Optimism, General Self-Efficacy, and Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy Among Greek Students: Research, Management, and Society

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Literature Review

2.1. Self-Efficacy, Social Cognitive Career Theory, and Entrepreneurship

2.2. Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy

2.3. General Self-Efficacy

2.4. Positive Emotions: Optimism

3. Methodology

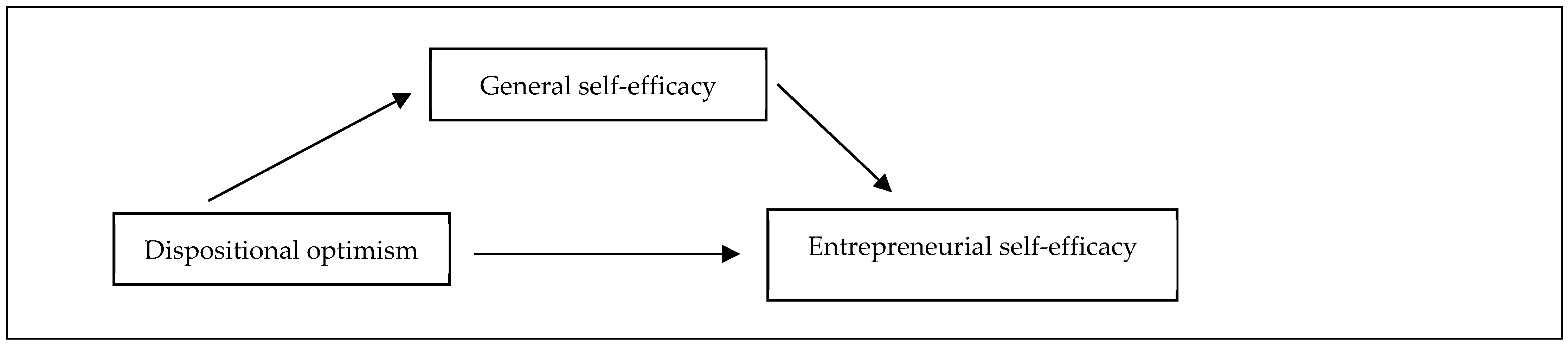

3.1. Purpose of the Study

- (a)

- Is there a significant relationship between optimism (predictor/independent variable) and the level of entrepreneurial self-efficacy? (outcome/dependent variable)

- (b)

- Is there a significant relationship between optimism (predictor/independent variable) and general self-efficacy? (mediator variable)

- (c)

- Is there a significant relationship between general self-efficacy (mediator variable) and the level of entrepreneurial self-efficacy (outcome/dependent variable) with the predictor controlled?

- (d)

- Is the strength of the relationship between optimism (predictor/independent variable) and entrepreneurial self-efficacy (outcome/dependent variable) significantly reduced when general self-efficacy (mediator) is added to the model?

- (e)

- Is the parameter coefficient (standardized beta) weight reducedwhen both the independent variable/predictor (optimism) and themediator (general self-efficacy) are related to the outcome variable (entrepreneurial self-efficacy) rather than standardized beta, indicating the relation between the independent variable/predictor (optimism) and outcome/dependent variable (entrepreneurial self-efficacy)?

3.2. Sample and Procedure

3.3. Measures

3.4. Statistical Methodology

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions, Practical Implications, Future Research

7. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. (2002). Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 32(4), 665–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, T. J., Qian, S., Miao, C., & Fiet, J. O. (2014). The relationship between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intentions: A meta-analytic review. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 38, 12095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1982). Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. The American Psychologist, 37(2), 122–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1986). The explanatory and predictive scope of self-efficacy theory. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 4(3), 359–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1989). Human agency in social-cognitive theory. American Psychologist, 44, 1175–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1991). Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50, 248–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Freeman and Co. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. (2012). On the functional properties of perceived self-efficacy revisited. Journal of Management, 38, 9–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, S. D., Gerhardt, M. W., & Kickul, J. R. (2007). The role of cognitive style and risk preference on entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies, 13, 86–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, J. R., & Locke, E. A. (2004). The relationship of entrepreneurial traits, skill, and motivation to new venture growth. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89, 587–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betz, N. E. (2008). Advances in vocational theories. In S. D. Brown, & R. W. Lent (Eds.), Handbook of counselling psychology (4th ed., pp. 357–374). Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Bird, B., & Schjoedt, L. (2009). Entrepreneurial behavior: Its nature, scope, recent research, and agenda for future research. In A. Carsrud, & M. Brännback (Eds.), Understanding the entrepreneurial mind: Opening the black box (pp. 327–358). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, N. G., & Vozikis, G. S. (1994). The influence of self-efficacy on the development of entrepreneurial intentions and actions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 18, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T. A. (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research (2nd ed.). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, J. C., & Sequeira, J. M. (2007). Prior family business exposure as intergenerational influence and entrepreneurial intent: A theory of planned behavior approach. Journal of Business Research, 60, 1090–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, N. M., & Brush, C. G. (2004). Gender. In W. B. Gartner, K. G. Shaver, N. M. Carter, & P. D. Reynolds (Eds.), Handbook of entrerpreneurial dynamics (pp. 12–25). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Charokopaki, A., & Argyropoulou, A. (2019). Optimism, career decision self-efficacy, and career indecision among Greek adolescents. Education Quarterly Reviews, 2(1), 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charokopaki, A., Kaliris, A., & Argyropoulou, K. (2019). Resilience and career decision-making self-efficacy among Greek NEETs: Implications for career counseling. Proceedings of the International Association for Educational and Vocational Guidance. Available online: https://iaevgconference2019.sk/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/IAEVG-Conference-Proceedings-2019_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Charokopaki, A., Krokidi, M., & Thoulis, T. (in press). Resilience, optimism and career adaptability in higher education students. Psychology: The Psychology: The Journal of the Hellenic Psychological Society. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G., Gully, S. M., & Eden, D. (2001). Validation of a new general self-efficacy scale. Organizational Research Methods, 4(1), 62–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G., Gully, S. M., & Eden, D. (2004). General self-efficacy and self-esteem: Toward theoretical and empirical distinction between correlated self-evaluations. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25, 375–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, D. A., Ciesla, J. R., & Steiger, J. H. (2007). The insidious effects of item wording: Method bias in the Children’s Depression Inventory. Psychological Methods, 12(4), 381–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delanoë-Gueguen, S., & Liñán, F. (2018). A longitudinal analysis of the influence of career motivations on entrepreneurial intention and action. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences/Revue Canadienne des Sciences de l’Administration, 36(4), 527–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiFabio, A., & Kenny, M. (2011). Promoting emotional intelligence and career decision-making among Italian high school students. Journal of Career Assessment, 19(1), 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douros, P., & Kaldis, P. (2024). Cultural heritage and contemporary creative management and sustainable economic development. Kallipos, Open Academic Editions. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, D. (2005). The effects of strategic decision making on entrepreneurial self-efficacy. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29, 599–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B. L., Mancuso, R. A., Branigan, C., & Tugade, M. M. (2000). The undoing effect of positive emotions. Motivation and Emotion, 24(4), 237–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B. L., Tugade, M. M., Waugh, C. E., & Larkin, G. R. (2004). What good are positive emotions in crises? A prospective study of resilience and emotions following the terrorist attacks on the United States on September 11th, 2001. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganguly, R., & Perera, H. N. (2018). Profiles of psychological resilience in college students with disabilities. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 37(5), 635–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gielnik, M. M., Frese, M., Kahara-Kawuki, A., WasswaKatono, I., Kyejjusa, S., Ngoma, M., Munene, J., Namatovu-Dawa, R., Nansubuga, F., Orobia, L., Oyugi, J., Sejjaaka, S., Sserwanga, A., Walter, T., Bischoff, K. M., & Dlugosch, T. J. (2015). Action and action-regulation in entrepreneurship: Evaluating a student training for promoting entrepreneurship. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 14(1), 69–94. [Google Scholar]

