Managing Global Talent: Innovative Solutions and a Sustainable Strategy Using a Human-Centric Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction and Background

1.1. Emerging Challenges in the Talent Management Context

1.2. Global Talent Management Strategies for Navigating Technological, Socio-Economic, and Cultural Megatrends

1.3. Global Talent Management Approaches in Republic of Korea

- Human capital approaches focus mostly on the individual trajectory development of talented employees outside of an organizational context; however, due to recent global trends in talents’ mobility, inclusive talent development should be considered as a key talent management approach for global companies under the influence of external factors.

- The current literature addresses challenges like talent flow, generational differences, and competency shortages; however, there are gaps in the research analysis of systematic human capital approaches which lead firms to sustain a competitive advantage in a volatile global environment.

- The literature review identifies three thematic clusters within global talent management: global work experiences, talent management approaches, and GTM; however, it is necessary to discuss advanced solutions and technologies which help to develop a competitive business strategy within the integration of human-centric approaches.

- What are the crucial factors of the Korean economy and society affecting global talent strategy approaches within a firm?

- What are the motivations and expectations of global talent in Republic of Korea?

- Which innovative strategic solutions could be suggested for effectively motivating global talent within a company to engage in continuous development in Republic of Korea using a human-centric approach?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Scope of Global Talent Management

2.2. Global Talent Management Theories

- The first approach focuses on mechanical characteristics and is an attempt at “rebranding”, which includes already-established terms such as human resource management, personnel selection, selection, and leadership development and succession planning. This approach assumes that TM is a new label for the traditional practice of strategic human resource management (Swailes, 2020).

- The second approach emphasizes the development of “talent reserves”, describing TM similarly to the concept of “Succession Planning”. Talent reserves are conceptualized as a mechanism for maintaining a steady pipeline of capable employees; however, this approach tends to emphasize a singular dimension of strategic talent management, often overlooking other critical parameters such as development, engagement, and retention (Thunnissen & Van Arensbergen, 2015).

- The third approach takes a subjective view of talent, considering people as “talent” rather than “talent” being their “characteristic”. This approach can be further divided into two approaches—exclusive and inclusive:

- (A)

- The exclusive approach assumes that talent is inherent only to certain people and is therefore limited (Samo et al., 2020). This approach emphasizes that talented employees should be given important roles and positions in organizations.

- (B)

- The inclusive approach assumes that all employees are talented, and an organization-wide effort is needed to encourage people to explore and improve their talents by providing opportunities to everyone (Chhabra & Sharma, 2018).

- The fourth approach addresses the rapid development of technologies in the workplace and prioritizes the individual needs, well-being, and experiences of employees, focusing on creating a positive and inclusive work environment that respects cultural differences and empowers individuals regardless of their location (Wiblen et al., 2020; Holland, 2019).

2.3. Perspectives of Global Talent Management Implication

- (1)

- The systematic identification of pivotal positions that differentially contribute to an organization’s sustainable competitive advantage on a global scale;

- (2)

- The development of a talent pool of high-potential and high-performing incumbents who reflect the global scope of the MNE (multinational enterprise) to fill these roles;

- (3)

- The development of a differentiated global HR architecture to fill these roles with the best available incumbents (key competencies and competitive advantages) to ensure their continued commitment to the MNE.

- GTM is not a simple extension of global HR sub-functions, but introduces the term which is used interchangeably with strategy management development tasks.

- GTM is more strategic and focuses on the future needs for employee capabilities and motivation that will meet the future needs and core values of the business.

- GTM is selective and focuses on key positions that are perceived by management as vital to the development of the long-term competitive advantage of any business.

- GTM is a capability-based and capacity-building approach to strategic HR management in global markets.

- GTM is focused on ESG trends and prioritizes the individual needs, well-being, and experiences of employees, focusing on creating a positive and inclusive work environment that respects cultural differences and empowers individuals regardless of their location to lead the sustainable future of enterprises.

2.4. Human-Centric Approach in Global Talent Management Studies

- ✓

- Leaders should place human well-being at the forefront and embrace a “double bottom line” strategy that balances financial success with societal and individual empowerment in the era of artificial intelligence (AI).

- ✓

- AI presents an opportunity to augment human capabilities—enhancing creativity, emotional intelligence, and problem-solving—by taking over repetitive tasks.

- ✓

- To navigate the challenges AI brings, including job displacement, algorithmic bias, and data privacy concerns, collaboration among policymakers, business leaders, and educators is essential.

- ✓

- Effectively incorporating advanced technology requires the creation of new roles where humans and AI collaborate, leveraging their unique strengths to enhance one another.

