1. Introduction

Organizational culture, defined by

Schein (

2004) as the set of values, beliefs, norms and practices shared within an organization, has been taking on an increasingly central role in the study of organizations. The academic literature has shown considerable interest in the study of organizational culture due to its significant implications for employee performance and organizational success (

Carvalho et al., 2023). Organizational culture involves sharing a set of values, attitudes, assumptions, and beliefs among all individuals who are part of an organization (

Ouellette et al., 2020;

Yip et al., 2020). Organizational culture has been analyzed from various perspectives, such as exploring the role that culture can play in sustainable practices encouraged by organizations (

Stojanovic et al., 2020) and how organizational culture can be affected by various factors (

Polyanska et al., 2019). From the perspective of

Salvador et al. (

2022), the perception of organizational culture can be seen as an indicator of the quality of organizational support. In this scenario, the perception of organizational support (POS), conceptualized by

Eisenberger et al. (

1986), which considers the extent to which employees believe the organization values their contributions and cares about their well-being, has been identified as a crucial factor. Studies show that employees who perceive high support from the organization tend to have higher levels of motivation and loyalty and superior performance in their roles (

Darolia et al., 2010;

Huang, 2025;

Li et al., 2022;

Rhoades & Eisenberger, 2002).

Motivation at work, understood as the set of internal or external forces that influences how employees act to achieve their professional goals (

Deci & Ryan, 1985), is intrinsically linked to POS. In turn, performance, which refers to the level of effectiveness and efficiency with which tasks are performed (

Deal & Kennedy, 1982), is a key indicator for measuring an employee’s contribution to organizational results. According to

Forson et al. (

2021), motivation can be considered a predictor of performance.

The intersection between organizational culture and perceived organizational support provides fertile ground for understanding the mechanisms that drive employee motivation and performance. Companies that promote a strong, transparent, and inclusive organizational culture tend to create environments where employees feel more supported and motivated to achieve high levels of performance while also demonstrating greater loyalty to the organization (

Schein, 2010). This relationship can be interpreted in light of social identity theory (

Tajfel, 1978); according to this theory, when employees feel like members of the organization to which they belong, absorbing its characteristics, such as the perception of organizational support, their performance tends to improve.

However, a gap remains in the literature regarding the synthesis of the main dimensions, perspectives, and orientations of organizational culture (

Tadesse Bogale & Debela, 2024). The relevance of this topic becomes even more evident when considering the relationship between organizational culture and organizational outcomes. In an era where organizations face complex challenges, understanding how organizational culture influences perceptions of support and, ultimately, employee motivation and performance is essential to creating positive and productive work environments. This study is particularly relevant in the Portuguese organizational context, where there is a growing need to understand the cultural and support dynamics that can improve talent retention and competitiveness.

In this context, the present research seeks to answer the following central question: What is the influence of organizational culture on the perception of organizational support and its relationship with employee motivation and performance? Although there are studies that address the relationship between organizational culture and performance (

Hung et al., 2022;

Strengers et al., 2022), few explore the perception of organizational support as a mediator of this process, especially in the Portuguese context. This study aims to fill this gap and provide a theoretical model that explains the interactions between these three constructs in the organizational environment.

The objective of this investigation is, therefore, to analyze the influence of organizational culture on the perception of organizational support and its relationship with employee motivation and perceived performance. Through theoretical and empirical analysis, we aim to identify which aspects of organizational culture contribute most to a high perception of organizational support and, at the same time, understand how this perception translates into increased motivation and improved employee-perceived performance.

These factors are crucial in today’s job market, where talent retention and productivity are essential pillars for sustainable organizational success. Thus, organizations that manage to align their culture with practices that foster a positive perception of support are better positioned to face the challenges of the contemporary business environment and achieve lasting competitive advantages.