- Gunkel, M., Scroggins, W. A., Schlaegel, C., Langella, I. M., & Peluchette, J. V. (2010). Personality and career decisiveness: An international empirical comparison of business students’ career planning. Personnel Review, 39(4), 503–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hmieleski, K. M., & Baron, R. A. (2009). Entrepreneurs’ optimism and new venture performance: A social cognitive perspective. Academy of Management Journal, 52, 473–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hmieleski, K. M., & Corbett, A. C. (2008). The contrasting interaction effects of improvisational behavior with entrepreneurial self-efficacy on new venture performance and entrepreneur work satisfaction. Journal of Business Venturing, 23, 482–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, D. K., Burmeister-Lamp, K., Simmons, S. A., Foo, M.-D., Hong, M. C., & Pipes, J. D. (2019). I know I can, but I don’t fit: Perceived fit, self-efficacy, and entrepreneurial intention. Journal of Business Venturing, 34(2), 311–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T. A., Erez, A., & Bono, J. A. (1998). The power of being positive: The relationship between positive self-concept and job performance. Human Performance, 11, 167–187. [Google Scholar]

- Kakouris, A., Tampouri, S., Kaliris, A., Mastrokoukou, S., & Georgopoulos, N. (2023). Entrepreneurship as a career option within education: A critical review of psychological constructs. Education Sciences, 14(1), 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaliris, A., Sidiropoulou-Dimakakou, D., Argyropoulou, A., & Fakiolas, N. (2013). Self-efficacy beliefs and counseling competencies of career counselors providing services in big nterprises and counseling companies. Psychology, 20(2), 230–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaliris, A., Sidiropoulou-Dimakakou, D., Drosos, N., Argiropoulou, K., & Foundouka, A. (2017, May 15). Positive psychological factors in career decision-making in adolescents: Survey results & recommendations for counseling practice. 16th Panhellenic Congress of Psychological Research, Thessaloniki, Greece. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R. B. (2016). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (4th ed.). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kritikos, A. S. (2024). Entrepreneurs and their impact on jobs and economic growth. IZA World of Labor, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuratko, D., Morris, M., & Schindehutte, M. (2015). Understanding the dynamics of entrepreneurship through framework approaches. Small Business Economics, 45, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lareno, A., Vazquez, J. L., & Aza, C. (2016). Social cognitive determinants of entrepreneurial career choice in university students. International Small Business Journal, 34(8), 1053–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. H., & Wong, P. K. (2004). An exploratory study of technopreneurial intentions: A career anchor perspective. Journal of Business Venturing, 19(1), 7–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lent, R. W., & Brown, S. D. (2013). Social cognitive model of career self-management: Toward a unifying view of adaptive career behavior across the life span. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 60(4), 557–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lent, R. W., Brown, S. D., & Hackett, G. (1994). Toward a unifying social cognitive theory of career and academic interest, choice, and performance (Monograph). Journal of Vocational Behavior, 45, 79–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lent, R. W., Brown, S. D., & Hackett, G. (2002). Social cognitive career theory. In D. Brown, & Associates (Eds.), Career choice and development (4th ed., pp. 255–311). Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Lent, R. W., Sheu, H., Singley, D., Schmidt, J., Schmidt, L. C., & Gloster, C. S. (2008). Longitudinal relations of self-efficacy to outcome expectations, interests, and major choice goals in engineering students. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 73, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liguori, E. W., Bendickson, J. S., & McDowell, W. C. (2018). Revisiting entrepreneurial intentions: A social cognitive career theory approach. International Entrepreneurial Management Journal, 14, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liguori, E. W., Winkler, C., Vanevenhoven, J., Winkel, D., & James, M. (2019). Entrepreneurship as a career choice: Intentions, attitudes, and outcome expectations. InternationalJournal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship, 32(4), 311–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, F., & Fayolle, A. (2015). A systematic literature review on entrepreneurial intentions: Citation, thematic analyses, and research agenda. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 11(4), 907–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malikiosi-Loizos, M. (2020). Positive psychology in Greece: Latest developments. Psychology: The Journal of the Hellenic Psychological Society, 25(1), 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markman, G. D., Balkin, D. B., & Baron, R. A. (2002). Inventors and new venture formation: The effects of general self-efficacy and regretful thinking. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 27(2), 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauer, R., Eckerle, P., & Brettel, M. (2013). Adding missing parts to the intention puzzle in entrepreneurship education: Entrepreneurship self-efficacy, its antecedents and their direct and mediated effect. In D. Smallbone, J. Leitao, M. Raposo, & F. Welter (Eds.), Frontiers in european entrepreneurship research (pp. 73–86). Edward Elgar. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, R. P. (1999). Test theory: A unified treatment (1st ed.). Psychology Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGee, J. E., Peterson, M., Mueller, S. L., & Sequeira, J. M. (2009). Refining the measure of entrepreneurial self-efficacy. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33, 965–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIlveen, P., Beccaria, G., & Burton, L. J. (2013). Beyond conscientiousness: Career optimism and satisfaction with academic major. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 83(3), 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mira-Solves, I., Estrada-Cruz, M., & Gomez-Gras, J. M. (2021). Analysing academics’ entrepreneurial opportunities: The influence of academic self-efficacy and networks. European Research on Management and Business Economics, 27(2), 100152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowiński, W., Haddoud, M. Y., Lančarič, D., Egerová, D., & Czeglédi, C. (2017). The impact of entrepreneurship education, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, and gender on entrepreneurial intentions of university students in the Visegrad countries. Studies in Higher Education, 44(2), 361–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A classification and handbook. Oxford University Press/American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-López, M. C., González-López, M. J., & Rodríguez-Ariza, L. (2019). Applying the social cognitive model of career self-management to the entrepreneurial career decision: The role of exploratory and coping adaptive behaviors. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 112, 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rauch, A., & Frese, M. (2007). Let’s put the person back into entrepreneurship research: A meta-analysis on the relationship between business owners’ personality traits, business creation, and success. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 16, 353–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosseel, Y. (2012). Iavaan: A R Package for Structural Equation Modelling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rottinghaus, P. J., Day, S. X., & Borgen, F. H. (2005). The Career Futures Inventory: A measure of career-related adaptability and optimism. Journal of Career Assessment, 13(1), 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, S. C., & Liguori, E. W. (2019a). Entrepreneurial self-efficacy and intentions: Outcome expectations as mediator and subjective norms as moderator. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 26(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, S. C., & Liguori, E. W. (2019b). How and when is self-efficacy related to entrepreneurial intentions: Exploiting the role of entrepreneurial outcome expectations and subjective norms. Revista de EstudiosEmpresariales. Segunda Epoca, (1), 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheier, M. F., & Carver, C. S. (1985). Optimism, coping, and health: Assessment and implications of generalized outcome expectancies. Health Psychology, 4(3), 219–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheier, M. F., Carver, C. S., & Bridges, M. W. (1994). Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): A reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(6), 1063–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, G., Borgia, D., & Schoenfeld, J. (2005). The motivation to become an entrepreneur. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 11(1), 42–57. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, J., Kim, J., & Mesquita, L. (2024). Does vicarious entrepreneurial failure induce or discourage one’s entrepreneurial intent? A mediated model of entrepreneurial self-efficacy and identity aspiration. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 1(30), 52–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahab, Y., Chengang, Y., Arbizu, A. D., & Haider, M. J. (2019). Entrepreneurial self-efficacy and intention: Do entrepreneurial creativity and education matter? International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 25(2), 259–280. [Google Scholar]

- Shapero, A., & Sokol, L. (1982). The social dimensions of entrepreneurship. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign’s Academy for Entrepreneurial Leadership Historical Research Reference in Entrepreneur-Ship. [Google Scholar]

