurs and path-dependency in rural tourism. Journal of Rural Studies, 96, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ola-Akuma, R., & Okocha, D. (2024). valuating the Gender-Inclusive Uptake of New Media Platforms by Nano and Micro Enterprises in Kano State Nigeria. Journal of Development Communication, 35(1), 21–35. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., & Chou, R. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parthiban, R., Sun, R., Qureshi, I., & Bandyopadhyay, S. (2024). Empowering rural micro-entrepreneurs through technoficing: A process model for mobilizing and developing indigenous knowledge. The Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 33(2), 101836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Medina, O., Alvarado Lagunas, E., & Sánchez Silva, M. (2023). Informalidad y nanoempresas en localidades perimetropolitanas de la Ciudad de México. Problemas del Desarrollo. Revista Latinoamericana de Economía (UNAM-IIEC), 54(212), 55–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Vera, A., Rando-Cueto, D., & De las Heras Pedrosa, C. (2025). Women’s entrepreneurship in the tourism industry: A bibliometric study. Administrative Sciences, 15(4), 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saavedra, A. (2024). The role of female-only business networks in rural development: Evidence from NSW, Australia. Journal of Rural Studies, 106, 103236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, B. (2014). Epistemologies of the South: Justice against epistemicide (1st ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarasvathy, S. D. (2001). Causation and effectuation: Toward a theoretical shift from economic inevitability to entrepreneurial contingency. Academy of Management Review, 26(2), 243–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulaiman, M., Isa, F., Ahmed Tanimu, L., Rilwanand, B., & Moukhtar, M. (2023). The effect of Naira redesign policy on the wellbeing of nano and micro scale enterprises in northern Nigeria. Jalingo Journal of Social and Management Sciences, 5(1), 182–199. [Google Scholar]

- Teka, B. (2022). Determinants of the sustainability and growth of micro and small enterprises (MSEs) in Ethiopia: Literature review. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 11(1), 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia-Sandoval, K., Rojas-Rojas, M., & Corichi-García, A. (2023). Problemas de los nanoempresarios en pandemia. Un análisis factorial exploratorio. Vinculatégica EFAN, 9(1), 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welter, F. (2011). Contextualizing entrepreneurship—Conceptual challenges and ways forward. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 35(1), 165–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welter, F., Baker, T., Audretsch, D., & Gartner, W. (2017). Everyday entrepreneurship—A call for entrepreneurship research to embrace entrepreneurial diversity. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 41(3), 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Criteria | Nanoenterprise | Microenterprise | Necessity Entrepreneurship | Informal Worker |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Legal registration | No | Often yes | Variable | Mostly no |

| Labor structure | Self/family (1–2 people) | 1–10 employees | Self-employed | Wage labor (unregulated) |

| Capital intensity | Very low | Low to moderate | Low | Very low |

| Goal | Survival, subsistence | Growth or stability | Income generation | Income/wage |

| Market strategy | Local, social/family | Regional/local markets | Mixed | Depends on sector |

| Formal ecosystem access | None or limited | Partial to full | Partial | None |

| Journal Name | JCR/WOS/Scopus/SJR Indexing | Quartile (If Applicable) | Impact Factor (If Applicable) | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Revista Boletín El Conuco | Not indexed | N/A | N/A | Colombia |

| Revista Venezolana de Análisis de Coyuntura | Not indexed | N/A | Not reported | Venezuela |

| Jalingo Journal of Social and Management Sciences | Not indexed | N/A | N/A | Nigeria |

| Contaduría y Administración (UNAM) | Scopus (Q3), SJR (Q2 in Economics) | Q3 (Scopus), Q2 (SJR) | SJR 2022: 0.24 (Scopus) | Mexico |

| Revista Mexicana de Sociología (UNAM) | Scopus (Q2 in Sociology), WOS (ESCI) | Q2 (Scopus) | SJR 2022: 0.38 (Scopus) | Mexico |

| Problemas del Desarrollo. Revista Latinoamericana de Economía (UNAM-IIEC) | Scopus (Q3 in Economics), WOS (ESCI) | Q3 (Scopus) | SJR 2022: 0.29 (Scopus) | Mexico |

