Purchasing Decisions with Reference Points and Prospect Theory in the Metaverse

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

3. A History of Prospect Theory in the Future

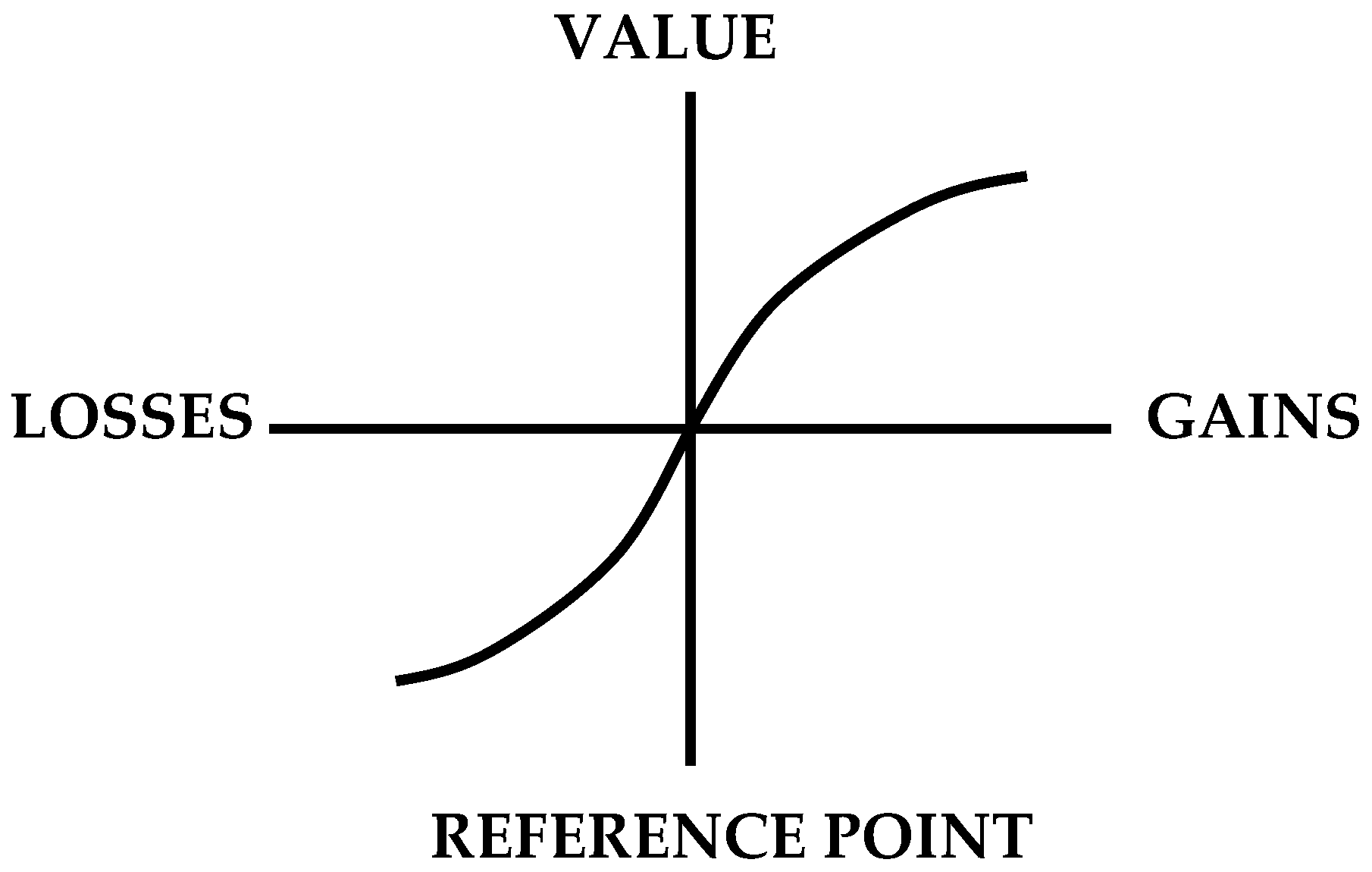

- (i)

- The value part is concave in the domain of gains (<0, x > 0) and convex in the domain of losses (>0, x < 0)

- (ii)

- The value part is loss-averse, steeper in the domain of losses (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979; Thaler, 1985; Kahneman, 1992; Werner & Zank, 2019).