- Sheu, H., & Bordon, J. (2017). SCCT research in the international context: Empirical evidence, future directions, and practical implications. Journal of Career Assessment, 25(1), 58–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, V. D., & Rojjanasrirat, W. (2011). Translation, adaptation and validation of instruments or scales for use in cross-cultural health care research: A clear and user-friendly guideline. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 17(2), 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovet, L., Annovazzi, C., Ginevra, M. C., Kaliris, A., & Lodi, E. (2018). Life design in adolescence: The role of positive psychological resources. In V. Cohen-Scali, L. Nota, & J. Rossier (Eds.), New perspectives on career guidance and counseling in Europe: Building careers in changing and diverse societies (pp. 23–37). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spagnoli, P., Santos, S. C., & Caetano, A. (2017). A contribution toward the adaptation and validation of the entrepreneurial self-efficacy scale in Italy and Portugal. Journal of Career Assessment, 25(4), 670–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spurk, D., Kauffeld, S., Barthauer, L., & Heinemann, N. S. R. (2015). Fostering networking behavior, career planning, and optimism, and subjective career success: An intervention study. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 87, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tampouri, S., Kakouris, A., Kaliris, A., & Kousiounelos, A. (2023, September 21–22). Introducing sources of self-efficacy and dysfunctional career beliefs in socio-cognitive career theory in entrepreneurship. 18th European Conference on Innovation and Entrepreneurship (Vol. 18, pp. 866–874), Online. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, K.-H., Chang, H.-C., & Peng, C.-Y. (2014). Extending the link between entrepreneurial self-efficacy and intention: A moderated mediation model. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 12(2), 445–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsechelidou, K. (2015). Poiotitazwis kai ergasia: Ta synaisthimataelpidas, aisiodoksias kai noimatoszwisstousepaggelmatikoussymvoulous [Quality of life and work: Emotions of hope, optimism, and meaning of life among career counselors] [Unpublished Master’s Thesis, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens]. [Google Scholar]

- Uysal, S. K., Karadag, H., Tuncer, B., & Sahin, F. (2022). Locus of control, need for achievement, and entrepreneurial intention: A moderated mediation model. The International Journal of Management Education, 20(2), 100560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanevenhoven, J., & Liguori, E. (2013). The impact of entrepreneurship education: Introducing the Entrepreneurship Education Project. Journal of Small Business Management, 51(3), 315–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardana, L. W., Narmaditya, B. S., Wibowo, A., Mahendra, A. M., Wibowo, N. A., Harwida, G., & Rohman, A. N. (2020). The impact of entrepreneurship education and students’ entrepreneurial mindset: The mediating role of attitude and self-efficacy. Heliyon, 6(9), e04922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, F., Kickul, J., & Marlino, D. (2007). Gender, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, and entrepreneurial career intentions: Implications for entrepreneurship education. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 31(3), 387–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulou, P., & Sahinidis, A. (2024). Students’ entrepreneurial intention and its influencing factors: A systematic literature review. Administrative Sciences, 14, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, K.-H., & Bentler, P. M. (2000). Three likelihood-based methods for mean and covariance structure analysis with nonnormal missing data. Sociological Methodology, 30, 165–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H., Seibert, C., & Hills, C. (2005). The mediating role of self-efficacy in the development of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(2), 1265–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