- ✓

- Instead of perceiving change as a risk, organizations should cultivate a culture of ongoing learning. Comprehensive reskilling and retraining initiatives can prepare individuals with the necessary skills to work alongside AI.

- (1)

- Self-determination theory (SDT) emphasizes intrinsic motivation, autonomy, and competence as crucial for optimal employee engagement and development in strategy formulation (Deci & Ryan, 2000).

- (2)

- Job demands-resources (JD-R) theory highlights the balance between job demands and available resources in promoting employee well-being and organizational performance (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007).

- (3)

- Positive organizational scholarship (POS) underlines the role of fostering positive practices, relationships, and strengths-based development to achieve flourishing organizations (Cameron et al., 2003).

- (4)

- Human capital theory is reinterpreted through a human-centric lens, stressing not only investment in skills and education but also creating supportive ecosystems that nurture human potential (Becker, 1993).

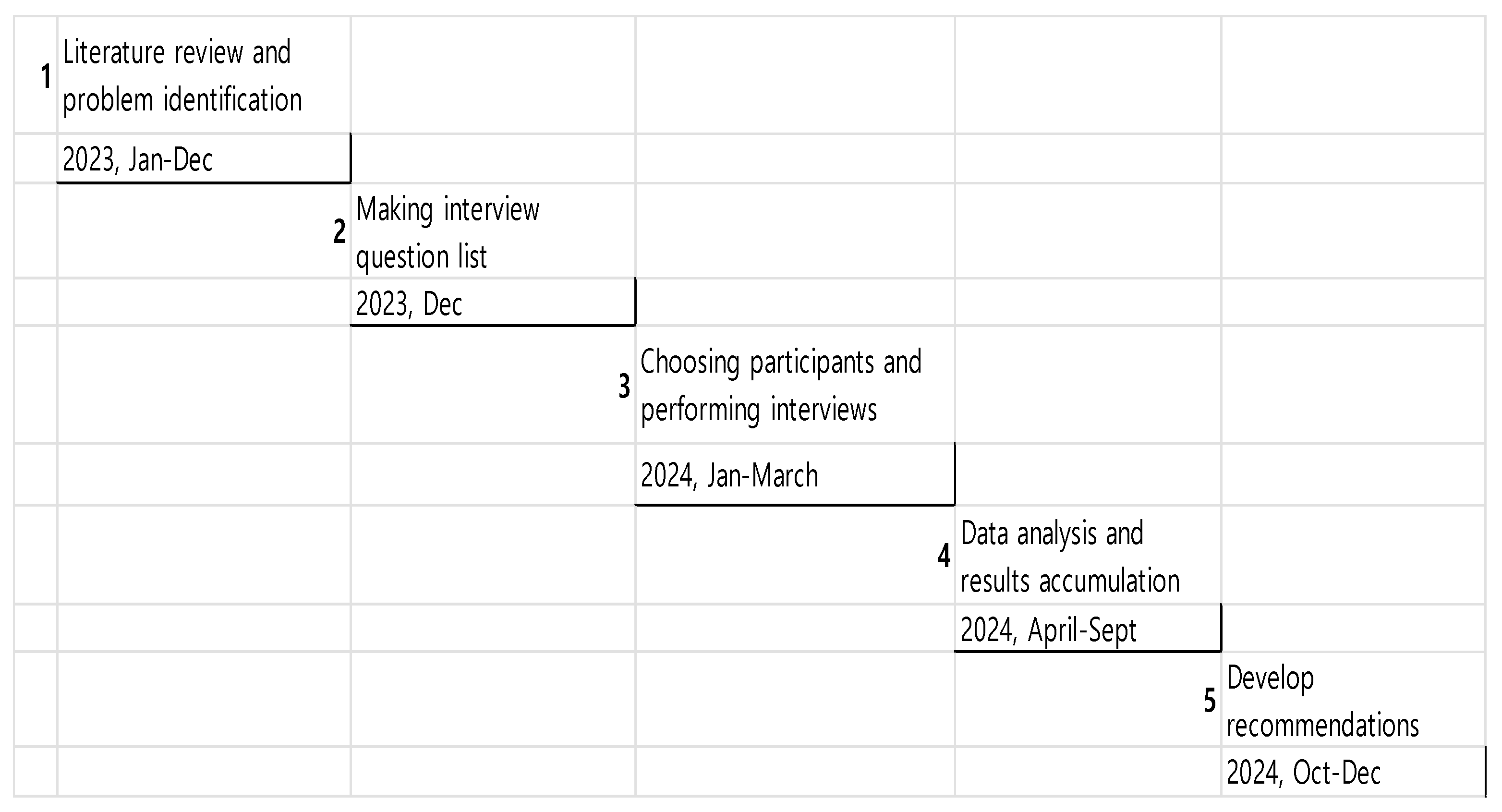

3. Methodology: Global Talent Management Survey—The Case of Republic of Korea

3.1. Participants and Procedures for Data Collection

3.2. Data Analysis

3.2.1. Data Analysis 1: Profile of Global Talent in the Korean Market

3.2.2. Data Analysis 2: Global Talent Motivation Strategies in the Korean Labor Market

- ✓

- General Naturalization (일반귀화);

- ✓

- Simplified Naturalization (간귀화귀화);

- ✓

- Special Naturalization (특별귀화)—the “global talent” track, which allows the individual to hold dual citizenship.