4. Results

- The Standard Version of Virtual Car A:

- -

- Virtual coins are the standard price, which is $15,000.

- -

- The features include basic speed, design, and customization options.

- The Premium Version of Virtual Car B:

- -

- Virtual coins with a standard price of $20,000 are available.

- -

- The features include faster speed, a unique design, and more extensive customization options.

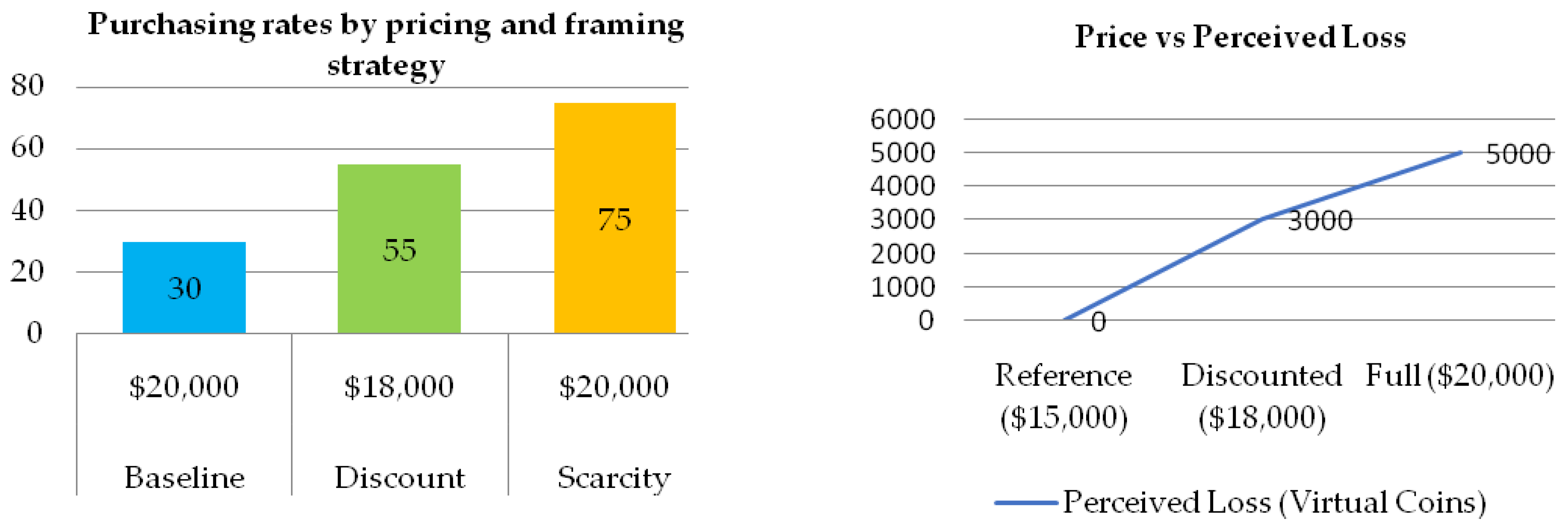

- Car A’s reference point is $15,000:

- -

- The more expensive Virtual Car B is purchased by 30% of consumers at its full price of $20,000.

- -

- The extra $5000 over the reference price is considered a loss.

- Discount Framing:

- -

- Virtual Car B’s price being reduced to $18,000 (a 10% discount) convinces 55% of consumers to purchase it with the discount applied.

- -

- The perception is shifted to a gain by this framing because consumers save $2000 compared to the full price, which reduces the perceived loss from their reference point.

- Scarcity Framing:

- -

- The dealership’s emphasis on Virtual Car B’s limited edition (scarcity framing) triggers loss aversion regarding future availability.

- -

- The premium car is purchased by 75% of consumers at the full price of $20,000 to avoid the perceived loss of missing out.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Practical Implications

6.3. Limitations

6.4. Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Applying Prospect Theory to Metaverse Grocery Shopping

- Gain Frame: They notice that their virtual cart totals $90 due to various promotions and deals. While they feel happy about the savings, prospect theory suggests that the happiness they experience from saving $10 is not as intense as the disappointment they would feel from overpaying.

