Job Satisfaction, Perceived Performance and Work Regime: What Is the Relationship Between These Variables?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Job Satisfaction

2.2. Work Performance

Job Satisfaction and Work Performance

2.3. Work Regimes: Remote, Hybrid and Face-to-Face—Impacts and Perspectives

2.3.1. Remote Working

2.3.2. Hybrid Working

2.3.3. Face-to-Face Work

2.3.4. Model Comparison

2.4. Work Regime and Job Satisfaction

2.5. Working Regime and Job Performance

2.6. Job Satisfaction, Job Performance and Working Regime

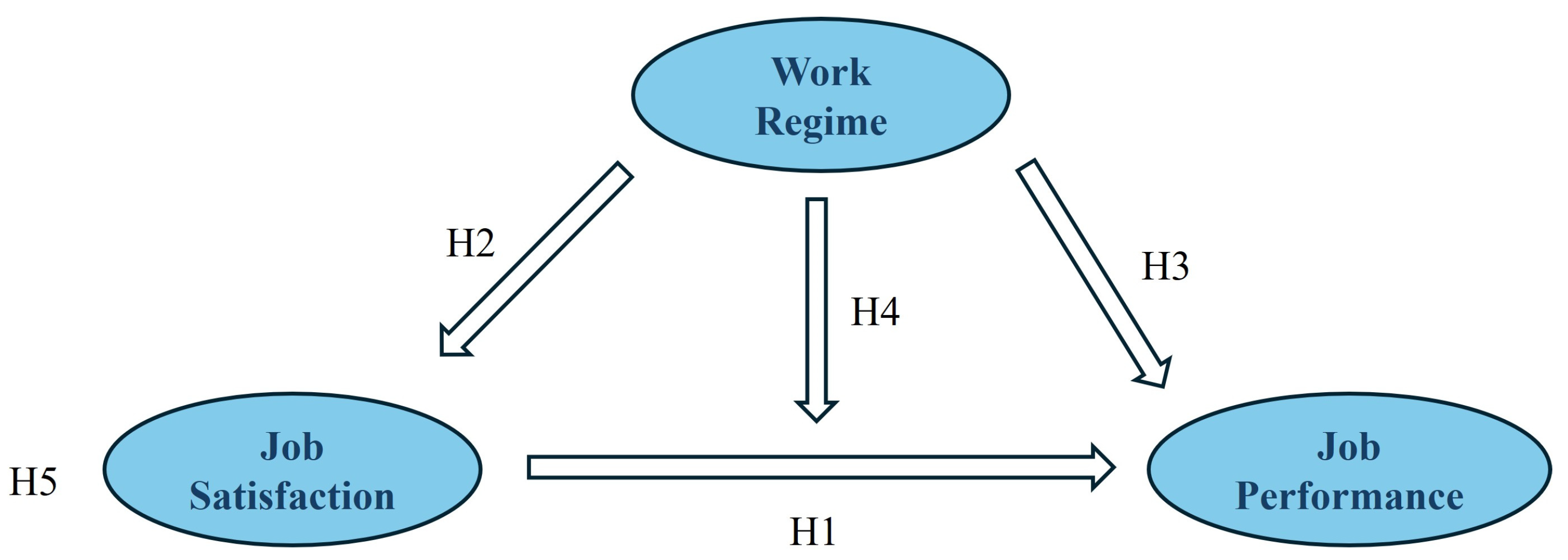

2.7. Mediating Effect

3. Methods

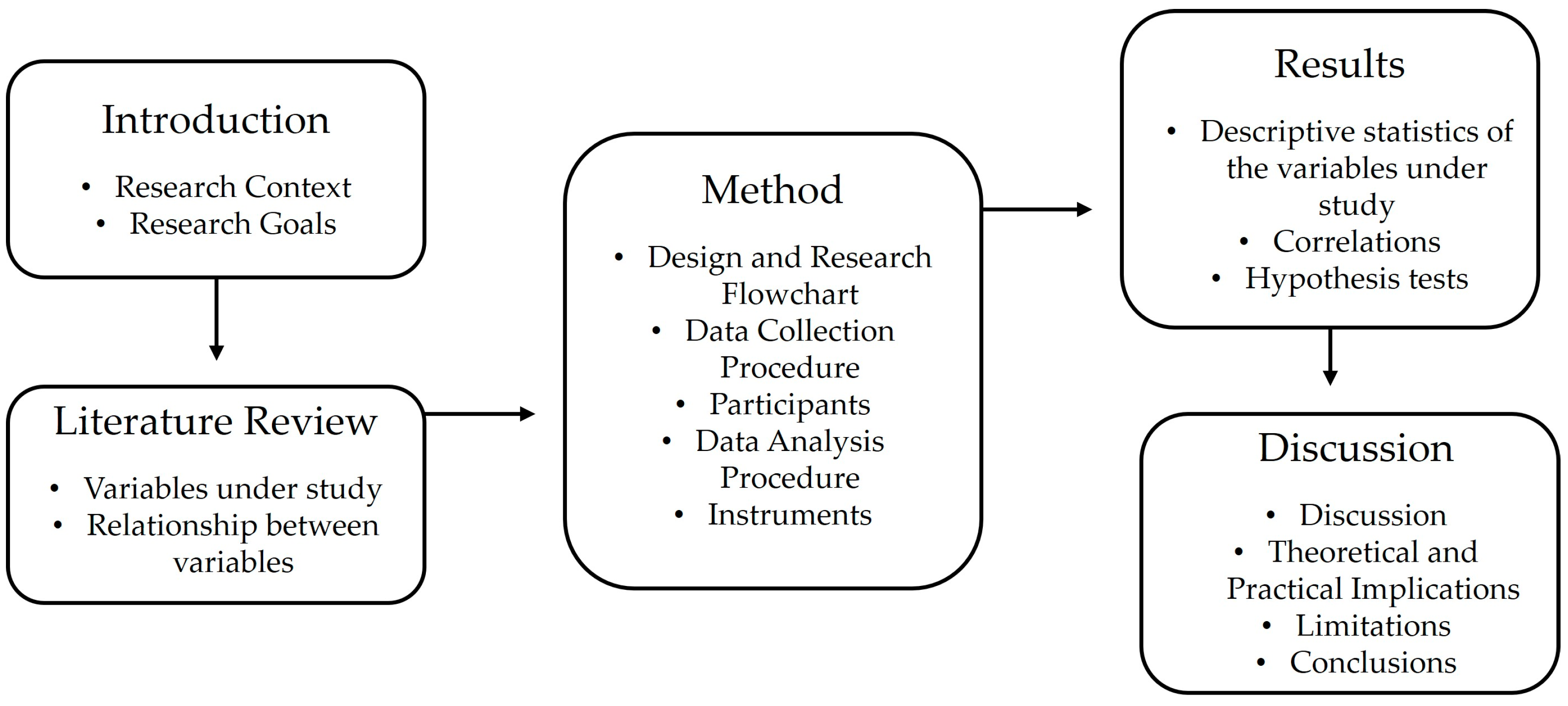

3.1. Design and Research Flowchart

3.2. Data Collection Procedure

3.3. Participants

3.4. Data Analysis Procedure

3.5. Instruments

4. Results

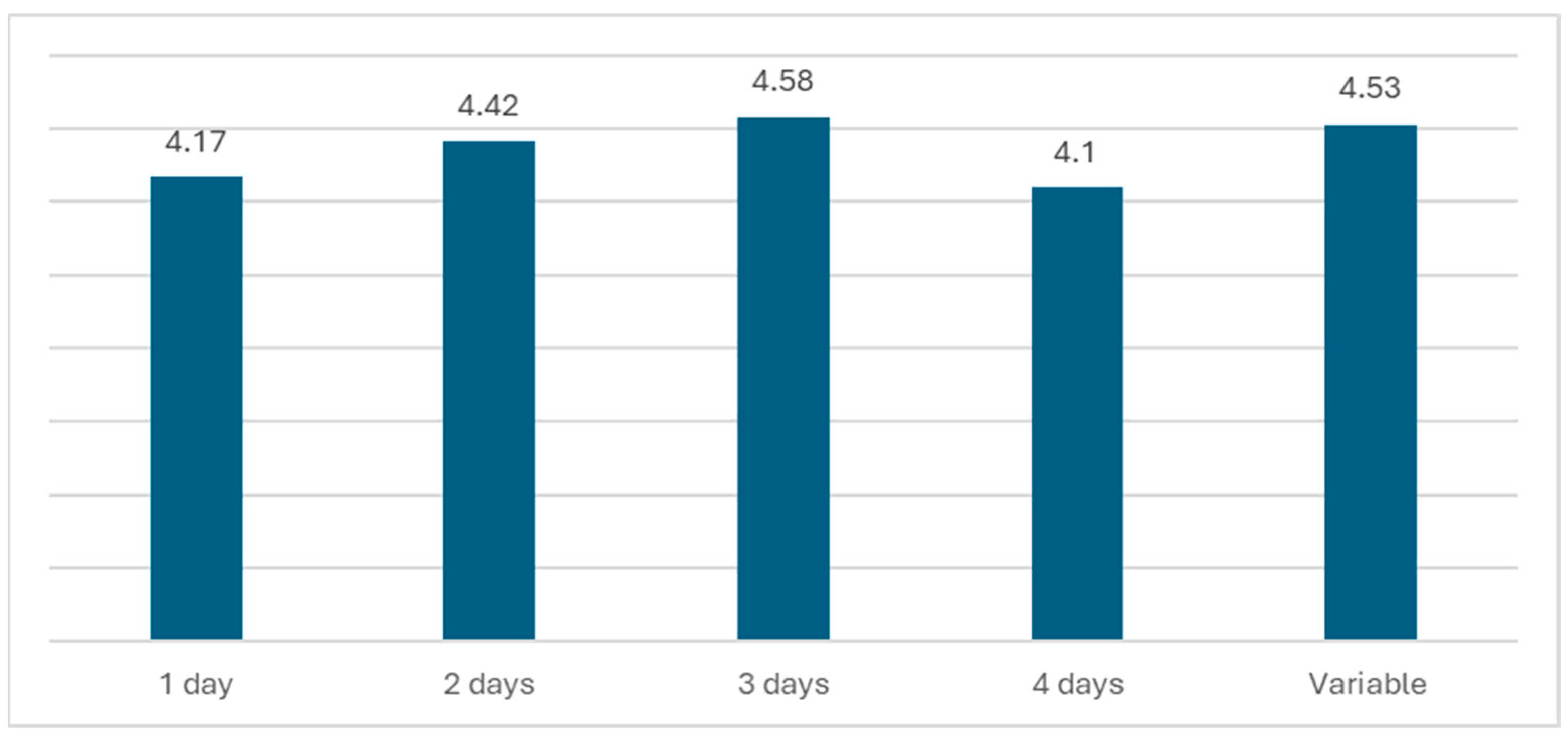

4.1. Descriptive Statistics of the Variables Under Study

4.2. Association Between the Variables Under Study

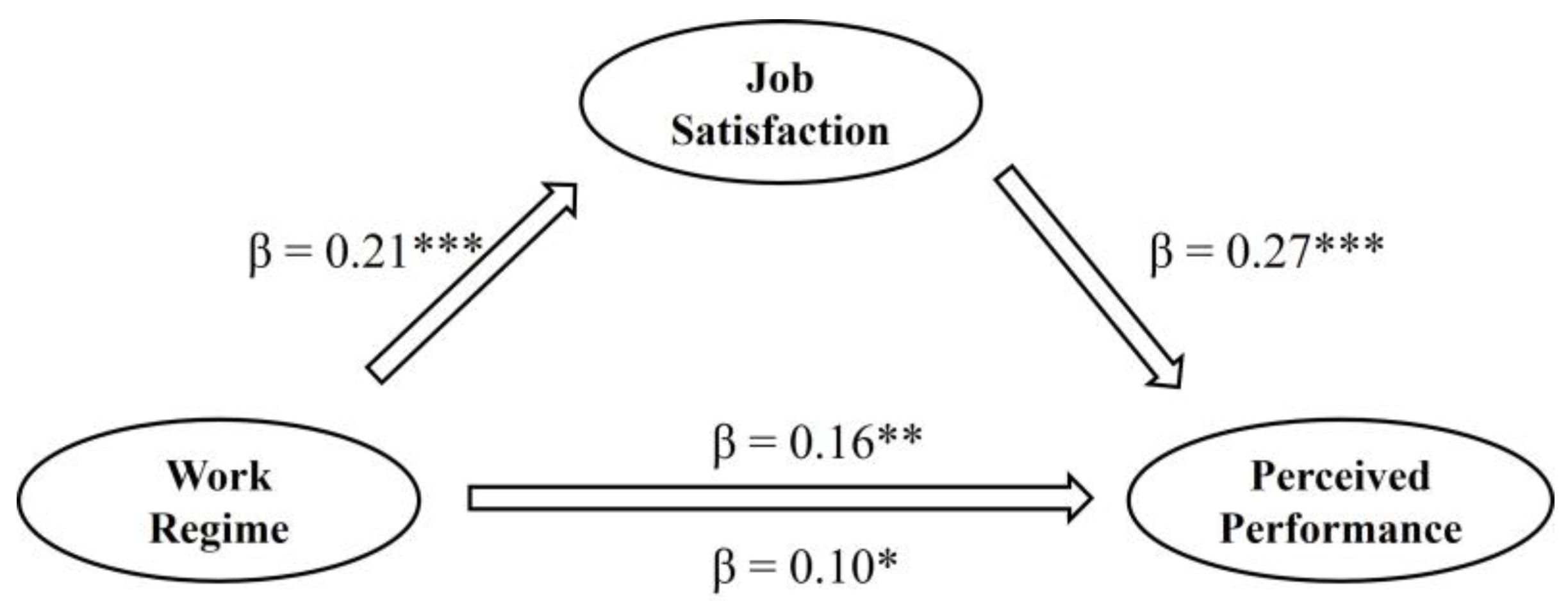

4.3. Hypotheses

5. Discussion

5.1. Limitations

5.2. Theoretical Implications

5.3. Practical Implications

