Rising Like a Phoenix: A Bibliometric and Content Analysis of the Regeneration Concept in Business Studies

Abstract

1. Introduction

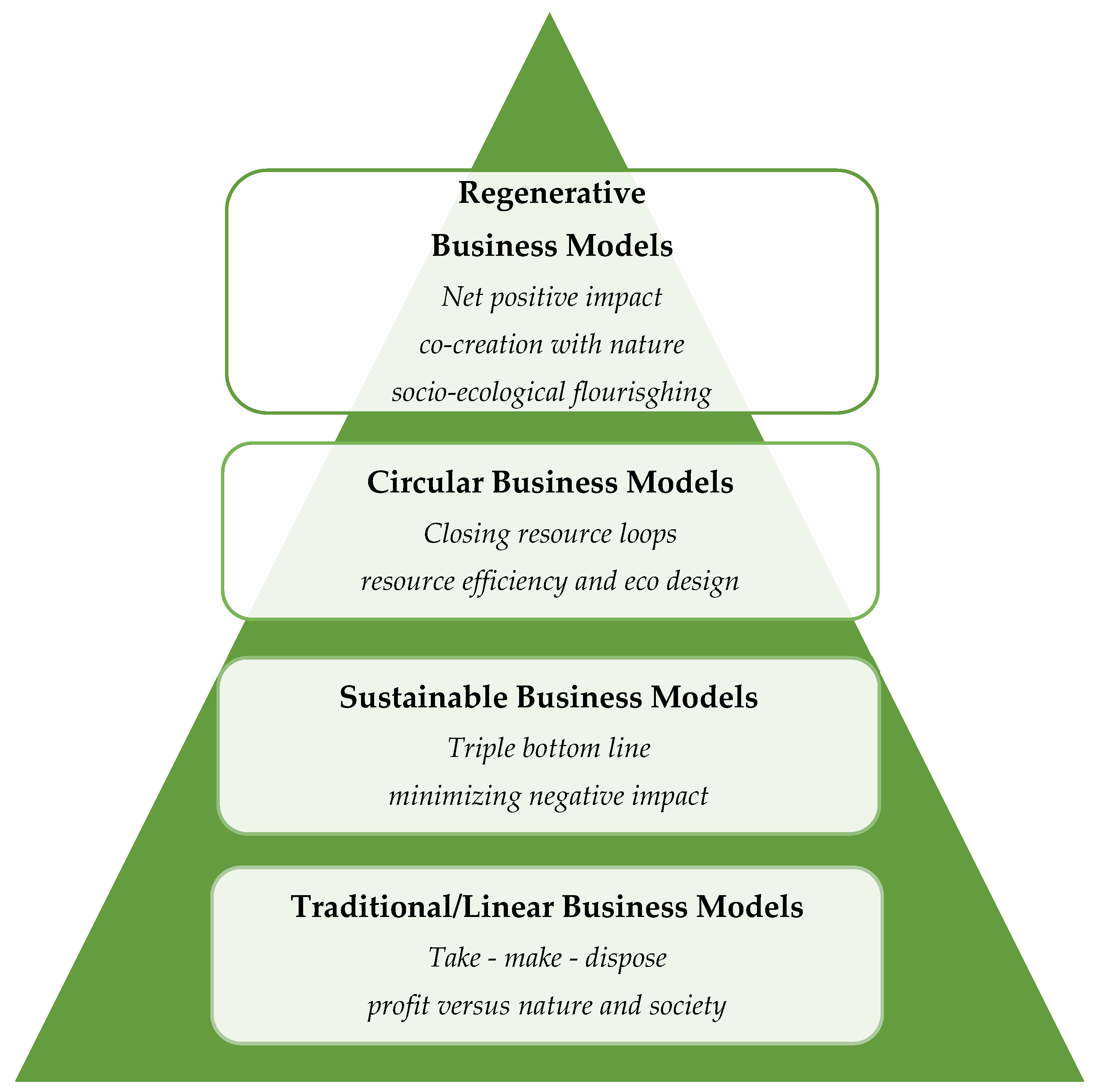

2. Regeneration and Regenerative Business/Business Models

The Evolution of Regenerative Business Models

- SBMs aim to reduce the ecological and social footprint of business activities.

