Abstract

Tourism has become one of the most important industries in the business world, significantly impacting various economies. In order to have a better understanding of tourist behavior, this study aims to examine the image of the destination and the value of the brand as predictors of the behavior of tourists, assuming happiness as a mediating link. From a quantitative, non-experimental and cross-sectional methodological perspective, the information of a sample of 425 tourists was analyzed. The results support that tourist happiness predicts their intention to revisit a tourist destination (Path Coefficient 0.921). Also, tourist happiness and the intention to revisit predict the intention to recommend a tourist place. These results suggest that tourist happiness plays a fundamental role in aspects such as loyalty and the promotion of a destination, so it is important for tourism companies to promote tourist happiness as a marketing strategy that drives them to word-of-mouth recommendations and the intention to revisit a tourist destination.

1. Introduction

Tourism has become one of the most important industries on the planet, significantly impacting various economies (Godovykh et al., 2023; C.-C. Lee et al., 2021; S.-H. Liang & Lai, 2023). An example of this is the increase in competition between destinations, the development of tourism strategies (Todd et al., 2017) and the sustainable economic growth of many countries (Manhas et al., 2016). Given this trend, it is important to predict tourist behavior, taking as a reference the development of the destination brand as an essential practice to build positive emotional bonds (Ampountolas, 2019).

In the dynamics of a tourist, their behavior and the value of the brand, the image of the destination also emerges, considered as a determining factor in the intentions to recommend or revisit a place; this is structured from the perceptions, beliefs and emotions that tourists have of a tourist destination (Chang, 2021; Dam & Dam, 2021). All of this becomes a mental structure that is influenced by a variety of factors, such as personal experience, promotional campaigns, media and the environment, and plays an important role in tourist behavior, specifically in recommending and revisiting a tourist place (Fayzullaev et al., 2021). Thus, it is stated that a favorable image has the ability to increase interest and attraction towards a destination, while an unfavorable or negative image could disconnect and scare away tourists (Cuesta-Valiño et al., 2022).

A favorable image gives rise to brand value, whose attributes can be tangible and intangible, and this differentiates a tourist destination from the competition, generating happiness and preference in tourists (Bose et al., 2022). According to recent studies, brand value is built through a good image, positive experiences with the brand, quality service and, of course, an effective promotional campaign (J. Lee & Park, 2022; Tran et al., 2021), as it has been proven that a strong brand will not only attract tourists but will also allow economic benefits and a good reputation for the local community (Bose et al., 2022).

Regarding happiness, it is considered as a memorable tourist experience that generates a significant attachment and drives tourists to revisit a tourist destination (Peng et al., 2023); in this sense, promoting happiness is a viable alternative to obtain adequate tourist behavior (Gong & Yi, 2018), being this at the same time a very important variable, since it is known that in the era of happiness 2.0, there is a change of approaches, where the need to satisfy an immediate pleasure currently consists of covering a need for self-realization (Zhang et al., 2024).

According to previous studies, loyal tourists become protagonists when the aim is to achieve stable economic benefits, and their behavior is clear evidence of the effectiveness of marketing, which promotes the increase in popularity and expands the potential market for tourist destinations (Primananda et al., 2022); in this context, it is necessary that tourists maintain a positive perception of the tourist destination, since reputation, previous experience, prestige and/or recognition are fundamental in their behavior and their decision to revisit a place (Tang et al., 2022). Although it is known that people’s behavior changes over time and is transformed according to various factors, it is necessary to keep in mind that one of the determinants of tourist behavior lies in the image of the destination; this means that the more positive and attractive the perception of a tourist destination is, the more positive a tourist’s behavior will also be, boosting this association, the level of satisfaction and the happiness of the tourist (López-Sanz et al., 2021).

Recent precedents explain that in the framework of the Sustainable Development Goals, digital platforms have become a mechanism that contributes to sustainable tourism, and they have seen an upward trend in use due to their ability to connect travelers with service options such as accommodations, transportation and activities that prioritize sustainability (Lacárcel, 2025). In this context, Pinho and Leal (2024) report that just as the objectives of sustainable development are based on economic, ecological and social pillars, sustainable tourism also focuses on these key points, guaranteeing and maximizing the balance between income, environmental preservation and community well-being (Mohanan, 2024). Evidence of sustainable tourism is found in activities such as bicycle tourism, which aims to reduce air pollution, as well as hiking, trekking and others that reduce environmental impacts (Satrya et al., 2024; Senese et al., 2025). This fact represents evidence about tourist practices and intentions of tourists that align the principles of sustainability in their life; thus, it is stated that knowing tourist behavior is fundamental to understanding, in a first overview, the dynamics of the destination image, brand value and happiness regarding tourist behavior.