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahmad, H., Ahmad, K., & Shah, I. A. (2010). Relationship between job satisfaction, job performance attitude towards work and organizational commitment. European Journal of Social Sciences, 18(2), 257–267. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, K. S., Grelle, D., Lazarus, E. M., Popp, E., & Gutierrez, S. L. (2024). Hybrid is here to stay: Critical behaviors for success in the new world of work. Personality and Individual Differences, 217, 112459. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0191886923003823 (accessed on 23 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- Aziri, B. (2011). Job satisfaction: A literature review. Management Research & Practice, 3(4), 7. Available online: https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=136e0e77dd3387e59954df73294d3e0114a08435 (accessed on 16 January 2025).

- Basalamah, S. A. (2021). The role of work motivation and work environment in improving job satisfaction. Golden Ratio of Human Resource Management, 1(2), 94–103. Available online: http://repository.umi.ac.id/2512/1/54-Article%20Text-1506-1-10-20220825.pdf (accessed on 27 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- Baxi, B., & Atre, D. (2024). Job satisfaction: Understanding the meaning, importance, and dimensions. Journal of Management and Entrepreneurship Research, 18(2), 34–39. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/380364720_Job_Satisfaction_Understanding_the_Meaning_Importance_and_Dimensions (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Bellmann, L., & Hübler, O. (2020). Job satisfaction and work-life balance: Differences between homework and work at the workplace of the company. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3660250 (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- Bergefurt, L., van den Boogert, P. F., Appel-Meulenbroek, R., & Kemperman, A. (2024). The interplay of workplace satisfaction, activity support, and productivity support in the hybrid work context. Building and Environment, 261, 111729. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0360132324005717 (accessed on 13 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- Bielińska-Dusza, E., Costa, R. L., & Zak, M. H. A. (2023). Study on the impact of remote working on the satisfaction and experience of IT workers in Poland. Forum Scientiae Oeconomia, 11(4), 9–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, N., Liang, J., Roberts, J., & Ying, Z. J. (2015). Does working from home work? Evidence from a Chinese experiment. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 130(1), 165–218. Available online: https://wellesu.com/10.1093/qje/qju032 (accessed on 1 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Bowling, N. A., Sessa, V. I., & Notari, C. (2021). Critical evaluation of the literature and a call for future research. In V. I. Sessa, & N. A. Bowling (Eds.), Essentials of job attitudes and other workplace psychological constructs (pp. 307–325). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brayfield, A. H., & Rothe, H. F. (1951). An index of job satisfaction. Journal of Applied Psychology, 35, 307–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, A., & Cramer, D. (2003). Análise de dados em ciências sociais. Introdução às técnicas utilizando o SPSS para windows (3rd ed.). Celta. [Google Scholar]

