Impact of Leader Behavior on Employee Experience and Job Satisfaction in Educational Institutions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Leader Behavior and Job Satisfaction

2.2. The Initial Structure and the Employee Experience

2.3. Employee Consideration and Experience

2.4. Employee Experience and Job Satisfaction

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample and Procedure

3.2. Instrument

3.3. Data Analysis Procedure

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model Evaluation

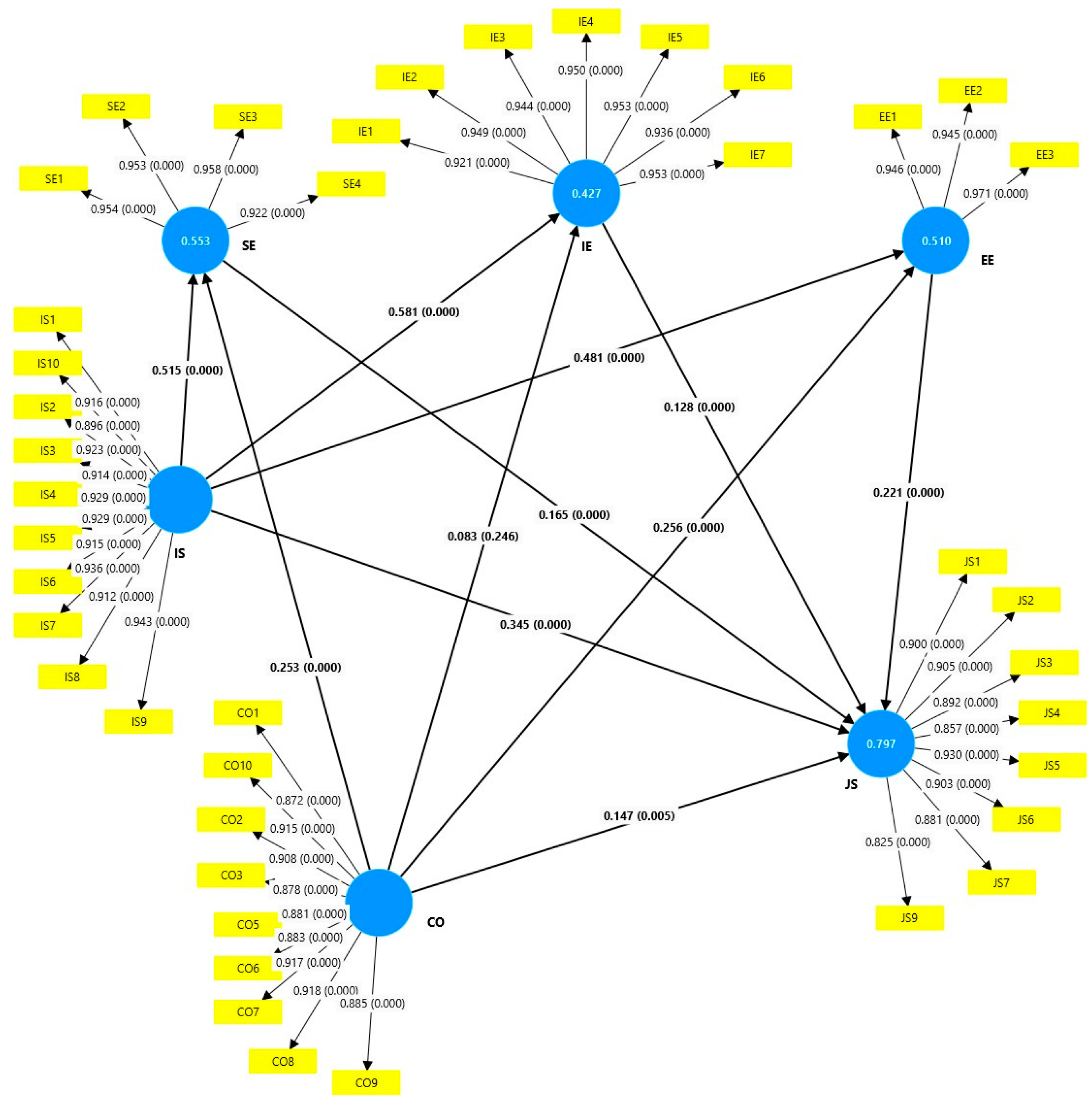

4.2. Structural Model Evaluation

5. Discussion

Theoretical and Practical Implications

6. Conclusions

6.1. Limitations of This Study

6.2. Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Acuña-Hurtado, N., García-Salirrosas, E. E., Villar-Guevara, M., & Fernández-Mallma, I. (2024). Scale to evaluate employee experience: Evidence of validity and reliability in regular basic education teachers in the Peruvian context. Behavioral Sciences, 14(8), 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agustin-Silvestre, J. A., Villar-Guevara, M., García-Salirrosas, E. E., & Fernández-Mallma, I. (2024). The human side of leadership: Exploring the impact of servant leadership on work happiness and organizational justice. Behavioral Sciences, 14(12), 1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcázar Cruz, P. (2020). Estilo de Liderazgo y Compromiso Organizacional: Impacto del liderazgo transformacional. Economía Coyuntural, 5(4), 89–122. [Google Scholar]

- Arviv Elyashiv, R., & Hanuka, G. (2024). Teachers’ job satisfaction: Religious and secular schools in Israel. British Journal of Religious Education, 46(4), 354–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balyer, A., & Oezcan, K. (2012). Cultural adaptation of headmasters’ transformational leadership scale and a study on teachers’ perceptions. Eurasian Journal of Educational Research, 49, 103–128. [Google Scholar]

