1. Introduction

Effective leadership is critical for achieving organizational success and promoting employee engagement in today’s dynamic and brutally competitive corporate environment (

Salameh-Ayanian et al., 2025;

Yanting & Wareewanich, 2024). The ability to transform individuals, teams, and entire organizations exists within the various leadership styles, with transformational leadership emerging as a significant and powerful strategy (

Kopackova et al., 2024;

Jabbour Al Maalouf et al., 2025). Transformational leadership is a leadership style characterized by the ability to instigate and motivate followers to surpass their self-interests for the good of the organization. This can include behaviors such as providing a clear vision, nurturing an environment of intellectual stimulation, and offering individualized support to followers (

Al Maalouf & El Achi, 2023). Transformational leadership has attracted a lot of interest from academics and practitioners due to its emphasis on inspiration, vision, and intellectual stimulation (

Muliati et al., 2022;

Zadok et al., 2024). Transformational leaders are capable of compelling subordinates to put the establishment’s interests ahead of their ones (

Lewa et al., 2022), enhancing collaboration trust, and overall organizational performance (

Guo & Zhang, 2024). Many studies have found a positive relationship between this leadership style and organizational outcomes such as increased employee satisfaction, commitment, and performance (

Asgari et al., 2020;

Huynh & Hua, 2020;

Iriani et al., 2023;

Liu et al., 2024;

Ly, 2024;

Nanjundeswaraswamy, 2023;

Muliati et al., 2022). Transformational leaders have been found to foster an environment that encourages innovation, creativity, and adaptability (

Alateeg & Alhammadi, 2024). Moreover, transformational leaders have been recognized for their ability to develop and nurture future leaders within their organizations they invest in the growth and development of their followers (

Malik & Malik, 2023).

The work environment is the physical and psychological conditions in which employees operate, including aspects such as the availability of resources and overall organizational culture. Many studies discussed the impact of the work environment on performance and found a positive impact (

Andrianto et al., 2023;

Dreer, 2024;

Guerra et al., 2024;

Iskandar et al., 2023;

Laily & Wahyuni, 2023;

Nugroho et al., 2023;

Onikoyi, 2024;

Sutaguna et al., 2023;

Tannady & Budi, 2023).

Recent studies on transformational leadership and work environment in educational settings have demonstrated its positive impact on teacher performance, yet some complexities and gaps remain.

Siswanto et al. (

2023) and

Vitria et al. (

2021) found that both transformational leadership and work environment positively impact teacher performance, suggesting that leadership style and environmental factors are vital for educational success. Similarly,

Hakim et al. (

2023) demonstrated that transformational leadership significantly improves teacher performance and satisfaction, although the work environment did not directly impact teacher performance.

Mansor et al. (

2021) showed that transformational leadership strengthens teachers’ trust and commitment, while

Y. D. Lee and Kuo (

2019) emphasized its positive correlation with teacher motivation.

Jabbar et al. (

2020) further identified a strong link between transformational leadership, organizational commitment, work environment, and job satisfaction among teachers.

Sirait (

2021) corroborated these findings, showing that transformational leadership positively influences work culture, work environment, and teacher performance, with the work environment enhancing performance as well.

These studies were conducted in stable contexts. Despite their findings, limited research addresses the interaction between transformational leadership and the work environment in crisis-prone, challenging environments, such as Lebanon. Lebanon’s educational sector is facing ongoing turmoil, including economic instability and political challenges, which creates a unique and urgent need to understand effective leadership and environmental support within this context. This study seeks to fill this gap by exploring the combined impact of transformational leadership and work environment on teacher performance within the challenging educational landscape amid Lebanon’s ongoing turmoil (

Jabbour Al Maalouf et al., 2024). By focusing on educational settings under these difficult conditions, this research contributes new insights into the effectiveness of transformational leadership and work environment factors and highlights adaptive practices for educational administration in crisis contexts.

Thus, the research objectives are to examine the effect of transformational leadership on teacher performance, assess the impact of the work environment on teacher performance in crisis-affected educational settings, and investigate the moderating role of the work environment in the relationship between transformational leadership and teacher performance.

The significance of this study lies in its two-fold contribution to both theory and practice within the field of educational leadership. Theoretically, it enriches existing literature by examining the interplay between transformational leadership and work environment factors within crisis-affected educational settings, with a particular focus on the moderating role of the work environment. By addressing a critical research gap, namely, the limited exploration of these dynamics in challenging environments like Lebanon, the study provides valuable insights into how these factors function under crisis conditions. This perspective is essential for refining transformational leadership theories to better account for situational complexities, particularly in contexts where conventional leadership practices may not yield expected outcomes. Practically, the study’s findings offer crucial implications for educational leaders and policymakers in Lebanon and other crisis-prone regions. A deeper understanding of the relationship between transformational leadership, the work environment, and teacher performance—particularly the moderating effect of the work environment—can inform the development of targeted strategies that enhance teacher performance and well-being. By fostering a more supportive and resilient educational environment, these insights can contribute to sustaining teaching effectiveness despite ongoing challenges.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Transformational Leadership

The notion of leadership relates to one’s or a group’s capacity to lead, direct, and influence others toward a common objective or vision (

Kilag et al., 2024). Leadership involves the process of inspiring and motivating others to collaborate while utilizing their talents and skills to accomplish common goals effectively and efficiently (

Maker, 2021;

Van De Mieroop et al., 2020). Transformational leadership practices refer to a set of specific actions that leaders do to raise the effectiveness and productivity of their companies as a whole (

B. M. Bass & Riggio, 2006). Transformational leaders display flawless effects, stimulating inspiration, personalized deliberation, and intellectual encouragement in their regular interactions with the team or subordinates (

B. M. Bass & Riggio, 2006). According to

Velcu-Laitinen (

2024), leaders must inspire their followers to embrace novel perspectives and behaviors, as well as reconsider principles to pique their intellectual curiosity. Transformational leadership is the epitome of perfect influence; it provides guidance and a sense of purpose while exhibiting unwavering commitment to those objectives (

Ahsan, 2024). Those practices have a big and growing impact on followers and subordinates in organizations (

Bakker et al., 2023).

