Exploring the Nexus Between a Supportive Workplace Environment, Employee Engagement, and Employee Performance in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

Abstract

1. Introduction

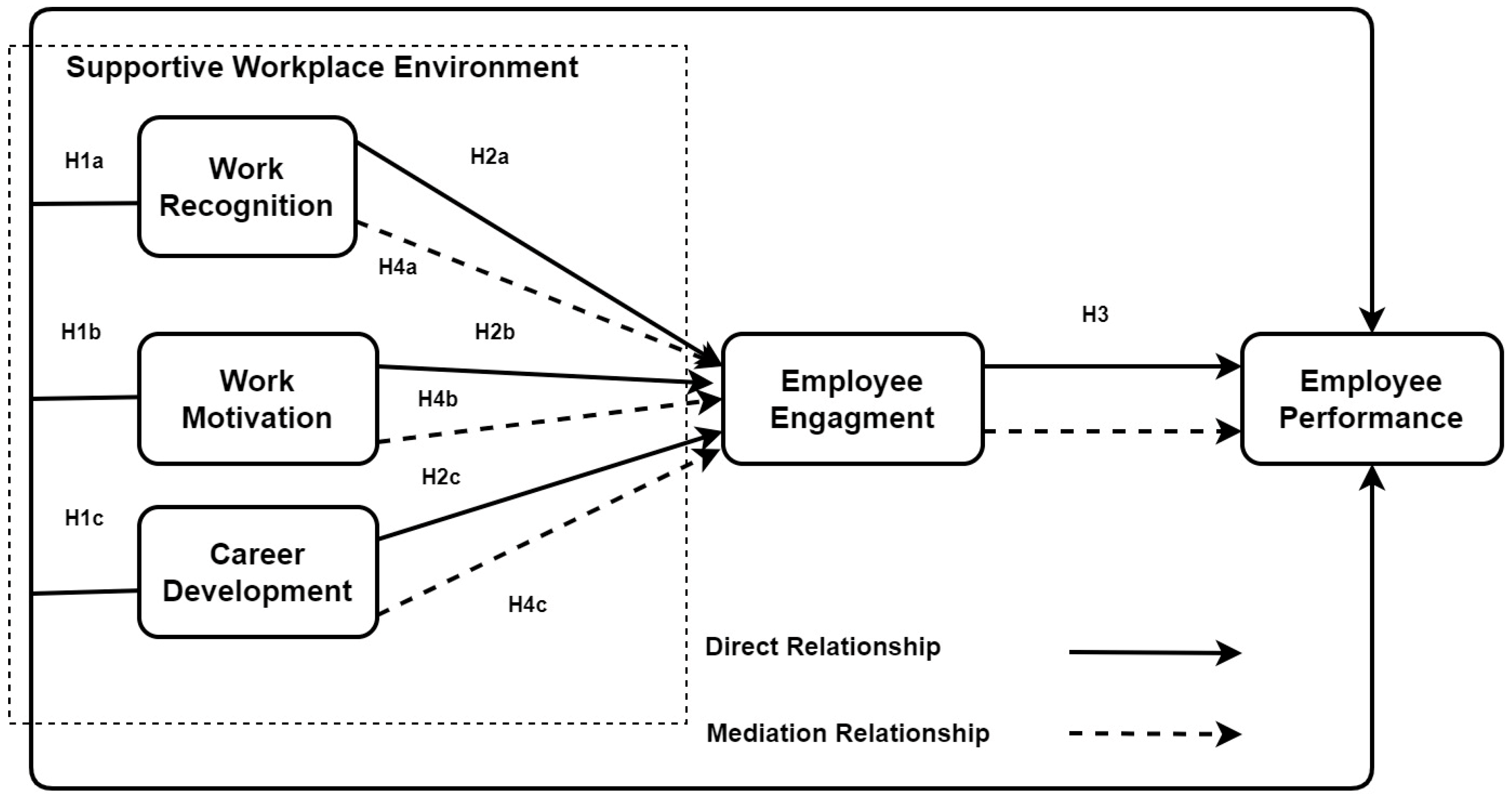

2. Hypothesis Development

2.1. Supportive Workplace Environment and Employee Performance

2.2. Work Recognition and Employee Engagement

2.3. Work Motivation and Employee Engagement

2.4. Career Development and Employee Engagement

2.5. Employee Engagement and Employee Performance

2.6. Mediating Effects of Employee Engagement

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Approach

3.2. Questionnaire Design

3.3. Ethical Considerations

3.4. Variables Measurements

3.4.1. Work Recognition

3.4.2. Work Motivation

3.4.3. Career Development

3.4.4. Employee Engagement

3.4.5. Employee Performance

3.5. Sampling and Data Collection

3.6. Demographics

4. Results

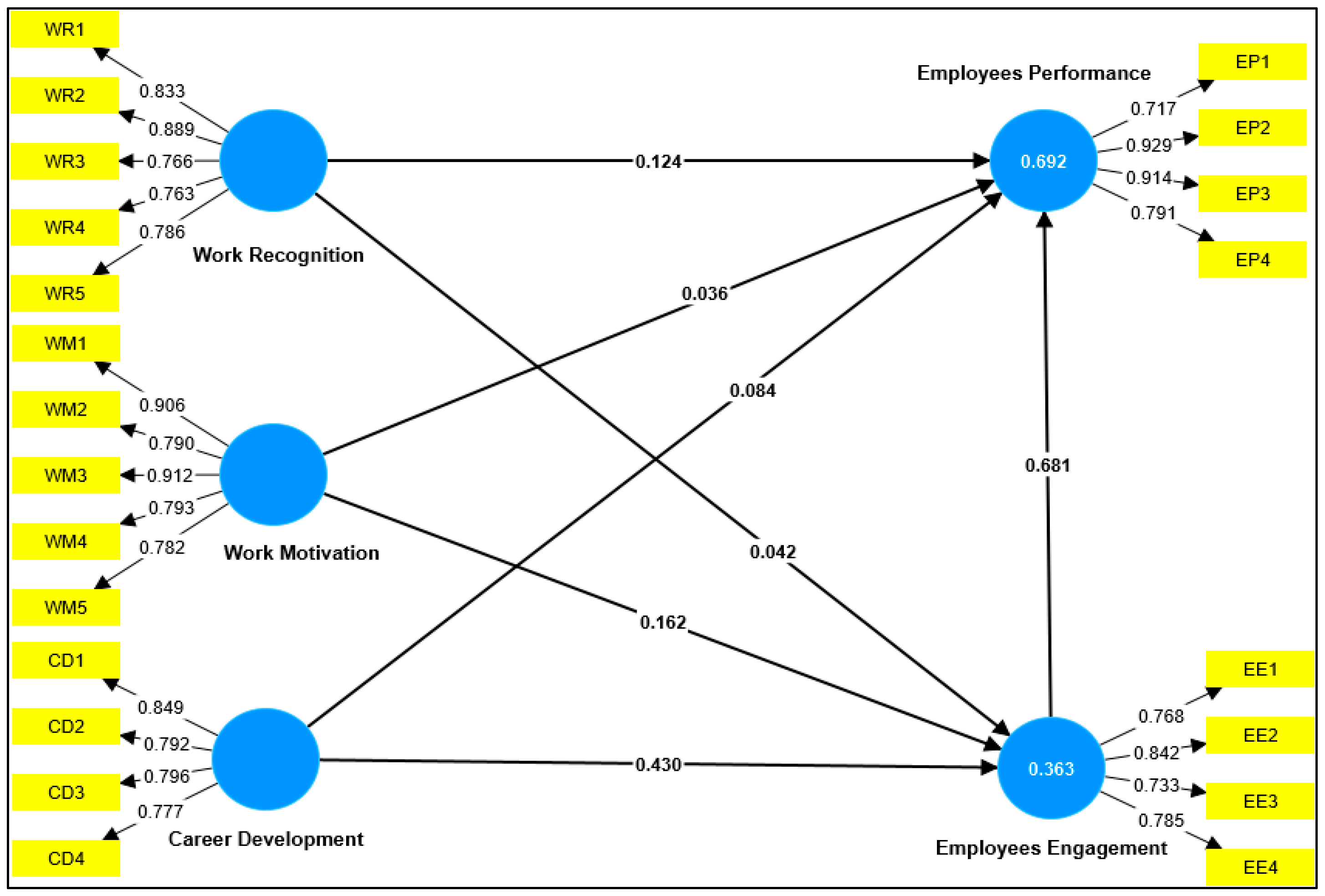

4.1. Measurement Model

4.2. Structural Model

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions and Implications

6.1. Conclusions

6.2. Implications

7. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Research Instrument | |

| Supportive Workplace Environment | |

| i. Work Recognition | |

| 1. | In my organization, I receive enough recognition for my work. |

| 2. | In my organization, I feel that I am valued. |

| 3. | I know about the recognition program provided in my organization. |

| 4. | Being recognized by your line manager is more important than being recognized by the general manager. |

| ii. Work Motivation | |

| 5. | I am satisfied with the traditional motivational initiatives offered by my organization such as bonuses and annual raises |

| 6. | The increase of work motivation initiatives in my organization affects my work performance positively. |