- 1.

- Motivational reasons for foreign global talent to work in Republic of Korea related to the technological megatrend.

- 2.

- Motivational reasons for foreign global talent to work in Republic of Korea related to the socio-economic megatrend.

- 3.

- Motivational reasons for foreign global talent to work in Republic of Korea related to the cultural megatrend.

3.2.3. Data Analysis 3: Global Talent Scarcity Problems in Republic of Korea

- 1.

- Global talent scarcity problems faced by foreign global talent working in Republic of Korea related to the technological megatrend.

- 2.

- Global talent scarcity problems faced by foreign global talents working in Republic of Korea related to the socio-economic megatrend.

- 3.

- Global talent scarcity problems faced by foreign global talent working in Republic of Korea related to the cultural megatrend.

4. Results and Recommendations

- Supporting Talent for the Future

- 1.1.

- Developing basic digital competencies in lifelong centers for the children of global talent;

- 1.2.

- Supporting the identification and development of talent capable of managing the society of the future;

- 1.3.

- Enhancing competencies of higher-education specialists in scientific and engineering fields to effectively respond to future challenges.

- Creating Favorable Conditions for the Career Growth of Young Scientists

- 2.1.

- Developing a research base for young scientists;

- 2.2.

- Strengthening support for increasing the number of young scientists and engineers;

- 2.3.

- Supporting talent in advanced innovative fields (future directions).

- Developing Advanced Skills and Competencies of Scientific and Technical Personnel

- 3.1.

- Providing systematic support for training scientific and technical personnel;

- 3.2.

- Developing digital competencies among scientific and technical personnel;

- 3.3.

- Creating conditions to increase the number of women scientists and engineers;

- 3.4.

- Expanding career growth opportunities for scientific and technical personnel.

- Enhancing Openness and Mobility in the Human Capital Sphere

- 4.1.

- Ensuring the inflow of talented specialists from abroad;

- 4.2.

- Increasing intersectoral mobility of talented specialists;

- 4.3.

- Strengthening ties between science and society;

- 4.4.

- Developing legal foundations and institutional frameworks for science.

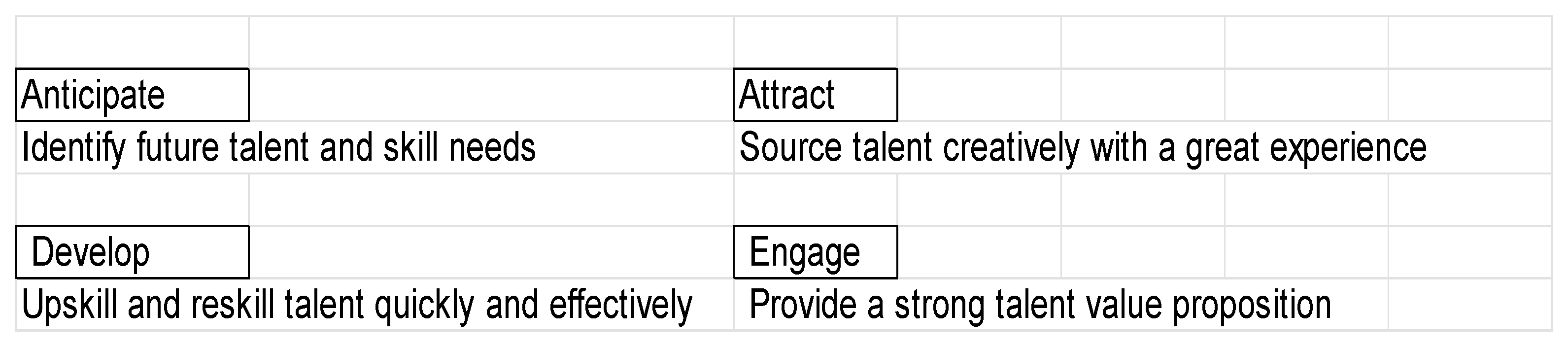

- Anticipate: Create skills-based workforce planning capabilities to better forecast talent needs, understand the skills that workers have today, and determine how to address the gaps.