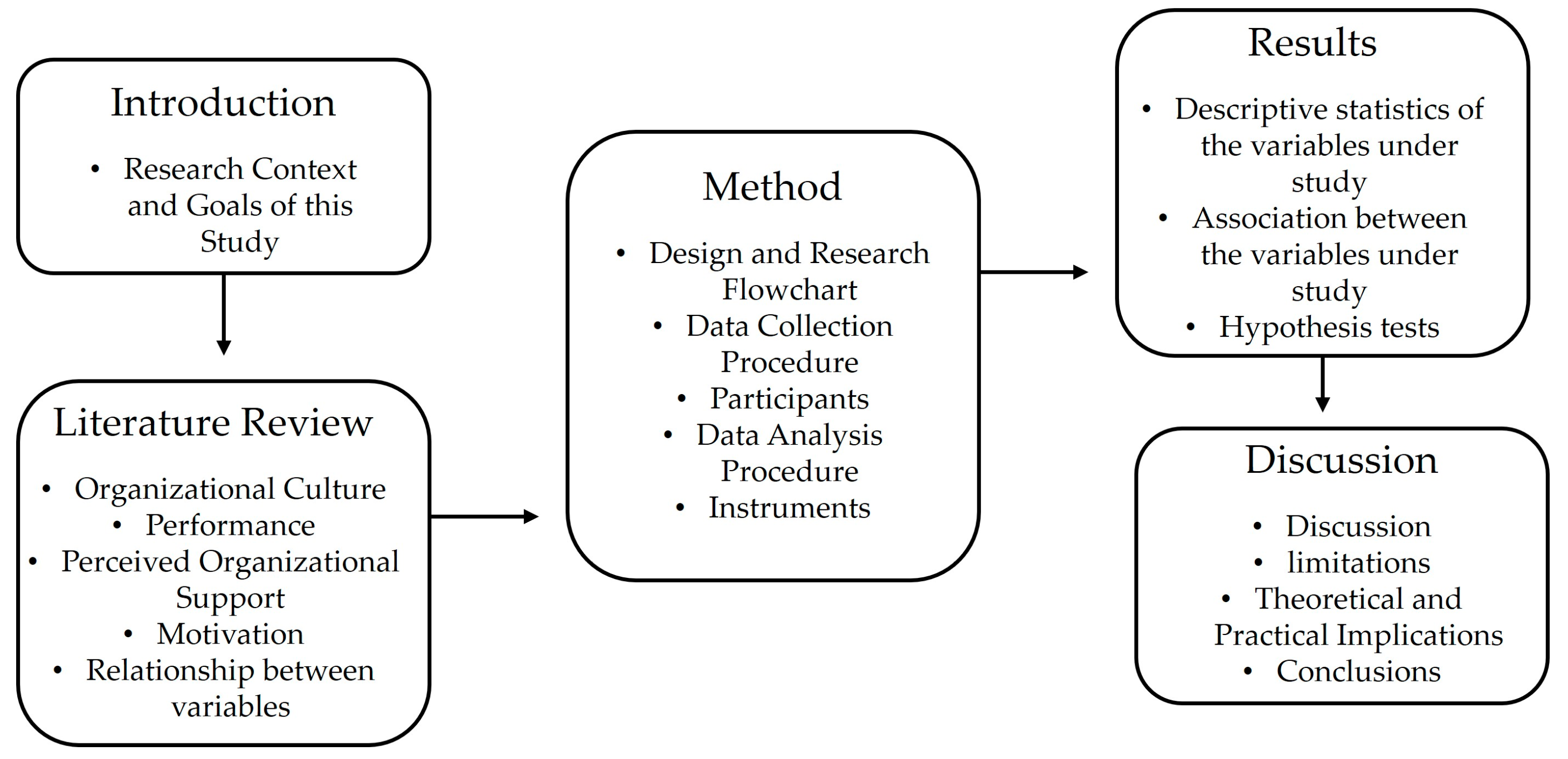

This study is structured in six sections:

Section 1—Introduction, explaining the relevance of the study.

Section 2—Literature review, reviewing the literature on the constructs studied and the relationship between them. Ultimately, the research model is presented.

Section 3—Methodology, which presents the Design and Research Flowchart, explains the data collection and analysis procedure, presents the instruments used in this study, and describes the sample.

Section 4—Results, which presents the descriptive statistics of the variables under study, studies the association between the variables under study, and tests the hypotheses formulated.

Section 5—Discussion, where the results obtained are discussed. The limitations, practical implications, and theoretical implications are presented.

Section 6—Conclusions, where the main conclusions of this study are presented.

4. Results

Two models were tested: one with a single factor and one with 11 factors. Almost all adjustment indices for the one-factor model proved inadequate (χ2/df = 4.10; GFI = 0.47; CFI = 0.57; TLI = 0.55; RMSEA = 0.102; RMSR = 0.165). On the other hand, the fit indices for the 11-factor model were almost all adequate (χ2/df = 1.60; GFI = 0.81; CFI = 0.92; TLI = 0.91; RMSEA = 0.045; RMSR = 0.112). As can be seen, only the GFI is below 0.90; however, this is acceptable since it is above 0.80. These results indicate that theoretical conceptualization, which determines eleven variables, adequately represents the observed data. The correlations are consistent with the theorized pattern of relationships.