- Loss Frame: If their total comes to $110 instead of $100, the pain of losing money (spending more than intended) is far more intense than the positive feeling of saving $10, even though the difference is the same.

Appendix A.2. Applying Prospect Theoryto Metaverse Fashion Shoppingin the Metaverse

- Gain Frame: The store offers a complete collection of dresses, shoes, and accessories for $250, which is less than their reference point of $300. However, prospect theory’s diminished sensitivity to gains causes their joy to be less intense than it could have been, despite experiencing a small gain.

- Loss Frame: On the other hand, if that same outfit suddenly costs $350 (more than their reference point), they experience a significant sense of loss. Prospect theory explains that their aversion to loss makes the $50 overspend feel bad to a greater degree than a $50 saving would have made them feel good.

References

- Abdellaoui, M., Bleichrodt, H., & Paraschiv, C. (2007). Loss aversion under prospect theory: A parameter-free measurement. Management Science, 53(10), 1659–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrokwah-Larbi, K. (2024). Transforming metaverse marketing into strategic agility in SMEs through mediating roles of IMT and CI: Theoretical framework and research propositions. Journal of Contemporary Marketing Science, 7(1), 56–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babutsidze, Z. (2007). How do consumers make choices?: A summary of evidence from marketing and psychology (February) [working paper]. United Nations University, Maastricht Economic and Social Research and Training Centre on Innovation and Technology. Available online: https://unu-merit.nl/publications/wppdf/2007/wp2007-005.pdf (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- Babutsidze, Z. (2012). How do consumers make choices? A survey of evidence. Journal of Economic Surveys, 26(4), 752–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, J., Das, R., Alalwan, A. A., Raman, R., & Dwivedi, Y. K. (2024). Informative and peripheral metaverse: Which leads to experience? An investigation from the viewpoint of self-concept. Computers in Human Behavior, 156, 108223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barberis, N. C. (2013). Thirty years of prospect theory in economics: A review and assessment. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 27(1), 173–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkan, R., Danziger, S., Ben-Bashat, G., & Busemeyer, J. R. (2005). Framing reference points: The effect of integration and segregation on dynamic inconsistency. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 18, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beggan, J. K. (1994). The preference for gains in consumer decision making. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 24(16), 1407–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, D. R., & Bucklin, R. E. (1999). The role of internal reference points in the category purchase decision. Journal of Consumer Research, 26(2), 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettman, J. R., Luce, M. F., & Payne, J. W. (1998). Constructive consumer choice processes. Journal of Consumer Research, 25(3), 187–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettman, J. R., & Zins, M. A. (1977). Constructive processes in consumer choice. Journal of Consumer Research, 4, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betts, S. C., & Taran, Z. (2005). Brand as reliability reference point: A test of prospect theory in the used car market. Journal of Academy of Business and Economics, 5(1), 34–38. [Google Scholar]

