Abstract

Workplace toxicity in the tourism sector remains a widespread issue, particularly for hotel staff who are constantly suffering from verbal, emotional, or physical abuse. While previous research has primarily highlighted the negative consequences of abusive behavior, this study examines a different perspective—how abusive supervision may be associated with reduced helping behavior among hotel employees, with emotional contagion and self-esteem serving as key moderating and mediating variables. Based on the Conservation of Resources (COR) theory, the current paper suggests that abusive supervision causes people’s psychological resources to be depleted, which decreases their self-esteem and, in turn, their helpful behavior. Furthermore, it is revealed that emotional contagion can act as a moderator to amplify the detrimental association between abusive supervision and self-esteem. Data were gathered from frontline hotels employees. Employing structural equation modeling with SmartPLS 3, the findings reveal that abusive supervision was negatively related to both self-esteem and helping behaviors. Additionally, the correlation between helpful behavior and abusive supervision was strongly mediated by self-esteem. It is also shown that emotional contagion mitigated the detrimental relationship between abusive supervision and self-esteem, such that people with high emotional contagion experienced a stronger negative relationship. This paper advances our theoretical knowledge of workplace dynamics by expanding COR theory to justify how and why abusive supervision impairs pro-social behavior. From a practical standpoint, the findings underscore the significance of management behavior and emotional intelligence in service-oriented sectors. Employee self-esteem and cooperative workplace behavior may be preserved by interventions that deplete supervisory abuse and boost emotional resilience.

1. Introduction

Frontline staff members contribute significantly to the customer experience in the hospitality industry as they represent the firm and are vital to the employee–customer interface (Johnson & Park, 2020). Helping behaviors are crucial in the hospitality domain, as they can increase service quality by encouraging employee collaboration (Kang et al., 2020). Additionally, they can improve customer satisfaction and set hotels apart from competitors (Zhu et al., 2024). Prior studies have focused on the factors influencing hotel staff’s helping behaviors (e.g., Dorien et al., 2020; Gonçalves et al., 2023). Among these antecedents, leadership has been found as critical (Pan et al., 2024). Prior research has primarily investigated positive leadership styles, (i.e., coaching and servant leadership) rather than negative styles (Y. Zhang et al., 2024). In the hospitality domain, abusive supervision exists in light of the increasing pressures on enterprises for survival and creativity (Taheri et al., 2024). Abusive supervision is defined as supervisors’ sustained hostile verbal and non-verbal behavior, excluding physical contact (Tepper, 2000). It can foster a fear culture and prevent workers from voicing their thoughts and ideas (Enwereuzor et al., 2024). This is due to the fact that leaders possess the power to assign incentives and sanctions within a company (Sacavém et al., 2019). Abusive supervision has been consistently linked to a reduction in pro-social workplace behaviors, including helping others (Mackey et al., 2021).

Even though a lot of research has shown that abusive supervision is negatively related to employee outcomes, such as decreased helpful actions, little is known about the psychological mechanisms that underlie these impacts (Ahmad & Begum, 2023; Asim et al., 2024). It is specifically necessary to conduct more research on the function of self-esteem as a mediating component in this connection. This study utilized self-esteem as a critical psychological resource because it is a fundamental, internalized sense of self-worth that has a direct relation to how workers view and react to unfavorable work environments, like abusive supervision. According to the Conservation of Resources (COR), employees want to preserve important resources, such as their sense of self-esteem. These resources are put at risk by abusive supervision, which makes workers feel inferior or undeserving (Asim et al., 2024). As employees struggle to maintain a positive self-view in a hostile environment, this interpersonal mistreatment gradually erodes self-esteem. Thus, abusive supervision is viewed by COR theory as a persistent stressor that depletes psychological resources, with a major victim being self-esteem (Raza, 2023). Self-esteem, in contrast to external resources like social support or organizational resources, is an innate quality that molds people’s coping strategies and resilience from inside, allowing them to continue helpful interpersonal actions in the face of stress (Aslan, 2024). While other resources, like social networks or job control, may lessen workplace toxicity on the outside, self-esteem serves as an internal psychological strength reserve that keeps people motivated and acting in a pro-social manner (S. Lu et al., 2023). In order to better grasp how workers’ fundamental self-evaluations might mitigate the detrimental effects of abusive supervision on helpful behavior, particularly in high-pressure hospitality situations where interpersonal contacts are frequent.

When employees face abusive supervision, they frequently believe that the organization is unconcerned about their well-being, which reduces their intrinsic drive—a critical psychological resource required to alleviate the stressor (Raza, 2023). Hence, abusive supervision is expected to be associated with helping behaviors both directly and indirectly. Directly, abusive supervision may be linked to the depletion of employees’ resources, prompting them to preserve their remaining resources by reducing helping behaviors. Indirectly, abusive supervision may be related to lower self-esteem, which in turn is associated with reduced helping behaviors.

Overall, decreasing helping behaviors is harmful to organizations. In order to cope with abusive supervision to prevent its negative effect on helping behaviors and self-esteem, the COR theory proposes that employees should take measures to replenish with additional resources in order to compensate for the loss of resources caused by abusive supervision (Feng & Wang, 2019). Abusive supervision undermines employees’ sense of value and social worth, endangering their psychological resources, especially their self-esteem (Y. Zhang et al., 2022). Through its impact on the degree to which people absorb the supervisor’s negative feelings, emotional contagion moderates this relationship. Emotionally contagion-prone workers are more likely to internalize and reflect the animosity of their abusive managers, personalizing the abuse and feeling even more devalued (Y. Yu et al., 2022). Since the abuse is absorbed emotionally as well as cognitively, this emotional absorption exacerbates the loss of self-esteem. On the other hand, workers with low emotional contagion are more emotionally aloof and have more psychological resilience (Shi et al., 2025). Because emotional contagion speeds up the process of emotional depletion, it exacerbates the negative impact of abusive monitoring on self-esteem.

Although the negative consequences of abusive supervision have been well-documented by prior research (Labrague, 2024a; Santos et al., 2023), individual-level psychological resources that may mitigate its effects have received less attention (Khan et al., 2022; Laulié et al., 2025). Little-studied factors in this setting include self-esteem (Ahmad & Begum, 2023; Mathieu & Babiak, 2016). As a rather steady internal resource, self-esteem may shield workers from internalizing the damaging signals sent by abusive managers.

Generating more resources to alleviate abusive supervision, prior studies sought to propose techniques for avoiding the negative repercussions of abusive supervision using conscientiousness (Mawritz et al., 2023), organizational support and political skills (Charoensukmongkol, 2024; Li et al., 2016), and agreeableness (Marchant-Pérez et al., 2024; Srikanth, 2019). Despite this, prior research has shown the need to take into account employees’ emotions when dealing with abusive supervision (Chi & Liang, 2013; Elshaer et al., 2025a; Krishna et al., 2023; Malik et al., 2023; X. B. Wang et al., 2023). To the authors’ knowledge, previous research in the hospitality context has ignored the role of emotions in overcoming abusive supervision. This limits hotels’ ability to handle abusive supervision, increasing their negative influence over the targeted individuals. To address this gap, the current study utilizes emotions to mitigate the effects of abusive supervision. As a result, the current study investigates the role of emotional contagion as an emotional resource for mitigating the harmful impact of abusive supervision on self-esteem. Emotional contagion is the transfer of one person’s feelings to another; people with high emotional contagion share the emotions of others and react emotionally to their experiences (Prochazkova & Kret, 2017). Consequently, the association between abusive supervision and self-esteem may be moderated by individual variations in emotional contagion. The detrimental emotional environment that abusive supervision creates may be more likely to affect workers with strong emotional contagion, which might exacerbate the drop in self-esteem and ensuing helpful actions.