Next, the average of each dimension or instrument used in this study was calculated. When calculating the average values, the ordinal variables were transformed into quantitative variables, allowing for the following tests to be performed: Student’s t-test for one sample, Student’s t-test for independent samples, one-way ANOVA, Pearson correlations, and linear regression.

4.1. Descriptive Statistics of the Variables Under Study

To understand the participants’ responses to the constructs studied, descriptive statistics were performed on the variables under examination. For this purpose, Student t-tests were performed on a sample.

Except for innovative culture, all participants’ responses regarding organizational culture are significantly above the midpoint of the scale (3.5) (

Table 2). These results indicate that the participants in this study perceive a high level of support, a goal-oriented culture, and a rule-oriented culture. The dimension with the highest average is rule-oriented culture.

Both affective and cognitive perceptions of organizational support are also significantly above the midpoint of the scale (4), which means that the participants in this study have a high perception of organizational support (

Table 2).

Regarding perceived performance, it is evident that the participants’ responses are significantly above the midpoint of the scale (3), with a very high value (

Table 2). This result indicates a generally high perception of performance by the participants.

Regarding motivation, it is evident that, except introjected motivation, all dimensions are significantly above the midpoint (3) (

Table 2). These results indicate that the participants in this study demonstrate high levels of intrinsic motivation, identified motivation, and extrinsic motivation, with the former having the highest average value. These data suggest that, in general, participants engage in their tasks out of personal interest, satisfaction, or appreciation for their content rather than internal pressures or external rewards. Introjected motivation, in turn, has a meaning close to the midpoint and is not statistically significant, indicating that participants’ behaviors are not highly motivated by feelings of obligation, guilt, or internal impositions.

As the sample for this study consists of participants working in Angola and Portugal, it was decided to verify whether the fact that they live and work in different countries had a significant effect on the variables under study. To this end, several Student t-tests were carried out for independent samples.

The country exhibits a statistically significant effect on only some specific variables under study (

Table 3). Regarding the support culture, participants from Portugal reported significantly higher levels than those from Angola (

Table 3). This result suggests that Portuguese individuals perceive, on average, an organizational environment that is more oriented towards interpersonal support, cooperation, and employee appreciation.

In the case of innovation culture, a statistically significant difference was also observed, with Portuguese participants scoring higher than Angolan participants (

Table 3). This finding indicates that respondents in Portugal perceive their organizations as more open to creativity, change, and experimentation with new ideas.

Regarding introjected motivation, the results show that Angolan participants exhibit significantly higher levels than Portuguese participants (

Table 3). This difference suggests that employees in Angola are more likely to act out of internal pressures, such as a sense of obligation or a desire to avoid blame, which may reflect cultural differences in the internalization of organizational norms.

Finally, a statistically significant effect of country was also observed on extrinsic motivation, with Angolan participants revealing higher levels in this dimension (

Table 3). This result indicates that, on average, individuals from Angola attach greater importance to external factors, such as tangible rewards, incentives, or formal recognition, in their work relationships.

4.2. Association Between the Variables Under Study

The supportive culture is positively and significantly correlated with perceived performance, as well as with perceptions of affective and cognitive organizational support, and with intrinsic, identified, and introjected motivation (

Table 4). These results suggest that organizational contexts characterized by interpersonal support and positive involvement are associated with higher levels of motivation and perceived support, as well as better perceived performance evaluation.

The culture of innovation also reveals positive and significant correlations with perceived performance, as well as with both dimensions of perceived organizational support and all forms of motivation analyzed, with particular emphasis on intrinsic and identified motivation (

Table 4). This pattern suggests that innovative organizational environments are associated with greater employee engagement, both in terms of motivation and perceived institutional support, as well as perceived performance.

In the rule-based culture, there are also positive and statistically significant associations with perceived performance, as well as with both dimensions of perceived organizational support and with the more self-determined forms of motivation (

Table 4). These results show that even more structured organizational contexts, when well perceived, can contribute positively to employee engagement and effectiveness.

Perceived performance shows positive and significant correlations with perceptions of affective and cognitive organizational support, as well as intrinsic and identified motivation, and with all dimensions of organizational culture analyzed (

Table 4). These results show that a favorable organizational environment, in terms of culture and support, is associated with a greater sense of effectiveness at work.