- Attract: Take an innovative approach to talent and skills by viewing the process through the employee lens and creating a candidate-centric journey enabled by digital technology and AI.

- Develop: Combine the expertise of a world-class faculty with technology to provide the necessary organizational learning programs and comprehensive upskilling solutions to ensure a clear return on investments.

- Engage: Create a global talent value proposition grounded in the company’s purpose, culture, and overall talent and skills strategy.

5. Discussion

- What are the crucial factors of the Korean economy and society affecting the global talent management system of a business? (This question was addressed by collecting technological, socio-economic, and cultural megatrends and statistical data.)

- What are the motivations and expectations of global talent in Republic of Korea? (This question was addressed by analyzing interview results.)

- Which innovative solutions could be suggested for effective global talent motivation to engage in continuous development in Republic of Korea with a human-centric approach? (This question was addressed by proposing a human-centric approach (INSEAD, 2023).)

- ✓

- Creating a meaningful work environment;

- ✓

- Caring for health and safety;

- ✓

- Creating opportunities for growth and unlocking potential;

- ✓

- Forming a comfortable and creative atmosphere;

- ✓

- Prioritizing the happiness and well-being of employees;

- ✓

- Creating values for society;

- ✓

- Developing a friendly culture of communication;

- ✓

- Creating a role model of a human-centric culture.

- “Employees”, internal corporate responsibility, which evaluates the practices of organizations in relation to their personnel;

- “Community”, external corporate responsibility, which evaluates the company’s social policy for society.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WEF | World Economic Forum |

| ILOSTAT | International Labor Organization Statistics |

| GTM | Global talent management |

| IMD | Institute of Management Development |

| HRM | Human resource management |

| MCOT | Multiple Citizenship for Outstanding Talent |

| STEM | Science, technology, engineering, and mathematics |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| Question |

| Age |

| Sex |

| Level of education |

| Family status |

| Primary area of expertise (major, profession) |

| Working area: Business/Academia/Research |

| In which industry do you (your company) operate? |

| Job title |

| Your average wage per year (excluding CEO) (approx.) |

| Period of working/staying in Korea |

| Have obtained global talent status in Korea/abroad? |

Appendix A.2

| Question | “yes”, % of respondents | “no”, % of respondents |

| Have you obtained more the social benefits staying in Korea rather than in your home country? | 62 | 38 |

| Have your social, cultural and professional expectations been satisfied in Korean markets? | 49 | 51 |

| Do you have any problems with using technologies at workplace in Korea? | 32 | 68 |

| Do you suffer from cross-cultural gap? | 78 | 22 |

| Are you satisfied with your Korean language proficiency? | 35 | 65 |

| Do you feel any inconvenience in communication with local citizens/colleagues? | 53 | 47 |

| Have you been satisfied with your career path in Korean organization? | 54 | 46 |

| Have you been promoted at your organization during last 5 years? | 39 | 61 |

| Does your organization provide you all necessary information regarding your job? | 65 | 35 |

| Have you developed your professional skills in Korea? | 67 | 33 |

| Do you regular participate in training programs in Korea? | 25 | 75 |

| Do you belong to any professional community in Korea? | 25 | 75 |

| Does your family satisfy with cultural and social benefits in Korea? | 21 | 79 |

| Have your registered any intellectual property in Korea? If yes, was the application process simple? | 5 | 95 |

| If you doing business in Korea have your business been developed well/fast in Korean market? | 55 | 45 |

| Does your business/project have strong cooperation with local market? | 66 | 44 |

| Do you prefer to apply for international research grants in Korea? | 82 | 18 |

| Do you prefer to apply for local research grants in Korea? | 22 | 78 |

| Does your company/team have strong cooperation with local businesses/communities? | 68 | 32 |

| Is it easy to invest in your start-up/project in Korea? | 52 | 48 |

| Is it easy to manage Korean employees/students? | 75 | 25 |

| Is it easy to be a part of Korean business/employment culture? | 33 | 67 |

| Do you use online technologies every day at your work place? | 95 | 5 |

References

- Alina, M. (2017). Employer branding and talent management in the digital age. Management Dynamics in the Knowledge Economy, 5, 289–306. [Google Scholar]

