Abstract

Despite the growing prevalence of hybrid work, our understanding of its effects on employees and teams is still restricted by ambiguous and conflicting findings. We draw on findings from 11 focus groups with 48 hybrid workers from various fields to examine how hybrid work transforms teamwork and personal experience in a post-pandemic context. Drawing on paradox theory, differentiation–integration theory, and psychological needs theory, our analysis reveals that hybrid work has differential effects at the individual and team levels of analysis. At the individual level, hybrid work fosters the integration of work and family roles while hindering balanced need satisfaction in the form of role differentiation. At the team level, hybrid work preserves structural differentiation across work locations, while preventing effective integration and coordination across team roles. Based on our findings, we develop practical implications and discuss future research avenues for navigating the complex differentiation–integration dynamics of hybrid work.

1. Introduction

After the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, hybrid work has become a common work mode for organizations, giving their employees more autonomy regarding where they work (Gibson et al., 2023). Individuals and teams face complex challenges in hybrid work, such as balancing the need for individual autonomy with difficulties such as coordinating dispersed team members or dealing with delayed communication (Handke et al., 2024). In their contingency theory of organizations, Lawrence and Lorsch (1967) argue that effective organizations absorb environmental challenges by adjusting their differentiation (diversification of specialization across subunits and teams) and integration (the coordination of these units toward shared goals) mechanisms. Elevated differentiation enhances responsiveness to specific environmental demands, yet it can also create coordination challenges. Integration mechanisms are deployed to maintain systemic coherence across specialized units and teams (Lawrence & Lorsch, 1967). Their framework is foundational in understanding how organizations adapted and absorbed the challenges triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic by adapting organizational practices, structures, and communication to manage the complexity and foster collaboration across interdependent teams. The transition to hybrid work was one such adaptive response as it increased differentiation by allowing teams to operate with greater autonomy and flexibility, while simultaneously deploying new integration mechanisms, such as digital collaboration tools, revised leadership practices, and synchronized communication protocols in order to maintain alignment and coordination across dispersed, interdependent teams.

Previous literature on hybrid work, telecommuting, and virtual teams often highlights the existence of contradictory findings in terms of both positive and negative effects at the individual and team levels (Allen et al., 2015; Curșeu, 2006; Hill et al., 2022; Purvanova & Kenda, 2022; Zheng et al., 2024). The existence of such paradoxes and inconsistencies at both individual and team levels of analysis can hinder the advancement of scientific literature and the development of evidence-based practical implications.

We use a paradox lens (Lewis, 2000; Smith & Lewis, 2011) to highlight the heterogeneous findings associated with hybrid and virtual teaming (Ortiz de Guinea et al., 2012; Purvanova & Kenda, 2022). Moreover, we draw on differentiation and integration theory (Lawrence & Lorsch, 1967) to discuss our findings. In the case of individual-level findings, we also integrate psychological needs theory (Ryan, 1995; Ryan & Deci, 2017) to discuss differentiation–integration paradoxes. Considering the persistent and multi-level tensions posed by hybrid work, qualitative research is better aimed at advancing the literature (Purvanova & Kenda, 2022). We aim to gain in-depth insights into the benefits and challenges of hybrid work from a multi-level lens, exploring both individual- and team-level effects in a focus group study.

As our key theoretical contribution, we integrate paradox theory, differentiation–integration theory, and psychological needs theory and argue that hybrid work leads to opposing dynamics at individual and team levels of analysis, which create paradoxical tensions. Based on the focus group discussions, hybrid work has differential effects depending on the level of analysis. At the individual level, hybrid work is associated with decreased differentiation across roles, which hinders balanced need satisfaction as the relational and competence needs of employees are less satisfied. At the same time, hybrid work facilitates the integration of work and family roles, as these boundaries become more blurred while working from home. At the team level, hybrid work increases structural differentiation, enabling teams to better use their human resources depending on location and ensuring an adequate fit between task and technological affordances. However, hybrid work also hinders integration across team roles, being associated with coordination and communication difficulties.

As such, we contribute to the growing literature on paradoxes associated with hybrid work and answer the call for more qualitative research on virtual teams (Purvanova & Kenda, 2022). Moreover, we contribute to the literature aiming to integrate individual- and team-level conceptualizations of hybrid work (Handke et al., 2025). As our practical contribution, we advance recommendations aimed at balancing these differentiation–integration dynamics, as this may help individuals and teams deal with paradoxical tensions.

2. Theoretical Framework

Applied to hybrid work, the paradox perspective (Lewis, 2000; Smith & Lewis, 2011) posits that this work mode simultaneously brings challenges and opportunities for individuals and teams working under varying degrees of virtuality. Generally, a paradox is defined as the “persistent contradiction between interdependent elements” (Schad et al., 2016). These elements are conceptualized as paradoxical tensions or opposing forces that are interdependent and cannot be fully isolated, as they frequently conflict and interact (Schad et al., 2016). This creates a dynamic system, in which paradoxical forces constantly change and co-adapt. Moreover, as these tensions exist simultaneously, they frequently lead to contradictions and conflicting findings when analyzed as a whole (Schad et al., 2016; Smith & Lewis, 2011). Because these tensions co-exist and their core elements remain persistent, they require integrating actions and mechanisms so individuals and teams can continually adapt as a system and be able to perform and thrive under opposing tensions (Lewis & Smith, 2014; Smith & Lewis, 2011). Responses to paradoxes may entail denial, which creates a vicious cycle or negative feedback loops; on the other hand, accepting the co-existence of opposing forces has the potential to create positive feedback loops in the form of virtuous or synergic cycles (Smith & Lewis, 2011). For example, Purvanova and Kenda (2018) investigated the role of leaders in responding to the paradoxes of virtual teamwork by recognizing their existence and finding synergic solutions. Drawing on these basic assumptions, paradox theory is best targeted at informing research on hybrid work and interrelated concepts, where authors frequently note the existence of contradictory findings (Allen et al., 2015; Hill et al., 2022; Purvanova & Kenda, 2022; Zheng et al., 2024).

Hybrid work is defined as a work arrangement in which individuals switch between working from home and from organizational settings (Handke et al., 2024). In the context of hybrid teamwork, team members may switch between being fully collocated and working remotely, having fluctuating levels of team virtuality over time. This line of research has been conducted through both an individual- and a team-level lens. Concepts related to hybrid work include telework, remote work, and telecommuting, defined as employees performing work tasks from home or from a different location away from the primary office (Gajendran et al., 2024; Golden et al., 2008). Virtual work is a more global construct, describing technology-dependent employees, groups, or organizations that lack face-to-face interaction due to geographic dispersion (Allen et al., 2015). The concepts of telework, remote work, telecommuting, and virtual work have been used interchangeably in previous research, which has been conducted primarily through an individual-level lens (Allen et al., 2015; Charalampous et al., 2019). On the other hand, relevant research has also been conducted on virtual teams, primarily through a team-level lens. Virtual teams are defined as teams that are geographically dispersed and technology-dependent (Curșeu, 2006; Gilson et al., 2015; Hertel et al., 2005). Due to the conceptual overlap between these research streams, many authors point out the need to use an integrated and multi-level approach in future research (Hill et al., 2022; Raghuram et al., 2019; Zheng et al., 2024).

The tensions and contradictions described through paradox theory are frequently noted in the literature on hybrid work and related concepts. At the individual level of analysis, literature on telecommuting and remote work shows inconclusive findings regarding multiple outcomes of interest. For example, a meta-analysis by Gajendran and Harrison (2007) found that telecommuting has positive effects on perceptions of autonomy, relationship quality with supervisors, job satisfaction, and supervisor-rated job performance and negative effects on work–family conflict, turnover intentions, and role stress, while no effect was observed on self-rated job performance.

