Counteracting Toxic Leadership in Education: Transforming Schools Through Emotional Intelligence and Ethical Leadership

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What are the key factors contributing to the emergence of toxic leadership in educational contexts?

- How do these toxic leadership behaviors impact educators and students?

- What strategies and interventions can be implemented to mitigate the negative effects of toxic leadership in schools?

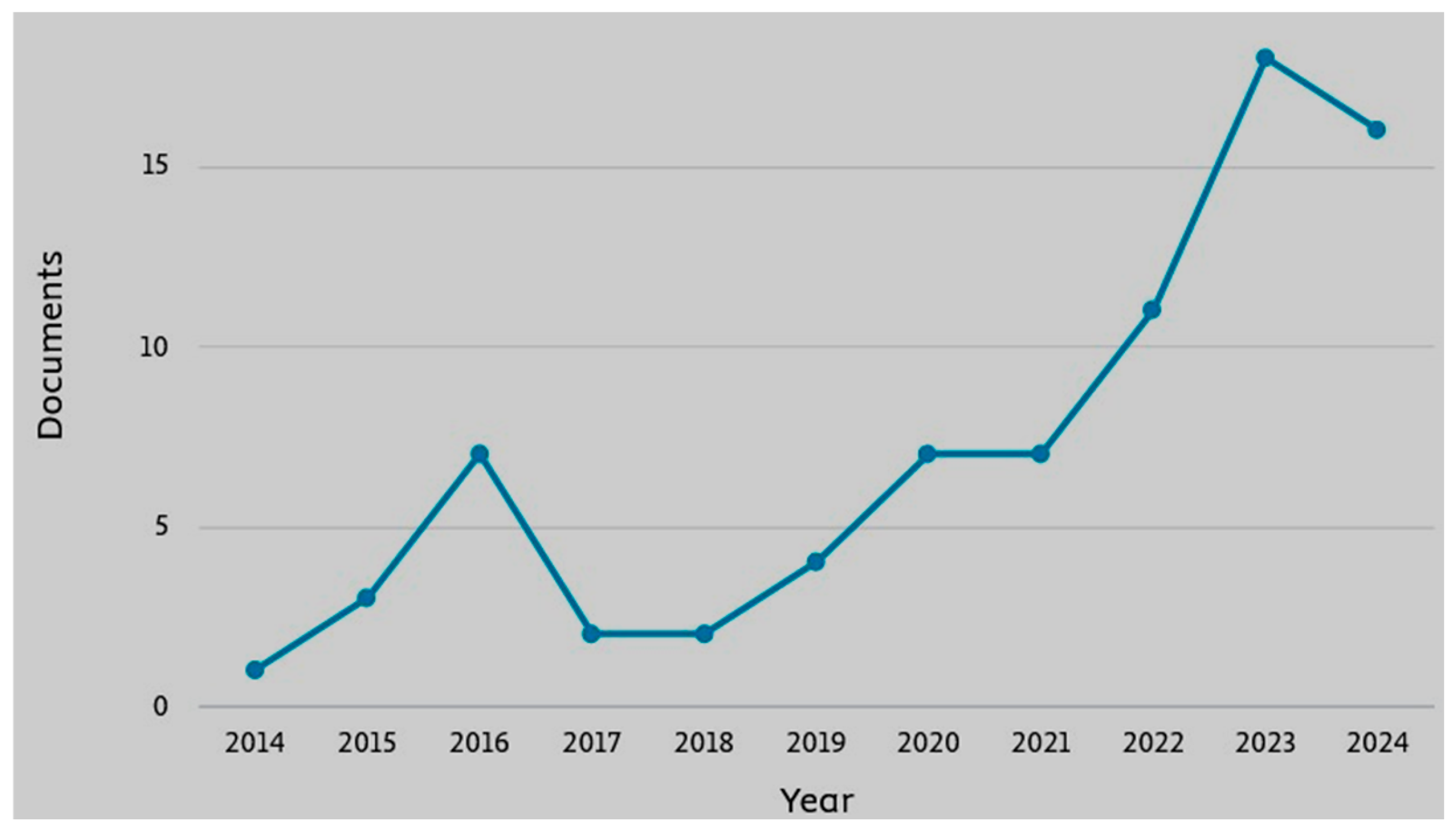

2. Literature Review Methodology

3. Key Concepts in Toxic Leadership

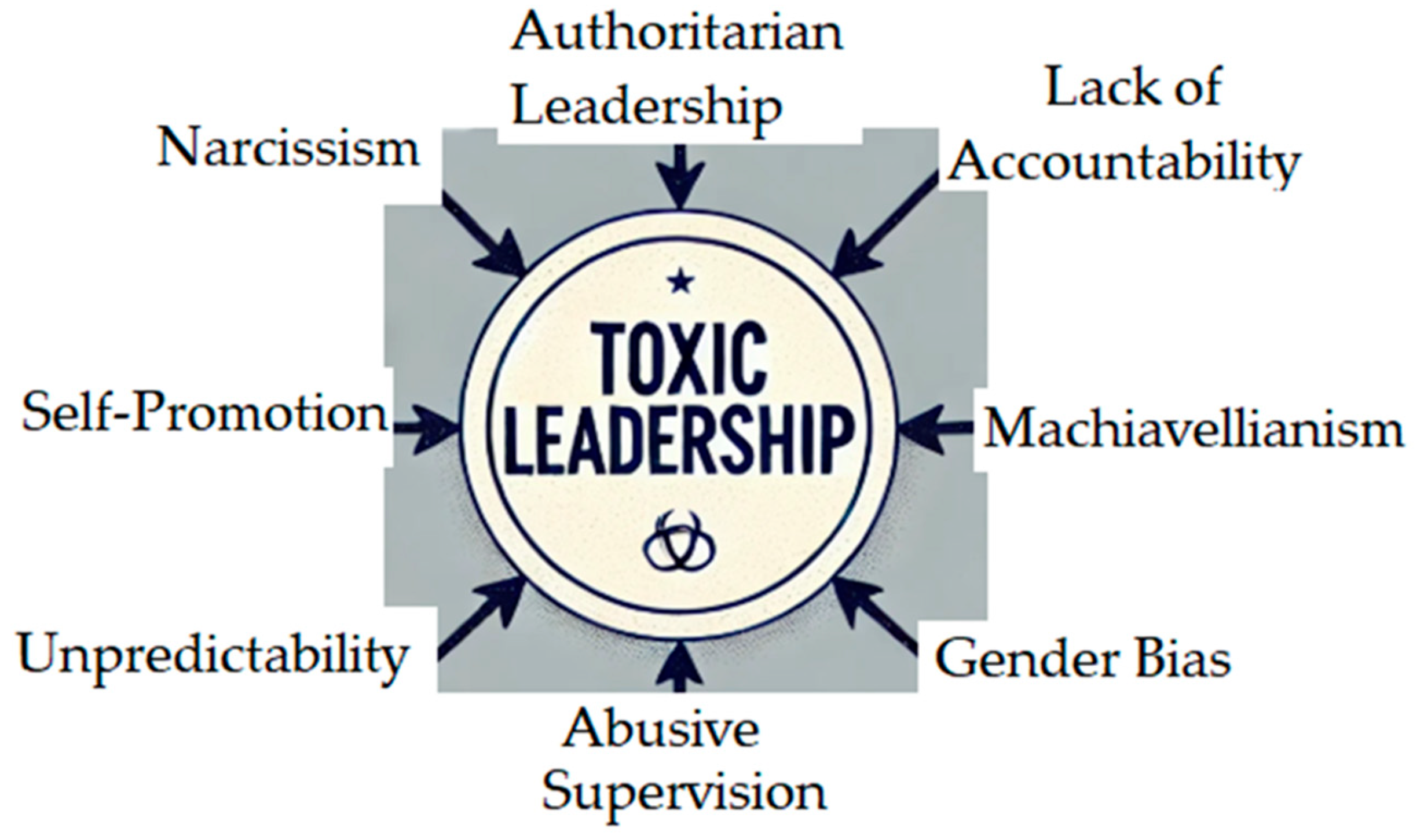

3.1. Common Traits of Toxic Leadership

- Authoritarian Leadership: Excessive control over others, limiting creativity and autonomy.

- Narcissism: Leaders with an inflated sense of self-importance, seeking personal gain.

- Self-Promotion: Prioritizing personal interests, avoiding responsibility and taking undue credit.

- Unpredictability: Erratic moods create an unstable work environment.

- Abusive Supervision: Hostile behaviors like belittling or unfairly holding subordinates accountable.

- Gender Bias: Teachers may experience gender discrimination or sexual harassment by their school leadership.

