Demographic Capital and the Conditional Validity of SERVPERF: Rethinking Tourist Satisfaction Models in an Emerging Market Destination

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Tourist Satisfaction in the Experience Economy

2.2. Destination Competitiveness

2.3. Measuring Service Quality and Satisfaction in Emerging Destinations

2.4. Demographic Moderators of Tourist Behavior

2.5. Demographic Capital: Conceptual Foundations

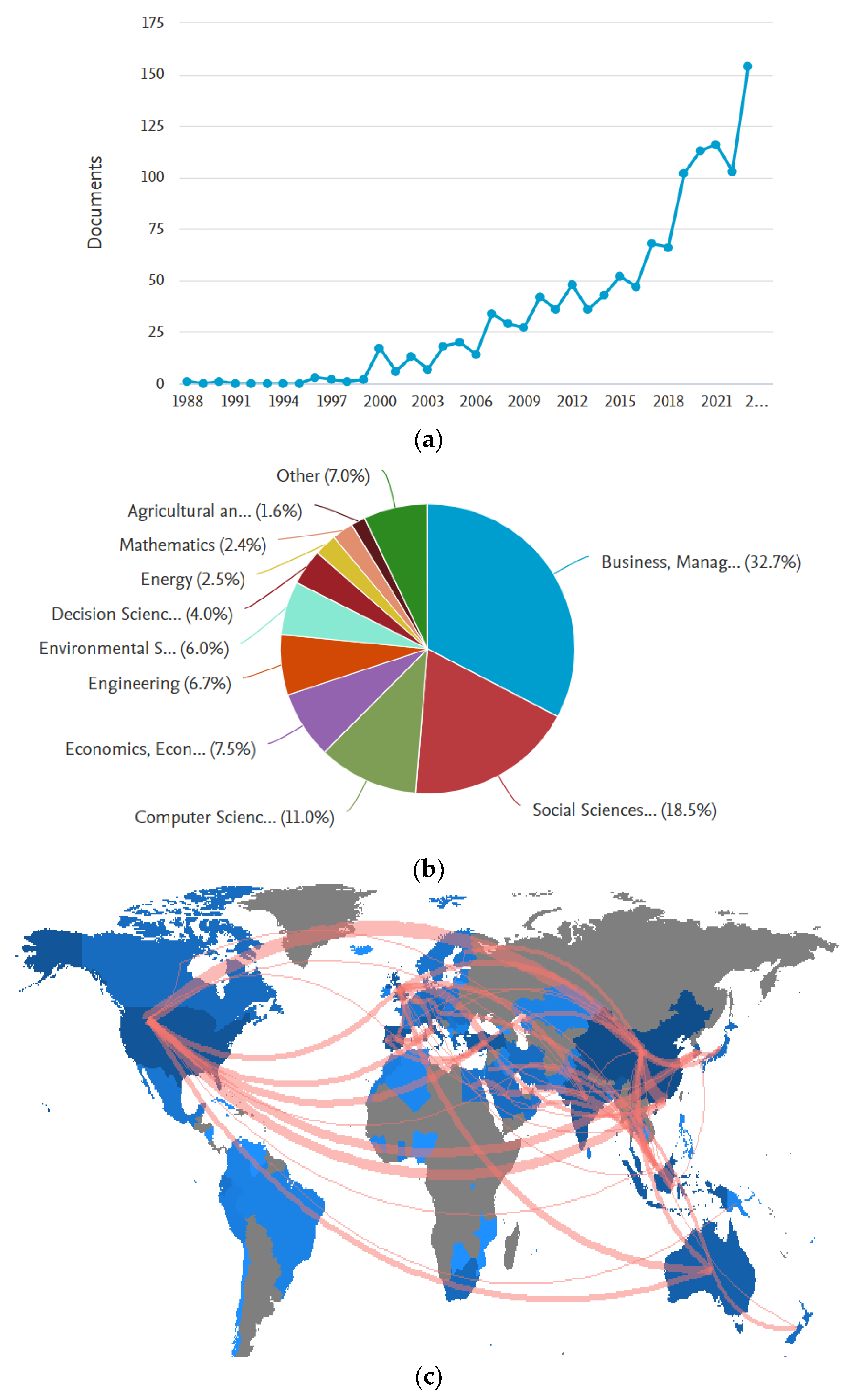

2.5.1. Positioning in the Literature

2.5.2. Distinction from Related Constructs

2.5.3. Theoretical Implications for SERVPERF

2.5.4. Practical Relevance

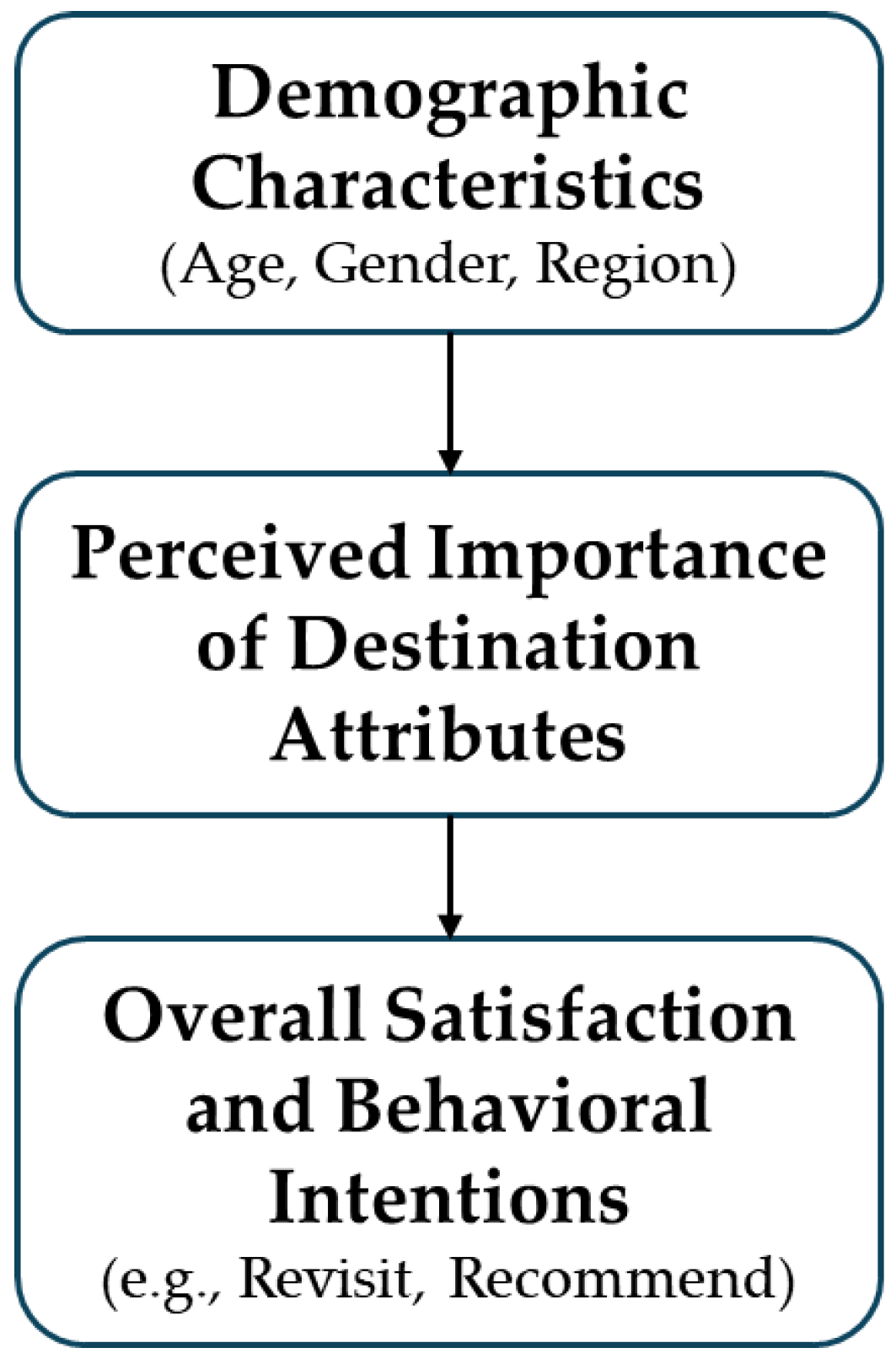

2.6. Conceptual Model and Research Questions

- RQ1. Do tourists’ overall satisfaction scores differ across age, gender, and region of origin?