A more recent meta-analysis concludes that while remote work has positive effects on individual outcomes through autonomy, it also has opposing negative effects on the same outcomes through social isolation (Gajendran et al., 2024). Similarly, a review on the effects of virtual work on individual well-being showed mixed findings, with positive effects on well-being through flexibility and negative effects due to decreased relationship quality and boundary control, alongside increased isolation and work intensification (Hill et al., 2022).

At the team level of analysis, research on hybrid teaming and virtual work highlights difficulties such as the lack of agreement on the definition and measurement of virtuality (Zheng et al., 2024). Team virtuality has generally been linked to negative effects, such as increasing task conflict and decreasing communication, knowledge sharing, team performance, and satisfaction (Curșeu, 2006; Ortiz de Guinea et al., 2012). However, a meta-analysis by Purvanova and Kenda (2022) showed that in the case of organizational teams, virtuality does not have a clear direct effect on any team effectiveness outcomes.

Moreover, the fragmentary nature of previous research on the topics of team virtuality, telecommuting, and computer-mediated work inhibits the development of an integrative understanding (Hill et al., 2022; Raghuram et al., 2019; Zheng et al., 2024). Given these gaps, qualitative methodologies that integrate individual- and team-level perspectives have the opportunity to consider both the positive and the negative effects of hybrid work. Focus groups enable participants to share attitudes and beliefs, discuss problems and solutions, and explain their ideas to each other in an interactive fashion (Morgan, 1996). Focus groups have the advantage of capturing the spontaneous reactions of participants to each other’s ideas (Onwuegbuzie et al., 2009) and are often used to obtain a more thorough understanding of multifaceted and complex topics, such as hybrid teaming.

The COVID-19 pandemic was a major global stressor (Manole & Curșeu, 2024; Ratiu et al., 2022) that generated major transitions in the organization of work. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, flexible work arrangements were considered a benefit awarded to highly valued employees or were negotiated through idiosyncratic deals (Kossek & Lautsch, 2018; Liao et al., 2016). The pandemic accelerated the adoption of remote work arrangements (Kniffin et al., 2021), with hybrid work becoming more available and desired by the majority of workers in the post-pandemic context (Bell et al., 2023; Kilcullen et al., 2022; Nyberg et al., 2021). As remote and hybrid work becomes the norm, this poses challenges when applying pre-COVID-19 literature to hybrid work and related concepts to explain post-pandemic work experiences. Before the pandemic, the majority of research conducted on flexible work and virtuality used a dichotomous or categorical measurement approach, which could limit the generalizability of research to the post-pandemic context when a continuous approach would be more appropriate, as employees work under different degrees of virtuality (Purvanova & Kenda, 2022).

Because of these transitions, there is a growing need for more qualitative and exploratory research into virtual and hybrid work (Purvanova & Kenda, 2022). Accordingly, our main research aim was to gather insights regarding work experience in hybrid teams in a post-COVID-19 work setting. The main research questions were as follows: (1) What are the main advantages and disadvantages of hybrid work in general and hybrid teaming in particular? (2) What conditions and processes support or hinder hybrid teamwork? and (3) What strategies can be used to improve hybrid teaming?

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Focus Group Participants

We shared an invitation to participate in a focus group study through the authors’ extended social networks. We used a snowball selection procedure and included both professionals and working students. Individuals were eligible to participate if they were currently working in a hybrid team. The focus groups were conducted online using Zoom and Microsoft Teams. The focus groups were moderated by the first author and a research assistant who received formal training in qualitative research and conducting focus groups. Following preliminary analysis after each session, participants were recruited until data saturation was achieved and no new themes emerged from additional focus groups (Guest et al., 2006; Onwuegbuzie et al., 2009).

All participants were informed of the study goals when they were invited to participate and before the recordings began. We obtained informed consent from all participants included in the study. Participants did not receive any reward/remuneration for participation in the study. To ensure participant anonymity, we removed all identifying information from the transcripts, and we refer to participants using identification codes that include the individual participant number (e.g., P1) and the number of the focus group in which they participated (e.g., FG1). This study received formal ethical approval from the university’s Institutional Review Board.

We conducted 11 focus groups with a total of 48 participants (3–6 participants in each session, with an average of 4.4), with each session lasting an average of 68 min. The aim of our research was to collect data emerging from the group-level conversations. Therefore, we did not deem it necessary to collect demographic information on our participants (this also helped us to preserve full anonymity). However, in line with the procedural guidelines of focus groups, we made sure that the focus groups were heterogeneous with respect to gender and functional background. Participants worked in various domains, including human resources (18 participants), IT (13 participants), STEM (3 participants), administration (2 participants), finance (2 participants), marketing (2 participants), customer support (1 participant), management (1 participant), education (1 participant), logistics (1 participant), and other services (4 participants). They had an average hybrid work experience of 1.1 years (range 2 months–6 years).

3.2. Focus Group Protocol

Following the general procedure (Krueger & Casey, 2015), the focus groups followed a semi-structured interview protocol and used the same script. Each session began with a welcoming statement and a thank you to the participants for taking part in the focus groups. The first author explained the purpose of the focus groups, the role of the two moderators (main and supporting), general interaction norms, and the procedure used for protecting participant confidentiality, including how the analysis would be conducted. Participants were invited to say as much or as little as they felt comfortable and were encouraged to keep their cameras on to promote interaction. The main moderator encouraged each participant to respond so as not to leave out their perspective, but moderator interventions were minimal so as to maintain a natural flow to the group discussion. Participants were reminded that no names or identifiable information would be used in the written transcripts and were given time to ask any questions before giving their consent to participate and for audio recording.

We started with an icebreaker question asking the participants to describe their roles and when they started working in a hybrid work arrangement. The main questions were focused on three discussion topics: (1) individual-level advantages and disadvantages of hybrid work, (2) team-level advantages and disadvantages of hybrid work, and (3) strategies or recommendations for how hybrid teaming can be improved (see Appendix A for the full interview guide).

3.3. Data Analysis

Each focus group was digitally recorded and transcribed in full. The data analysis followed the thematic analysis procedure described by Braun and Clarke (2006, 2013). Thematic analysis is a widely used and flexible procedure for identifying patterns in qualitative data and shedding light on the meaning underlying participant discourse and interaction. Focus group data were independently coded by two of the authors, who have formal training in qualitative research and thematic analysis, without using any additional software. First, each focus group transcript was read in full multiple times. Both of the authors involved in the analysis open-coded the data; initial codes were labels that helped reduce the raw data into meaningful segments (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Any disagreements between the two coders were resolved through in-person discussion. The resulting codes were then organized into themes and subthemes with relevance to the research questions, after grouping the codes by similarity. The first author reviewed and refined the themes and subthemes to ensure that all internal codes represented the themes and that the themes were sufficiently heterogeneous (Braun & Clarke, 2006). The themes that were either not well represented by internal codes or did not fit with the emerging framework were dropped. Finally, the resulting list of themes, subthemes, contributing codes, and supporting quotes was reviewed by all the authors (for an example of an overarching theme and its supporting codes, see Appendix B).

4. Results

4.1. Advantages and Positive Effects of Hybrid Work at the Individual Level of Analysis

Some of the advantages that participants discussed were related to work flexibility and better work-life integration, saved commuting time, as well as enhanced productivity in remote work.