The perception of affective organizational support is positively correlated with all dimensions of the organizational culture under study, as well as with perceived performance and all forms of motivation, especially intrinsic motivation (

Table 4). This pattern reinforces the importance of affective relationships within organizations, which enhance the well-being and perceived performance of employees.

The perception of cognitive organizational support exhibits positive and statistically significant correlations with all dimensions of organizational culture (support, objectives, innovation, and rules), as well as with perceived performance and all forms of motivation analyzed (

Table 4). These results indicate that the greater the employees’ perception that the organization values their contributions and cares about their well-being rationally and instrumentally, the greater their involvement, motivation, and perception of effectiveness at work tend to be.

4.3. Hypotheses

Hypotheses 1–3 and 5 were tested using multiple linear regressions with the stepwise method. This method allows the removal of a variable whose importance in the model is reduced by the addition of new variables. This method is appropriate when there are significant correlations between the independent variables (

Marôco, 2021). As the independent variables are significantly correlated (

Table 4), this method was chosen.

The results indicate that only the goal culture (β = 0.17,

p = 0.009) and the rule culture (β = 0.15,

p = 0.025) have a positive and significant effect on perceived performance (

Table 5). The model explains 7% of the variability in perceived performance (

Table 5). The model is statistically significant (F (2, 297) = 12.68;

p < 0.001) (

Table 5).

The results indicate that both the supportive culture (β = 0.69,

p < 0.001) and goal culture (β = 0.12,

p = 0.012) have a positive and statistically significant effect on perceived affective organizational support (

Table 6). There is also a significant effect of the country on the perception of affective organizational support (β = 0.09,

p = 0.021). For participants working in Portugal, the perception of affective organizational support is stronger than for participants working in Angola. The model explains 56% of the variability in perceived affective organizational support (

Table 6). The model is statistically significant (F (3, 296) = 129.66;

p < 0.001) (

Table 6).

The results indicate that a supportive culture (β = 0.66;

p < 0.001) and a goal culture (β = 0.28;

p < 0.001) have a positive and statistically significant effect on perceived cognitive organizational support, while rule culture (β = −0.16;

p = 0.004) and innovative culture (β = −0.17;

p = 0.020) have a negative and significant effect on the same variable (

Table 6). The model explains 41% of the variability in perceived cognitive organizational support (

Table 6). The model is statistically significant (F (4, 295) = 52.39;

p < 0.001) (

Table 6).

The results indicate that perceived affective organizational support has a positive and statistically significant effect on perceived performance (β = 0.26;

p = 0.008) (

Table 7). The model explains 6% of the variability in perceived performance (7). The model is statistically significant (F (1, 298) = 21.06;

p < 0.001) (

Table 7).

As Hypothesis 4 assumed a mediating effect, the procedures outlined by

Baron and Kenny (

1986) were followed.

A multiple linear regression was performed in two steps. In the first step, the predictor variable was introduced as the independent variable, and in the second step, the mediating variable was introduced.

The results indicate that perceived affective organizational support has a partial mediating effect on the relationship between goal culture and perceived performance (

Table 8). When the mediating variable was introduced into the regression equation, the effect of goal culture on perceived performance remained significant but decreased in intensity (

Table 8). The model explains 8% of the variability in perceived performance (

Table 8). The increase in variability is statistically significant (ΔR

2a = 0.02,

p < 0.01) (

Table 8. Both models are statistically significant (F) (

Table 8).

The Sobel test confirmed the partial mediation effect (Z = 2.28; p = 0.022).

The results reveal that the identified motivation has a positive and statistically significant effect on perceived performance (β = 0.29;

p < 0.001) (

Table 9). The model explains 8% of the variability in perceived performance (

Table 10). The model is statistically significant (F (1, 298) = 26.65;

p < 0.001) (

Table 9).

Hypothesis 6 was tested in Macro Process 4.2 (Model 1), developed by

Hayes (

2022). The results indicate that intrinsic motivation (B = 0.10;

p < 0.001) and identified motivation (B = 0.09;

p = 0.003) have a moderating effect on the relationship between supportive culture and performance (

Table 10).

For participants who have high intrinsic and identified motivation, a supportive culture becomes particularly relevant in enhancing their performance compared to those with low intrinsic and identified motivation.