| 7. | In your opinion, money is the only motivation to do your work. |

| 8. | Assigning new types of tasks will motivate your work performance positively. |

| 9. | Being empowered by your manager to take decisions will motivate your work performance positively. |

| iii. Career Development | |

| 10. | Providing continuance work training will motivate your work performance positively. |

| 11. | Having a clear career path in your organization will motivate your work performance positively. |

| 12. | You think there are enough opportunities for promotions within your organization. |

| 13. | In your organization, being promoted after doing excellent work over the year will motivate you to work harder the next year. |

| Employee Engagement | |

| 14. | Your organization cares about its employees. |

| 15. | My opinions are sought on issues that affect me at my organization. |

| 16. | My manager helps me understand how my work is important to the organization. |

| 17. | There are opportunities for my own advancement in my organization. |

| Employee Performance | |

| 18. | I do only the work I am required to do as per my contract, no more no less. |

| 19. | Not being fired by your organization is the only reason you do your job perfectly. |

| 20. | Having a supportive manager will motivate your work performance positively. |

| 21. | Checking attendance and leaving hours will negatively affect my work performance negatively. |

References

- Abdullateef, S. T., Musa Alsheikh, R., & Khalifa Ibrahim Mohammed, B. (2023). Making Saudi vision 2030 a reality through educational transformation at the university level. Labour and Industry, 33(2), 231–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboelmaged, M. G. (2018). Knowledge sharing through enterprise