- Barrué, P., & Sánchez-Gómez, M. (2021). La experiencia emocional de enfermeras de la Unidad de Hospitalización a Domicilio en cuidados paliativos: Un estudio cualitativo exploratorio. Enfermería Clínica, 31(4), 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, G.-W., Ng, W.-L., & Shin, Y. (2008). The effect of a perceived leader’s influence on the motivation of the members of nonwork-related virtual communities. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 55(2), 292–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H., Beck, S. L., & Amos, L. K. (2005). Leadership styles and nursing faculty job satisfaction in Taiwan. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 37(4), 374–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen de Lara, E., Lleó, Á., Domingo, V., & Torralba, J. M. (2024). Leadership as service: Developing a character education program for university students in Spain. International Journal of Ethics Education, 9, 209–227. [Google Scholar]

- De Los Heros Rondenil, M. G., Murillo López, S. C., & Solana Villanueva, N. (2020). Satisfacción laboral en tiempos de pandemia: El caso de docentes universitarios del área de salud. Revista de Economía Del Caribe, 26, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz Dumont, J. R., Ledesma Cuadros, M. J., Tito Cárdenas, J. V., & Carranza Haro, L. R. (2023). Satisfacción laboral: Algunas consideraciones. Revista Venezolana de Gerencia, 28(101), 158–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donawa Torres, Z. A. (2018). Percepción de la calidad de vida laboral en los empleados en las organizaciones. NOVUM, 2(8), 43–63. [Google Scholar]