The results indicate that intrinsic motivation (B = 0.10;

p < 0.001) and identified motivation (B = 0.06;

p = 0.011) have a moderating effect on the relationship between support culture and performance (

Table 11).

For participants with high intrinsic and identified motivation, compared to those with low intrinsic and identified motivation, the goal culture becomes more relevant in enhancing their performance.

The results indicate that intrinsic motivation (B = 0.10;

p < 0.001) and identified motivation (B = 0.06;

p = 0.043) have a moderating effect on the relationship between innovative culture and performance (

Table 12).

For participants with high intrinsic and identified motivation, compared to those with low intrinsic and identified motivation, innovative culture becomes more relevant to enhancing their performance.

The results indicate that intrinsic motivation (B = 0.11;

p < 0.001) and identified motivation (B = 0.10;

p = 0.004) have a moderating effect on the relationship between rule culture and performance (

Table 13).

For participants with high intrinsic and identified motivation, compared to those with low intrinsic and identified motivation, rule culture become more relevant in enhancing their performance.

5. Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the effect of organizational culture on employee-perceived performance and whether this relationship is mediated by the perception of organizational support and moderated by employee motivation.

First, it was confirmed that only goal culture and rule culture have a positive and significant effect on perceived performance. These results align with the existing literature. According to

Aggarwal (

2024), different dimensions of organizational culture have varying impacts on employee-perceived performance, highlighting the complexity of this relationship. When employees feel that they are part of the organization where they work and value its culture, they tend to improve their performance, thereby helping them to achieve organizational goals. This relationship can be interpreted in light of the Reciprocity Norm (

Gouldner, 1960).

Secondly, the results reveal that the support culture and the goal culture have a positive and significant effect on the perception of organizational support, both in its affective and cognitive dimensions. In turn, the country also has a significant negative effect on the perception of affective organizational support. For participants working in Portugal, the perception of affective organizational support is stronger than for participants working in Angola. However, it was found that rule culture and innovation culture have a negative and significant effect on the cognitive perception of organizational support. In a study conducted by

Salvador et al. (

2022), the culture of rules also had a negative and significant effect on the perception of cognitive organizational support. It should also be noted that among the dimensions of organizational culture, supportive culture has the strongest effect on both affective and cognitive perceived organizational support. These results suggest that, although specific dimensions of organizational culture promote the perception of support, others may have the opposite effect, possibly because they are associated with more rigid structures or environments that are less open to autonomy. This pattern confirms the arguments of

Aggarwal (

2024), who argues that the effects of organizational culture are not uniform and highlights the complexity of the relationship between culture and perceptions of organizational support. Innovative culture is not well understood, as innovative people, both in Angola and Portugal, go against the norm (seeking achievement and success rather than quality of life) and may suffer ostracism or worse (dismissal) (

Walter & Au-Yong-Oliveira, 2022), since negative organizations (where there is no meritocracy) abound (

Graça & Au-Yong-Oliveira, 2024) in these relationship cultures (as opposed to transactional cultures, found only in the US and Canada) (

Solomon & Schell, 2009). Rule cultures also run counter to the desire for benevolent autocrats in these cultures (

The Culture Factor Group, 2025)—since rules hold people accountable, rather than allowing them to “get away with” inferior work, organizational commitment, and/or competence. When employees realize that they are members of the organization where they work, they absorb their characteristics, including POS. This relationship can be interpreted through social identity theory, developed by

Tajfel (

1978).

Thirdly, the results showed that the perception of affective organizational support has a positive and statistically significant effect on perceived performance. This association suggests that the greater the employees’ understanding that the organization values their contributions and cares about their well-being, the greater their perception of effectiveness at work tends to be. These results are consistent with the theoretical frameworks of

Eisenberger et al. (

1986) and

Rhoades and Eisenberger (

2002), which highlight the direct impact of organizational support on employee attitudes and behaviors. This result further reinforces the idea that organizational contexts that promote clarity, recognition, and trust in labor relations enhance individual performance.

Tamimi et al. (

2023) highlight a positive relationship between perceived support and performance, reinforcing the idea that organizations that offer a supportive environment tend to have more satisfied and effective employees. When an employee perceives a high level of support from the organization, they strive to reciprocate with improved performance, thereby contributing to the achievement of organizational goals. This relationship can be interpreted through social exchange theory (

Blau, 1964).