social network (ESN) systems: Motivational drivers and their impact on employees’ productivity. Journal of Knowledge Management, 22(2), 362–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrutyn, S., & Lizardo, O. (2022). A motivational theory of roles, rewards, and institutions. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 53(2), 200–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achtenhagen, L., Haag, K., Hultén, K., & Lundgren, J. (2022). Torn between individual aspirations and the family legacy–individual career development in family firms. Career Development International, 27(2), 201–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahakwa, I., Yang, J., Tackie, E. A., & Atingabili, S. (2021). The influence of employee engagement, work environment and job satisfaction on organizational commitment and performance of employees: A sampling weights in PLS path modelling. SEISENSE Journal of Management, 4(3), 34–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamri, M. (2023). Transformational leadership and work engagement in public organizations: Promotion focus and public service motivation, how and when the effect occurs. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 44(1), 137–155. [Google Scholar]

- Albejaidi, F., & Nair, K. S. (2019). Building the health workforce: Saudi Arabia’s challenges in achieving Vision 2030. The International Journal of Health Planning and Management, 34(4), e1405–e1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albuainain, H. M., Alqurashi, M. M., Alsadery, H. A., Alghamdi, T. A., Alghamdi, A. A., Alghamdi, R. A., Albaqami, T. A., & Alghamdi, S. M. (2022). Workplace bullying in surgical environments in Saudi Arabia: A multiregional cross-sectional study. Journal of Family & Community Medicine, 29(2), 125. [Google Scholar]