- Buła, P., Thompson, A., & Żak, A. A. (2024). Nurturing teamwork and team dynamics in a hybrid work model. Central European Management Journal, 32(3), 475–489. Available online: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/cemj-12-2022-0277/full/html (accessed on 10 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Capone, V., Schettino, G., Marino, L., Camerlingo, C., Smith, A., & Depolo, M. (2024). The new normal of remote work: Exploring individual and organizational factors affecting work-related outcomes and well-being in academia. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1340094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carnevale, J. B., & Hatak, I. (2020). Employee adjustment and well-being in the era of COVID-19: Implications for human resource management. Journal of Business Research, 116, 183–187. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0148296320303301 (accessed on 10 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Chmeis, S. T. J., & Zeine, H. M. (2024). The effect of remote work on employee performance. Asian Business Research, 9(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, P., Foroughi, C., & Larson, B. (2021). Work-from-anywhere: The productivity effects of geographic flexibility. Strategic Management Journal, 42(4), 655–683. Available online: https://www.wellesu.com/10.1002/smj.3251 (accessed on 14 December 2024). [CrossRef]

- Corral, R. J. P. (2024). Impact of hybrid and on-site work arrangements on employee motivation and job satisfaction in the BPO industry: A cross-sectional study. Open Journal of Social Sciences, 12(2), 205–230. Available online: https://www.scirp.org/journal/paperinformation?paperid=131322 (accessed on 17 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Finney, S. J., & DiStefano, C. (2013). Nonnormal and categorical data in structural equation modeling. In G. R. Hancock, & R. O. Mueller (Eds.), Structural equation modeling: A second course (2nd ed., pp. 439–492). IAP Information Age Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaio Santos, G., & Cabral-Cardoso, C. (2008). Work-family culture in academia: A gendered view of work-family conflict and coping strategies. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 23(6), 442–457. Available online: https://wellesu.com/10.1108/17542410810897553 (accessed on 2 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed.). Sage Publications Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Hanzis, A., & Hallo, L. (2024). The experiences and views of employees on hybrid ways of working. Administrative Sciences, 14(10), 263. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3387/14/10/263 (accessed on 10 December 2024). [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2022). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (Vol. 3). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inayat, W., & Khan, J. M. (2021). A study of job satisfaction and its effect on the performance of employees working in private sector organizations, Peshawar. Education Research International, 2021(1), 1751495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inceoglu, I., Thomas, G., Chu, C., Plans, D., & Gerbasi, A. (2018). Leadership behavior and employee well-being: An integrated review and a future research agenda. The Leadership Quarterly, 29(1), 179–202. Available online: https://wellesu.com/10.1016/j.leaqua.2017.12.006 (accessed on 7 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Jamaludin, N. L., & Kamal, S. A. (2023). The relationship between remote work and job satisfaction: The mediating role of perceived autonomy. Information Management and Business Review, 15(3), 10–22. Available online: https://ojs.amhinternational.com/index.php/imbr/article/view/3453/2202 (accessed on 5 January 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaß, L., Klußmann, A., Harth, V., & Mache, S. (2024). Job demands and resources perceived by hybrid working employees in German public administration: A qualitative study. Journal of Occupational Medicine and Toxicology, 19(1), 28. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s12995-024-00426-5 (accessed on 10 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Jöreskog, K. G., & Sörbom, D. (1993). LISREL8: Structural equation modelling with the SIMPLIS command language. Scientific Software International. [Google Scholar]

- Kara, D., Kim, H., Lee, G., & Uysal, M. (2018). The moderating effects of gender and income between leadership and quality of work life (QWL). International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 30(3), 1419–1435. Available online: https://wellesu.com/10.1108/IJCHM-09-2016-0514 (accessed on 5 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- Katebi, A., HajiZadeh, M. H., Bordbar, A., & Salehi, A. M. (2022). The relationship between “job satisfaction” and “job performance”: A meta-analysis. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management, 23, 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keppler, S. M., & Leonardi, P. M. (2023). Building relational confidence in remote and hybrid work arrangements: Novel ways to use digital technologies to foster knowledge sharing. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 28(4), zmad020. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/jcmc/article/28/4/zmad020/7210240 (accessed on 15 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- Kurdy, D. M., Al-Malkawi, H. A. N., & Rizwan, S. (2023). The impact of remote working on employee productivity during COVID-19 in the UAE: The moderating role of job level. Journal of Business and Socio-Economic Development, 3(4), 339–352. Available online: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/jbsed-09-2022-0104/full/html (accessed on 14 December 2024). [CrossRef]