Based on the above, it is of interest to investigate the influence that destination image and brand value have on tourist happiness and their intention to revisit and recommend a specific destination. There is literature that establishes the influence of brand image and personality (Cruz-Tarrillo et al., 2023), brand value and satisfaction (Tran et al., 2021), image of the destination and the intention to visit (S.-H. Liang & Lai, 2023), and there is even scarce literature that addresses happiness together with tourism experiences, but in a metaverse scenario (Wang & Guo, 2025), while other antecedents focus on measuring or identifying behavior together with satisfaction (Bagheri et al., 2024), which leads to identifying a knowledge gap regarding the role that happiness could assume. However, no studies have been identified that address the role of happiness in the association of destination image and brand value with tourist behavior, even more so in a place like the Peruvian Jungle, characterized by its biodiversity with unique tourist attractions such as lagoons, waterfalls, hot springs and beautiful nature that beautify the tour and awaken in tourists a feeling of happiness due to the direct connection with nature. Despite its beauty, it faces challenges that hinder sustainable tourism development, which requires urgent attention for its preservation and the development of local communities.

Under this premise, this research aims to fill this gap in knowledge by posing the following research objective: to analyze the influence of destination image and brand value on tourist happiness and its impact on the intention to revisit and recommend tourist destinations. To this end, a quick literature review and data collection were conducted, which allowed obtaining results that helped to identify the factors that influence the intention to revisit and recommend a tourist destination. This study focused on tourist destinations in the Peruvian jungle, a geographical area characterized by its natural wealth and a world to discover but with particular needs in terms of tourism promotion. This study allowed us to explore the perceptions of local, regional, national and foreign tourists that will undoubtedly allow the development of effective strategies to improve tourist attractiveness and competitiveness.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Destination Image

Destination image refers to the perceptions, beliefs, impressions and emotions that tourists have about a specific tourist destination (Marques et al., 2021). It is a mental representation that is formed through the tourist’s previous experience, the information received from friends, family, the media and advertising, and other external and internal factors, also known as affective and cognitive image (Akgün et al., 2020). Destination image plays a key role in tourists’ decisions to visit a destination or not, as well as in their behavior while there (Nunes et al., 2020). This can be characterized by several components, such as natural beauty, culture, history, gastronomy, security, hospitality, infrastructure and tourist services, among others (Tang et al., 2022). These components can influence different aspects of the tourist experience, such as satisfaction, intention to revisit and intention to recommend the destination to others (W.-C. Chan et al., 2022).

2.2. Brand Value

Destination brand value refers to the perception and valuation that consumers have about a particular tourist destination (Tasci, 2020). It is a concept that has become increasingly important in the tourism industry due to the growing competition between tourist destinations and the need to stand out among them; it is a combination of the image of the destination and the tourist experience (A. Chan et al., 2021). While image is the general perception that tourists have of a destination, tourist experience refers to the personal interactions and emotions that tourists experience during their stay at the destination. Both aspects are important in determining the value of the brand.

It can be measured through different approaches, including quality perception, loyalty and satisfaction, and can influence the way tourists perceive the value of the destination brand and their decision to revisit or recommend the destination to others. However, theory indicates that androgynous brands generate greater brand value compared to brands that direct their strategies exclusively to the female or male gender (Lieven & Hildebrand, 2016).

2.3. Tourist Happiness

It is undeniable that for a client (tourist) to be happy, the service they received during their stay at a tourist destination must have exceeded their expectations. Making a conceptual approximation, it can be said that this refers to the positive emotional state that a person experiences when traveling and exploring new cultures, places and experiences (Bimonte & Faralla, 2012). This happiness can be caused by various factors, such as personal satisfaction, enjoyment of leisure activities, relaxation and escape from daily routine and learning and discovery, among others (Bimonte & Faralla, 2015). In general, tourist happiness is associated with a feeling of well-being and personal satisfaction that is obtained when traveling (F. Li et al., 2023).

One of the main factors that influence tourist happiness is the quality of the tourist services offered at the destination. This includes the quality of accommodations, the range of leisure activities and experiences and the accessibility and safety of the destination, among other aspects (Gholipour et al., 2022). Tourists tend to feel happier and more satisfied when tourism services meet their expectations and provide them with a memorable and enjoyable travel experience (C.-J. Chen & Li, 2020; Vittersø et al., 2017).

2.4. Intention to Revisit and Recommend

The intention to revisit and recommend tourist destinations is known as the behavior of tourists after having gone through an experience. In addition, it is a key indicator of a destination’s success in the tourism industry. This intention refers to the willingness of tourists to return to a destination and recommend it to others after having had a positive experience (Heydari Fard et al., 2021).

The intention to revisit and recommend a destination is influenced by several factors, one of the most important being the quality of tourist services and the general satisfaction of tourists, which translates into happiness (Mimaki et al., 2022). When tourists have a positive experience at a destination and are happy with the tourism services offered, they are more likely to intend to revisit the destination in the future and recommend it to others (Kaur & Kaur, 2020).

2.5. Hypothesis Development

Some studies have shown that destination image can have a significant impact on brand value. For example, a study conducted by Jawahar and Muhammed (2022) on tourist destinations in India found that a positive image of the destination increased brand value, thus generating tourist loyalty. Meanwhile, A. Chan et al. (2021) argues that, in tourist destinations, the image of the destination has a direct influence on the value of the brand, which affects the intention of tourists to visit and recommend the destination. Based on this idea, it is important to measure the congruence between the projected and received images of the attractions of a destination, since it is known that the value of the brand has the capacity to influence the image of a destination (Y. Li et al., 2023; Tasci, 2020).