- RQ2. Does the importance and factorial structure of destination attributes vary by those demographics?

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Population and Sample Design

- Sampling frame: All international passengers departing Mariscal Sucre Airport on commercial flights during the 2022 high-season windows, which the Ministry of Tourism identifies as yielding the broadest mix of source regions and travel purposes.

- Selection method: Systematic interval sampling within each outbound flight, with quotas proportional to aircraft capacity, thereby avoiding carrier or time-band bias. In addition, regional strata (Latin America, North America, Europe, Asia–Pacific, Australia) were aligned with 2022 arrival shares published by National Institute of Statistics and Censuses of Ecuador—INEC (2023), in line with UNE-ISO 20252:2019 (International Organization for Standardization—ISO, 2019).

- Sample-size rationale: Using Cochran’s finite-population correction (Equation (1)) with N = 1,264,913 inbound tourists (National Institute of Statistics and Censuses of Ecuador—INEC, 2023), a 95% confidence level (z = 1.96), p = q = 0.50, and e = 0.05 yielded a minimum of 385 cases. The final 407 usable questionnaires reduce the margin of error to 4.9% and exceed power thresholds for the subsequent MANOVA and multi-group CFA (Cochran, 1977; Daniel, 1999).

- N: Population size.

- p: Probability of success (0.5).

- q: Probability of failure (0.5).

- e: Researcher error (5%).

- z: Constant of the normal distribution is 1.96 for the 95.5% confidence level.

3.2. Survey Instrument

- Demographics: Age group (under 25, 25–44, 45 and above), gender, and region of origin (Europe, North America, Latin America, others). Segmenting the sample by age, gender, and region of origin follows recommendations from prior research highlighting how demographic moderators shape tourists’ perceptions and satisfaction (León et al., 2025; F. Zhou et al., 2024).

- Attribute Evaluation: Tourists rated 26 destination attributes, grouped into three categories: Access attributes (e.g., airport services, transportation); Lodging attributes (e.g., cleanliness, service); and Non-hotel services (e.g., gastronomy, safety).

- Each attribute was rated using two scales: Importance (1 = Not important, 5 = Very important) and Satisfaction (1 = Very dissatisfied, 5 = Very satisfied).

- Open questions (optional) allowed participants to provide qualitative impressions or suggestions.

Rationale for Using SERVPERF in Volatile, Information-Scarce Contexts

3.3. Data Processing and Analysis

- Index Construction: A satisfaction index was calculated for each attribute by weighting satisfaction scores by importance to better reflect perceived value. The index helped identify the most influential attributes in overall tourist experience. For each respondent a Customer Satisfaction Index (CSI) was computed with Equation (2), presenting the weighted aggregation used to calculate the CSI, following methods widely adopted in tourism research (Alegre & Garau, 2010; Tsiotsou, 2005).

- 2.

- Segment comparison: Mean CSI scores and individual-attribute ratings were contrasted across the twelve demographic cells (4 age × 2 gender × 3 region) through one-way ANOVA with Games–Howell post hoc tests (α = 0.05). Partial η2 provided effect sizes, while chi-square tests served as measurement invariance checks for categorical splits.

- 3.

- Consensus analysis: Kendall’s W quantified intra-segment agreement on attribute priorities. Values ≥ 0.70 were interpreted as strong consensus (Vidal-Meliá et al., 2025), guiding the managerial relevance of segment profiles.

- 4.

- Exploratory factor analysis (EFA): To uncover latent structures among the 26 attributes, principal-axis factoring with Promax rotation (κ = 4) was run on the full sample (n = 407). Factor retention followed (a) eigenvalues > 1, (b) scree plot inflection, and (c) parallel analysis; sampling adequacy was confirmed by KMO ≥ 0.80 and Bartlett’s test p < 0.001.

- 5.

- Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and multi-group invariance: A four-factor SERVPERF model was estimated with robust maximum-likelihood (MLR). Goodness-of-fit thresholds were CFI ≥ 0.95, TLI ≥ 0.95, RMSEA ≤ 0.06, and SRMR ≤ 0.08 (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Multi-group CFA then evaluated configural, metric, and scalar invariance across age, gender, and region; ΔCFI ≤ 0.01 signaled acceptable invariance (Cheung & Rensvold, 2002).

- 6.

- Multivariate mean testing and validity diagnostics: MANOVA examined simultaneous mean differences in CSI and factor scores; significant omnibus effects were decomposed by Games–Howell contrasts. Common-method variance was checked with Harman’s single-factor test (<30%), multicollinearity with VIF < 3, and parameter stability with 2000-draw bootstrap standard errors.

- 7.

- Validity and reliability diagnostics: Internal consistency and construct validity satisfied all recommended cut-offs: Cronbach’s α ranged from 0.88 to 0.94, Composite Reliability (CR) from 0.88 to 0.95, and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) from 0.53 to 0.77. Discriminant validity was confirmed through heterotrait–monotrait ratios (HTMT < 0.85). Multi-group CFA established configural, metric, and scalar invariance across age, gender, and region, with ΔCFI ≤ 0.01 in every step. Detailed coefficients and fit indices appear in Table 3 (measurement-model diagnostics) and Table 4 (invariance testing). All analyses were run in SPSS 27 and R 4.3 (lavaan, psych).