A transformational leader motivates their people to put aside their personal interests in favor of the success of the company (

Løvaas et al., 2020). They are capable of persuading followers to put in a lot of work to attain common goals (

Amet & Kurnia, 2023) and are aware of the need for self-improvement in their followers (

Arikan, 2020;

Hussein et al., 2022). Transformational leadership makes the need for change obvious, creates a fresh vision, inspires dedication to putting it into practice, and changes followers on an individual and group level (

J. Lee & Gachon, 2023). Idealistic influence, intellectual stimulation, personal considerations, and inspirational commitment are the four characteristics of transformative leadership. A transformational leader encourages his followers to continually explore creative ways to finish tasks by offering challenges and questions, which helps his followers increase their level of competence. The supporters see work as a place to consistently hone skills and cultivate an obstinate and rough mentality, as opposed to just doing it out of habit.

Numerous studies have affirmed the positive impact of transformational leadership on teacher performance (

Muliati et al., 2022;

Bakker et al., 2023). These works underscore how leaders who display idealized influence, intellectual stimulation, individualized consideration, and inspirational motivation can cultivate greater motivation, job satisfaction, and professional growth among educators. In particular,

Vitria et al. (

2021) highlight the principal’s role in shaping a school culture that enhances teacher morale and performance. Furthermore,

Kant and Asefa (

2022) argue that transformational leaders have a critical role in influencing and improving work performance by enhancing job satisfaction and promoting innovative behavior. Transformational leaders improve school culture and, therefore, teachers’ performance (

Asad et al., 2022). A positive school culture enhances teachers’ job motivation, which positively affects the work environment and consequently increases teachers’ performance (

Andriani et al., 2018;

Sudibjo & Nasution, 2020).

Sirait (

2021) confirms the positive correlation as well between transformational leadership, culture, work environment, and teacher effectiveness in public high schools. Effective principal leadership has been shown to improve work culture, atmosphere, and performance. However, much of the existing literature is grounded in relatively stable and well-resourced educational systems. These studies often assume the availability of institutional support, consistent funding, and manageable stress levels. In contrast, leadership in fragile or crisis-prone environments presents different challenges. The question remains whether transformational leadership, which largely emphasizes motivation and vision, can sustain performance when structural instability, low morale, and material scarcity dominate the workplace. The current literature lacks a deeper interrogation of these contextual differences, especially in prolonged crisis settings.

Despite its documented effectiveness, transformational leadership may face limitations in environments marked by persistent stress and resource scarcity, such as Lebanon’s educational sector. Scholars have noted that transformational leadership, while inspirational, can sometimes neglect practical constraints like burnout, institutional disorganization, and chronic underfunding (

Keil, 2020;

Kelly & Hearld, 2020). These limitations raise important questions about its applicability in sustained crisis conditions and warrant further critical engagement when applied outside stable or well-resourced settings. To address these concerns, complementary leadership theories may offer additional insight. Servant leadership, for instance, prioritizes the well-being and growth of followers by fostering trust, empathy, and ethical stewardship (

Eva et al., 2019). In contrast, adaptive leadership emphasizes the leader’s capacity to guide organizations through uncertainty and systemic disruption by enabling teams to confront challenges and adapt behavior (

Sott & Bender, 2025). These approaches may enrich the understanding of leadership effectiveness in fragile educational systems and serve as valuable extensions to the transformational model in future research.

2.2. Educational Leadership

Educational leadership can be defined as one of the most vital elements of educational administration (

Rheaume, 2024;

Leithwood, 2021). The educational leader in the educational field refers to anyone who engages in directing, coordinating, planning, and evaluating the activities and initiatives of administrative and educational personnel, working towards attaining the goals of the educational institution (

Forfang & Paulsen, 2024;

Kilag et al., 2024).

An educational leader’s responsibility extends beyond simply ensuring that an organization operates within the legal bounds; it goes further to explicitly offer the leaders motivations and rewards that promote activity, build a spirit of cooperation, and promote a sense of partnership among them (

Unger & Sann, 2023).

Day et al. (

2020) identify five groups of capabilities needed by any school leader which are human skills defined as the ability to understand themselves, and the team members they work with, information-related skills which enable them to receive, monitor, store, retrieve, and utilize information to achieve educational institution objectives, decision-making skills which help them in making more efficient decisions, technical skills allowing them to manage tasks in a specialized field(s), and intellectual skills allowing leaders to see the overall picture of educational plans, outcomes, and actions results.

While most leadership models emphasize planning, coordination, and technical skills, recent research from the MENA region highlights the adaptive, moral, and contextually responsive dimensions of educational leadership under crisis.

