Civic Participation in Public Sector Education: A Critical Policy Analysis of the School System in Chile

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Fostering Effective Civic Participation

2.2. Civic Participation in Post-Colonial and Neoliberal Educative Contexts: The Case of Chile

2.3. Chile—A Market-Oriented Educative Landscape

2.4. Summary

3. Methods

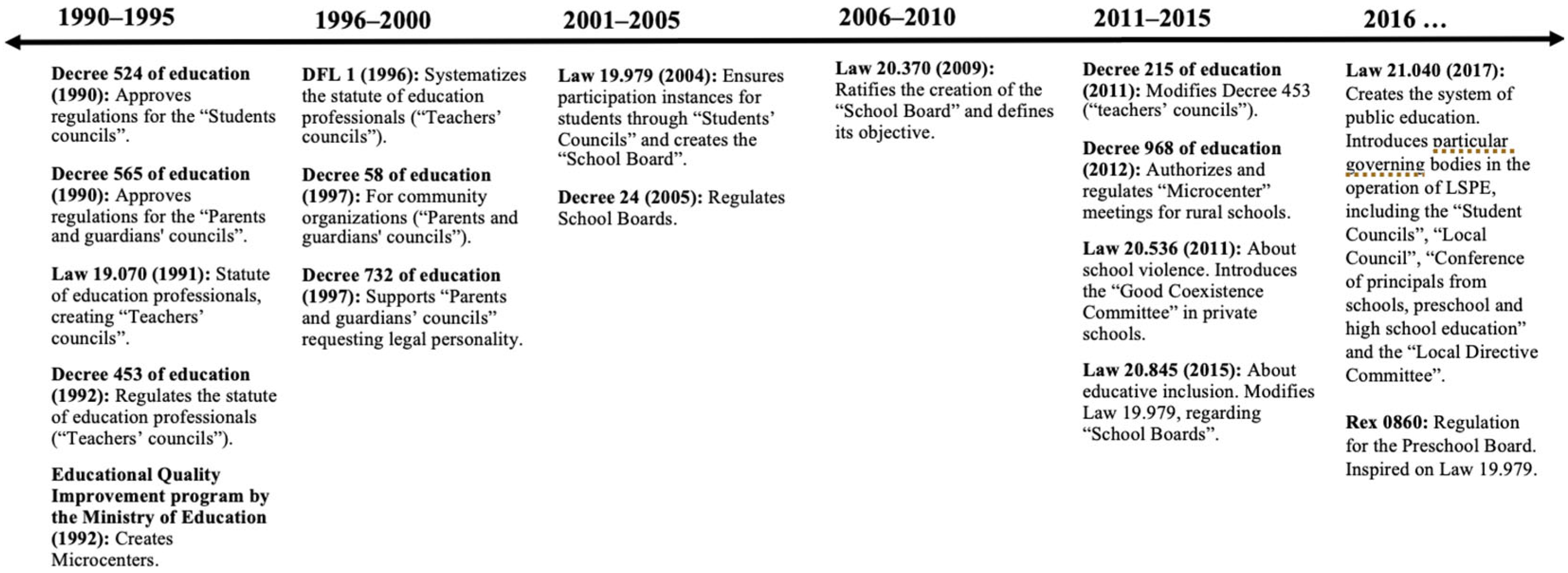

4. Results

4.1. Limited Opportunities for Collaboration

4.2. Governing Bodies’ Influence on Decision-Making Processes

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Agencia de la Calidad de la Educación. (2017). Pisa 2015: Programa para la evaluación internacional de estudiantes OCDE. Available online: http://archivos.agenciaeducacion.cl/Resultados_PISA2015.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Allan, E. (2003). Constructing women’s status: Policy discourses of university women’s commission reports. Harvard Educational Review, 73(1), 44–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, K. (2019). Tensioned threads: To read the chilean october [Hilos tensados: Para leer el octubre chileno]. Editorial USACH. [Google Scholar]

- Armijo, M., & Willatt, C. (2022). Ethics committees and shaping of children’s participation in qualitative educational research in Chile. Children and Society, 38(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnstein, S. (1969). Eight rungs on the ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Planning Association, 35(4), 216–224. [Google Scholar]