- Annual Review. (2024). Annual review report. Annual review of organizational psychology and organizational behavior (Vol. 11, pp. 393–421). Available online: https://www.annualreviews.org/content/journals/orgpsych (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The job demands-resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, G. S. (1993). Human capital: A theoretical and empirical analysis, with special reference to education (3rd ed.). University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Boston Consulting Group. (2022). Talent & skills strategy consulting. Available online: https://www.bcg.com/capabilities/people-strategy/talent-skills-strategy (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Boston Consulting Group. (2024). Talent development. Available online: https://www.bcg.com/capabilities/people-strategy/talent-skills-strategy (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Business Korea. (2025). Business Korea report. Available online: https://www.businesskorea.co.kr (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Caligiuri, P. (2000). The big five personality characteristics as predictors of expatriate success. Personnel Psychology, 53, 67–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, K. S., Dutton, J. E., & Quinn, R. E. (2003). Positive organizational scholarship: Foundations of a new discipline. Berrett-Koehler. [Google Scholar]

- Chhabra, N. L., & Sharma, S. (2018). Linking dimensions of employer branding and turnover intentions. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 26, 282–295. [Google Scholar]

- Collings, D. G., & Conroy, K. (2024). Global talent management. In Encyclopedia of international strategic management. Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Collings, D. G., & Mellahi, K. (2009). Strategic talent management: A review and research agenda. Human Resource Management Review, 19, 304–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collings, D. G., Mellahi, K., & Cascio, W. F. (2019). Global talent management and performance in multinational enterprises: A multilevel perspective. Journal of Management, 45(2), 540–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deloitte Report. (2025). Self-assessed preparedness of organizations’ talent worldwide for the adoption of generative artificial intelligence (AI) as of 2024 [Graph]. Statista Publishing. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1451249/preparedness-talent-for-genai-adoption-worldwide/ (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- Docquier, F., Rapoport, H., & Beine, M. (2017). Brain drain and economic growth: Theory and evidence. Journal of Development Economics, 88, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Dragoni, L., Oh, I.-S., Tesluk, P. E., Moore, O. A., VanKatwyk, P., & Hazucha, J. (2014). Developing leaders’ strategic thinking through global work experience: The moderating role of cultural distance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 99, 586–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragoni, L., Oh, I. S., & Vankim, M. (2020). Human-centric business models and global talent management: The role of strategic integration. Journal of Business Research, 109, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- EOS Report. (2023). Hiring in South Korea: Navigating the talent market, EOS. Available online: https://eosglobalexpansion.com/hiring-in-south-korea-talent-market/ (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Evans, P., Rodriguez-Montemayor, E., & Lanvin, B. (2021). Talent competitiveness: A framework for macro talent management. In The Routledge companion to talent management (pp. 109–126). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ewerlin, D. (2013). The influence of global talent management on employer attractiveness: An experimental study. German Journal of Human Resource Management, 27(3), 279–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farndale, E., Scullion, H., & Sparrow, P. (2010). The role of the corporate HR function in global talent management. Journal of World Business, 45, 2161–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraro, F., Yan, S., & Almandoz, J. (2019). The rise of socially responsible investment funds: The paradoxical role of the financial logic. Administrative Science Quarterly, 64, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo-Gallardo, E., Dries, N., & González-Cruz, T. F. (2013). What is the meaning of “talent” in the world of work? Human Resource Management Review, 23, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galma, K., Ruffino, G., & Roulet, T. (2022, June). Four experts on how leaders can best respond to a changing global landscape. World Economic Forum. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/06/young-global-leaders-lead-differently-changing-global-landscape/ (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Garavan, T. N., Morley, M. J., Cross, C., Carbery, R., & Darcy, C. (2021). Tensions in talent: A micro practice perspective on the implementation of high potential talent development programs in multinational corporations. Human Resource Management, 60, 273–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Talent. (2020). Global talent visas report. Available online: https://www.insead.edu/system/files/2023-11/gtci-2023-report.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- Hector, O., & Cameron, R. (2023). Human-centric management: Nurturing talent, building culture, and driving organizational success. International Journal of Science and Society, 5, 511–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, D. (2019). Subjective bias in talent identification: Understanding critical perspectives. In Managing talent (book chapter). Spring Nature. [Google Scholar]