| Journal of Development Communication | Not indexed | N/A | N/A | Malaysia |

| Conhecer: Debate Entre O Público E O Privado | Not indexed | N/A | Not reported | Brazil |

| Cooperativismo & Desarrollo | Not indexed | N/A | Not reported | Colombia |

| Vinculatégica EFAN | Not indexed | N/A | Not reported | Mexico |

| Ciencia Latina Revista Científica Multidisciplinar | Not indexed | N/A | Not reported | Mexico |

| International Journal of Entrepreneurship, Business and Creative Economy (IJEBCE) | Not indexed | N/A | Not reported | Indonesia (editorial Research Synergy Press) |

| Ref. | Journal Name | Country of Study | Publication Language | Citations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Alvarado Lagunas et al., 2021) | Revista Mexicana de Sociología (UNAM) | Mexico | Spanish | 18 |

| (Alvarado Lagunas, 2021) | Contaduría y Administración (UNAM) | Mexico | Spanish/English | 16 |

| (González Flores, 2015) | Revista Venezolana de Análisis de Coyuntura | Mexico | Spanish | 16 |

| (Rodríguez Medina et al., 2023) | Problemas del Desarrollo. Revista Latinoamericana de Economía (UNAM-IIEC) | Mexico | Spanish/English | 7 |

| (Valencia-Sandoval et al., 2023) | Vinculatégica EFAN | Mexico | Spanish | 2 |

| (Sulaiman et al., 2023) | Jalingo Journal of Social and Management Sciences | Nigeria | English | 1 |

| (Gussi & Thé, 2020) | Conhecer: Debate Entre O Público E O Privado | Brazil | English/Portuguese | 1 |

| (Chuc Pech & Canul Dzul, 2024) | Revista Boletín El Conuco | Mexico | Spanish | 0 |

| (Ola-Akuma & Okocha, 2024) | Journal of Development Communication | Nigeria | English | 0 |

| (Canales-García et al., 2024) | Cooperativismo & Desarrollo | Mexico | Spanish | 0 |

| (Cunanan et al., 2025) | International Journal of Entrepreneurship, Business and Creative Economy | Philippines | English | 0 |

| (Mendoza Guerrero et al., 2024) | Ciencia Latina Revista Científica Multidisciplinar | Mexico | Spanish | 0 |

| Ref. | Key Themes | Methodological Approach | Sectoral Focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Chuc Pech & Canul Dzul, 2024) | Agricultural distribution and commercialization. | Empirical (mixed methods) | Agriculture (backyard farming) |

| (González Flores, 2015) | Conceptual framework and policy recognition. | Theoretical-conceptual | Multisectoral (international comparison) |

| (Sulaiman et al., 2023) | Monetary policy and business welfare. | Empirical (quantitative/qualitative) | Informal food trade |

| (Alvarado Lagunas, 2021) | Formalization and informal entrepreneurship. | Experimental (intervention-based) | Urban informal services |

| (Alvarado Lagunas et al., 2021) | Female empowerment and training. | Experimental (gender-focused) | Urban informal trade |

| (Rodríguez Medina et al., 2023) | Informality and spatial dynamics. | Empirical (spatial-statistical) | Trade and services |

| (Ola-Akuma & Okocha, 2024) | Digital inclusion and gender gaps. | Quantitative (surveys) | E-commerce and ICT |

| (Gussi & Thé, 2020) | Microfinance and social economy. | Qualitative (ethnographic) | Social and solidarity economy |

| (Canales-García et al., 2024) | Schumpeterian nanoentrepreneurship; innovation; cooperation networks. | Qualitative (Case Study) | Automotive (Industry 5.0) |

| (Cunanan et al., 2025) | Work–life balance; dual roles; nanoenterprises as secondary income. | Quantitative (surveys) | Public workers’ side-businesses |

| (Mendoza Guerrero et al., 2024) | “NENIS3” concept; informal marketing via social media; gendered empowerment. | Quantitative (surveys) | Beauty, food, apparel |

| (Valencia-Sandoval et al., 2023) | Challenges during COVID-19; finance, insecurity, inflation; validated instrument. | Quantitative (EFA) | Informal trade during pandemic |