- Artaza, P. (2019). Nuestro sistema político: Miedo a lo social e ilegitimidad. In M. Folchi (Ed.), Chile despertó. Lecturas desde la Historia del estallido social de octubre. Universidad de Chile. [Google Scholar]

- Ascorra, P., Cárdenas, K., & Torres-Vallejos, J. (2021). Management levels of school coexistence at a middle level in Chile. Revista Internacional De Educacion Para La Justicia Social, 10(1), 227–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baildon, M., Sim, J. B. Y., & Paculdar, A. (2016). A tale of two countries: Comparing civic education in the Philippines and Singapore. Compare, 46(1), 93–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellei, C. (2020). La educación que se necesita instalar en la Nueva Constitución chilena. Ciper Académico. Available online: https://www.ciperchile.cl/2020/10/23/la-educacion-que-se-necesita-instalar-en-la-nueva-constitucion-chilena/ (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Bosio, E., Waghid, Y., Mathebula, T., & Banda, T. (2022). A neoliberal global south and its structural adjustment education programme (Vol. 21). Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Byker, E. J., & Vainer, V. (2020). Social studies education in Argentina: Hacia una ciudadania global? The Journal of Social Studies Research, 44(4), 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cademartori, J. (2002). Neoliberalismo y globalización en Chile. In La globalización económico financiera. Su impacto en América latina (pp. 371–376). CLACSO, Consejo Latinoamericano de Ciencias Sociales. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, C., & García, C. (2017). Evolution of citizenship education in Chile: Recent curricula compared. In B. García-Cabrero, A. Sandoval-Hernández, & E. Treviño-Villarreal (Eds.), Civics and citizenship, theoretical models and experiences in Latin America (pp. 17–40). Sense Publisher. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, C., Jara Ibarra, C., & Sánchez Bachmann, M. (2022). Citizenship education in Chile: Curricular orientations and teachers’ beliefs in a context of political crisis and social mobilization. The Curriculum Journal, 33(2), 314–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. (2009). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches (4th ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Da Matta, G., Richards, K. A. R., & Hemphill, M. A. (2015). Toward an understanding of the democratic reconceptualization of physical education teacher education in post-military Brazil. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 20(3), 329–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dardot, P., & Laval, C. (2013). The new way of the world: On neoliberal society. Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz, D. A., & Rees, C. J. (2020). Checks and balances? Leadership configurations and governance practices of NGOs in Chile. Employee Relations: The International Journal, 42(5), 1159–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díazgranados, S., & Sandoval-Hernández, A. (2017). The civic competence gaps in Chile, Colombia and Mexico and the factors that account for the civic knowledge gap: Evidence from the 2009 international civic and citizenship education study (ICCS). In B. García-Cabrero, A. Sandoval-Hernández, E. Treviño-Villarreal, S. Díazgranados, & M. Pérez (Eds.), Civics and citizenship, theoretical models and experiences in Latin America (pp. 155–192). Sense Publisher. [Google Scholar]

- Errázuriz, V., & García-González, M. (2021). ‘More person, and, therefore, more satisfied and happy’: The affective economy of reading promotion in Chile. Curriculum Inquiry, 51(2), 229–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falabella, A. (2020). The seduction of hyper-surveillance: Standards, testing, and accountability. Educational Administration Quarterly, 57(1), 113–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, J. C., Cohen, A. K., Maker Castro, E., & Pope, A. (2021). A systematic review of the last decade of civic education research in the United States. Peabody Journal of Education, 96(3), 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, R. (2022). How do student and school resources influence civic knowledge? Evidence from three cohorts of Australian tenth graders. Asia Pacific Education Review, 23(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, P. (1985). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Galeano, E. H. (1997). Open veins of Latin America: Five centuries of the pillage of a continent (25th anniversary ed.). Monthly Review Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher, T. (2021). Governance and leadership in education policy making and school development in a divided society. School Leadership & Management, 41(1–2), 132–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, R. L., & Suárez, A. M. (2023). Pedagogical practices and civic knowledge and engagement in Latin America: Multilevel analysis using ICCS data. Heliyon, 9(11), e21319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, A., Truscott, J., Simmons, C., Anderson, D., & Thomas, N. (2018). Exploring student participation across different arenas of school life. British Educational Research Journal, 44(6), 1029–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, G., & Carrasco, A. (2021). Chile’s enduring educational segregation: A trend unchanged by different cycles of reform. British Educational Research Journal, 47(6), 1611–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafner-fink, M., Malnar, B., & Uhan, S. (2013). The national contexts of post-national citizenship. Czech Sociological Review/Sociologicky Casopis, 49(6), 867–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, R. (1992). Children’s participation: From tokenism to citizenship [Essay]. Available online: https://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/pdf/childrens_participation.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Hart, R. (2013). The theory and practice of involving young citizens in community development and environmental care. Unicef: United Nations Children’s Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Haste, H., Bermudez, A., & Carretero, M. (2017). Culture and civic competence; widening the scope of the civic domain. In B. García-Cabrero, A. Sandoval-Hernández, & E. Treviño-Villarreal (Eds.), Civics and citizenship, theoretical models and experiences in Latin America (pp. 17–40). Sense Publisher. [Google Scholar]