4.1.1. Flexibility and Work-Life Integration When Working from Home

A clear advantage discussed in all the focus groups was the importance of work flexibility. Flexibility related to work schedule enables them to organize their tasks and sometimes even choose when to work, while flexibility related to work location enables them to work from anywhere.

“For me, the biggest advantage is that it allows you to organize your schedule around personal needs. It allows you to have […] an hour’s break if you need to go for a medical check-up, shopping, to the bank or whatever, it’s much easier to accommodate your personal life during your working hours when you’re on this hybrid system”.(P1, FG9)

Work flexibility when working remotely enables participants to work in a more comfortable or relaxing setting associated with less formality, pressure, or constraints compared to the office. Moreover, flexibility enables participants to better integrate their careers with their personal lives.

“I think I have a lot of benefits regarding hybrid work, for me it also means paying attention to work-life balance, to my personal life. For example, I have moments when I’m very tired and I want to take a longer break, we also have flexible working hours, and then I allow myself to be at home, even to do a power nap and I put myself on out-of-office, and then I come back to work in force and finish the tasks. At the office we have a nap zone, but it’s not the same as at home, and the fact that I have the freedom to do this work at home and to go maybe one day a week to the office helps me focus on the task and not just survive the day”.(P1, FG5)

4.1.2. Saving Commuting Time When Working from Home

In all the focus groups we conducted, participants noted and agreed on the importance of saving commuting time. The extra minutes or hours they saved were mostly used for rest, personal tasks, or catching up with work.

“In my opinion, the biggest advantage [of hybrid work] is the fact that you can work from home, I mean you don’t have to spend time commuting to and from work, so you automatically save some hours of your life”.(P3, FG4)

4.1.3. Perception of Being More Productive When Working from Home

The majority of participants (in 10/11 focus groups) agreed that they saw positive effects on individual performance or productivity when working remotely, which they attributed to the advantages previously mentioned (having more flexibility, saving time associated with commuting to the office) but also to being in the comfort of their own home and having a quiet space to work in.

“And you’re much more relaxed, you can work more peacefully from home, there’s no crowds, no noise, you don’t even have to get ready before going to work, I find it much better from home”.(P1, FG10)

They also mentioned other factors, such as being more organized and having better time management at home, not being monitored, and not being dependent on the availability of quiet office spaces.

“I also feel more productive when I work from home sometimes, because I’m in my element and I don’t feel monitored or supervised and then I can feel at ease”.(P3, FG1)

Another key factor at play in the differences in productivity was being less distracted by their colleagues or by social interactions at work.

“I think that by working from home, you spend more time on the task at hand, you focus much more on the job because you’re not distracted by coffee breaks or other things”.(P2, FG10)

A subset of participants (in 6/11 focus groups) argued that although they were more productive, this enhanced performance was rather felt as overwork because they were given more tasks than their on-site team members or because they did not have the luxury of taking (social) breaks like their on-site colleagues.

“For example, in my team, when someone is working from home, the pressure is put on them because, as you were saying earlier, you go out for a cigarette, you go for a coffee and, for example, my job is something that you need to be present for 24/7, in case something happens. And then it puts a bit of pressure on the people at home because they’re left to cope in case we, for example, go out for a cigarette or something like that”.(P4, FG2)

This was in contrast to some participants in two other focus groups who thought on-site led to more work, attributed to being given additional tasks by their managers or leaders who were also working from the office, or to having to cover for their remote colleagues.

“If there are tasks that need to be done on-site and the whole team is not present, of course, a larger volume [of tasks] will be distributed to the remaining colleagues and then everything becomes more overwhelming, more difficult, more challenging, especially if we are each divided on certain levels, we each have our own expertise–someone is in charge of events, someone is in charge of maintenance, someone is in charge of transportation and things like that. And then, if there are these tasks that have to be done physically, unlike [the tasks of] those who work online, we will have to take them on. Of course, we won’t have this part of getting used to the task, and it automatically works harder; there are multiple layers depending on what we have to do and it’s more difficult”.(P1, FG4)

4.2. Negative Effects of Hybrid Work at the Individual Level of Analysis

Considering individual-level disadvantages, participants discussed being less productive in remote work due to work–home segmentation difficulties, as well as feelings of isolation and missing out.

4.2.1. Perception of Being Less Productive When Working from Home

Despite the initial agreement that remote work is associated with higher productivity, some participants (7/11 focus groups) disagreed with the positive effects on performance and argued that they were more easily distracted at home and had a tendency to procrastinate. In some cases, participants mentioned procrastination as a reason for overtime work. Another hindering factor to remote productivity was the difficulty associated with work–life segmentation. Some participants perceived that working from home felt like crossing a personal boundary, especially if they “like having a designated work-space” (P4, FG3) or felt that their home was no longer a “place for relaxing” (P3, FG6).

“I thought this part about being more productive from home was really interesting. For me, it’s the exact opposite. I have more energy if I work from the office and that’s probably because at home, I work at the same desk where I also spend time on my computer and do almost nothing, I mean I watch TV shows, I watch movies, or I do something else completely and I have a tendency to be lazy when I sit on the same chair and I have to work”.(P1, FG2)

Some noted these factors as reasons for their preference to work on-site, while others said they value remote work and would not return to the office, even if it cost their performance. Participants also mentioned benefits associated with working on-site, such as better technology and office conditions (workspaces or focus rooms).

“It’s at the office where I feel that I concentrate better and that I’m much more focused on what I have to do, probably because it’s an environment that somehow supports this focus, and we work here with this very purpose. Instead, when I’m working from home, in this very room that I’m in right now, and with the bed to my right often having a break or a free hour, I go there and I seem to lose focus or interest in a particular task that I’m doing and that’s why I feel that working in the office, although it’s a bit of an extra effort to get there, seems to better support just that focus on the task”.(P2, FG11)

Some participants also noted that they work through the difficulties and find ways to focus at home and be productive, despite the distractions.

“For me, what’s a stronger disadvantage when I work from home is that, it’s not necessarily that I can’t concentrate, because I can, it’s just that a lot of side quests come in, some tasks to do on the side, or I remember thinking that I’m at home, so I’ll take 10 min and find something to clean, something to cook. It’s very hard to control myself to know that this is my work schedule, I have to take care of this and I’ll leave [everything else] for later. And it took me a long time to learn that”.(P2, FG9)

4.2.2. Feelings of Social Isolation or Missing out When Working from Home

Another theme that emerged when discussing disadvantages associated with hybrid teaming was the increased feeling of isolation or missing out when working from home. Focus group participants (10/11 focus groups) reported feeling isolated from the other colleagues who were working from the office, leading to feelings of sadness and loneliness.

“For me, when I stay at home for a longer period of time, let’s say three to four days, I already feel a kind of isolation. I mean, I need interaction with someone because...you know? You get lonely like that if you don’t see people for a couple of days at a time”.(P1, FG2)

Some participants reported a more pronounced feeling of isolation when working from home, especially if going to the office provided them with opportunities to socialize that they would have lacked otherwise.

“You can get over everything else, but it takes you very far away from people and relationships and all that is socializing, social behavior; I feel like I’ve become somehow more savage just working from home, alone, than from the office”.(P5, FG10)

Other participants also reported feelings of being avoided by their colleagues who were working on-site.

“Some people might choose the days when they know there are fewer people in the office and go then so they don’t see us. I mean, they avoid us”.(P3, FG3)

When discussing feelings of missing out, some participants mentioned missing out on informal interactions with colleagues, bonding opportunities, or being part of the organizational culture and events.