- Bolton, D., & Madhavaram, S. (2025). Impact of customized price promotions on deal response: The roles of functional impulsivity, promotion frame, emotional arousal, and self-enhancement. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 33(3), 412–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchouicha, R., & Vieider, F. M. (2017). Accommodating stake effects under prospect theory. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 55(1), 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, B., Yaoyuneyong, G., Pollitte, W. A., & Sullivan, P. (2023). Adopting retail technology in crises: Integrating TAM and prospect theory perspectives. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 51(7), 939–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busemeyer, J. R., & Johnson, J. G. (2003). Comparing models of preferential choice: Technical report. 19 December 2008. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/254665050_Comparing_Models_of_Preferential_Choice (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Chen, C.-W. (2024). Utilizing a hybrid approach to identify the importance of factors that influence consumer decision-making behavior in purchasing sustainable products. Sustainability, 16(11), 4432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q., Zhang, X., Liu, S., & Zhu, W. (2024). The inventory bullwhip effect in the online retail supply chain considering the price discount based on different forecasting methods. The Engineering Economist, 69(2), 108–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S., Zhao, J., Xu, H., & Zhu, Z. (2024). When and how does decoy effect work? The roles of salience and risk aversion in the consumer decision-making process. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 63, 101354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T., Wu, X., Wang, B., & Yang, J. (2025). The role of behavioral decision-making in panic buying events during COVID-19: From the perspective of an evolutionary game based on prospect theory. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 82, 104067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.-H., Chuang, S.-C., Lee, C.-F., & Kao, C.-Y. (2023). The influence of price location on reference-price ads. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 41(1), 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernev, A. (2005). Context effects without a context: Attribute balance as a reason for choice. Journal of Consumer Research, 32(2), 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datt, M., Gupta, A., Misra, S. K., & Gupta, M. (2024). Theory of constraints in healthcare: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, 41(6), 1417–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, D. F. (2022). Distributions distract: How distributions on attribute filters and other tools affect consumer judgments. Journal of Consumer Research, 49(6), 1074–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dholakia, U. M., & Simonson, I. (2005). The effect of explicit reference points on consumer choice and online bidding behavior. Marketing Science, 24(2), 206–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emami, A., Taheri, Z., & Zuferi, R. (2024). The interplay between framing effects, cognitive biases, and learning styles in online purchasing decision: Lessons for Iranian enterprising communities. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy, 18(2), 347–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortin, I., & Hlouskova, J. (2024). Prospect theory and asset allocation. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 94, 214–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H., Chong, A. Y. L., & Bao, H. (2024). Metaverse: Literature review, synthesis and future research agenda. Journal of Computer Information Systems, 64(4), 533–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghali, Z., Rather, R. A., & Khan, I. (2024). Investigating metaverse marketing-enabled consumers’ social presence, attachment, engagement and (re) visit intentions. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 77, 103671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldfarb, A., Tucker, C., & Wang, Y. (2022). Conducting research in marketing with quasi-experiments. Journal of Marketing, 86(3), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R., Rathore, B., Biswas, B., Jaiswal, M., & Singh, R. K. (2024). Are we ready for metaverse adoption in the service industry? Theoretically exploring the barriers to successful adoption. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 79, 103882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi, R., Melumad, S., & Park, E. S. (2024). The Metaverse: A new digital frontier for consumer behavior. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 34(1), 142–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajian, A., Daneshgar, S., Sadeghi R, K., Ojha, D., & Katiyar, G. (2024). From theory to practice: Empirical perspectives on the metaverse’s potential. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 201, 123224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, C., Larrick, R. P., & Wu, G. (1999). Goals as reference points. Cognitive Psychology, 38, 79–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, D. (2024). Humanizing metaverse: Psychological involvement and masstige value in retail versus tourism platforms. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 48(2), e13025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Z., Kang, H., Liu, J., & Sun, A. (2024). A new marketing strategy in the digital age: Meta-universe marketing. In Addressing global challenges-exploring socio-cultural dynamics and sustainable solutions in a changing world (pp. 573–580). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman, D. (1992). Reference points, anchors norms and mixed feelings. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 51, 296–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D. (2003). Maps of bounded rationality: Psychology for behavioral economics. American Economic Review, 93(5), 1449–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47, 263–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, J., Mogaji, E., Paliwal, M., Jha, S., Agarwal, S., & Mogaji, S. A. (2024). Consumer behavior in the metaverse. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 23(4), 1720–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinley, T. L., Conrad, R., & Brown, G. (2000). Personal vs. non-personal sources of information used in the purchase of men’s apparel. Journal of Consumer Studies & Home Economics, 24(1), 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivetz, R., Netzer, O., & Srinivasan, V. (2004). Alternative models for capturing the compromise effect. Journal of Marketing Research, 41(3), 237–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, N. M., & Oglethorpe, J. E. (1987). Cognitive reference points in consumer decision making. Journal of Consumer Research, 14(1), 183–187. [Google Scholar]