This study, which is based on the Conservation of Resources (COR) theory, suggests that emotional contagion and self-esteem are important personal resources that might protect workers from the resource-draining consequences of abusive supervision. The study intends to advance theoretical knowledge of workplace toxicity and pinpoint useful strategies for maintaining pro-social behavior, even under challenging circumstances, by investigating how these factors serve as psychological buffers.

Overall, the study aims are threefold: to examine the direct association between abusive supervision and subordinates helping behaviors, to examine the association between abusive supervision and subordinate self-esteem, and finally to test the moderating role of emotional contagion between abusive supervision and self-esteem.

The current study is predicted to contribute theoretically and practically. This study is expected to advance COR theory by emphasizing self-esteem as a crucial internal resource mediating the relationship between abusive supervision and helpful actions. Additionally, it presents emotional contagion as a moderator, demonstrating how an individual’s emotional sensitivity influences the degree of resource loss. The study also casts doubt on the idea that abuse invariably results in withdrawal, arguing that abused workers may nevertheless act helpfully in some situations (such as when they have a shared emotional experience or perceived resemblance). By doing this, COR theory is extended to consider relational and emotional dynamics, particularly in high-emotion service situations like hospitality.

Practically, this study can assist firms in identifying the hidden costs of abusive supervision on pro-social behavior and collaboration, particularly in the hospitality industry. In order to safeguard psychological resources and foster a positive work environment, managers may create focused interventions—such as coaching, emotional resilience training, and leadership development. Human resource management activities can be employed to lessen the effect of abusive supervision, by choosing emotionally resilient workers, educating leaders on polite conduct, boosting employee self-esteem, and encouraging peer support. Maintaining helpful behaviors and safeguarding employee well-being may be achieved by incorporating these principles into HR tasks, including hiring, training, and employee relations. Additionally, the design of employee development programs, such as self-esteem enhancement workshops, emotional regulation training, and early detection mechanisms for abusive behavior, may be helpful. Ultimately, this can foster a supportive work environment, preserve employee well-being, and maintain service quality and teamwork, which are critical to the success of hospitality organizations.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. The Conservation of Resources (COR) Theory

Conservation of Resources (COR) can be used to examine the motivations behind employees’ actions, including assisting co-workers. Two categories of elements make up the working environment: demands and resources. Resources are organizational, psychological, and social elements that encourage goal achievement and lessen demands. Demands are psychological or physical stressors connected to the process of health impairment. According to (Azazz et al., 2024; Bakker & Demerouti, 2017), an uneven allocation of demands and resources results in a stress that causes undesirable behaviors. Considering this theory, abusive supervision may be deemed as a source of stress.

According to the COR hypothesis, employees will attempt to conserve and minimize resource loss (conservation) or acquire resources required for their routines and obligations when confronted with stressors. Abusive supervision is a stressor over which employees have limited influence. According to this hypothesis, when employees are placed in stressful situations that could result in the loss of personal resources such as energy, cognitive, and emotional resources, they become motivated to save their remaining resources (Hobfoll et al., 2018). As a result, in conditions like abusive supervision, employees will lose vital resources like self-esteem, prompting them to engage in less co-worker support to conserve their remaining resources and prevent further resource depletion. Abusive supervision has been linked to a range of negative outcomes, including work-related attitudes, resistance, deviant behavior, performance, psychological and physical health, and family well-being (Babu et al., 2024; Khairy et al., 2025a; Labrague, 2024b; Malik et al., 2023). From the perspective of subordinates, abusive supervision is a source of stress. Without appropriate solutions, it can lead to various negative effects, including greater turnover (Dhali et al., 2023) and reduced altruistic behavior among employees in the workplace (Asim et al., 2024). In addition to lowering co-workers’ support (Xu et al., 2018).

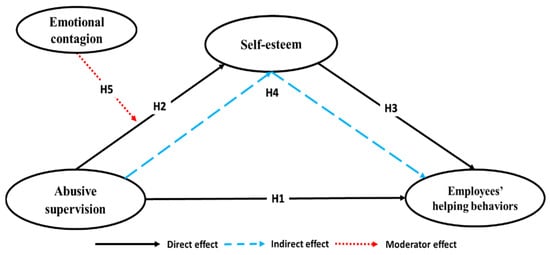

However, the COR hypothesis predicts that persons with higher valuable resource reserves are better equipped to deal with stressors such as abusive supervision and are less likely to enter loss spirals (Hobfoll et al., 2018). This conceptual element contributes to understanding the moderating role of emotional contagion in the research model, as shown in Figure 1. Emotional contagion is the spread of emotions from one person to another. According to (Prochazkova & Kret, 2017), people with strong emotional contagion share other people’s emotions and react emotionally to them. According to (D. Lu & Hong, 2022), emotional contagion is considered a human vulnerability, and people who are easily aroused have a harder time emotionally dealing with stressful experiences. According to prior research, when employees feel unpleasant emotions, emotional contagion can trigger stress and negative outcomes (Jasim et al., 2024; Petitta et al., 2021). However, positive emotional contagion is associated with employee well-being (Xerri et al., 2023). As a result, emotional contagion is expected to modulate the association between abusive supervision and self-esteem, with high emotional contagion dampening the effect of abusive supervision on self-esteem and low emotional contagion buffering the negative association between emotional contagion and self-esteem.

Figure 1.

The research model.

2.2. The Interplay Among Abusive Supervision, Helping Behaviors, and Self-Esteem

Abusive supervision has taken a lot of attention owing to its negative impact on subordinates. As employees rely on their supervisors for assessment, advice, and rewards, hence victims of supervisory abuse may anticipate long-term negative repercussions (Schilpzand et al., 2016).

Helping behaviors are broadly defined as “employees’ willingness and expression of the same to help one another, such as being empathetic, caring, friendly, appreciative, respectful, supportive, and willing to collaborate and carry out work-related tasks” (Attiq et al., 2017). Helping behaviors are a vital resource that help employees develop psychological strength and competence, facilitate frequent social encounters with co-workers, and create a good attitude toward work (Fouad et al., 2025; Qasim et al., 2022). Workers in a coworker-supportive workplace environment assist one another, resulting in a sense of loyalty and belonging that develops affective commitment (Dutta & Rangnekar, 2024). Supportive co-workers have an essential role in influencing the work environment and improving employees’ views of accessible social resources (Gordon et al., 2019). According to (Tsarenko et al., 2018), perceived co-worker support is an essential social resource in the workplace. It serves as a source of compassion in organizations, mitigating emotions of inequity and unfairness (Gordon et al., 2019).

In relation to resources, self-esteem has also been regarded as one of the most essential personal resources in the workplace (Bai et al., 2021). It relates to an individual’s overall perception of his or her value or worth. It denotes an employee’s sense of value as a member of the organization (Ahmed et al., 2021). It also helps to buffer negative workplace experiences, such as bullying and ostracism, and fosters positive outcomes like creativity and engagement (H. Zhang & Jiang, 2022).

Using the COR theory, we argue that abusive supervision can impede hospitality staff’s helpful behaviors. According to COR theory, people will strive to defend their limited resources when they are subjected to a real or threatening loss of resources (Hobfoll et al., 2018). Abusive supervision, which includes rudeness, intimidation, and public criticism, can be a negative workplace stressor (Tepper, 2007). This can lead to feelings of humiliation and drain employees’ self-esteem and self-efficacy. Furthermore, leadership support is an important job resource for employees’ self-development, which can encourage extra-role behaviors (Agina et al., 2025; Tummers & Bakker, 2021). As a result, abusive supervision may cause a resource loss in terms of less social support (W.-R. Lee et al., 2022). Victims may be hesitant to spend further time, energy, and other resources on discretionary behaviors, such as assisting behavior, in order to prevent further resource loss. Additionally, negative experiences have a greater impact on a person’s self-esteem than positive occurrences. Furthermore, individuals are far more likely to remember bad encounters with their supervisors, and these negative occurrences are remembered with intense emotion (Peng et al., 2019). Consequently, an episode of abusive supervision is most likely one form of negative experience that might produce changes in a person’s self-esteem. In parallel, L. Yu et al. (2018) discovered that a person’s self-image is heavily influenced by how they believe others see them. Inclusion in exchange relationships (e.g., with a supervisor) meets a person’s social or psychological demand for self-esteem and attachment (Bani-Melhem et al., 2021). Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

H1.