- Holz, M. (2018). Servicios locales de educación y ordenamiento de establecimientos escolares. Available online: https://obtienearchivo.bcn.cl/obtienearchivo?id=repositorio/10221/26802/2/BCN__nueva_educacion_publica_y_ordenamiento_establecimientos_final.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Jara Ibarra, C., Sánchez Bachmann, M., Cox, C., & Miranda, D. (2023). The meaning of citizenship: Identifying the beliefs of teachers responsible for citizenship education in Chile. Theory & Research in Social Education, 51(3), 464–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, S. (2020). Schools for democracy? The relationship between nonprofit volunteering and direct public participation. International Public Management Journal, 24(1), 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, S. (2023). Democracy in and out of bureaucracy: Can participative management and public participation shape citizen satisfaction? International Public Management Journal, 27(2), 221–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, J. (2013). Inquiry into issues of trustworthiness and quality in narrative studies: A perspective. The Qualitative Report, 18, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, A., Millán, C., & González, G. (2024). Implementation of citizenship education policies in a Chilean secondary school: The role of new leaders. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, V., Gonzalez, P., Manghi Haquin, D., Ascorra Costa, P., Oyanedel Sepúlveda, J., Redón Pantoja, S., Leal Soto, F., & Salgado, M. (2018). Políticas de inclusion educative en Chile: Tres nudos críticos [Policies of educational inclusion in Chile: Three critical nodes]. Archivos Analíticos de Políticas Educativas, 26(1), 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luengo, P., & Jiménez-Moya, G. (2017). Good practices on civic engagement in Chile and the role of promoting prosocial behaviors in school settings. Civics and Citizenship, 241–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macekura, S. (2013). The point four program and U.S. international development policy. Political Science Quarterly, 128(1), 127–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mano, R. (2021). The institutionalization of ICT and civic participation: Evidence from eight European nations. Technology in Society, 64, 101518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcel, M. (2009). ¿Por qué la educación municipal? In M. Marcel, & D. Raczynski (Eds.), La asignatura pendiente: Claves para la revalidación de la educación pública de gestión local en Chile (pp. 33–39). Uqbar Editores. [Google Scholar]

- Mathebula, T., & Banda, T. (2022). A neoliberal global south and its structural adjustment education program: The practicality of global citizenship education in Malawi. In E. Bosio, Y. Waghid, T. Mathebula, & T. Banda (Eds.), A neoliberal global south and its structural adjustment education programme (Vol. 21, pp. 265–283). Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Mejias, S. A. (2012). NGOs and human rights education in the neoliberal age: A case study of an NGO-secondary school partnership in London [Doctoral dissertation, Institute of Education, University of London]. Available online: https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10020701/ (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Michail, S., Baird, K., Fattore, T., & Grace, R. (2023). Operationalising children’s participation: Competing understandings of the policy to practice ‘gap’. Children and Society, 37(5), 1576–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R., & Brewer, J. (2011). Trustworthiness Criteria. In M. S. Lewis-Beck, A. Bryman, & T. Futing Liao (Eds.), The SAGE encyclopedia of social science research methods. SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mineduc. (2017). Política de participación de las Familias y la comunidad en instituciones educativas [Family and community participation policy in educational institutions]. Available online: https://convivenciaparaciudadania.mineduc.cl/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Politica_de_Participacion_FamiliasyComunidad.pdf (accessed on 23 May 2025).