- Durán, S. (2019). Gestión del conocimiento y satisfacción laboral en las instituciones educativas del nivel inicial. Revista Innova Educación, 1(3), 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza, O., González, L., Miranda, C., Sandoval, L., Corradi, B., McGinn, N., & Larrondo, Y. (2024). Job satisfaction among university graduates in Chile. Higher Education, Skills and Work-Based Learning, 14(4), 865–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Salirrosas, E. E., Rondon-Eusebio, R. F., Geraldo-Campos, L. A., & Acevedo-Duque, Á. (2023). Job satisfaction in remote work: The role of positive spillover from work to family and work–life balance. Behavioral Sciences, 13(11), 916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaudet, M.-C., & Tremblay, M. (2017). Initiating structure leadership and employee behaviors: The role of perceived organizational support, affective commitment and leader–member exchange. European Management Journal, 35(5), 663–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavilan, D., Avelló, M., & Fernández Lores, S. (2013). Employer branding: La experiencia de la marca empleadora y su efecto sobre el compromiso afectivo. ADResearch ESIC International Journal of Communication Research, 7(7), 58–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghamrawi, N., Abu-Shawish, R. K., Shal, T., & Ghamrawi, N. A. R. (2024). Teacher leadership in higher education: Why not? Cogent Education, 11(1), 2366679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Díaz, R. R., Acevedo-Duque, Á., Salazar-Sepúlveda, G., & Castillo, D. (2021). Contributions of subjective well-being and good living to the contemporary development of the notion of sustainable human development. Sustainability, 13(6), 3298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Bayona, L., Valencia-Arias, A., Orozco-Toro, J. A., Tabares-Penagos, A., & Moreno-López, G. (2024). Importance of relationship marketing in higher education management: The perspective of university teachers. Cogent Education, 11(1), 2332858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A Primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., Gudergan, S. P., Castillo Apraiz, J., Cepeda Carrión, G. A., & Roldán, J. L. (2019). Manual avanzado de Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). Omnia Science. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Hopkins, L., & Kuppelwieser, V. G. (2014). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. European Business Review, 26(2), 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J., Hollingsworth, C. L., Randolph, A. B., & Chong, A. Y. L. (2017). An updated and expanded assessment of PLS-SEM in information systems research. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 117(3), 442–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpin, A. W. (1955). The leader behavior and leadership ideology of educational administrators and aircraft commanders. Harvard Educational Review, 25, 18–32. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q., Davison, R. M., Liu, H., & Gu, J. (2008). The impact of leadership style on knowledge-sharing intentions in China. Journal of Global Information Management (JGIM), 16, 67–91. [Google Scholar]

- Hurtado Palomino, A., Dante De la Gala Velásquez, B. R., Ccorisapra Quintana, F. d. M., & Quispe Ambrocio, A. D. (2021). Organizational culture and commitment: Indirect effects of the employer brand experience. Revista Universidad y Sociedad, 13(4), 369–377. [Google Scholar]

- IESALC. (2024). CRES+5 Declaration: Commitment to democratisation and universalisation of higher education as an engine of development—CRES+5. Available online: https://cres2018mas5.org/en/conferencia-regional-de-educacion-superior-5-english/ (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- Jauregui-Arroyo, R. R., Goñi Avila, N. M., & Rondon-Jara, E. (2023). Estilos de liderazgo de los millennials y su influencia en el desempeño de las pequeñas empresas del sector textil manufactura. Innovar, 33(89), 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Bucarey, C., Acevedo-Duque, Á., Müller-Pérez, S., Aguilar-Gallardo, L., Mora-Moscoso, M., & Vargas, E. C. (2021). Student’s satisfaction of the quality of online learning in higher education: An empirical study. Sustainability, 13(21), 11960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, N. Y., Lee, K. C., Lee, D. S., & Hahn, M. (2015). Empirical analysis of roles of perceived leadership styles and trust on team members’ creativity: Evidence from Korean ICT companies. Computers in Human Behavior, 42, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T. A., Piccolo, R. F., & Ilies, R. (2004). The forgotten ones? The validity of consideration and initiating structure in leadership research. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(1), 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. (2015). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (4th ed.). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert, L. S., Tepper, B. J., Carr, J. C., Holt, D. T., & Barelka, A. J. (2012). Forgotten but not gone: An examination of fit between leader consideration and initiating structure needed and received. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(5), 913–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laura-Arias, E., Villar-Guevara, M., & Millones-Liza, D. Y. (2024). Servant leadership, brand love, and work ethic: Important predictors of general health in workers in the education sector. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1274965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z., Li, W., Fu, Y., Xu, Z., & Wang, F. (2024). Does consideration and initiating structure leadership help or hinder employees’ creativity? The role of psychological ownership and time availability. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 15(4), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L. H., Varty, C. T., Lian, H., Brown, D. J., Law, D., Chen, J., & Evans, R. (2023). Subordinate organizational citizenship behavior trajectories and well-being: The mediating roles of perceived supervisor consideration and initiating structure. Human Performance, 36(2), 64–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F. M. C. (2024). Scrutinizing job satisfaction during COVID-19 through Facebook. Translation Spaces, 13(1), 102–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macfarlane, B., Bolden, R., & Watermeyer, R. (2024). Three perspectives on leadership in higher education: Traditionalist, reformist, pragmatist. Higher Education, 88(4), 1381–1402. [Google Scholar]