Arar and Massry-Herzallah (

2019) describe the challenges of managing a school in refugee camps, where leaders must balance limited resources, political instability, and cultural tensions while maintaining institutional function and morale. Similarly,

Örücü et al. (

2021) examine how school principals in Lebanon, Turkey, and Germany confront post-migration challenges, employing flexible and community-oriented leadership strategies to address instability and social fragmentation. These results suggest that educational leadership in fragile or transitional contexts often requires hybrid approaches that blend transformational vision with adaptive and servant-like responsiveness to crisis realities.

2.3. Work Environment

The workplace is seen as a significant aspect of how well leaders execute because it influences motivation, loyalty to their organizations, and concern for things touched by transformational leadership and work (

Kao et al., 2023;

Al Maalouf et al., 2023). It includes every element that lowers turnover. Such leaders inspire followers by taking into account their particular needs and goals, which has an impact on the trust level in the connection. They achieve this through promoting followers’ loyalty to their causes and businesses. They also concur that to increase productivity, firms should design work that takes into account the unique environmental requirements of each individual (

Kao et al., 2023).

Without a doubt, one of the most important aspects of an instructor’s job is their work environment, which has a big influence on output. According to

Pradipto and Ibrahim (

2022), the two main categories of work environments are physical and non-physical work environments. Work surroundings, whether physical or virtual, can both improve and significantly affect instructors’ performance. A bad work environment can reduce performance, whereas a good work environment is better for increasing it (

Hartinah et al., 2020;

Heidari et al., 2024;

Sugiarti, 2022;

Sutaguna et al., 2023). Motivation and the effectiveness of instructors have a big impact on work, therefore the higher the motivation at work, the better the effectiveness of teachers (

Sliwka et al., 2024). Finally, an improved work environment enhances teacher performance, which in turn facilitates the achievement of educational objectives and contributes to shaping well-rounded, competent individuals equipped for societal and professional challenges.

2.4. Research Context

The Lebanese educational system has faced significant challenges in recent years, primarily due to the ongoing economic, political, and social turmoil in the country. The Lebanese crisis, which began in 2019, has severely impacted various sectors, including education (

Al Maalouf et al., 2023). The devaluation of the Lebanese pound, inflation, and increasing unemployment rates have led to a financial strain on educational institutions. This has resulted in salary reductions for teachers, shortages in educational materials, and a decline in the overall quality of education (

Al Maalouf & Al Baradhi, 2024). Additionally, political instability and the erosion of trust in governmental institutions have created an environment where teachers face heightened stress and uncertainty in their professional roles.

While extensive research has highlighted the positive impacts of transformational leadership on teacher performance and the work environment in more stable contexts, there remains a significant gap in the literature regarding how these dynamics operate within crisis-prone environments, particularly in Lebanon’s education sector. The country faces unique challenges due to ongoing economic instability, political unrest, and resource constraints, creating a high-stress environment for both educational leaders and teachers (

Kontar et al., 2025). In such settings, leadership must do more than inspire; it must adapt to uncertainty, compensate for institutional gaps, and promote resilience among demoralized staff.

Recent research from the MENA region provides relevant parallels to Lebanon’s educational crisis (

Arar & Massry-Herzallah, 2019;

Örücü et al., 2021). Educational governance across Arab countries is shaped by persistent socio-political disruptions and centralized state control, calling for more contextually responsive models of leadership that account for institutional fragility and cultural diversity.

Thus, in the face of these adversities, it becomes even more crucial for school leaders to adopt leadership styles that promote resilience and performance in their teachers. Transformational leadership, known for its ability to inspire and motivate individuals toward achieving collective goals, may play a significant role in fostering positive outcomes in times of crisis. However, the interaction between transformational leadership and the work environment, as well as their combined effects on teacher performance, remains largely unexplored in the context of Lebanon’s educational landscape.

This gap in research is particularly pressing given the need for effective leadership and environmental support for Lebanese teachers to maintain performance and motivation in the face of ongoing crises. Lebanon’s educational system requires leadership that not only inspires but also creates a conducive environment for teachers to thrive, despite external turmoil. The ongoing economic hardships, coupled with the political instability and resource scarcity, underscore the importance of understanding the factors that can drive teacher performance under such conditions. Thus, this study seeks to fill this gap by examining the joint impact of transformational leadership and work environment factors on teacher performance in Lebanon’s unique educational landscape. By focusing on the combined role of these factors, this research aims to shed light on how educational leaders can enhance teacher performance even amid crises.

2.5. Conceptual Model

Based on the aforementioned gap and prior research findings, the hypotheses of the study are as follows:

H1. Transformational leadership has a positive impact on teacher performance in Lebanese schools amid ongoing turmoil.

H2. Work environment has a positive impact on teacher performance in Lebanese schools amid ongoing turmoil.

H3. Work environment moderates the relationship between transformational leadership and teacher performance in Lebanese schools amid ongoing turmoil.

The relationship between the variables is illustrated in

Figure 1. Transformational leadership (TL) serves as the primary independent variable, while the work environment (WE) functions both as a secondary independent variable and as a mediator. Teacher performance (TP) is the dependent variable. Specifically, the model examines the direct effects of TL and WE on TP, as well as the moderating role of WE on the relationship between TL and TP.

3. Methodology

The mono-method quantitative approach for this research focuses on the collection and analysis of numerical data to inspect the relationships between the variables of the study. This method is mainly well-suited for this study as it allows for precise measurement of the variables, facilitating the identification of statistical relationships. By employing rigorous statistical techniques, the research enhances the reliability and validity of the findings, allowing for generalization to a broader population. The clarity and precision inherent in quantitative data also streamline the analysis process, ensuring that the results are clearly articulated. Additionally, the use of this method aligns with previous studies that have explored similar variables, reinforcing its relevance and applicability. Ultimately, this method offers a comprehensive understanding of the interplay between the studied variables in the context of crisis-affected educational settings in Lebanon.