- Lauring, J., & Jonasson, C. (2025). What is hybrid work? Towards greater conceptual clarity of a common term and understanding its consequences. Human Resource Management Review, 35(1), 101044. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1053482224000342 (accessed on 1 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Liu, W., Zhao, S., Shi, L., Zhang, Z., Liu, X., Li, L., Duan, X., Li, G., Lou, F., Jia, X., Fan, L., Sun, T., & Ni, X. (2018). Workplace violence, job satisfaction, burnout, perceived organisational support and their effects on turnover intention among Chinese nurses in tertiary hospitals: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open, 8(6), e019525. Available online: https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/bmjopen/8/6/e019525.full.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2024). [CrossRef]

- Mabaso, C. M., & Manuel, N. (2024). Performance management practices in remote and hybrid work environments: An exploratory study. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 50(1), a2202. Available online: https://sajip.co.za/index.php/sajip/article/view/2202/4082 (accessed on 15 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- McCallum, R., Browne, M., & Sugawara, H. (1996). Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structural modelling. Psychological Methods, 1, 130–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P. K. (2013). Job satisfaction. IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 14(5), 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustajab, D. (2024). Exploring the effectiveness of remote and hybrid work policies: A literature review on workforce management practices. Jurnal Manajemen Bisnis, 11(2), 891–908. Available online: https://jurnal.fe.umi.ac.id/index.php/JMB/article/view/798 (accessed on 15 December 2024). [CrossRef]

- Neves, P., Almeida, P., & Velez, M. J. (2018). Reducing intentions to resist future change: Combined effects of commitment-based HR practices and ethical leadership. Human Resource Management, 57(1), 249–261. Available online: https://wellesu.com/10.1002/hrm.21830 (accessed on 20 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, C. (2020, May 1). The impact of training and development, job satisfaction and job performance on young employee retention. Job Satisfaction and Job Performance on Young Employee Retention. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/35durkep (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- Orešković, T., Milošević, M., Košir, B. K., Horvat, D., Glavaš, T., Sadarić, A., Knoop, C.-I., & Orešković, S. (2023). Associations of working from home with job satisfaction, work-life Balance, and working-model preferences. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1258750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushpakumari, M. D. (2008). The impact of job satisfaction on job performance: An empirical analysis. In City Forum, 9(1), 89–105. [Google Scholar]

- Rachman, M. (2021). The impact of work stress and the work environment in the organization: How job satisfaction affects employee performance? Journal of Human Resource and Sustainability Studies, 9, 339–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, J. P., & Tri Prasetyo, Y. (2020, September 27–29). The impact of work-home arrangement on the productivity of employees during COVID-19 pandemic in the Philippines: A structural equation modelling approach. 6th International Conference on Industrial and Business Engineering (pp. 135–140), Macau, China. Available online: https://www.wellesu.com/10.1145/3429551.3429568 (accessed on 24 January 2025).

- Rupcic, N. (2024). Working and learning in a hybrid workplace: Challenges and opportunities. The Learning Organization, 31(2), 276–283. Available online: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/tlo-02-2024-303/full/html (accessed on 10 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- Saleem, U., & Khan, N. A. (2024). Remote work and job satisfaction: A case study of IT professionals. Administrative and Management Sciences Journal, 3(1), 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santillan, E. G., Santillan, E. T., Doringo, J. B., Pigao, K. J. F., & Von Francis, C. M. (2023). Assessing the impact of a hybrid work model on job execution, work-life balance, and employee satisfaction in a technology company. Journal of Business and Management Studies, 5(6), 13–38. Available online: https://www.al-kindipublisher.com/index.php/jbms/article/view/6271 (accessed on 14 December 2024). [CrossRef]

- Santos, M., Almeida, A., & Lopes, C. (2023). Satisfação laboral. Ajeogene Serviços Médicos Lda. [Google Scholar]