3.4. Final Considerations

4. Results

4.1. Sample Profile

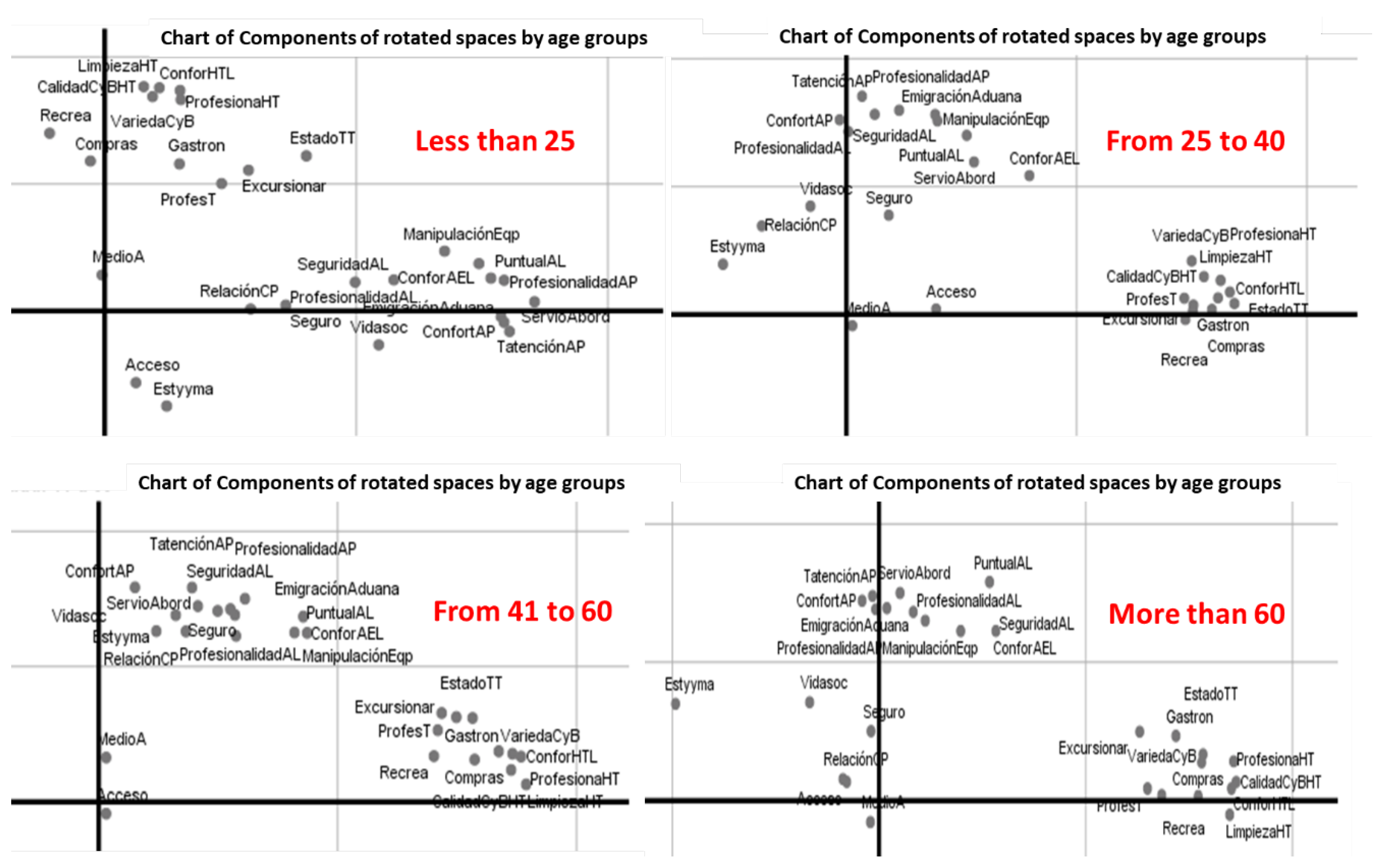

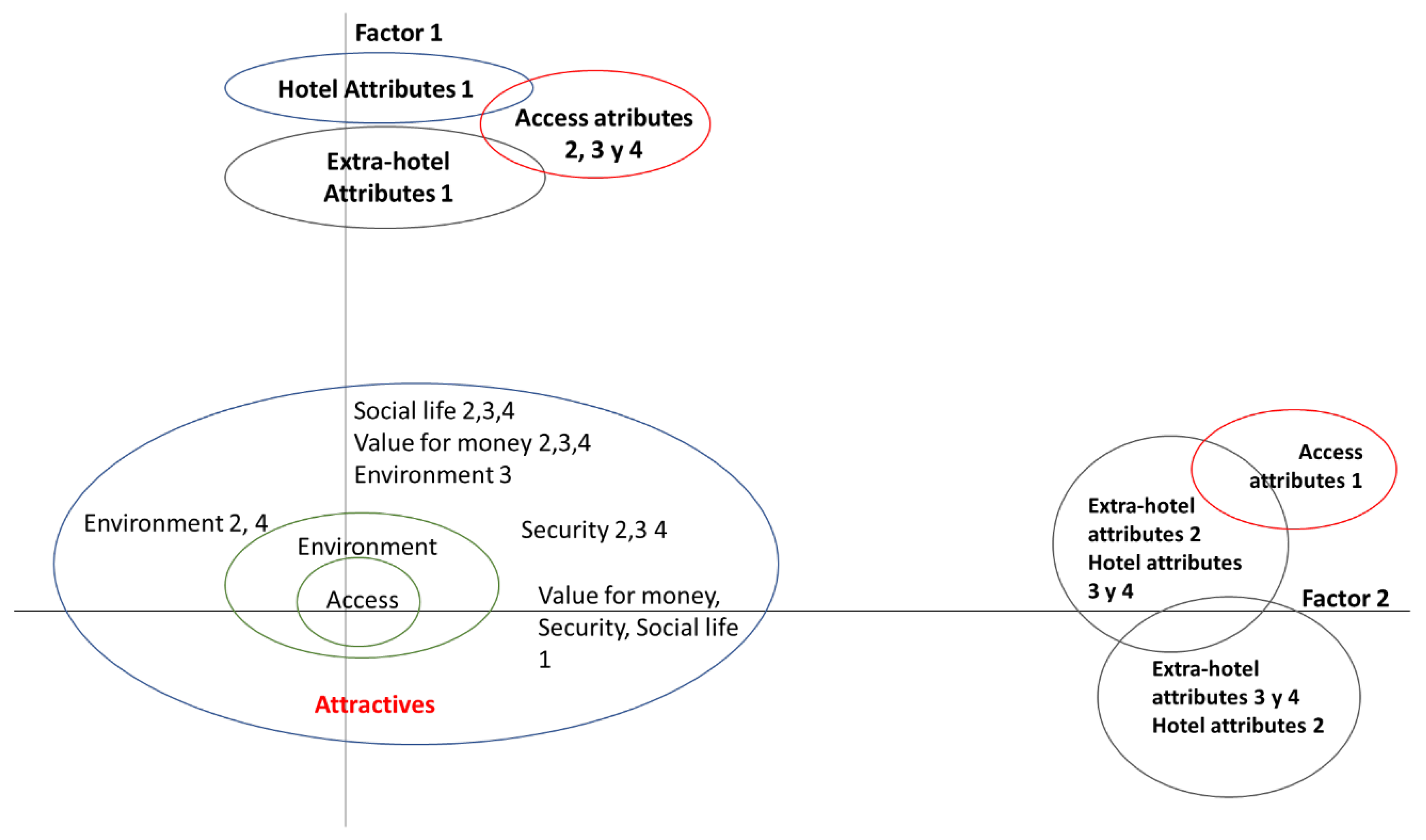

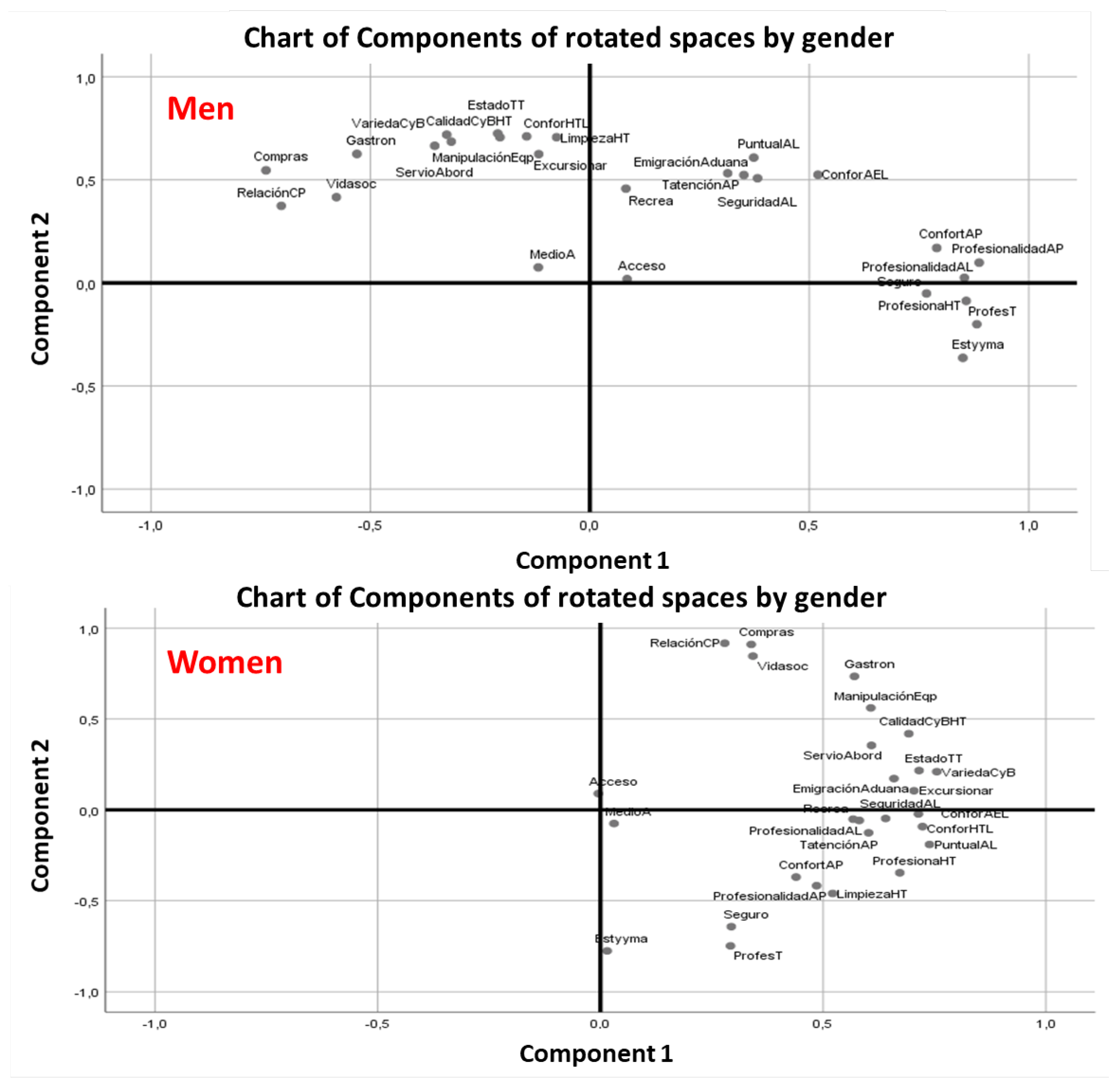

4.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis

- KMO values ranged from 0.886 (Latin American visitors) to 0.773 (tourists under 25), all above the acceptable threshold (≥0.70).

- In every group—except the combined Asia–Australia segment (determinant = 0.0)—the same five-factor solution was retained. Differences in explained variance suggest greater internal heterogeneity in segments with lower KMO values.

4.3. Measurement-Model Diagnostics

- Indicator loadings: Standardized loadings for the 26 items ranged from 0.63 to 0.88 (p < 0.001), well above the 0.50 practical-significance benchmark, yielding item reliabilities (λ2) between 0.40 and 0.77.

- Internal consistency: Composite Reliability (CR) values fell between 0.81 and 0.93, and Cronbach’s α coefficients fell between 0.78 and 0.92, surpassing the ≥0.70 guideline for both exploratory and confirmatory work (Hair et al., 2022).

- Convergent validity: Average Variance Extracted (AVE) exceeded the recommended 0.50 threshold for each dimension—Access = 0.55, Lodging = 0.59, Extra-hotel Services = 0.57, and Attractions = 0.62—indicating that the indicators capture more than half of the variance in their respective factors.

- Discriminant validity: Heterotrait–monotrait ratios (HTMT) ranged from 0.31 to 0.84, all below the conservative 0.85 ceiling. The Fornell–Larcker criterion was also satisfied: for every dimension pair, the squared inter-dimension correlation was lower than the smaller of the two AVE values, confirming that each factor shares more variance with its own items than with any other latent dimension.

4.4. Descriptive Satisfaction Indices

4.5. Hypothesis Testing

4.6. Post Hoc Segment Profiles

5. Discussion

6. Implications

6.1. Implications for Theory

6.1.1. Conditional Validity of SERVPERF in the Global South

6.1.2. Demographic Capital Inside Performance-Based Models

6.1.3. Satisfaction as a Context-Mediated Construct

6.1.4. Directions for Future Research

6.2. Implications for Practice

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adie, B. A., Taheri, B., & Gannon, M. (2023). Natural heritage tourism: Does co-creation matter? Journal of Ecotourism, 22(1), 144–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, R. (2014). Habitus, capital and patterns of taste in tourism consumption: A study of Western consumers in India. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 38(4), 487–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegre, J., & Garau, J. (2010). Tourist satisfaction and dissatisfaction. Annals of Tourism Research, 37(1), 52–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaro-Navarro, J. L., & Andrés-Martínez, M.-E. (2024). Changes in guests’ hotel evaluations due to COVID-19: The case of the world heritage city of Cuenca. Tourism and Hospitality Management, 30(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoah, F., & Amoah, L. N. A. (2019). Tourist experience, satisfaction, and behavioural intentions of rural tourism destinations in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 8(4), 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Barusman, A. R. P., & Rulian, E. P. (2020). Customer satisfaction and retention and its impact on tourism in hotel industry. Utopia y Praxis Latinoamericana, 25, 117–126. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, G. S. (1993). Human capital (3rd ed.). University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bichler, B. F., & Pikkemaat, B. (2021). Winter sports tourism to urban destinations: Identifying potential and comparing motivational differences across skier groups. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, 36, 100420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohórquez, E., Pérez, M., Peña, H., & Padilla, A. (2020). Strategic direction and customer satisfaction: Case of the tourist transport company liberpesa S.A. In Á. Rocha, A. Abreu, J. de Carvalho, D. Liberato, E. González, & P. Liberato (Eds.), Advances in tourism, technology and smart systems. smart innovation, systems and technologies (Vol. 171, pp. 437–446). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, A. P., Rodrigues, P., & Matias, Á. (2016). Customer satisfaction and expenditure behaviour in musical festivals: The optimus primavera sound case study. Tourism Economics, 22(4), 825–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. (1984). Distinction: A social critique of the judgment of taste. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. (1986). The forms of capital. In J. G. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education (pp. 241–258). Greenwood Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bravo Macías, M. A., Cruzatty Quijije, J. S., & Hermoza Robles, C. I. (2024). Impacto de la inseguridad en el sector turístico de Ecuador. Ciencia Latina Revista Científica Multidisciplinar, 8(4), 8638–8662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campo, S., & Garau, J. B. (2008). The influence of nationality on the generation of tourist satisfaction. Tourism Analysis, 13(1), 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cankül, D., Kaya, S., & Kızıltaş, M. Ç. (2024). The effect of gastronomic experience on restaurant image, customer perceived value, customer satisfaction and customer loyalty. International Journal of Gastronomy and Food Science, 36, 100908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillat, F. A., Jaramillo, F., & Mulki, J. P. (2007). The validity of the SERVQUAL and SERVPERF scales: A meta-analytic view of 17 years of research across five continents. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 18(5), 472–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvache-Franco, O., Carvache-Franco, W., & Cevallos-Sierra, C. (2023). Segmentation by motivation and tourist satisfaction in emerging urban destinations: Evidence from Latin America. PLoS ONE, 18(2), e0281234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassandra, C., Gunawan, A., Teguh, W., Adi, S., & Gui, A. (2021). The influence of information quality, system quality, service quality on customer satisfaction for hotel online reservation. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Information Technology, 99(24), 6091–6101. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo Canalejo, A. M., & Jimber del Río, J. A. (2018). Quality, satisfaction and loyalty indices. Journal of Place Management and Development, 11(4), 428–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chango-Cañaveral, P. M., Jaya-Jaramillo, D. E., Quezada-Sarmiento, P. A., & Salas-Álvarez, W. T. (2022, June 22–25). Analysis of the quality service of the hotel villa colonial through the servqual method and cloud computing tools. 17th Iberian Conference on Information Systems and Technologies (CISTI) (pp. 1–7), Madrid, Spain. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-S. (2017). A novel method for minimizing the average waiting time of visitors during an airport pickup service. Journal of Industrial and Production Engineering, 34(4), 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R. J. C., Kung, S.-F., & Phou, S. (2020). Expectation formation under uncertainty: Evidence from emerging tourism markets. Journal of Travel Research, 59(7), 1291–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 9(2), 233–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiny, M., Bencharef, O., & Chihab, Y. (2021, May 19–20). Towards a machine learning and datamining approach to identify customer satisfaction factors on Airbnb. 2021 International Conference on Optimization and Applications, ICOA 2021, Wolfenbuttel, Germany. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H., & Choi, H. Y. (2019). Influence of physical environment and medical service quality on customer satisfaction in medical travel to Korea. Asia Life Sciences, 1, 465–476. [Google Scholar]