Abusive supervision negatively associated with helping behaviors.

H2.

Abusive supervision negatively associated with self-esteem.

Self-esteem measures the extent to which people are accepted and respected by others. People who have been frequently rejected and socially despised have reduced self-esteem (Aslan, 2024). Individuals with poor self-esteem may react negatively to rejection and lack social acceptance due to unpleasant interpersonal experiences and views about their worth (Elshaer et al., 2025c; J. Y. Lee et al., 2023). Such sensitivity to rejection and loss of approval likely means that people with low self-esteem are at a higher risk of decreased well-being following a loss of relationship bonds, such as partnership breakdown.

According to (Gómez-Jorge & Díaz-Garrido, 2024), individuals with high self-esteem see themselves as valuable company members and prioritize their skills for job performance. Individuals with poor self-esteem, on the other hand, are more likely to be influenced by their work settings than their counterparts. Self-esteem is linked to several work-related actions and intents, including performance, organizational citizenship, turnover intentions, and attitudes like job satisfaction, dedication, and involvement (Jiang & Tong, 2024). High self-esteem fosters self-confidence in one’s own abilities, a sense of usefulness, and a belief that the world requires one’s existence. Individuals with strong self-esteem have confidence in their ability to attain their goals (Khairy et al., 2025b; Kumar, 2017).

Guo et al. (2022) discovered that people with a high level of self-esteem have better behavioral flexibility (i.e., the skill to change behavior to a different context) than people with a low level of self-esteem. Low self-esteem can lead to uncertainty, a need for external orientation, and a strong need for approval from superiors. This can make employees more vulnerable to negative stressors like abusive supervision (Santos et al., 2023). In the light of the COR, decreased resources due to external stressors directs employees to reserve their remaining resources to prevent spiral loss. Consequently, if self-esteem as a resource was depleted, employees become more prone to prevent further loss of resources via decreasing helping behaviors. In conclusion, the following can be proposed:

H3.

Self-esteem positively associated with helping behaviors.

H4.

Self-esteem mediates the link between abusive supervision and helping behaviors.

2.3. The Moderating Role of Emotional Contagion

Previous studies have explored the link between abusive supervision and self-esteem (Vogel & Mitchell, 2017). R. Wang et al. (2016), for example, investigated the moderating role of subordinate self-esteem in the link between abusive supervision, and subordinate psychological distress. The idea of ego depletion is particularly important for investigating and answering why and how abusive supervision affects employee behavior, emotions, and job results (Chen et al., 2023).

Despite the COR arguing that abusive supervision depleting personal resources, it also suggests that individuals with more substantial resource reserves are better fortified to overcome the threats of stressors, such as abusive supervision, and are less likely to enter loss spirals (Hobfoll et al., 2018). Consequently, emotional regulation as a way of providing more resources becomes crucial.

Navigating abusive supervision requires significant self-regulation due to individuals’ low self-control capacity (Elshaer et al., 2025d; Saleem et al., 2024). This means that people received abusive supervision should exercise some control over their emotional, behavioral, and cognitive responses in order to cope with the negative consequences of such mistreatment. For instance, an employee may face ongoing verbal harassment and humiliation from their supervisor. In this situation, the individual must self-regulate to reject counterproductive conduct while maintaining a professional manner (Renn et al., 2018). This self-regulation effort may entail repressing emotions and focusing on professional responsibilities in the face of tough conditions.

According to Oggiano (2022), emotions are a collection of endogenous and exogenous inputs to certain brain systems that produce both internal and external expressions. Subjective sentiments and emotions are interpreted intellectually and show up physiologically in different ways.

Emotional contagion theory states that people frequently “catch” other people’s emotions without realizing it. Primitive emotional contagion is described by (Herrando & Constantinides, 2021; Zablah et al., 2017) as the synchronization of two parties’ facial expressions, postures, gestures, and vocalizations. Consequently, the feelings of the two people become more similar. On the one hand, employees’ poor emotion management can lead to emotional contagion, which is a source of stress. Consequently, it might result in unpleasant emotions like rage or worry, which can be detrimental to one’s well-being (Elshaer et al., 2025b; Williams et al., 2024). Conversely, those with low emotional contagion are better able to control their emotions, which increases positive emotions like joy and decreases negative ones like anger, worry, and impatience. In their primary study of general positive and negative association, researchers found that positive effects were negatively correlated with stress, depression, and burnout and positively correlated with job satisfaction and well-being, while negative effect had the opposite effect (e.g., Aboutaleb et al., 2025; Rouxel et al., 2016). Based on these insights, we suggest our initial hypothesis:

H5.

Emotional contagion moderates the correlation between abusive supervision and self-esteem (Employees with high emotional contagion increases the negative correlation between abusive leadership and self-esteem).

3. Methods

3.1. Procedures

This study utilized a quantitative research design to investigate the association between abusive supervision (AS) and employees’ helping behaviors (HB), focusing on the mediating role of self-esteem (SE) and the moderating role of emotional contagion (EC). A thorough literature review was explored to assist in developing the conceptual framework, and a validated scale from previous studies were derived to structure the questionnaire. The designed questionnaire was delivered to the target participants, and the collected data were analyzed using PLS-SEM.

Data were collected through a structured survey questionnaire targeting senior frontline employees working in five-star hotels in Egypt. The hotel sector comprises a wide range of job functions—such as frontline and back-of-house roles—that vary significantly in terms of job complexity (C.-J. Wang et al., 2014). Frontline employees face numerous daily challenges at work, including high physical workloads, limited decision-making authority, and elevated psychological demands. These factors collectively contribute to increased levels of job stress among frontline staff (Salem, 2015). In addition, high-ranking hotels are typically committed to fostering a favorable organizational climate that enhances employee satisfaction, which in turn contributes to improved customer satisfaction. Accordingly, it is assumed that such hotels would be more cooperative with the authors in facilitating the field study. Participation was limited to those with at least two years of experience, ensuring that respondents had the necessary background to provide informed and comprehensive answers to the survey. The research team coordinated with the hotels’ HR managers, providing them with the survey link. The HR managers then communicated the study’s purposes to the staff and distributed the questionnaires following approval from hotel management. Participation in the survey was voluntary, and respondents’ answers were treated with strict confidentiality. Participants were also informed that their consent to participate would be considered as signing the informed consent form. Data were collected in September 2024 using convenience sampling. The study employed a convenience sampling approach due to practical considerations, including time constraints, cost efficiency, and ease of access to respondents. While this method raises concerns regarding the representativeness and generalizability of the findings, it is deemed acceptable when large sample sizes are used (Jager et al., 2017). This limitation has been explicitly acknowledged as a constraint of the current study. To minimize method bias, the questionnaire was translated using the back-translation technique, following the guidelines of (Brislin, 1980). The instrument was also reviewed by a panel of academic and industry experts to ensure the clarity and appropriateness of the items about the study’s objectives. Moreover, the measurement items were randomly ordered to reduce the likelihood of respondents detecting the proposed relationships. Approximately 600 questionnaires were distributed, and 428 responses were collected, yielding a response rate of 62%. All responses were valid, as the feature requiring participants to answer each question before proceeding to the next was enabled. The sample included 306 males (71.5%) and 122 females (28.5%). Most participants (46.5%) ranged from 18 to 29 years old. Table 1 shows the demographic data of the participants.