- Koh, D. (2024). Loss aversion distribution: The science behind loss aversion exhibited by sellers of perishable good. Journal of Behavioral Data Science, 4(1), 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauterbach, B., Mugerman, Y., & Shemesh, J. (2024). Prospect theory in M&A: Do historical purchase prices affect merger offer premiums and announcement returns? Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance, 42, 100931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O’Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5(1), 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, G., Lin, M. S., & Song, H. (2024). An assessment of prospect theory in tourism decision-making research. Journal of Travel Research, 63(2), 275–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H., Meng-Lewis, Y., Ibrahim, F., & Zhu, X. (2021). Superfoods, super healthy: Myth or reality? Examining consumers’ repurchase and WOM intention regarding superfoods: A theory of consumption values perspective. Journal of Business Research, 137, 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S., Gao, L., Chen, J., & Yan, J. (2024). Single-neuron analysis of axon arbors reveals distinct presynaptic organizations between feedforward and feedback projections. Cell Reports, 43(1), 113590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mak, S., & Thomas, A. (2022). An introduction to scoping reviews. Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 14(5), 561–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manthiou, A., Luong, V. H., Ayadi, K., & Klaus, P. (2024). The metaverse experience: A big data approach to virtual service consumption. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, R., Huan, T.-C., Xu, Y., & Nam, I. (2011). Extending prospect theory cross-culturally by examining switching behavior in consumer and business-to-business contexts. Journal of Business Research, 64(8), 871–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mead, N. L., & Williams, L. E. (2022). The pursuit of meaning and the preference for less expensive options. Journal of Consumer Research, 49(5), 741–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meunier, L., & Ohadi, S. (2023). When are two portfolios better than one? A prospect theory approach. Theory and Decision, 94(3), 503–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustapha, F. A., Ertz, M., & Ouerghemmi, C. (2024). Virtual tasting in the metaverse: Technological advances and consumer behavior impacts. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction, 8(10), 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z., Peters, M. D. J., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(1), 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munro, A., & Sugden, R. (2003). On the theory of reference-dependent preferences. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 50(4), 407–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussweiler, T. (2003). Comparison processes in social judgment: Mechanisms and consequences. Psychological Review, 110(3), 472–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolau, J. L., Shin, H., Kim, B., & O’Connell, J. F. (2023). The Impact of loss aversion and diminishing sensitivity on airline revenue: Price sensitivity in cabin classes. Journal of Travel Research, 62(3), 685–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nittala, R., & Moturu, V. R. (2023). Role of pro-environmental post-purchase behaviour in green consumer behaviour. Vilakshan—XIMB Journal of Management, 20(1), 82–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obukhovich, S., Sipilä, J., & Tarkiainen, A. (2024). Post-purchase effects of impulse buying: A review and research agenda. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 23(3), 1512–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, P. K., Pandey, P. K., Mahajan, S., Behera, J., & Tausif, M. R. (2024). Mitigating negative externalities in the metaverse: Challenges and strategies. In Green metaverse for greener economies (pp. 247–269). CRC Press. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J., & Kim, N. (2023). Examining self-congruence between user and avatar in purchasing behavior from the metaverse to the real world. Journal of Global Fashion Marketing, 15(1), 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, J. W., Bettman, J. R., & Johnson, E. J. (1992). Behavioral decision research: A constructive processing perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 43, 87–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelka, S., Bosch, A., Chappin, E. J., Liesenhoff, F., Kühnbach, M., & de Vries, L. (2024). To charge or not to charge? Using prospect theory to model the tradeoffs of electric vehicle users. Sustainability Science, 19, 793–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, N. (2004). Metacognitive experiences in consumer judgment and decision making. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 14(4), 332–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A. M., Eisenkraft, N., Bettman, J. R., & Chartrand, T. L. (2016). “Paper or plastic?”: How we pay influences post-transaction connection. Journal of Consumer Research, 42(5), 688–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P., Ueno, A., Dennis, C., & Turan, C. P. (2023). Emerging digital technologies and consumer decision-making in retail sector: Towards an integrative conceptual framework. Computers in Human Behavior, 148, 107913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, J. N., Newman, B. I., & Gross, B. L. (1991). Why we buy what we buy: A theory of consumption values. Journal of Business Research, 22(2), 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonson, I. (1989). Choice based on reasons: The case of attraction and compromise effects. Journal of Consumer Research, 16(2), 158–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonson, I., & Tversky, A. (1992). Choice in context: Tradeoff contrast and extremeness aversion. Journal of Marketing Research, 29(3), 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivakumar, K., & Feng, C. (2019). Patterns of product improvements and customer response. Journal of Business Research, 104, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridhar, S., Lamberton, C., Marinova, D., & Swaminathan, V. (2022). JM: Promoting catalysis in marketing