- ILOSTAT. (2018). International Labour Organization. Report. Available online: https://ilostat.ilo.org/data/ (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- INSEAD. (2023). INSEAD report. The global talent competitiveness index, 2023. Available online: https://kccuk.org.uk/media/documents/KCC_Artist_Visa_Legal_Guidance_ENG-KOR.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Islam, S. A. M. (2024). From transactional to transformational: HR as a strategic business partner. International Journal For Multidisciplinary Research, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Kaliannan, M., Darmalinggam, D., Dorasamy, M., & Abraham, M. (2023). Inclusive talent development as a key talent management approach: A systematic literature review. Human Resource Management Review, 33(1), 100–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, S. P., & Kerr, W. R. (2017). Immigrant Entrepreneurship. In J. Haltiwanger, E. Hurst, J. Miranda, & A. Antoinette Scholar (Eds.), Measuring entrepreneurial businesses: Current knowledge and challenges (pp. 187–249). Univeristy of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kerr, W. R. (2016). Global talent flows. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 30, 83–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, S. (2021). Work, employment & society (Vol. 35, pp. 203–220). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Korea. (2025). Korea.net. Available online: http://korea.net/ (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Korea Times. (2025). Available online: https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/nation/2025/02/113_342761.html (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Korean Immigration Service. (2025). Available online: https://www.hikorea.go.kr/info/InfoDatail.pt?CAT_SEQ=278&PARENT_ID=148 (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Linko. (2023). Linko technology report. Available online: https://aquaticinformatics.com/products/fog-pretreatment-regulatory-software/ (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Maurya, K. K., Agarwal, M., & Srivastava, D. K. (2020). Perceived work–life balance and organizational talent management: Mediating role of employer branding. International Journal of Organization Theory & Behavior, 24, 41–59. [Google Scholar]

- Mcdonnell, A., Hickey, C., & Gunnigle, P. (2011). Global talent management: Exploring talent identification in the multinational enterprise. European Journal of International Management, 5, 174–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLennan, M. (2020). ESG as a workforce strategy. Marsh McLennan. Available online: https://www.mmc.com/insights/publications/2020/may/esg-as-a-workforce-strategy.html (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Mendy, J. (2022). Internationalizing HRM framework for SMEs: Transcending high-performance organisation theory’s economic utilitarianism towards humanism. In The international dimension of entrepreneurial decision-making: Cultures, contexts, and behaviours (pp. 137–162). Spinger. [Google Scholar]

- NRF. (2025). National Research Fund of Korea. Available online: https://www.nrf.re.kr/index (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Ortega-Lapiedra, R., Marco-Fondevila, M., Scarpellini, S., & Llena-Macarulla, F. (2019). Measurement of the human capital applied to the business eco-innovation. Sustainability, 11, 3263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H. (2023). The context matters to the exclusive talent management: How to measure and pay in South Korea. Global Business Review. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H., Patel, P., Varma, A., & Jaiswal, A. (2022). The challenges for macro talent management in the mature emerging market of South Korea: A review and research agenda. Thunderbird International Business Review, 64(5), 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patagonia. (2025). Available online: https://www.patagonia.com/home/ (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- PwC Report. (2025). Workforce of the future: The competing forces shaping 2030. Available online: www.pwc.com/people (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Reis, I., Sousa, M. J., & Dionísio, A. (2021). Employer branding as a talent management tool: A systematic literature revision. Sustainability, 13(19), 10698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salesforce. (2025). Available online: https://www.salesforce.com/ap/?ir=1 (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Samo, A. S., Talreja, S., Bhatti, A. A., Asad, S. A., & Hussain, L. (2020). Branding Yields Better Harvest: Explaining the Mediating Role of Employee Engagement in Employer Branding and Organizational Outcomes. Etikonomi: Jurnal Ekonomi, 19, 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuler, R. S., Jackson, S. E., & Tarique, I. (2011). Global talent management and global talent challenges: Strategic opportunities for IHRM. Journal of World Business, 46(4), 506–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scullion, H., Collings, D., & Caligiuri, P. (2010). Global talent management (global HRM). Journal of World Business, 45, 105–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, G.-W., & Choi, J. (2015). Global talent: Skilled labor as social capital in Korea (pp. 23–56). Studies of the Walter H. Shorenstein Asia-Pacific Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, G.-W., Choi, J., & Rennie, M. (2019). Skilled Migrants as Human and Social Capital in Korea. Asian Survey, 59, 673–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shvetsova, O. (2022a). Gig economy: Trends and perspectives. How to define advantages and disadvantages of the gig economy? In Sustainability in the gig economy: Perspectives, challenges, and opportunities in Industry 4.0 (pp. 19–31). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Shvetsova, O. (2022b). Transformation of university teaching methods in South Korea: Crisis and new sustainable forms of the education process. In Digital teaching and learning in higher education: Developing and disseminating skills for blended learning (pp. 165–188). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Sousa, B., Ferreira, J. J., Jayantilal, S., & Dabic, M. (2024). Global talent management–talents, mobility and global experiences–a systematic literature review. Journal of Global Mobility, 12(3), 444–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. (2023). Global talent competitiveness index. Statista report 2023. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1039195/global-talent-competitiveness-index-leading-countries/ (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Statista. (2025). Equinix. (survey of June 28, 2022). How much of a threat do you consider a shortage of IT talent to be to your organization? [Graph]. Statista Publishing. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1337541/threat-shortage-it-talent-organizations-worldwide-by-region/ (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- Stip Compass. (2023). Sejong science fellowship program. Available online: https://stip.oecd.org/stip/interactive-dashboards/policy-initiatives/2023%2Fdata%2FpolicyInitiatives%2F99991401 (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Swailes, S. (2020). Responsible talent management: Towards guiding principles. Journal of Organizational Effectiveness: People and Performance, 7(2), 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swailes, S., & Lever, J. (2022). Becoming and staying talented: A figuration analysis of organization, power and control. Ephemera, 23(2), 61–84. [Google Scholar]

