1. Introduction

Environmental challenges worldwide, such as climate change, increasing waste and resources overconsumption, have become a main struggle for governments, organizations and individuals (

C. P. Wang et al., 2023). These different challenges have pushed these organizations to pursue more environmentally friendly practices to preserve resources and protect nature (

Khatter, 2023). Consequently, both businesses and customers are increasingly interested in preserving the environment and fostering sustainability practices, especially within the tourism industry. ‘Sustainability’ has attracted increasing attention, particularly in tourism (

Shehawy & Ali Khan, 2024), as tourism has contributed significantly to pollution, biodiversity loss, resource depletion and climate change (

Salem et al., 2022).

Studies have explored the primary factors that foster green buying and shift consumer attention towards sustainability practices (

Gulzar et al., 2024). Studies in the tourism sector have explored the factors that might affect green buying, such as biospheric value (

Ferreira et al., 2023), cultural differences (

Chan & Chau, 2021), and trust in sustainability claims, including eco-label certifications (

Testa et al., 2015).

Environmental commitment is the psychological perception of individuals towards the conservation of the environment. Environmental commitment has a direct influence on green purchasing, where people commit to going green (

Sun et al., 2022). On the contrary, green motivation can be conceptualized as a high aspiration to engage in pro-environmental work, encompassing intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Green motives affect consumer choice and induce green buying intention (

L. Wang et al., 2020).

Tavitiyaman et al. (

2024) conceptualized that environmental identity referred to how consumers perceive themselves concerning the environment and identify with their emphasis on environmental protection. Environmental identity strongly affects green purchase intentions, which may serve as an essential moderator variable. A study conducted in Mauritius showed that stronger environmental identity increases intention to participate in ecotourism (

Teeroovengadum, 2019). Therefore, environmental identity is one of the main key factors that influence guests’ decisions to buy environmentally friendly products and services.

Eco-conscious behavior is defined as the serious effort that individuals make to mitigate their environmental impacts by taking necessary steps to preserve the environment (

Nassani et al., 2023). Eco-conscious behavior could mediate the relationship between environmental commitment, green motivation, and green purchasing behavior. For instance, when individuals consciously buy green products based on their habit, those actions strongly reflect their values and identity regarding environmental protection.

While previous studies have examined the relationship between the study variables: environmental commitment, green motivation, Environmental identity, and eco-conscious behavior in different industries and contexts, the study extends the knowledge of understanding the core relationship between those variables in the tourism sector, especially hotels, where some constraints might moderate the dynamics of those relationships differently. Regardless of the existing literature on green purchases and motivation. A remarkable shortage of studies that examine how environmental commitment and green motivation affect green purchasing intentions. Furthermore, limited studies have investigated the moderating role of eco-conscious behavior and the mediating role of environmental identity between environmental commitment, green motivation, and green purchasing intentions.

The study assesses the influence of green commitment and environmental motivation on green purchasing behavior. Furthermore, it will examine the mediating roles of environmental identity and the moderating role of eco-conscious behavior. Moreover, it aims to understand the relationship between eco-conscious behavior, green purchasing behavior, environmental identity, green motivation, and environmental commitment. The study focuses on the travel and tourism industry, offering practical implications that would enhance green buying intentions. Data was collected through a questionnaire distributed to 440 participants staying in Sharm el-Sheikh hotels and analyzed using PLS-SEM.

The study presents a theoretical background, reviewing key constructs such as environmental commitment, green motivation, green identity, eco-conscious behavior, and green purchasing intentions. This is followed by the methodology, data collection process, and analytical techniques used to examine the relationships between the variables. The results section justifies the key findings of the statistical analysis. The article concludes with a discussion of the main findings, theoretical and practical implications, limitations, and suggestions for future research.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Environmental Commitment

Recent research has extensively examined environmental commitment, environmental identity, and the intention of buying green products and services (

Tekin & Çoknaz, 2022). Environmental commitment is described as a continuous dedication to environmental conservation and green initiative participation (

Keles et al., 2023). Research has evaluated the correlation between environmental commitment and its role in shaping environmental identity (

Azizan et al., 2023;

Patwary, 2023;

Lou & Li, 2021). Moreover, the workplace environment and employee awareness about the environment create strong environmental commitment and green identity. Environmental commitment generates heightened environmental consciousness and consequently develops environmental identity and promotes green activities (

Jasothini et al., 2023). Furthermore, Research demonstrates that strong environmental dedication directly impacts consumer intentions toward buying environmentally friendly products. People select eco-friendly items and services because they wish to protect the environment. A study demonstrates that external environmental awareness and government regulations together create changes in consumer behavior (

Hojnik et al., 2020). Furthermore,

Sun et al. (

2022) stated that developing environmental commitment leads to better green buying intentions. Businesses that implement environmentally friendly practices modify their customers’ likelihood to select sustainable products (

Zaidi & Azmi, 2024). Similarly, (

Fuchs et al., 2024) showed that consumers’ environmental attitudes are the key factor because they determine their willingness to buy eco-friendly services.

An Empirical study conducted by (

Haldorai et al., 2023) distributed 440 questionnaires throughout Thai hotels using a three-wave approach to determine the core relationship between eco-organisational identity, service innovation, and organizational performance. The research showed a significant link between green identity and innovation, resulting in better hotel performance while promoting environmental commitment. While another study conducted in Taiwan gathered data from 90 technology manufacturing firms using the latent growth curve model to investigate what factors promote environmental leadership and commitment, the research indicates that environmental commitment has a significant influence in the growth of environmental categorization (

β = 0.43) also it is essential for cultivating environmental commitment and implementing environmental leadership (

L. Hu et al., 2023).

However, previous studies have outlined how green buying intentions, environmental commitment, and environmental identity are related. There is still a gap in defining the dynamic correlation between those variables within the tourism industry, which results in the following hypothesis.

H1a. Environmental commitment positively affects Green Purchasing Intentions.

H1b. Environmental commitment positively affects Environmental Identity.

2.2. Green Motivation

According to (

Ilieva & Vasilev, 2024), the main driving force behind adopting environmentally friendly practices stems from green motivation. Motivation could be intrinsic, as people develop intrinsic motivation through environmental initiative support and eco-friendly behavior adoption, because it satisfies their green values and produces positive self-feelings (

Faraz et al., 2021). Conversely, extrinsic motivation exists when people participate in environmentally friendly activities because they want to receive external rewards such as social approval and financial benefits (

W. Li et al., 2020). In this vein, individuals who base their actions on personal values tend to purchase environmentally friendly products instead of those who let external factors guide their decisions. The assessment of consumer choices requires understanding the distinct motivational philosophies because they produce different effects (

X. Hu et al., 2022).

Studies on green motivation and its impact on environmental identity remain insufficient in the current literature. According to (

Saraiva et al., 2020), both environmental sharing and awareness significantly impact the formation of an environmental identity. In addition, research has explored how motivation influences green intentions across various industries through multiple studies (

Ali et al., 2020;

M. Li & Rabeeu, 2024). In this regard, (

Cheng et al., 2024) investigate the factors affecting people’s willingness to buy green food using meta-analysis. The study evaluated 132 factors from 45 papers to establish the main determinants of green food purchase intentions. Additionally, autonomous motivation positively affects consumers’ purchasing of green products (

Ng et al., 2024). Moreover, utilitarian and hedonic motivations positively affect green purchasing intentions (

S. Kumar & Yadav, 2021). A study was conducted in Cyprus by distributing random surveys to 395 tourists staying in five-star hotels using SME to measure their motivations and how they relate to sustainability practices. The findings showed that behavioral intentions and motivation positively affect adopting eco-friendly behavior and, as a result, buying eco-friendly products (

Ibnou-Laaroussi et al., 2020). Another study surveyed 775 local tourists who stayed in green hotels using SPSS and SME to find out how motivation could affect their choices of eco-friendly accommodations. The results revealed that motivations positively affect the intentions to purchase green services (

L. Wang et al., 2021). Furthermore, it has been illustrated that motivations indirectly encourage green purchasing intentions (

He et al., 2021).

Additionally, the planned behavior theory clarifies the connection between environmental commitment and motivations that encourage positive attitudes towards green products. In this study, environmental commitment and green motivation are crucial factors that affect green purchasing; therefore, TPB serves as a guide to justify the inclusion of this study. Given the previously mentioned results, more research on green motivation is needed, especially measuring its effect on environmental identity and green purchasing intentions. Accordingly, the following hypotheses have been developed.

H2a. Green Motivation positively affects Green Purchasing Intentions.

H2b. Green Motivation positively affects Environmental Identity.

2.3. Environmental Identity

Environmental identity is how individuals identify their relationship with nature (

Ferrajão et al., 2024).