- Ciavolino, E., Lagetto, G., Montinari, A., Al-Nasser, A. D., Al-Omari, A. I., Zaterini, M. J., & Salvatore, S. (2020). Customer satisfaction and service domains: A further development of PROSERV. Quality and Quantity, 54(5–6), 1429–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran, W. G. (1977). Sampling techniques (3rd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, G., Pereira, E., Martins, R., & Mascarenhas, M. (2023). The importance of perceived quality for golf course member satisfaction and loyalty in tourism deprivation times. Journal of Global Sport Management. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, J. J., & Taylor, S. A. (1992). Measuring service quality: A reexamination and extension. Journal of Marketing, 56(3), 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, W. W. (1999). Biostatistics: A foundation for analysis in the health sciences (7th ed.). John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Demydyuk, G. V., & Carlbäck, M. (2024). Balancing short-term gains and long-term success in lodging: The role of customer satisfaction and price in hotel profitability model. Tourism Economics, 30(4), 844–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dmitrović, T., Knežević Cvelbar, L., Kolar, T., Makovec Brenčič, M., Ograjenšek, I., & Žabkar, V. (2009). Conceptualizing tourist satisfaction at the destination level. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 3(2), 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolnicar, S. (2008). Market segmentation in tourism. In A. Woodside, & D. Martin (Eds.), Tourism management: Analysis, behaviour and strategy (pp. 129–150). CABI. [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer, L., & Kim, C. (2003). Destination competitiveness: Determinants and indicators. Current Issues in Tourism, 6(5), 369–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ersen, M., Keskin, A., & Atalan, A. (2023). A study on the analysis of customer satisfaction in hotel businesses in Istanbul with the kano model. In G. Catenazzo (Ed.), Cases on traveler preferences, attitudes, and behaviors: Impact in the hospitality industry (pp. 256–270). IGI Global. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frías-Jamilena, D. M., Sabiote-Ortiz, C. M., Martín-Santana, J. D., & Beerli-Palacio, A. (2018). The effect of Cultural Intelligence on consumer-based destination brand equity. Annals of Tourism Research, 72, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furrer, O., Liu, B. S. C., & Sudharshan, D. (2000). The relationships between culture and service quality perceptions: Basis for cross-cultural market segmentation and resource allocation. Journal of Service Research, 2(4), 355–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Reinoso, N. (2021). Segmentación por motivaciones y valoración del turismo interior en el destino Manta, Manabí, Ecuador. Innovar, 31(80), 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Sedeño, M. A., & García Tejera, M. C. (2013). Estimation of content validity in a scale for assessing the degree of gender violence endured by adolescents. Acción Psicológica, 10(2), 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, B., & Kim, D. (2022). Analyzing user-generated content to improve customer satisfaction at local wine tourism destinations: An analysis of Yelp and TripAdvisor reviews. Consumer Behavior in Tourism and Hospitality, 17(4), 413–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, B. P., Salgaonkar, P., & Hegde, P. G. (2007). SERICSAT: The development of a preliminary instrument to measure service recovery satisfaction in tourism. International Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Administration, 8(1), 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghonim, M. A., Zakaria Elsawy, W., Elsotouhy, M. M., & Khashan, M. A. (2024). The Impact of marketing 4.0 on customer satisfaction and engagement: The distinctive role of brand interaction in the egyptian hotel industry. International Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Administration, 25(3), 475–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Rodríguez, J. C., & Acevedo-Navas, C. (2021). Risk diagnosis of the Latin American tourism sector from 2020 to 2022. Revista Científica General José María Córdova, 19(34), 333–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Rodríguez, M. R., Díaz-Fernández, M. C., & Pacheco Gómez, C. (2020). Facial-expression recognition: An emergent approach to the measurement of tourist satisfaction through emotions. Telematics and Informatics, 51, 101404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grechyn, V., & McShane, I. (2021). “Seriously, Australia, why are you so stingy with Wi-Fi?”: Customer satisfaction with Wi-Fi speed in Australian hotels and lessons for public Wi-Fi provision. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology, 12(4), 730–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grönroos, C. (1997). From marketing mix to relationship marketing: Towards a paradigm shift in marketing. Management Decision, 35(4), 322–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, R. (2002). The australian country market: A European case study on marketing regional products and services in a cyber mall. Journal of Business Research, 55(8), 637–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2022). A primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Haywood, K. M., & Muller, T. E. (1988). The urban tourist experience: Evaluating satisfaction. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 12(2), 453–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, L.-H., Chung, C.-W., Lin, S.-P., & Lin, L.-F. C. (2010). Visitors’ involvement, perceived value, satisfaction and behavioural intention on tourist express trains in Taiwan. International Journal of Services, Technology and Management, 13(3–4), 305–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-C. (2023). Low-cost airlines not so low-cost—Exploring the relationships among travel motivation, service quality and satisfaction: The moderating roles of perceived value. Research in Transportation Business and Management, 49, 101008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Finance Corporation—World Bank. (2022). Creating markets in Ecuador: A country private sector diagnostic. World Bank Group. Available online: https://www.ifc.org/en/insights-reports/2021/cpsd-ecuador (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- International Organization for Standardization—ISO. (2019). Market, opinion and social research, including insights and data analytics—Vocabulary and service requirements (UNE-ISO 20252:2019). ISO.