Fourthly, the results confirm that the perceived affective organizational support was found to have a partial mediating effect on the relationship between the goal culture and perceived performance. These results are in line with the literature, which recognizes the role of organizational support as an explanatory mechanism between cultural practices and employee behavior. According to

Baron and Kenny (

1986), a partial mediation effect occurs when the mediating variable reduces, but does not eliminate, the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable, as found in this study. From the perspective of

Eisenberger et al. (

2001), affective support reinforces employees’ commitment to the organization, enhancing their performance. These results reinforce the idea that different psychosocial mechanisms are involved in how organizational culture influences individual outcomes, highlighting the complexity of these interactions, as already pointed out by

Aggarwal (

2024). These relationships can be understood in the context of various theories. When employees perceive themselves as members of the organization where they work, they absorb its characteristics, including POS (social identity theory), and reciprocate this support by working hard to improve their performance, thereby helping to achieve organizational goals (social exchange theory).

Fifthly, the motivation identified was shown to have a positive and significant effect on perceived performance. These results align with the existing literature, which associates high levels of autonomous motivation with enhanced engagement and professional performance. According to the self-determination theory, when individuals identify with their tasks and recognize their value, they tend to show greater commitment and effectiveness (

Deci & Ryan, 1985;

Gagné & Deci, 2005). From the perspective of

Luthans and Youssef (

2007), identified motivation, which involves a conscious internalization of the organization’s goals, contributes significantly to the sustained performance of employees.

Sixthly, the results indicated that intrinsic motivation and identified motivation moderate the relationship between organizational culture and perceived performance. These results align with the existing literature.

Yusof et al. (

2017) found that motivation, influenced by work attitudes, can act as a moderator in other organizational relationships. It is worth noting that only intrinsic motivation and identified motivation have a moderating effect on the relationship between organizational culture and performance. When combined, these two dimensions of motivation (intrinsic and identified) are considered autonomous motivation (

Gagné et al., 2015;

Ryan & Deci, 2000). According to these authors, autonomous motivation is associated with higher levels of performance and is characterized by behaviors of strong commitment to work.

Regarding the descriptive statistics of the variables under study, all variables are significantly above the midpoint of the scale, except for innovation culture and introjected motivation. Among the four dimensions of organizational culture (supportive culture, goal culture, innovation culture, and rule culture), the one with the highest average is rule culture. These results align with the existing literature. According to

Hofstede (

1991), Portugal is a country where hierarchical distance is very high, and in an organization with a rule-based culture, there is a very vertical hierarchy. We should also point out that when the association between gender and rule-oriented culture was analyzed, it was found that female participants had a higher perception of rule-oriented culture than male participants. Once again, these results align with the existing literature. In a study conducted by

Rebelo et al. (

2024) on women’s perceptions of discrimination in the workplace, the authors concluded that women feel discriminated against in their careers, not only because of persistent gender stereotypes but also due to long working hours. The dimension with the lowest average is innovation culture. These results are also in line with the literature, as

Hofstede (

1991) notes that Portugal is a country with a high aversion to uncertainty, characterized by a low tendency towards innovation. Regarding motivation, the dimensions with the highest average scores are intrinsic motivation and identified motivation, indicating that the participants in this study are motivated in their workplace.

Regarding the differences between participants working in Portugal and those working in Angola, in terms of the variables under study, there are significant differences in supportive culture, innovation culture, introjected motivation, and extrinsic motivation. Participants working in Portugal have a higher perception of a supportive culture and innovation than those working in Angola. On the other hand, participants working in Angola have higher levels of introjected motivation and extrinsic motivation. In a study conducted with nurses in Angola,

Zeng et al. (

2022) concluded that half of nurses are driven by extrinsic motivation in the workplace.

5.1. Limitations and Future Research

Although this study makes a significant contribution to understanding the relationship between organizational culture, perceived organizational support, motivation, and perceived performance, it is essential to acknowledge several limitations that may have influenced the results obtained and that should be considered in future research.

One of the main limitations is the cross-sectional nature of the study, which prevents the establishment of causal relationships between the variables analyzed. Despite the multiple regression, mediation, and moderation models tested, the nature of the design does not allow us to infer the direction of the relationships with certainty. According to

Maxwell and Cole (

2007), longitudinal studies allow causal relationships to be tested with greater rigor. Thus, future research may employ longitudinal or experimental designs to better understand the evolution and effects of these variables over time.