In addition, the study conducted by Chi and Pham (2022) sheds light on the role of destination image in strengthening traveler motivational effects. The study provides a framework for segmenting promotional materials associated with destination image based on different types of customers’ internal travel motivations. The framework includes four dimensions: (1) destination image reflecting facilitators of emotion, (2) destination image reflecting facilitators of escaping from the routine of daily life, (3) destination image reflecting facilitators of knowledge seeking and (4) destination image reflecting facilitators of personal development.

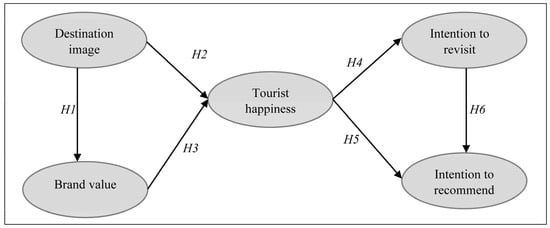

H1:

Destination image influences the brand value of tourist destinations.

H2:

The image of the tourist destination influences the happiness of the tourist.

In addition, Peng et al. (2023) conducted a study investigating the influence mechanism of tourists’ happiness on revisit intention to traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) cultural tourism destinations, and the results showed that tourists’ happiness fosters memorable tourism experiences and place attachment, which in turn stimulates revisit intention. This act is further consolidated when tourists maintain a high health consciousness, and this acts as a significant moderator between happiness, place attachment and revisit intention.

Likewise, Luvsandavaajav et al. (2022) argued that tourist destinations often compete through their image in the minds of potential tourists. Therefore, the image of a destination is critical due to its influence on tourists’ decision making and destination selection; thus, positive changes in the cognitive and affective image of the destination over a given period of time affect a tourist’s motivation to learn and be entertained, as well as influencing tourist satisfaction and revisit intentions (Rodrigues et al., 2023; Tang et al., 2022).

Based on this background, the following hypotheses are raised:

H3:

Brand value influences tourist happiness.

H4:

Tourist happiness influences the intention to revisit a tourist destination.

H5:

Tourist happiness influences the intention to recommend a tourist destination.

On the other hand, when exploring the intention to recommend a tourist destination, the scientific literature establishes that although every destination is a space that seeks to attract the attention of tourists, it has been shown that the hospitality and kindness of residents support the intention to revisit a place and then recommend it (Woyo & Slabbert, 2023). And even the background establishes that when the destination’s resources are limited, visitors or tourists, after having a pleasant experience, feel the intention to visit the destination again and may even recommend the place, thus achieving an increase in the number of visitors (Anton et al., 2021). Based on this, the following hypothesis is raised:

H6:

The intention to revisit influences the intention to recommend a tourist destination.

Figure 1 illustrates a conceptual model of an explanatory nature that articulates the previously developed hypotheses between the constructs in the field of tourist behaviour.

Figure 1.

Theoretical model of this research.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

This research was developed from a non-experimental quantitative transversal methodological perspective (Cruz-Tarrillo et al., 2023). The data collected from tourists were analyzed in their natural state without manipulating any variables. In addition, to measure the causality between the constructs, it was necessary to use the technique of structural equations.

3.2. Instruments

In total, four instruments were used in this research. To measure the image of the tourist destination, the IMATUR scale was used. Moraga et al. (2012) validated to the Peruvian context by Cruz-Tarrillo et al. (2023). This validation process involved adapting the original scale to capture the unique characteristics and attributes of tourism destinations in the Peruvian rainforest, composed of 33 items grouped into five dimensions. The scales of intention to revisit and recommend were also validated, both of which are unidimensional and composed of three items. In addition, the tourist happiness scale was used, composed of 19 items grouped into 4 dimensions (Peng et al., 2023). Likewise, the brand value scale was used, composed of 17 items grouped into four dimensions. The measurement was conducted using a seven-point Likert-type scale, designed to accurately capture respondents’ perceptions and opinions. On this scale, a value of 1 corresponds to strongly disagree, while a value of 7 represents strongly agree. Prior to data collection, a content validation was carried out by five tourism marketing experts, where they evaluated the clarity, congruence and relevance of the items; then, a pilot test was conducted to test the internal consistency of the instruments in the specific context of tourism in the Peruvian jungle. It was applied to a sample of 50 tourists, selected non-probabilistically by convenience. The results indicated high levels of reliability for each instrument (α > 0.70), and no significant problems in item comprehension were identified.

It should be noted that prior to the application of the surveys, authorization was requested from the ethics committee of the Universidad Peruana Unión in order to guarantee the non-existence of any risk or harm to the study participants. After receiving the approval of the aforementioned committee by means of certificate N° 2023-CE-EPG-00181, dated 28 December 2023, the questions were inserted in a Google form, which was divided into three sections: The first was the informed consent, where each participant accepted their participation and authorized the treatment of information anonymously; the second was made up of each of the items that measure the study variables. The third section included the demographic data in order to better understand the profile of the participants.

