Unveiling Dynamic Capabilities in Public Procurement: Myths, Realities, and Strategic Transformation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Development and Characteristics of Dynamic Capabilities

2.2. Defining Attributes of Dynamic Capabilities

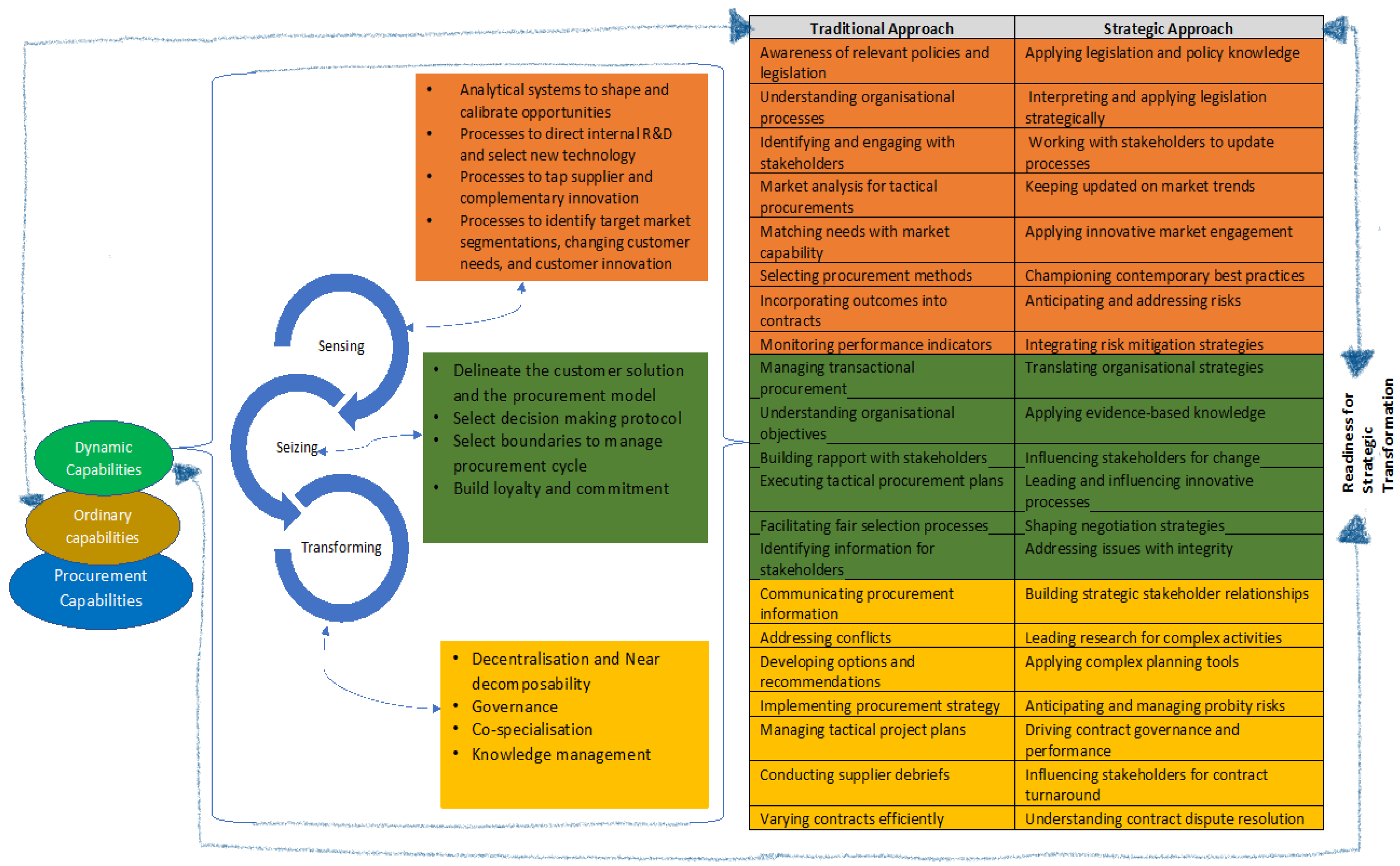

2.3. Dynamic Capabilities in Public Procurement: Sensing, Seizing, and Transforming

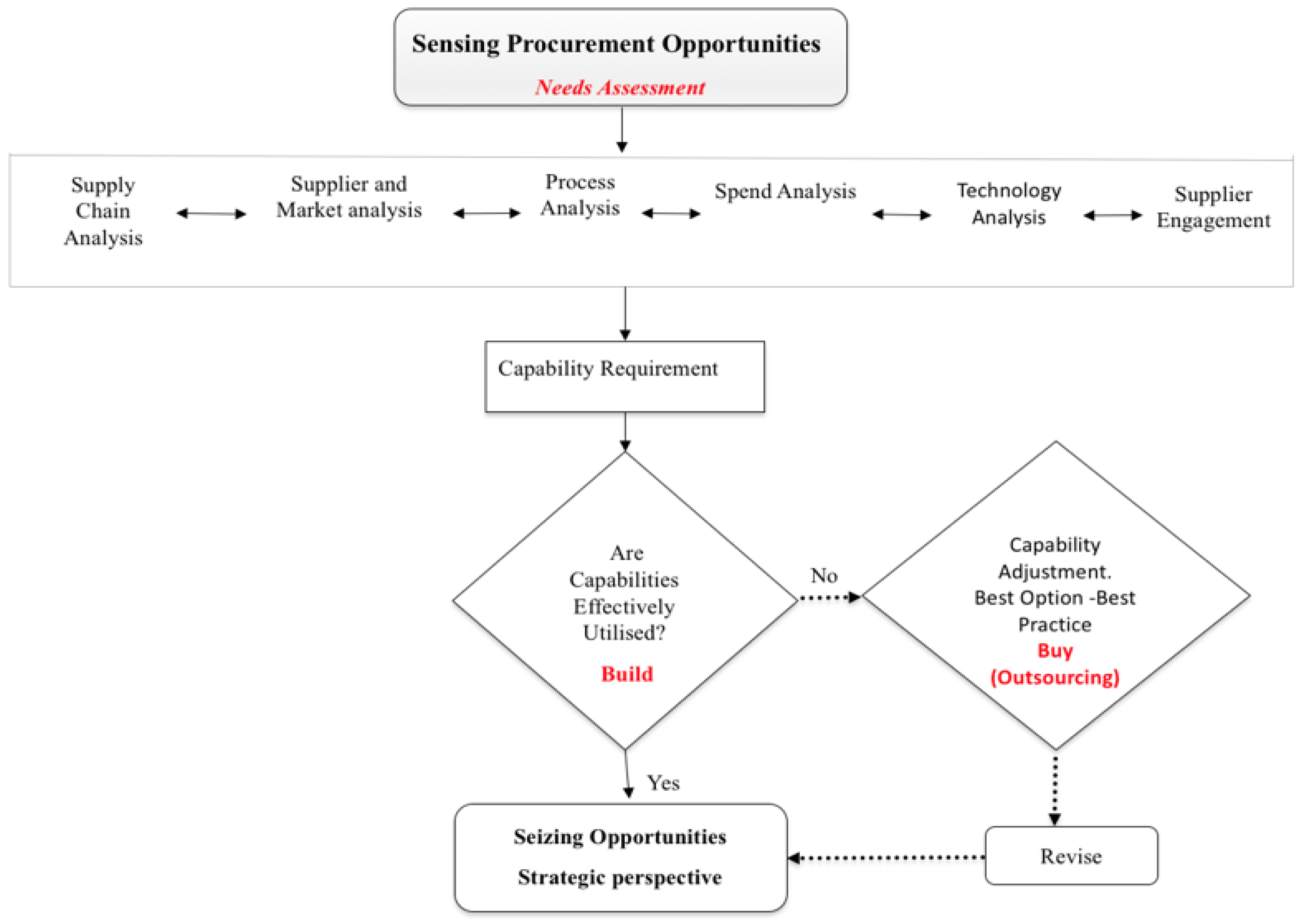

2.3.1. Sensing Capabilities in Public Procurement

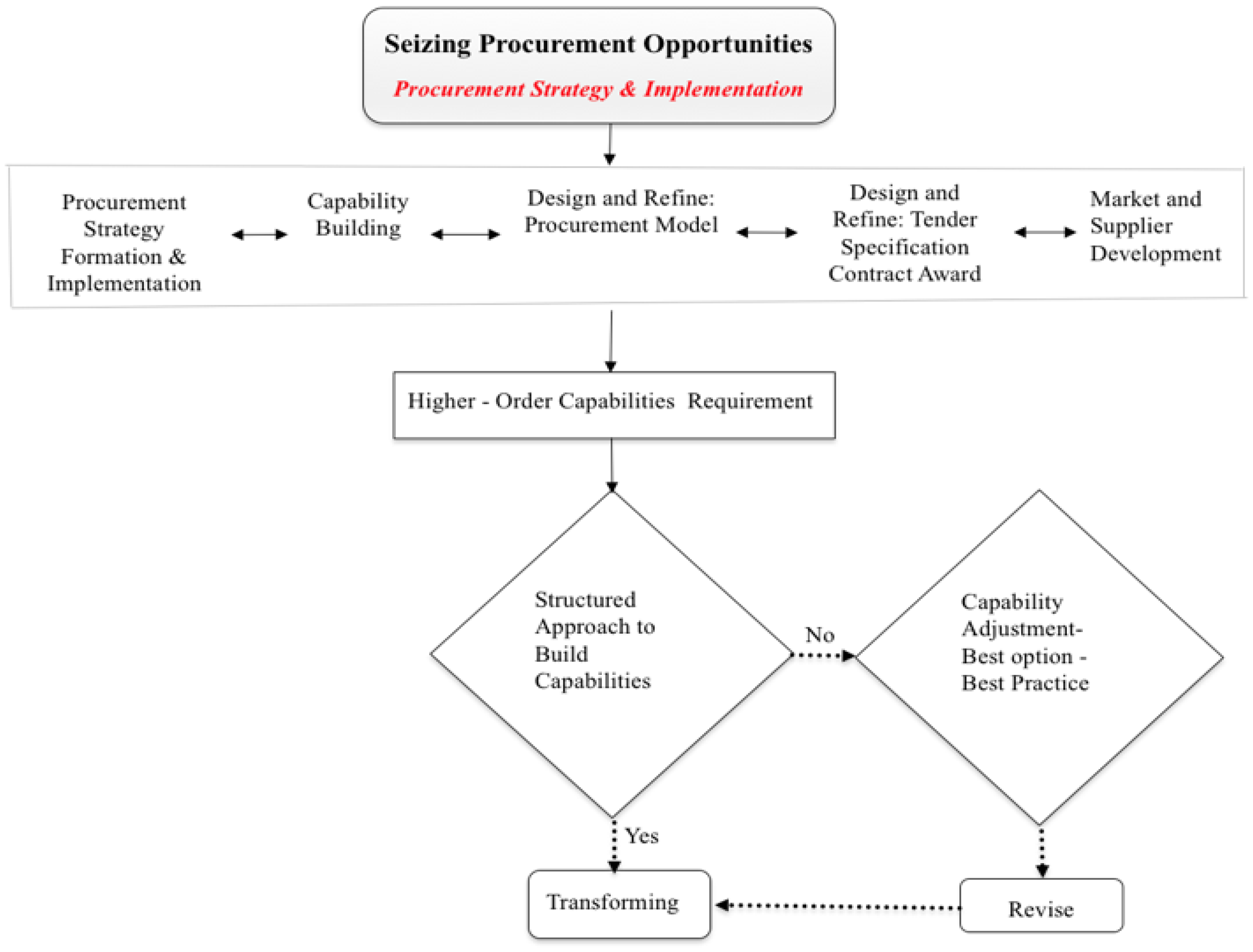

2.3.2. Seizing Capabilities in Public Procurement

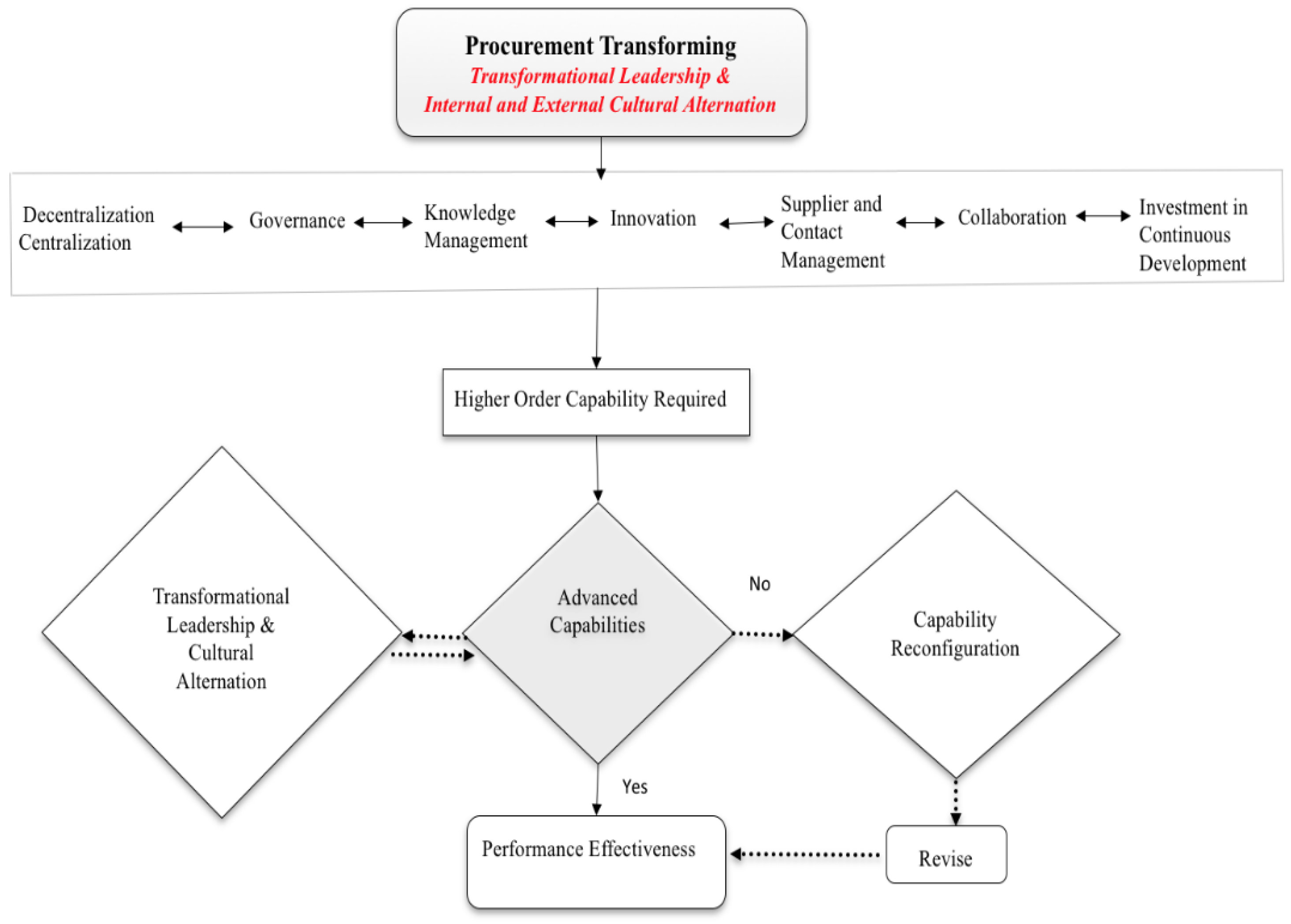

2.3.3. Transforming Capabilities in Public Procurement

2.4. Integrating Dynamic Capabilities in Public Sector Procurement

2.5. Implications for Policy and Practice

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection

3.1.1. Case Studies

- Organizational structure and procurement strategies.

- The integration of DCs (sensing, seizing, and transforming) in procurement processes.

- Challenges and enablers of strategic transformation.

- Diversity in expenditure levels: Councils with varying procurement budgets were chosen, ranging from GBP 98 million to GBP 390 million annually, to capture differences in financial constraints and strategic procurement responses.

- Strategic focus areas: The authorities represent different procurement priorities, including strategic procurement (CCC1 and CCC2), value integration (MCC), alignment with the Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015 (CCBC), and social-value-driven procurement (PCC and NCC).

- Geographical representation: Councils from different regions were selected to ensure a balanced view of procurement practices across Wales.

- Alignment with policy objectives: The councils reflect varying levels of engagement with policy frameworks such as sustainability, risk management, and economic growth.

- Stakeholder engagement: Each council provides a unique procurement structure, ensuring meaningful insights from focus groups and semi-structured interviews with procurement professionals and senior managers.

3.1.2. Semi-Structured Interviews

- The role of DCs in addressing procurement challenges.

- Strategies for fostering organizational agility and adaptability.

- Perceived barriers and enablers of strategic transformation.

3.1.3. Focus Groups

- Current procurement practices and challenges.

- The role of DCs in driving strategic outcomes.

- Opportunities for innovation and collaboration.

3.2. Data Analysis

- Familiarization: Transcripts from interviews and focus groups were reviewed to identify preliminary patterns and themes.

- Coding: Data were coded based on key concepts related to DCs, strategic transformation readiness, and procurement practices.

- Theme development: Codes were organized into broader themes, such as sensing capabilities, seizing capabilities, and transforming capabilities.

- Interpretation: The themes were synthesized to draw insights about the application of DCs in SPSP and the factors influencing strategic transformation readiness.

3.3. Methodological Rigor

- Triangulation: The use of multiple data sources (case studies, interviews, and focus groups) enhanced the credibility and robustness of the findings.

- Member checking: Preliminary findings were shared with participants to ensure accuracy and resonance with their experiences.

