2.1. The Specificity of Ecotourism Destinations

The International Ecotourism Society (TIES) defined ecotourism as “responsible travel to natural areas that conserves the environment, sustains the well-being of the local people, and involves interpretation and education” (

The International Ecotourism Society [TIES], 2015). Despite the abundance of academic focus on ecotourism, there is no universally accepted definition of ecotourism destinations, so this concept term can be interpreted in many different ways. For example,

Krider et al. (

2010) outlined that ecotourism destinations should (1) feature the natural environment as a central attraction, (2) offer the prospect of learning or education, and (3) at least intend to be sustainable environmentally, culturally, and economically. Considering the present study’s focus on the Romanian ecotourism context, the authors embraced the definition of ecotourism destinations provided by Romanian tourism authorities, which is in line with TIES’ vision.

The

Romanian Ministry of Economy, Entrepreneurship and Tourism (

2025) requires ecotourism destinations to promote responsible marketing, support sustainable businesses and local communities, raise environmental awareness, and enforce nature conservation. Based on existing international standards (Nature and Ecotourism Accreditation Program and Nature’s Best), the

Association of Ecotourism in Romania (

2025) proposes a set of principles for ecotourism development and planning: (1) focus on natural areas; (2) interpretation of the ecotourism product; (3) environmental sustainability; (4) ecotourism assists in the preservation of nature; (5) ecotourism adds constructive input in the development of local communities; (6) ecotourism raises the tourists’ degree of satisfaction; and (7) adequate marketing.

In the last decade, online marketing has become one of the main challenges of ecotourism development worldwide. The Internet and related technologies have transformed the way DMOs interact with their target audience and promote tourist destination brands (

Khan & Fatma, 2021). The use of official destinations’ social media accounts provides an interactive real-time experience between tourists and destination brands and may become a key element in the decision-making and planning phases. As ecotourism destinations hold several particularities compared to other types of tourism sites, their DMOs need to adapt the social media approach according to the characteristics and expectations of target visitors. Subsequently, there has been an increasing interest in researching how tourists use the internet to search for information related to ecotourism (

Sadiq & Adil, 2021;

Nogueira & Carvalho, 2024).

2.2. Conceptualizing Pre-Travel ODBE

The experience economy, coined by

Pine and Gilmore (

1998), emphasizes the idea of consumers valuing brands for their ability to create unique experiences.

Lindstrom (

2005) extended this idea to branding, advocating for a multisensory approach beyond traditional two-sense strategies, as brand experience design plays a crucial role in brand management.

S. Lee et al. (

2018) argued that sensory marketing shapes customer expectations by helping them visualize future experiences, making them more tangible. With the rise of online brands due to ICT advancements, traditional brands also expanded their digital presence. In this context,

Morgan-Thomas and Veloutsou (

2013) defined online brand experience as a holistic consumer response to website stimuli, highlighting the evolving nature of brand engagement in the digital landscape. The tourist experience unfolds in three stages: before, during, and after the trip. During the inspiration and planning stage, prospective travelers engage in “distant” experiences, often mediated by digital technology (

Sundbo & Dixit, 2020;

Sundbo & Hagedorn-Rasmussen, 2008). Official destination platforms (official websites, social media networks) managed by DMOs play a key role in this process (

S. Lee et al., 2018). These platforms aim to create engaging ODBEs that encourage future visits and enhance the destination’s competitiveness.

Points of contact between potential visitors and the destination during the pre-travel phase are very important for destination managers, as travelers’ mental and emotional perceptions of their expected on-site experience strongly influence their decision making (

Larsen, 2007;

Volo, 2010;

Tung & Ritchie, 2011). The internet serves as an effective tool for fulfilling not only functional travel needs but also hedonic, aesthetic, innovative, and social desires during the information-seeking process (

Gretzel & Fesenmaier, 2009;

Vogt & Fesenmaier, 1998). By facilitating positive pre-trip experiences, digital platforms enhance travel planning and anticipation (

Buhalis & Law, 2008;

Navío-Marco et al., 2018). In this phase, travelers are not only gathering information but also seeking inspiration and envisioning potential experiences (

Fesenmaier & Pearce, 2019;

Larsen, 2007;

Tung & Ritchie, 2011;

Volo, 2010).