- Manzini, J. L. (2000). Declaración de Helsinki: Principios éticos para la investigación médica sobre sujetos humanos. Acta Bioethica, 6(2), 321–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moldes Farelo, R., & Gómez, F. (2021). Hacia la construcción de un modelo de Liderazgo Intergeneracional. Revista Internacional de Organizaciones, 25–26, 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otzen, T., & Manterola, C. (2017). Técnicas de muestreo sobre una población a estudio. International Journal of Morphology, 35(1), 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prialé, M. A., Vera Ruiz, A., Espinosa, A., Kamiche Zegarra, J. N., Yepes López, G. A., Darmohraj, A. M., & Flores Venturi, C. I. (2024). Measurement of sustainable attitudes: A scale for business students. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puri, K., Suresh, K., Gogtay, N., & Thatte, U. (2009). Declaration of Helsinki, 2008. Journal of Postgraduate Medicine, 55(2), 131–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Lora, G. M., Rivero-Isla, J. C., & Lopez-Chavez, B. E. (2024). An analysis of the relationship between organisational resilience and Local Educational Management Units’ responses on education services delivery in Peru during the COVID-19 pandemic. Public Administration and Policy, 27(1), 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowold, J., Borgmann, L., & Bormann, K. (2014). Which leadership constructs are important for predicting job satisfaction, affective commitment, and perceived job performance in profit versus nonprofit organizations? Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 25(2), 147–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snell, R. S., Yi, Z., & Chak, A. M. K. (2013). Representational predicaments for employees: Their impact on perceptions of supervisors’ individualized consideration and on employee job satisfaction. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 24(8), 1646–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, M., Gaudet, M.-C., & Parent-Rocheleau, X. (2018). Good things are not eternal: How consideration leadership and initiating structure influence the dynamic nature of organizational justice and extra-role behaviors at the collective level. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 25(2), 211–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente Coronado, M. S., López Arroyo, P., Trejo Martín, C., & González Ballester, S. (2019). Satisfacción docente y su influencia en la satisfacción del alumnado. International Journal of Developmental and Educational Psychology. Revista INFAD de Psicología, 3(1), 37–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walumbwa, F. O., Hsu, I.-C., Wu, C., Misati, E., & Christensen-Salem, A. (2019). Employee service performance and collective turnover: Examining the influence of initiating structure leadership, service climate and meaningfulness. Human Relations, 72(7), 1131–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, J., Azar, A., & Flessa, J. (2018). An ineffective preparation? The scarce effect in primary school principals’ practices of school leadership preparation and training in seven countries in Latin America. Educational Management Administration and Leadership, 46(2), 226–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age range | 18–30 | 100 | 15.4 |

| 31–40 | 200 | 30.7 | |

| 41–50 | 234 | 35.9 | |

| 51–60 | 101 | 15.5 | |

| 61–70 | 16 | 2.5 | |

| Gender | Male | 239 | 36.7 |

| Female | 412 | 63.3 | |

| Educational level | Bachelor | 292 | 44.9 |

| Doctor | 3 | 0.5 | |

| Institute/Pedagogical | 200 | 30.7 | |

| Master | 156 | 24.0 | |

| Construct | Item | Loading | Alpha | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consideration (CO) | CO1 | 0.872 | 0.969 | 0.970 | 0.802 |