- Aldabbas, H., Pinnington, A., & Lahrech, A. (2023). The influence of perceived organizational support on employee creativity: The mediating role of work engagement. Current Psychology, 42(8), 6501–6515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alenazy, A. A. K. (2022). Exploring antecedents and outcomes of corporate social responsibility in Saudi Arabia. La Trobe. [Google Scholar]

- Almulhim, A. I., & Al-Saidi, M. (2023). Circular economy and the resource nexus: Realignment and progress towards sustainable development in Saudi Arabia. Environmental Development, 46, 100851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlNemer, H. A., Hkiri, B., & Tissaoui, K. (2023). Dynamic impact of renewable and non-renewable energy consumption on CO2 emission and economic growth in Saudi Arabia: Fresh evidence from wavelet coherence analysis. Renewable Energy, 209, 340–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arwab, M., Adil, M., Nasir, M., & Ali, M. A. (2022). Task performance and training of employees: The mediating role of employee engagement in the tourism and hospitality industry. European Journal of Training and Development, 47(9), 900–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghar, M. Z., Barbera, E., Rasool, S. F., Seitamaa-Hakkarainen, P., & Mohelská, H. (2022). Adoption of social media-based knowledge-sharing behaviour and authentic leadership development: Evidence from the educational sector of Pakistan during COVID-19. Journal of Knowledge Management, 27(1), 59–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubouin-Bonnaventure, J., Chevalier, S., Lahiani, F.-J., & Fouquereau, E. (2023). Well-being and performance at work: A new approach favourable to the optimal functioning of workers through virtuous organisational practices. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 32(4), 608–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B. (2022). The social psychology of work engagement: State of the field. Career Development International, 27(1), 36–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2008). Towards a model of work engagement. Career Development International, 13(3), 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barhate, B., & Dirani, K. M. (2022). Career aspirations of generation Z: A systematic literature review. European Journal of Training and Development, 46(1/2), 139–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedarkar, M., & Pandita, D. (2014). A study on the drivers of employee engagement impacting employee performance. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 133, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, L., McDonald, P., & Cox, S. (2023). The critical role of co-worker involvement: An extended measure of the workplace environment to support work-life balance. Journal of Management & Organization, 29(2), 304–325. [Google Scholar]