Additionally, the sample used was a convenience sample, primarily composed of participants from Portugal and Angola. Although this geographical diversity brings cultural richness, it does not allow the results to be generalized to other populations. It is suggested that future studies consider representative samples by sector, country, or type of organization and explore the role of national cultural variables, as proposed by

Hofstede et al. (

2010) and

McSweeney (

2002).

Another methodological limitation concerns the exclusive use of self-report questionnaires, which may have introduced common method bias because all variables were collected from the same source and at the same time (

Podsakoff et al., 2003). This type of bias may have artificially inflated the correlations between variables. Future research could employ mixed methods, including qualitative interviews, performance evaluations by supervisors, or objective measures, to triangulate the collected information.

Regarding the variables under study, it is important to note that motivation was considered only as a moderating factor, which may have limited the exploration of its more dynamic role. It would be relevant for future research to analyze the differential and independent effects of each type of motivation (intrinsic, identified, introjected, and extrinsic), for example, by testing parallel mediation models, as suggested by

Gagné and Deci (

2005).

Another limitation of this study is that, when testing the hypotheses formulated, only the country where the participant works was used as a control variable. Finally, it is essential to acknowledge that this study did not account for other relevant organizational variables, such as leadership style, organizational climate, affective commitment, or organizational justice, all of which are widely recognized as influential on employee performance (

Meyer & Allen, 1997;

Colquitt et al., 2001). These variables could be integrated into more comprehensive theoretical models in the future, allowing for a more holistic and ecological analysis of the factors that influence work behavior.

In summary, despite these limitations, this study offers relevant theoretical and empirical contributions, serving as a basis for future research that aims to deepen the understanding of the impact of organizational culture on individual and organizational outcomes through motivational and perceptual mechanisms.

5.2. Practical Implications

The results of this study offer valuable contributions to human resource management practice, with relevance to building organizational cultures that promote employee well-being, engagement, and performance. Evidence suggests that specific dimensions of organizational culture directly influence performance and indirectly through perceived organizational support and motivation, allowing key areas for organizational intervention to be identified.

Firstly, the confirmation that goal culture and rule culture have a positive impact on perceived performance suggests that organizations should reinforce practices of clear goal setting, results orientation, and transparent communication of norms. The application of methodologies such as the Balanced Scorecard (

Kaplan & Norton, 1992) can facilitate alignment between the organization’s strategic objectives and the individual objectives of employees, promoting clarity and focus. In addition, the existence of well-structured and -understood rules can contribute to a sense of security and predictability, which, in turn, favors performance, especially in more formal or hierarchical organizational contexts.

Secondly, the data reveal that a supportive culture is crucial for strengthening the perception of affective organizational support, a factor with a significant impact on motivation and performance. Therefore, organizations should adopt people-centered management practices, such as individualized recognition (

Brun & Dugas, 2008), mentoring programs, transformational leadership actions, and relational competence development in team managers (

Eisenberger & Stinglhamber, 2011). In the Portuguese context, where values such as interpersonal respect and stability are culturally valued (

Hofstede et al., 2010), these practices may have a particularly positive impact.

Additionally, research has shown that the perception of organizational support has a direct influence on performance and serves as a mediating factor in the relationship between organizational culture and performance. This mediating effect indicates that employees tend to be more involved when they perceive that their personal goals are aligned with those of the organization. It is, therefore, essential that organizations encourage the internalization of organizational values through practices such as transparent institutional communication, active participation in decisions, and meaningful projects, as proposed by self-determination theory (

Deci & Ryan, 1985;

Gagné & Deci, 2005).

In the case of organizations in different cultural contexts, such as Angola, it may be necessary to adapt these practices, reinforcing formal structures of recognition and support to fill any perceived gaps. Building a strong organizational culture consistent with local values can be an effective way to increase the sense of belonging and, consequently, organizational performance and commitment.

Finally, these results highlight the importance of human resource managers adopting a strategic and proactive approach to developing organizational culture, treating it not as a static element but as a dynamic management tool capable of enhancing motivation, the perception of support, and, ultimately, employee performance.

5.3. Theoretical Implications

This study offers a relevant theoretical contribution to understanding organizational dynamics by integrating the dimensions of organizational culture, perceived organizational support, motivation, and employee performance into a single conceptual model. This integrated approach enables a more comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms that influence organizational behavior, thereby overcoming the fragmentation observed in parts of the existing literature.