“But what we do know is that for every joke like that or every chat reply, there are other hundreds that are said in the office, there are people who have seen the message and are together talking about it. That brings a much greater satisfaction, I think, when you go to the office, the fact that you are part of this small collective, which is also meta in some way to the message”.(P3, FG11)

Other participants reported feelings of missing out on important or interesting information, knowledge, or solutions to different problems that are only shared at the office and that “might prove useful in the future”.

“A disadvantage is that you miss the technical discussions [...] In the office, they discuss all kinds of solutions to problems, to bugs, and if you’re not in the office, you actually miss out when two colleagues discuss something very interesting that, I don’t know, maybe would help you, and you feel left out”.(P5, FG2)

4.3. Positive or Mixed Effects of Hybrid Work at the Team Level of Analysis

Considering team-level effects, participants discussed the need for constant connectivity and responsiveness between colleagues that have positive effects on teamwork, as well as seeing mixed effects regarding team coordination.

4.3.1. Enhanced Connectivity and Responsiveness

The importance of constant connectivity and responsiveness of team members was a theme discussed in the majority of focus groups (9/11 focus groups). When discussing whether hybrid work affected teamwork and task accomplishment, the participants argued that they saw no negative effects or even enhanced team performance and attributed these effects to the constant connectivity and responsiveness of team members. For example, they managed to solve problems or prevent coordination blockages if their colleagues were accessible through online communication, even when working flexibly from home or other locations. When connectivity or responsiveness was not mentioned as an important factor, it was discussed as something that needed improvement in the future.

“For us, it’s very cool that we are a team of fresh graduates, I mean, we are all young and restless, and we have no problem calling each other anytime and at any hour. [It’s the] same with the mentors we had, they answer to us almost instantly to any problem, even if our mentors are in [one city] and we are all in [another city] it’s not a problem at all, I mean when we go to the office and they are in at home, it’s exactly the same thing. Cheers to Teams!”(P2, FG1)

Especially when working in geographically dispersed teams, in cases of high task interdependence, and when important team members or leaders were out of the office, constant connectivity was seen as an advantage of hybrid work.

“I believe that hybrid work becomes imperative when you need that team member who is available at that moment, but only [virtually], for a crisis situation. Otherwise, I don’t think it’s necessary except if it’s the work format chosen by both the company management and the employee, seeing it as an advantage. But from a managerial point of view, so to speak, this seems to me that a situation where hybrid work, being accessible from anywhere, is necessary is when you really need that team member because of deadlines, or tasks that only they can do”.(P4, FG8)

4.3.2. Mixed Effects on Coordination

Participants who mentioned coordination difficulties (6/11 focus groups) attributed them mostly to team members not being responsive enough in online communication, or to the misalignments created in formal or informal availability hours when team members were working flexibly from home.

“It is really effective when there are meetings on [Google] Meet. It’s just that when I worked, I had flexible hours and we didn’t all get to meet. We all worked the same hours, but sometimes the people who were supposed to help me with a certain task didn’t work right then, and so they would also delay me a lot. And when they were working, I probably wasn’t working, so it wasn’t as efficient”.(P3, FG8)

“At least in my case, problems arise in terms of organization. When we’re on-site, it’s easy to bring several people together and explain to them exactly how we have to divide the tasks, whereas online, we have to depend on everyone’s availability, everyone’s connection”.(P3, FG7)

On the other hand, participants (6/11 focus groups) also mentioned positive effects on coordination due to hybrid work, such as being able to work with colleagues from different locations and increasing their ability to self-organize faster. They argued that hybrid work enables them to finish their tasks much faster, with on-site colleagues performing tasks that are social or require their presence, while colleagues who were working remotely are performing other back-up tasks from home.

“In my case, in addition to having to somehow manage the transportation that the drivers do, we also have to look for opportunities to collaborate with other companies that need transportation, and somehow we split [the work]. Those who work [from home] are actively looking for opportunities, and those who work on-site go and check if those collaboration opportunities are feasible. And this helps productivity because it streamlines our work. There’s no need for everyone to deal with the same tasks”.(P5, FG7)

“The biggest advantage is that we could work on two fronts simultaneously without having to be overwhelmed by the amount of tasks”.(P1, FG4)

4.4. Negative Effects of Hybrid Work at the Team Level of Analysis

Despite seeing some positive effects of hybrid work at the team level in terms of team effectiveness and coordination, the majority of participants noted negative effects such as reduced informal communication, communication difficulties, reduced familiarity and cohesion, and negative effects on learning.

4.4.1. Communication Difficulties

The next theme we uncovered was related to the frequent communication difficulties experienced in the context of hybrid or virtual work. This theme was particularly prominent and widely discussed, and many participants agreed that it represents a drawback to working in hybrid teams. In all the focus groups we conducted, participants discussed various communication difficulties they were facing. Slow or poor communication was identified as a problem, especially when the task was interdependent or when they needed help or feedback from colleagues or supervisors who were working in another location.

“I would say that work is made somewhat more difficult precisely because communication is more difficult. Now, working in a team often involves very interdependent tasks, and the very fact that you may need information from your colleagues, which may be delayed in coming in, would make it more difficult or more time-consuming to accomplish tasks”.(P1, FG9)

In some cases, participants attributed these communication difficulties to the delays associated with using text-based or asynchronous communication, technology barriers or constraints in virtual meetings, overload from using too many communication channels at once, and virtual meeting fatigue.

“A problem occurred when one of the new employees was working from the office, they were performing their task and needed some urgent information from another colleague with more experience but who was remote, not working at the office at the time, and they didn’t answer. In fact, they answered, but with a rather long delay. So the information arrived, but too late to help him”.(P3, FG7)

Another factor that led to frustration was misalignment with the colleagues who were working remotely. In other cases, communication problems and delays were internally attributed to their colleagues, and this perception made some participants feel like they were being ignored.

“This is a problem I’ve seen especially in big corporations, you frequently leave a message on Teams, Skype, Slack, on whatever you use, and if they don’t feel like it, they will not answer. They won’t even open your message. But if they were next to you, they wouldn’t be able to ignore you”.(P1, FG2)

Furthermore, participants agreed that online communication is frequently associated with misunderstanding of either tone or intention, which may lead to tensions between colleagues and a reluctance to ask for help in the future. Generally, the communication difficulties they identified and discussed were perceived as being solvable through face-to-face interaction.

“I find it fascinating how much these interactions can change. Two people who have known each other for a very long time, let’s say, seem to forget that they have known each other for a very long time when they make the switch to chat. And I have seen many such situations, that’s why I prefer to send either a very explicit text, or to talk about important aspects directly in person, so that there are no misunderstandings”.(P2, FG9)

Misunderstandings also arose when team members were communicating virtually and were not able to check if the team formed a shared mental model or understood instructions. Participants mentioned misunderstandings in relation to low media richness and reduced social presence, for example, when keeping their cameras off during virtual meetings.

“It has happened to me many times to pass on a piece of information to 20 people, and each one of them, or most of them, understood the information differently. It does depend a lot on who you are addressing and how you formulate the information. In online work, I often transmit a piece of information, and I explain it, but maybe I don’t explain it in such a way that the information reaches each person, and I feel the need to see them once more in a meeting and to re-transmit it”.(P2, FG10)

4.4.2. Negative Effects on Familiarity, Cohesion, and Interpersonal Relationships at Work

Participants mentioned dealing with colder interpersonal relationships in all focus group discussions. They discussed negative effects on social cohesion, attributed to the reduced informal interaction. For example, they mentioned rarely feeling connected to their colleagues.

