From Green Culture to Innovation: How Internal Marketing Drives Sustainable Performance in Hospitality

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Formulation

2.1. Internal Green Marketing and Pro-Environmental Behavior

2.2. Internal Green Marketing and Internal Green Value

2.3. Internal Green Marketing and Innovative Performance

2.4. Internal Green Value and Innovative Performance

2.5. Pro-Environmental Behavior (PEB) and Innovative Performance

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Scale Development

3.2. Sampling

3.3. Data Analysis Techniques

4. Results

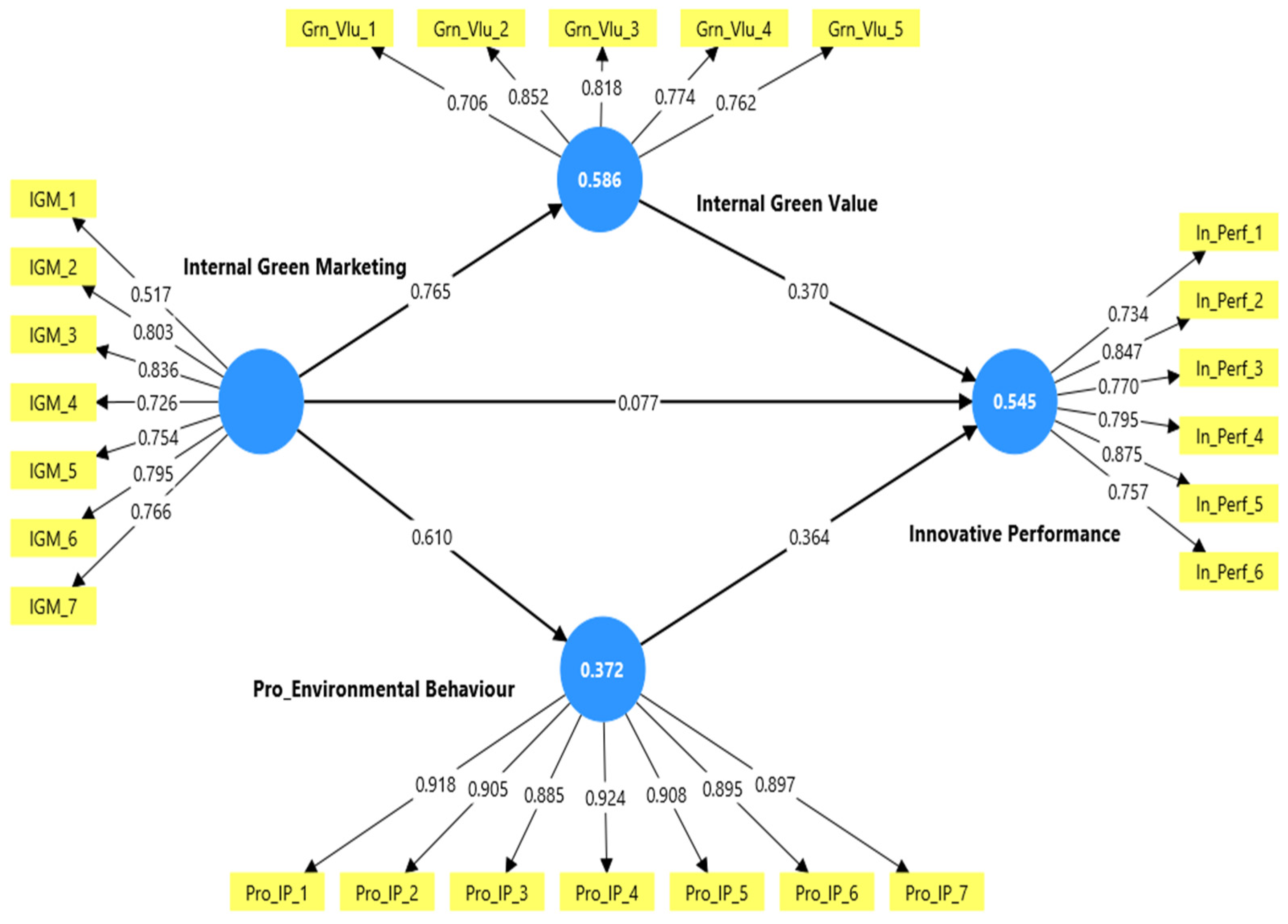

4.1. Stage One: Measurement Model Results

4.2. Stage Two: Structural Model Results and Hypothesis Evaluation

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

7. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adams, R., Jeanrenaud, S., Bessant, J., Denyer, D., & Overy, P. (2016). Sustainability-oriented innovation: A systematic review. International Journal of Management Reviews, 18, 180–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, J., Yadav, M., & Sergio, R. P. (2023). Green Leadership and pro-environmental behaviour: A moderated mediation model with rewards, self-efficacy and training. International Journal of Ethics and Systems, 39, 481–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akterujjaman, S. M., Blaak, L., Ali, M. I., & Nijhof, A. (2022). Organizational citizenship behavior for the environment: A management perspective (Vol. 30). Emerald Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Alherimi, N., Marva, Z., Hamarsheh, K., & Alzaatreh, A. (2024). Employees’ pro-environmental behavior in an organization: A case study in the UAE. Scientific Reports, 14, 15371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alipour, H., Safaeimanesh, F., & Soosan, A. (2019). Investigating sustainable practices in hotel industry-from employees’ perspec-tive: Evidence from a mediterranean island. Sustainability, 11, 6556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azazz, A. M., & Elshaer, I. A. (2022). Amid COVID-19 pandemic, entrepreneurial resilience and creative performance with the me-diating role of institutional orientation: A quantitative investigation using structural equation modeling. Mathematics, 10, 2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J., Wright, M., & Ketchen, D. J. (2001). The resource-based view of the firm: Ten years after 1991. Journal of Management, 27, 625–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P. (2017). Exchange and power in social life. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Boiral, O., & Paillé, P. (2012). Organizational citizenship behaviour for the environment: Measurement and validation. Journal of Business Ethics, 109(4), 431–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borah, P. S., Dogbe, C. S. K., Pomegbe, W. W. K., Bamfo, B. A., & Hornuvo, L. K. G. M. O. (2023). Green innovation capability, green knowledge acquisition and green brand positioning as determinants of new product success. European Journal of Innovation Management, 26, 364–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E. S. (2014). Green marketing: Hotel customers’ perspective. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 31, 915–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W. W. (2010). How to write up and report PLS analyses. In V. Esposito Vinzi, W. W. Chin, J. Henseler, & H. Wang (Eds.), Handbook of partial least squares (pp. 655–690). Springer Berlin Heidelberg. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, C.-J. (2014). Hotels’ environmental policies and employee personal environmental beliefs: Interactions and outcomes. Tourism Management, 40, 436–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirović Bajrami, D., Cimbaljević, M., Petrović, M. D., Radovanović, M. M., & Gajić, T. (2025). Internal marketing and employees’ personality traits toward green innovative hospitality. Tourism Review, 80, 710–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewi, K. I. E., Bagiastuti, N. K., Sutama, I. K., & Sarja, N. L. A. K. Y. (2022). Implementation of eco-friendly behavior by front office employees to support green hotel at The Ritz-Carlton Bali. International Journal of Green Tourism Research and Applications, 4, 68–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaer, I. A., Azazz, A. M. S., Alshebami, A. S., Abdulaziz, T. A., Mansour, M. A., & Fayyad, S. (2024). Internal green marketing ori-entation and business performance: The role of employee environmental commitment and green organizational identity. In-Novative Research Publishing, 7, 211–225. [Google Scholar]