- Brun, J.-P., & Dugas, N. (2008). An analysis of employee recognition: Perspectives on human resources practices. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 19(4), 716–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandani, A., Mehta, M., Mall, A., & Khokhar, V. (2016). Employee engagement: A review paper on factors affecting employee engagement. Indian Journal of Science and Technology, 9(15), 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry, N. I., Rasool, S. F., Raza, M., Mhelska, H., & Rehman, F. U. (2023). Exploring the linkage between workplace precaution measures, COVID-19 fear and job performance: The moderating effect of academic competence. Current Psychology, 42(23), 20239–20258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.-Y., Chang, P.-L., & Yeh, C.-W. (2004). An investigation of career development programs, job satisfaction, professional development and productivity: The case of Taiwan. Human Resource Development International, 7(4), 441–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chughtai, A. A., & Buckley, F. (2011). Work engagement: Antecedents, the mediating role of learning goal orientation and job performance. Career Development International, 16(7), 684–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S., Zhan, Y., Noe, R. A., & Jiang, K. (2022). Is it time to update and expand training motivation theory? A meta-analytic review of training motivation research in the 21st century. Journal of Applied Psychology, 107(7), 1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, N. (2005). Workplace learning environment and its relationship with learning outcomes in healthcare organizations. Human Resource Development International, 8(2), 185–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S. (1988). Psychosocial models of the role of social support in the etiology of physical disease. Health Psychology, 7(3), 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, F. L., Wang, J., & Bartram, T. (2019). Can a supportive workplace impact employee resilience in a high pressure performance environment? An investigation of the Chinese banking industry. Applied Psychology, 68(4), 695–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantidis, A. D., & Chatzoglou, P. (2019). Factors affecting employee performance: An empirical approach. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 68(1), 171–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y., Li, J., & Xu, Q. (2023). Are you satisfied when your job fits? The perspective of career management. Baltic Journal of Management, 18(5), 563–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furnham, A., MacRae, I., & Tetchner, J. (2021). Measuring work motivation: The facets of the work values questionnaire and work success. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 62(3), 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gegenfurtner, A., & Quesada-Pallarès, C. (2022). Toward a multidimensional conceptualization of motivation to transfer training: Validation of the transfer motivation questionnaire from a self-determination theory perspective using bifactor-ESEM. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 73, 101116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, D., Sekiguchi, T., & Fujimoto, Y. (2020). Psychological detachment: A creativity perspective on the link between intrinsic motivation and employee engagement. Personnel Review, 49(9), 1789–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X., & Frenkel, S. (2019). How perceptions of training impact employee performance: Evidence from two Chinese manufacturing firms. Personnel Review, 48(1), 163–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartnell, C. A., Christensen-Salem, A., Walumbwa, F. O., Stotler, D. J., Chiang, F. F., & Birtch, T. A. (2023). Manufacturing motivation in the mundane: Servant leadership’s influence on employees’ intrinsic motivation and performance. Journal of Business Ethics, 188(3), 533–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herr, E. L. (2001). Career development and its practice: A historical perspective. The Career Development Quarterly, 49(3), 196–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschi, A., Nagy, N., Baumeler, F., Johnston, C. S., & Spurk, D. (2018). Assessing key predictors of career success: Development and validation of the career resources questionnaire. Journal of Career Assessment, 26(2), 338–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.-C., Ahlstrom, D., Lee, A. Y.-P., Chen, S.-Y., & Hsieh, M.-J. (2016). High performance work systems, employee well-being, and job involvement: An empirical study. Personnel Review, 45(2), 296–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M., Rasool, S. F., Xuetong, W., Asghar, M. Z., & Alalshiekh, A. S. A. (2023). Investigating the nexus between critical success factors, supportive leadership, and entrepreneurial success: Evidence from the renewable energy projects. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 30(17), 49255–49269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, T., & Zhang, Y. (2023). The influences of cross-cultural adjustment and motivation on self-initiated expatriates’ innovative work behavior. Personnel Review, 52(4), 1255–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikhide, J. E., Timur, A. T., & Ogunmokun, O. A. (2023). A balanced perspective on the affordance of a gamified HRM system for employees’ creative performance. Personnel Review, 52(3), 631–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jena, L., & Nayak, U. (2023). Organizational career development and retention of millennial employees: The role of job engagement and organizational engagement. Asia-Pacific Journal of Business Administration. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaca-Atik, A., Meeuwisse, M., Gorgievski, M., & Smeets, G. (2023). Uncovering important 21st-century skills for sustainable career development of social sciences graduates: A systematic review. Educational Research Review, 39, 100528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, C., Patterson, M., & Dawson, J. (2017). Building work engagement: A systematic review and meta-analysis investigating the effectiveness of work engagement interventions. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 38(6), 792–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundi, Y. M., & Aboramadan, M. (2023). A multi-level examination of the link between diversity-related HR practices and employees’ performance: Evidence from Italy. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 32(2), 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwarteng, S., Frimpong, S. O., Asare, R., & Wiredu, T. J. N. (2023). Effect of employee recognition, employee engagement on their productivity: The role of transformational leadership style at Ghana Health Service. Current Psychology, 43(6), 5502–5013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- London, M. (1993). Relationships between career motivation, empowerment and support for career development. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 66(1), 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macias-Alonso, I., Kim, H., & González, A. L. (2023). Self-driven Women: Gendered mobility, employment, and the lift of the driving ban in Saudi Arabia. Gender, Place & Culture, 30(11), 1574–1593. [Google Scholar]