“I think that working from home or too much hybrid work pushes the relationships apart [...] It’s a totally different relationship. It’s much colder, much more distant. Somehow, we’re colleagues, but it’s as if we’re not. So when you’re on-site every day, as [P3] said, you have a coffee together, you go to lunch. Somehow, you become a little closer. Not necessarily intimate, but the relationship is somehow forced by the surroundings to be closer or more trusting”.(P5, FG10).

“We have a small number of memories from the office, and we balance our relationship on them alone”.(P1, FG5)

Participants also discussed negative effects on team familiarity, such as not knowing their teammates well enough.

“I, for example, still don’t know all my colleagues. If they came to introduce themselves, I wouldn’t know if I actually communicated with them online. It happened last week. I build a certain impression of them, and when I see them in real life, they look totally different from how I imagined them to look, and it’s harder to recalibrate and relate to them on-site”.(P3, FG1)

These negative effects on familiarity and social cohesion were linked to communication difficulties (misunderstandings, awkwardness), learning barriers (not asking questions freely), or difficulties in making friends at work.

“Well, it seems to me that sometimes it’s hard to look at people behind the screen as people, if you haven’t been in the office for a very long time, and it can cause all sorts of conflicts because I fail to empathize with colleagues when they have certain problems”.(P3, FG5)

Many participants perceived that the informal interactions that help build cohesion only happen at the office. They saw positive effects on relationships after office days because of spending more time on social connection and informal interactions.

“It’s different at the office because you meet people. If you text them from home, they may choose not to answer. At the office, you see them. I think it’s a double-edged sword, [hybrid work] is different than only online or only at the office. The relationships are much more emphasized in the office because you’re not hiding in front of a screen, and you can convey something nonverbally which you probably couldn’t do from behind a screen”.(P2, FG10)

Some of the participants also noted feeling a divide between the colleagues working from home and those working from the office. On the one hand, some of the participants interpreted these fault lines as a result of better communication, feedback, helping behaviors, and cohesion between colleagues who were together on-site, while remote colleagues were left out and had access to fewer experiences and less information.

“Somehow it also contributed to the creation of sub-groups; I mean, those of us who went more to the office, we formed a tighter group, and those who stayed at home more and did more hybrid work were left out a little bit. It was a weird situation”.(P3, FG3)

“In my case, colleagues who work in the office get along better, and they help each other more. Those of us who work remotely, on the other hand, if we say in meetings that we need help, unless we ask for someone’s help, no one really offers it. But if a person working from the office asked for help, someone working from the office would certainly jump to help, because they get along better than we do”.(P4, FG7)

On the other hand, some participants interpreted the faultlines as related to delays in responsiveness of remote colleagues, or the fact that those working from home were prioritizing personal tasks over working.

“From what I’ve seen, relationships between colleagues are negatively affected. We have colleagues who, on Tuesdays and Wednesdays, are always waiting for a delivery. So there are excuses from certain colleagues. And always, on the days when we should go to the office, they are waiting for the courier. Whether that is [true] or not, we don’t know. But it’s somewhat unpleasant. Either we all respect this hybrid schedule and go to the office on Tuesdays and Wednesdays, and there are exceptional situations when we can’t, or we all find excuses like “my cat’s pregnant”, “the courier’s coming”, or something like that. These things form big gaps between us, between colleagues. To me, it doesn’t seem fair to always have excuses like that”.(P1, FG1)

4.4.3. Negative Effects on Formal and Informal Learning

A theme that emerged in all the focus groups we conducted was related to the difficulties some participants experienced when engaging in learning behaviors such as asking questions and seeking and receiving feedback or help. They reported that it was easier to engage in these conversations on-site, face-to-face. The difficulties associated with the reduced learning behaviors were especially detrimental in cases of high task interdependence, such as when needing an answer or piece of information to complete an ongoing task.

“There are of course times when you need to ask someone for help because you have too much workload at the moment, or you want to ask for advice or information because you don’t know a certain procedure, or things like that. I’ve noticed that these things happen much more easily when we are there, physically present at the office, than when you send a message on Teams or an email, and you wait for a reply and the information has not been well conveyed in writing”.(P2, FG11)

This negative effect was attributed to hesitating to ask for help or information online, or to communication difficulties such as delayed responses or being ignored online.

“If we’re in the office and we’re dealing with some problem, we have desks next to each other, and any one of us that has a question can just throw it in the air and there’s always a colleague who knows the answer, knows how to help, has a proposal to solve the problem, whereas if we’re working at home even if we have the Teams [chat] for friends or teammates where we could discuss these things, it goes much slower and the answers, or the accuracy, the quality of the answers is not as high as if we were working in the office”.(P1, FG1)

Many participants also discussed negative experiences or difficulties in their onboarding or early-career stage. The fact that their team members, leaders, or mentors were working from a different location was believed to be detrimental to their learning or integration. In this line of discussion, some participants argued that onboarding, learning, or mentoring should be carried out on site to facilitate communication and help new hires familiarize themselves with the team, organizational culture, processes, and tools.

“Onboarding was hard for me, I was just starting out and didn’t know a lot of things that I had to learn. Compared to being at home, it would have been much more effective if I had worked more at the office so that I could learn much faster and understand exactly what I had to do. I picked up some things that seemed to be quite easy, but I picked them up with more difficulty from home, and if I had been physically in the office, I think it would have been much more effective”.(P3, FG8)

4.4.4. Reduced Informal Communication and Enhanced Focus on Taskwork

Many participants (in 8/11 focus groups) discussed a tendency to focus more on the task and less on informal conversations when working from home or in hybrid meetings.

“I have noticed that when working from home office, people seem to be much more focused on work. I mean, yeah, ok, we have to do our work, but the conversations are so much drier, we only talk about what we have to do, and when we are in the office, we laugh, we joke, we do something that is somewhat off-topic. But online it’s just question-answer, question-answer, and the main topic is just work; I don’t know, I think it depends on the day, and people’s moods, but in general, that’s what I’ve noticed. Personally, I miss this part of the joking around, sending someone a funny gif or a meme or something”.(P5, FG1)

Although the conversation seemed drier, colder, and more impersonal, this lack of informal discussions in online communication was seen as an advantage, as it made it easier for team members to focus on the task and be more productive. Giving fewer resources to informal interactions enabled them to finish their tasks faster and more efficiently.

“From a positive point of view, I think we are much more efficient and we have a much more efficient time management, because we don’t waste time with other discussions than we would face-to-face”.(P2, FG7)

However, participants noted that informal communication should be improved in order to work more effectively in a hybrid team setting. When discussing possible solutions, they mentioned the importance of proactivity in stimulating informal discussions during meetings and scheduling informal meetings or events.

“In addition to what the girls have already said, which I think is very good, I would also add paying attention, not only to work-related communication, so to speak, but also purely to socializing. This is something that I was mentioning before the pandemic, too. To have at least half an hour a week where you meet, even if it’s in a Teams meeting, but to just chat about random things, to get your mind off work, and only talk about getting all the tasks done”.(P1, FG9)

4.5. Contingency of Task Characteristics

Considering team tasks, participants believed that complex and interdependent tasks that require debates, task conflict, negotiation, decision-making, as well as transition processes (such as strategy formulation and goal setting) are better performed when all team members are present at the office.