- Tansley, C., & Kirk, S. (2018). You’ve been framed-framing talent mobility in emerging markets: ‘You’ve been framed’. Thunderbird International Business Review, 60, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarique, I., & Schuler, R. (2010). Global talent management: Literature review, integrative framework, and suggestions for further research. Journal of World Business, 45, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thunnissen, M., & Van Arensbergen, P. (2015). A multi-dimensional approach to talent: An empirical analysis of the definition of talent in Dutch academia. Personnel Review, 44(2), 182–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, R. L. (2016). New perspectives on human resource management in a global context. Journal of World Business, 51, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyskbo, D. (2025). Beyond performance and potential in talent management: Exploring the impact of mobility on talent designation. Personnel Review, 54, 1081–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WEF. (2018). WEF report, future of jobs. World Economic Forum. Available online: https://www3.weforum.org/ (accessed on 11 January 2025).

- Wernerfelt, B. (1984). A Resource-based view of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 5, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiblen, S., Dery, K., & Grant, D. (2020). Talent management in the era of digital transformation: Toward a human-centric approach. Journal of Business Research, 124, 588–599. [Google Scholar]

- Wiblen, S., & McDonnell, A. (2020). Connecting ‘talent’ meanings and multi-level context: A discursive approach. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 31(4), 474–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WISET. (2024). Korea Foundation for women in science, engineering and technology. Available online: https://www.wiset.or.kr/ (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- World Economic Report. (2025). World economic forum annual meeting. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/meetings/world-economic-forum-annual-meeting-2025/ (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Würtenberger, F. (2023). Pivoting to a Web3 product and building a healthy remote culture with human-centric leadership. In Change management revisited: A practitioner‘s guide to implementing digital solutions (pp. 91–102). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Yusof, R., Azizan, S., & Osman, N. S. (2024). HR analytic and human centric approach: Challenges and direction towards HR insights. Global Business and Management Research: An International Journal, 16(4), 1275–1282. [Google Scholar]

| Global Talent Labor Market: Megatrend 1 | Global Talent Labor Market: Megatrend 2 | Global Talent Labor Market: Megatrend 3 |

|---|---|---|

| Technological: the automation and development of technological innovations | Socio-economic: changes in the demographic composition of the population and the balance of power in geopolitics and economics | Cultural: the changing values and culture of the working population |

| Problems in motivating global talent to engage in continuous development: the automation of routine tasks, the emergence of new and the disappearance or complication of certain old types of activities, and increased requirements for employee qualifications and increased productivity | Problems in motivating global talent to engage in continuous development: old approaches to organizing workplaces and pension and social insurance systems; the need for environments conducive to the effective implementation of their potential | Problems in motivating global talent to engage in continuous development: a lack of favorable environments for diversity and inclusion and mobility opportunities |

| Strategy of enterprises: continuous learning and upskilling, create dynamic career pathways for emerging roles, leverage technology to personalize employee development | Strategy of enterprises: redesign workplace models with flexibility and phased retirement, modernize benefits and social systems, create inclusive leadership and career development programs | Strategy of enterprises: strong culture of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI), prioritize cross-border mobility programs, promote values-driven leadership aligned with employees’ social and personal values |

| Approaches | Key Point | References |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Rebranding | TM is a new label for the traditional practice of human resource management | Alina (2017); Reis et al. (2021) Samo et al. (2020) |

| 2. Talent reserves | Talent reserves are viewed as a mechanism that ensures a regular supply of capable employees for strategic decisions | Mcdonnell et al. (2011) Schuler et al. (2011) |

| 3. Subjective approach (a) Exclusive (b) Inclusive | (a) Talented employees should be given important roles and positions in organizations (b) Organizations should encourage people to explore and improve their talents by providing opportunities to everyone with focus on key strategic competencies | Kaliannan et al. (2023) Holland (2019) Annual Review (2024) Collings et al. (2019) |

| 4. Human-centric approach | This approach prioritizes the individual needs, well-being, and experiences of employees, focusing on creating a positive and inclusive work environment that respects cultural differences and empowers individuals regardless of their location for sustainable valued strategic organization | Hector and Cameron (2023) Mendy (2022) Würtenberger (2023) Yusof et al. (2024) Thunnissen and Van Arensbergen (2015) |