- Elshaer, I. A., Sobaih, A. E. E., Aliedan, M., & Azazz, A. M. (2021). The effect of green human resource management on environ-mental performance in small tourism enterprises: Mediating role of pro-environmental behaviors. Sustainability, 13, 1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frese, M., Fay, D., Hilburger, T., Leng, K., & Tag, A. (1997). The concept of personal initiative: Operationalization, reliability and validity in two german samples. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 70, 139–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galal, H. M., Abu Elella, R. M. E., & Ragib, F. N. (2024). Understanding the antecedents and outcomes of green organizational culture: Evidence from an emerging country perspective [Preprint]. SSRN. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5018030 (accessed on 1 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Gold, A. H., Malhotra, A., & Segars, A. H. (2001). Knowledge management: An Organizational capabilities perspective. Journal of Management Information Systems, 18(1), 185–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, J. C. F., Dorion, E. C. H., & Severo, E. A. (2020). Antecedents, mediators and consequences of sustainable operations: A framework for analysis of the manufacturing industry. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 27, 2189–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürlek, M., & Tuna, M. (2018). Reinforcing competitive advantage through green organizational culture and green innovation. The Service Industries Journal, 38, 467–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 19(2), 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., & Mena, J. A. (2012). An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 40(3), 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Matthews, L. M., Matthews, R. L., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: Updated guidelines on which method to use. International Journal of Multivariate Data Analysis, 1(2), 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hays, D., & Ozretic-Došen. (2014). \DJur\djana greening hotels-building green values into hotel services (Vol. 20, pp. 85–102). Sveučilište u Rijeci, Fakultet za menadžment u turizmu i ugostiteljstvu. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1998). Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods, 3(4), 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, Q. (2020). The era of environmental sustainability: Ensuring that sustainability stands on human resource management. Global Business Review, 21, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. J., Kim, W. G., Choi, H.-M., & Phetvaroon, K. (2019). The effect of green human resource management on hotel employees’ eco-friendly behavior and environmental performance. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 76, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leguina, A. (2015). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 38, 220–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R. (2015). A holistic perspective on corporate sustainability drivers. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 22, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manganari, E. E., Dimara, E., & Theotokis, A. (2016). Greening the lodging industry: Current status, trends and perspectives for green value. Current Issues in Tourism, 19, 223–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercade Mele, P., Molina Gomez, J., & Garay, L. (2019). To green or not to green: The influence of green marketing on consumer behaviour in the hotel industry. Sustainability, 11, 4623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwokah, N. G., & Briggs, J. T. (2017). Internal marketing and marketing effectiveness of hotel industry in rivers state. Journal of Human Resource and Sustainability Studies, 5, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paillé, P., Chen, Y., Boiral, O., & Jin, J. (2014). The impact of human resource management on environmental performance: An employee-level study. Journal Business Ethics, 121, 451–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadas, K.-K., Avlonitis, G. J., Carrigan, M., & Piha, L. (2019). The Interplay of strategic and internal green marketing orientation on competitive advantage (Vol. 104). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P. M., Podsakoff, N. P., Williams, L. J., Huang, C., & Yang, J. (2024). Common method bias: It’s bad, it’s complex, it’s widespread, and it’s not easy to fix. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 11(1), 17–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renwick, D. W. S., Redman, T., & Maguire, S. (2013). Green human resource management: A review and research Agenda*. International Journal of Management Reviews, 15, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, J. L., & Barling, J. (2017). Toward a new measure of organizational environmental citizenship behavior. Journal of Business Research, 75, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schein, E. H. (2010). Organizational culture and leadership (Vol. 2). John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S. K., Del Giudice, M., Chierici, R., & Graziano, D. (2020). Green innovation and environmental performance: The role of green transformational leadership and green human resource management. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 150, 119762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taneja, A., Goyal, V., & Malik, K. (2023). SUSTAINABILITY-ORIENTED innovations—Enhancing factors and consequences. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 30, 2747–2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tardin, M. G., Perin, M. G., Simões, C., & Braga, L. D. (2024). Organizational sustainability orientation: A review. Organization & Environment, 37, 298–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenenhaus, M., Esposito Vinzi, V., Chatelin, Y.-M., & Lauro, C. (2005). PLS path modeling. Computational Statistics & Data Analysis, 48(1), 159–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G., & Netemeyer, R. G. (2004). Salesperson creative performance: Conceptualization, measurement, and nomological validity. Journal of Business Research, 57, 805–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesselink, R., Blok, V., Leur, S., Lans, T., & Dentoni, D. (2015). Individual competencies for managers engaged in corporate sustainable management practices. Elsevier, 106, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L. J., & Anderson, S. E. (1991). Job satisfaction and organizational commitment as predictors of organizational citizenship and in-role behaviors. Journal of Management, 17, 601–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B., Gao, X., Cai, W., & Jiang, L. (2022). How environmental leadership boosts employees’ green innovation behavior? a moderated mediation model. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 689671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, T., Gao, C., Chen, F., Zhang, L., & Li, M. (2022). Can empowering leadership promote employees’ pro-environmental be-havior? empirical analysis based on psychological distance. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 774561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Duan, C., Zhang, J., & Akhtar, M. N. (2024). Positive leadership and employees’ pro-environmental behavior: A meta-analysis. Current Psychology, 43, 31405–31415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Items | λ | VIF | R2 | Q2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IGM (a = 0.865, CR = 0.898, AVE = 0.561) | -- | -- | ||