- Reflexivity: The researcher maintained a reflective journal to document biases and ensure a critical approach to data interpretation.

3.4. Contribution to the Literature

4. Findings

4.1. Public Procurement Micro-Foundations

4.1.1. Sensing Procurement Capabilities

4.1.2. Seizing Procurement Capabilities

4.1.3. Transforming Procurement Capabilities

4.2. Comparative Analysis and Implications

- Leadership and governance: Effective leadership is critical for fostering strategic alignment and driving procurement transformation. Councils with stable leadership, such as CCC1, exhibited stronger sensing, seizing, and transforming capabilities compared to those with frequent leadership changes, such as NCC.

- Stakeholder engagement: Collaborative relationships with internal and external stakeholders enhance procurement capabilities by fostering trust, transparency, and shared value creation. Councils like CCBC and CCC2 leveraged stakeholder engagement to address resource constraints and achieve strategic outcomes.

- Innovation and adaptability: The ability to adapt procurement practices to changing contexts and embrace innovation is essential for achieving long-term sustainability goals. PCC’s focus on commissioning and service model innovation illustrates the potential of strategic procurement to drive organizational change.

- Resource constraints: Limited capacity and resources present significant challenges for councils like MCC and NCC. Addressing these constraints through targeted investments and collaboration can enhance procurement capabilities and outcomes.

5. Unveiling Dynamic Capabilities in Strategic Public Sector Procurement: A Myth or Reality?

5.1. Sensing Capabilities: Bridging Awareness and Action

- Successes: WLAs like CCC1 and CCBC exhibited robust sensing capabilities through initiatives such as restructuring procurement functions, adopting category management (CM), and participating in collaborative procurement reviews. These efforts aligned their procurement practices with broader strategic objectives and external dynamics.

- Challenges: Conversely, WLAs such as NCC struggled with effective sensing due to partial CM implementation, leadership instability, and limited resources. These barriers hindered their ability to anticipate and respond to procurement needs, aligning with existing literature on bureaucratic constraints and limited access to timely information (Flynn & Davis, 2017).

5.2. Seizing Capabilities: Acting on Opportunities

- Proactive examples: WLAs like CCC1 and CCC2 leveraged seizing capabilities to drive procurement transformation. CCC1 restructured its procurement function to align with strategic goals, while CCC2 embraced collaboration with Pembrokeshire to enhance procurement efficiency and community benefits.

5.3. Transforming Capabilities: Driving Organizational Change

- Exemplary efforts: WLAs such as CCC1 and PCC demonstrated strong transforming capabilities through innovative service delivery models, stakeholder engagement, and procurement team expansions. These actions align with the literature emphasizing the importance of adaptive resource reallocation (Pee & Kankanhalli, 2016).

- Challenges: Other WLAs, like NCC, struggled to sustain transformation efforts due to leadership turnover, cultural resistance, and limited CM implementation. These barriers echo broader challenges in public sector transformation, where rigid structures inhibit sustained change (Hawrysz, 2021).

5.4. Synthesizing Insights: DCs in SPSP—Reality or Myth?

- Leadership: Stable, visionary leadership proved critical for fostering DCs, as seen in CCC1, while instability in councils like NCC inhibited progress.

- Cultural adaptability: Councils embracing innovation, such as PCC, were better positioned for procurement transformation than those resistant to change.

5.5. Bridging Theory and Practice

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adam, B., & Lindahl, A. (2019). Risk management and dynamic capabilities in procurement. Journal Procurement Studies, 10(4), 302–318. [Google Scholar]

- Ambrosini, V., & Bowman, C. (2009). What are dynamic capabilities and are they a useful construct in strategic management? International Journal of Management Reviews, 11(1), 29–49. [Google Scholar]

- Barreto, I. (2010). Dynamic capabilities: A review of past research and an agenda for the future. Journal of Management, 36(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breznik, L., & Lahovnik, M. (2016). Dynamic capabilities and competitive advantage: Findings from case studies. Management Decision, 54(2), 529–549. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A. (2016). Social research methods (5th ed.). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell, N. D., Roehrich, J. K., & Davies, A. C. (2009). Procuring complex performance in construction: London heathrow terminal 5 and private finance initiative hospital. Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management, 15, 178–186. [Google Scholar]

- Carmeli, A., & Tishler, A. (2004). Resources, capabilities, and the performance of industrial firms: A multivariate analysis. Management and Decision Economics, 25(6–7), 299–315. [Google Scholar]