For data collection, a survey was designed since it allows the collection of standardized data from a large number of participants. It contains four sections.

Section 1 includes demographic data which provides contextual information.

Section 2 included Likert scale statements related to transformational leadership, where the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ-5X) developed by

B. Bass and Avolio (

2004) was adapted to measure five key dimensions of transformational leadership: idealized attributes, idealized behaviors, inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation, and individual consideration. The adaptation process involved modifying the wording of certain items to better align with the educational context of Lebanese schools. Specifically, references to corporate leadership and organizational teams were adjusted to reflect school leadership and teacher interactions. The adapted version was pretested to ensure clarity, relevance, and reliability in the study context. To assess the work environment, the Work Environment Scale (WES) developed by

Moos (

1981) was adapted. The WES measures various dimensions of the work environment, including involvement, peer cohesion, supervisor support, autonomy, task orientation, work pressure, clarity, managerial control, innovation, and physical comfort. This instrument has been widely used across different organizational settings, including educational institutions, to evaluate employees’ perceptions of their work environment. In this study, certain items were modified to better reflect the specific context of Lebanese schools. For example, references to “management” were adjusted to “school administration” to ensure relevance and clarity for the respondents. These adaptations were made to maintain the instrument’s validity while ensuring its applicability to the specific research context. Finally,

Section 4 encompasses teaching performance. In the context of the Lebanese educational system amidst crisis, teacher performance is operationalized as a multi-dimensional construct that includes not only the standard metrics of meeting academic objectives but also adaptability, commitment to professional growth, effective classroom management, and responsiveness to student diversity, which become even more critical during periods of educational disruption. Each variable is operationalized through specific items rated on a Likert scale, enabling quantification and subsequent analysis.

This questionnaire allows for a comprehensive assessment of the relationships between transformational leadership, work environment, and teacher performance from the perspective of teachers within the school system. Before administering the survey to the main participants, a pilot test was conducted on a small group of teachers to identify any latent issues with the questionnaire, such as clarity, relevance, or ambiguity. Feedback was used to enhance and finalize the survey.

The time horizon is cross-sectional since data on transformational leadership practices and teacher performance are collected from the participants at a single point in time, providing a conclusion of their perceptions and experiences. Cross-sectional studies are commonly used for quick assessments and to understand the present situation but may not capture changes or trends over time.

Teachers from different academic schools, including public and private schools in Lebanon, and different teaching levels (cycle 1, cycle 2, cycle 3, high school), participated. As per the World Bank, the number of teachers in Lebanon was 35,937 in 2022 (

Trading Economics, 2024). Thus, as per Qualtrics guidelines, the reliable sample size with a 5% margin error is 381. To ensure broad representation across different types of schools and teaching levels, a random sampling method was applied. A total of 600 questionnaires which were uploaded on Google Forms were distributed to teachers via WhatsApp, email, and social media platforms, achieving a response rate of 84%, resulting in a final sample of 509 teachers. Efforts were made to ensure consistency across participants by using a standardized digital format and distributing the survey through multiple channels simultaneously. Ethical considerations, including informed consent, confidentiality, and voluntary participation, were strictly observed to respect participants’ rights and privacy throughout the research process.

The data collected was analyzed using the SMART PLS 4 software. Data cleaning procedures to handle missing values or outliers were performed. No missing values or outliers were identified. The analysis process included multiple statistical techniques to rigorously assess the measurement and structural models. Descriptive statistics were first conducted to summarize the sample profile, covering the school sector, gender, age, years of experience, and teaching level of participants. For the measurement model, convergent and discriminant validity were examined using several indicators. Reliability was evaluated through Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability. Factor loadings and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) were assessed, with AVE scores above 0.5 demonstrating adequate convergent validity. For discriminant validity, the Fornell–Larcker criterion and the Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) were used. Collinearity was examined using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values for both the inner and outer models. For the structural model, the R-square value was calculated to assess the variance explained by the model/ Hypothesis testing was performed by examining t-statistics and p-values to evaluate the significance of the hypothesized relationships.

It is acknowledged that structural equation modeling (SEM) assumes linear relationships between variables, which may not capture non-linear effects in the data. Additionally, cross-sectional data limits causal inferences, and future longitudinal research could provide further validation.

4. Findings

4.1. Sample Profile

Table 1 shows the sample profile. Regarding the school sector, 54.4% of the respondents were from private schools and 45.6% were from public schools. Regarding gender, 49.1% were male and 50.9% were female. Also, 17.7% of the respondents were under 25 years old, 19.3% were between 25 and 30 years old, 30.3% were in the 30–35 age group, 29.5% were aged between 35 and 40 and only 3.3% were above 40 years old. Regarding years of experience, 5.1% have less than 2 years of experience, 16.1% have 2–5 years of experience, 25.9% have 5–10 years of experience and 52.5% have more than 10 years of experience. Lastly, regarding the teaching level, 21.0% taught in cycle 1, 22.8% in cycle 2, 27.3% in cycle 3, and 28.9% in high school.

4.2. Descriptive Statistics

Table 2 shows that the missing values are zero for all the questions. It also shows the mean and standard deviation for each.

4.3. Reliability and Validity

Regarding the convergent validity assessment, the Reliabilities Coefficients, Factor loadings, and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) show internal correlation for each of the dependent variables constructs, which shows that the items measuring the variables have strong coherence. Based on multicollinearity analysis, no multicollinearity issues were found.