scholarship. Journal of Marketing, 87(1), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stommel, E., Gottschalck, N., Hack, A., Eddleston, K. A., Kellermanns, F., & Kraiczy, N. (2024). What is your reference point? How price volatility and organizational context affect the reference points of family and nonfamily managers. Small Business Economics, 63(2), 805–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, M. U. (2025). Revolutionizing retail: Enhancing customer experiences with the metaverse. In M. A. Gonçalves Rodrigues, M. A. Carvalho, & J. F. Monteiro Pratas (Eds.), Cases on metaverse and consumer experiences (pp. 175–202). IGI Global Scientific Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarnanidis, T. (2023). Understanding reference points to make purchase decisions: Overview, phases, and time-features. Marketing Science & Inspirations, 18(4), 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarnanidis, T. (Ed.). (2024). Consumer experience and decision-making in the metaverse. IGI Globa. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarnanidis, T., & Manaf, A. H. (2024). Research notes on the future of marketing and consumer insights. In T. Tarnanidis, & N. Sklavounos (Eds.), New trends in marketing and consumer science (pp. 324–336). IGI Global. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarnanidis, T., Owusu-Frimpong, N., & Marciniak, R. (2010). Consumer choice: Between explicit and implicit reference points. The Marketing Review, 10(3), 269–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarnanidis, T., Owusu-Frimpong, N., & Nwankwo, S. (2020). How consumers’ make purchase decisions with the use of reference points. Journal of Marketing and Consumer Research, 68, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarnanidis, T., Owusu-Frimpong, N., Nwankwo, S., & Omar, M. (2015). Why we buy? Modeling consumer selection of referents. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 22(1), 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarnanidis, T., Papathanasiou, J., Osei-Frimpong, K., & Owusu-Frimpong, N. (2024). How young consumers are influenced by the valence of positive and negative frames: A cross-cultural perspective. International Journal of Information and Decision Sciences, 16(2), 109–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarnanidis, T. K., & Sklavounos, N. (Eds.). (2024). New trends in marketing and consumer science. IGI Global. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaler, R. H. (1985). Mental accounting and consumer choice. Marketing Science, 4(3), 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tversky, A. (1972). Elimination by aspects: A theory of choice. Psychological Review, 79(4), 281–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1986). Rational choice and the framing of decisions. Journal of Business, 59(4), 251–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1991). Loss aversion in riskless choice: A reference-dependent model. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 106, 1039–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tversky, A., & Simonson, I. (1993). Context dependent preferences. Management Science, 39, 1179–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Heerde, H. J., Moorman, C., Moreau, C. P., & Palmatier, R. W. (2021). Reality check: Infusing ecological value into academic marketing research. Journal of Marketing, 85(2), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrtana, D., & Krizanova, A. (2023). The power of emotional advertising appeals: Examining their influence on consumer purchasing behavior and brand–customer relationship. Sustainability, 15(18), 13337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, S., & Etkin, J. (2024). Range goals as dual reference points. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 184, 104340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., Wang, T., Shi, Y., Xu, D., Chen, Y., & Wu, J. (2022). Metaverse, SED model, and new theory of value. Complexity, 2022(1), 4771516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L., Feng, X., & Zang, L. (2024). Does risk perception influence individual investors’ crowdfunding investment decision-making behavior in the metaverse tourism? Finance Research Letters, 62, 105168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P., Sun, L., Zhang, L., & Niraj, R. (2021). Reference points in consumer choice models: A review and future research agenda. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 45(5), 985–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, K. M., & Zank, H. (2019). A revealed reference point for prospect theory. Economic Theory, 67(4), 731–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, K. S., & Lam, S. S. K. (1997). Measuring service quality: A test-retest reliability investigation of servqual. Market Research Society Journal, 39(2), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W., Wang, X., & Xia, Q. (2024). Why leave items in the shopping cart? The impact of consumer filtering behavior. Information Processing & Management, 61(6), 103854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X., Li, J., Si, H., & Wu, P. (2024). Attention marketing in fragmented entertainment: How advertising embedding influences purchase decision in short-form video apps. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 76, 103572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors/Publications | Prospect Theory | Metaverse Example | Primary Conclusions | Practical Implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) Reference points | People evaluate outcomes relative to a reference point (e.g., the standard price of an item). The perception of a change as a gain or a loss is influenced by this reference point. | A shopper in the metaverse buys a carton of milk every day for $2. They may perceive a gain based on their reference point of $2 if they log in and observe that the price has gone down to $1.50. However, if the price increases to $2.50, they will experience a loss, even though the monetary change is only $0.50 either way. | In the metaverse, shoppers compare prices to their internal reference points, reacting with greater force when faced with perceived losses than gains. | Retailers in the metaverse have the option to influence shopper behavior by utilizing reference pricing data. |