Gravelines et al. (

2022) clarified the meaning of environmental identity as to what extent individuals or organizations see themselves as environmentally friendly and how this identity can affect their choices about sustainable consumption. Green identity is the strong desire to protect the environment, which could be reflected in buying green products and services (

Salsabila & Hartono, 2023). According to a study by (

Blanchard & Paquet, 2023), environmental identity substantially influences behaviors and encourages environmentally responsible actions. In this regard, environmental identity contributes to consistent behaviour as individuals tend to choose environmentally friendly behaviors even when not rewarded, as these behaviors become a reflection of who they are (

Silintowe & Sukresna, 2023). For instance, tourists who believe in sustainability as part of their identity tend to buy environmentally friendly products and engage in eco travel as an expression of their values.

Moreover, Tourists decide to buy green items if they firmly commit to sustainable practices as part of who they are (

Román-Augusto et al., 2022). According to (

X. Wang et al., 2021), promoting a strong sense of environmental identity can significantly boost environmental commitment and encourage intentions for sustainable buying. Additionally, environmental identity is not limited to individuals but can form group dynamics, as collective environmental identities can influence sustainability-related group behaviors (

Zhang et al., 2023). A study by (

Raza et al., 2021) showed that companies with a strong dedication to the environment positively influence their employees to adopt green practices, which, in turn, can help them form a long-term environmental identity.

Furthermore, a study by (

Javaid et al., 2024) used 367 survey responses to assess how environmental identity mediates the relation between mindfulness and environmental fulfillment. The research findings showed that environmental identity positively enhances the relationship between the two variables. According to (

May et al., 2021), organizational identity partially mediates the relationship between employee green behavior and corporate social responsibility (CSR), which enhances environmental sustainability. Research shows that consumers tend to purchase eco-friendly services when they possess a strong green identity and motivation. The current research lacks an investigation of environmental identity as a mediator between green purchasing intention, green motivations and environmental commitment. Consequently, the following hypotheses were developed.

H3. Environmental identity positively affects green purchasing intentions.

H4. Environmental identity mediates the relationship between environmental commitment and green purchasing intentions.

H5. Environmental identity mediates the relationship between green motivation and green purchasing intentions.

2.4. Eco-Conscious Behavior

Individuals who practice eco-conscious behavior actively work to defend the environment while making themselves more environmentally friendly (

Ghali-Zinoubi, 2022). Previous studies have investigated the essential elements that shape eco-conscious behavior (

Rashwan, 2019;

Kautish & Sharma, 2020;

Saleem et al., 2021). The primary determinants of eco-conscious behavior include psychological features, environmental awareness, and environmental attitudes (

Sarmin et al., 2024). Additionally,

Tong et al. (

2023) established that eco-consciousness is a mediating link between environmental concern and the willingness to spend money on eco-friendly products.

Additionally, a study by (

Salem et al., 2022), found that consumers’ perceptions and eco-conscious behavior strongly depend on their understanding of environmental values and carbon emissions. Accordingly, promoting environmentally responsible actions requires identifying the key factors influencing eco-conscious behavior. According to (

Sari et al., 2023), raising environmental awareness among small and medium enterprises is crucial to boosting their desire to implement sustainable practices. Similarly, a study by (

Norton et al., 2022) showed that customers make more sustainable choices when they receive straightforward information about recycling procedures on food packaging. (

Nowacki et al., 2021) stated that personal norms are the main factors affecting consumers’ choice of eco-friendly destinations.

Moreover, an investigation by (

Ahmad et al., 2024) analyzed sustainable packaging behavior among students through 174 distributed surveys utilizing a quantitative research methodology to evaluate their willingness to use eco-friendly packaging. The research discoveries showed the positive impact of environmental knowledge in promoting environmentally conscious actions. The study also suggested that using recyclable packages can be a key factor in fostering eco-conscious behavior.

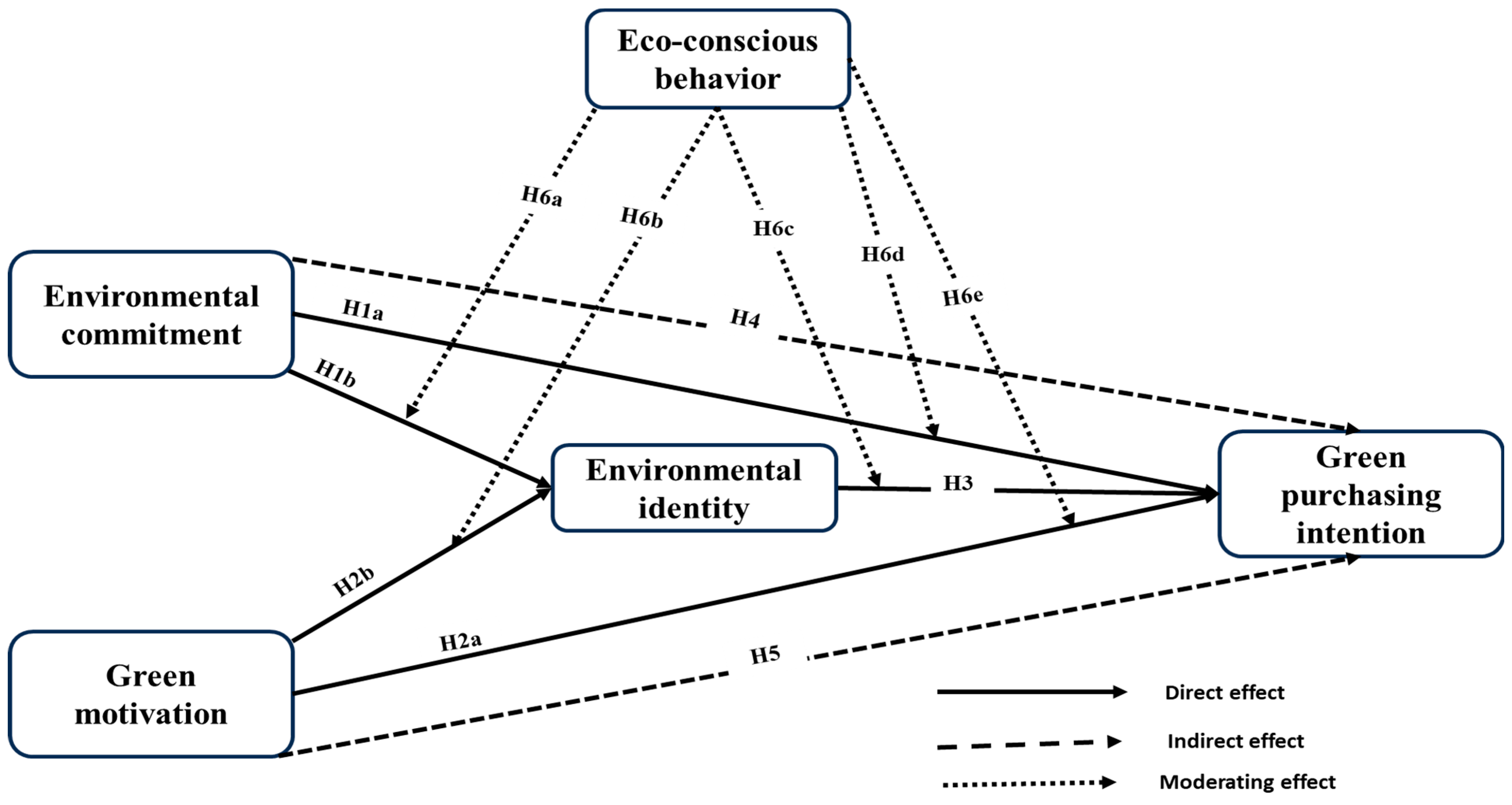

In the realm of tourism, studies have explored eco-friendly behavior. Most studies have concentrated on the primary factors influencing eco-conscious behavior; however, exploring the moderating role of eco-conscious behavior is still limited. Additionally, the moderating influence of eco-conscious behavior between green motivation and green purchasing intentions and its role in environmental identity as a mediator has yet to be thoroughly examined. Based on the previous, five main hypotheses have been formulated (See

Figure 1).

H6a. Eco-conscious behavior moderates the relationship between environmental commitment and environmental identity.

H6b. Eco-conscious behavior moderates the relationship between green motivation and environmental identity.

H6c. Eco-conscious behavior moderates the relationship between environmental identity and green purchasing intention.

H6d. Eco-conscious behavior moderates the relationship between environmental commitment and green purchasing intention.