As shown in

Table 3, Cronbach’s alpha is higher than 0.7 for all variables, and so are the composite reliability (rho_a) and (rho_c). As for AVE, the coefficient is higher than 0.5, which also shows high construct reliability.

Even though the factor loadings for a few items are lower than 0.4, there is no need to exclude them from the model given that the convergent validity assessment is positive.

As for the Discriminant Validity assessment using the Fornel Larker method, Cross Loading and Hetotrait–Monotrait Ratio (HTMT).

Using the Fornel-Larker method, the discriminant validity is established which means that the latent variables are not correlated as seen in

Table 4.

As for the Hetotrait–Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) in

Table 5, assuming the complete model, the HTMT between the variables WE and TL was higher than 8.5. This means there is the presence of discriminant validity issues, consulting the cross-loading coefficients.

It shows that item WE4 is causing the discriminant validity issue, so it was excluded from the model, the issue was not solved, which led to repeating the testing. WE5 was then excluded.

The results in

Table 6 show the absence of discriminant validity issues as the HTMT is now below 0.85.

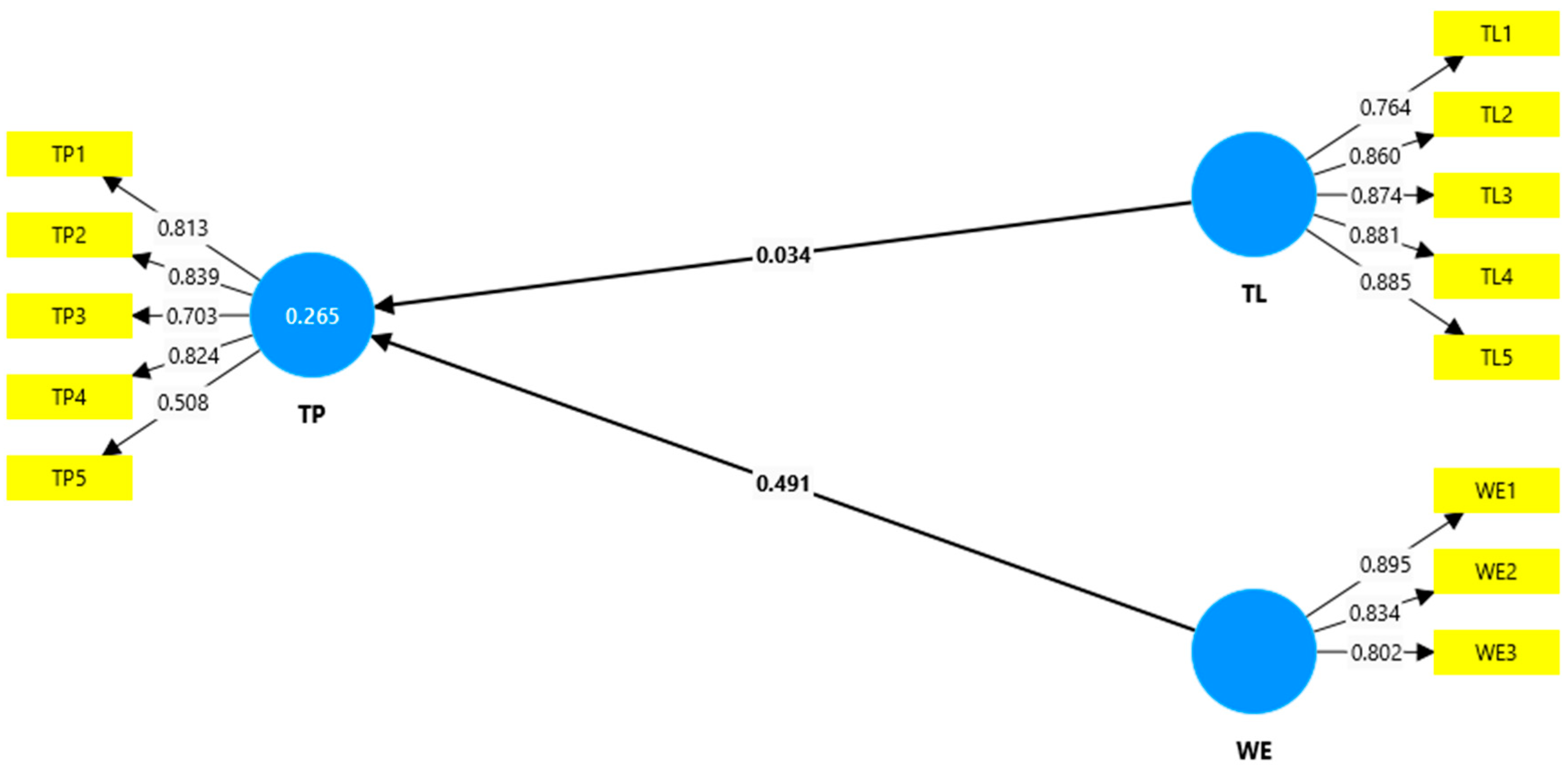

4.4. Measurement Model

Figure 2 shows the measurement model, showing the latent variables (TL, WE, and TP) and their respective observed indicators. All items exhibit sufficient factor loadings, confirming the model’s convergent validity.

4.5. The Structural Model Quality Criteria

The model R-square in

Table 7 is 26.2% > 25% which shows that it is acceptable and that 26.2% of the variations in the independent variables are causing the dependent variable variation.