- Easterby-Smith, M., Lyles, M. A., & Peteraf, M. A. (2009). Dynamic capabilities: Current debates and future directions. British Journal of Management, 20, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Easterby-Smith, M., & Prieto, M. (2008). Dynamic capabilities and knowledge management: An Integrative role for learning. British Journal of Management, 19(3), 235–249. [Google Scholar]

- Easterby-Smith, M., Thorpe, R., & Jackson, P. (2021). Management and business research. SAGE Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 532–550. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K. M., & Martin, J. A. (2000). Dynamic capabilities: What are they? Strategic Management Journal, 21(10–11), 1105–1121. [Google Scholar]

- Flynn, A., & Davis, P. (2017). Explaining SME participation and success in public procurement using a capability-based model of tendering. Journal of Public Procurement, 17(3), 337–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, A., & Davis, P. (2023). Public procurement: Principles, strategies, and practices. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hartley, J., & Rashman, L. (2018). Innovation and inter-organizational learning in the context of public service reform. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 84(2), 231–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawrysz, L. (2021). Dynamic capabilities affecting the functioning of e-administration in polish public administration entities. European Research Studies Journal, 24(2B), 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfat, C. E., Finkelstein, S., Mitchell, W., Peteraf, M., Singh, H., Teece, D., & Winter, S. (2007). Dynamic capabilities: Understanding strategic change in organisations. Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Helfat, C. E., & Peteraf, M. A. (2014). Managerial cognitive capabilities and microfoundation of dynamic capabilities. Strategic Management Journal, 36, 831–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kattel, R., & Mazzucato, M. (2018). Mission-oriented innovation policy and dynamic capabilities in the public sector. Industrial and Corporate Change, 27(5), 787–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kattel, R., & Mergel, I. (2023). Agility in public procurement: Lessons from crisis response. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 34(1), 120–135. [Google Scholar]

- Kay, N. M., Leih, S., & Teece, D. J. (2018). The role of emergence in dynamic capabilities: A restatement of the framework and some possibilities for future research. Industrial and Corporate Change, 27(4), 623–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G., Shin, B., Kim, K. K., & Lee, G. H. (2011). IT capabilities, process-oriented dynamic capabilities, and firm financial performance. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 12(7), 487–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, A. R., & Casey, M. A. (2015). Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research. SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Loader, K. (2007). The challenge of competitive procurement: Value for money versus small business support. Public Money and Management, 27, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, J. (2017). Dynamic capability and firm performance: The role of marketing capability and operations capability. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 64(4), 554–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, H. W., & Wilson, A. G. (2022). Dynamic capabilities and stakeholder theory explanation of superior performance among award-winning hospitals. International Journal of Healthcare Management, 15(3), 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndrecaj, V. (2018). A critical and analytical study of dynamic capabilities in strategic procurement: The case of six welsh local authorities. University of South Wales. [Google Scholar]

- Ndrecaj, V., Mason-Jones, R., Mohamed, H. M. A., Tlemsani, I., & Zaman, A. (2023a, May 16–17). Dynamic capabilities perspective for strategic public procurement: Rethinking procurement strategic proposition [Conference contribution]. 7th AMI Conference 2023, Cardiff, UK. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndrecaj, V., Mohamed Hashim, M. A., Mason-Jones, R., Ndou, V., & Tlemsani, I. (2023b). Exploring lean six sigma as dynamic capability to enable sustainable performance optimisation in times of uncertainty. Sustainability, 15, 16542. [Google Scholar]

- Ospina, S. M., Esteve, M., & Lee, S. (2018). Assessing qualitative studies in public administration research. Public Administration Review, 78(4), 593–605. [Google Scholar]

- Pablo, A., Reay, T., Dewald, R. J., & Casebeer, A. (2007). Identifying, enabling and managing dynamic capabilities in the public sector. Journal of Management Studies, 44(5), 687–708. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen, K. (2017). Transforming government service: The importance of dynamic capabilities. Electronic Government, An International Journal, 13(3), 203–223. [Google Scholar]

- Pee, L. G., & Kankanhalli, A. (2016). Interactions among factors influencing knowledge management in public-sector organizations: A resource-based view. Government Information Quarterly, 33(1), 88–199. [Google Scholar]

- Piening, E. P. (2013). Dynamic capabilities in public organisations. Public Management Review, 15(2), 209–245. [Google Scholar]

- Prieto, M. I., Revilla, E., & Rodriguez-Prado, B. (2009). Building dynamic capabilities in product development: How do contextual antecedent matters? Scandinavian Journal of Management, 25(3), 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salge, T. O., & Vera, A. (2011). Small steps that matter: Incremental learning, slack resources and organisational performance. British Journal of Management, 24(2), 156–173. [Google Scholar]