Table 1.

Respondents’ demographic background.

3.2. Measures

The developed questionnaire was structured into two main sections: the first part gathered demographic data about the selected respondents, while the second had items about the 4 dimensions outlined in the proposed model. All items for the variables were adapted from previous studies and assessed using a 5-point Likert scale. Abusive supervision (AS) was gauged using six items from (Harris et al., 2011). The sample items include the following statement: “My supervisor makes negative comments about me to others”. The helping behaviors (HB) were assessed utilizing 4 items from (Farh et al., 1997). The measure includes items such as the following: “Willing to assist new colleagues to adjust to the work environment.” Ten items for measuring self-esteem variable were borrowed from (Rosenberg, 1965). Sample items included the following: “I feel that I am a person of worth, at least on an equal plane with others.” Finally, the 6-item scale was used to gauge emotional contagion from (Mehrabian & Epstein, 1972). The sample items include the following: “I become nervous if others around me seem to be nervous.” Seventeen academics and hotel executives reviewed the questionnaire to evaluate its clarity, ensure that the terminology used was unambiguous, and confirm the accuracy of the language. Minor linguistic adjustments were made during this process.

3.3. Analysis of the Study Data

The hypotheses were evaluated by employing PLS-SEM and Smart PLS V3.0. PLS-SEM was chosen over CB-SEM as the study focuses on predicting variables rather than validating a theoretical model, thus extending existing structural theory (Hair et al., 2011). This method is particularly suitable for testing complex models with fewer data constraints and varying sample sizes, prioritizing prediction accuracy (Sarstedt et al., 2016). Additionally, PLS is adequate for both exploratory and confirmatory analyses, handling intricate relationships among multiple constructs (Hair et al., 2021).

3.4. Test of Common Method Bias (CMB) and Normality

As per Harman’s single factor suggestions, CMB can exist when the variance of one factor surpass the value of 50%. The results showed that one single dimension explained 36.829%. Consequently, CMB was not a problem (Podsakoff et al., 2003). The skewness and kurtosis scores were also inspected to assess the data’s normality. Absolute skewness and kurtosis values for every variable were found to be lower than the suggested thresholds of 2.1 and 7.1 (Table 2) (Curran et al., 1996), confirming that non-normality was also not a problem.

Table 2.

Scale validity and reliability.

4. The Results

PLS-SEM involves a two-step process: first, the assessment of the measurement (outer) model, which includes evaluating Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability, average variance extracted (AVE), as well as the Fornell–Larcker criterion and the Heterotrait–Monotrait ratio (HTMT). Second, the structural (inner) model is assessed by examining the R2 and Q2 values, along with hypothesis testing based on the path coefficients (β) and t-values (Hair et al., 2017).

4.1. Measurement Model Outcomes

The outer measurement model was assessed regarding convergent (CV) and discriminant (DV) validity. “Cronbach’s alpha”, “factor loading”, and “composite reliability” should be higher than 0.7, and the “Average Variance Extracted” (AVE) should be higher than 0.5 to confirm the validity of the outer model (Hair et al., 2011). Likewise, regarding DV, the √AVE of each dimension should surpass the correlation between that dimension and other dimensions as pictured in the model (Fornell & Larcker, 1981), in addition to the “Heterotrait-Monotriat ratio” of which correlation HTMT should be <0.9 (Gold et al., 2001) to confirm the DV of the model. The results in Table 2 and Table 3 demonstrate that the standards for achieving CV and DV have been fulfilled, thus guaranteeing the outer model validity.

Table 3.

Discriminant validity (DV).

4.2. Inner Model Assessment

As shown in Table 2, VIF’s values were >5, revealing no problem with multicollinearity (Hair et al., 2011). Similarly, according to Table 4, R2 of helping behaviors (R2 = 0.283) and self-esteem (R2 = 0.398) variables were >0.10, and Q2 of these variables were 0.0; thus, the proposed model’s explanatory precision was satisfactory (Hair et al., 2014). The following equation (the result must be greater than 0.36) (Mital et al., 2018; Tenenhaus et al., 2005) and the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) (SRMR should be <0.08) (Hu & Bentler, 1998) have been employed in addition to the previous criteria to assess the proposed model’s Goodness of Fit (GoF).

Table 4.

Hypotheses analysis.

After applying the equation, the GoF was 0.488, and the SRMR value was 0.065, indicating the acceptable GoF.

After investigating and confirming the fitness of the study outer and inner models, the pass coefficients (β), and related t-value, and p-values were evaluated to judge the study hypotheses (Table 4).

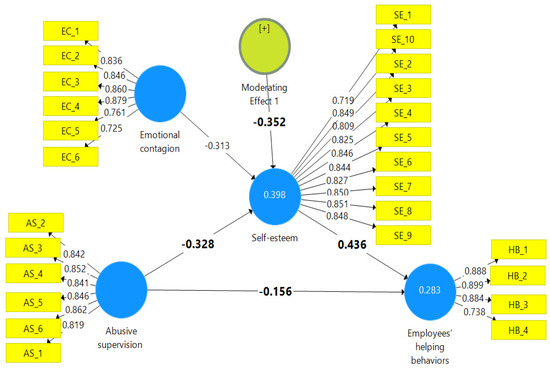

The results of Figure 2 and Table 4 give evidence that abusive supervision is negatively associated with helping behaviors at β = −0.156, t = 3.718, and p < 0.009) and self-esteem (β = −0.328, t = 7.341, p < 0.000), confirming H1 and H2. Furthermore, self-esteem was positively associated with helping behaviors at β = 0.436, t = 8.676, and p < 0.000, ensuring H3. Moreover, the analysis of effect sizes (f2) indicates that the effect size of abusive supervision on helping behaviors was small (f2 = 0.025), while the path from abusive supervision to self-esteem demonstrated a near-moderate effect size (f2 = 0.126). The path from self-esteem to helping behaviors showed a moderate effect size (f2 = 0.198). These values were interpreted following (Cohen, 2013) guidelines. Additionally, self-esteem successfully mediated the effect of abusive supervision on helping behaviors (β = −0.143, t = 5.062, p < 0.000), supporting H4. Additionally, a mediation effect was considered statistically significant when the 95% confidence interval did not include zero (LLCI > 0 or ULCI < 0), as shown in Table 4.

Figure 2.

The study model.

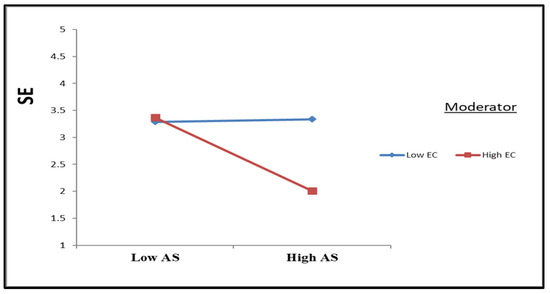

Emotional contagion (EC), according to Table, strengthens the correlation between abusive supervision and self-esteem (β = −0.352, t = 8.717, and p = 0.000), sustaining H5. Furthermore, a simple slope analysis was conducted at ±1 standard deviation of EC. As depicted in Figure 3, under conditions of high EC, the negative association between AS and SE becomes significantly stronger. Specifically, employees with high levels of EC experience a sharper decline in SE as AS increases, compared to those with low EC, for whom the relationship between AS and SE appears negligible.

Figure 3.

The role of EC as moderator in the link between AS → SE.

Multi-Group Analysis Based on Experience

To explore whether variations exist based on employees’ tenure, the study utilized the Multi-Group Analysis (MGA) approach within the SmartPLS framework. Following established MGA guidelines, a hypothesis is deemed significant when the p-value is below 0.05 or the t-value exceeds 1.96 (Cheah et al., 2020). As summarized in Table 5, the analysis revealed no statistically significant discrepancies in the structural relationships across different levels of employee experience. These findings indicate that tenure does not play a significant role in the examined structural model.