As for the collinearity tests in

Table 8, the outer and inner model VIF statistics are lower than 4, which shows the absence of collinearity issues, the dependent variables are not intercorrelated.

4.6. Hypothesis Testing

The hypothesis testing results presented in

Table 9 indicate that TL does not have a statistically significant effect on TP. TL has an original sample coefficient of 0.034, a sample mean of 0.038, and a standard deviation of 0.066. The corresponding

p-value of 0.611 (>0.05) suggests that TL does not significantly predict TP. Conversely, WE exhibits a significant positive relationship with TP, with an original sample coefficient of 0.491, a sample mean of 0.491, and a standard deviation of 0.067. The strong t-statistic of 7.359 and a

p-value of less than 0.001 indicate that an increase in WE will lead to an increase in TP.

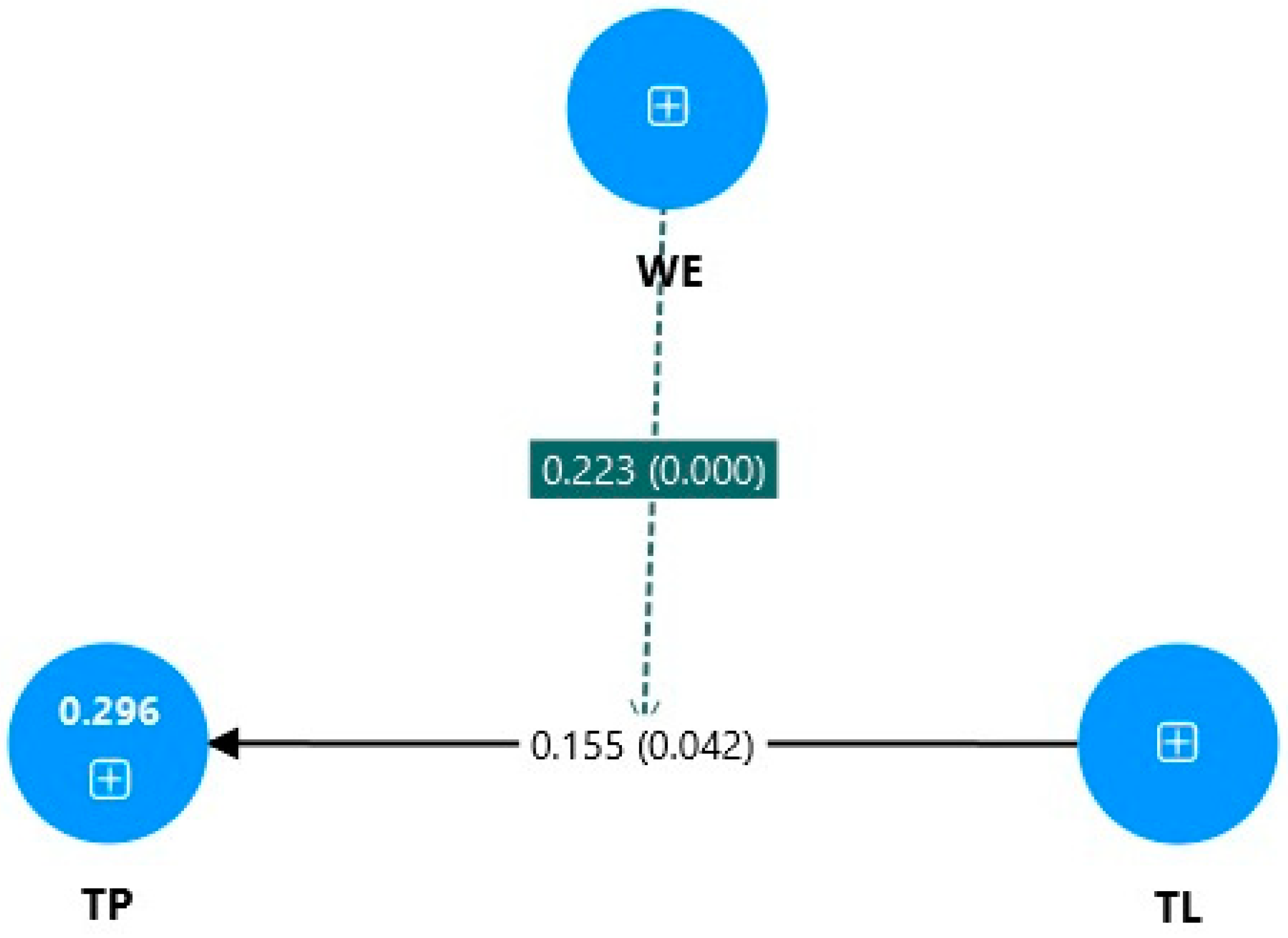

Figure 3 illustrates the moderating effect of WE on the TL–TP relationship. The results indicate that WE moderates the impact of TL on TP, with a moderation coefficient of 0.223 (

p = 0.000). This confirms that while TL alone does not significantly impact TP, its effect becomes more pronounced in a positive work environment.

To further examine this effect,

Figure 4 presents a simple slope analysis demonstrating how TL’s impact on TP varies at different levels of WE. The simple slope analysis in

Figure 4 illustrates how the impact of TL on TP varies at different levels of WE. The green line (WE at +1 SD) indicates that transformational leadership has a strong and statistically significant positive effect on teacher performance in highly supportive work environments. The blue line (WE at the mean) reflects a weaker but still positive association. In contrast, the red line (WE at −1 SD) demonstrates a negligible or slightly negative relationship, suggesting that in unsupportive environments, transformational leadership fails to enhance teacher performance. These patterns confirm that the strength and direction of the TL–TP relationship are contingent on the level of workplace support, reinforcing the importance of contextual enablers for effective leadership.