- Jin, N. P., Lee, S., & Lee, H. (2015). The effect of experience quality on perceived value, satisfaction, image and behavioral intention of water park patrons: New versus repeat visitors. International Journal of Tourism Research, 17(1), 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamyabi, M., Alipour, H., & Rezapouraghdam, H. (2023). Assessing the mediating role of destination image on the perceived value and satisfaction of people with disabilities. In M. Rodrigues, & M. Carvalho (Eds.), Exploring niche tourism business models, marketing, and consumer experience (pp. 32–53). IGI Global. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khassawneh, O., Mohammad, T., Bouchon, F., & Behery, M. (2024). Eco-innovation and customer satisfaction in the hospitality industry in Dubai: The role of green leadership. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality and Tourism, 23(3), 413–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-Y., & Canina, L. (2015). An analysis of smart tourism system satisfaction scores: The role of priced versus average quality. Computers in Human Behavior, 50, 610–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocabulut, Ö., & Albayrak, T. (2019). The effects of mood and personality type on service quality perception and customer satisfaction. International Journal of Culture, Tourism, and Hospitality Research, 13(1), 98–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreusser, O. T. (1928). Automobile bodies, from the abstract customer’s viewpoint (Vol. 23). SAE Technical Papers. SAE International. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusumawardani, A. M., & Aruan, D. T. H. (2019). Comparing the effects of service quality and value-for-money on customer satisfaction, airline image and behavioural intention between full-service and low-cost airlines: Evidence from Indonesia. International Journal of Tourism Policy, 9(1), 27–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, S.-Y., Jusoh, A., & Khalifah, Z. (2016). The influence of service quality on satisfaction: Does gender really matter? Intangible Capital, 12(2), 444–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanke, P., & Varsha Paul, E. (2022). Is there anything new? Exploring the conceptual structure of customer satisfaction research in tourism and hospitality. Tourism, 70(4), 730–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, L.-Y., Hew, T.-S., Lee, V.-H., & Ooi, K.-B. (2015). An SEM-artificial-neural-network analysis of the relationships between SERVPERF, customer satisfaction and loyalty among low-cost and full-service airline. Expert Systems with Applications, 42(19), 6620–6634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León, C. J., González, M., & de León, J. (2025). Satisfaction and sustainability concerns in whale-watching tourism: A user-generated content model. Tourism Management, 98, 104654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberato, D., Liberato, P., & Silva, M. (2020). Shopping tourism: Comparative analysis of the cities of oporto and lisbon as shopping destinations. In V. Katsoni, & T. Spyriadis (Eds.), Cultural and tourism innovation in the digital era (pp. 365–379). Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubis, M., Lubis, A. R., Pratiwi, S. H., & Yuherisna, D. P. (2021, February 18–20). Customer satisfaction assessment coffee roaster restaurant using SERVQUAL: Utilization of customer relationship management (CRM) application. DSDE ‘21: Proceedings of the 2021 4th International Conference on Data Storage and Data Engineering (pp. 85–92), Barcelona, Spain. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marković, S., & Šebrek, J. K. (2020). Service quality measurement in rural tourism: Application of RURALQUAL model. Academica Turistica, 13(2), 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, J. C., & Bustamante, J. (2019). Service quality perceptions among domestic and foreign tourists: Evidence from Ecuador’s coastal destinations. International Journal of Housing Markets and Analysis, 12(3), 387–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín Hernández, J., Pérez-Gálvez, J. C., & Díaz Molina, M. (2019). Tourist loyalty and satisfaction in coastal destinations: The role of demographic factors. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 38, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mestanza-Ramón, C., Chica-Ruiz, J. A., Anfuso, G., Mooser, A., & Botero, C. M. (2020). Tourism in continental ecuador and the galapagos Islands: An Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) perspective. Water, 12(6), 1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhlongo, Z., Ntshangase, S. D., & Ezeuduji, I. O. (2025). Youths’ entrepreneurial intention for tourism and nontourism businesses: The influence of entrepreneurship education and gender. Journal of the International Council for Small Business, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, H., Yoon, H. J., & Han, H. (2016). Role of airport physical environments in the satisfaction generation process: Mediating the impact of traveller emotion. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 21(2), 193–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabi, M. N. U., Khan, S. M., Misbauddin, S. M., & Fatema, K. (2023). Why is India a popular destination for Bangladeshi medical tourists? A study based on perceived justice by Bangladeshi patients. International Journal of Pharmaceutical and Healthcare Marketing, 17(3), 265–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, G., & Carr, N. (2018). Comfort and the tourism accommodation sector: A central, yet under-studied issue. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 74, 224–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Statistics and Censuses of Ecuador—INEC. (2023). Boletín técnico de estadísticas de turismo receptivo 2022–2023. Available online: https://www.ecuadorencifras.gob.ec (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Ogunjinml, A. A., & Binuyo, L. Y. (2018). Relationship between destination service quality and tourists’ satisfaction in ikogosi warm spring resort, Nigeria. Tourism, 66(4), 362–378. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, H., & Kim, K. (2017). Customer satisfaction, service quality, and customer value: Years 2000–2015. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 29(1), 2–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R. L. (2010). Satisfaction: A behavioral perspective on the consumer (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Otnes, C., & McGrath, M. A. (2019). Consumer acculturation and cross-cultural marketing. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Özkul, E., Bilgili, B., & Koç, E. (2020). The Influence of the color of light on the customers’ perception of service quality and satisfaction in the restaurant. Color Research and Application, 45(6), 1217–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, A., Hassan, S., Shetty, D. K., Shenoy, S. S., Shreepathy Ranga Bhatta, B., Panwar, N., & Shetty, A. (2024). An exploratory analysis of gastronomy tourism: The impact of dining attributes on satisfaction among young adult Indian travelers. Environment and Social Psychology, 9(4), 2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantiyasa, I. W., Sutiarso, M. A., & Suprapto, I. N. A. (2023). Evaluation of Agriculture-based tourism products in tinggan traditional village. Jurnal Ilmiah Ilmu Terapan Universitas Jambi, 7(1), 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V. A., & Berry, L. L. (1994). Reassessment of expectations as a comparison standard in measuring service quality: Implications for further research. Journal of Marketing, 58(1), 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasaco-González, B. S., Campón-Cerro, A. M., Moreno-Lobato, A., & Sánchez-Vargas, E. (2023). The role of demographics and previous experience in tourists’ experiential perceptions. Sustainability, 15(4), 3768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, P. L. (2005). Tourist behaviour: Themes and conceptual schemes. Channel View. [Google Scholar]