Social media, as a space for sharing and interaction, has become a significant source of travel inspiration (

Fotis, 2015). As the online space is often the first point of contact between potential customers and tourism brands, studies on online tourism experiences have emerged (

Vlahovic-Mlakar & Ozretic-Dosen, 2022). Studies have highlighted the significant influence social media has on tourists’ destination choices (

Jiménez-Barreto et al., 2019;

Boley et al., 2018;

Molinillo et al., 2018). In particular, platforms like Facebook play a pivotal role in the pre-trip stage, offering critical information for travel planning and decision making (

Jadhav et al., 2018). Although ecotourism destinations have exceptional biodiversity and cultural heritage, little empirical research has examined how these destinations utilize Facebook to create online brand experiences that align with ecotourism values (

Dwivedi et al., 2021). This study addresses that gap by examining the role of social media, particularly Facebook, in creating favorable online destination brand experiences for Romanian ecotourism destinations.

While previous research has focused primarily on evaluating website features (

Sun et al., 2017;

Tang et al., 2012), fewer studies have examined the experiential aspects of destination online presence.

Choi et al. (

2016) explored how telepresence—defined as the sensation of “being there” in a virtual environment (

Steuer, 1992)—impacts users’ experiences on destination websites. Their findings suggest that engaging website features foster telepresence, which in turn influences both hedonic and utilitarian website performance (

Choi et al., 2016). Building on such insights, this paper centres on the virtual experience of ecotourism destinations on Facebook. Specifically, it examines how these online encounters influence prospective travellers in the anticipation phase of their journey. The necessity for DMOs to provide positive ODBE is growing along with the use of internet platforms for informational searches on tourist destinations. According to

Li et al. (

2017), consumers’ online interaction with official destination platforms (e.g., official websites, social media network: Facebook, Instagram, Twitter) allows them to experience destinations without physically visiting them. Online platforms play a key role in destination branding by creating an immersive environment that helps users form memorable impressions (

Khan & Fatma, 2021).

The construct of brand experience was first introduced by

Brakus et al. (

2009), who argue that it ‘‘include specific sensations, feelings, cognitions, and behavioral responses triggered by specific brand stimuli. For example, experiences may include specific feelings, not just an overall liking’’ (

Brakus et al., 2009, p. 53). Initially,

Brakus et al. (

2009) proposed a comprehensive model that captures four essential dimensions of destination brand experience: sensory, affective, intellectual and behavioral.

Barnes et al. (

2014) first applied this theoretical concept to destination brands, focused on the concept of destination brand experience.

Previous research suggests that customer experience also encompasses a social dimension (

Verhoef et al., 2009). The way tourists interpret the social aspect of the ODBE reinforces recent findings emphasizing the importance of social presence in shaping meaningful online brand experiences (

Bleier et al., 2019). Subsequently,

Jiménez-Barreto et al. (

2019) extended the four-dimensional brand experience scale and proposed two other dimensions that deepen the understanding of an ODBE: interactive and social. Their results indicate that the ODBE involves a more complex set of dimensions, as it reflects the way tourists process brand-related stimuli and engage in simulated experiences within online environments, particularly during the pre-visit phase. However, in a subsequent study,

Jiménez-Barreto et al. (

2020) employed the four-dimensional brand experience scale created by

Brakus et al. (

2009) when they studied the effects of ODBE on users’ behavioral intentions toward the destination when users navigate destination platforms.

Jiménez-Barreto et al. (

2019) demonstrated that sensory and cognitive experiences resulting from engagement with official destination websites positively influence tourists’ attitudes and their intention to visit and recommend the destination. Similarly,

Lin et al. (

2024) showed that the sensory and affective dimensions of brand experience significantly impact tourists’ visit intentions. In the context of ecotourism, where authenticity and sustainability are core values, ODBE plays an even more important role in shaping decisions and promoting the sharing of destination information, thereby enhancing organic promotion through user-generated content.

Köchling (

2020) went beyond the brand focus and analyzed pre-travel ODBEs among German millennials in a qualitative multi-method approach. Consistent with other scholars (

Beritelli & Laesser, 2018;

Kladou et al., 2017;

Tasci, 2011),

Köchling (

2020) argued that the complexity of tourist destinations impedes destination branding and challenges ODBEs. The findings of her explorative study showed that the ODBE dimensions considered so far need to be complemented by a spatio-temporal dimension (perceived accessibility of expected experiences and experience density in the destination) and a social dimension. The social dimension of ODBE involves interactions with locals, other tourists, and travel companions, influencing on-site experiences and perceptions of prestige. Given the increasing complexity of these interactions, previous research recommends further exploring this evolving aspect of brand experience (e.g.,

Andreini et al., 2019;

Jiménez-Barreto et al., 2019;

Köchling, 2020).