Table 5.

Multi-group analysis.

5. Discussion and Theoretical Implication

This study examined the relationship between abusive supervision and employees’ helping behaviors, with a focus on self-esteem as a mediating mechanism and emotional contagion as a moderating factor. We found that abusive supervision significantly related to helping behaviors (β = −0.156, p ≤ 0.001). Our findings, which are supported by the Conservation of Resources (COR) hypothesis (Hobfoll, 1989), demonstrate how abusive supervision imperils important psychological resources and diminishes pro-social and discretionary behaviors. Employees under abusive supervision were less likely to act helpfully, which is in line with previous research suggesting that hostile leadership erodes interpersonal support in companies (i.e., Asim et al., 2024; Zhao & Guo, 2019). Abuse of supervision is a serious resource hazard from the standpoint of COR. According to (Hobfoll et al., 2018), it saps workers’ psychological well-being, emotional vitality, feelings of security, and self-worth. The depletion of resources experienced by workers under abusive supervision is likely to result in feelings of emotional tiredness, disengagement, and burnout. According to COR theory, people will adopt resource conservation measures when they encounter resource loss. In order to save their remaining psychological and emotional resources, employees may stop engaging in helpful actions as a self-defense tactic. This is particularly likely in abusive environments, where helping may not only go unappreciated but may also expose employees to further mistreatment.

One of the key contributions of this study is the identification of self-esteem as a psychological mechanism linking abusive supervision to reduced helping behavior (β = −0.143, p ≤ 0.001). The degree to which people believe they are competent and valued members of an organization is known as self-esteem (Aslan, 2024). According to the COR approach, self-esteem is a personal resource that allows people to perform well and sustain healthy social relationships. People are driven to acquire, preserve, and safeguard their valuable resources. The results indicated that employees’ self-esteem appears to be undermined by supervisor maltreatment (β = −0.328, p ≤ 0.001), which lowers their motivation and capacity to support colleagues. When self-esteem is compromised such as through abusive supervision, lack of recognition, or social exclusion, it signals a resource loss, triggering psychological distress and defensive behaviors aimed at resource preservation in form of decreasing helping behavior. In order to prevent further depletion of resources, employees may stop from helpful acts when their self-esteem is damaged by abusive supervision (β = 0.436, p ≤ 0.001). According to Y. Zhang et al. (2024), employees who have poor self-esteem may not have the confidence or drive to help others since helping others demands a certain level of emotional resilience and self-assurance. Furthermore, helpful actions are frequently not publicly recognized, which makes them less likely to be given priority when someone’s identity is in jeopardy. Recent studies have supported this mechanism. (W.-R. Lee et al., 2022), for instance, discovered that the association between abusive supervision and a decrease in proactive actions, such as assisting, was strongly mediated by self-esteem. According to (Wu et al., 2023), social disengagement and a decline in extra-role actions were also associated with low self-esteem brought on by abusive supervision.

The detrimental relationship between abusive supervision and self-esteem was more pronounced for workers with high emotional contagion, who have a propensity to internalize and absorb the emotional states of others. According to (Schmidt et al., 2024), emotionally sensitive people are particularly susceptible to the emotional toll of toxic leadership, which intensifies their depletion of resources and, eventually, diminishes their ability to act in a helpful manner. On the other hand, those who have low emotional contagion could be more able to withstand abuse, retaining their sense of self-worth and engaging in some pro-social activities (β = −0.352, p ≤ 0.001). This may be explained by the COR hypothesis, which also contends that people who have larger stores of resources are less prone to experience loss spirals and are better able to withstand the dangers of stresses like abusive supervision. A resource caravan is a key extension of COR theory, which suggests that resources tend to cluster and travel together (Hobfoll et al., 2018). People with certain resources are more likely to accumulate additional resources, while those lacking them are more prone to further loss. According to this perspective, emotional resources like optimism, social support, emotional intelligence, and resilience move in caravans and reinforce one another to create more robust psychological defenses. Even under toxic leadership, a robust resource caravan can serve as a buffer, halting the complete breakdown of self-esteem.

Theoretically, our findings demonstrate the critical role that individual differences in emotional sensitivity—in particular, emotional contagion—play in influencing how workers perceive and react to abusive supervision within the context of Conservation of Resources (COR) theory. The degree to which people internalize negative emotional cues from their supervisors is related to emotional contagion, which in turn is associated with the rate and severity of resource depletion, particularly with regard to self-esteem. Workers with high emotional contagion are more prone to take in negative feelings, which can cause more serious psychological damage and a quicker decline in self-esteem. This supports COR’s claim that internal vulnerabilities, as well as external stresses, contribute to resource loss, highlighting the fact that emotional sensitivity can increase susceptibility to interpersonal hazards and accelerate the depletion of vital psychological resources.

Regarding the potential relationship between organizational tenure and the proposed relationships, the results indicated that tenure did not exert any statistically significant influence on any of the structural paths examined. Previous research suggests that the length of time an individual has spent within an organization may significantly influence how they interpret and respond to both favorable and unfavorable workplace conditions (Chan & Mak, 2014). Employees with longer organizational tenure tend to expect fair and appropriate treatment from their organization or supervisors, given the considerable time and effort they have invested over the course of their careers. They also typically possess greater autonomy and authority than newcomers or less-experienced employees. Therefore, the negative effects of abusive supervision are likely to be more salient among long-tenured employees, as such behavior directly contradicts the expectations they have built over time (Kim et al., 2018). The absence of significant differences in the proposed relationships across tenure groups in this study may be explained by the growing unacceptability of abusive supervision in the hotel work environment. This shift can be attributed to the rising awareness among younger generations—particularly Generation Z—regarding the importance of employee well-being and a supportive organizational climate.

6. Practical Implication

The empirical findings of this study confirmed the well-established nature of work in the hospitality sector, which demands intensive emotional and physical effort. Accordingly, this study offers a set of recommendations for hotel management to address the dynamics of interpersonal relationships within hotel operations to sustain service distinction and ensure employee well-being.

Firstly, with the approval of the first and second hypotheses and the confirmation of the negative association between abusive supervision and both helping behaviors (H1) and employees’ self-esteem (H2), there is an urgent need for hotel management to implement leadership development strategies that actively prevent such harmful behaviors. Hotels should design formal training programs for supervisors and managers that emphasize emotional intelligence, ethical conduct, and respect-based communication in daily interactions. These programs should aim to foster a supportive and psychologically safe work environment. Additionally, incorporating anonymous employee satisfaction surveys can serve as an early detection mechanism, allowing management to identify and address abusive supervision patterns before they escalate or cause long-term damage to employee morale and organizational performance.

Secondly, the result of the third hypothesis, which confirms the positive association between self-esteem and helping behaviors (H3), indicates that investing in the psychological capital of hotel employees can lead to a more positive collaborative work environment. Therefore, organizational support should be provided to enhance employees’ sense of self-esteem, fostering a culture of teamwork and reciprocal helping behaviors.

Thirdly, the mediating role (indirect relationship) in the relationship between abusive supervision and helping behaviors (H4) highlights the significance of self-confidence and emotional stability among hospitality employees. Therefore, training programs, personal development workshops, and mental health support initiatives should be developed to empower employees and help them cultivate greater self-esteem. It is also vital to boost psychologically safe work environments where employees feel respected and supported.

Finally, emotional contagion was found to moderately strengthen the negative association between abusive supervision and employees’ self-esteem (H5). This emphasizes that emotionally sensitive employees, who are more susceptible to emotional contagion, are at greater risk of being impacted by toxic leadership, potentially leading to diminished employee self-esteem. In this regard, such employees should be trained in workplace resilience, and counselling services or wellness resources should be made available to help them cope with work-related stress.