- Salvato, C., & Rerup, C. (2011). Beyond collective entities: Multilevel research on organisational routines and capabilities. Journal of Management, 37(2), 468–490. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, M. N. K., Lewis, P., & Thornhill, A. (2023). Research methods for business students (8th ed.). Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Schoemaker, P. J. H., Heaton, S., & Teece, D. (2018). Innovation, dynamic capabilities, and leadership. California Management Review, 61(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D. J. (2007). Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strategic Management Journal, 28(13), 1319–1350. [Google Scholar]

- Teece, D. J. (2010). Business models, business strategy and innovation. Long Range Planning: LRP, 43, 172–194. [Google Scholar]

- Teece, D. J. (2012). Dynamic capabilities: Routines versus entrepreneurial action. Journal of Management Studies, 49(8), 1395–1401. [Google Scholar]

- Teece, D. J. (2014). A dynamic capabilities-based entrepreneurial theory of the multinational enterprise. Journal of International Business Studies, 45(1), 8–37. [Google Scholar]

- Teece, D. J. (2018a). Business models and dynamic capabilities. Long Range Planning, 51(1), 40–49. [Google Scholar]

- Teece, D. J. (2018b). Dynamic capabilities as (workable) management systems theory. Journal of Management and Organisation, 24(3), 359–368. [Google Scholar]

- Teece, D. J. (2023). Dynamic capabilities: Foundations and future directions. Strategic Management Journal, 45(2), 342–361. [Google Scholar]

- Teece, D. J., Peteraf, M., & Leih, S. (2016). Dynamic capabilities and organisational agility: Risk, uncertainty, and strategy in the innovation economy. California Management Review, 58(4), 13–35. [Google Scholar]

- Teece, D. J., & Pisano, G. (1994). Dynamic capabilities of firms: An introduction. International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis. Available online: http://pure.iiasa.ac.at/4109/1/WP-94-103.pdf (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Teece, D. J., Pisano, G., & Shuen, A. (1990). Firm capabilities, resources, and the concept of strategy. CCC Working Paper 90-8. Centre for Research in Management, University of California, Berkeley. [Google Scholar]

- Teece, D. J., Pisano, G., & Shuen, A. (1997). Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 18(7), 509–533. [Google Scholar]

- Uyarra, E. (2010). Opportunities for innovation through local government procurement: A case study of greater Manchester. Research report. NESTA. [Google Scholar]

- Uyarra, E., Zabala-Iturriagagoitia, M., Flanagan, K., & Magro, E. (2020). Public procurement, innovation and industrial policy: Rationales, roles, capabilities and implementation. Research Policy, 49(1), 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, K. S., & Wäger, M. (2019). Building dynamic capabilities for digital transformation: An ongoing process of strategic renewal. Long Range Planning, 52(3), 326–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, S. G. (2003). Understanding dynamic capabilities. Strategic Management Journal, 24, 991–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. (2024). Public procurement in a post-pandemic world: Innovations and best practices. World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R. K. (2003). Case study research: Design and methods. SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R. K. (2014). Case study research: Design and methods (4th ed.). SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Zahra, S. A., & George, G. (2002). Absorptive capacity: A review, reconceptualization, and extension. Academy of Management Review, 27(2), 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zollo, M., & Winter, S. G. (2002). Deliberate learning and the evolution of dynamic capabilities. Organisation Science, 13(3), 339–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Description |

|---|---|

| Agility and Adaptability | Enables responsiveness to organizational and market changes (Teece, 2010, 2018a). |

| Learning Orientation | Facilitates continuous improvement and innovation through organizational learning (Mu, 2017). |

| Strategic Flexibility | Allows adaptation to competitive pressures and emerging opportunities (Breznik & Lahovnik, 2016). |

| Innovation and Entrepreneurship | Drives enterprise performance through innovative practices (Schoemaker et al., 2018). |

| Integration of Resources | Aligns internal and external resources for enhanced performance (Teece, 2012; Teece et al., 2016). |

| Strategic Vision | Contributes to long-term planning and competitive advantage (Teece, 2014). |

| Market Sensing | Identifies trends, customer needs, and competitive dynamics (Teece, 2018b; Warner & Wäger, 2019). |

| Risk Management | Balances risk-taking and mitigation in uncertain contexts (Ambrosini & Bowman, 2009). |

| Routine and Adaptive Processes | Combines stability with adaptability to optimize performance (Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000). |

| Long-Term Orientation | Focuses on sustainable advantages rather than short-term gains (Teece et al., 1997). |