“Certainly, hybrid work has an influence depending on the complexity of the tasks. Everyone finds it even harder, probably when time pressure comes in, when you have deadlines. And as [P3] also said, especially if not everyone is synchronized on work at the same time and you depend a lot on colleagues to go on with your task. So, you can work, you can accomplish the tasks of a team by working in a hybrid format, but not totally, I mean you can’t have the whole team working in a hybrid format. I estimate somewhere around 30 percent of the team. When you’re talking about more than that, you’re going to have time issues, time lags”.(P4, FG8)

They also believed that on-site work is for social interactions and learning, while work from home is better suited for complex tasks requiring individual work and concentration—tasks that are independent from those of team members. Some participants argued that a team task should first be approached from the office, with all team members present, and later, individual work can be completed from home.

“Yes, decision-making processes necessarily require a physical meeting. Maybe, for example, we want to think about an internship program or a new project. Automatically, we need decisions, an opinion from each member, to meet somewhere to discuss, and then to decide, and only later to start implementing the project in an online or hybrid format. It’s not really feasible otherwise, it’s rather inefficient”.(P1, FG8)

4.6. Managing the Negative Effects of Hybrid Teaming

In almost all the focus groups we conducted (10/11), some participants had a different perspective and mentioned that they saw no negative effects on either relationships or team performance due to team characteristics, processes, or norm-setting. They discussed being well-organized, using communication norms, having regular meetings, and using supportive technology. Other participants discussed a lack of negative effects due to low task interdependence, having built familiarity and cohesion after initial face-to-face interactions, or spending time together at the office.

“In terms of communication, we didn’t feel a disadvantage because we are always in meetings and talk about whatever comes up, and we are very receptive there for each other”.(P1, FG3)

Many of these details were later discussed as interventions that would improve hybrid teamwork or mitigate its negative effects, such as using proactive relationship building, norm-setting, informal communication, and affect management.

4.6.1. Introducing Team and Organizational Norms

When discussing strategies or potential interventions to help mitigate the negative effects of hybrid work, participants (in 10/11 focus groups) argued that organizations should set norms for face-to-face meetings, formal or informal, such as office days or office events, where all team members should be present. Participants believed such interventions would help increase cohesion and familiarity and reduce social isolation and the fault lines between remote and on-site colleagues. Some participants argued that these events should be mandatory to promote interaction, while others believed they should be recommendations.

“It works very well for us that we have 2 days a week on-site and then everyone is there. It’s different, totally different than if everyone went [to the office] when and how they wanted”.(P1, FG1)

They also proposed team norms, such as setting clear communication rules or choosing their office days together.

“Working from home or hybrid, in the hours when tasks are assigned we should be present as much as possible, set a time in which we can allow ourselves to be late with an answer, say 15–20 min, and the other [colleagues] should signal whether it is urgent or not to receive that information, so that we know how to manage ourselves in the future”.(P3, FG7)

Participants also discussed the importance of transparent and agreed-upon availability hours or increasing team accountability to reduce delays in communication and minimize frustration and coordination difficulties.

“What I would add […] would be that those who work remotely should respect working hours. In other words, when there are working hours, those who are remote should actually work in those hours and not do something else, which would affect the whole team”.(P4, FG7)

An intervention frequently discussed was promoting communication and relationship-building through proactive informal meetings. Although early face-to-face interactions were deemed the most important, participants proposed taking time out of the workday for both online and on-site meetings and social activities.

“I think that to work well in hybrid you need to work on-site first, to first have a head start with the team, to see people there doing their job, to have that human interaction first and then move into the work from home, and not the other way around, so you get to tie some relationships and be able to attribute clear faces to the names of coworkers, not otherwise”.(P4, FG3)

“We have introduced these online coffee breaks. Just meetings, where you sit for half an hour with a topic, like your favorite food, or how you chose the name of your pet. We were talking there too, but it was quiet at the beginning, and we said that nobody was talking. Then, a coordinator was assigned to each meeting, a colleague who tried to moderate each meeting, and somehow it gradually reduced the difference between the groups”.(P3, FG3)

Another team intervention that was discussed was increasing psychological safety; participants mentioned the importance of being able to ask for feedback or ask “stupid questions” without fearing that they would be judged or being able to make mistakes or learn while receiving helpful and nonjudgmental feedback.

“I would add having sessions where you can also express your annoyances or things that bother you, and this can be done either in teams or between two people, because you may not feel comfortable voicing certain things to five people, but you feel comfortable doing it to one or two. And I think that’s quite important”.(P1, FG9)

4.6.2. Affect Management Processes

In about half of the focus groups we conducted (6/11 focus groups), participants also mentioned the importance of affect management, with behaviors such as using humor, gossip, or discussing their frustrations and problems openly in a meeting. These techniques helped them build cohesion and mitigate the negative effects of distance on social connection.

“I think humor is the main thing that keeps us connected. And gossip, as strange as it sounds. Whenever we walk into a meeting and there are 150 employees and 30 managers minimum, because in economics there are always managers and managers, they always have their camera on and we gossip about them—if he’s going to the gym, if someone else shaved his head—and it keeps us together as a team. We didn’t talk a lot at the beginning, I was ashamed, and so I started to interact with them, and I saw from the first call that they started to talk, and actually there were nice things that bonded us”.(P2, FG4)

5. Discussion

We integrate our findings using a systemic multi-level perspective building on two key concepts, namely differentiation and integration. Work design literature has long emphasized that effective team and organizational functioning requires an efficient balance of differentiation and integration mechanisms (Lawrence & Lorsch, 1967). In order to effectively manage increasing levels of environmental complexity and uncertainty, (organizational) systems segment and diversify their units through differentiation mechanisms, resulting in higher internal complexity. This response brings challenges in coordinating the system, which requires integration mechanisms. Overall, adaptive and effective social systems require high levels of both differentiation and integration mechanisms (Lawrence & Lorsch, 1967).

Building on our findings from the focus groups, we derive two paradoxical effects of hybrid work on differentiation and integration at the team and individual levels. We argue, as our key theoretical contribution, that the paradox of hybrid work is that it fosters role boundary integration while hindering role and need differentiation for individual team members, yet it preserves structural differentiation across work locations and prevents effective integration across roles at the team level. At the team level of analysis, balancing differentiation and integration is essential for task allocation and creating conditions for synergistic action (Curșeu, 2006), while at the individual level of analysis, balancing differentiation and integration across life domains is essential to lead a fulfilling and meaningful life (Pluut et al., 2025).

Consistent with previous research on psychological needs theory and extending the principle of differentiation and integration from social systems to individual employees, we argue that a similar balancing between differentiation and integration across life domains (work, family, leisure) grounds a happy, fulfilling, meaningful, and successful life (Pluut et al., 2025; Ryan, 1995; Ryan & Deci, 2017). In the context of individual-level effects of hybrid work, the flexibility of working from home fosters integration between work and family life domains, yet it precludes the segmentation or differentiation of roles that are equally essential for fulfilling autonomy (related to environmental mastery, volition, and psychological freedom), competence (related to personal growth and effectiveness), and relatedness needs (related to social connectedness) (Ryff & Keyes, 1995; Sheldon & Niemiec, 2006). Employees thrive when their needs are simultaneously fulfilled (Sheldon & Niemiec, 2006) due to their engagement in distinct and differentiated social roles that allow them to take unique family and friendship roles, excel at work, and entertain personal hobbies. Theories in positive psychology stipulate that differentiation across life domains allows employees to develop sources of meaning and cultivate their resilience, while effective integration ensures meaning coherence and alignment with personal values and beliefs (Ryff & Keyes, 1995).