7. Limitations and Future Research

While this research paper offers some valuable insights about how abused hotel employees can help peers through emotional contagion and self-esteem, some limitations can be acknowledged. First, our paper employed a self-reported data collection method, that may cause bias, principally considering the sensitive environment of workplace abuse future studies might use multiple sources of data to avoid this type of bias. Second, the research mainly focuses on a specific context (hotel employees), which may restrict the generalizability of the study results to another context. Cross-industry comparisons could be suggested to validate the current study results. Third, the paper utilized a cross-sectional approach, limiting causal inferences. A longitudinal design would be preferred in future studies to better understand the proposed relationships. Finally, we employed emotional contagion and self-esteem as mediators and moderators. Other factors (e.g., organizational commitment and leadership style) may also play a key role but were not examined in our study. Future research can investigate these additional factors to offer a more comprehensive understanding of the evaluated model.

8. Conclusions

This study underscores the harmful relationship between abusive supervision and employees’ helping behaviors and self-esteem, as well as the moderating role of emotional contagion. By analyzing 428 questionnaires from senior frontline employees working in five-star hotels in Egypt, the results indicated that abusive leadership diminishes self-esteem and reduces helping behaviors, with self-esteem playing a partial mediating role. Moreover, the findings highlight the relevance of individual emotional sensitivity, indicating that employees with high levels of emotional contagion tend to report stronger associations with supervisory abuse. Furthermore, Multi-Group Analysis (MGA) was conducted using SmartPLS, which indicated that tenure was not significantly related to the proposed associations. This implies that the observed links between abusive supervision and the study variables were consistent across different experience levels, affecting all exposed employees in a similar manner. Overall, the study enhances the understanding of the psychological mechanisms and contextual factors associated with employee responses to negative leadership, providing valuable implications for both theory and practice in organizational behavior.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.A.E., O.E. and S.F.; methodology, I.A.E., S.F., O.E. and A.M.S.A.; software, I.A.E. and S.F.; validation, I.A.E., A.M.S.A. and S.F.; formal analysis, I.A.E., O.E., and A.M.S.A.; investigation, I.A.E., S.F., O.E. and A.M.S.A.; resources, I.A.E.; data curation, I.A.E.; writing—original draft preparation, S.F., I.A.E. and A.M.S.A.; writing—review and editing, I.A.E., S.F., O.E. and A.M.S.A.; visualization, I.A.E.; supervision, I.A.E.; project administration, I.A.E., S.F. and A.M.S.A.; funding acquisition, I.A.E. and A.M.S.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research, Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia [Project No. KFU251695].

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the deanship of the scientific research Ethical Committee, King Faisal University (protocol code KFU-251695 and 25th July of 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Aboutaleb, M., Mohammad, A., & Fayyad, S. (2025). Emotional contagion in hotels: How psychological resilience shapes employees’ performance, satisfaction, and retention. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism. Ahead of print. 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agina, M. F., Farrag, D. A., Jaber, H. M., Fayyad, S., Abbas, T. M., Salameh, A. A., & ELziny, M. N. (2025). The influence of customer incivility on hotel frontline employees’ responses and service sabotage: Does co-worker support matter? GeoJournal of Tourism and Geosites, 58(1), 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I., & Begum, K. (2023). Impact of abusive supervision on intention to leave: A moderated mediation model of organizational-based self esteem and emotional exhaustion. Asian Business & Management, 22(2), 669–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, O., Nayeem Siddiqua, S. J., Alam, N., & Griffiths, M. D. (2021). The mediating role of problematic social media use in the relationship between social avoidance/distress and self-esteem. Technology in Society, 64, 101485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asim, M., Liu, Z., Ghani, U., Nadeem, M. A., & Yi, X. (2024). Abusive supervision and helping behavior among nursing staff: A moderated mediation model. Journal of Health Organization and Management, 38(5), 724–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslan, Y. (2024). The mediating role of self-esteem in the relationship between perceived family social support and life satisfaction: A study on youth. Journal of Social Service Research, 50(5), 847–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attiq, S., Wahid, S., Javaid, N., Kanwal, M., & Shah, H. J. (2017). The impact of employees’ core self-evaluation personality trait, management support, co-worker support on job satisfaction, and innovative work behaviour. Pakistan Journal of Psychological Research, 32(1), 247–271. [Google Scholar]