Furthermore,

Köchling and Lohmann (

2022) suggest that pre-travel ODBEs have particularities such as a spatio-temporal component and higher interrelation of singular experience aspects, and a more context-specific measurement instrument is needed. They proposed two interrelated experience dimensions—hedonic and utilitarian—which can be explained by the dual-process theory (

Holbrook & Hirschman, 1982) and have also been used to explain general website performances (

Huang, 2005). Items expressing sensory and affective aspects as well as space-time aspects are included in the hedonic dimension, which is especially reliant on the online experiential design (e.g., video, pictures) (

Köchling & Lohmann, 2022). The utilitarian experience value includes an assessment of the anticipated destination experience’s benefits, encompassing intellectual, behavioral, and affective components (

Köchling & Lohmann, 2022).

We can conclude that ODBE is a multidimensional construct that requires specific measurement tools and its testing in various contexts and destinations (

Barnes et al., 2014;

Jiménez-Barreto et al., 2019). Therefore, the present paper proposes a scale for the measurement of OBDEs, adapted to the specificities of ecotourism destinations, aiming to enhance the understanding of the dimensionality of this construct in the context of Romania.

2.3. Model Development and Hypotheses

This research seeks to reassess the dimensionality of the ODBE construct and further the development and validation of a measurement tool. The ODBE was conceptualized as a construct consisting of 32 items based on insights from two preliminary studies (

Jiménez-Barreto et al., 2020;

Köchling & Lohmann, 2022), covering various aspects of the experience (sensory, affective, intellectual, spatio-temporal, social, and behavioral). Specific items that explore the unique online experience of ecotourism destinations have been added by the authors to each dimension, which represents a novel approach to this research (see

Table 1). These specific items for ecotourism destinations have been proposed by the authors, based on the principles of ecotourism formulated by the

Association of Ecotourism in Romania (

2025).

Previous research confirmed that ODBE is a significant determinant of visitor outcomes, specifically intention to revisit and intention to recommend (

Barnes et al., 2014). According to

Jiménez-Barreto et al. (

2020), users who had not yet visited a destination placed greater emphasis on their ODBE when shaping their behavioral intentions compared to those who had already been there. Research adopting an experiential perspective on users’ navigation of destination platforms has shown that positive online experiences—whether through websites (

Jiménez-Barreto et al., 2019;

S. Lee et al., 2018;

W. Lee & Gretzel, 2012) or social media (

Boley et al., 2018)—play a crucial role in influencing users’ intentions to visit. Moreover, recent studies highlight that engaging social media interactions with a destination significantly predict users’ likelihood to visit and recommend it (

Boley et al., 2018).

Jiménez-Barreto et al. (

2020) emphasized that visual stimuli, such as videos and images, are key drivers of sensory ODBEs but require engaging content to effectively motivate travel. Additionally, digital simulations on social media complement physical experiences, reinforcing visit intentions (

Jiménez-Barreto et al., 2019). Social media further amplifies ODBE’s impact by shaping destination image and influencing travel decisions (

Molinillo et al., 2018). Destination marketers can enhance tourist involvement and trust by providing user-friendly, engaging content and encouraging participation, particularly in cognitive aspects such as infrastructure, safety, and sustainability. Aligning social media communication and product development with shareable destination characteristics strengthens a destination’s online appeal.

Henceforth, the present study proposes the following:

H1: ODBE positively influences users’ intention to visit the destination within the next two years.

A positive online user experience not only drives visit motivation but also plays a key role in destination recommendation (

Zhang et al., 2018).

Khan and Fatma (

2021) highlighted a positive association between ODBE and word-of-mouth regarding the destination.

Mariani et al. (

2016) found that visual content strongly influences engagement, as tourists are drawn to images of destinations they have visited or plan to visit. Additionally, visual content and the average length of posts positively impact user interaction on social media. The intention to share information about the destination must be analyzed, as it significantly contributes to the pre-travel experience of other Facebook users. This study, therefore, proposes the following:

H2: ODBE positively influences intention to share information about the destination.