- Petcu, M. A., Sobolevschi-David, M. I., & Curea, S. C. (2021). Configuration of an integrated quality-social responsibility-performance management system in the hospitality industry. Case studies: Balneary tourism romania. Sustainability, 13(13), 7303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Campdesuñer, R., García-Vidal, G., Sánchez-Rodríguez, A., & Martínez-Vivar, R. (2017). Structural equation model: Influence on tourist satisfaction with destination atributes. Tourism and Hospitality Management, 23(2), 219–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Campdesuñer, R., Sánchez-Rodríguez, A., García-Vidal, G., & Martínez-Vivar, R. (2018). Neural networks to analyse the incidence of customer satisfaction in their loyalty in a tourist destination. International Journal of Services, Economics and Management, 9(2), 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, B. J., & Gilmore, J. H. (1999). The experience economy: Work is theatre & every business a stage. Harvard Business Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie, J. R. B., & Crouch, G. I. (2005). The competitive destination: A sustainable tourism perspective. CABI Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Casado, N., Navarro-Azorín, J. M., Jiménez-Medina, M. P., & Cubillas-Para, C. (2023). Use of customers’ satisfaction survey to segment the tourism market. In Teaching cases in tourism, hospitality and events (pp. 231–239). CAB International. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Rebull, M.-V., Rudchenko, V., & Martín, J.-C. (2018). The antecedents and consequences of customer satisfaction in tourism: A systematic literature review. Tourism and Hospitality Management, 24(1), 151–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiq, A., Mostafiz, M. I., & Taniguchi, M. (2019). Using SERVQUAL to determine Generation Y’s satisfaction towards hoteling industry in Malaysia. Journal of Tourism Futures, 5(1), 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P., Chen, I. S. N., & Luk, S. T. K. (2012). Gender and age as moderators in the service evaluation process. Journal of Services Marketing, 26(2), 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shyju, P. J., Singh, K., Kokkranikal, J., Bharadwaj, R., Rai, S., & Antony, J. (2021). Service quality and customer satisfaction in hospitality, leisure, sportand tourism: An assessment of research in Web of Science. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism, 24(1), 24–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryani, D., Rustiawan, A., & Jannah, A. A. (2023). Factors associated with Food Safety Practices (FSP) among visitors in the Depok Beach Area in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Public Health of Indonesia, 9(3), 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toni, M., Jithina, K. K., & Thomas, K. V. (2023). Antecedents of patient satisfaction in the medical tourism sector: A review. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, 7(4), 2273–2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travar, M., Milojica, V., & Stankov, U. (2022a). Are image and quality of tourist services strategic determinants of satisfaction? Millennials’ perspective in emerging destinations. Sustainability, 14(13), 7989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travar, M., Zekanović-Korona, L., & Perić, M. (2022b). Exploring millennial travellers’ satisfaction with destination attributes in an emerging European city. Administrative Sciences, 12(4), 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiotsou, R. (2005). Perceived quality levels and their relation to involvement, satisfaction, and purchase intentions. Marketing Bulletin, 16. Available online: http://marketing-bulletin.massey.ac.nz/V16/MB_V16_N4_Tsiotsou.pdf (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- van Zyl, C. C., & van der Merwe, P. (2022). Critical success factors for developing and managing agri-tourism: A South African approach. In C. Silva, M. Oliveira, & S. Silva (Eds.), Proceeding of the international conference of tourism research (Vol. 15, pp. 536–545). Academic Conferences and Publishing International Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Velastegui-Hernández, J., Bravo, M., & Rodríguez, M. (2024). Assessing service quality in adventure tourism: An application of SERVQUAL in Ecuadorian destinations. Sustainability, 16(1), 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velastegui-Hernández, R., Melo-Fiallos, D., Mayorga-Ases, M., Hernández-Del-Salto, S., Manobanda-Tenelema, E., & Garcia, M. V. (2024). Perceived quality of service in tourist transportation in the city of Baños de Agua Santa, Ecuador. Sustainability, 16(17), 7245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veloso, C. M., Walter, C. E., Sousa, B., Au-Yong-Oliveira, M., Santos, V., & Valeri, M. (2021). Academic tourism and transport services: Student perceptions from a social responsibility perspective. Sustainability, 13(16), 8794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vena-Oya, J., Castaneda-García, J. A., Rodríguez-Molina, M. A., & Frías-Jamilena, D. M. (2021). How do monetary and time spend explain cultural tourist satisfaction? Tourism Management Perspectives, 37, 100788. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10953/3512 (accessed on 25 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Vidal-Meliá, L., Moliner, M. Á., Monferrer, D., Estrada, M., & Quille, K. (2025). Segmenting tourists based on perceived sustainability and satisfaction using machine learning. Journal of Marketing Analytics. Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, A., & Musa, G. (2020). Mobility capital and ageing tourists: Insights from long-stay winter visitors in Malaysia. Tourism Management, 81, 104130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y., Zhu, Y., & Mattingly, H. (2021). Construction and Demonstration of the measurement model of tourist satisfaction in huadu airport. In S. Patnaik (Ed.), Proceeding—Smart city challenges outcomes urban transformation, SCOUT (pp. 62–66). Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulou, P., & Plimakis, S. (2023). The adoption of corporate social responsibility (CSR) policy in the tourism sector: How CSR affects consumer loyalty in the Greek hotel industry. In A. Masouras, C. Papademetriou, D. Belias, & S. Anastasiadou (Eds.), Sustainable growth strategies for entrepreneurial venture tourism and regional development (pp. 1–19). IGI Global Scientific Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, E. C. L., Yang, M. J., & Khoo-Lattimore, C. (2019). The meanings of solo travel for Asian women. Tourism Review, 74(5), 1047–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T., Wu, J., & Zhang, J. (2024). Knowing how satisfied/dissatisfied is far from enough: A comprehensive customer satisfaction analysis framework based on hybrid text mining techniques. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 36(3), 873–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusof, Y., Awang, Z., Jusoff, K., & Ibrahim, Y. (2017). The influence of green practices by non-green hotels on customer satisfaction and loyalty in hotel and tourism industry. International Journal of Green Economics, 11(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F., Huang, S., & Matthews, M. (2024). Understanding solo female travellers in Canada: A two-factor analysis of hotel satisfaction and dissatisfaction using tripadvisor reviews. Tourism and Hospitality, 5(1), 167–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K., & Yao, Z. (2023). Analysis of customer satisfaction in tourism services based on the kano model. Systems, 11(7), 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Variable Levels | Amount | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Man | 187 | 46 |

| Women | 220 | 54 | |

| Age | Under 25 | 88 | 21.6 |

| 25 to 40 | 99 | 24.3 | |

| 41 to 60 | 103 | 25.3 | |

| More than 60 | 117 | 28.8 | |

| Region | Australia | 11 | 2.70 |

| Asia | 21 | 5.16 | |

| Europe | 78 | 19.16 | |

| Latin America | 165 | 40.54 | |

| North America | 132 | 32.43 |

| Axis I | Axis II | Axis III | Axis IV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eigenvalues | 14.5% | 8.75% | 2.92% | 2.53% |

| Contribution to total variance | 25.80% | 22.02% | 21.93% | 13.17% |

| Cumulative percentage of explained variance | 25.80% | 47.82% | 69.73% | 82.91% |

| Dimensions | Lodging | Extra-hotel activity | Access | Attractions |

| Front desk service | 0.912 | 0.231 | 0.056 | −0.013 |

| Animation | 0.899 | 0.255 | 0.058 | 0.003 |

| Variety of food and drinks | 0.893 | 0.266 | 0.073 | −0.037 |

| Accommodation comfort | 0.892 | 0.238 | 0.086 | 0.085 |

| General cleaning | 0.890 | 0.278 | 0.076 | 0.039 |

| Quality of food and drinks | 0.882 | 0.289 | 0.077 | 0.023 |

| Hotel staff professionalism | 0.876 | 0.246 | 0.072 | 0.015 |

| Transport staff professionalism | 0.206 | 0.802 | 0.152 | −0.001 |

| Technical status of transport | 0.272 | 0.799 | 0.166 | −0.041 |

| Excursions | 0.234 | 0.756 | 0.150 | −0.062 |

| General information | 0.188 | 0.743 | 0.093 | −0.078 |

| Gastronomy | 0.151 | 0.737 | 0.098 | −0.104 |

| Recreation | 0.285 | 0.728 | 0.060 | −0.094 |

| Shopping | 0.260 | 0.709 | 0.038 | −0.042 |

| Transport comfort | 0.268 | 0.667 | 0.175 | −0.164 |

| Airline staff professionalism | 0.042 | −0.027 | 0.810 | 0.154 |

| Air safety | 0.054 | 0.074 | 0.767 | 0.171 |

| Customs and immigration | −0.007 | −0.004 | 0.735 | 0.258 |

| Airport staff professionalism | 0.114 | 0.211 | 0.712 | 0.230 |

| Attention time | 0.056 | 0.131 | 0.708 | 0.242 |

| Airport comfort | 0.119 | 0.195 | 0.676 | 0.171 |

| Baggage handling | 0.070 | 0.200 | 0.676 | 0.144 |

| Service on board | 0.029 | 0.184 | 0.673 | 0.331 |

| Airline punctuality | 0.077 | 0.210 | 0.779 | 0.272 |

| Airline comfort | 0.121 | 0.228 | 0.757 | 0.289 |

| Social life | 0.166 | −0.158 | 0.181 | 0.428 |

| Security | −0.084 | −0.057 | 0.078 | 0.421 |

| Reason for travel | 0.021 | −0.167 | 0.220 | 0.411 |

| Access to facilities | −0.137 | −0.094 | 0.076 | 0.385 |

| Aesthetics and environment | 0.019 | −0.093 | 0.189 | 0.343 |

| Factor | CR | AVE | Cronbach’s α | Highest HTMT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Access Services | 0.90 | 0.56 | 0.89 | 0.78 |