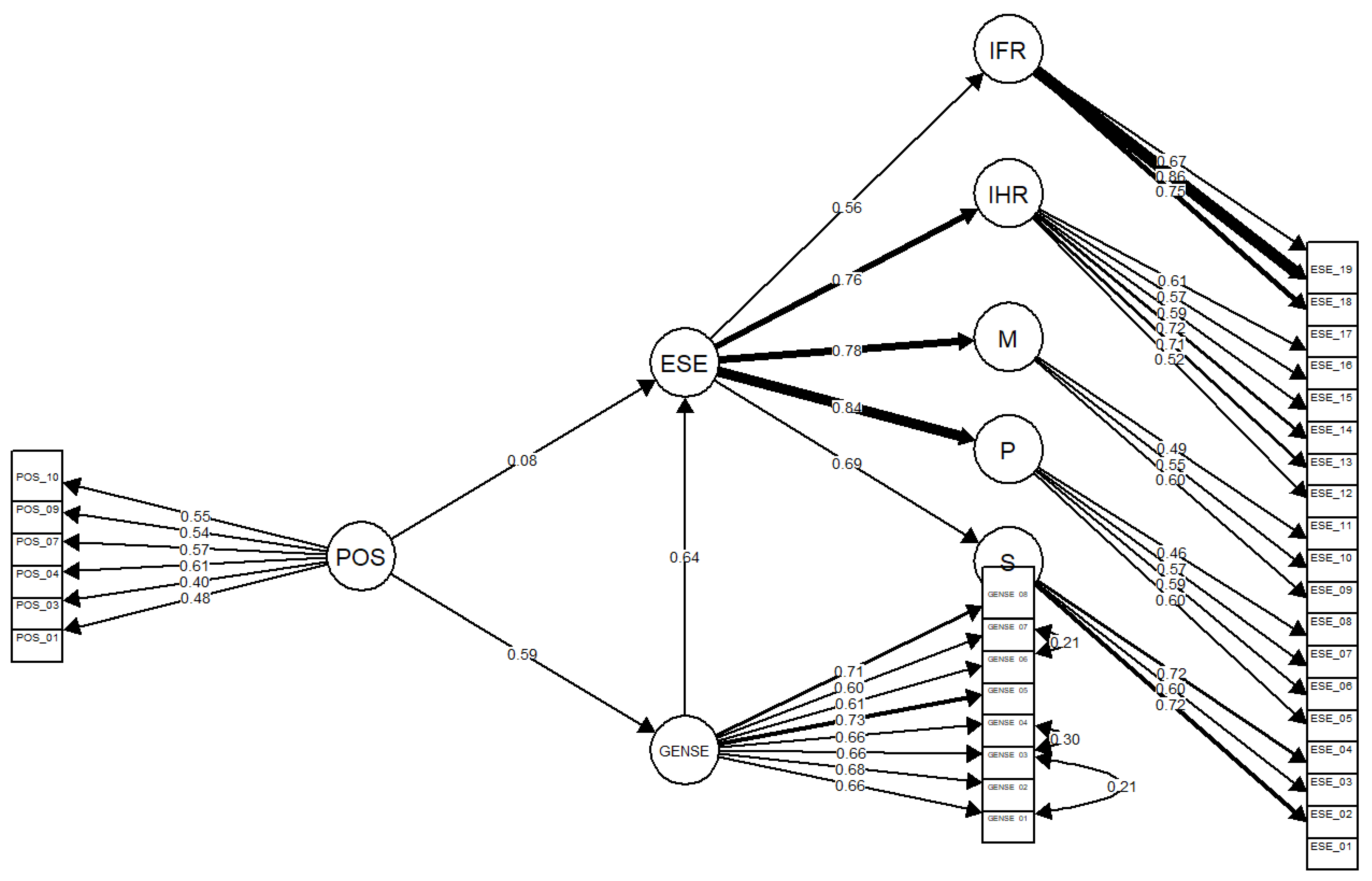

| Latent Variable | Indicator | Standardized Loading |

|---|---|---|

| GENSE | GENSE_01 | 0.662 |

| GENSE_02 | 0.684 | |

| GENSE_03 | 0.657 | |

| GENSE_04 | 0.664 | |

| GENSE_05 | 0.727 | |

| GENSE_06 | 0.608 | |

| GENSE_07 | 0.600 | |

| GENSE_08 | 0.709 | |

| POS | POS_01 | 0.476 |

| POS_03 | 0.404 | |

| POS_04 | 0.608 | |

| POS_07 | 0.573 | |

| POS_09 | 0.540 | |

| POS_10 | 0.549 | |

| S | ESE_01 | 0.725 |

| ESE_02 | 0.596 | |

| ESE_03 | 0.719 | |

| P | ESE_04 | 0.596 |

| ESE_05 | 0.588 | |

| ESE_06 | 0.567 | |

| ESE_07 | 0.462 | |

| M | ESE_08 | 0.605 |

| ESE_09 | 0.554 | |

| ESE_10 | 0.492 | |

| IHR | ESE_11 | 0.517 |

| ESE_12 | 0.714 | |

| ESE_13 | 0.717 | |

| ESE_14 | 0.592 | |

| ESE_15 | 0.574 | |

| ESE_16 | 0.614 | |

| IFR | ESE_17 | 0.754 |

| ESE_18 | 0.858 | |

| ESE_19 | 0.666 | |

| Second-order ESE | S | 0.693 |

| P | 0.844 | |

| M | 0.782 | |

| IHR | 0.756 | |

| IFR | 0.559 |

| Fit Index | Value |

|---|---|

| Comparative Fit Index (CFI) | 0.903 (robust) |

| Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) | 0.895 (robust) |

| RMSEA | 0.042 |

| 90% CI RMSEA | [0.038, 0.046] |

| SRMR | 0.054 |

| Construct | ω | AVE |

|---|---|---|

| GENSE | 0.841 | 0.440 |

| POS | 0.696 | 0.281 |

| S | 0.724 | 0.470 |

| P | 0.629 | 0.299 |

| M | 0.567 | 0.277 |

| IHR | 0.788 | 0.387 |

| IFR | 0.804 | 0.580 |

| Construct | GENSE | POS | S | P | M | IHR | IFR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) | |||||||

| GENSE | 0.594 | 0.226 | 0.315 | 0.384 | 0.356 | 0.344 | 0.254 |

| POS | 0.473 | 0.315 | 0.206 | 0.585 | 0.543 | 0.524 | 0.387 |

| S | 0.576 | 0.384 | 0.585 | 0.194 | 0.660 | 0.638 | 0.471 |

| P | 0.534 | 0.356 | 0.543 | 0.660 | 0.167 | 0.591 | 0.437 |

| M | 0.516 | 0.344 | 0.524 | 0.638 | 0.591 | 0.267 | 0.422 |

| IHR | 0.381 | 0.254 | 0.387 | 0.471 | 0.437 | 0.422 | 0.230 |

| IFR | 0.594 | 0.226 | 0.315 | 0.384 | 0.356 | 0.344 | 0.254 |