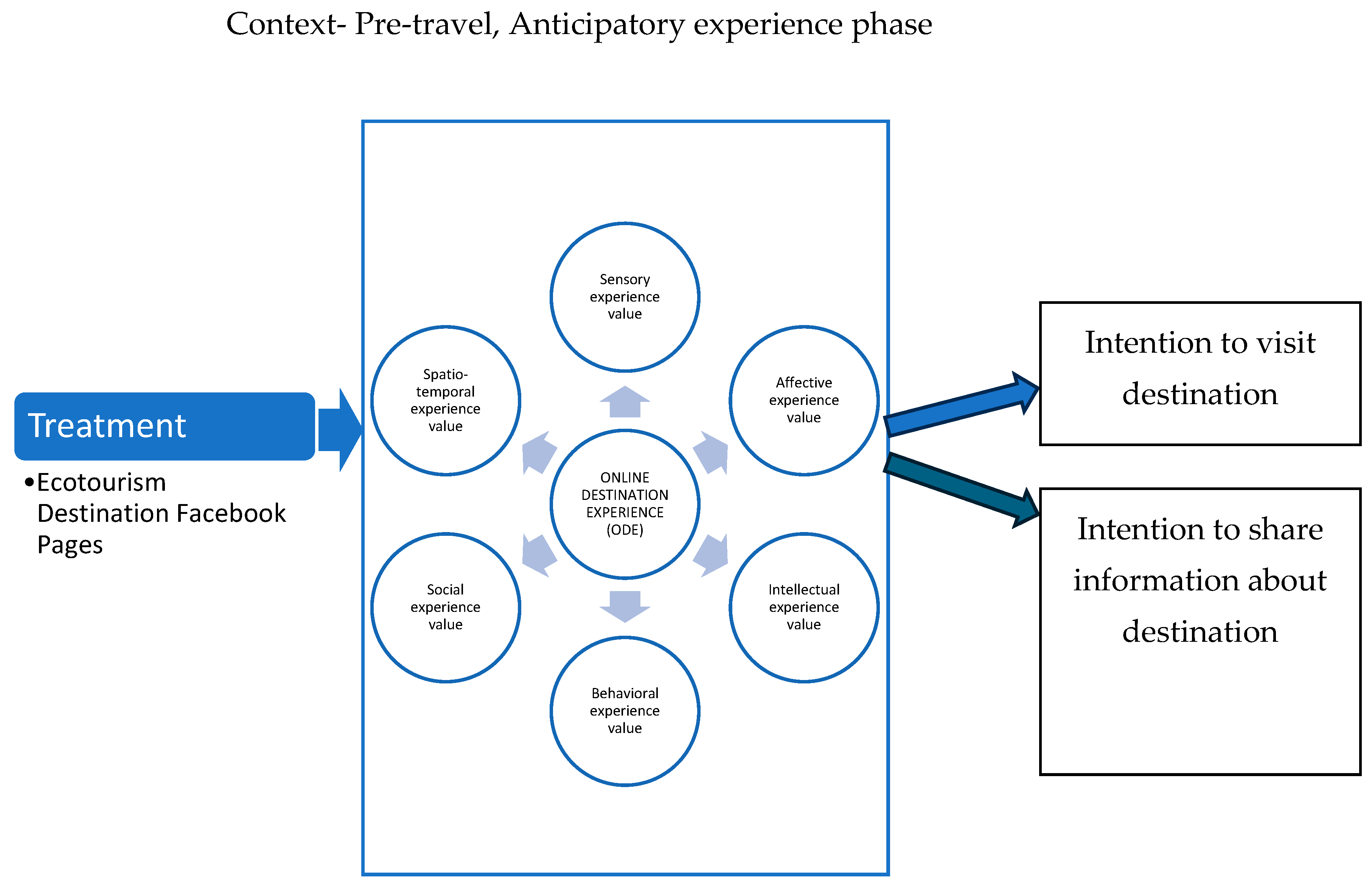

The comprehensive conceptual model is presented in

Figure 1 and will be discussed in the following section.

This model illustrates how ODBE for ecotourism destinations—operationalized through six dimensions (sensory, affective, intellectual, social, behavioral, and spatio-temporal experience values)—serves as the focal “treatment” driving followers’ behavioral intentions on Facebook. Specifically, enhanced ODBE increases users’ intention to visit the destination and their intention to share destination-related content with their networks. The six experience values jointly shape the overall ODBE construct, which in turn exerts direct, positive effects on both intention-to-visit and intention-to-share.