3.3. Sampling and Data Collection

For the selection of one of the sample units (tourists), this study uses the non-probabilistic technique for convenience. Although it is true that there are several methodological orientations in the literature, this technique is widely used in research (Ragb et al., 2020) due to the ability to provide data when researchers have limited time and scarce economic resources and is efficient in the logistical aspect. The sample consisted of foreign, national, regional and local tourists who have frequented the tourist destinations of Laguna Azul, Cataratas de Ahuashiyacu, located in the district of Sauce in the province of San Martin. In addition, tourists who visited the destination of the thermal baths located in the province of Moyobamba and Tioyacu located in the province of Rioja, all in the San Martin Region, Perú, were included. The data collection was carried out through online surveys, distributed in strategic points such as airports, travel agencies, tourist places and restaurants using WhatsApp as the main tool. All this was possible because one member of the research team works in a travel agency and had the necessary knowledge and strategy for its application of the instrument. A total of 1435 surveys were sent to tourists who had visited some of the destinations between July and November 2023, obtaining a response rate of 30%, or 427 surveys. One respondent who claimed to be a minor (<18 years old) and one respondent who did not complete all questionnaires were excluded from the study; 425 data were submitted for analysis.

3.4. Data Analysis

The data analysis consisted of two phases. In the first phase, the collected data were cleaned, eliminating two cases that were considered atypical data. Basic statistics such as averages, standard deviation, reliability and correlations were used, using SPSS V27. The second phase consisted of statistically evaluating the proposed theoretical model. To achieve this, it was necessary to apply the structural equation model (SEM) using AMOS v25 and JAMOVI as tools. This technique was used because of its ability to analyze complex relationships between latent and observed variables. An adequate sample size was ensured, and multivariate normality was verified using the Mardia coefficient. Linearity and the absence of multicollinearity were also evaluated, determining that the relationships between independent variables did not exceed critical levels. In addition, the model was theoretically justified by determining that the proposed relationships had empirical support (Collier, 2020). The assumptions were tested using the maximum likelihood method to assess the consistency of the model (Byrne & Byrne, 2013; Hair et al., 2020); then, structural estimates were made between the constructs to determine and verify the hypotheses proposed in the research.

4. Results

4.1. Sample Characterization

The data analyzed provided a detailed view of the demographic profiles and behavioral characteristics of tourists. These results are of particular relevance for understanding the dynamics of tourism and its socio-economic implications.

Regarding gender, there was a balanced distribution between men and women (48.5; 51.5). In addition, a high level of education was noted, since the great majority of respondents indicated that they have completed their university studies. Regarding employment status, the data reflect diversity, with a considerable proportion of dependent workers and a significant number of independent workers.

On the other hand, interesting profiles of tourists were detected, taking as variables the origin, duration of the trip and daily expenditure. Table 1 shows an interesting segment made up of local and regional tourists, which suggests a strong potential for domestic tourism. In addition, in relation to duration, there is an interesting proportion that chooses to have short stays (<3 days) due to the factors of time availability and proximity to tourist destinations. On the other hand, with respect to expenditure, the table shows that most tourists spend less than USD 27 a day and generally travel accompanied by their family and/or friends.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic distribution of participants (N = 425).

On the other hand, Table 2 shows the evaluation of different constructs used in the research. All scales have very high internal consistency coefficients (Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega) ranging from 0.979 to 0.993. These values determine the reliability of the constructs. In addition, the correlations between the different variables provide an interesting value due to the high indices found. Significant and positive correlations are observed between the image of the tourist destination and the brand value (r = 0.870), as well as between the happiness of the tourist and the image of the tourist destination (r = 0.852) and the brand value (r = 0.901). These correlations suggest that the constructs are consistently related. In addition, the correlations between the intention to revisit and recommend with the image of the tourist destination, the brand value and the happiness of the tourist are between r = 0.789 and 0.900. The results suggest that a positive image of the tourist destination and high perceived brand equity are associated with greater tourist happiness, which in turn influences tourists’ intention to revisit and recommend the destination.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics, reliability and correlations.

4.2. Theoretical Model Analysis

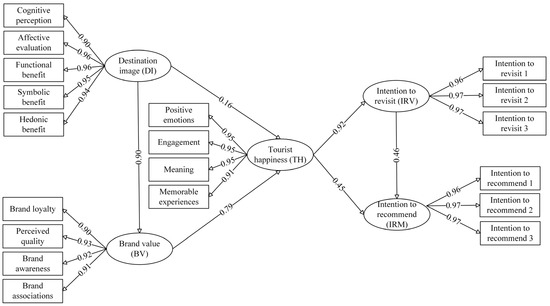

According to the analysis of the model shown in Figure 2, the fit measures reveal an adequate agreement between the proposed theoretical model and the data obtained from the research. In principle, the chi square statistic (464.903) between the degrees of freedom (146) turned out to be within the allowed criteria (X2/df = 3.184). In addition, the significance was less than 0.05 (p value = 0.000 < 0.05). In order to comprehensively evaluate the model fit, the following measures and their corresponding values were considered: the GFI value is 0.894 and the AGFI is 0.863, and both values exceed the threshold of 0.80. On the other hand, the RMSEA is 0.072, the NFI is 0.968, the RFI is 0.962, the CFI is 0.977, the TLI is 0.974 and the IFI is 0.978; as observed, all measures exceed the threshold of 0.90. The fit measures indicate an adequate model consistent with the observed data, as shown in Table 3.