First, the study reinforces the theoretical validity of the competing values structure proposed by

Cameron and Quinn (

2011), demonstrating that different cultural types do not exert a uniform influence on individual variables. The confirmation of the positive effects of goal and rule culture on perceived performance, in contrast to the negative effects of innovation and rule culture on cognitive organizational support, highlights the complexity and contingent nature of organizational culture, as suggested by

Hartnell et al. (

2019). These results point to the need for a critical approach to culture as a multifaceted construct whose effectiveness depends on context and employee perception.

Secondly, this study deepens the understanding of the role of perceived organizational support (POS) as a mediating mechanism in the relationships between organizational culture and performance, supporting the assumptions developed by

Eisenberger et al. (

1986) and

Rhoades and Eisenberger (

2002). The distinction between affective and cognitive support broadens the theoretical understanding of POS, recognizing that different dimensions of support influence employee behavior in different ways. This aspect is particularly relevant given the scarcity of studies that address these dimensions independently.

In addition, the introduction of motivation as a moderating variable helps to consolidate the applicability of self-determination theory (

Ryan & Deci, 2000;

Deci & Ryan, 1985) in the organizational domain. The results obtained suggest the relevance of more autonomous forms of motivation in explaining performance, indicating that the alignment between personal and organizational values enhances the impact of cultural practices and organizational support. This finding corroborates recent studies (

Gagné et al., 2018) that defend the importance of autonomous motivation in promoting sustainable organizational results.

It is also important to highlight the contribution of this study to theoretical advances in the context of interactional and multidimensional analysis. By proposing a relational model that considers mediations and moderations between contextual and individual variables, this study offers a more comprehensive theoretical perspective, aligning with contemporary approaches that advocate for integrative and ecological models in the analysis of organizational behavior (

Ployhart & Moliterno, 2011).

Finally, the results suggest that the variability of effects as a function of sociodemographic characteristics (such as country or sector) may be theoretically relevant. This observation highlights the need to incorporate elements of national or contextualized organizational culture into theoretical models, following the calls of authors such as

Hofstede et al. (

2010) and

McSweeney (

2002), who argue that local cultural values significantly influence the interpretation and impact of organizational practices.

In short, this study not only confirms some fundamental theoretical assumptions but also proposes an expansion of these assumptions by highlighting the complexity of the interactions between culture, support, motivation, and performance and by emphasizing the importance of context in organizational analysis.

6. Conclusions

The main objective of this study was to analyze the influence of organizational culture on the perception of organizational support and its relationship with employee motivation and performance. Based on an integrative conceptual model, different relationships between contextual variables (culture and support) and individual variables (motivation and performance) were tested through mediation and moderation analyses.

The results obtained confirmed the hypotheses formulated, demonstrating that organizational culture influences employees’ perceived performance, directly and indirectly, through the perception of organizational support and the motivation identified. More specifically, it was observed that goal-oriented and rule-oriented cultures have a positive and significant impact on performance. At the same time, the perception of affective organizational support acts as a mediator, and motivation was identified as a moderating and predictive variable.

These results contribute to the organizational literature by integrating constructs that are usually studied in isolation into a single model. From a theoretical perspective, the study reinforces the assumptions of

Cameron and Quinn’s (

2011) competing values framework, self-determination theory (

Ryan & Deci, 2000), and perceived organizational support theory (

Eisenberger et al., 1986). It proposes a relational and contextualized model that reflects the complexity of organizational phenomena.

Methodologically, the study stands out for its articulation of various statistical analyses, including multiple linear regressions, mediations, and moderations, which allow hypothetical causal relationships to be tested with a degree of sophistication appropriate to second-cycle research.

In practical terms, the results highlight the importance of fostering cohesive organizational cultures that focus on clarity of objectives, structure, and human support. Organizations seeking to enhance the performance of their employees should invest in culturally aware leadership, recognition practices, and strategies that reinforce the link between organizational values and the personal values of their professionals.

Despite its theoretical and applied contributions, the study has limitations, including its cross-sectional nature and the use of self-report measures, which may have influenced some of the observed relationships. These limitations pave the way for future research with longitudinal, qualitative approaches and more diverse samples, as well as the exploration of additional variables, such as leadership style, organizational climate, or perceived justice.

In an era of increasing complexity in labor relations, marked by challenges such as hybrid work, cultural diversity, and digitalization, the results of this research are particularly relevant. An integrated understanding of culture, organizational support, and motivation proves to be a promising avenue for promoting sustainable performance and employee well-being, representing a significant contribution to the advancement of research and practice in human resource management.