- CBMs strive to close, slow, and narrow resource loops, to create resource-efficient and self-sustaining systems (Bocken et al., 2016).

- RBMs extend beyond both SBMs and CBMs by actively restoring and regenerating ecosystems and communities.

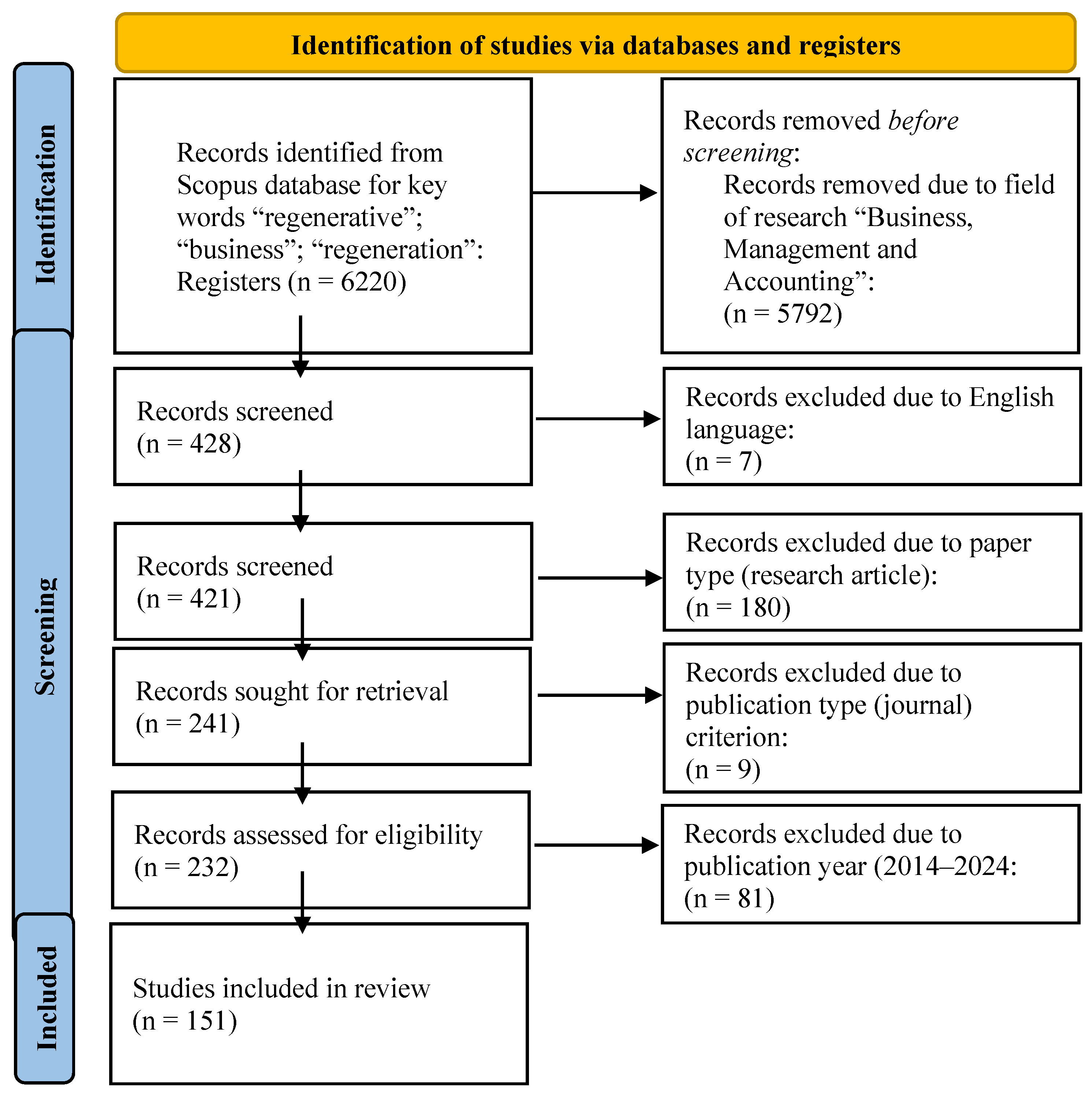

3. Methodological Approach

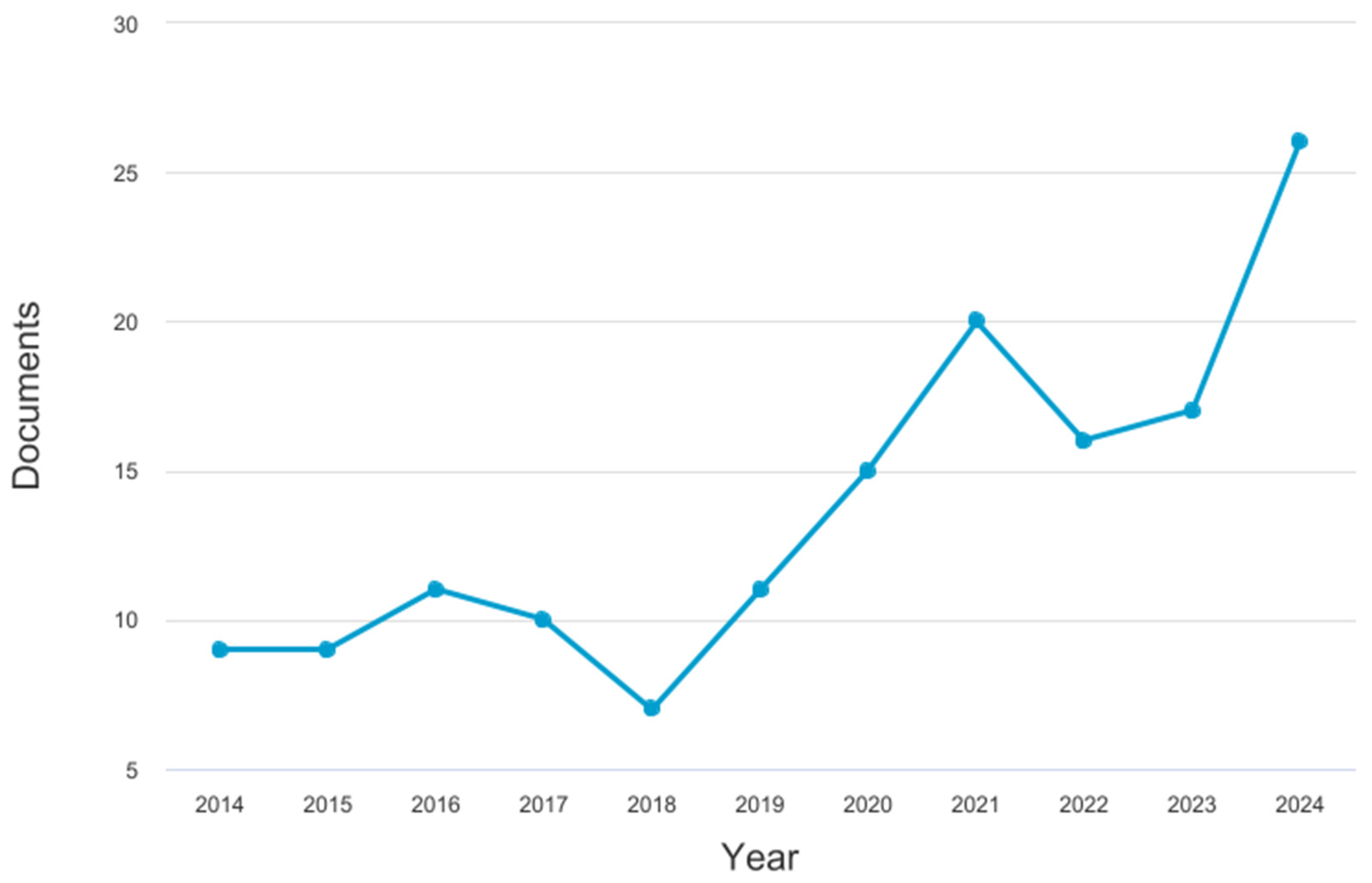

4. Results

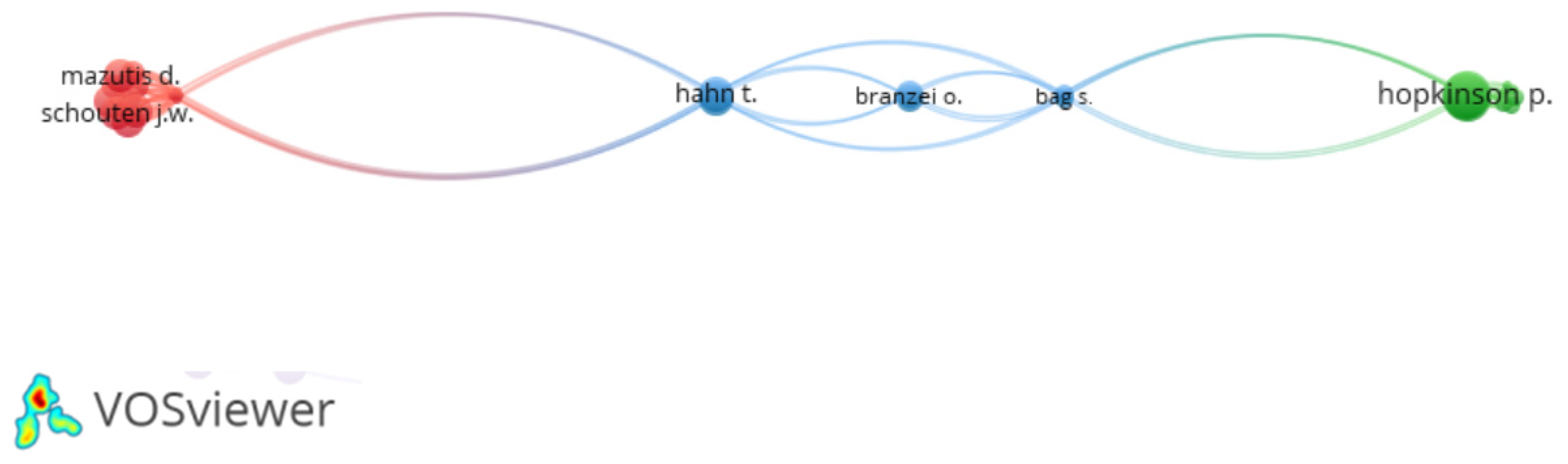

4.1. RO1: Citations Analysis Based on Documents and Authors

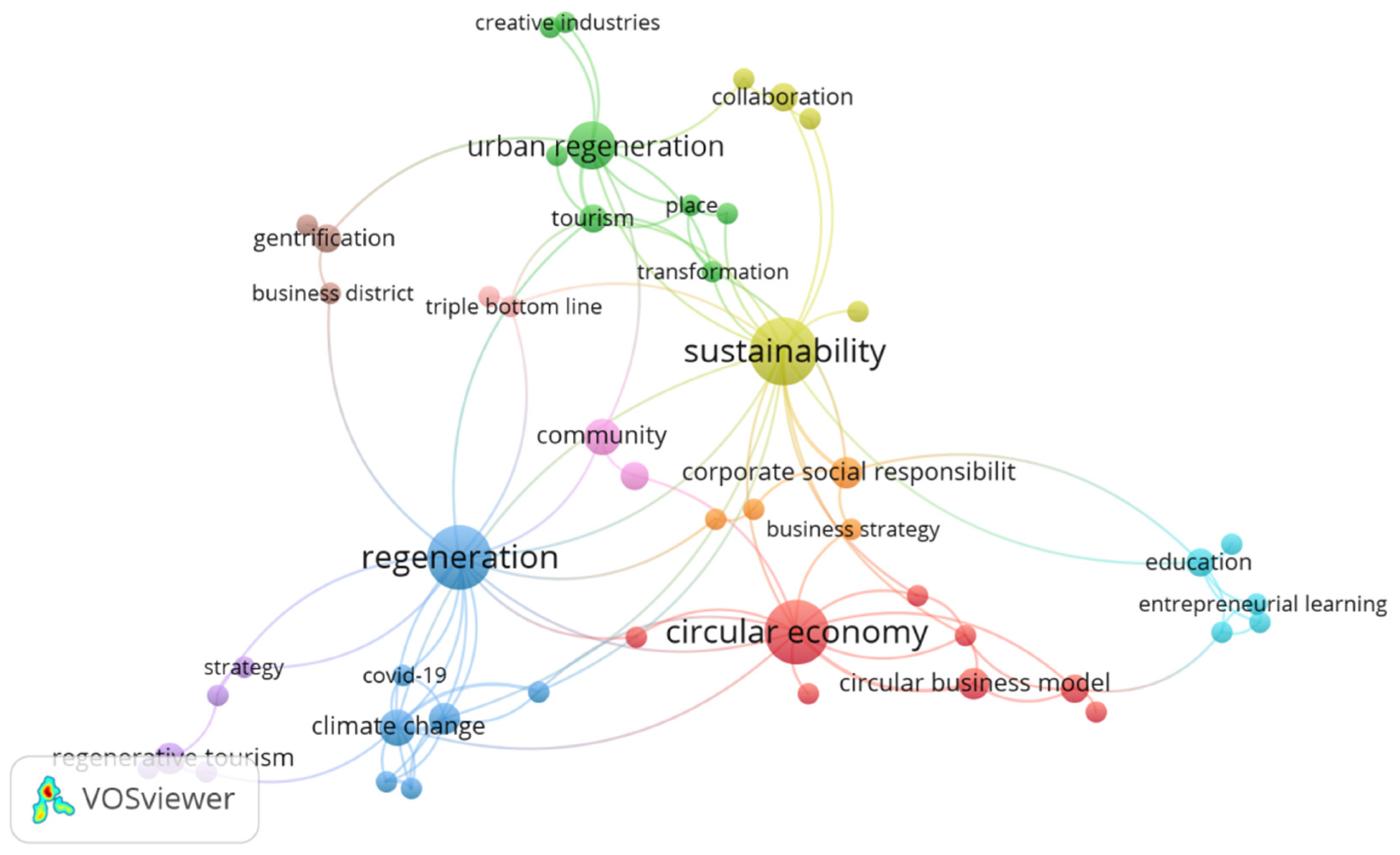

4.2. RO2: Keywords—Cluster Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Implications

7. Limitations and Future Research Avenues

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | up to 30 August 2024. |

References

- Aoustin, E. (2023). Regenerative leadership: What it takes to transform business into a force for good. Field Actions Science Reports. The Journal of Field Actions, 25, 92–97. [Google Scholar]