The findings suggest that while transformational leadership alone does not significantly impact teacher performance, its effect is moderated by the work environment. A supportive work environment amplifies the positive influence of TL on TP, while a negative work environment weakens or even negates this relationship. Additionally, the work environment directly improves teacher performance, highlighting its critical role in shaping teacher effectiveness amid ongoing turmoil in Lebanese schools.

5. Discussion

The research investigates the influence of transformational leadership and the work environment on teachers’ performance in crisis-affected educational settings in Lebanon, in addition to the moderating role of the work environment. The results reveal important insights into the relationships between these variables within this challenging context.

The analysis indicates that transformational leadership has a sample coefficient of 0.034, with a corresponding p-value of 0.611 (>0.05). This suggests that transformational leadership does not have a statistically significant effect on predicting teacher performance, meaning that H1 was not supported. This finding contrasts with previous studies conducted in more stable educational settings, where transformational leadership has been widely recognized as a positive driver of teacher performance. This weak and statistically non-significant link between transformational leadership and teacher performance may reflect several context-specific realities. First, it could indicate leadership fatigue, whereby school leaders themselves, affected by the chronic crisis, are unable to consistently demonstrate the idealized and inspirational behaviors typically associated with transformational leadership. Second, the result may point to a misalignment between what transformational leadership offers (e.g., vision, motivation, intellectual stimulation) and what teachers currently need—namely, stability, resources, and emotional support. In this light, the motivational appeals of transformational leaders may fall flat in an environment where professional burnout, job insecurity, and survival concerns dominate. Finally, the finding could suggest a degree of contextual irrelevance; transformational leadership, often effective in stable and resourced settings, may not be directly transferable to fragile-state educational systems without adaptation. This reinforces the need for hybrid or adaptive leadership approaches that respond to the lived realities of educators during crises.

In contrast, the work environment demonstrates a strong and significant positive relationship with teacher performance, evidenced by a sample coefficient of 0.491 and a p-value of less than 0.001, meaning that H

2 is accepted. These findings indicate that an improvement in the work environment is likely to lead to enhanced teacher performance, highlighting its critical role in this context. Several previous studies, such as

Vitria et al. (

2021),

Kant and Asefa (

2022),

Asad et al. (

2022),

Andriani et al. (

2018),

Sudibjo and Nasution (

2020), and

Sirait (

2021) have underscored the importance of a positive work environment in fostering teacher motivation, professional growth, and overall performance. Thus, a supportive work environment may provide stability, adequate resources, and emotional reassurance, which are particularly critical in crisis-affected educational settings. When teachers feel supported, they are more likely to stay engaged, maintain morale, and deliver quality instruction despite external challenges.

Moreover, the moderating role of the work environment on the relationship between transformational leadership and teacher performance provides additional insight. The simple slope analysis illustrates that when the work environment is highly supportive (+1 SD), transformational leadership has a stronger positive impact on teacher performance. However, when the work environment is poor (−1 SD), transformational leadership’s effect is weakened or even becomes negligible. This supports H3, indicating that the effectiveness of transformational leadership in improving teacher performance depends on the quality of the work environment.

These findings align with contingency leadership theories (

Atasoy, 2020;

Villoria, 2023), which propose that leadership effectiveness is context-dependent. In crisis-affected schools, where stress, instability, and resource constraints dominate, transformational leadership alone may not be sufficient to drive performance improvements. Instead, a strong and supportive work environment acts as a prerequisite that allows transformational leadership to have a meaningful impact. When teachers feel supported through job security, access to resources, and an emotionally stable environment, they may be more receptive to transformational leadership’s motivational aspects. Conversely, in a poor work environment, even highly inspirational leadership may fail to engage teachers, as their primary focus remains on survival and coping with external pressures.

Additionally, elements of individualized consideration, a key component of transformational leadership, may be particularly relevant in crisis conditions. Teachers experiencing heightened stress and burnout may respond more positively to personalized support and encouragement from leaders. This suggests that rather than relying solely on broad transformational leadership strategies, leaders in crisis-affected schools should prioritize creating a stable, supportive, and resource-rich environment to enable transformational leadership to take effect.

Finally, these findings align with Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, which suggests that individuals must satisfy basic physiological and safety needs before they can fully respond to higher-order motivations such as self-actualization or professional growth. In Lebanon’s current crisis environment, teachers are likely operating at the lower tiers of the hierarchy, where concerns over salary, job security, and emotional stability take precedence. As such, the motivational appeals of transformational leadership focused on vision, purpose, and inspiration, may have limited effectiveness when fundamental psychological needs remain unmet. This reinforces the importance of creating a work environment that provides not only material support but also psychological safety and emotional reassurance.

6. Implications

6.1. Practical Implications

Given Lebanon’s ongoing economic and political crises and the financial constraints that limit costly interventions, several practical recommendations emerge from this study’s findings.

First, educational managers and policymakers should prioritize low-cost strategies to enhance the work environment. These can include fostering a culture of collaboration, promoting transparent and open communication, and optimizing existing resources to provide professional and emotional support for teachers. Creating a positive and stable work environment can significantly enhance teacher performance without requiring substantial financial investments. These recommendations align with international frameworks that emphasize the need for psychosocial support, collegial collaboration, and resource-efficient strategies to sustain teacher effectiveness in crisis-affected contexts (

INEE, 2010;

Kirk & Winthrop, 2006).