H6e. Eco-conscious behavior moderates the relationship between green motivation and green purchasing intention.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Instruments and Scales

This study used a quantitative research approach and a structured survey containing two sections. Basic demographic information was collected in the first section, while the second section focused on gathering data related to the study variables. Environmental commitment (EC) comprises eight items that measure the level of Sharm El-Sheikh hotel visitors’ environmental commitment (

Cop et al., 2020). Green motivation (GM) is comprised of nine items, including intrinsic motivation (GIM) and extrinsic motivation (GEM) (

Ali et al., 2020). Environmental identification (EID) consists of twelve items and was developed to estimate visitors’ relationship with the environment (

Clayton et al., 2021). The green purchasing intention (GPI) variable was gauged using five items (

Ali et al., 2020). Similarly, items from (

Chen et al., 2023) were utilized to examine eco-conscious behavior (ECB), (see

Appendix A). Except for the demographic data section, all items were measured using a five-point Likert scale: “1” indicated the lowest rating and “5” the highest. The 5-Likert scale is a widely used and reliable tool for measuring attitudes, perceptions, and opinions in the social science field (

Likert, 1932). It enables participants to express the extent of their agreement or disagreement with specific statements. On the other hand, it must be acknowledged that increasing the number of response options beyond five (such as 7- or 9-point scales) may slightly enhance reliability; however, it can also lead to respondent fatigue, particularly when the questionnaire includes multiple items (

Dawes, 2008). Conversely, having too few options (such as 3-point scales) may lack sufficient discriminatory power and reduce the variance necessary for meaningful statistical analysis (

Matell & Jacoby, 1972). The 5-point Likert is commonly employed in tourism and hospitality studies, primarily due to its simplicity and ease of response, which makes it less burdensome for respondents (

Khairy et al., 2025;

L. Li et al., 2025;

Fouad et al., 2025). To ensure the relevance of the items concerning the study’s objectives, the instrument was reviewed by nine academic experts and thirteen professionals from the green hotel business sector. Based on their feedback, some measurement items were reworded to enhance clarity. In line with

Brislin’s (

1980) recommendations, the original English survey was translated into Arabic by two bilingual experts. A separate team then back-translated the questionnaire into English, resulting in a bilingual version of the survey.

3.2. Data Gathering Process

3.2.1. Scope and Focus of the Study

The survey targeted hotel customers in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt. According to The Green Star Hotel (GSH) program, there are 183 environmentally certified hotels in Egypt, comprising approximately 58,000 rooms in 17 Egyptian cities. More specifically, Sharm el-Sheikh city accounts for 42.6% of green hotels, equivalent to 78 certified green hotels (

El-Tahhan, 2023). These hotels were targeted because it is logical to assume that green-certified hotels strive to comply with certification standards primarily to attract guests who demonstrate high levels of environmental commitment, green motivation, green identity, green purchase intention, and environmentally conscious behaviors. Therefore, they are well-suited for achieving the current study’s objectives, which aim to examine the influence of visitors’ environmental identity and eco-conscious behavior on green purchase intention. Overall, the use of a hotel sample with green certification is theoretically sound and methodologically justified, particularly given the nature of our variables and the study’s environmental orientation. Moreover, the study sought to minimize bias by targeting a sample with diverse demographic characteristics.

3.2.2. Sampling Method and Participants

The study operated a questionnaire developed using Microsoft Forms to collect data. Hotel managers of the targeted hotels were contacted and provided with a questionnaire link or QR code to share with their guests. Hotel managers were also instructed to share the survey link after guests had checked out. Thus, the questionnaire was self-administered by the guests without the presence of hotel staff, and this timing was also intentionally chosen to ensure that guests had sufficient exposure to the hotel’s green environment and services. Additionally, participants were assured that all collected information would be handled with complete confidentiality. The surveys were distributed between May and August 2024; 440 visitors completed the survey. Many studies (e.g.,

Salleh et al., 2016) consider the first column of the sample size table by (

Krejcie & Morgan, 1970), which is based on a 95% confidence level and a 5% margin of error, as a reliable guideline for determining appropriate sample sizes in various research contexts. When the population size is not precisely known, the table recommends using the next highest value. According to (

Krejcie & Morgan, 1970), a minimum sample size of 384 is generally sufficient for large populations (More than 100,000). Therefore, the current study’s sample of 440 participants is considered adequate to ensure generalizability and statistical validity of the findings. The option to turn off skipping questions was activated in the E-questionnaire. Thus, no responses were excluded. The study sample comprised 243 males (55.2%) and 197 females (44.8%). The age groups varied between 25 and 50 years. Regarding educational qualifications, 245 participants (55.7%) held a bachelor’s degree, followed by 81 respondents (18.4%) with a doctorate. Regarding marital status, 305 participants (69.3%) were single, while 131 (29.8%) were married.

Table 1 shows the respondents’ demographic data.

3.3. Statistical Methods

The study’s questionnaire utilized a five-point Likert scale, which may introduce consistent response patterns, potentially resulting in common method bias (CMB) (

Podsakoff et al., 2012). Thus, Harman’s single-factor test (1976) was conducted using SPSS version 22 to examine the single factor that accounted for most of the variance. The total variance clarified by a single factor was 28.25%, below 50%, indicating that CMB was not a significant concern (

Podsakoff et al., 2012). Moreover, all Variance Inflation Factor (VIFs) of items of the study scales were from 1.576 to 2.545, below the accepted cut-off of 5.0 (

Hair et al., 2019). Further, the skewness and kurtosis values were 2.1 and 7.1, respectively (see

Table 2), indicating that issues related to non-normality were avoided (

Curran et al., 1996).

The data was tested using PLS-SEM with SmartPLS 3.0. PLS-SEM is a modern technique widely acknowledged in recent years as a valuable tool in academic research within the context of hospitality and tourism (

L. H. Wang et al., 2022). Unlike traditional covariance-based SEM (CB-SEM), PLS-SEM focuses on maximizing explained variance (

Hair et al., 2011), allowing for a more effective recognition of key factors. Additionally, PLS-SEM is particularly well-suited for exploratory research and theory development, especially when the model involves complex relationships and multiple constructs, as is the case in this study (

Hair et al., 2019). Moreover, PLS-SEM is more appropriate when the primary objective is prediction rather than confirmation (

Sarstedt et al., 2014). Therefore, PLS-SEM is preferred.

4. Results

4.1. Evaluation of Construct Validity and Reliability

The quality of the collected data was assessed using multiple indicators. Internal reliability for each construct was evaluated through Cronbach’s alpha (λ), with values ranging from 0.859 (Green Intrinsic Motivation—GIM) to 0.936 (Environmental Identity—EID) (

Table 2). These values are acceptable, as values above 0.7 showed satisfactory reliability, values above 0.8 reflect good reliability, and values above 0.9 denote excellent reliability (

Nunnally, 1994). Subsequently, convergent validity (CV) was evaluated by analyzing Composite Reliability (CR should be >7), which ranged from 0.898 (Green Intrinsic Motivation—GIM) to 0.944 (Environmental Identity—EID), and Average Variance Extracted (AVE preferred to be >5), which varied between 0.529 (Environmental Commitment—EC) and 0.728 (Green Extrinsic Motivation—GEM) (

Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Accordingly, the CV is acceptable (see

Table 2).

Additionally, discriminant validity (DV) was tested using the Fornell–Larcker matrix and the Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) ratio of correlations. In the Fornell–Larcker matrix, the √AVE for each construct should exceed its correlations with other factors (

Fornell & Larcker, 1981;

Fayyad, 2020). As noted in

Table 3, the √AVE values—displayed in the bold diagonal cells—ranged from 0.727 to 0.850, while the inter-construct correlations listed below them were all below 0.543.

As for the HTMT, values should be <0.90 and preferably below 0.85 (

Gold et al., 2001). This condition was met, as shown in

Table 4, with the maximum HTMT value being 0.577. The DV of the measurement model used in the current study is confirmed based on the results of the Fornell–Larcker matrix and HTMT values.