- Azazz, A. M. S., Elshaer, I. A., Alyahya, M., Abdulaziz, T. A., Elwardany, W. M., & Fayyad, S. (2024). Amplifying unheard voices or fueling conflict? Exploring the impact of leader narcissism and workplace bullying in the tourism industry. Administrative Sciences, 14(12), 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, N., De Roeck, K., Rivkin, W., & Bhattacharya, S. (2024). I can do good even when my supervisor is bad: Abusive supervision and employee socially responsible behaviour. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 97(2), 555–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X., Jiang, L., Zhang, Q., Wu, T., Wang, S., Zeng, X., Li, Y., Zhang, L., Li, J., Zhao, Y., & Dai, J. (2021). Subjective family socioeconomic status and peer relationships: Mediating roles of self-esteem and perceived stress. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 634976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2017). Job demands–resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bani-Melhem, S., Quratulain, S., & Al-Hawari, M. A. (2021). Does employee resilience exacerbate the effects of abusive supervision? A study of frontline employees’ self-esteem, turnover intention, and innovative behaviors. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 30(5), 611–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R. W. (1980). Translation and content analysis of oral and written materials. Methodology, 2, 389–444. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, S. C. H., & Mak, W. (2014). The impact of servant leadership and subordinates’ organizational tenure on trust in leader and attitudes. Personnel Review, 43(2), 272–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charoensukmongkol, P. (2024). The interaction of organizational politics and political skill on employees’ exposure to workplace cyberbullying: The conservation of resources theory perspective. Asia-Pacific Journal of Business Administration, 16(4), 940–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheah, J.-H., Thurasamy, R., Memon, M. A., Chuah, F., & Ting, H. (2020). Multigroup analysis using SmartPLS: Step-by-step guidelines for business research. Asian Journal of Business Research, 10(3), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., Wang, Y., Cooke, F. L., Lin, L., Paillé, P., & Boiral, O. (2023). Is abusive supervision harmful to organizational environmental performance? Evidence from China. Asian Business & Management, 22(2), 689–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, S.-C. S., & Liang, S.-G. (2013). When do subordinates’ emotion-regulation strategies matter? Abusive supervision, subordinates’ emotional exhaustion, and work withdrawal. The Leadership Quarterly, 24(1), 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (2013). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Curran, P. J., West, S. G., & Finch, J. F. (1996). The robustness of test statistics to nonnormality and specification error in confirmatory factor analysis. Psychological Methods, 1(1), 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhali, K., Al Masud, A., Hossain, M. A., Lipy, N. S., & Chaity, N. S. (2023). The effects of abusive supervision on the behaviors of employees in an organization. Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 8(1), 100695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorien, O., Avau, B., De Buck, E., Issard, D., Vandekerckhove, P., & Cassan, P. (2020). Factors associated with helping behavior when witnessing an accident: A cross-sectional survey. International Journal of First Aid Education, 3(2), 42–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, A., & Rangnekar, S. (2024). Co-worker support for human resource flexibility and resilience: A literature review (pp. 93–109). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaer, I. A., Azazz, A. M. S., Aljoghaiman, A., Fayyad, S., Abdulaziz, T. A., & Emam, A. (2025a). The lighter side of leadership: Exploring the role of humor in balancing work and family demands in tourism and hospitality. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(2), 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaer, I. A., Azazz, A. M. S., Alyahya, M., Mohammad, A. A. A., Fayyad, S., & Elsawy, O. (2025b). Emotional contagion in the hospitality industry: Unraveling its impacts and mitigation strategies through a moderated mediated PLS-SEM approach. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(1), 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaer, I. A., Azazz, A. M. S., Kooli, C., Aljoghaiman, A., Elsawy, O., & Fayyad, S. (2025c). Green transformational leadership’s impact on employee retention: Does job satisfaction and green support bridge the gap? Administrative Sciences, 15(5), 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaer, I. A., Azazz, A. M. S., Zain, M. E. A., Fayyad, S., ElShaaer, N. I., & Mahmoud, S. W. (2025d). The dark side of the hospitality industry: Workplace bullying and employee well-being with feedback avoidance as a mediator and psychological safety as a moderator. Healthcare, 13(3), 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enwereuzor, I. K., Onyishi, A. B., & Ekwesaranna, F. (2024). Climate of fear and job apathy as fallout of supervisory nonphysical hostility toward casual workers in the banking industry. Journal of Organizational Effectiveness: People and Performance, 11(4), 788–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farh, J.-L., Earley, P. C., & Lin, S.-C. (1997). Impetus for action: A cultural analysis of justice and organizational citizenship behavior in Chinese society. Administrative Science Quarterly, 42(3), 421–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J., & Wang, C. (2019). Does abusive supervision always promote employees to hide knowledge? From both reactance and COR perspectives. Journal of Knowledge Management, 23(7), 1455–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(3), 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouad, A. M., Abdullah Khreis, S. H., Fayyad, S., & Fathy, E. A. (2025). The dynamics of coworker envy in the green innovation landscape: Mediating and moderating effects on employee environmental commitment and non-green behavior in the hospitality industry. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, A. H., Malhotra, A., & Segars, A. H. (2001). Knowledge management: An organizational capabilities perspective. Journal of Management Information Systems, 18(1), 185–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, T., Curado, C., & Martsenyuk, N. (2023). When do we share knowledge? A mixed-methods study of helping behaviors and HR management practices. Business Process Management Journal, 29(2), 369–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, S., Adler, H., Day, J., & Sydnor, S. (2019). Perceived supervisor support: A study of select-service hotel employees. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 38, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Jorge, F., & Díaz-Garrido, E. (2024). Managing employee self-esteem in higher education: Impact on individuals, organizations and society. Management Decision, 62(10), 3063–3084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J., Huang, X., Zheng, A., Chen, W., Lei, Z., Tang, C., Chen, H., Ma, H., & Li, X. (2022). The influence of self-esteem and psychological flexibility on medical college students’ mental health: A cross-sectional study. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 836956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2014). A primer on partial least squares (PLS) structural equation modeling. SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., Danks, N. P., & Ray, S. (2021). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) using R: A workbook. Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 19(2), 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, K. J., Harvey, P., & Kacmar, K. M. (2011). Abusive supervisory reactions to coworker relationship conflict. The Leadership Quarterly, 22(5), 1010–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrando, C., & Constantinides, E. (2021). Emotional contagion: A brief overview and future directions. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 712606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobfoll, S. E., Halbesleben, J., Neveu, J.-P., & Westman, M. (2018). Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5(1), 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1998). Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods, 3(4), 424–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jager, J., Putnick, D. L., & Bornstein, M. H. (2017). II. More than just convenient: The scientific merits of homogeneous convenience samples. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 82(2), 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jasim, T. A., Moneim, A. A., EL-sayed, S. F., Khairy, H. A., & Fayyed, S. (2024). Understanding the nexus between abusive supervision, knowledge hiding behavior, work disengagement, and perceived organizational support in tourism and hospitality industry. GeoJournal of Tourism and Geosites, 55(3), 1039–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X., & Tong, Y. (2024). Psychological capital and music performance anxiety: The mediating role of self-esteem and flow experience. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1461235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K. R., & Park, S. (2020). Mindfulness training for tourism and hospitality frontline employees. Industrial and Commercial Training, 52(4), 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H. J. A., Kim, W. G., Choi, H.-M., & Li, Y. (2020). How to fuel employees’ prosocial behavior in the hotel service encounter. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 84, 102333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khairy, H. A., Agina, M. F., Ahmad, M. S., & Fayyad, S. (2025a). Distributive injustice effect on employee’s innovative behavior in hotels: Roles of workplace envy and workplace spirituality. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality & Tourism, 24(3), 561–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khairy, H. A., Fayyad, S., & El Sawy, O. (2025b). AI awareness and work withdrawal in hotel enterprises: Unpacking the roles of psychological contract breach, job crafting, and resilience. Current Issues in Tourism. Ahead of print. 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S., Kiazad, K., Sendjaya, S., & Cooper, B. (2022). A multilevel model of abusive supervision climate. Personnel Review, 51(9), 2347–2370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. L., Son, S. Y., & Yun, S. (2018). Abusive supervision and knowledge sharing: The moderating role of organizational tenure. Personnel Review, 47(1), 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, S. H., Prasad, K. D. V., Rajasekhar, M., Ashokkumar, N., & Vatsa, G. (2023). Perceived mental stress of faculties and their methods of coping with special reference to private universities. Journal for ReAttach Therapy and Developmental Diversities, 6(4s), 349–358. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, N. (2017). Self-esteem and its impact on performance. Indian Journal of Positive Psychology, 8(2), 142. [Google Scholar]

- Labrague, L. J. (2024a). Abusive supervision and its relationship with nursing workforce and patient safety outcomes: A systematic review. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 46(1), 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrague, L. J. (2024b). Stress as a mediator between abusive supervision and clinical nurses’ work outcomes. International Nursing Review, 71(4), 997–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laulié, L., Tekleab, A. G., & Rousseau, D. M. (2025). Psychological contracts at different levels: The cross-level and comparative multilevel effects of team psychological contract fulfillment. Group & Organization Management, 50(3), 1020–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. Y., Patel, M., & Scior, K. (2023). Self-esteem and its relationship with depression and anxiety in adults with intellectual disabilities: A systematic literature review. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 67(6), 499–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, W.-R., Kang, S.-W., & Choi, S. B. (2022). Abusive supervision and employee’s creative performance: A serial mediation model of relational conflict and employee Silence. Behavioral Sciences, 12(5), 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X., Qian, J., Han, Z. R., & Jin, Z. (2016). Coping with abusive supervision: The neutralizing effects of perceived organizational support and political skill on employees’ burnout. Current Psychology, 35(1), 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D., & Hong, D. (2022). Emotional contagion: research on the influencing factors of social media users’ negative emotional communication during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 931835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S., Wang, L., Ni, D., Shapiro, D. L., & Zheng, X. (2023). Mitigating the harms of abusive supervision on employee thriving: The buffering effects of employees’ social-network centrality. Human Relations, 76(9), 1441–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackey, J. D., McAllister, C. P., & Alexander, K. C. (2021). Insubordination: Validation of a measure and an examination of insubordinate responses to unethical supervisory treatment. Journal of Business Ethics, 168(4), 755–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, O. F., Jawad, N., Shahzad, A., & Waheed, A. (2023). Longitudinal relations between abusive supervision, subordinates’ emotional exhaustion, and job neglect among Pakistani Nurses: The moderating role of self-compassion. Current Psychology, 42(31), 26945–26965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchant-Pérez, P., Leitão, J., & Nunes, A. (2024). Abusive leadership: A systematic review of the literature (pp. 423–455). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, C., & Babiak, P. (2016). Corporate psychopathy and abusive supervision: Their influence on employees’ job satisfaction and turnover intentions. Personality and Individual Differences, 91, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawritz, M. B., Ambrose, M. L., & Priesemuth, M. (2023). Toxic triads: Supervisor characteristics, subordinate self-esteem, and supervisor stressors in relation to perceptions of abusive supervision. Human Performance, 36(4), 180–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A., & Epstein, N. (1972). A measure of emotional empathy1. Journal of Personality, 40(4), 525–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mital, M., Chang, V., Choudhary, P., Papa, A., & Pani, A. K. (2018). Adoption of Internet of Things in India: A test of competing models using a structured equation modeling approach. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 136, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oggiano, M. (2022). Neurophysiology of emotions. In Neurophysiology—Networks, plasticity, pathophysiology and behavior. IntechOpen. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L., Kao, K.-Y., Hsu, H.-H., Thomas, C. L., & Cobb, H. R. (2024). Linking job autonomy to helping behavior: A moderated mediation model of transformational leadership and mindfulness. Current Psychology, 43(21), 19370–19385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, A. C., M. Schaubroeck, J., Chong, S., & Li, Y. (2019). Discrete emotions linking abusive supervision to employee intention and behavior. Personnel Psychology, 72(3), 393–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petitta, L., Probst, T. M., Ghezzi, V., & Barbaranelli, C. (2021). Emotional contagion as a trigger for moral disengagement: Their effects on workplace injuries. Safety Science, 140, 105317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prochazkova, E., & Kret, M. E. (2017). Connecting minds and sharing emotions through mimicry: A neurocognitive model of emotional contagion. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 80, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasim, S., Usman, M., Ghani, U., & Khan, K. (2022). Inclusive leadership and employees’ helping behaviors: Role of psychological factors. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 888094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raza, S. A. (2023). The impact of burnout on the psychological well-being of ESL students in higher education environment. Siazga Research Journal, 2(3), 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renn, R. W., Steinbauer, R., & Biggane, J. (2018). Reconceptualizing self-defeating work behavior for management research. Human Resource Management Review, 28(2), 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton University Press. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt183pjjh (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- Rouxel, G., Michinov, E., & Dodeler, V. (2016). The influence of work characteristics, emotional display rules and affectivity on burnout and job satisfaction: A survey among geriatric care workers. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 62, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacavém, A., Cruz, R. V., Sousa, M., Rosário, A., & Gomes, J. S. (2019). An integrative literature review on leadership models for innovative organizations. Journal of Reviews on Global Economics, 8, 1741–1751. [Google Scholar]