- Bag, S., & Rahman, M. S. (2023). Navigating circular economy: Unleashing the potential of political and supply chain analytics skills among top supply chain executives for environmental orientation, regenerative supply chain practices, and supply chain viability. Business Strategy and the Environment, 33(2), 504–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N. M. P., De Pauw, I., Bakker, C., & Van der Grinten, B. (2016). Product design and business model strategies for a circular economy. Journal of Industrial and Production Engineering, 33(5), 308–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boluk, K. A., & Panse, G. (2022). Recognising the regenerative impacts of Canadian women tourism social entrepreneurs through a feminist ethic of care lens. Journal of Tourism Futures, 8(3), 352–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boons, F., & Lüdeke-Freund, F. (2013). Business models for sustainable innovation: State-of-the-art and steps towards a research agenda. Journal of Cleaner Production, 45, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, B. M. (2011). Principles of regenerative biology. Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Caruso, L. (2023). Toward regenerative hospitality business models: The case of “Hortel”. Tourism and Hospitality, 4(4), 618–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centre for Science and Technology Studies. (n.d.). VOSviewer manual (Version 1.6.8). Leiden University. pp. 8, 11, 13.

- Corral-Gonzalez, L., Cavazos-Arroyo, J., & García-Mestanza, J. (2023). Regenerative tourism: A bibliometric analysis. Journal of Tourism, Heritage & Services Marketing, 9(2), 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubillas-Para, C., Cegarra-Navarro, J. G., & Vătămănescu, E.-M. (2024). Gliding from regenerative unlearning toward digital transformation via collaboration with customers and organisational agility. Journal of Business Research, 177, 114637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amato, D., Droste, N., Allen, B., Kettunen, M., Lähtinen, K., Korhonen, J., Leskinen, P., Matthies, B. D., & Toppinen, A. (2017). Green, circular, bio economy: A comparative analysis of sustainability avenues. Journal of Cleaner Production, 168, 716–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A., & Bocken, N. (2024). Regenerative business strategies: A database and typology to inspire business experimentation towards sustainability. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 49, 529–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delconte, J., Kline, C. S., & Scavo, C. (2015). The impacts of local arts agencies on community placemaking and heritage tourism. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 11(4), 324–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- den Hollander, M., & Bakker, C. (2016). Mind the gap exploiter: Circular business models for product lifetime extension. In Electronics Goes Green 2016+: Inventing Shades of Green (pp. 1–8). Fraunhofer IZM Berlin. [Google Scholar]