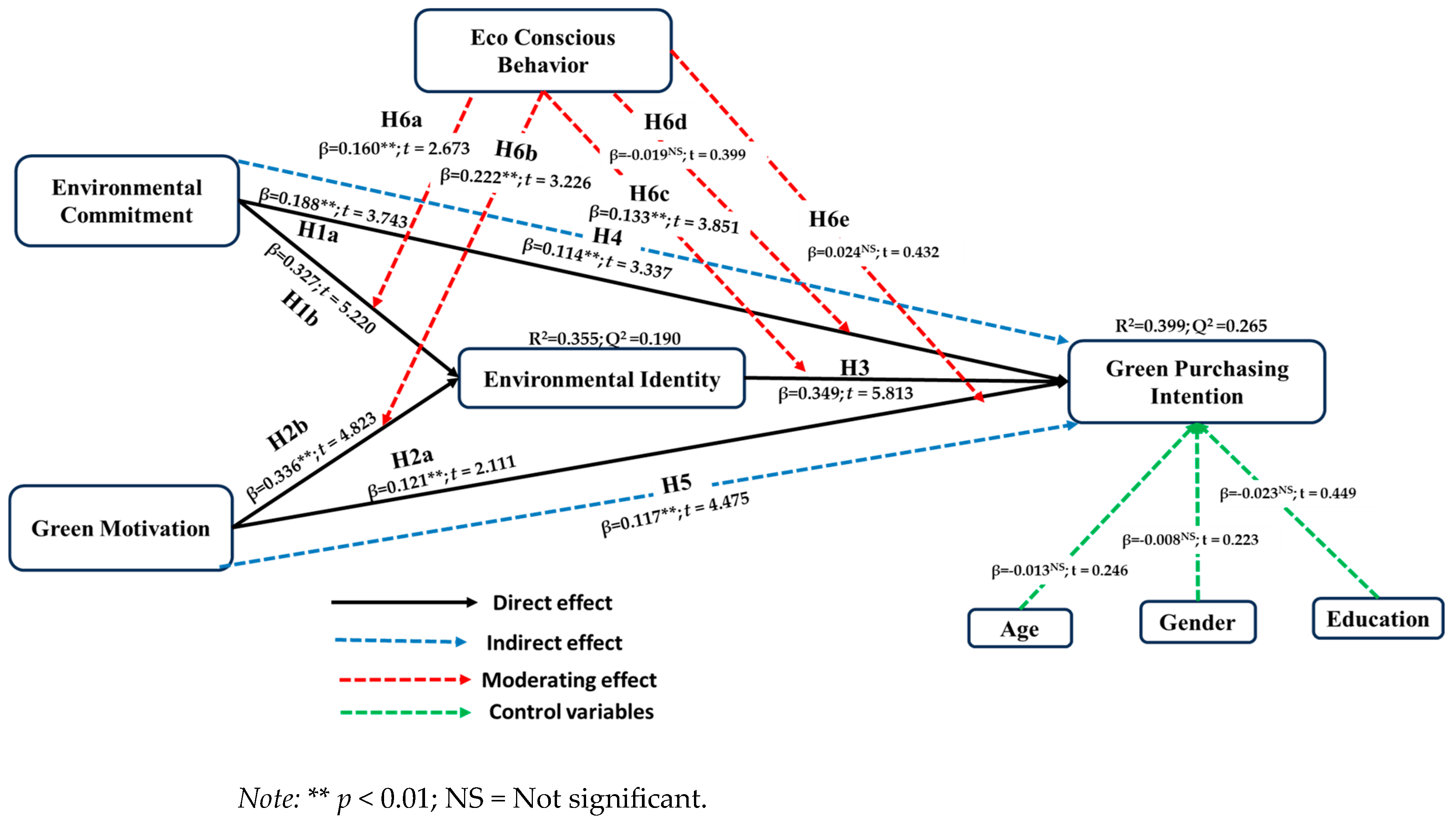

4.2. Hypotheses and Model Testing (Structural Model Assessment)

Table 5 and

Figure 2 demonstrate the findings of the study’s hypothesis testing. The table presents path coefficient values of direct, indirect (mediating), and moderating effects. H1a and H1b were supported because EC affected GPI with β = 0.188 at

p < 0.01 and EID with β = 0.327 and

p < 0.01. Similarly, GM influences GPI at β = 0.121 and

p = 0.035 and EID at β = 0.336 and

p < 0.01, proving H2a and H2b. As for the final direct path, EID influenced GPI (β = 0.349 and

p < 0.01), which supports H3. Regarding the indirect effect, EID mediated the impact of EC on GPI at β = 0.114 with

p < 0.01 and GM on GPI (β = 0.117 with

p < 0.01), proving H4 and H5. Additionally, as shown in

Table 5, none of the control variables—age, gender, and educational level—had a statistically significant effect on GPI, suggesting that these demographic factors did not significantly influence the studied outcomes within the model.

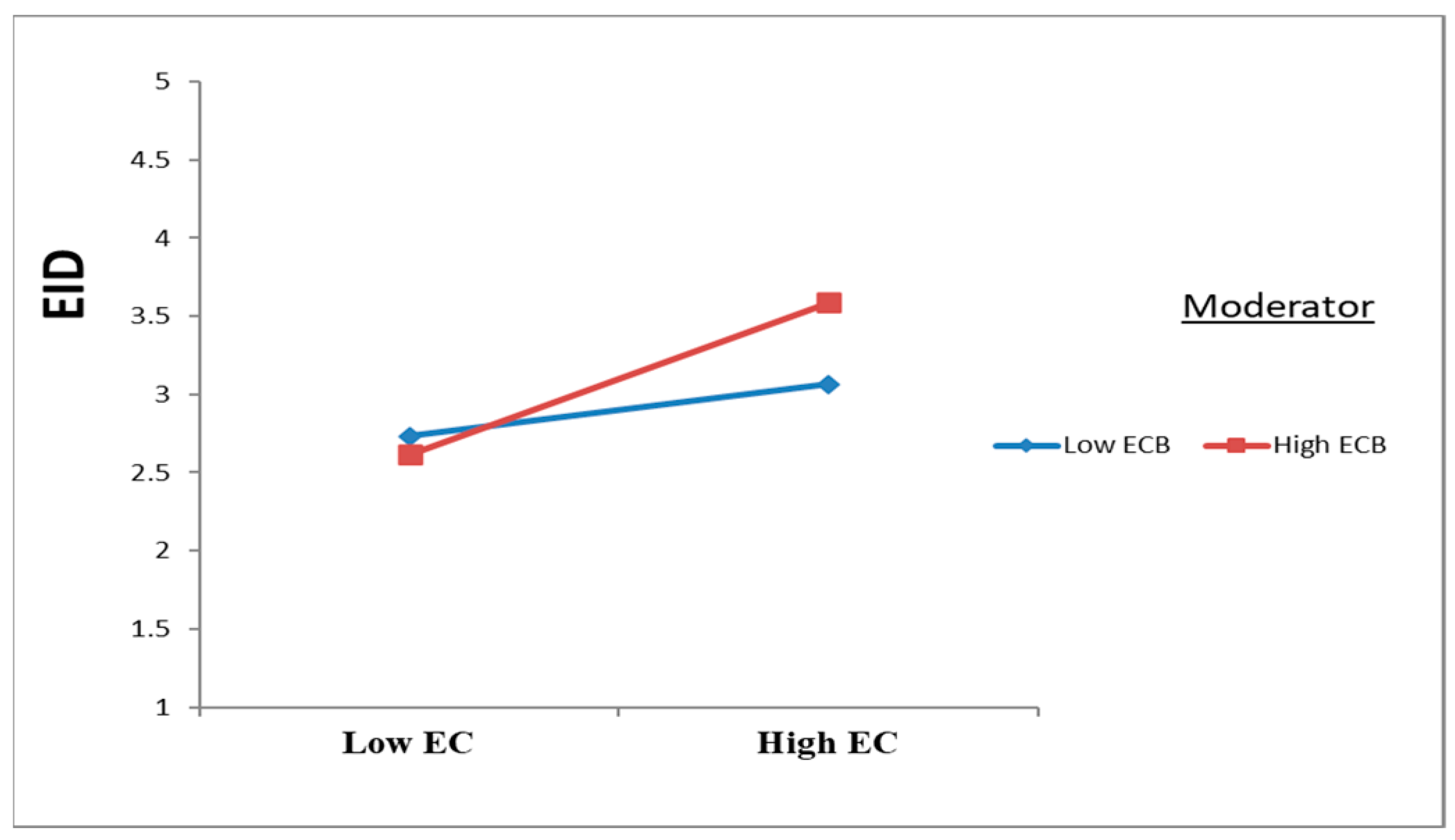

Regarding the moderating Effect,

Table 5 and

Figure 3 demonstrated that ECB moderates the relationship between EC and EID (β = 0.160,

p = 0.012). Specifically, the presence of high levels of ECB strengthens the effect of EC on EID, confirming hypotheses H6a.