- Mineduc. (2018). Ciclo de mejoramiento en los establecimientos: Orientaciones para el plan de mejoramiento educativo 2018. Available online: https://www.mineduc.cl/wp-content/uploads/sites/19/2018/02/PME-2018-Orientaciones-27-feb.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Mineduc. (2022). Datos abiertos. Matrícula Por estudiante. Available online: https://datosabiertos.mineduc.cl/matricula-por-estudiante-2/ (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Moreno-Doña, A., & Jiménez, R. G. (2014). Dictadura chilena y sistema escolar: A otros dieron de verdad esa cosa llamada educación. Educar Em Revista, 51, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muleya, G. (2020). Curriculum policy and practice of civic education in Zambia: A reflective perspective. In A. Peterson, G. Stahl, & H. Soong (Eds.), The Palgrave Handbook of Citizenship and Education (pp. 185–194). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto, D. (2018). Citizenship education discourses in Latin America: Multilateral institutions and the decolonial challenge. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 48(3), 432–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa, A. (2022). Participación y convivencia, relación necesaria para construir nuevas formas de ser y hacer en la escuela [Participation and coexistence, a necessary relationship to build new ways of being and doing at school]. In P. Ascorra, K. Cárdenas, C. Núñez, & M. Morales (Eds.), La ciudadanía en tiempos constituyentes (pp. 83–106). Ediciones Universitarias de Valparaíso PUCV. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. (2018). Pisa: Results in focus. OECD Publishing. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1787/aa9237e6-en (accessed on 23 May 2025).

- OECD. (2024). Education at a glance 2024. In OECD indicators (Vol. 2024). OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwuegbuzie, A., & Leech, N. (2007). A call for qualitative power analyses. Quality & Quantity, 41(1), 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, O. A., & Segoshi, M. S. (2018). The racial mascot speaks: A critical race discourse analysis of Asian Americans and fisher vs. University of Texas. The Review of Higher Education, 42(1), 235–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poyanco, R. A. (2017). El derecho a la educación en Chile y la libertad de enseñanza. La importancia del principio de subsidiariedad. In I. Portela (Ed.), Paradigmas do direito constitucional atual (pp. 541–551). Instituto Politécnico do Cávado e do Ave. [Google Scholar]

- Raczynski, D., & Muñoz, G. (2007). Reforma educacional chilena: El difícil equilibrio entre la macro y micropolítica. Serie Estudios Socio/Económicos, 31, 1–178. Available online: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=55130507 (accessed on 30 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Raczynski, D., & Salinas, D. (2008). Fortalecer la educación municipal. Evidencia empírica, reflexiones y líneas de propuesta. In La agenda pendiente en educación. Profesores, administradores y recursos: Propuestas para la nueva arquitectura de le educación chilena (Issue 2003). Universidad de Chile. [Google Scholar]

- Rumié Rojo, S. A. (2019). Chicago Boys in Chile: Neoliberalism, expert knowledge, and the rise of a new technocracy. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Políticas y Sociales, 64(235), 139–164. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz, W., Ainley, J., Fraillon, J., Losito, B., & Agrusti, G. (2016). IEA international civic and citizenship education study 2016 assessment framework. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, W., Fraillon, J., Losito, B., Agrusti, G., Ainley, J., Damiani, V., & Friedman, T. (2023). IEA international civic and citizenship education study 2022 assessment framework. Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

- Shon, J., & Jilke, S. (2021). The diverse effects of private competitors on public service performance: Evidence from New Jersey’s school system. International Public Management Journal, 25(5), 722–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siches, I., & Bellei, C. (2022). Ciudadanos, no clientes. Paidós. [Google Scholar]

- Somma, N. M. (2022). Social protests, neoliberalism and democratic institutions in Chile. Canadian Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Studies/Revue Canadienne des Études Latino-Américaines et Caraïbes, 47(3), 436–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, P. (2022). La contradicción del espacio público: Educación, ciudadanía y racionalidad neoliberal en Chile [The contradiction of the public space: Education, citizenship and neoliberal rationality in Chile]. In P. Ascorra, K. Cárdenas, C. Núñez, & M. Morales (Eds.), Educación para la ciudadanía en tiempos constituyente (pp. 59–82). Ediciones Universitarias de Valparaíso. [Google Scholar]