- Majid, M., Ramli, M. F., Badyalina, B., Roslan, A., & Hashim, A. J. (2020). Influence of engagement, work-environment, motivation, organizational learning, and supportive culture on job satisfaction. International Journal of Human Resource Studies, 10(4), 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, I., Macky, K., & Le Fevre, M. (2023). High-involvement work practices, employee trust and engagement: The mediating role of perceived organisational politics. Personnel Review, 52(4), 1321–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelson, C. (2005). Meaningful motivation for work motivation theory. Academy of Management Review, 30(2), 235–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monje Amor, A., & Calvo, N. (2023). Individual, job, and organizational dimensions of work engagement: Evidence from the tourism industry. Baltic Journal of Management, 18(1), 70–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napitupulu, S., Haryono, T., Laksmi Riani, A., Sawitri, H. S. R., & Harsono, M. (2017). The impact of career development on employee performance: An empirical study of the public sector in Indonesia. International Review of Public Administration, 22(3), 276–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nehra, N. S. (2023). Can employee engagement be attained through psychological detachment and job crafting: The mediating role of spirituality and intrinsic motivation. Journal of Organizational Effectiveness: People and Performance, 10(3), 368–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niati, D. R., Siregar, Z. M. E., & Prayoga, Y. (2021). The effect of training on work performance and career development: The role of motivation as intervening variable. Budapest International Research and Critics Institute (BIRCI-Journal): Humanities and Social Sciences, 4(2), 2385–2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obschonka, M., Pavez, I., Kautonen, T., Kibler, E., Salmela-Aro, K., & Wincent, J. (2023). Job burnout and work engagement in entrepreneurs: How the psychological utility of entrepreneurship drives healthy engagement. Journal of Business Venturing, 38(2), 106272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, S., & Hammoud, M. S. (2017). Effective employee engagement in the workplace. International Journal of Applied Management and Technology, 16(1), 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owoeye, I., Kiiru, D., & Muli, J. (2020). Recognition practices and employee performance: Understanding work engagement as a mediating pathway in kenyan context. Journal of Human Resource Management, 8(3), 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pincus, J. D. (2022). Employee Engagement as Human Motivation: Implications for Theory, Methods, and Practice. Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Science, 57(4), 1223–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirsoul, T., Parmentier, M., & Nils, F. (2023). One step beyond emotional intelligence measurement in the career development of adult learners: A bifactor exploratory structural equation modeling framework. Current Psychology, 42(7), 5834–5850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, I. A. (2023). Do existing theories still hold for the creative labor market? A model of creative workers’ engagement and creative performance from a management and organization perspective. In The creative class revisited: New analytical advances (pp. 41–81). World Scientific. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, M. (2017). Innovative tools and techniques to ensure effective employee engagement. Industrial and Commercial Training, 49(3), 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasool, S. F., Chin, T., Wang, M., Asghar, A., Khan, A., & Zhou, L. (2022). Exploring the role of organizational support, and critical success factors on renewable energy projects of Pakistan. Energy, 243, 122765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasool, S. F., Samma, M., Mohelska, H., & Rehman, F. U. (2023). Investigating the nexus between information technology capabilities, knowledge management, and green product innovation: Evidence from SME industry. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 30(19), 56174–56187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasool, S. F., Wang, M., Tang, M., Saeed, A., & Iqbal, J. (2021). How toxic workplace environment effects the employee engagement: The mediating role of organizational support and employee wellbeing. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(5), 2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raziq, A., & Maulabakhsh, R. (2015). Impact of working environment on job satisfaction. Procedia Economics and Finance, 23, 717–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, F. U., & Al-Ghazali, B. M. (2022). Evaluating the influence of social advertising, individual factors, and brand image on the buying behavior toward fashion clothing brands. Sage Open, 12(1), 21582440221088858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, F. U., & Prokop, V. (2023). Interplay in management practices, innovation, business environment, degree of competition and environmental policies: A comparative study. Business Process Management Journal, 29(3), 858–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, F. U., & Zeb, A. (2022). Translating the impacts of social advertising on Muslim consumers buying behavior: The moderating role of brand image. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 14(9), 2207–2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, F. U., & Zeb, A. (2023). Investigating the nexus between authentic leadership, employees’ green creativity, and psychological environment: Evidence from emerging economy. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 30(49), 107746–107758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reizer, A., Brender-Ilan, Y., & Sheaffer, Z. (2019). Employee motivation, emotions, and performance: A longitudinal diary study. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 34(6), 415–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C., Wende, S., & Becker, J. (2015). SmartPLS 3 [Computer software]. SmartPLS. Available online: http://www.smartpls.com (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Riyanto, S., Endri, E., & Herlisha, N. (2021). Effect of work motivation and job satisfaction on employee performance: Mediating role of employee engagement. Problems and Perspectives in Management, 19(3), 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruparel, N., Bhardwaj, S., Seth, H., & Choubisa, R. (2023). Systematic literature review of professional social media platforms: Development of a behavior adoption career development framework. Journal of Business Research, 156, 113482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saks, A. M., Gruman, J. A., & Zhang, Q. (2022). Organization engagement: A review and comparison to job engagement. Journal of Organizational Effectiveness: People and Performance, 9(1), 20–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salam, A. A. (2022). Saudi Arabia’s labor market transitions to thrive vision 2030: A demographic appraisal. In The palgrave handbook of global social problems (pp. 1–22). Springer. Available online: https://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1007/978-3-030-68127-2_315-1 (accessed on 7 September 2022).