Figure 2.

Confirmatory research model. Source: own elaboration.

Table 3.

Model fit measures criteria.

4.3. Testing the Hypotheses

The hypothesis test revealed significant results that support the causal relationships between the variables studied, as shown in Table 4. Regarding the first hypothesis (H1), a coefficient of β = 0.899 (p < 0.001) was obtained, indicating a significant and positive influence between the image of the tourist destination and the value of the brand. In addition, for the second hypothesis (H2), a coefficient β = 0.161y (p = 0.003) was obtained, indicating that the image of the tourist destination contributes positively to the happiness of the tourist; however, its influence may be more limited than in the previous variable.

Table 4.

Testing research hypotheses.

On the other hand, the third hypothesis (H3) presents a high coefficient β = 0.792 (p < 0.001), indicating a strong causal relationship between brand value and tourist happiness. The fourth hypothesis (H4) also presents a high causal relationship, with β = 0.921 (p < 0.001), indicating a positive and highly significant causal relationship between tourist happiness and the intention to revisit the tourist destination. The fifth hypothesis (H5) was also accepted because β = 0.451 (p < 0.001) was observed, indicating that tourist happiness positively influences the intention to recommend the tourist destination.

Finally, the sixth hypothesis (H6) was accepted with β = 0.464 (p < 0.001), indicating a positive and significant relationship between the intention to revisit the tourist destination and the intention to recommend it. This indicates that tourists who plan to return to the destination are also more likely to recommend it to other people.

5. Discussions and Conclusions

Based on the results, this research expands the literature by including tourist happiness, brand value and destination image as predictors of intentions to return and recommend tourist destinations. From the perspective of tourist behavior (intention to visit and recommend), this research represents a deepening of the theory; specifically, this study contributes to a better understanding of tourists’ intentions to return to the destination and at the same time recommend it.

This study has shown that the image of the destination maintains a special link with the value of the brand because a strong causal relationship was found, β = 0.899; this means that a good or favorable image of the tourist destination is highly associated with a positive perception of the brand value. These findings support the theory that the image of a destination plays an important role in the formation of brand perceptions (S.-H. Liang & Lai, 2023). Furthermore, when tourists have a positive image of a destination, they are more likely to perceive a related brand as loyal, a quality brand, which can influence future travel decisions even in times of economic recession when tourism activity suffers significantly (Majeed et al., 2024).

It was also shown that the image of the tourist destination has a causal relationship with the happiness of the tourist. To support these findings, previous studies indicate that when tourists have memorable experiences in tourist places, they feel excited, pleasant and happy during their stay (X. Chen et al., 2023; Xiao et al., 2022). In this context, when tourists acquire a positive image of a tourist destination, they feel a strong motivation that drives them to enjoy the moment, since uncertainty disappears and they concentrate on investing their time in enjoying their stay at the selected destination (Galiano-Coronil et al., 2023).

Furthermore, this study has shown that brand value allows for cultivating loyalty towards a tourist destination, since the destination has exceeded the tourist’s expectations, so aspects such as physical facilities, quality of services, customer service and adequate infrastructure play a crucial role in generating happiness in the tourist (Huang et al., 2021). Therefore, it is important that tourism professionals allow positive opinions that build a positive brand value that remains in the minds of tourists as a memory of positive experiences that generate happiness (Oliveira et al., 2020).

On the other hand, the results of this research revealed that tourist happiness has a causal relationship with the intention to revisit a tourist destination, with β = 0.921; in this regard, previous research supports that it is important for tourist destinations to focus their efforts on aligning marketing strategies in order to make their visitors happy, which encourages tourists to have the intention to repeat the experiences lived and experience well-being again and again (Abbasi et al., 2021; Cham et al., 2022; Heydari Fard et al., 2021; Peng et al., 2023; Soliman, 2021).

The findings also support a causal relationship between tourist happiness and the intention to recommend a tourist destination, with β = 0.451; these results suggest that a happy tourist will undoubtedly be an agent capable of recommending a tourist destination, serving as support in communication and promotion (X. Liang & Xue, 2021), since it is known that when tourists feel satisfied during their stay at a destination, they are more likely to want to share their positive experiences with other people, which can generate additional benefits for the destination in terms of reputation and attracting potential tourists (Manyangara et al., 2023).

This study also found a strong causal relationship between the intention to revisit and recommend a tourist destination, with β = 0.464, highlighting that for satisfied tourists, this is their priority among the options when deciding on a tourist destination, and as a consequence they become bearers of positive experiences with friends, family and other social circles, which would allow them to enhance the promotion of the destination through word of mouth and personal recommendations, a key factor in the decision making of future tourists (Güçer et al., 2017; Heydari Fard et al., 2021).