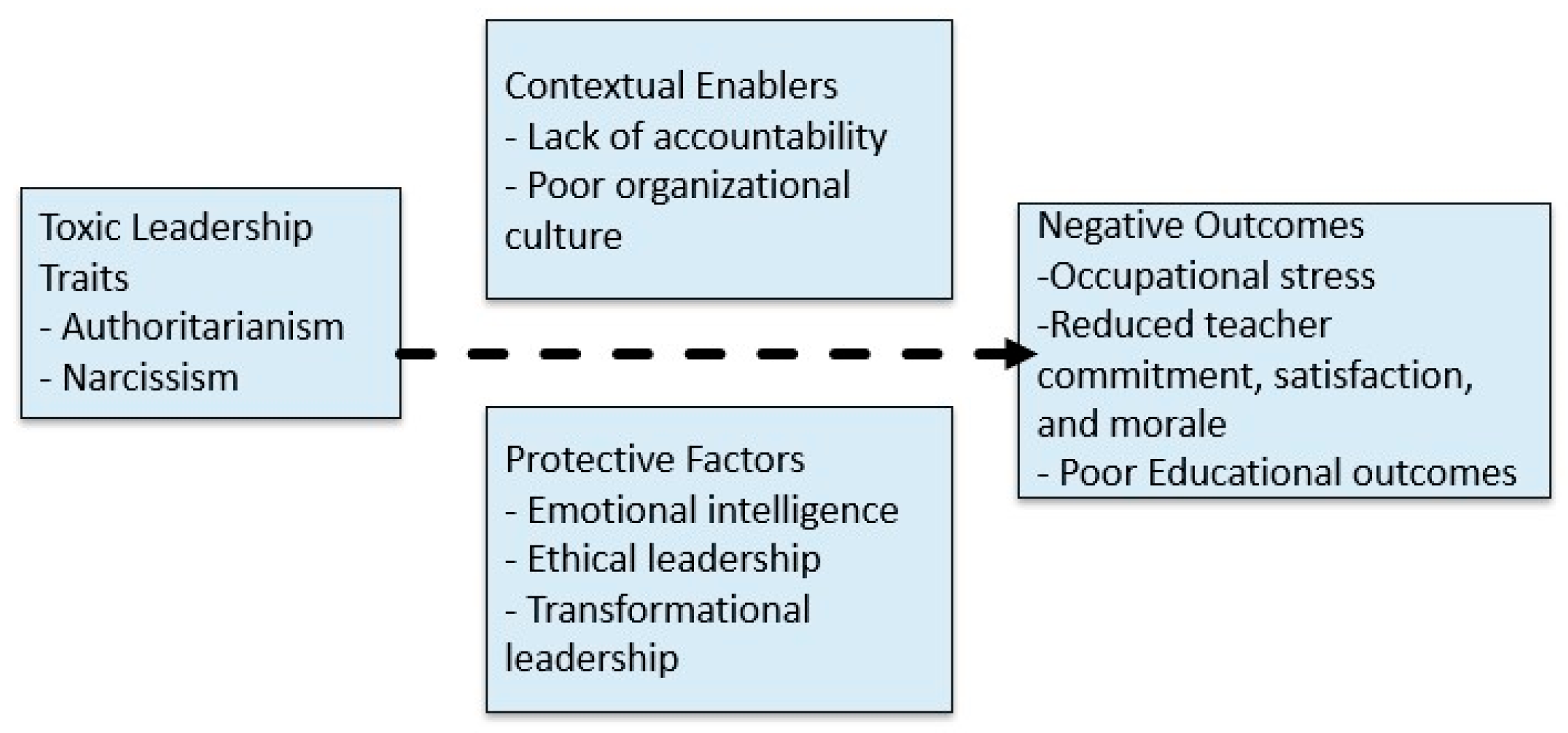

3.2. Contextual Factors Shaping Leadership Behavior and Effectiveness

3.3. Emotional Intelligence and Ethical Leadership as Antidotes

4. Strategies for Resilience and Emotional Intelligence

5. Success Stories with Examples and Case Studies

6. Transformational Leadership as a Potential Solution

7. Reducing the Proliferation of Dark Leadership

8. The Challenges of a Rapidly Changing Educational System

9. Discussion

10. Conclusions and Implications for Practical Measures

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahmed, M. A. O., Zhang, J., Fouad, A. S., Mousa, K., & Nour, H. M. (2025). The dark side of leadership: How toxic leadership fuels counterproductive work behaviors through organizational cynicism and injustice. Sustainability, 17, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanezi, A. (2024). Toxic leadership behaviours of school principals: A qualitative study. Educational Studies, 50(6), 1200–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasiou, S. (2025). Integrating human resource management and artificial intelligence in educational leadership: Pathways toward transformational change. Academic Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies, 14(3), 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasiou, S., & Ntokas, K. (2024). Leadership and quality enhancement in secondary education: A comparative analysis of TQM and EFQM. Merits, 4(4), 440–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasiou, S., & Papakonstantinou, G. (2015). Greek high school teachers’ views on principals’ duties, activities, and skills of effective school principals supporting and improving education. International Journal of Management in Education, 9(3), 340–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M. H., & Sun, P. Y. T. (2015). Reviewing leadership styles: Overlaps and the need for a new ‘full-range’ theory. International Journal of Management Reviews, 19(1), 76–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arar, K., & Saiti, A. (2022). Ethical leadership, ethical dilemmas and decision-making among school administrators. Equity in Education & Society, 1(1), 126–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyropoulou, E., & Lintzerakou, E. E. (2025). Contextual factors and their impact on ethical leadership in educational settings. Administrative Sciences, 15(1), 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, S. (2019). Dark side of leadership in educational setting. In IntechOpen eBooks. IntechOpen. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arifin, Y. (2024). The role of leadership in mitigating toxic workplace culture: A critical examination of effective interventions. The Journal of Academic Science, 1(4), 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armaou, M., Konstantinidis, S., & Blake, H. (2020). The effectiveness of digital interventions for psychological well-being in the workplace: A systematic review protocol. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(1), 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atasoy, R. (2020). The relationship between school principals’ leadership styles, school culture, and organizational change. International Journal of Progressive Education, 16(5), 256–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeez, F., & Aboobaker, N. (2024). Echoes of dysfunction: A thematic exploration of toxic leadership in higher education. Journal of Aggression, Conflict and Peace Research, 16(4), 439–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B. M. (2000). The future of leadership in learning organizations. Journal of Leadership Studies, 7(3), 18–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B. M., & Riggio, R. E. (2006). Transformational leadership. Psychology Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bess, J. L., & Goldman, P. (2001). Leadership ambiguity in universities and K–12 schools and the limits of contemporary leadership theory. The Leadership Quarterly, 12(4), 419–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boateng, P. A. (2023). Analyzing the relationship between psychopathy and leadership effectiveness: Moderating role of emotional intelligence. European Journal of Business and Management, 15, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Branson, C. M., Marra, M., & Kidson, P. (2024). Responding to the current capricious state of Australian educational leadership: We should have seen it coming! Education Sciences, 14, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, S., Kark, R., & Wisse, B. (2018). Editorial: Fifty shades of grey: Exploring the dark sides of leadership and followership. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandolia, E., & Anastasiou, S. (2020). Leadership and conflict management style are associated with the effectiveness of school conflict management in the region of Epirus, NW Greece. European Journal of Investigative Health Psychology & Education, 10, 455–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., Ning, R., Yang, T., Feng, S., & Yang, C. (2018). Is transformational leadership always good for employee task performance? Examining curvilinear and moderated relationships. Frontiers of Business Research in China, 12, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coetzer, M. F., Bussin, M., & Geldenhuys, M. (2017). The functions of a servant leader. Administrative Sciences, 7(1), 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conger, J. A. (1990). The dark side of leadership. Organizational Dynamics, 19(2), 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruickshank, A., & Collins, D. (2015). Illuminating and applying “the dark side”: Insights from elite team leaders. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 27(3), 249–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çoban, C. (2022). The dark side of leadership: A conceptual assessment of toxic leadership. Business Economics and Management Research Journal, 5(1), 50–61. [Google Scholar]