| IGM_1 | 0.517 | 1.469 | ||

| IGM_2 | 0.803 | 2.394 | ||

| IGM_3 | 0.836 | 2.581 | ||

| IGM_4 | 0.726 | 1.883 | ||

| IGM_5 | 0.754 | 1.982 | ||

| IGM_6 | 0.795 | 2.087 | ||

| IGM_7 | 0.766 | 1.939 | ||

| IP (a = 0.885, CR = 0.913, AVE = 0.637) | 0.545 | 0.333 | ||

| In_Perf_1 | 0.734 | 2.276 | ||

| In_Perf_2 | 0.847 | 4.165 | ||

| In_Perf_3 | 0.770 | 1.899 | ||

| In_Perf_4 | 0.795 | 2.269 | ||

| In_Perf_5 | 0.875 | 3.703 | ||

| In_Perf_6 | 0.757 | 2.235 | ||

| IGV (a = 0.842, CR = 0.888, AVE = 0.615) | 0.586 | 0.583 | ||

| Grn_Vlu_1 | 0.706 | 1.551 | ||

| Grn_Vlu_2 | 0.852 | 2.405 | ||

| Grn_Vlu_3 | 0.818 | 2.164 | ||

| Grn_Vlu_4 | 0.774 | 1.928 | ||

| Grn_Vlu_5 | 0.762 | 1.790 | ||

| PEB (a = 0.963, CR = 0.969, AVE = 0.819) | 0.372 | 0.368 | ||

| Pro_IP_1 | 0.918 | 4.536 | ||

| Pro_IP_2 | 0.905 | 4.444 | ||

| Pro_IP_3 | 0.885 | 3.693 | ||

| Pro_IP_4 | 0.924 | 4.236 | ||

| Pro_IP_5 | 0.908 | 4.109 | ||

| Pro_IP_6 | 0.895 | 4.418 | ||

| Pro_IP_7 | 0.897 | 4.157 |

| IP | IGM | IGV | PEB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grn_Vlu_1 | 0.481 | 0.593 | 0.706 | 0.463 |