- Selvanayagam, A., Venkatakrishnan, S., & Ramkumar, N. (2025). The role of hybrid work models in enhancing employee well-being, productivity, and job satisfaction. South Eastern European Journal of Public Health, 26, 3049–3062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinval, J., & Marôco, J. (2020). Short index of job satisfaction: Validity evidence from Portugal and Brazil. PLoS ONE, 15(4), e0231474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tapasco-Alzatea, O., Giraldo-Garcíab, J., Corpas-Iguaránc, E. J., & Garcés-Gómezd, Y. A. (2024). Drivers of teleworker productivity: A systematic review of the empirical evidence. Communications in Science and Technology, 9(2), 386–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toscano, F., González-Romá, V., & Zappalà, S. (2024). The influence of working from home vs. working at the office on job performance in a hybrid work arrangement: A diary study. Journal of Business and Psychology, 40, 497–512. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10869-024-09970-7 (accessed on 9 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- Trochim, W. (2000). The research methods knowledge base (2nd ed.). Atomic Dog Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Vartiainen, M., & Vanharanta, O. (2023). Hybrid work: Definition, origins, debates and outlook. Eurofound. Available online: https://research.aalto.fi/en/publications/hybrid-work-definition-origins-debates-and-outlook (accessed on 14 January 2025).

- Vartiainen, M., & Vanharanta, O. (2024). True nature of hybrid work. Frontiers in Organizational Psychology, 2, 1448894. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/organizational-psychology/articles/10.3389/forgp.2024.1448894/full (accessed on 14 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- Waldrep, C. E., Fritz, M., & Glass, J. (2024). Preferences for remote and hybrid work: Evidence from the COVID-19 pandemic. Social Sciences, 13(6), 303. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-0760/13/6/303 (accessed on 23 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- Wang, B., Liu, Y., Qian, J., & Parker, S. K. (2021). Achieving effective remote working during the COVID-19 pandemic: A work design perspective. Applied Psychology, 70(1), 16–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L. J., & Anderson, S. E. (1991). Job satisfaction and organizational commitment as predictors of organizational citizenship and in-role behaviors. Journal of Management, 91, 601–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Frequency | Percentage | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 209 | 63.0% |

| Male | 123 | 37.0% | |

| Educational qualifications | 12th-grade education or less | 91 | 27.4% |

| Bachelor’s degree | 146 | 44.0% | |

| Master’s degree or higher | 95 | 28.6% | |

| Marital Status | Single | 195 | 58.7% |

| Married/Facto Union | 120 | 36.1% | |

| Divorced/Separated | 13 | 3.9% | |

| Widowed | 4 | 1.2% | |

| Seniority | Less than 1 year | 59 | 17.8% |

| Between 1 and 3 years | 130 | 39.2% | |

| Between 4 and 6 years | 62 | 18.7% | |

| Between 7 and 10 years | 28 | 8.4% | |

| Between 10 and 15 years | 20 | 6.0% | |

| More than 15 years | 33 | 9.9% | |

| Type of Contract | Uncertain term | 44 | 13.3% |

| Fixed-term | 70 | 21.1% | |

| Open-ended | 198 | 59.6% | |

| Other | 20 | 6.0% | |

| Sector of Activity | Public | 46 | 13.9% |

| Private | 277 | 83.4% | |

| Public/Private | 9 | 2.7% | |

| Work Regime | Face-to-face | 214 | 64.5% |

| Hybrid | 97 | 29.2% | |

| Remote | 21 | 6.3% | |

| Days in Hybrid Regime | 1 day | 12 | 12.4% |

| 2 days | 34 | 35.1% | |

| 3 days | 24 | 24.7% | |

| 4 days | 4 | 4.1% | |

| Variable | 23 | 23.7% |

| Face-to Face | Hybrid | Remote | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 130 (62.2%) | 67 (32.1%) | 12 (5.7%) |

| Male | 84 (68.3%) | 30 (24.4%) | 9 (7.3%) | |

| Educational qualifications | 12th-grade education or less | 76 (83.5%) | 12 (13.2%) | 3 (3.3%) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 86 (58.9%) | 50 (34.2%) | 10 (6.8%) | |

| Master’s degree or higher | 52 (54.7%) | 35 (36.8%) | 8 (8.4%) | |

| Marital Status | Single | 128 (65.6%) | 55 (28.2%) | 12 (6.2%) |

| Married/Facto Union | 74 (61.7%) | 38 (31.7%) | 8 (6.7%) | |

| Divorced/Separated | 9 (69.2%) | 3 (23.1%) | 1 (7.7%) | |

| Widowed | 3 (75%) | 1 (25%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Seniority | Less than 1 year | 35 (59.3%) | 22 (37.3%) | 2 (3.4%) |