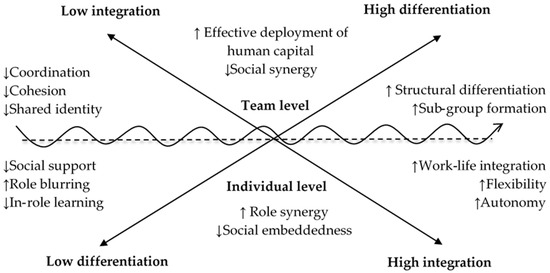

At the team level, the general consensus stemming from our focus groups, which aligned with claims from previous literature (Curșeu, 2006; Handke et al., 2024), is that hybrid work fosters work differentiation, yet it precludes integration. In other words, by relying on hybrid work, teams can fully capitalize on highly diversified and dispersed human resources by increasing the functional specialization of employees working from different locations (remote vs. on-site). On the other hand, hybrid teams frequently face challenges in synchronizing or coordinating actions across employees working from different locations. For example, teams may face communication difficulties, misalignments, and coordination demands, with negative effects on relational dynamics and task accomplishment (Curșeu, 2006). We present our proposed framework in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

A multilevel framework for the differentiation–integration paradox of hybrid work. Legend: ↑ = increased; ↓ = decreased; oscillating arrow depicts the dynamics nature of the differentiation–integration paradox of hybrid work, as embedded in the cross-level interplay of individual- and team-level effects.

5.1. Differentiation and Integration Mechanisms–Individual-Level

Previous research highlights the importance of balanced need satisfaction for increased psychological well-being, motivation, and performance (Gillet et al., 2019; Milyavskaya et al., 2009; Sheldon & Niemiec, 2006; Van den Broeck et al., 2016). Based on these studies, the most satisfied individuals are those who maintain a balance between discrete need fulfillment instead of prioritizing one need over the others. We acknowledge that hybrid work generates some positive forms of role differentiation for individual team members, as flexible work allows them to more easily entertain a variety of social roles. However, our findings mostly emphasize the negative consequences of lacking differentiation in terms of having fewer learning opportunities through direct interaction with diverse others, experiencing restricted informal social contact with teammates, and having fewer diverse options for effective and authentic affect management.

Drawing on our focus group results, hybrid work seems to enable the satisfaction of autonomy needs through enhancing flexibility while preventing the satisfaction of relatedness (through social isolation and lack of informal interactions) and competence needs (through diminished learning experiences). While fulfilling the need for autonomy, hybrid work modes also decrease the enactment of interpersonal supportive behaviors for basic needs at work, primarily for competence and relatedness (Slemp et al., 2024). Previous meta-analytic findings show that need-supportive behaviors enhance self-determined motivation and have positive effects on individual well-being and performance (Slemp et al., 2024). Although the need for autonomy and autonomy-supportive behaviors has clear positive effects, we argue that hybrid work decreases the fulfillment of competence and relatedness needs as well as the respective need-supportive behaviors.

Consistent with previous findings, hybrid work is more likely to distance employees from social resources, such as knowledge sharing and informal relationships (Leonardi et al., 2024), and decrease social support and feedback (Sardeshmukh et al., 2012; ter Hoeven & van Zoonen, 2020; Vander Elst et al., 2017). Drawing on focus group findings, interpersonal supports for competence, such as providing structure and feedback, sharing knowledge, providing learning opportunities, and coaching from mentors, are reduced in hybrid work. Additionally, interpersonal supports for relatedness, such as expressing warmth, mutual concern, and fostering meaningful relationships and social connection, are diminished by the excessive focus on task accomplishment and the decrease in informal, serendipitous interactions. Our findings indicate decreases in both lateral support (from team members) and vertical support (from mentors or leaders), with negative effects on need fulfillment.

Integration is important for need fulfillment and well-being because it can bring coherence between multiple roles and identities that may have otherwise conflicting demands (Deci et al., 2017; Pluut et al., 2025). In light of the focus group results, hybrid work mostly fosters role integration for the individual team members. Role integration is facilitated as team members are able to combine work with hobbies (watching movies, TV shows), recover better by having longer breaks, allocate more time for role integration by reducing commuting time, and integrate family and work roles more efficiently (e.g., doing household chores during work breaks).

Integration enactment has been associated with both positive and negative effects. For example, integration facilitates the transitions between work and personal roles but also leads to role blurring, lack of psychological detachment from work, and work–family conflict (Allen et al., 2014; Olson-Buchanan & Boswell, 2006; Kossek et al., 2006). Consistent with our findings and with boundary theory (Ashforth et al., 2000; Kreiner, 2006), hybrid work enables role integration during work-from-home days, increasing boundary flexibility by overlapping work and home boundaries and allowing for transitions between boundaries. Moreover, hybrid work strengthens boundary permeability by increasing the voluntary or involuntary interruptions of one role in the other role’s domain and making personal demands more salient during work hours (Allen et al., 2014; Ashforth et al., 2000; Kossek & Lautsch, 2012). When working from home, role transitions may bring switching costs and interfere with work tasks, but they can also help integrate the different roles employees have, enabling them to deal with both work and personal demands (Delanoeije et al., 2019).

Drawing on our focus group findings, it is also possible that the differences in perceptions of productivity when working from home are associated with boundary management preferences (Ashforth et al., 2000; Kreiner, 2006), as most of the participants who mentioned negative effects linked them to excessive role blurring and interference, showcasing a preference for segmentation, or keeping work and home domains separate (Allen et al., 2021). Specifically, participants with segmentation preferences may be less satisfied with home-related interruptions or distractions during work-from-home days in hybrid work, especially if they fail to engage in adequate segmentation or boundary control behaviors (Kossek & Lautsch, 2012). As such, this could lead to a desire to work from the office (Shockley & Allen, 2010), where they may feel lonely or isolated if other colleagues fail to respect norms regarding office days. On the other hand, participants with integration preferences prefer to blend work and home roles and may be more tolerant of interruptions and role switches during work-from-home days (Kossek & Lautsch, 2012; Olson-Buchanan & Boswell, 2006).

5.2. Differentiation and Integration Mechanisms—Team-Level

At the team level, most of the insights that emerged from our focus groups show that hybrid work mainly facilitates differentiation as it allows teams to capitalize on the human resources that are geographically dispersed, simultaneously allocated to various projects, and have different functional or role specializations. As such, increasing differentiation through hybrid work modes enables organizations to meet the demands of the workforce and better face environmental uncertainty. Consistent with the principle of task–technology fit, teams may become more autonomous and decide to self-organize across different locations, assigning and differentiating tasks to fit their current level of technological dependence (Malhotra & Majchrzak, 2014; Maruping & Agarwal, 2004), such as tasks that require direct social interaction to colleagues working from the office, and more administrative or information-processing tasks to colleagues working from home. Drawing on our focus group findings, participants working in teams that adequately differentiated their work tasks and efforts and, later, coordinated across work locations, found hybrid teaming to be more productive.

However, most of the challenges related to hybrid work reported by our respondents focus on the negative facets of integration, as seen in coordination difficulties such as problems with synchronizing actions, lack of timely reactions to emergent critical issues or important deadlines, and difficulties experienced during online communication. Consistent with the previous literature on hybrid and virtual teams, participants discussed problems such as misunderstandings in communication and the tendency to make negative or dispositional attributions (Curșeu, 2006; Hinds & Bailey, 2003; Leonardi et al., 2024; Wilson et al., 2008). Differences in time spent together at the office may lead to collocated team members feeling closer to each other and increasing feelings of isolation in colleagues working from home, while hindering collective coordination (Handke et al., 2024; O’Leary & Cummings, 2007; O’Leary & Mortensen, 2010). Consistent with this lack of adequate integration across work locations, participants also discussed the importance of increasing boundary-spanning integration mechanisms in the form of proactive norm-setting and relationship building, team onboarding practices, informal communication, and affect management processes.