| Micro-Foundation | Traditional Approach | Strategic Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Sensing | Focus on compliance and immediate needs | Proactive market analysis and innovation |

| Seizing | Transactional decisions | Evidence-based, value-driven strategies |

| Transforming | Incremental process improvements | Organizational learning and transformation |

| Case Studies—Brief Description and Key Objectives | Six Focus Groups | 12 Semi-Structured Interviews |

|---|---|---|

| CCC1: This council spends over GBP 390 million annually, balancing budget cuts with increasing policy expectations. The focus is on strategic procurement and value creation in challenging financial contexts. | Procurement professionals (90 min) | Head of commissioning and procurement and three procurement managers (60 min each) |

| CCC2: Spending GBP 215 million annually, this council emphasizes strategic thinking and sustainability in procurement practices. | Audit and risk manager, category manager officer, and strategic procurement manager | Strategic procurement manager |

| MCC: This council focuses on integrating value into each stage of the procurement cycle, with GBP 98 million annual expenditure across diverse suppliers. | Procurement staff | Strategic procurement manager |

| CCBC: Spending GBP 251 million annually, this council aligns procurement with cultural, social, economic, and environmental objectives under the Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015. | Procurement staff | Head of procurement and two procurement managers |

| NCC: With annual spending of GBP 150 million, this council integrates social, economic, and environmental considerations into procurement. | Procurement staff | Strategic procurement manager |

| PCC: Spending GBP 250 million annually, this council emphasizes social value, local economic growth, and environmental sustainability. | Procurement staff | Lead procurement service, risk management manager, and strategic management manager |

| Interview Number/Date: | Interviewer: |

| Name of Participant: | Location: |

| Organisation: | Rank, Role or Title: |

| Interview Policy Review | |

| |

| Interview Questions | |

| Part One: Procurement Maturity Stage | |

| 1. What is the level of procurement involvement in the corporate strategy? | |

| 2. What is the scope of procurement activities? | |

| 3. What is your approach to relationship management? | |

| 4. In what extend technology has been involved in procurement? | |

| 5. What is the level of skills and knowledge of procurement professional? | |

| 6. What are key performance indicators | |

| 7. How visible is procurement on your organisation? | |

| Part Two: DCS—Sensing, Seizing and Transforming | |

Sensing:

| |

Seizing Procurement Opportunities:

| |

Transforming Procurement:

| |

| Is there anything else you would like to add? | |

| Interview Review | |

| |

| Participants Name: | |

| Interviewer Name: Signature: Date: | |

| P.S.: The information provided will be handled in strict accordance with the Data Protection Act, ensuring confidentiality and anonymity throughout the research process. Participants retain the right to withdraw from the study at any stage, and a Participant Withdrawal Form will be made available to facilitate this process. | |

| Aspect | Large Local Authorities | Small Local Authorities |

|---|---|---|

| Annual Procurement Expenditure | Higher budgets, e.g., CCC1 with over GBP 390 million annually. | Lower budgets, e.g., MCC with GBP 98 million annually. |

| Sensing Capabilities | Proactive market analysis and stakeholder engagement; restructuring around category management (CM) to align with strategic goals. | Limited capacity leading to reactive approaches; reliance on external initiatives and tools to promote compliance. |

| Seizing Capabilities | Ability to capitalize on opportunities through strategic partnerships and resource allocation; emphasis on value-for-money outcomes. | Operational focus with constraints in leveraging opportunities; emphasis on compliance and maintaining contract registers. |

| Transforming Capabilities | Strong leadership driving innovation and alignment with organizational objectives; proactive adaptation to budgetary constraints. | Challenges due to leadership turnover and resource limitations; efforts focused on maintaining existing processes with incremental improvements. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ndrecaj, V.; Tlemsani, I.; Mohamed Hashim, M.A. Unveiling Dynamic Capabilities in Public Procurement: Myths, Realities, and Strategic Transformation. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15040134

Ndrecaj V, Tlemsani I, Mohamed Hashim MA. Unveiling Dynamic Capabilities in Public Procurement: Myths, Realities, and Strategic Transformation. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(4):134. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15040134

Chicago/Turabian StyleNdrecaj, Vera, Issam Tlemsani, and Mohamed Ashmel Mohamed Hashim. 2025. "Unveiling Dynamic Capabilities in Public Procurement: Myths, Realities, and Strategic Transformation" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 4: 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15040134

APA StyleNdrecaj, V., Tlemsani, I., & Mohamed Hashim, M. A. (2025). Unveiling Dynamic Capabilities in Public Procurement: Myths, Realities, and Strategic Transformation. Administrative Sciences, 15(4), 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15040134