- Drupsteen, L., & Wakkee, I. (2024). Exploring characteristics of regenerative business models through a Delphi inspired approach. Sustainability, 16(7), 3062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Plessis, C., & Cole, R. (2011). Motivating change: Shifting the paradigm. Building Research & Information, 39(5), 436–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyllick, T., & Hockerts, K. (2002). Beyond the business case for corporate sustainability. Business Strategy and the Environment, 11(2), 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullerton, J. (2015). Regenerative capitalism: How universal principles and patterns will shape our new economy. Capital Institute. Available online: https://capitalinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/2015-Regenerative-Capitalism-4-20-15-final.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Geissdoerfer, M., Bocken, N. M. P., & Hultink, E. J. (2016). Design thinking to enhance the sustainable business modelling process—A workshop based on a value mapping process. Journal of Cleaner Production, 135, 1218–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissdoerfer, M., Savaget, P., Bocken, N. M. P., & Hultink, E. J. (2017). The circular economy—A new sustainability paradigm? Journal of Cleaner Production, 143, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, R., Sharma, H., & Sharma, A. (2023). A thorough examination of organizations from an ethical viewpoint: A bibliometric and content analysis of organizational virtuousness studies. Business Ethics, the Environment & Responsibility, 33(1), 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, T., & Tampe, M. (2021). Strategies for regenerative business. Strategic Organization, 19(3), 456–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Franco, G., Montalván-Burbano, N., Carrión-Mero, P., Apolo-Masache, B., & Jaya-Montalvo, M. (2020). Research trends in geotourism: A bibliometric analysis using the Scopus database. Geosciences, 10(10), 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, F., & Jaeger-Erben, M. (2020). Organizational transition management of circular business model innovations. Business Strategy and the Environment, 29(6), 2770–2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, M., Hopkinson, P., & Miemczyk, J. (2019). The regenerative supply chain: A framework for developing circular economy indicators. International Journal of Production Research, 57(23), 7300–7318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliev, D. (2021). Urban regeneration and changes driven by tourism and the “Skopje 2014” project. Transylvanian Review of Administrative Sciences, 62, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inversini, A., Saul, L., Balet, S., & Schegg, R. (2024). The rise of regenerative hospitality. Journal of Tourism Futures, 10(1), 6–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M. W., Christensen, C. M., & Kagermann, H. (2008). Reinventing your business model. Harvard Business Review, 86(12), 57–68. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J. (2016). Cultural entrepreneurs and urban regeneration in Itaewon, Seoul. Cities, 56, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konietzko, J., Das, A., & Bocken, N. (2023). Towards regenerative business models: A necessary shift? Sustainable Production and Consumption, 38, 372–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippendorff, K. (2018). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Laszlo, C., Cooperrider, D., & Fry, R. (2021). Business innovation as a force for good: From doing less harm to positive impact type 1 and type 2. Business and Society Review, 2, 168–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C., Jin, Y., & Homapour, E. (2023). A scientometric review of hotspots and emerging trends in sustainable business model. Heliyon, 9, e18446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linder, M., & Williander, M. (2017). Circular business model innovation: Inherent uncertainties. Business Strategy and the Environment, 26(2), 182–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, M. P., & Siegel, D. (2019). A bibliometric analysis of employee-centred corporate social responsibility research in the 2000s. Social