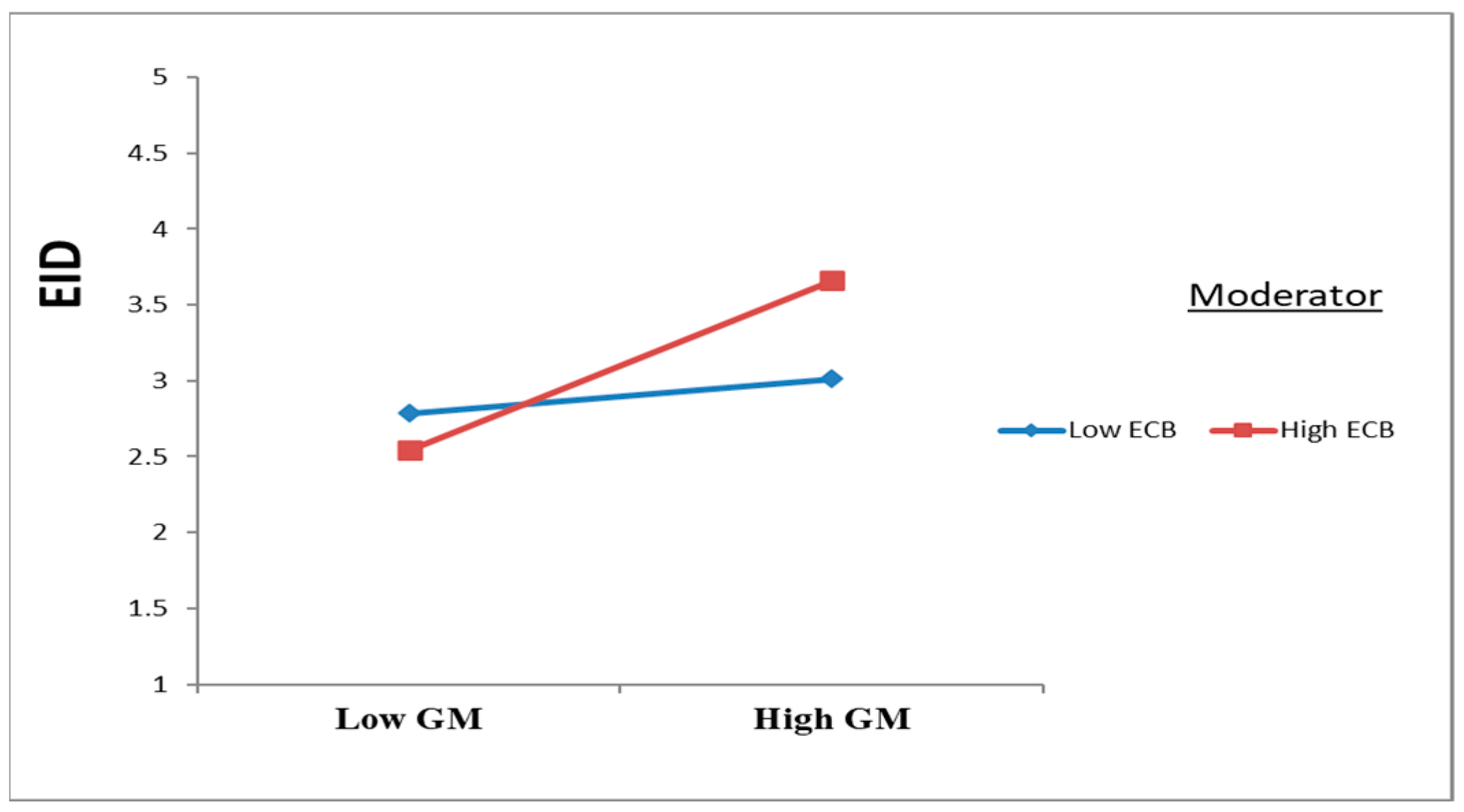

Similarly,

Table 5 and

Figure 4 showed that ECB moderates the relationship between GM on EID (β = 0.222 and

p < 0.01). Specifically, the presence of high levels of ECB strengthens the effect of GM on EID, supporting H6b.

Finally,

Table 5 and

Figure 5 showed that ECB moderates the relationship between EID on GPI (β = 0.133,

p < 0.01). Specifically, the presence of high levels of ECB strengthens the effect of EID on GPI, supporting H6c. However, the moderating effect of the ECB on the relationships between EC and GPI, as well as GM and GPI, was not statistically significant, rendering hypotheses H6d and H6e unsupported.

The study also evaluates the endogenous constructs’ R

2, Cohen’s f

2, and Q

2 values. According to

Cohen (

2013), the f

2 may be “small” (f

2 ≥ 0.02), “medium” (f

2 ≥ 0.15), or “large” (f

2 ≥ 0.35). As

Table 5 shows, the f

2 of the endogenous constructs in this study ranged between “small” and “medium”. Additionally, the R

2 value for environmental identity is 0.355, while the R

2 for green purchasing intention is 0.399. According to (

Cohen, 2013), an R

2 value greater than 0.26 is considered large, provided that it also exceeds the minimum threshold of 0.02 for meaningful explanatory power. Accordingly, the proposed model exhibits an acceptable level of explanatory and predictive power. Furthermore, the Q

2 values exceeded the 0.0 threshold, confirming the model’s predictive power (

Hair et al., 2019).

5. Discussion

Prior studies have highlighted the crucial role of green commitment and motivation in promoting green purchasing intentions. However, the mediating effect of green identity and the moderating role of eco-conscious behavior in enhancing green purchasing behavior remain under-researched (

C. P. Wang et al., 2023). This study indicates this gap by proposing a conceptual context to examine the effect of environmental commitment and green motivation on green purchasing behavior in the existence of environmental identity as a mediator and eco-conscious behavior as a moderator. The study presents findings based on path analysis.

The findings provided evidence that Environmental commitment significantly affects green purchasing intentions and environmental identity, as evidenced by the standardized beta value and significant t-value. This showed that individuals with a distinguished environmental commitment tend to seek accommodation and services that translate their values towards preserving the natural environment, as they perceive themselves as environmentally responsible. This environmental identity, in turn, stimulates their green purchasing intentions, leading them to choose eco-certified hotels and prefer environmentally friendly travel options. This is associated with a study conducted by (

Hojnik et al., 2020).

Blanchard and Paquet (

2023) illustrated the direct significant effect of environmental commitment on environmental identity and green buying intentions.

The study also assessed the effect of green motivation on green identity and green purchasing intentions. The results confirmed the positive effect of green motivation on green identity and green purchasing intentions, as green motivation significantly affects travel experience choices, where eco-conscious travelers seek out sustainable products and services. Tourists who are aware of climate change, pollution, and biodiversity loss develop a stronger environmental identity as individuals prioritize sustainability practices. Moreover, those green motivations reflect travelers’ intentions to book hotels implementing water-saving technologies and waste management strategies. The study’s findings support real-world behavior, showing that green motivation significantly affects both environmental identity and green purchasing intentions, as motivation strengthens environmental identity and leads to buying green options. In addition, there is a significant direct relationship between green identity and green buying intentions. Those findings extend the views of prior studies (

L. Wang et al., 2021;

M. Li & Rabeeu, 2024).

The study provided evidence that environmental identity positively mediates the relationship between green commitment and green purchasing intentions. Also, green motivation and green purchasing intentions. While there is a direct relationship between green commitment, green motivation, and green buying intentions, this relationship could be strengthened by environmental identity as a mediator. This mediating role suggests that environmental identity is essential for promoting green purchasing behavior.

Regarding the non-significant results for hypotheses H6d and H6e, which proposed that ECB moderates the direct relationships between EC → GPI and GM → GPI, it is noteworthy that these hypotheses involve direct paths from independent variables to the outcome variable. The explanation is that the ECB may not be able to directly enhance these relationships without the presence of an intermediary mechanism. In our suggested model, EID serves as a key mediating variable, suggesting that the effect of ECB operates more effectively through enhancing EID, which in turn influences GPI. Therefore, the absence of a significant moderate effect on these direct paths could be attributed to the need for the ECB to act indirectly via EID to reach and impact GPI.

In addition, eco-conscious behavior enhances the positive effect of environmental commitment on environmental identity, green motivation on green identity, and environmental identity on green purchasing intentions as a moderator. Travelers tend to have Eco-conscious behavior that uses reusable products, conserves water or actively chooses sustainable travel options as they commit to environmental sustainability and engage in eco-friendly activities. They are more likely to adopt specific actions as part of their identity. Similarly, eco-conscious behavior strengthens green motivation and environmental identity. Additionally, eco-conscious behavior increases the impact of environmental identity on green purchasing. A traveler who strongly identifies as environmentally conscious is more likely to book stays at sustainable resorts. Furthermore, if tourists participate in environmentally friendly activities, they become even more committed to green purchasing. Those findings are aligned with (

R. Kumar et al., 2023;

Lavuri et al., 2023) research.

The study provided evidence of the non-significant impact of eco-conscious behavior as a moderator on the relationships between environmental commitment and green buying intentions, as well as green motivation and green purchasing intentions, suggesting that eco-conscious behavior may not be a significant factor in strengthening these relationships. This could indicate that individuals’ commitment to environmental values or motivation to adopt sustainable practices may not necessarily need an additional eco-conscious behavior to translate their intentions into actual purchasing behavior.

Moreover, the study findings confirm the effectiveness of the Theory of Planned Behavior (

Ajzen, 1991), specifically regarding the role of internal motivational and identity-based factors in shaping intentions. Hence, green motivation and environmental commitment had the strongest impact on green purchasing behavior as they are both attitude and motivation-driven. The mediating role of green identity highlights the psychological processes by which someone acts on caring for the environment, as emphasized by TPB, internalized values and attitudes shape intention to act. In addition, the moderating role of eco-conscious behavior suggests that even when individuals possess strong green identities, their actual intention to purchase green products is strengthened when they are already engaged in eco-friendly behaviors in daily life.