| Between 1 and 3 years | 84 (64.6%) | 36 (27.7%) | 10 (7.7%) | |

| Between 4 and 6 years | 35 (56.5%) | 20 (32.3%) | 7 (11.3%) | |

| Between 7 and 10 years | 19 (67.9%) | 8 (28.6%) | 1 (3.6%) | |

| Between 10 and 15 years | 17 (85%) | 3 (15%) | 0 (0%) | |

| More than 15 years | 24 (72.7%) | 8 (24.2%) | 1 (3%) | |

| Type of Contract | Uncertain term | 34 (73.3%) | 8 (18.2%) | 2 (4.5%) |

| Fixed-term | 50 (71.4%) | 17 (24.3%) | 3 (4.3%) | |

| Open-ended | 117 (59.1%) | 65 (32.8%) | 16 (8.1%) | |

| Other | 13 (65%) | 7 (35%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Sector of Activity | Public | 36 (78.3%) | 9 (19.6%) | 1 (2.2%) |

| Private | 170 (61.4%) | 88 (31.8%) | 19 (6.9%) | |

| Public/Private | 8 (88.9%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (11.1%) |

| Variable | t | df | p | d | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Job satisfaction | 13.42 *** | 331 | <0.001 | 0.74 | 3.59 | 0.04 |

| Perceived Performance | 46.78 *** | 331 | <0.001 | 2.57 | 4.23 | 0.03 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| - | ||

| 0.19 *** | - | |

| 0.18 *** | 0.28 *** | - |

| Independent Variable | Dependent Variable | F | p | R2 | β | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Job Satisfaction | Perceived Performance | 29.93 *** | <0.001 | 0.08 | 0.29 *** | <0.001 |

| Variável | ANOVA One Way | Work Regime. A | Work Regime. B | TuKey HSD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | p | Dif. In Means (A–B) | p | |||

| Job Satisfaction | 7.40 *** | <0.001 | Face-to-face | Hybrid | −0.30 ** | 0.005 |

| Remote | −0.48 * | 0.019 | ||||

| Variable | ANOVA One Way | Work Regime. A | Work Regime. B | TuKey HSD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | p | Dif. In Means (A–B) | p | |||

| Perceived Performance | 6.80 ** | 0.001 | Face-to-face | Hybrid | −0.22 ** | <0.001 |

| Remote | −0.12 | 0.562 | ||||

| Variable | B | SE | t | p | 95% IC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Job Satisfaction → Perceived Performance (R2 = 0.10; p < 0.001) | |||||

| Constant | 4.29 *** | 0.03 | 157.46 *** | <0.001 | [4.23; 4.34] |

| Job Satisfaction | 0.17 *** | 0.04 | 4.95 *** | <0.001 | [0.11; 0.24] |

| Work Regime | 0.08 | 0.05 | 1.68 | 0.093 | [−0.01; 0.17] |

| JS*WR | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.65 | 0.514 | [−0.09; 0.18] |

| Indirect Effects | ||

|---|---|---|

| Estimates | 95% Confidence Interval with Bootstrap Correction | |

| Model | ||

| Total | 0.13 (0.04) | [0.4; 0.21] |

| WR → JS→ PP | 0.04 (0.01) | 0.02; 0.07] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pinheiro, A.; Palma-Moreira, A. Job Satisfaction, Perceived Performance and Work Regime: What Is the Relationship Between These Variables? Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 175. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15050175

Pinheiro A, Palma-Moreira A. Job Satisfaction, Perceived Performance and Work Regime: What Is the Relationship Between These Variables? Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(5):175. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15050175

Chicago/Turabian StylePinheiro, Angelie, and Ana Palma-Moreira. 2025. "Job Satisfaction, Perceived Performance and Work Regime: What Is the Relationship Between These Variables?" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 5: 175. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15050175

APA StylePinheiro, A., & Palma-Moreira, A. (2025). Job Satisfaction, Perceived Performance and Work Regime: What Is the Relationship Between These Variables? Administrative Sciences, 15(5), 175. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15050175