| Grn_Vlu_2 | 0.609 | 0.682 | 0.852 | 0.538 |

| Grn_Vlu_3 | 0.530 | 0.598 | 0.818 | 0.619 |

| Grn_Vlu_4 | 0.483 | 0.580 | 0.774 | 0.572 |

| Grn_Vlu_5 | 0.583 | 0.538 | 0.762 | 0.605 |

| IGM_1 | 0.367 | 0.517 | 0.389 | 0.329 |

| IGM_2 | 0.435 | 0.803 | 0.642 | 0.460 |

| IGM_3 | 0.455 | 0.836 | 0.603 | 0.414 |

| IGM_4 | 0.389 | 0.726 | 0.580 | 0.465 |

| IGM_5 | 0.472 | 0.754 | 0.585 | 0.554 |

| IGM_6 | 0.412 | 0.795 | 0.620 | 0.503 |

| IGM_7 | 0.512 | 0.766 | 0.555 | 0.444 |

| In_Perf_1 | 0.734 | 0.504 | 0.517 | 0.497 |

| In_Perf_2 | 0.847 | 0.537 | 0.526 | 0.522 |

| In_Perf_3 | 0.770 | 0.534 | 0.524 | 0.576 |

| In_Perf_4 | 0.795 | 0.341 | 0.580 | 0.563 |

| In_Perf_5 | 0.875 | 0.487 | 0.532 | 0.500 |

| In_Perf_6 | 0.757 | 0.387 | 0.601 | 0.557 |

| Pro_IP_1 | 0.635 | 0.612 | 0.677 | 0.918 |

| Pro_IP_2 | 0.632 | 0.645 | 0.715 | 0.905 |

| Pro_IP_3 | 0.574 | 0.539 | 0.590 | 0.885 |

| Pro_IP_4 | 0.620 | 0.521 | 0.638 | 0.924 |

| Pro_IP_5 | 0.591 | 0.554 | 0.638 | 0.908 |

| Pro_IP_6 | 0.597 | 0.502 | 0.629 | 0.895 |

| Pro_IP_7 | 0.618 | 0.470 | 0.610 | 0.897 |

| IP | IGM | IGV | PEB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IP | 0.798 | |||

| IGM | 0.582 | 0.799 | ||

| IGV | 0.688 | 0.765 | 0.784 | |

| PEB | 0.674 | 0.610 | 0.712 | 0.905 |

| IP | IGM | IGV | PEB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IP | ||||

| IGM | 0.670 | |||

| IGV | 0.793 | 0.894 | ||

| PEB | 0.728 | 0.664 | 0.791 |

| β | T Statistics | p Values | Evaluation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internal Green Marketing -> Pro-environmental Behavior | 0.610 | 19.179 | 0.000 | H1: Accepted |

| Internal Green Marketing -> Internal Green Value | 0.765 | 28.307 | 0.000 | H2: Accepted |

| Internal Green Marketing -> Innovative Performance | 0.077 | 1.354 | 0.176 | H3: Rejected |

| Pro-environmental Behavior -> Innovative Performance | 0.364 | 6.033 | 0.000 | H4: Accepted |

| Internal Green Value -> Innovative Performance | 0.370 | 5.623 | 0.000 | H5: Accepted |

| Indirect effects | ||||

| Internal Green Marketing -> Internal Green Value -> Innovative Performance | 0.283 | 5.402 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| Internal Green Marketing -> Pro-environmental Behavior -> Innovative Performance | 0.222 | 5.945 | 0.000 | Accepted |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Elshaer, I.A.; Kooli, C.; Azazz, A.M.S. From Green Culture to Innovation: How Internal Marketing Drives Sustainable Performance in Hospitality. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 286. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15080286

Elshaer IA, Kooli C, Azazz AMS. From Green Culture to Innovation: How Internal Marketing Drives Sustainable Performance in Hospitality. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(8):286. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15080286

Chicago/Turabian StyleElshaer, Ibrahim A., Chokri Kooli, and Alaa M. S. Azazz. 2025. "From Green Culture to Innovation: How Internal Marketing Drives Sustainable Performance in Hospitality" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 8: 286. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15080286

APA StyleElshaer, I. A., Kooli, C., & Azazz, A. M. S. (2025). From Green Culture to Innovation: How Internal Marketing Drives Sustainable Performance in Hospitality. Administrative Sciences, 15(8), 286. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15080286