The findings of this research have managerial implications relevant to the management of tourism destinations. In principle, the evidence that destination image significantly influences brand value and tourist happiness underlines the need for investment in marketing strategies that reinforce an attractive and memorable image of tourism destinations. This includes improving infrastructure, ensuring the quality of services and promoting authentic experiences that generate positive emotions. Furthermore, given that tourist happiness has a strong causal relationship with the intention to return and recommend the destination, tourism companies should prioritize the design of experiences that exceed visitors’ expectations, focusing on satisfaction and loyalty. This not only encourages repeat visits but also turns tourists into ambassadors for the company, promoting its reputation through personal recommendations and word of mouth. In addition, branding strategies should focus on maintaining and communicating consistently high brand equity, using positive testimonials from happy tourists as a tool to attract new visitors even in challenging economic times.

6. Limitations and Future Research

Although this study focused on collecting information and gaining specific knowledge of the tourist destination of the San Martín Region of Peru, the results could not be generalized, so it is recommended that for future studies, other tourist destinations should be addressed in order to have a more general understanding of the perception of tourists.

In addition, 425 surveys were collected in this research; however, an analysis of the possible gaps in perception between men and women, or according to age, was not carried out, so future studies could focus on addressing this aspect. It is very important to identify the perceptions of different demographic groups, which would also allow recognizing the specific patterns and preferences of the study population, with this information being useful when designing personalized and effective marketing strategies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.J.-G. and D.Y.M.-L.; methodology, O.E.H.; software, E.C.L.; validation, J.J.C.-T., D.Y.M.-L. and D.J.-G.; formal analysis, J.J.C.-T.; investigation, E.C.L.; resources, O.E.H.; data curation, D.J.-G.; writing—original draft preparation, D.Y.M.-L. and O.E.H.; writing—review and editing, D.Y.M.-L.; visualization, E.C.L.; supervision, J.J.C.-T.; project administration, O.E.H. and J.J.C.-T.; funding acquisition, D.J.-G. and E.C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by Universidad Peruana Unión.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Institutional Research Ethics Committee of the Graduate School of the Universidad Peruana Unión approved the study on 28 December 2023, with protocol code 2023-CE-EPG-00181. The study was carried out under the Declaration of Helsinki’s standards.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abbasi, G. A., Kumaravelu, J., Goh, Y.-N., & Dara Singh, K. S. (2021). Understanding the intention to revisit a destination by expanding the theory of planned behaviour (TPB). Spanish Journal of Marketing—ESIC, 25(2), 282–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akgün, A. E., Senturk, H. A., Keskin, H., & Onal, I. (2020). The relationships among nostalgic emotion, destination images and tourist behaviors: An empirical study of Istanbul. Journal of Destination Marketing and Management, 16, 100355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ampountolas, A. (2019). Peer-to-peer marketplaces: A study on consumer purchase behavior. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, 2(1), 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton, C., Camarero, C., & Laguna-Garcia, M. (2021). Culinary tourism experiences: The effect of iconic food on tourist intentions. Tourism Management Perspectives, 40, 100911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, F., Guerreiro, M., Pinto, P., & Ghaderi, Z. (2024). From tourist experience to satisfaction and loyalty: Exploring the role of a sense of well-being. Journal of Travel Research, 63(8), 1989–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bimonte, S., & Faralla, V. (2012). Tourist types and happiness a comparative study in Maremma, Italy. Annals of Tourism Research, 39(4), 1929–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bimonte, S., & Faralla, V. (2015). Happiness and outdoor vacations appreciative versus consumptive tourists. Journal of Travel Research, 54(2), 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, S., Pradhan, S., Bashir, M., & Roy, S. K. (2022). Customer-based place brand equity and tourism: A regional identity perspective. Journal of Travel Research, 61(3), 511–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B. M., & Byrne, B. M. (2013). Structural equation modeling with EQS (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cham, T.-H., Cheah, J.-H., Ting, H., & Memon, M. A. (2022). Will destination image drive the intention to revisit and recommend? Empirical evidence from golf tourism. International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship, 23(2), 385–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A., Suryadipura, D., Kostini, N., & Miftahuddin, A. (2021). An integrative model of cognitive image and city brand equity. Geojournal of Tourism and Geosites, 35(2), 364–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, W.-C., Wan Ibrahim, W. H., Lo, M.-C., Mohamad, A. A., Ramayah, T., & Chin, C.-H. (2022). Controllable drivers that influence tourists’ satisfaction and revisit intention to Semenggoh Nature Reserve: The moderating impact of destination image. Journal of Ecotourism, 21(2), 147–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.-J. (2021). Experiential marketing, brand image and brand loyalty: A case study of Starbucks. British Food Journal, 123(1), 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-J., & Li, W.-C. (2020). A study on the hot spring leisure experience and happiness of Generation X and Generation Y in Taiwan. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 25(1), 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., Zhang, K., & Huang, Y. (2023). Effect of social loneliness on tourist happiness: A mediation analysis based on smartphone usage. Sustainability, 15(11), 8760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, N. T. K., & Pham, H. (2022). The moderating role of eco-destination image in the travel motivations and ecotourism intention nexus. Journal of Tourism Futures, 10, 317–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, J. E. (2020). Applied structural equation modeling using AMOS; basic to advanced techniques. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Tarrillo, J. J., Haro-Zea, K. L., & Tarqui, E. E. A. (2023). Personality and image as predictors of the intention to revisit and recommend tourist destinations. Innovative Marketing, 19(1), 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuesta-Valiño, P., Gutiérrez-Rodríguez, P., & Núnez-Barriopedro, E. (2022). The role of consumer happiness in brand loyalty: A model of the satisfaction and brand image in fashion. Corporate Governance, 22(3), 458–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dam, S. M., & Dam, T. C. (2021). Relationships between service quality, brand image, customer satisfaction, and customer loyalty. Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business, 8(3), 585–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayzullaev, K., Cassel, S. H., & Brandt, D. (2021). Destination image in Uzbekistan–heritage of the Silk Road and nature experience as the core of an evolving Post Soviet identity. Service Industries Journal, 41(7–8), 446–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galiano-Coronil, A., Blanco-Moreno, S., Tobar-Pesantez, L., & Gutiérrez-Montoya, G. (2023). Social media impact of tourism managers: A decision tree approach in happiness, social marketing and sustainability. Journal of Management Development, 42(6), 436–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholipour, H. F., Tajaddini, R., & Foroughi, B. (2022). International tourists’ spending on traveling inside a destination: Does local happiness matter? Current Issues in Tourism, 26, 2027–2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godovykh, M., Ridderstaat, J., & Fyall, A. (2023). The well-being impacts of tourism: Long-term and short-term effects of tourism development on residents’ happiness. Tourism Economics, 29(1), 137–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, T., & Yi, Y. (2018). The effect of service quality on customer satisfaction, loyalty, and happiness in five Asian countries. Psychology & Marketing, 35(6), 427–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güçer, E., Bağ, C., & Altınay, M. (2017). Consumer behavior in the process of purchasing tourism product in social media. Journal of Business Research-Turk, 9(1), 381–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. B., William, J. B., & Rolph, A. (2020). Multivariate data analysis (Vol. 12). Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Heydari Fard, M., Sanayei, A., & Ansari, A. (2021). Determinants of medical tourists’ revisit and recommend intention. International Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Administration, 22(4), 429–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z., Huang, S., Yang, Y., Tang, Z., Yang, Y., & Zhou, Y. (2021). In pursuit of happiness: Impact of the happiness level of a destination country on Chinese tourists’ outbound travel choices. International Journal of Tourism Research, 23(5), 713–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawahar, D., & Muhammed, M. K. A. (2022). Product–place image and destination brand equity: Special reference to “Kerala is an ayurvedic destination”. Journal of Place Management and Development, 15(3), 248–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, S., & Kaur, M. (2020). Behavioral intentions of heritage tourists: Influential variables on recommendations to visit. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 15(5), 511–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacárcel, F. (2025). Digital technologies, sustainable lifestyle, and tourism: How digital nomads navigate global mobility? Sustainable Technology and Entrepreneurship, 4(2), 100096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-C., Olasehinde-Williams, G., & Akadiri, S. S. (2021). Geopolitical risk and tourism: Evidence from dynamic heterogeneous panel models. International Journal of Tourism Research, 23(1), 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J., & Park, C. (2022). Customer engagement on social media, brand equity and financial performance: A comparison of the US and Korea. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 34(3), 454–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F., Shang, Y., & Su, Q. (2023). The influence of immersion on tourists’ satisfaction via perceived attractiveness and happiness. Tourism Review, 78(1), 122–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., He, Z., Li, Y., Huang, T., & Liu, Z. (2023). Keep it real: Assessing destination image congruence and its impact on tourist experience evaluations. Tourism Management, 97, 104736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.-H., & Lai, I. K. W. (2023). Tea tourism: Designation of origin brand image, destination image, and visit intention. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 29(3), 409–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X., & Xue, J. (2021). Mediating effect of destination image on the relationship between risk perception of smog and revisit intention: A case of Chengdu. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 26(9), 1024–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieven, T., & Hildebrand, C. (2016). The impact of brand gender on brand equity: Findings from a large-scale cross-cultural study in ten countries. International Marketing Review, 33(2), 178–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Sanz, J., Penelas-Leguía, A., & Cuesta-Valiño, P. (2021). Application of the multiple classification analysis for the study of the relationships between destination image, satisfaction and loyalty in rural tourism. Journal of Tourism and Heritage Research, 4(2), 247–260. [Google Scholar]