| (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979), JSTOR; (Kahneman, 2003), PBE (T. Tarnanidis et al., 2010), TMR (Barberis, 2013), JEP (T. Tarnanidis et al., 2015), JRCS (T. Tarnanidis, 2023), MSI (T. Tarnanidis, 2024), IGI | ||||

| (b) Loss Aversion | The idea that people experience losses more acutely than gains is known as loss aversion. In metaverse shopping, this principle can be utilized in multiple ways. | Shoppers can buy a discounted digital version of their daily coffee at a virtual store in the metaverse. If the shopper does not take advantage of the offer within an hour, the price will return to normal. | It is possible to encourage quicker decision-making by pointing out potential losses (missed deals, time-limited discounts) | The pain of losing this discount (perceived loss) will exceed the joy of gaining it, according to prospect theory. |

| (Tversky & Kahneman, 1991). QJE (Abdellaoui et al., 2007), MS (Marshall et al., 2011)JBR (Sivakumar & Feng, 2019), JBR (H. Liu et al., 2021), JBR (Lauterbach et al., 2024), JBEF | ||||

| (c) Framing Effects | The way a decision or choice is presented (framed) has an impact on shoppers’ reactions in the metaverse. Different behaviors can be caused by the same outcome being framed as either a gain or a loss. |

| Promoting losses (Don’t miss) is more effective than promoting gains (Save now). People tend to be more sensitive to the fear of losing a deal than to the satisfaction of obtaining one. | Using negative framing (highlighting potential loss) will be more effective in persuading shoppers to take action. |

| (Tversky, 1972), PR (Tversky & Kahneman, 1986). JB (Simonson & Tversky, 1992), JMR (Bolton & Madhavaram, 2025), JMTP (Wallace & Etkin, 2024), ORBHDP (T. Tarnanidis et al., 2024), IJIDS (Emami et al., 2024), JEC | ||||

| (d) Diminishing Sensitivity | The psychological impact of both gains and losses decreases with the increase in magnitude. | When a metaverse shopper saves $2 on a $10 item, they feel a stronger sense of satisfaction than when they save $2 on a $100 item, which feels insignificant. On the other hand, a $2 price increase makes a low-cost item much more unpleasant to deal with. | The emotional impact of small price changes on low-cost items is greater, so frequent micro-discounts may lead to more purchases. | Small changes are felt more strongly by people when the amounts are small. |

| (Simonson, 1989), JCR (Kahneman, 1992), OBHDP (Kivetz et al., 2004), JMR (P. Wang et al., 2021), FRL (Nicolau et al., 2023), JTR | ||||

| (e) Mental Accounting | Money is classified into various “accounts” by individuals, such as money for groceries or entertainment. Different spending behaviors may result from shoppers treating the virtual and realworld separately in the metaverse. | The virtual wallet (which holds cryptocurrency or in-game currency) may be treated differently by shoppers in the metaverse than their real-world bank account. Virtual currency may offer shoppers more comfort when making impulsive purchases because they can mentally separate it from their actual money, even though the value remains the same. | The treatment of virtual currency differs from real money, resulting in more impulsive spending on daily shopping items. | Retailers can encourage shoppers to spend more freely in the metaverse shopping experience by integrating virtual currencies or reward points. |

| (Tversky & Simonson, 1993), MS (Chernev, 2005), JCR (Van Heerde et al., 2021), JM (J. Wang et al., 2022), Complexity (Meunier & Ohadi, 2023), TAD (L. Wang et al., 2024), JCS (Fortin & Hlouskova, 2024), QREF (T. Chen et al., 2025), JRCS |