- Çoğaltay, N., & Boz, A. (2023). Influence of school leadership on collective teacher efficacy: A cross-cultural meta-analysis. Asia Pacific Education Review, 24(3), 331–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlan, M. A., Omar, R., & Kamarudin, S. (2024). Influence of toxic leadership behaviour on employee performance in higher educational institutions in Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Organizational Leadership, 13(1), 79–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L., Olafsen, A. H., & Ryan, R. M. (2017). Self-determination theory in work organizations: The state of a science. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 4(1), 19–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deluga, R. J. (1990). The effects of transformational, transactional, and laissez-faire leadership characteristics on subordinate influencing behavior. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 11(2), 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Wet, C., & Jacobs, L. (2021). Workplace bullying, emotional abuse and harassment in schools. In Special topics and particular occupations, professions and sectors (pp. 187–219). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğan, Ü., & Aslan, H. (2024). Investigation of the relationship between school principals’ toxic leadership behaviors and teachers’ perceptions of organizational gossip. International Journal of Psychology and Educational Studies, 11(2), 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eva, N., Robin, M., Sendjaya, S., van Dierendonck, D., & Liden, R. C. (2018). Servant leadership: A systematic review and call for future research. The Leadership Quarterly, 30(1), 111–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, T., Majeed, M., & Shah, S. Z. A. (2018). Jeopardies of aversive leadership: A conservation of resources theory approach. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, H. H. (2016). Is your organization run by the right kind of leader? An overview of the different leadership styles. SSRN Electronic Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friesen, S., & Brown, B. (2022). Teacher leaders: Developing collective responsibility through design-based professional learning. Teaching Education, 33(3), 254–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galdames-Calderón, M. (2023). Distributed leadership: School principals’ practices to promote teachers’ professional development for school improvement. Education Sciences, 13, 715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geroy, G. D., Bray, A., & Venneberg, D. L. (2008). The CCM model: A management approach to performance optimization. Performance Improvement Quarterly, 18(2), 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S. D., & Burkett, J. R. (2021). Almost a principal: Coaching and training assistant principals for the next level of leadership. Journal of School Leadership, 31(6), 502–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heenan, I. W., Paor, D. D., Lafferty, N., & McNamara, P. (2023). The impact of transformational school leadership on school staff and school culture in primary schools: A systematic review of international literature. Societies, 13(6), 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, K. E., & Raya, Z. T. (2023). Relationship between principals’ leadership styles and teachers’ behavior. Behavioral Sciences, 13(2), 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarra, S. T., Carranza, M. T. D. L. G., Morales, P. G., & Farias, J. P. G. (2023). Perceived distributed leadership, job satisfaction, and professional satisfaction among academics in Guanajuato universities. Merits, 3, 538–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iordanides, G. D., Bakas, T., Saiti, A. C., & Ifanti, A. A. (2014). Primary teachers’ and principals’ attitudes towards conflict phenomenon in schools in Greece. Multilingual Academic Journal of Education and Social Sciences, 2(2), 37–58. [Google Scholar]

- Itzkovich, Y., Heilbrunn, S., & Aleksic, A. (2020). Full range indeed? The forgotten dark side of leadership. Journal of Management Development, 39(7/8), 851–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamli, N. F. A., & Salim, S. S. S. (2020). Exploring the impact of emotional intelligence on headmaster leadership across primary schools in Malaysia based on gender. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 10(3), 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalkan, Ü., Altınay, F., Gazi, Z. A., Atasoy, R., & Dağlı, G. (2020). The relationship between school administrators’ leadership styles, school culture, and organizational image. SAGE Open, 10(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilag, O. K. T., Heyrosa-Malbas, M., Ibañez, D. D., Samson, G. A., & Sasan, J. M. (2023). Building leadership skills in educational leadership: A case study of successful school principals. International Journal of Scientific Multidisciplinary Research, 1(8), 913–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutouzis, M., & Malliara, K. (2017). Teachers’ job satisfaction: The effect of principal’s leadership and decision-making style. International Journal of Education, 9(4), 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, Y. J. (2002). Defining the effects of transformational leadership on organisational learning: A cross-cultural comparison. School Leadership & Management, 22(4), 439–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landay, K., Harms, P. D., & Credé, M. (2018). Shall we serve the dark lords? A meta-analytic review of psychopathy and leadership. Journal of Applied Psychology, 104(1), 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leithwood, K., & Sleegers, P. (2006). Transformational school leadership: Introduction. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 17(2), 143–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipman-Blumen, J. (2005). The allure of toxic leaders: Why followers rarely escape their clutches. Ivey Business Journal, 69(3), 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Lipman-Blumen, J. (2010). Toxic leadership: A conceptual framework. In Handbook of top management teams (pp. 214–222). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, T., Soares, A., & Palma-Moreira, A. (2025). Toxic leadership and turnover intentions: Emotional intelligence as a moderator of this relationship. Administrative Sciences, 15(1), 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackey, J. D., Ellen, B. P., McAllister, C. P., & Alexander, K. C. (2021). The dark side of leadership: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis of destructive leadership research. Journal of Business Research, 132, 705–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahlangu, V. P. (2017). The effects of toxic leadership on teaching and learning in South African township schools [Master’s thesis, University of Pretoria]. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/2263/45663 (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- McCleskey, J. A. (2013). The dark side of leadership: Measurement, assessment, and intervention. Business Renaissance Quarterly, 8, 35–48. [Google Scholar]