| Theory | Key Point | References |

|---|---|---|

| Strategic Talent Management | Focus is on systematically developing talent pools and differentiated HR architectures to support strategic business goals globally | Collings and Mellahi (2009) |

| Resource-based theory | Talented employees are seen as valuable, rare, inimitable, and non-substitutable resources that provide competitive advantage | Ortega-Lapiedra et al. (2019); Wernerfelt (1984); Barney (1991) |

| Global talent theory | Multinational enterprises (MNEs) manage the flow of talent across geographic borders, developing global staffing strategies | W. R. Kerr (2016); Docquier et al. (2017); Tung (2016) |

| ESG-Driven Talent Management (based on human-centric approach) | Importance of employee well-being, diversity, inclusion, and ethical practices with prioritization of both organizational performance and societal impact | Wiblen et al. (2020); McLennan (2020); Ferraro et al. (2019) |

| Characteristic | Data |

|---|---|

| Age | 30–55 |

| Sex | Male (75%), female (25%) |

| Level of education | 100% PhD |

| Family status | Single (65%), married (25%), married with kids (10%) |

| Primary area of expertise | STEM |

| Business/Academia/Research | 15%/35%/50% |

| Industries | Automotive (5%), chemicals, physics (35%), semiconductors, IT (60%) |

| Average wage per year (excluding CEO) | USD 100,000–170,000 |

| Period of working in Korea | 5–10 years (65%), more than 10 years (35%) |

| Job title | Researcher (55%), professor (25%), manager (including CEO) (20%) |

| Obtained global talent status in Korea/abroad * | In Korea (75%), abroad (25%) |

| Megatrend (External Factor) | Global Talent Management Issues (Internal Factors) | |

|---|---|---|

| Motivational Drivers (Positive Issues) | Structural Barriers (Negative Issues) | |

| Technological | Excellent technological infrastructure, equipment, and IT and good opportunities to establish a research lab or apply for intellectual rights | Restricted access to local innovations and inventions; a lack of international professional communities in the field of STEM, a lack of international conferences, difficulties transferring innovations abroad, and no interest in open innovation |

| Socio-economic | High interest from Korean organizations in foreigners’ experience and knowledge, competitive average wage, easy to start conducting business, possible research cooperation with local research teams, and business support for legal and financial schemes | High living costs (including rental costs and children’s educational fees), a lack of opportunities for career growth, self-promotional difficulties (for example, most educational programs and professional training sessions are held only in the Korean language), and a period of hard work without breaks for a good pension scheme |

| Cultural | High interest from Korean society in foreigners and different socio-cultural programs for foreigners | Language barriers, huge cross-cultural gaps, and a lifelong “status of foreigner” |

| Area of Improvement | Current Government Strategy (Fifth Basic Plan Tasks) | Enterprise-Level Recommendations (Human-Centric Approach) |

|---|---|---|

| Supporting Talent for the Future |

| Develop AI tools with English language support for self-development and online/metaverse platforms for professional training; establish an online platform with feedback opportunities for foreigners in Korea |

| Creating Favorable Conditions for the Career Growth of Young Global Talent Scientists |

| Establish a strong international community (association) for foreign global talent in the Korean market; hold annual global talent conference, change the local rules of career path, and make the promotional route available in Korean technological companies |

| Developing Advanced Skills and Competencies of Scientific and Technical Personnel |

| Provide more mobility and flexible working conditions for women in STEM areas; establish motivational awards, workshops, and competitions among global talent women in the Korean market; create a separate database for intellectual property rights and invention solutions for foreigners |

| Enhancing Openness and Mobility in the Human Capital Sphere |

| Create additional routes for global talent to build their career and professional path within intersectoral mobility, arrange an effective system of work and life balance (changes in labor contract and pension schemes) |

| Stakeholder | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| Government Agencies |

|

| Universities and Research Institutions |

|

| Private Enterprises |

|

| Civil Society and Professional Networks |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shvetsova, O. Managing Global Talent: Innovative Solutions and a Sustainable Strategy Using a Human-Centric Approach. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 190. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15050190

Shvetsova O. Managing Global Talent: Innovative Solutions and a Sustainable Strategy Using a Human-Centric Approach. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(5):190. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15050190

Chicago/Turabian StyleShvetsova, Olga. 2025. "Managing Global Talent: Innovative Solutions and a Sustainable Strategy Using a Human-Centric Approach" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 5: 190. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15050190

APA StyleShvetsova, O. (2025). Managing Global Talent: Innovative Solutions and a Sustainable Strategy Using a Human-Centric Approach. Administrative Sciences, 15(5), 190. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15050190