- Luvsandavaajav, O., Narantuya, G., Dalaibaatar, E., & Zoltan, R. (2022). A Longitudinal Study of Destination Image, Tourist Satisfaction, and Revisit Intention. Journal of Tourism and Services, 13(24), 128–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, S., Zhou, Z., & Kim, W. G. (2024). Destination brand image and destination brand choice in the context of health crisis: Scale development. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 24(1), 134–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manhas, P., Manrai, L., & Manrai, A. (2016). Role of tourist destination development in building its brand image: A conceptual model. Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Science, 21(40), 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manyangara, M. E., Makanyeza, C., & Muranda, Z. (2023). The effect of service quality on revisit intention: The mediating role of destination image. Cogent Business and Management, 10(3), 2250264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, C., Vinhas da Silva, R., & Antova, S. (2021). Image, satisfaction, destination and product post-visit behaviours: How do they relate in emerging destinations? Tourism Management, 85, 104293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mimaki, C. A., Darma, G. S., Widhiasthini, N. W., & Basmantra, I. N. (2022). Predicting post-COVID-19 tourist’s loyalty: Will they come back and recommend? International Journal of Tourism Policy, 12(1), 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanan, P. (2024). Revitalizing ancient sites: Sustainable tourism strategies for preservation and community development. In Building community resiliency and sustainability with tourism development (pp. 171–195). IGI Global. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraga, E. T., Artigas, E. A. M., & Irigoyen, C. C. (2012). Desarrollo y propuesta de una escala para medir la imagen de los destinos turísticos (IMATUR). Revista Brasileira de Gestao de Negocios, 14(45), 400–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, S., Agúndez, A. D. M., da Fonseca, J. F., & Chemli, S. (2020). Impacts of positive images of tourism destination exhibited in a film or TV production on its brand equity: The case of Portuguese consumers’ perspective. Transnational Marketing Journal, 8(2), 271–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, T., Araujo, B., & Tam, C. (2020). Why do people share their travel experiences on social media? Tourism Management, 78, 104041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J., Yang, X., Fu, S., & Huan, T. (2023). Exploring the influence of tourists’ happiness on revisit intention in the context of Traditional Chinese Medicine cultural tourism. Tourism Management, 94, 104647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinho, M., & Leal, F. (2024). AI-enhanced strategies to ensure new sustainable destination tourism trends among the 27 European Union member states. Sustainability, 16(22), 9844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primananda, P., Yasa, N., Sukaatmadja, I., & Setiawan, P. (2022). Trust as a mediating effect of social media marketing, experience, destination image on revisit intention in the COVID-19 era. International Journal of Data and Network Science, 6(2), 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragb, H., Mahrous, A. A., & Ghoneim, A. (2020). A proposed measurement scale for mixed-images destinations and its interrelationships with destination loyalty and travel experience. Tourism Management Perspectives, 35, 100677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, S., Correia, R., Gonçalves, R., Branco, F., & Martins, J. (2023). Digital Marketing’s Impact on Rural Destinations’ Image, Intention to Visit, and Destination Sustainability. Sustainability, 15(3), 2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satrya, I., Herdono, I., Sudiarta, I., Karya, D., & Cahyanto, I. (2024). Factors influencing revisit cycling tour in Bali, Indonesia: The role of tourist engagement, destination attribute, memorable tourist experience and environmental concern. International Journal of Sustainable Development and Planning, 19(8), 2861–2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senese, A., Ahmad, A., Maugeri, M., & Diolaiuti, G. (2025). Assessing the carbon footprint of the 2024 Italian K2 expedition: A path towards sustainable high-altitude tourism. Sustainability, 17(1), 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, M. (2021). Extending the theory of planned behavior to predict tourism destination revisit intention. International Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Administration, 22(5), 524–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H., Wang, R., Jin, X., & Zhang, Z. (2022). The effects of motivation, destination image and satisfaction on rural tourism tourists’ willingness to revisit. Sustainability, 14(19), 11938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasci, A. D. A. (2020). Exploring the analytics for linking consumer-based brand equity (CBBE) and financial-based brand equity (FBBE) of destination or place brands. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 16(1), 36–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, L., Leask, A., & Ensor, J. (2017). Understanding primary stakeholders’ multiple roles in hallmark event tourism management. Tourism Management, 59, 494–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, P. K. T., Nguyen, V. K., & Tran, V. T. (2021). Brand equity and customer satisfaction: A comparative analysis of international and domestic tourists in Vietnam. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 30(1), 180–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vittersø, J., Prebensen, N. K., Hetland, A., & Dahl, T. (2017). The emotional traveler: Happiness and engagement as predictors of behavioral intentions among tourists in northern Norway. Advances in Hospitality and Leisure, 13, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., & Guo, R. (2025). How does the metaverse tourism experience form tourists’ happiness: A mixed-methods study. Journal of Vacation Marketing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woyo, E., & Slabbert, E. (2023). Competitiveness factors influencing tourists’ intention to return and recommend: Evidence from a distressed destination. Development Southern Africa, 40(2), 243–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X., Fang, C., Lin, H., & Chen, J. (2022). A framework for quantitative analysis and differentiated marketing of tourism destination image based on visual content of photos. Tourism Management, 93, 104585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Yang, L., Jiang, L., Yang, Z., & Xu, H. (2024). Exploring the relationship between tourist involvement and the tourists’ authentic happiness from the perspective of constructive-developmental theory. Journal of Resources and Ecology, 15(3), 782–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).