- Steger, M., & Ravi, R. (2010). Neoliberalism: A very short introduction. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Torres Madroñero, E. M., Ruiz Botero, L. D., Pineda Rua, C., & Torres-Madronero, M. C. (2021). Peace education in contexts of transition from armed conflict in Latin America: El Salvador, Guatemala, and Colombia. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 27(2), 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treviño, E., Morawietz, L., Villalobos, C., Villalobos, E., & Centro de Estudios de Políticas y Prácticas en Educación (Chile). (2017, November). Educación intercultural en Chile: Experiencias, pueblos y territorios (Issue November). Ediciones UC. [Google Scholar]

- Tzankova, I., Prati, G., Eckstein, K., Noack, P., Amnå, E., Motti-Stefanidi, F., Macek, P., & Cicognani, E. (2021). Adolescents’ patterns of citizenship orientations and correlated contextual variables: Results from a two-wave study in five european countries. Youth and Society, 53(8), 1311–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, A. (2004). Redefining citizenship for the 21st century: From the national welfare state of the UN global compact. International Journal of Social Welfare, 13(4), 278–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walzer, M. (1993). Exclusion, injustice and the democratic state (pp. 56–64). Available online: https://www.dissentmagazine.org/article/exclusion-injustice-and-the-democratic-state (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Wilkins, A. (2012). The spectre of neoliberalism: Pedagogy, gender and the construction of learner identities. Critical Studies in Education, 53(2), 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, M. D. (1999). Multifocal educational policy research: Toward a method for enhancing traditional educational policy studies. American Educational Research Journal, 36(4), 677–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Admin. Type | School Type | Funding Type | Creation & Implementation | Student Attendance 2023 (%) 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local Service of Public Education (LSPE) | Fully public | Full public funding. | 2017–2018 1 | 4.9% |

| Department of Municipal Education (DME) | Municipal | Administered by municipalities but funded with public resources. | 1980–1986 2 | 30.8% |

| Private but subsidized | Charter school | Private ownership and mixed funding: partially private and public. | 1980–1986 3 | 54.5% |

| Private | Fully private | Private ownership and funding. | Since the XIX century 4 | 9.2% |

| English Translation Used by the Authors | Original Title in Spanish |

|---|---|

| Students’ council (SC) | Centro de alumnos |

| Parents’ Council (PC) | Centro de padres y apoderados |

| Teachers’ council (TC) | Consejo de Profesores |

| School board (SB) | Consejo escolar |

| Good coexistence committee (GCC) | Comité de Buena convivencia |

| Local School District Council (LC) | Consejo Local |

| District and School Leaders (DSL) | Comité Directivo local |

| Local directive Committee (LDC) | Conferencia de Directores de Escuelas, Jardines y Liceos |

| Governing Body | Definition | Members |

|---|---|---|

| Student Council | It aims to develop students’ reflective and critical thinking, training them for democratic life and preparing them to participate in cultural and social changes (Article 1, Decree 524). | Students. Advisors (teachers). |

| Parent Council | Supports the development and improvement of the educational processes (Article 8, Law 21.040). It aims to promote solidarity group cohesion among its members, support the provided education, and stimulate the development of the school community (Article 1, Decree 565). | Parents School Guardians |

| Teacher Council | Is a technical body in which the professional opinion of its members can be expressed (Article 8, Law 21.040) for the fulfilment of educational objectives and programs and in the development of the educational project of the educative establishment (Article 50, Decree 453). | Directive, technical-pedagogical, and teaching staff Teachers (Article 15, Law 19.070, and Article 15, DFL 1). |

| School Board | Promotes participation among different educational community members to improve the quality of education, school coexistence, and learning achievements (Article 15, Law 20.370). | School district leader (or administrative organism), School principals, A teacher elected by the Teacher’s Council, and A representative of the assistants of education (elected by colleagues). President of the Parents’ Council and President of the Students’ Council (Article 7, Law 19.979). |