Responsibility Journal, 16(5), 691–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R. (2018). Sustainable business models: Providing a more holistic perspective. Business Strategy and the Environment, 27(8), 1159–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lueg, R., Pedersen, M. M., & Clemmensen, S. N. (2015). The role of corporate sustainability in a low-cost business model—A case study in the Scandinavian fashion industry. Business Strategy and the Environment, 24(5), 344–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahadevan, K. (2017). Culture driven regeneration (CDR): A conceptual business improvement tool. The TQM Journal, 29(2), 403–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mang, P., & Haggard, B. (2016). Regenerative development and design: A framework for evolving sustainability. Wiley. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manniche, J., Larsen, K. T., & Broegaard, R. B. (2021). The circular economy in tourism: Transition perspectives for business and research. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 21(3), 247–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzi, G., Balzano, M., Caputo, A., & Pellegrini, M. M. (2024). Guidelines for bibliometric-systematic literature reviews: 10 steps to combine analysis, synthesis and theory development. International Journal of Management Reviews, 27(1), 81–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayring, P. (2014). Qualitative content analysis: Theoretical foundation, basic procedures and software solution. University of Klagenfurt. Available online: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-395173 (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- Meier, O., Gruchmann, T., & Ivanov, D. (2023). Circular supply chain management with blockchain technology: A dynamic capabilities view. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review, 176(1), 103177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mentink, B. A. S. (2014). Circular business model innovation: A process framework and a tool for business model innovation in a circular economy [Master’s thesis, Delft University of Technology]. Available online: https://resolver.tudelft.nl/uuid:c2554c91-8aaf-4fdd-91b7-4ca08e8ea621 (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- Mishra, A., Verma, P., & Tiwari, M. K. (2021). A circularity-based quality assessment tool to classify the core for recovery businesses. International Journal of Production Research, 60(19), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, D., Lim, W. M., Kumar, S., & Donthu, N. (2022). Guidelines for advancing theory and practice through bibliometric research. Journal of Business Research, 148, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, P., & Branzei, O. (2021). Regenerative organizations: Introduction to the special issue. Organization & Environment, 34(4), 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, T. H., Kawuki, J., & Musa, H. H. (2022). Bibliometric analysis of the African Health Sciences’ research indexed in Web of Science and Scopus. African Health Sciences, 22(2), 704–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosratabadi, S., Mosavi, A., Shamshirband, S., Zavadskas, E. K., Rakotonirainy, A., & Chau, K. W. (2019). Sustainable business models: A review. Sustainability, 11(6), 1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterwalder, A., & Pigneur, Y. (2010). Business model generation: A handbook for visionaries, game changers, and challengers. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., & Chou, R. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palakshappa, N., Venkateswar, S., & Ganesh, S. (2023). Broadening the circle: Creativity, regeneration and redistribution in value loops. Social Responsibility Journal, 19(10), 1870–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, H. C., Mackay, M., & Wilson, J. (2023). Community-led heritage conservation in processes of rural regeneration. Journal of Place Management and Development, 16(3), 367–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polman, P., & Winston, A. (2021). Net positive: How courageous companies thrive by giving more than they take. Harvard Business Review Press. [Google Scholar]