- Sarwar, S. (2022). Impact of energy intensity, green economy and blue economy to achieve sustainable economic growth in GCC countries: Does Saudi Vision 2030 matters to GCC countries. Renewable Energy, 191, 30–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sein, Y. Y., & Dmytrenko, D. (2023). Translating the impact of internal and external factors in achieving the sustainable market competitiveness: The mediating role of management practices. Journal of Competitiveness, 15(1), 168. [Google Scholar]

- Shkoler, O., & Kimura, T. (2020). How does work motivation impact employees’ investment at work and their job engagement? A moderated-moderation perspective through an international lens. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 487698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuck, B., Twyford, D., Reio, T. G., Jr., & Shuck, A. (2014). Human resource development practices and employee engagement: Examining the connection with employee turnover intentions. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 25(2), 239–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, D., Chen, J. M., Sherman, J. W., & Calanchini, J. (2023). A recognition advantage for members of higher-status racial groups. British Journal of Psychology, 114, 188–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susanto, P. C., Syailendra, S., & Suryawan, R. F. (2023). Determination of motivation and performance: Analysis of job satisfaction, employee engagement and leadership. International Journal of Business and Applied Economics, 2(2), 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S. E. (2008). Fostering a supportive environment at work. The Psychologist-Manager Journal, 11(2), 265–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trépanier, S.-G., Peterson, C., Gagné, M., Fernet, C., Levesque-Côté, J., & Howard, J. L. (2023). Revisiting the multidimensional work motivation scale (MWMS). European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 32(2), 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, P., & Turner, P. (2020). What is employee engagement? Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Ugwu, F. O., Onyishi, I. E., & Rodríguez-Sánchez, A. M. (2014). Linking organizational trust with employee engagement: The role of psychological empowerment. Personnel Review, 43(3), 377–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkelhaus, S., Grosse, E. H., & Glock, C. H. (2022). Job satisfaction: An explorative study on work characteristics changes of employees in Intralogistics 4.0. Journal of Business Logistics, 43(3), 343–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q., & Donaldson, S. I. (2022). What are the differences between flow and work engagement? A systematic review of positive intervention research. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 18(3), 449–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousaf, S., Rasheed, M. I., Kaur, P., Islam, N., & Dhir, A. (2022). The dark side of phubbing in the workplace: Investigating the role of intrinsic motivation and the use of enterprise social media (ESM) in a cross-cultural setting. Journal of Business Research, 143, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographics | Classifications | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 276 | 79 |

| Female | 73 | 21 | |

| Total | 349 | 100.0 | |

| Education | Undergraduate | 154 | 44 |

| Master | 192 | 55 | |

| Doctorate | 3 | 1 | |

| Total | 349 | 100.0 | |

| Positions | Senior Managers | 84 | 24 |

| Middle Level Managers | 129 | 37 | |

| Supporting Staff | 136 | 39 | |

| Total | 349 | 100.0 | |

| Work Experience | Less than 5 years | 140 | 40 |

| 6–10 years | 112 | 32 | |

| Above 10 years | 97 | 28 | |

| Total | 349 | 100.0 |

| Construct | Items | Factor Loading | Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability (roh_a) | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Work Recognition | WR1 | 0.833 | 0.867 | 0.878 | 0.654 |