| Good Coexistence Committee | [In the schools without School Councils] aims to stimulate and channel the participation of the educational community in the educational project, promote good school coexistence, and prevent violence (Part B, Law 20.536). | Student Council members Parent and Guardian Council members Teachers’ Council members |

| Local School District Council | Represents the interests of educational communities in front of the school district leader so that the LSPE considers their needs and particularities (Article 49, Law 21.040). | Two representatives of the Students’ Councils, Two representatives of the Parents’ Councils, Two representatives of assistants/professionals of education. Two representatives of leadership teams or technical pedagogic teams (elected by colleagues). A representative from local universities, ideally from faculties of education. A representative of “institutions of technical formation”, ideally non-profit and public (Article 50, Law 21.040). The LSPE’s School district leader (Article 22, Law 21.040). |

| District and School Leaders | With the Executive Director, analyzes the progress of the Local Strategic Plan. Proposes improvements for the design and provision of the technical-pedagogical support that the LSPE provides (Article 11, Law 21.040) | All school principals and All schoolteachers in charge of rural schools who depend on the LSPE (Article 11, Law 21.040) |

| Local Directive Committee | Supervises the strategic development of the LSPE and the accountability of the school district leader. It also links the LSPE with the regional government (Article 29, Law 21.040). | One or two representatives appointed by local towns’ mayors. Two representatives of the Parents Councils. Two representatives of the regional government (Article 31, Law 21.040). The LSPE’s School district leader (Article 22, Law 21.040). |

| Governing Body | Collaboration with Other Governing Bodies | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public | Private | |||

| Fully Public | Municipal | Charter | Fully Private | |

| Students’ Council (SC) | None | None | None | None |

| Parents’ Council (PC) | None | None | None | None |

| Teachers’ Council (TC) | None | None | None | None |

| School Board (SB) | SC PC, TC, District Leader, School Staff | SC, PC, TC, District Leader, School Staff | SC, PC, TC, District Leader, School Staff | - |

| Good Coexistence Committee (GCC) | - | - | - | SC, PC, TC |

| Local School District Council (LC) | SC, PC, TC, School Staff, School Leaders, Local Higher Education Institutions, District Leader | - | - | - |

| Local Directive Committee (LDC) | Locally Elected Leaders, PC, Regional Government Leaders, District Leader | - | - | - |

| District and School Leaders (DSL) | School Leaders | - | - | - |

| Governing Body | Required by Law | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public | Private | |||

| Fully Public | Municipal | Charter | Fully Private | |

| Students’ Council | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Parents’ Council | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Teachers’ Council | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| School Board | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Good Coexistence Committee | No | No | No | Yes |

| Local School District Council | Yes | No | No | No |

| Local Directive Committee | Yes | No | No | No |

| District and School Leaders | Yes | No | No | No |

| Governing Body | Level of Decision-Making Influence | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public | Private | |||||

| No Influence | Some Influence | Major Influence | No Influence | Some Influence | Major Influence | |

| Students’ Council | X | X | ||||

| Parents’ Council | X | X | ||||

| Teachers’ Council | X | X | ||||

| School Board | X*Municipal | X*Fully Public | X*PS | |||

| Good Coexistence Committee | - | - | - | X*FP | ||

| Local School District Council | X*Fully Public | - | - | - | ||

| Local Directive Committee | X*Fully Public | - | - | - | ||

| District and School Leaders | X*Fully Public | - | - | - | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alvarez-Figueroa, F.; Rees, C.J. Civic Participation in Public Sector Education: A Critical Policy Analysis of the School System in Chile. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 206. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15060206

Alvarez-Figueroa F, Rees CJ. Civic Participation in Public Sector Education: A Critical Policy Analysis of the School System in Chile. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(6):206. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15060206

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlvarez-Figueroa, Francisca, and Christopher J. Rees. 2025. "Civic Participation in Public Sector Education: A Critical Policy Analysis of the School System in Chile" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 6: 206. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15060206

APA StyleAlvarez-Figueroa, F., & Rees, C. J. (2025). Civic Participation in Public Sector Education: A Critical Policy Analysis of the School System in Chile. Administrative Sciences, 15(6), 206. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15060206