- Raworth, K. (2017). Doughnut economics: Seven ways to think like a 21st-century economist. Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Roos, G. (2014). Business model innovation to create and capture resource value in future circular material chains. Resources, 3(1), 248–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, A., & Zheng, Y. (2021). A tale of two food chains: The duality of practices on well-being. Production and Operations Management, 30(3), 783–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaltegger, S., Hansen, E. G., & Lüdeke-Freund, F. (2016). Business models for sustainability: Origins, present research, and future avenues. Organization & Environment, 29(1), 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shand, R. (2014). Community management of regeneration projects in Potsdam, Germany. International Journal of Law and Management, 56(3), 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherwood, M. W., & Pollard, J. (2023). Responsible investing: An introduction to environmental, social, and governance investments (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R. K. (2024). Exploring the impact of green supply chain strategies and sustainable practices on circular supply chains. Benchmarking: An International Journal. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slawinski, N., Winsor, B., Mazutis, D., Schouten, J. W., & Smith, W. K. (2021). Managing the paradoxes of place to foster regeneration. Organization & Environment, 34(4), 595–618. [Google Scholar]

- Starik, M., Stubbs, W., & Benn, S. (2016). Synthesising environmental and socio-economic sustainability models: A multi-level approach for advancing integrated sustainability research and practice. Australasian Journal of Environmental Management, 23(4), 402–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stubbs, W. (2017). Characterising B Corps as a sustainable business model: An exploratory study of B Corps in Australia. Journal of Cleaner Production, 144, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunny, S. A. (2021). Nature cannot be fooled: A dual-equilibrium simulation of climate change. Organization & Environment, 34(4), 619–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiep, T. L., Behl, A., & Graham, G. (2023). The role of entrepreneurship in successfully achieving circular supply chain management. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management, 24(4), 537–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, N. J., & Waltman, L. (2010). Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics, 84(2), 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, N. J., & Waltman, L. (2023). VOSviewer manual (Version 1.6.19). Centre for Science and Technology Studies.

- Vlasov, M. (2021). In transition toward the ecocentric entrepreneurship nexus: How nature helps entrepreneurs make venture more regenerative over time. Organization & Environment, 34(4), 559–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddock, S., Henriques, I., Linnenluecke, M., Poggioli, N., & Böhm, S. (2024). The paradigm shift: Business associations shaping the discourse on system change. Business and Society Review, 129(2), 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, P., Kern, M. L., & Waters, L. (2017). The role and reprocessing of attitudes in fostering employee work happiness: An intervention study. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, S. (2015). Artists and Shanghai’s culture-led urban regeneration. Cities, 56, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Title | Authors | Citations | Links |

|---|---|---|---|

| Howard et al. (2019) | 136 | 3 |

| Hahn and Tampe (2021) | 51 | 3 |

| Slawinski et al. (2021) | 45 | 1 |

| Muñoz and Branzei (2021) | 23 | 2 |

| Roth and Zheng (2021) | 15 | 1 |

| Boluk and Panse (2022) | 12 | 1 |

| Bag and Rahman (2023) | 8 | 3 |

| Mishra et al. (2021) | 6 | 1 |

| Inversini et al. (2024) | 1 | 4 |

| Palakshappa et al. (2023) | 1 | 1 |

| No | Keyword | Occurrences | Total Link Strength |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Sustainability | 18 | 18 |

| 2. | Regeneration | 16 | 15 |

| 3. | Circular Economy | 16 | 13 |

| 4. | Urban Regeneration | 9 | 11 |

| 5. | Climate Change | 5 | 12 |

| 6. | Community | 5 | 3 |

| 7. | Corporate Social Responsibility | 4 | 6 |

| 8. | Circular Business Model | 4 | 4 |

| 9. | Regenerative Tourism | 4 | 3 |

| 10. | Tourism | 3 | 8 |

| 11. | Education | 3 | 6 |

| 12. | Collaboration | 3 | 3 |

| 13. | Gentrification | 3 | 3 |

| 14. | Transformation | 2 | 5 |

| 15. | Place | 2 | 4 |

| 16. | Triple Bottom Line | 2 | 4 |

| 17. | COVID-19 | 2 | 3 |

| 18. | Entrepreneurial Learning | 2 | 3 |

| 19. | Business District | 2 | 2 |

| 20. | Business Strategy | 2 | 2 |

| 21. | Creative Industries | 2 | 2 |

| 22. | Strategy | 2 | 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Glaveli, N.; Voulgari, V.; Daskalopoulou, A.; Poulaki, I. Rising Like a Phoenix: A Bibliometric and Content Analysis of the Regeneration Concept in Business Studies. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 316. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15080316

Glaveli N, Voulgari V, Daskalopoulou A, Poulaki I. Rising Like a Phoenix: A Bibliometric and Content Analysis of the Regeneration Concept in Business Studies. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(8):316. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15080316

Chicago/Turabian StyleGlaveli, Niki, Victoria Voulgari, Anastasia Daskalopoulou, and Ioulia Poulaki. 2025. "Rising Like a Phoenix: A Bibliometric and Content Analysis of the Regeneration Concept in Business Studies" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 8: 316. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15080316

APA StyleGlaveli, N., Voulgari, V., Daskalopoulou, A., & Poulaki, I. (2025). Rising Like a Phoenix: A Bibliometric and Content Analysis of the Regeneration Concept in Business Studies. Administrative Sciences, 15(8), 316. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15080316