Additionally, in the tourism and hospitality sector, PLS-SEM has been applied to study the effect of environmental commitment and green motivation on green intentions. (

Jun et al., 2019) used PLS-SEM to study the effect of green motivation and environmental concern on tourists’ willingness to pay a premium for hotel services in China. Their results highlighted the role of personal environmental values and the hotel’s commitment towards sustainability in shaping consumer behavior. In another study conducted by (

C. P. Wang et al., 2023;

Fouad et al., 2025), the consumers’ green intentions to visit green hotels showed that both social norms and personal norms have a positive influence on green purchasing intentions. These studies tend to examine specific constructs in isolation from moderator and mediator constructs. This study expands by integrating environmental identity, environmental commitment and green motivation, analyzed by the PLS-SEM framework, to better understand the extent to which commitment and motivation intertwined shape green purchase intentions in the existence of green identity as a mediator and eco-conscious behavior as a moderator in the context of hospitality.

6. Study Implications

6.1. Theoretical Contributions

The results contribute to the literature on eco-buying behavior by indicating the crucial moderating role of eco-conscious behavior in strengthening the relationships between environmental commitment, green motivation, environmental identity, and green purchasing intentions. Moreover, the study expands on measuring the influence of environmental commitment and environmental motivation on green identity. While previous research has investigated environmental commitment and environmental motivation (

Tekin & Çoknaz, 2022;

He et al., 2021), the current study adds novel value by integrating and measuring the effect of green identity as a mediator and eco-conscious behavior as a moderator, which has not been previously tested in those studies. Moreover, this study filled the theoretical gap by examining the effect of environmental commitment and green behavior on environmental identity. It confirmed that individuals committed to preserving nature with strong green motivations tend to have green identities, as these two factors shape environmental values and identities.

Furthermore, the study is associated with the planned behavior theory, proving the substantial direct relation between environmental commitment and green motivations on green purchasing intentions. Tourists who are devoted to protecting the environment and have strong green motivations, as they prefer to buy green products that reflect their green identity. Also, the study showed the mediating effect of green identity in the link between green commitment and green motivation in increasing green purchasing behavior, as the existence of green identity significantly affects tourists’ choices of green products. The research highlighted how eco-conscious behavior acts as a key moderator. In addition, the study demonstrated how eco-conscious behavior moderates the relation between green motivation, green identity, and green purchasing behavior.

This research tackles the gap in tourism literature, where empirical research on the mediating role of green identity in green purchasing behavior is limited. It also investigates the moderating role of eco-conscious behavior in sustainable tourism purchasing decisions. By applying these theoretical frameworks within the tourism sector, this study provides deeper perceptions into how environmental identity and environmentally conscious travelers form purchasing choices.

6.2. Practical Implications

The research findings offer valuable insights for tourism authorities, hotel executives, and all stakeholders responsible for sustainable tourism development. The relationship between environmental commitment and green motivation on green purchasing behavior in the existence of environmental identity as a mediator and eco-conscious behavior as a moderator offers valuable recommendations for fostering sustainable consumer behavior. Tourism authorities should develop policies encouraging environmental commitment; governments and tourism boards should announce incentive programs for businesses, especially for resorts and hotels that adopt sustainability practices, such as tax reductions for eco-certified hotels or priority promotion for sustainable tourism operators. Also, the tourism authority should implement public awareness campaigns focusing on tourists to foster green choices and encourage them to commit to responsible travel behaviors. Those campaigns could be launched in partnership with influencers and travel bloggers to reinforce the role of eco-conscious behavior in responsible tourism. These campaigns indicate the importance of being involved in eco-friendly activities such as beach clean-ups and waste management workshops. In addition, tourism authorities could collaborate with travel agencies and booking platforms to promote eco-friendly institutions, strengthen their position in the market, and motivate tourists to choose them over non-eco-friendly hotels.

Hotel managers and tourism operators should enhance their environmental identity through branding by integrating their sustainability activities into their brand identity, showcasing eco-friendly initiatives and applications, such as waste reduction strategies, renewable energy, and community engagement activities. Hotels and tourism operators could offer a personalized sustainability experience by providing guided eco-tours and wildlife conservation activities. Those activities could enhance tourists’ environmental identity, making them more committed to sustainable choices. In addition, hotels could leverage eco-conscious behavior to enhance green purchasing intentions by promoting a green loyalty program that rewards guests for choosing eco-friendly services and implementing practices such as reusing towels, reducing food waste, and participating in conservation activities. Furthermore, the hotel’s training department should provide sustainability-focused training for the hotel staff to help them educate guests about how their choices contribute to environmental sustainability, reinforcing green motivation.

Additionally, travel agencies and tour operators should design travel packages encouraging green purchasing intentions, including sustainable accommodation, low-impact activities, and local community engagement. Also, promoting green transportation allows visitors to make more environmentally friendly choices. Travel agencies and tour operators could encourage pro-environmental behavior among travelers by offering discounts to travelers who choose sustainable options, such as train travel over flights, eco-lodges over traditional hotels, and being involved in environmental practices, which can reinforce eco-conscious behavior. Also, promote green travel pledges where tourists commit to environmentally friendly actions before and during their trips, strengthening their environmental identity. Those pledges could be as simple as during my travel, I will separate my waste and moderate the water usage, to more complex pledges engaging in preserving the natural environment, such as beach clean-ups and participating in green workshops.

7. Limitations and Future Research

The study was in Egypt, which limits the generalization of the findings to other regional or global tourism markets, as the data were collected from visitors who stayed in resorts. Five- and four-star hotels in Sharm El-Sheik, Egypt. Future research could use a different sample and include various cultural cities to understand how environmental commitment and green motivation could affect green purchasing behavior in the existence of green identity as a mediator and eco-conscious behavior as a moderator. Future studies are also encouraged to employ multi-group analysis (MGA) based on demographic characteristics (e.g., gender, age, education) to examine potential structural differences across segments. The study primarily examined factors influencing green purchasing intentions, such as environmental commitment and motivation. However, other variables, such as government regulations and marketing influences, could be investigated in future research. While the study assessed the moderating role of eco-conscious behavior and environmental identity as mediators, further research could examine more variables, such as corporate environmental responsibility, economic barriers, pricing factors, social norms, and green trust. In addition, other moderators could be investigated, such as environmental knowledge and social norms. Moreover, the study has employed PLS-SEM for data analysis; future research could employ other methodological tools, such as observational methods or experimental simulations, to address these limitations. Additionally, this study relies on cross-sectional survey data collected at a single point in time, which may introduce common method bias (CMB). Although the study employed procedures to mitigate this bias, future research should consider longitudinal designs and multi-source data to enhance the validity of the findings further.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A.A.A., S.F. and K.A.R.; Methodology, S.F.; Software, S.F.; Validation, H.A.M.A.; Formal analysis, S.F.; Investigation, H.A.M.A.; Resources, K.A.R.; Data curation, S.F. and K.A.R.; Writing—original draft, H.A.M.A. and K.A.R.; Writing—review and editing, A.A.A.A., S.F. and K.A.R.; Visualization, K.A.R.; Supervision, S.F.; Project administration, S.F.; Funding acquisition, H.A.M.A. and A.A.A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study is supported via funding from Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University project number (PSAU/2025/R/1446).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Al-Alson Institute for Tourism and Computer Research Ethics Committee (approval code: 2-4-2024 and date of approval: 2 April 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available upon request from researchers who meet the eligibility criteria. Kindly contact the first author privately through email.

Acknowledgments

The researchers would like to thank the Prince Sattam Bin Abdulaziz University, Saudi Arabia, for financial support (PSAU/2025/R/1446).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Scales of the Study Variables

| Environmental Commitment |

| - I really care about the environmental concerns |

| - I would feel guilty about not supporting the environment |

| - The environmental concerns of the hotel I stay in mean a lot to me |

| - I feel a sense of duty to support the environmental concerns |

| - I feel as if the environmental concerns of the hotel I stay in are mine |

| - I feel personally attracted to the environmental concerns of the hotel I stay in |

| - I feel obligated to support the environmental efforts of the hotel I stay in |

| - I strongly value the environmental efforts of the hotel I stay in |

| Green Intrinsic Motivation |

| - I enjoy accepting new green ideas and products. |

| - I enjoy solving environmental problems through green measures. |

| - I enjoy searching for green products or services that are completely new. |

| - I enjoy giving feedback to improve existing green products or services. |

| - I feel excited when I use green products. |

| Green Extrinsic motivation |

| - I feel motivated by the recognition I earn from people when adopting green products or services. |

| - I often think about discounts, gifts, and prizes when buying green products or services. |

| - I have to feel that I am saving something from my green product purchases |

| - I am concerned about how other people are going to react to me using green products or services. |

| Environmental Identity |

| - I like to spend time outdoors in natural settings (such as mountains, rivers, fields, local parks, beach, or garden) |