- Saleem, S., Sajid, M., Arshad, M., Raziq, M. M., & Shaheen, S. (2024). Work stress, ego depletion, gender and abusive supervision: A self-Regulatory perspective. The Service Industries Journal, 44(5–6), 391–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, I. E. B. (2015). Transformational leadership: Relationship to job stress and job burnout in five-star hotels. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 15(4), 240–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, C., Coelho, A., Filipe, A., & Marques, A. M. A. (2023). The dark side of leadership: Abusive supervision and its effects on Employee’s behavior and well-being. Journal of Strategy and Management, 16(4), 672–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., & Gudergan, S. P. (2016). Guidelines for treating unobserved heterogeneity in tourism research: A comment on Marques and Reis (2015). Annals of Tourism Research, 57, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilpzand, P., De Pater, I. E., & Erez, A. (2016). Workplace incivility: A review of the literature and agenda for future research. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 37, S57–S88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, C., Soler, J., Vega, D., Nicolaou, S., Arias, L., & Pascual, J. C. (2024). How does mindfulness skills training work to improve emotion dysregulation in borderline personality disorder? Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation, 11(1), 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y., Liang, Z., Zhang, Y., Zhou, Y., Dong, S., Li, J., & Gao, G. (2025). Latent profiles of psychological resilience in patients with chronic disease and their association with social support and activities of daily living. BMC Psychology, 13(1), 792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srikanth, P. B. (2019). Coping with abusive leaders. Personnel Review, 49(6), 1309–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri, B., Thompson, J., Mistry, T. G., Okumus, B., & Gannon, M. (2024). Abusive supervision in commercial kitchens: Insights from the restaurant industry. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 120, 103789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenenhaus, M., Vinzi, V. E., Chatelin, Y.-M., & Lauro, C. (2005). PLS path modeling. Computational Statistics & Data Analysis, 48(1), 159–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepper, B. J. (2000). Consequences of abusive supervision. Academy of Management Journal, 43(2), 178–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepper, B. J. (2007). Abusive supervision in work organizations: Review, synthesis, and research agenda. Journal of Management, 33(3), 261–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsarenko, Y., Leo, C., & Tse, H. H. M. (2018). When and why do social resources influence employee advocacy? The role of personal investment and perceived recognition. Journal of Business Research, 82, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tummers, L. G., & Bakker, A. B. (2021). Leadership and job demands-resources theory: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 722080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogel, R. M., & Mitchell, M. S. (2017). The motivational effects of diminished self-esteem for employees who experience abusive supervision. Journal of Management, 43(7), 2218–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-J., Tsai, H.-T., & Tsai, M.-T. (2014). Linking transformational leadership and employee creativity in the hospitality industry: The influences of creative role identity, creative self-efficacy, and job complexity. Tourism Management, 40, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R., Jiang, J., Yang, L., & Shing Chan, D. K. (2016). Chinese employees’ psychological responses to abusive supervisors. Psychological Reports, 118(3), 810–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X. B., Huang, Z., Xu, X. S., Zhang, Y. F., & Yue, Y. (2023). Abusive supervision and teachers’ job vocational schools: The mediating effect of emotion regulation strategies. The International Journal of Educational Organization and Leadership, 30(2), 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C. E., Thomas, J. S., Bennett, A. A., Banks, G. C., Toth, A., Dunn, A. M., McBride, A., & Gooty, J. (2024). The role of discrete emotions in job satisfaction: A meta-analysis. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 45(1), 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B., Xiao, Y., Zhou, L., Li, F., & Liu, M. (2023). Why individuals with psychopathy and moral disengagement are more likely to engage in online trolling? The online disinhibition effect. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 45(2), 322–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xerri, M. J., Cozens, R., & Brunetto, Y. (2023). Catching emotions: The moderating role of emotional contagion between leader-member exchange, psychological capital and employee well-being. Personnel Review, 52(7), 1823–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S., Martinez, L. R., Van Hoof, H., Tews, M., Torres, L., & Farfan, K. (2018). The impact of abusive supervision and co-worker support on hospitality and tourism student employees’ turnover intentions in Ecuador. Current Issues in Tourism, 21(7), 775–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L., Duffy, M. K., & Tepper, B. J. (2018). Consequences of downward envy: A model of self-esteem threat, abusive supervision, and supervisory leader self-improvement. Academy of Management Journal, 61(6), 2296–2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y., Li, Y., Xu, S. T., & Li, G. (2022). It’s not just the victim: Bystanders’ emotional and behavioural reactions towards abusive supervision. Tourism Management, 91, 104506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zablah, A. R., Sirianni, N. J., Korschun, D., Gremler, D. D., & Beatty, S. E. (2017). Emotional convergence in service relationships: The shared frontline experience of customers and employees. Journal of Service Research, 20(1), 76–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H., & Jiang, Y. (2022). A systematic review of research on school bullying/violence in Mainland China: Prevalence and correlates. Journal of School Violence, 21(1), 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Hou, Z., Zhou, X., Yue, Y., Liu, S., Jiang, X., & Li, L. (2022). Abusive supervision: A content analysis of theory and methodology. Chinese Management Studies, 16(3), 509–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Yin, Y., & Su, W. (2024). The impact of servant leadership on proactive service behavior: A moderated mediation model. BMC Psychology, 12(1), 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H., & Guo, L. (2019). Abusive supervision and hospitality employees’ helping behaviors: The joint moderating effects of proactive personality and ability to manage resources. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 31(4), 1977–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y., Obeng, A. F., & Azinga, S. A. (2024). Supportive supervisor behavior and helping behaviors in the hotel sector: Assessing the mediating effect of employee engagement and moderating influence of perceived organizational obstruction. Current Psychology, 43(1), 757–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).