| Thematic Category | Keywords Included | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Nanoenterprise (concept) | Nanoempresas (nanoenterprises), nanoempresario (nanoentrepreneur), nano enterprises, nano-businesses | 11 |

| Informality | Informalidad (informality), economía informal (informal economy), informal business status, transition to a formal business | 5 |

| Microenterprise | Micro-enterprises, employment | 2 |

| Gender and empowerment | Empoderamiento (empowerment), poder de decisión de las mujeres (women’s decision-making power), gender | 3 |

| Agriculture/Local trade | Hortalizas (vegetables), plaza (marketplace), canales (distribution channels), distribución (distribution), minoristas (retail) | 1 |

| Digital inclusion | Digital technologies, new media | 2 |

| Policy and support | Public policy, microcredit, solidarity economy, development bank | 4 |

| Theorical concepts | Organización (organization), sistema abierto (open system), enfoque de procesos (process approach) | 4 |

| Analytical Axis | Related Research Question (RQs) |

|---|---|

| 3.2.1. Definitional and Conceptual Boundaries of Nanoenterprises | RQ1: How has the concept of nanoenterprises evolved in the scientific literature? RQ2 (part): What distinguishes nanoenterprises from micro- and small businesses? |

| 3.2.2. Sectoral and Geographical Patterns | RQ3: In which sectors have nanoenterprises developed most? RQ2 (part): How do nanoenterprises differ contextually across sectors? |

| 3.2.3. Intersectional Challenges: Gender, Digital Access, and Exclusion | RQ4: What challenges do women nanoentrepreneurs face, and what strategies have proven effective for their inclusion? |

| Ref. | Country of Study | Nanoenterprise Definition |

|---|---|---|

| (Chuc Pech & Canul Dzul, 2024) | Mexico | Rural business with no employees, local resources, informal economy. |

| (González Flores, 2015) | Mexico | Single-person unit, informal, no tax registration. |

| (Sulaiman et al., 2023) | Nigeria | Unregistered business, income < 3M NGN4/year. |

| (Alvarado Lagunas, 2021) | Mexico | Individual without labor contract or legal registration. |

| (Rodríguez Medina et al., 2023) | Mexico | Family unit of ≤3 people, no tax registration, precarious income. |

| (Canales-García et al., 2024) | Mexico | Portrayed as innovation-driven ventures operating, typically involving 1–2 individuals, often family-based. |

| (Cunanan et al., 2025) | Philippines | Informal, side-venture businesses initiated by public workers to generate supplemental income; typically, individually operated with minimal capital and no formal registration. |

| (Mendoza Guerrero et al., 2024) | Mexico | Defined implicitly through the concept of “NENIS” as ultra-small, informally operating women-led businesses using social media platforms for sales, often lacking physical premises and operating individually or within household spaces. |

| (Valencia-Sandoval et al., 2023) | Mexico | Framed as part of the informal trade sector, operated by individuals in highly precarious economic conditions with very limited financial, social, and technological resources. |

| Part A: Nanoenterprises’ characteristics identified in the reviewed articles (Systematic Corpus) | |||

| Criteria | Nanoenterprise | Ref. | |

| Size (people) | 1–3 people, often self-employed or family-run. | (Mendoza Guerrero et al., 2024; Rodríguez Medina et al., 2023) | |

| Legal status | Predominantly informal, no tax registration. | (Alvarado Lagunas, 2021) | |

| Capital/Income | Subsistence-level, minimal capital. | (Chuc Pech & Canul Dzul, 2024) | |

| Operational modality | Home-based, informal street or backyard work. | (Valencia-Sandoval et al., 2023) | |

| Market scope | Local, community-oriented. | (Cunanan et al., 2025) | |

| Part B: Conceptual comparison based on complementary literature (Not part of systematic corpus) | |||

| Criteria | Nanoenterprise (Based on Systematic Corpus literature included on Part A) | Microbusiness (Hussain & Tyagi, 2025) | Small Business (Giri & Mehrotra, 2019; Mazzarol & Reboud, 2020) |

| Size (people) | 1–3 people | Up to 10 employees (OECD/EU definition). | 11–49 employees (OECD/EU) |

| Legal formalization | Typically, informal | May be registered or not; in formalization process. | Typically formalized, with defined legal structure |