| - I think of myself as a part of nature, not separate from it. |

| - If I had enough resources, such as time or money, I would spend some of them to protect the natural environment. |

| - When I am upset or stressed, I can feel better by spending some time outdoors surrounded by nature. |

| - Behaving responsibly toward nature—living a sustainable lifestyle—is important to who I am. |

| - Learning about the natural world should be part of everyone’s upbringing. |

| - If I could choose, I would prefer to live where I can have a view of the natural environment, such as trees or fields. |

| - An important part of my life would be missing if I was not able to get outside and enjoy nature from time to time. |

| - I feel refreshed when I spend time in nature. |

| - I consider myself a steward of our natural resources. |

| - I feel comfortable out in nature. |

| - I enjoy encountering elements of nature, like trees or grass, even when I am in a city setting. |

| Eco Conscious Behavior |

| - It is important to me that the products I use do not harm the environment. |

| - I consider the potential environmental impact of my actions when making many of my decisions. |

| - My purchase habits are affected by my concern for our environment. |

| - I am concerned about wasting the resources of our planet. |

| - I would describe myself as environmentally responsible. |

| - I am willing to be inconvenient to take actions that are more environmentally friendly |

| - I believe environmentally friendly products are important to save our nature. |

| Green Purchasing Intention |

| - I intend to purchase green products/services because of their environmental concern |

| - I expect to purchase green products/services in the future because of their environmental performance. |

| - Overall, I am glad to purchase green products/services because they are environmentally friendly. |

| - I am willing to buy green products/services because of their environmental performance. |

| - I will be willing to pay higher prices for green products/services that are environmentally friendly. |

References

- Ahmad, H., Abidin, S. A., & Quah, W. B. (2024). Eco-consciousness in action: Student perspectives on sustainable packaging. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 14(7), 476–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, F., Ashfaq, M., Begum, S., & Ali, A. (2020). How ‘green’ thinking and altruism translate into purchasing intentions for electronics products: The intrinsic-extrinsic motivation mechanism. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 24, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizan, O., Tajmir Riahi, M., Shahriari, M., & Rasti-Barzoki, M. (2023). The effect of green culture and identity on organizational commitment. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 68(4), 843–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchard, C., & Paquet, M. (2023). Exploring environmental identity at work and at home: A multifaceted perspective. Current Research in Ecological and Social Psychology, 5, 100141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R. W. (1980). Translation and content analysis of oral and written materials. In Methodology (pp. 389–444). Allyn and Bacon. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, S. H. G., & Chau, K. Y. (2021). Cultural differences between Asians and non-Asians affect buying attitudes and purchasing behaviours towards green tourism products. Journal of Service Science and Management, 14(03), 241–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L., Matloob, S., Sunlei, Y., Qalati, S. A., Raza, A., & Limón, M. L. S. (2023). A moderated–mediated model for eco-conscious consumer behavior. Sustainability, 15(2), 897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L., Cui, H., Zhang, Z., Yang, M., & Zhou, Y. (2024). Study on consumers’ motivation to buy green food based on meta-analysis. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 8, 1405787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S., Czellar, S., Nartova-Bochaver, S., Skibins, J. C., Salazar, G., Tseng, Y. C., Irkhin, B., & Monge-Rodriguez, F. S. (2021). Cross-cultural validation of a revised environmental identity scale. Sustainability, 13(4), 2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (2013). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cop, S., Alola, U. V., & Alola, A. A. (2020). Perceived behavioral control as a mediator of hotels’ green training, environmental commitment, and organizational citizenship behavior: A sustainable environmental practice. Business Strategy and the Environment, 29(8), 3495–3508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, P. J., West, S. G., & Finch, J. F. (1996). The robustness of test statistics to nonnormality and specification error in confirmatory factor analysis. Psychological Methods, 1(1), 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawes, J. (2008). Do data characteristics change according to the number of scale points used? an experiment using 5-point, 7-point and 10-point scales. International Journal of Market Research, 50(1), 61–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Tahhan, E. A. K. S. (2023). Environmental awareness of employees as a mediating variable in the relationship between the marketing orientation of green star hotels and sustainable tourism in Egypt. WSEAS Transactions on Business and Economics, 21, 248–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraz, N. A., Ahmed, F., Ying, M., & Mehmood, S. A. (2021). The interplay of green servant leadership, self-efficacy, and intrinsic motivation in predicting employees’ pro-environmental behavior. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 28(4), 1171–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayyad, S. (2020). The role of employee trust in the relationship between leaders’ aggressive humor and knowledge sharing. Journal of Association of Arab Universities for Tourism and Hospitality, 19(1), 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrajão, P., Torres, N., & Martins, A. Q. (2024). Adaptation of the revised environmental identity scale to adult Portuguese native speakers: A validity and reliability study. Sustainability, 16(18), 7877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, S., Pereira, O., & Simões, C. (2023). Determinants of consumers’ intention to visit green hotels: Combining psychological and contextual factors. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 31(3), 535–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouad, A. M., Abdullah Khreis, S. H., Fayyad, S., & Fathy, E. A. (2025). The dynamics of coworker envy in the green innovation landscape: Mediating and moderating effects on employee environmental commitment and non-green behavior in the hospitality industry. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, K., Prideaux, B., & Konar, R. (2024). An exploratory study on tourist perception of green hotels: Empirical evidence from Thailand. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 31(3), 683–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghali-Zinoubi, Z. (2022). Examining drivers of environmentally conscious consumer behavior: Theory of planned behavior extended with cultural factors. Sustainability, 14(13), 8072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, A. H., Malhotra, A., & Segars, A. H. (2001). Knowledge management: An organizational capabilities perspective. Journal of Management Information Systems, 18(1), 185–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravelines, Ž., Banytė, J., Dovalienė, A., & Gadeikienė, A. (2022). The role of green self-identity and self-congruity in sustainable food consumption behaviour. Organizations and Markets in Emerging Economies, 13(2), 336–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulzar, Y., Eksili, N., Koksal, K., Celik Caylak, P., Mir, M. S., & Soomro, A. B. (2024). Who is buying green products? the roles of sustainability consciousness, environmental attitude, and ecotourism experience in green purchasing intention at tourism destinations. Sustainability, 16(18), 7875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 19(2), 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldorai, K., Kim, W. G., Agmapisarn, C., & Li, J. J. (2023). Who We Are and What We Do: The relevance of green organizational identity in understanding environmental performance. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 114, 103574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z., Zhou, Y., Wang, J., Li, C., Wang, M., & Li, W. (2021). The impact of motivation, intention, and contextual factors on green purchasing behavior: New energy vehicles as an example. Business Strategy and the Environment, 30(2), 1249–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hojnik, J., Ruzzier, M., & Manolova, T. S. (2020). Sustainable development: Predictors of green consumerism in slovenia. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 27(4), 1695–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L., Chang, T. W., Lee, Y. S., Yen, S. J., & Ting, C. W. (2023). How does sustainable leadership affect environmental innovation strategy adoption? The mediating role of environmental identity. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(1), 894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X., Khan, S. M., Huang, S., Abbas, J., Matei, M. C., & Badulescu, D. (2022). Employees’ green enterprise motivation and green creative process engagement and their impact on green creative performance. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(10), 5983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibnou-Laaroussi, S., Rjoub, H., & Wong, W. K. (2020). Sustainability of green tourism among international tourists and its influence on the achievement of green environment: Evidence from north Cyprus. Sustainability, 12(14), 5698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilieva, N., & Vasilev, V. (2024). Green human resource management and motivation-innovations, traditions and best practices. Edukacja Ekonomistów i Menedżerów, 71(1), 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasothini, K., Neruja, S., & Arulrajah, A. A. (2023). The effect of environment knowledge and pro-environment psychological climate on environmental citizenship behaviour: The mediating role of environmental commitment. Sri Lankan Journal of Human Resource Management, 13(1), 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaid, Z. K., Khan, K., Kamran, M., & Aslam, S. (2024). Influence of mindfulness on environmental satisfaction among young adults: Mediating role of environmental identity. Environment and Social Psychology, 9(10), 2937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, W., Ali, W., Bhutto, M. Y., Hussain, H., & Khan, N. A. (2019). Examining the determinants of green innovation adoption in SMEs: A PLS-SEM approach. European Journal of Innovation Management, 24(1), 67–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kautish, P., & Sharma, R. (2020). Determinants of pro-environmental behavior and environmentally conscious consumer behavior: An empirical investigation from emerging market. Business Strategy & Development, 3(1), 112–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keles, H., Yayla, O., Tarinc, A., & Keles, A. (2023). The effect of environmental management practices and knowledge in strengthening responsible behavior: The moderator role of environmental commitment. Sustainability, 15(2), 1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khairy, H. A., Fayyad, S., & El Sawy, O. (2025). AI awareness and work withdrawal in hotel enterprises: Unpacking the roles of psychological contract breach, job crafting, and resilience. Current Issues in Tourism, 1–21, Advanced online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatter, A. (2023). Challenges and solutions for environmental sustainability in the hospitality sector. Sustainability, 15(15), 11491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krejcie, R. V., & Morgan, D. W. (1970). Determining sample size for research activities. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 30(3), 607–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R., Kumar, K., Singh, R., Sá, J. C., Carvalho, S., & Santos, G. (2023). Modeling environmentally conscious purchase behavior: Examining the role of ethical obligation and green self-identity. Sustainability, 15(8), 6426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S., & Yadav, R. (2021). The impact of shopping motivation on sustainable consumption: A study in the context of green apparel. Journal of Cleaner Production, 295, 126239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavuri, R., Roubaud, D., & Grebinevych, O. (2023). Sustainable consumption behaviour: Mediating role of pro-environment self-identity, attitude, and moderation role of environmental protection emotion. Journal of Environmental Management, 347, 119106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L., Bibi, M., Hussain, Y., & Xiao, D. (2025). Examining sustainable hospitality practices and employee turnover in Pakistan: The interplay of robotics awareness, mutual trust, and technical skills development in the age of artificial intelligence. Journal of Environmental Management, 373, 123922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M., & Rabeeu, A. (2024). How corporate social responsibility motivation drives customer extra-role behavior and green purchase intentions: The role of ethical corporate identity. Sustainability, 16(13), 5611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W., Bhutto, T. A., Xuhui, W., Maitlo, Q., Zafar, A. U., & Bhutto, N. A. (2020). Unlocking employees’ green creativity: The effects of green transformational leadership, green intrinsic, and extrinsic motivation. Journal of Cleaner Production, 255, 120229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Likert, R. (1932). A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Archives of Psychology, 22(140), 55. [Google Scholar]