| Lodging Quality | 0.93 | 0.66 | 0.92 | 0.80 |

| Extra-Hotel Services | 0.88 | 0.53 | 0.88 | 0.74 |

| Attractions and Environment | 0.95 | 0.77 | 0.94 | 0.71 |

| Moderator | Model | χ2 (df) | CFI | RMSEA | ΔCFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (4 groups) | Configural | 421.8 (216) | 0.957 | 0.046 | - |

| Metric | 447.2 (236) | 0.955 | 0.045 | 0.002 | |

| Scalar | 468.5 (256) | 0.952 | 0.044 | 0.003 | |

| Gender (2 groups) | Configural | 278.6 (216) | 0.962 | 0.038 | - |

| Metric | 290.7 (228) | 0.961 | 0.037 | 0.001 | |

| Scalar | 306.4 (240) | 0.960 | 0.037 | 0.001 | |

| Region (5 groups) | Configural | 633.9 (540) | 0.949 | 0.042 | - |

| Metric | 664.3 (564) | 0.948 | 0.041 | 0.001 | |

| Scalar | 699.7 (588) | 0.947 | 0.041 | 0.001 |

| Variables | Options | KMO | Bartlett Sphericity Significance | Number of Factors | Explained Variance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General | General | 0.929 | 0.000 | 4 | 76.353 |

| Gender | Male | 0.880 | 0.000 | 5 | 54.161 |

| Female | 0.879 | 0.000 | 5 | 52.473 | |

| Age | Less than 25 | 0.773 | 0.000 | 5 | 71.140 |

| 25 to 40 | 0.812 | 0.000 | 5 | 71.500 | |

| 41 to 60 | 0.880 | 0.000 | 5 | 73.230 | |

| More than 60 | 0.829 | 0.000 | 5 | 71.140 | |

| Region | Australia | - | - | 6 | 59.651 |

| Asia | - | - | 6 | 49.565 | |

| Europe | 0.813 | 0.000 | 5 | 78.013 | |

| Latin America | 0.886 | 0.000 | 5 | 77.283 | |

| North America | 0.828 | 0.000 | 5 | 70.884 |

| Satisfaction | Statisticians | Age | Gender | Region of Origin | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <25 | 25–40 | 41–60 | >60 | M | F | Au | As | Eu | LA | NA | ||

| Access | Min | 4.33 | 4.46 | 4.25 | 4.45 | 4.33 | 4.45 | 4.33 | 4.64 | 4.48 | 4.45 | 4.45 |

| Mean | 5.98 | 6.14 | 6.23 | 6.08 | 6.06 | 6.15 | 5.71 | 6.15 | 6.13 | 6.16 | 6.06 | |

| Max | 7.86 | 7.99 | 8.13 | 8.10 | 7.99 | 8.13 | 7.16 | 7.85 | 7.99 | 8.13 | 8.10 | |

| Extra-hotel Services | Min | 7.73 | 7.69 | 7.65 | 7.65 | 4.99 | 5.00 | 5.21 | 5.00 | 4.99 | 4.00 | 5.00 |

| Mean | 7.73 | 7.69 | 7.65 | 7.65 | 6.49 | 6.43 | 6.57 | 6.65 | 6.54 | 6.42 | 6.41 | |

| Max | 7.73 | 7.69 | 7.65 | 7.65 | 8.00 | 8.00 | 7.00 | 7.90 | 8.00 | 8.00 | 8.00 | |

| Lodging | Min | 4.11 | 4.27 | 4.25 | 4.80 | 4.11 | 4.50 | 4.11 | 4.36 | 4.11 | 4.50 | 4.80 |

| Mean | 6.57 | 6.49 | 6.85 | 6.96 | 6.52 | 6.91 | 6.64 | 6.69 | 6.56 | 6.66 | 6.94 | |

| Max | 8.10 | 8.27 | 8.50 | 8.61 | 8.27 | 8.61 | 7.54 | 7.78 | 8.11 | 8.50 | 8.61 | |

| Attractions | Min | 7.24 | 7.33 | 3.43 | 7.52 | 7.24 | 7.43 | 7.62 | 7.33 | 7.24 | 7.43 | 7.43 |

| Mean | 8.16 | 8.35 | 8.33 | 8.51 | 8.26 | 8.42 | 8.09 | 8.11 | 8.27 | 8.32 | 8.49 | |

| Max | 9.05 | 9.12 | 9.29 | 9.48 | 9.12 | 9.48 | 8.74 | 8.90 | 9.05 | 9.29 | 9.48 | |

| General | Min | 5.00 | 4.99 | 4.00 | 5.00 | 7.65 | 7.69 | 7.73 | 7.73 | 7.69 | 7.65 | 7.65 |

| Mean | 6.56 | 6.43 | 6.45 | 6.41 | 7.65 | 7.71 | 7.73 | 7.73 | 7.72 | 7.67 | 7.65 | |

| Max | 8.00 | 8.00 | 8.00 | 7.98 | 7.65 | 7.73 | 7.73 | 7.73 | 7.73 | 7.69 | 7.65 | |

| Dimensions | Attributes | Gender | Age | Region |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Access | Airline staff professionalism | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Security | 0.765 | 0.261 | 0.551 | |

| Emigration and customs | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Airport staff professionalism | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Attention time | 0.521 | 0.769 | 0.453 | |

| Airport comfort | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Baggage handling | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Onboard services | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Punctuality | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Airline comfort | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Extra-hotel services | Transport staff professionalism | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Technical condition of transport | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Excursions | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Gastronomy | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Recreation | 0.268 | 0.516 | 0.651 | |

| Shopping | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Lodging | Variety of food and drinks | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Hotel comfort | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Cleaning | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Quality of food and drinks | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Hotel staff professionalism | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Attractions | Social life | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Security | 0.453 | 0.742 | 0.818 | |

| Accessibility | 0.818 | 0.657 | 0.784 | |

| Environment aesthetics | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Value for money | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pérez-Campdesuñer, R.; Sánchez-Rodríguez, A.; García-Vidal, G.; Martínez-Vivar, R.; Valdés-Alarcón, M.E.; De Miguel-Guzmán, M. Demographic Capital and the Conditional Validity of SERVPERF: Rethinking Tourist Satisfaction Models in an Emerging Market Destination. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 272. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15070272

Pérez-Campdesuñer R, Sánchez-Rodríguez A, García-Vidal G, Martínez-Vivar R, Valdés-Alarcón ME, De Miguel-Guzmán M. Demographic Capital and the Conditional Validity of SERVPERF: Rethinking Tourist Satisfaction Models in an Emerging Market Destination. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(7):272. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15070272

Chicago/Turabian StylePérez-Campdesuñer, Reyner, Alexander Sánchez-Rodríguez, Gelmar García-Vidal, Rodobaldo Martínez-Vivar, Marcos Eduardo Valdés-Alarcón, and Margarita De Miguel-Guzmán. 2025. "Demographic Capital and the Conditional Validity of SERVPERF: Rethinking Tourist Satisfaction Models in an Emerging Market Destination" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 7: 272. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15070272

APA StylePérez-Campdesuñer, R., Sánchez-Rodríguez, A., García-Vidal, G., Martínez-Vivar, R., Valdés-Alarcón, M. E., & De Miguel-Guzmán, M. (2025). Demographic Capital and the Conditional Validity of SERVPERF: Rethinking Tourist Satisfaction Models in an Emerging Market Destination. Administrative Sciences, 15(7), 272. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15070272