| (b) | |||||||

| GENSE | - | 0.585 | 0.465 | 0.498 | 0.585 | 0.520 | 0.401 |

| POS | 0.585 | - | 0.363 | 0.364 | 0.414 | 0.349 | 0.217 |

| S | 0.465 | 0.363 | - | 0.689 | 0.592 | 0.457 | 0.312 |

| P | 0.498 | 0.364 | 0.689 | - | 0.657 | 0.612 | 0.649 |

| M | 0.585 | 0.414 | 0.592 | 0.657 | - | 0.635 | 0.290 |

| IHR | 0.520 | 0.349 | 0.457 | 0.612 | 0.635 | - | 0.416 |

| IFR | 0.401 | 0.217 | 0.312 | 0.649 | 0.290 | 0.416 | - |

| Path | Estimate | SE | z-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| POS → GENSE (a) | 0.594 | 0.093 | 7.93 | <0.001 |

| GENSE → ESE (b) | 0.637 | 0.108 | 6.52 | <0.001 |

| POS → ESE (c) | 0.077 | 0.116 | 0.91 | 0.363 |

| Indirect (ab) | 0.378 | 0.094 | 5.51 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Charokopaki, A.; Douros, P. Optimism, General Self-Efficacy, and Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy Among Greek Students: Research, Management, and Society. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 242. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15070242

Charokopaki A, Douros P. Optimism, General Self-Efficacy, and Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy Among Greek Students: Research, Management, and Society. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(7):242. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15070242

Chicago/Turabian StyleCharokopaki, Argyro, and Panagiotis Douros. 2025. "Optimism, General Self-Efficacy, and Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy Among Greek Students: Research, Management, and Society" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 7: 242. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15070242

APA StyleCharokopaki, A., & Douros, P. (2025). Optimism, General Self-Efficacy, and Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy Among Greek Students: Research, Management, and Society. Administrative Sciences, 15(7), 242. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15070242