Consistent with paradox theory (Lewis, 2000; Smith & Lewis, 2011) and the perspective of teams as multi-level systems, we argue that the differentiation–integration dynamics at the individual and team levels are mutually interdependent, as members are embedded in teams. For example, team-level dynamics may have top-down effects on individual team members in the form of increasing connectivity demands as an integration mechanism, which may in turn blur the boundaries between work and family roles for individual team members would prefer to have more flexibility in their work schedules, or to disconnect from work outside work hours. On the other hand, individual-level dynamics may have bottom-up effects on teams. For example, increasing flexibility or autonomy at the individual level may lead to misalignment and communication difficulties at the team level, which would later bring relational difficulties in the form of decreased familiarity and cohesion.

5.3. Main Theoretical Implications

Our study makes several theoretical contributions by integrating paradox theory and the differentiation–integration framework to analyze how hybrid work impacts work organization and outcomes at the individual and team levels of analysis. First, we contribute to the literature on contingency theory (Lawrence & Lorsch, 1967) by showing that hybrid work creates asymmetric dynamics across the individual and team levels. On the one hand, it fosters integration and reduces role differentiation at the individual level, while on the other hand, it increases differentiation and impedes integration at the team level. This dual-level insight deepens our understanding of the multifaceted implications of hybrid work used as a modern organizational practice to adapt structurally and relationally in response to environmental complexity.

Second, our findings extend paradox theory by showing that paradoxes are not only intra-organizational tensions between competing demands, but they reflect dynamics of interdependent (sub)systems with a multilevel organization and a dynamic nature. While paradox research has traditionally emphasized the coexistence of contradictory yet interrelated elements (Smith & Lewis, 2011), our analysis shows that such tensions are not necessarily consistent across systemic levels, and they can manifest differently at the individual and team levels of analysis. Furthermore, paradoxes are also shaped by both structural conditions (e.g., task allocation, spatial dispersion) and psychological mechanisms (e.g., role identity, need satisfaction). Finally, these tensions are likely to co-vary across time and across levels, calling for multi-level and dynamic research perspectives on the consequences of hybrid work. In theorizing hybrid work through a paradox lens, we illustrate how local tensions (e.g., role blurring, autonomy) recursively interact with systemic dynamics (e.g., coordination breakdowns, fault lines), thereby refining the boundary between “micro” and “macro” level paradoxes. Our study thus contributes to an emerging strand of paradox research that views tensions not as static dyads but as nested, evolving constellations embedded within broader sociotechnical systems (Lewis & Smith, 2014; Schad et al., 2016). We call for further theorization of paradox as a multilevel phenomenon in motion, where tensions are enacted, refracted, and potentially reconciled through recursive interactions across space, time, and structure.

Third, by incorporating psychological needs theory (Ryan & Deci, 2017), we offer a nuanced view of how hybrid work affects need satisfaction. While autonomy is often fulfilled, competence and relatedness can be negatively affected, especially in the absence of strong social integration mechanisms. These results expand prior models of need satisfaction by positioning hybrid work as a differentiated experience that impacts each need domain unequally.

These theoretical contributions lay a foundation for future multi-level theorizing on hybrid work and underscore the importance of designing interventions that balance differentiation and integration both within and across organizational levels.

5.4. Practical Implications

In terms of practical implications, we argue that this emerging paradox of hybrid work and its associated managerial challenges can be effectively addressed by restoring the balance between differentiation and integration at the individual as well as the team level. Therefore, we claim that one of the key challenges of hybrid work is to foster integration at the team level while preserving differentiation at the individual level. Our study extends the insights of paradox theory (Smith & Lewis, 2011) to work design by showing that hybrid work generates enduring tensions that require effective managerial actions. Such actions should focus on the balance between autonomy versus coordination, as well as work flexibility versus social cohesion. These findings challenge linear assumptions about the differentiation and integration implications of hybrid work as a modern work design and highlight the need for dynamic, context-sensitive models that can accommodate persistent contradictions in hybrid work arrangements. We present a summary of our practical recommendations in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of findings and practical implications.

5.4.1. Foster Differentiation at the Individual Level

Our focus group results indicate the need to increase differentiation, especially in terms of social and competence needs. In order to foster the social needs of employees, organizations should create opportunities for informal and deep exchanges with colleagues, especially in the early stages of team formation, to build trust and familiarity. Considering learning and information-sharing as competence needs and previous studies that highlighted the importance of mentoring when going to the office (Handke et al., 2024), our findings indicate that these experiences may be negatively affected by hybrid work settings unless proactively planned. Accordingly, we suggest that organizations facilitate mentoring relationships and provide adequate learning experiences, especially for recently onboarded employees. The majority of our participants felt that such experiences are better implemented on-site, with the presence of colleagues, team leaders, or mentors. From a multi-level lens, such interventions would target and promote differentiation across work roles for individual employees, while also serving as integration mechanisms at the team level.

5.4.2. Reduce Excessive Integration at the Individual Level

Despite the mixed findings on the effects of role integration when working from home, more recent research points out that segmenting work–nonwork boundaries has positive effects on productivity and well-being even in the case of individuals with a preference for integration (Allen et al., 2021; Scheibe et al., 2024). Consistent with our findings, excessive role integration may lead to severe interference between work and other social roles. In light of these results, employees should proactively implement segmentation tactics during work-from-home days, such as setting a clear work schedule and availability hours and using a dedicated workspace that helps minimize distractions. In order to maintain differentiation, employees could plan breaks in which they deal with personal tasks or needs while ensuring that they do not overly switch between work and non-work activities during the workday. Considering the interdependencies between the individual and team levels, teams should take time to discuss and plan their shared availability in order to increase their integration efforts. Consistent with paradox theory, one negative reinforcement loop or vicious cycle is likely to occur as employees increase their autonomy or flexibility when working from home, which leads to misalignments, a lack of responsiveness, and relational costs at the team level.

5.4.3. Reduce Excessive Differentiation at the Team Level

Previous findings highlight the importance of familiarity (Maynard et al., 2019) and cohesion (Chaudhary et al., 2022) for virtual team effectiveness. Although dispersed or virtual team members may build familiarity, it has been noted that the familiarity built between collocated members has a stronger effect on performance (Staats, 2012). As a consequence, meeting at the office and ensuring that all team members have the time to socialize and work together can lower their sense of psychological distance and build social connections (Golden & Raghuram, 2010; Hinds & Cramton, 2014). Even when team members are geographically distributed, they can enhance their sense of psychological proximity through deep, frequent, and synchronous communication (Curșeu, 2006; O’Leary et al., 2014; Wilson et al., 2008). Drawing on the findings from our focus groups, we suggest that team leaders facilitate deep and personal communication in hybrid teams in order to foster social connection and team cohesion, and these interventions would in turn serve to foster individual relational needs.

5.4.4. Foster Integration at the Team Level

We recommend formally adapting organizational and team practices to bridge the spatial and temporal distances of hybrid work through the use of both technology-focused and group-focused interventions. Previous research suggests that team coordination norms and clear systems help reduce uncertainty (Wilson et al., 2008). First, we suggest implementing coordination protocols, such as collaboratively setting communication norms that respect each other’s availability and boundaries. In order to improve team coordination and reduce process losses, team leaders should also clearly define team roles and expectations.