- Lou, X., & Li, L. M. W. (2021). The relationship between identity and environmental concern: A meta-analysis. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 76, 101653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matell, M. S., & Jacoby, J. (1972). Is there an optimal number of alternatives for Likert-scale items? Effects of testing time and scale properties. Journal of Applied Psychology, 56(6), 506–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, A. Y. C., Hao, G. S., & Carter, S. (2021). Intertwining corporate social responsibility, employee green behavior, and environmental sustainability: The mediation effect of organizational trust and organizational identity. Economics, Management, and Financial Markets, 16(2), 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassani, A. A., Yousaf, Z., Grigorescu, A., & Popa, A. (2023). Green and environmental marketing strategies and ethical Consumption: Evidence from the tourism sector. Sustainability, 15(16), 12199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, P. M., Cheung, C. T., Lit, K. K., Wan, C., & Choy, E. T. (2024). Green consumption and sustainable development: The effects of perceived values and motivation types on green purchase intention. Business Strategy and the Environment, 33(2), 1024–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, V., Waters, C., Oloyede, O. O., & Lignou, S. (2022). Exploring consumers’ understanding and perception of sustainable food packaging in the UK. Foods, 11(21), 3424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowacki, M., Chawla, Y., & Kowalczyk-Anioł, J. (2021). What drives the eco-friendly tourist destination choice? The Indian perspective. Energies, 14(19), 6237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J. C. (1994). Psychometric theory 3E. McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Patwary, A. K. (2023). Examining environmentally responsible behaviour, environmental beliefs and conservation commitment of tourists: A path towards responsible consumption and production in tourism. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 30(3), 5815–5824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63(1), 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rashwan, K. (2019). The Role of virtual museums in preserving protected areas: The case of wadi Degla virtual museum. Journal of Association of Arab Universities for Tourism and Hospitality, 17(3), 18–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, A., Farrukh, M., Iqbal, M. K., Farhan, M., & Wu, Y. (2021). Corporate social responsibility and employees’ voluntary pro-environmental behavior: The role of organizational pride and employee engagement. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 28(3), 1104–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Román-Augusto, J. A., Garrido-Lecca-Vera, C., Lodeiros-Zubiria, M. L., & Mauricio-Andia, M. (2022). Green marketing: Drivers in the process of buying green products—The role of green satisfaction, green trust, green Wom and green perceived value. Sustainability, 14(17), 10580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, M. A., Eagle, L., & Low, D. (2021). Determinants of eco-socially conscious consumer behavior toward alternative fuel vehicles. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 38(2), 211–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, I. E., Elbaz, A. M., Al-Alawi, A., Alkathiri, N. A., & Rashwan, K. A. (2022). Investigating the role of green hotel sustainable strategies to improve customer cognitive and affective image: Evidence from PLS-SEM and FsQCA. Sustainability, 14(6), 3545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salleh, M. Z. M., Said, A. M., Bakar, E. A., Ali, A. M., & Zakaria, I. (2016). Gender differences among hotel guest towards dissatisfaction with hotel services in Kuala Lumpur. Procedia Economics and Finance, 37, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salsabila, P., & Hartono, A. (2023). The effect of green self identity, self-congruity, perceived value on bioplastic product purchase intention. International Journal of Research in Business and Social Science, 12(1), 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraiva, A., Fernandes, E., & von Schwedler, M. (2020). The green identity formation process in organic consumer communities: Environmental activism and consumer resistance. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, 23(1), 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, D., Priatna, F., & Adhariani, D. (2023). Paid attention but needed support: Environmental awareness of indonesian msmes during pandemic. Business Strategy & Development, 6(4), 624–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmin, S., Shahin, A., & Hasan, M. F. (2024). Influence of socio-demographic and psychological factors on shaping farmers’ pro-environmental behavior in dinajpur, bangladesh. Asia-Pacific Journal of Regional Science, 8(4), 1017–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., Smith, D., Reams, R., & Hair, J. F. (2014). Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM): A Useful Tool for Family Business Researchers. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 5(1), 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehawy, Y. M., & Ali Khan, S. M. F. (2024). Consumer readiness for green consumption: The role of green awareness as a moderator of the relationship between green attitudes and purchase intentions. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 78, 103739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silintowe, Y. B. R., & Sukresna, I. M. (2023). Understanding green self-identity: Does it affect green buying behavior? social identity theory perspective. Scientific Papers of the University of Pardubice, Series D: Faculty of Economics and Administration, 31(1), 1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X., Tian, Z., Wang, J., & Su, W. (2022). The impact of environmental commitment on green purchase behavior in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(14), 8644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavitiyaman, P., Zhang, X., & Chan, H. M. (2024). Impact of environmental awareness and knowledge on purchase intention of an eco-friendly hotel: Mediating role of habits and attitudes. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, 7(5), 3148–3166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teeroovengadum, V. (2019). Environmental identity and ecotourism behaviours: Examination of the direct and indirect effects. Tourism Review, 74(2), 280–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekin, N., & Çoknaz, D. (2022). The role of environmental concern in mediating the effect of personal environmental norms on the intention to purchase green products: A case study on outdoor athletes. ReMark-Revista Brasileira de Marketing, 21(4), 1282–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, F., Iraldo, F., Vaccari, A., & Ferrari, E. (2015). Why eco-labels can be effective marketing tools: Evidence from a study on italian consumers. Business Strategy and the Environment, 24(4), 252–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Y., Zhu, Z., Chen, W., Wang, F., Hu, X., & Wang, J. (2023). Knowledge, attitudes and practice regarding environmental friendly disinfectants for household use among residents of china in the post-pandemic period. Frontiers in Public Health, 11, 1161339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C. P., Zhang, Q., Wong, P. P. W., & Wang, L. (2023). Consumers’ green purchase intention to visit green hotels: A value-belief-norm theory perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1139116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L., Wang, Z. X., Wong, P. P. W., & Zhang, Q. (2021). Consumer motivations, attitude and behavioral intention toward green hotel selection. Journal of Tourism, Culinary, and Entrepreneurship (JTCE), 1(2), 79–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L., Wong, P. P. W., & Narayanan Alagas, E. (2020). Antecedents of green purchase behaviour: An examination of altruism and environmental knowledge. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 14(1), 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L. H., Ho, J. L., Yeh, S. S., & Huan, T. C. T. (2022). Is robot hotel a future trend? exploring the incentives, barriers and customers’ purchase intention for robot hotel stays. Tourism Management Perspectives, 43, 100984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., Van der Werff, E., Bouman, T., Harder, M. K., & Steg, L. (2021). I am vs. we are: How biospheric values and environmental identity of individuals and groups can influence pro-environmental behaviour. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 618956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, H., & Azmi, F. T. (2024). Workplace pro-environmental behaviour: A review and bibliometric analysis. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 73(1), 158–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C., Ma, X., & Liu, L. (2023). The effect of passion for outdoor activities on employee well-being using nature connectedness as the mediating variable and environmental identity as the moderating variable. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 16, 4883–4896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).