Second, while transformational leadership remains valuable, its effectiveness is contingent on addressing teachers’ immediate concerns. School leaders should strive to inspire and motivate teachers while simultaneously offering practical support, such as facilitating access to teaching materials, reducing administrative burdens, and providing emotional reassurance. By balancing visionary leadership with responsive management, educational leaders can create conditions that allow transformational leadership to thrive.

Third, professional development programs for educational leaders should focus on adaptive leadership strategies tailored to Lebanon’s socioeconomic and political realities. Training should equip school administrators with the skills to respond flexibly to crises, manage teacher well-being, and foster resilience in uncertain conditions. Leadership development programs should emphasize not only transformational leadership techniques but also practical crisis management skills.

Fourth, schools should leverage existing resources to regularly assess teachers’ needs and challenges without requiring substantial financial investments. Simple, structured feedback mechanisms such as anonymous surveys, focus group discussions, and teacher consultations can provide valuable insights for leadership and resource allocation decisions. Addressing teachers’ most pressing concerns through targeted interventions can lead to improved morale and performance.

Finally, to maximize the impact of transformational leadership, school leaders must actively cultivate an environment that enables it to flourish. Encouraging teacher collaboration through structured peer-support networks, integrating teachers into decision-making processes, and implementing shared problem-solving approaches can enhance engagement and resilience. By fostering a work culture that aligns with transformational leadership principles, schools can help teachers navigate crises more effectively and sustain high levels of performance.

6.2. Policy Implications

Lebanon’s ongoing economic and political instability necessitates educational policies that are pragmatic, resource-efficient, and responsive to teachers’ immediate needs. The findings emphasize that creating a supportive work environment is critical for sustaining teacher performance in crisis conditions. Policymakers should focus on promoting school stability, enhancing resourcefulness, and reinforcing informal support structures to compensate for financial constraints.

First, in the absence of substantial financial resources, schools should strengthen informal support systems such as peer mentoring and collaborative teaching practices. Encouraging experienced teachers to mentor newer staff, implementing shared lesson planning, and adopting flexible work arrangements can help alleviate stress and improve teacher effectiveness. These low-cost interventions can foster a sense of community and resilience within schools. These low-cost interventions can foster a sense of community and resilience within schools. These approaches are supported by evidence that community-based and peer-driven strategies are effective in maintaining teacher engagement in low-resource environments (

UNESCO, 2021;

INEE, 2010).

Second, engaging parents and the broader community can provide additional support for both teachers and students. Community-driven initiatives, such as volunteer programs, local sponsorships, and parental involvement in school activities, can help create a more supportive work environment without requiring significant financial investments. Schools should leverage these partnerships to improve teacher morale and provide additional classroom resources.

Finally, policies should focus on promoting school stability and efficient resource management. Ensuring job security for teachers can minimize turnover and burnout while streamlining administrative procedures can allow teachers to focus more on instruction. Additionally, encouraging resource-sharing partnerships between schools, NGOs, and private-sector organizations can help optimize available materials and infrastructure. By reinforcing teacher support structures, facilitating collaboration, and leveraging community resources, policymakers can help sustain teacher performance and educational quality even in crisis conditions.

6.3. Limitations of the Study and Implications for Future Research

Although this study contributes to the literature by offering critical insights into how prolonged socio-economic crises can alter the dynamics of leadership effectiveness within educational institutions and adds value by addressing a gap in the existing research regarding teacher performance in crisis-stricken regions, it has several limitations. Firstly, the research used a mono-method quantitative approach, relying solely on surveys for data collection. This approach may overlook qualitative methods and contextual intricacies, which could provide a deeper understanding of the phenomena under investigation. Future studies could employ mixed-method approaches to complement quantitative findings with qualitative insights. Secondly, a cross-sectional design was chosen due to time and resource constraints, allowing for a broad snapshot of leadership and work environment effects within Lebanese schools. While longitudinal studies could provide stronger causal evidence, this study serves as an initial step in understanding these relationships under crisis conditions. Third, although our sample included both public and private school teachers, a subgroup analysis to explore whether the effects of transformational leadership and work environment differed across school types was not conducted. Given the structural, financial, and managerial differences between public and private institutions in Lebanon, such an analysis could reveal important variations in how leadership strategies and workplace conditions impact teacher performance. It is recommended that future research examine these subgroup dynamics to develop more tailored and context-sensitive recommendations for each educational sector. Lastly, the research was conducted in Lebanese schools amid turmoil, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other cultural or educational contexts. Future studies could explore how different leadership styles operate within the context of economic and political crises. Understanding these dynamics can help identify effective strategies for enhancing teacher performance in similarly challenging environments. Future research could also compare the findings from this study with those in other crisis-affected regions to draw broader conclusions about the interplay of leadership and work environment on teacher performance.

In conclusion, this study offers significant contributions to the understanding of teacher performance within the context of crisis-affected educational settings in Lebanon. This research emphasizes that a supportive work environment is essential for enhancing educational outcomes during times of instability. This insight is particularly critical given the ongoing economic and political challenges faced by Lebanese schools, where conventional leadership strategies may be insufficient without addressing foundational workplace conditions. Ultimately, this study not only augments the existing literature on educational leadership but also provides practical implications for policymakers and school administrators. By fostering a supportive work environment, stakeholders can create conditions that empower teachers and ultimately improve student learning outcomes, thereby contributing to the resilience and sustainability of the educational sector in Lebanon and other crisis-affected countries.