| Capital/annual income | <10,000 USD/year (estimated). | Moderate; income varies by context. 10,000–100,000 USD/year. | Stable income, access to credit/financing. >100,000 USD/year. |

| Operational modality | Individual or family-based, home-based or informal space. | Family or individual, may operate in local markets. | Structured operations with hired staff and physical location. |

| Access to financial services | Limited or nonexistent. | Partial, with restrictions. | Broader access to credit, insurance, and accounting systems. |

| Market coverage | Local or community-level. | Local or regional. | Regional or national. |

| Example sectors | Street vending, personal services, backyard agriculture. | Workshops, retail, fast food. | Manufacturing, logistics, specialized trade. |

| Sector | Ref. | Countries | Approximate % of Total Articles |

|---|---|---|---|

| Informal trade | (Rodríguez Medina et al., 2023); (Alvarado Lagunas et al., 2021); (Ola-Akuma & Okocha, 2024); (Valencia-Sandoval et al., 2023) | Mexico, Nigeria | 33.3% |

| Personal services | (Alvarado Lagunas, 2021); (Ola-Akuma & Okocha, 2024); (Mendoza Guerrero et al., 2024) | Mexico, Nigeria | 25% |

| Rural agriculture | (Chuc Pech & Canul Dzul, 2024); (Cunanan et al., 2025) | Mexico, Philippines | 16.7% |

| Solidarity economy | (Gussi & Thé, 2020), (Canales-García et al., 2024) | Brazil, Mexico | 16.7% |

| Digital commerce/ICT | (Ola-Akuma & Okocha, 2024) | Nigeria | 8.3% |

| Strategy | Observed Outcomes | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| Gender-focused training | 31.4% increase in self-confidence, 39.8% higher business formalization rate. | (Rodríguez Medina et al., 2023) |

| Solidarity microcredit (BNB program) | Strengthened community networks, 80% of women reported political empowerment. | (Gussi & Thé, 2020) |

| Family-based distribution networks (Yucatán) | Enabled product commercialization without formal market dependence. | (Chuc Pech & Canul Dzul, 2024) |

| Social media adoption | Limited but growing impact, Most prevalent among young women with secondary education. | (Ola-Akuma & Okocha, 2024) |

| Digital micro-enterprise training | Improved business formalization and digital skill acquisition among rural women. | (Canales-García et al., 2024) |

| Cooperative-based marketing platforms | Enhanced visibility of women’s informal businesses, improved negotiation capacity. | (Mendoza Guerrero et al., 2024) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ramírez-López, K.P.; Hernández-López, M.S.; Herrera-Ruiz, G.; García-Trejo, J.F.; Mendoza-Sánchez, M.; Nieto-Ramírez, M.I.; Rodríguez-Reséndiz, J. Female-Led Rural Nanoenterprises in Business Research: A Systematic and Bibliometric Review of an Overlooked Entrepreneurial Category. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 321. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15080321

Ramírez-López KP, Hernández-López MS, Herrera-Ruiz G, García-Trejo JF, Mendoza-Sánchez M, Nieto-Ramírez MI, Rodríguez-Reséndiz J. Female-Led Rural Nanoenterprises in Business Research: A Systematic and Bibliometric Review of an Overlooked Entrepreneurial Category. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(8):321. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15080321

Chicago/Turabian StyleRamírez-López, Karen Paola, Ma. Sandra Hernández-López, Gilberto Herrera-Ruiz, Juan Fernando García-Trejo, Magdalena Mendoza-Sánchez, María Isabel Nieto-Ramírez, and Juvenal Rodríguez-Reséndiz. 2025. "Female-Led Rural Nanoenterprises in Business Research: A Systematic and Bibliometric Review of an Overlooked Entrepreneurial Category" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 8: 321. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15080321

APA StyleRamírez-López, K. P., Hernández-López, M. S., Herrera-Ruiz, G., García-Trejo, J. F., Mendoza-Sánchez, M., Nieto-Ramírez, M. I., & Rodríguez-Reséndiz, J. (2025). Female-Led Rural Nanoenterprises in Business Research: A Systematic and Bibliometric Review of an Overlooked Entrepreneurial Category. Administrative Sciences, 15(8), 321. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15080321