- Mehraein, V., Visintin, F., & Pittino, D. (2023). The dark side of leadership: A systematic review of creativity and innovation. International Journal of Management Reviews, 25(4), 740–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, M. S., Rivera, G., & Treviño, L. K. (2023). Unethical leadership: A review, analysis, and research agenda. Personnel Psychology, 76(2), 547–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasim, F., Khurshid, K., Akhtar, S., & Kousar, F. (2023). Connecting the dot: Understanding the link between secondary school heads’ leadership styles and teacher performance. Pakistan Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 11(2), 1643–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netolicky, D. M. (2020). School leadership during a pandemic: Navigating tensions. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 49(3), 393–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Or, M. H., & Berkovich, I. (2023). Participative decision making in schools in individualist and collectivist cultures: The micro-politics behind distributed leadership. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 51(3), 533–553. [Google Scholar]

- Orunbon, N. O., & Ibikunle, G. A. (2023). Principals’ toxic leadership behaviour and teachers’ workplace incivility in public senior secondary schools, Lagos State, Nigeria. EduLine: Journal of Education and Learning Innovation, 3(2), 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, J. C., Mackey, J. D., McAllister, C. P., Alexander, K. C., Phillipich, M. A., Mercer, I. S., & Ellen, B. P., III. (2025). Cultural values as moderators of the relationship between destructive leadership and followers’ job satisfaction. Group & Organization Management, 50(4), 1255–1295. [Google Scholar]