| WR2 | 0.889 | ||||

| WR3 | 0.766 | ||||

| WR4 | 0.763 | ||||

| WR5 | 0.786 | ||||

| Work Motivation | WM1 | 0.906 | 0.893 | 0.901 | 0.703 |

| WM2 | 0.790 | ||||

| WM3 | 0.912 | ||||

| WM4 | 0.793 | ||||

| WM5 | 0.782 | ||||

| Career Development | CD1 | 0.849 | 0.817 | 0.82 | 0.647 |

| CD2 | 0.792 | ||||

| CD3 | 0.796 | ||||

| CD4 | 0.777 | ||||

| Employees Engagement | EE1 | 0.768 | 0.792 | 0.826 | 0.613 |

| EE2 | 0.842 | ||||

| EE3 | 0.733 | ||||

| EE4 | 0.785 | ||||

| Employees Performance | EP1 | 0.717 | 0.861 | 0.888 | 0.710 |

| EP2 | 0.929 | ||||

| EP3 | 0.914 | ||||

| EP4 | 0.791 |

| Discriminant Validity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | CD | WM | WR | EE | EP |

| CD | 0.804 | ||||

| WM | 0.592 | 0.783 | |||

| WR | 0.561 | 0.511 | 0.842 | ||

| EE | 0.403 | 0.539 | 0.564 | 0.839 | |

| EP | 0.462 | 0.492 | 0.455 | 0.557 | 0.809 |

| HTMT | |||||

| CD | |||||

| WM | 0.421 | ||||

| WR | 0.328 | 0.532 | |||

| EE | 0.339 | 0.428 | 0.546 | ||

| EP | 0.303 | 0.371 | 0.439 | 0.452 | |

| Relationship | Estimate | Mean | SD | t-Value | R2 | F2 | VIF | Q2 | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD → EE | 0.430 | 0.431 | 0.082 | 5.241 | 0.363 | 0.035 | 2.055 | 0.348 | Supported |

| WM → EE | 0.162 | 0.161 | 0.087 | 2.862 | 0.021 | 1.615 | Supported | ||

| WR → EE | 0.042 | 0.045 | 0.082 | 2.513 | 0.042 | 1.708 | Supported | ||

| CD → EP | 0.084 | 0.084 | 0.065 | 1.996 | 0.692 | 0.032 | 1.707 | 0.384 | Supported |

| WM → EP | 0.036 | 0.034 | 0.062 | 1.972 | 0.261 | 1.577 | Supported | ||

| WR → EP | 0.124 | 0.124 | 0.048 | 2.594 | 0.243 | 1.599 | Supported | ||

| EE → EP | 0.681 | 0.683 | 0.034 | 19.993 | 0.521 | 1.482 | Supported |

| Relationship | Estimate | Mean | SD | t-Value | CILL | CIUL | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD → EE → EP | 0.293 | 0.294 | 0.058 | 5.023 | 0.184 | 0.411 | Supported |

| WM → EE → EP | 0.110 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 1.836 | 0.005 | 0.23 | Supported |

| WR → EE → EP | 0.029 | 0.03 | 0.056 | 1.713 | 0.082 | 0.142 | Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rasool, S.F.; Mohelska, H.; Rehman, F.U.; Raza, H.; Asghar, M.Z. Exploring the Nexus Between a Supportive Workplace Environment, Employee Engagement, and Employee Performance in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 230. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15060230

Rasool SF, Mohelska H, Rehman FU, Raza H, Asghar MZ. Exploring the Nexus Between a Supportive Workplace Environment, Employee Engagement, and Employee Performance in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(6):230. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15060230

Chicago/Turabian StyleRasool, Samma Faiz, Hana Mohelska, Fazal Ur Rehman, Hamid Raza, and Muhammad Zaheer Asghar. 2025. "Exploring the Nexus Between a Supportive Workplace Environment, Employee Engagement, and Employee Performance in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 6: 230. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15060230

APA StyleRasool, S. F., Mohelska, H., Rehman, F. U., Raza, H., & Asghar, M. Z. (2025). Exploring the Nexus Between a Supportive Workplace Environment, Employee Engagement, and Employee Performance in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Administrative Sciences, 15(6), 230. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15060230