| Prospect Theory Characteristics | Consumer Reference Points’ Implications |

|---|---|

| Value Function: Prospect theory posits a value function that explains how people perceive gains and losses. Those who are faced with gains tend to be risk-averse, while those who are faced with losses tend to be risk-seeking. | Gains: Consumer reference points contribute to defining what individuals consider gains or losses. For example, getting a discount on a product might be perceived as a gain, while paying a higher-than-expected price might be perceived as a loss. |

| Endowment Effect: The endowment effect, a psychological phenomenon where people tend to ascribe higher value to things merely because they own them, can be explained by prospect theory. | Ownership: Consumer reference points are often tied to ownership. Once someone owns a product, that ownership becomes a reference point, and the perceived value of the item increases. |

| Loss Aversion: Loss aversion is a key concept in prospect theory, stating that losses typically have a greater impact on decision-making than equivalent gains. | Losses: Consumer reference points influence what individuals perceive as losses. For instance, if a consumer expected a product to be available at a certain price, paying more than that reference point can be perceived as a loss. |

| Anchoring: Anchoring is a cognitive bias in which individuals rely too heavily on the first piece of information encountered when making decisions. | Anchoring: Consumer reference points can act as anchors. For instance, an initial price tag or an advertised “original” price can serve as a reference point, influencing consumers’ perceptions of value and willingness to pay. |

| Decision Stages (1–5) | Practical Implications | Consumer Implications | Implications for Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Problem Recognition | The recognition of a problem or a need is often what kicks off the decision-making process. | Consumers may recognize a difference between their present state and their desired state (Schwarz, 2004; Yin et al., 2024). | Past experiences, recommendations, or exposure to marketing messages can trigger reference points at this stage. |

| Information Search | Consumers begin an information search once they recognize the problem. | During this stage, consumers are actively seeking information about potential solutions (Sharma et al., 2023; T. Tarnanidis, 2023; T. Tarnanidis & Manaf, 2024). | Referencing points are used by consumers when comparing different products or services. They may rely on personal experiences, word of mouth, reviews, and brand reputation as reference points during the information search. |

| Evaluation of Alternatives | Consumers evaluate the available alternatives using their reference points, which align with their preferences and criteria. | Consumers can narrow down options by filtering and prioritizing options with reference points (Davis, 2022; T. Tarnanidis et al., 2020). | During this stage, consideration is given to factors such as price, quality, brand reputation, features, and reviews. |

| Purchase Decision | The final decision made during the decision-making process is the buy decision. | The chosen product or service satisfies the customer’s perceived value and fulfills their expectations based on the established reference criteria (Mead & Williams, 2022; Wu et al., 2024; T. Tarnanidis et al., 2015). | The pros and cons of the alternatives have been weighed by consumers, taking into account their reference points. |

| Post-Purchase Evaluation | Upon making a purchase, consumers have the option to evaluate their satisfaction with the product or service. | Positive reference points for the chosen brand are strengthened when the experience is positive. In the event of a negative outcome, it could alter or create new reference points for future decisions (Obukhovich et al., 2024; Nittala & Moturu, 2023) | This evaluation plays a role in creating future reference points. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tarnanidis, T.; Owusu-Frimpong, N.; Sousa, B.B.; Manda, V.K.; Vlachopoulou, M. Purchasing Decisions with Reference Points and Prospect Theory in the Metaverse. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 287. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15080287

Tarnanidis T, Owusu-Frimpong N, Sousa BB, Manda VK, Vlachopoulou M. Purchasing Decisions with Reference Points and Prospect Theory in the Metaverse. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(8):287. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15080287

Chicago/Turabian StyleTarnanidis, Theodore, Nana Owusu-Frimpong, Bruno Barbosa Sousa, Vijaya Kittu Manda, and Maro Vlachopoulou. 2025. "Purchasing Decisions with Reference Points and Prospect Theory in the Metaverse" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 8: 287. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15080287

APA StyleTarnanidis, T., Owusu-Frimpong, N., Sousa, B. B., Manda, V. K., & Vlachopoulou, M. (2025). Purchasing Decisions with Reference Points and Prospect Theory in the Metaverse. Administrative Sciences, 15(8), 287. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15080287