- Panagopoulos, N., & Anastasiou, S. (2023, January 20–22). Emotional intelligence and educational leadership. ICOMEU ‘23: Proceedings of the International Conference on Management and Educational Updates (pp. 101–104), Thessaloniki, Greece. Available online: https://www.icomeu.gr/ICOMEU%202023%20EDITED%20BOOK.pdf#page=104 (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Panagopoulos, N., Karamanis, K., & Anastasiou, S. (2023). Exploring the impact of different leadership styles on job satisfaction among primary school teachers in the Achaia region, Greece. Education Sciences, 14(1), 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulhus, D. L., & Williams, K. M. (2002). The dark triad of personality: Narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy. Journal of Research in Personality, 36, 556–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelletier, K. L. (2010). Leader toxicity: An empirical investigation of toxic behavior and rhetoric. Leadership, 6(4), 373–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S., & Huang, Y. (2024). Teachers’ authoritarian leadership and students’ well-being: The role of emotional exhaustion and narcissism. BMC Psychology, 12, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purwani Setyaningrum, R., Setiawan, M., & Wirawan Irawanto, D. (2020). Servant leadership characteristics, organizational commitment, followers’ trust, and employees’ performance outcomes: A literature review. European Research Studies Journal, 23, 902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, A., Amin, R., & Ahmad, S. (2019). Relationship between teachers’ leadership styles and students’ academic achievement. Global Social Sciences Review, IV, 360–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, R., Teixeira, N., & Costa, B. (2024). The impact of perceived leadership effectiveness and emotional intelligence on employee satisfaction in the workplace. Merits, 4(4), 490–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, F., Malik, M. I., Hyder, S., & Perveen, A. (2022). Toxic leadership and project success: Underpinning the role of cronyism. Behavioral Sciences, 12, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sam, C. H. (2021). What are the practices of unethical leaders? Exploring how teachers experience the “dark side” of administrative leadership. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 49(2), 303–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schyns, B., & Schilling, J. (2013). How bad are the effects of bad leaders? A meta-analysis of destructive leadership and its outcomes. The Leadership Quarterly, 24(1), 138–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N., Sengupta, S., & Dev, S. (2019). Toxic leadership: The most menacing form of leadership. IntechOpen eBooks. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snow, N., Hickey, N., Blom, N., O’Mahony, L., & Mannix-McNamara, P. (2021). An exploration of leadership in post-primary schools: The emergence of toxic leadership. Societies, 11(2), 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spain, S. M., Harms, P. D., & Wood, D. (2016). Stress, well-being, and the dark side of leadership. In W. A. Gentry, P. L. Perrewé, J. R. B. Halbesleben, & C. C. Rosen (Eds.), The role of leadership in occupational stress (Vol. 14, pp. 33–59). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şenol, N., & Taş, S. (2024). The corrosive effect of school administrators as toxic leaders on teacher accountability. Kastamonu Education Journal, 32(4), 702–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timur, K., & Duygu, T. Y. (2024). Review of articles published between 2014 and 2023 on toxic leadership using bibliometric analysis: Comparison of DergiPark and Web of Science databases. Istanbul Management Journal, 97, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travis, J., Neale, C. A., & Wilgus, S. J. (2024). When dark personality gets darker: The intersection of injustice, moral disengagement, and unethical decision making. Merits, 4(4), 414–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzortsos, E., & Anastasiou, S. (2025). Toxic leadership in Greek primary education: Impacts on teachers’ job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Societies, 15(7), 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhl-Bien, M., & Carsten, M. K. (2007). Being ethical when the boss is not. Organizational Dynamics, 36(2), 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera, D., Samba, C., Kong, D. T., & Maldonado, T. (2020). Resilience as thriving. Organizational Dynamics, 50(2), 100784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldman, D. A., Siegel, D. S., & Javidan, M. (2006). Components of CEO transformational leadership and corporate social responsibility. Journal of Management Studies, 43(8), 1703–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windsor, D. (2017). The dark side of leadership practices: Variations across Asia. In N. Muenjohn, & A. McMurray (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of leadership in transforming Asia (pp. 125–141). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolor, C. W., Ardiansyah, A., Rofaida, R., Nurkhin, A., & Rababah, M. A. (2022). Impact of toxic leadership on employee performance. Health Psychology Research, 10(4), 57551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, Y., Zhang, L., & Li, M. (2019). Abusive leadership and helping behavior: Capability or mood, which matters? Current Psychology, 38(1), 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yengkopiong, J. P. (2024). The paradox of leadership: Toxic education leadership in learning institutions. East African Journal of Education Studies, 7(1), 90–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S., Liu, M., Xi, M., Zhu, C. J., & Liu, H. (2023). The role of leadership in human resource management: Perspectives and evidence from China. Asia Pacific Business Review, 29(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Toxic Leadership Behavior | Strategy | Advantages | Limitations | Relevant References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Micromanagement | Emotional Intelligence Training | Improves empathy, reduces control-based behaviors | It may take time to see significant changes | Azeez and Aboobaker (2024); Schyns and Schilling (2013) |

| Lack of Empathy | Leadership Development Programs | Fosters understanding and trust | Requires commitment from school leaders | Peng and Huang (2024); Schyns and Schilling (2013) |

| Aggressive Communication | Conflict Resolution Workshops | Reduces hostility, fosters open communication | Requires leaders to be receptive to feedback | Şenol and Taş (2024) |

| Authoritarian Control | Collaborative Leadership Models | Increases teacher involvement, enhances cooperation | May face resistance from traditional leadership styles | Orunbon and Ibikunle (2023); Yengkopiong (2024) |

| Teacher Alienation | Mentorship and Peer Support Programs | Reduces isolation, increases teacher morale | Needs a supportive environment for success | Friesen and Brown (2022) |

| Unethical Behavior/Favoritism | Cultural and Ethical Leadership Training | Promotes fairness and inclusivity | Requires ongoing reinforcement and commitment | Yengkopiong (2024); Azeez and Aboobaker (2024) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Anastasiou, S. Counteracting Toxic Leadership in Education: Transforming Schools Through Emotional Intelligence and Ethical Leadership. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 312. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15080312

Anastasiou S. Counteracting Toxic Leadership in Education: Transforming Schools Through Emotional Intelligence and Ethical Leadership. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(8):312. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15080312

Chicago/Turabian StyleAnastasiou, Sophia. 2025. "Counteracting Toxic Leadership in Education: Transforming Schools Through Emotional Intelligence and Ethical Leadership" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 8: 312. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15080312

APA StyleAnastasiou, S. (2025). Counteracting Toxic Leadership in Education: Transforming Schools Through Emotional Intelligence and Ethical Leadership. Administrative Sciences, 15(8), 312. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15080312