| CO2 | 0.908 | ||||

| CO3 | 0.878 | ||||

| CO5 | 0.881 | ||||

| CO6 | 0.883 | ||||

| CO7 | 0.917 | ||||

| CO8 | 0.918 | ||||

| CO9 | 0.885 | ||||

| CO10 | 0.915 | ||||

| Emotional experience (EE) | EE1 | 0.946 | 0.951 | 0.953 | 0.910 |

| EE2 | 0.945 | ||||

| EE3 | 0.971 | ||||

| Intellectual experience (IE) | IE1 | 0.921 | 0.980 | 0.980 | 0.891 |

| IE2 | 0.949 | ||||

| IE3 | 0.944 | ||||

| IE4 | 0.950 | ||||

| IE5 | 0.953 | ||||

| IE6 | 0.936 | ||||

| IE7 | 0.953 | ||||

| Initiating structure (IS) | IS1 | 0.916 | 0.980 | 0.980 | 0.849 |

| IS2 | 0.923 | ||||

| IS3 | 0.914 | ||||

| IS4 | 0.929 | ||||

| IS5 | 0.929 | ||||

| IS6 | 0.915 | ||||

| IS7 | 0.936 | ||||

| IS8 | 0.912 | ||||

| IS9 | 0.943 | ||||

| IS10 | 0.896 | ||||

| Job Satisfaction (JS) | JS1 | 0.900 | 0.961 | 0.963 | 0.787 |

| JS2 | 0.905 | ||||

| JS3 | 0.892 | ||||

| JS4 | 0.857 | ||||

| JS5 | 0.930 | ||||

| JS6 | 0.903 | ||||

| JS7 | 0.881 | ||||

| JS9 | 0.825 | ||||

| Sensory experience (SE) | SE1 | 0.954 | 0.961 | 0.962 | 0.896 |

| SE2 | 0.953 | ||||

| SE3 | 0.958 | ||||

| SE4 | 0.922 |

| CO | EE | IE | IS | JS | SE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consideration (CO) | 0.895 | |||||

| Emotional experience (EE) | 0.671 | 0.954 | ||||

| Intellectual experience (IE) | 0.583 | 0.693 | 0.944 | |||

| Initiating structure (IS) | 0.862 | 0.702 | 0.652 | 0.921 | ||

| Job Satisfaction (JS) | 0.782 | 0.784 | 0.711 | 0.831 | 0.887 | |

| Sensory experience (SE) | 0.697 | 0.809 | 0.723 | 0.733 | 0.791 | 0.947 |

| Construct | R2 |

|---|---|

| Sensory experience (SE) | 0.553 |

| Intellectual experience (IE) | 0.427 |

| Emotional experience (EE) | 0.510 |

| Job Satisfaction (JS) | 0.797 |

| H | Relationship | Original Sample (O) | Sample Mean (M) | Standard Deviation (STDEV) | T Statistics (|O/STDEV|) | p Values | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a | IS → JS | 0.345 | 0.348 | 0.059 | 5.844 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H1b | CO → JS | 0.147 | 0.147 | 0.052 | 2.830 | 0.005 | Accepted |

| H2a | IS → SE | 0.515 | 0.514 | 0.070 | 7.339 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H2b | IS → IE | 0.581 | 0.581 | 0.069 | 8.421 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H2c | IS → EE | 0.481 | 0.480 | 0.067 | 7.158 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H3a | CO → SE | 0.253 | 0.253 | 0.070 | 3.637 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H3b | CO → IE | 0.083 | 0.081 | 0.071 | 1.160 | 0.246 | Declined |

| H3c | CO → EE | 0.256 | 0.257 | 0.069 | 3.721 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H4a | SE → JS | 0.165 | 0.163 | 0.045 | 3.683 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H4b | IE → JS | 0.128 | 0.128 | 0.034 | 3.749 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H4c | EE → JS | 0.221 | 0.221 | 0.038 | 5.882 | 0.000 | Accepted |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

García-Salirrosas, E.E.; Yong-Chung, F.E.; Jauregui-Arroyo, R.R.; Escobar-Farfán, M.; Acevedo-Duque, Á. Impact of Leader Behavior on Employee Experience and Job Satisfaction in Educational Institutions. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 119. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15040119

García-Salirrosas EE, Yong-Chung FE, Jauregui-Arroyo RR, Escobar-Farfán M, Acevedo-Duque Á. Impact of Leader Behavior on Employee Experience and Job Satisfaction in Educational Institutions. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(4):119. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15040119

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarcía-Salirrosas, Elizabeth Emperatriz, Felipe Eduardo Yong-Chung, Ralphi Ricardo Jauregui-Arroyo, Manuel Escobar-Farfán, and Ángel Acevedo-Duque. 2025. "Impact of Leader Behavior on Employee Experience and Job Satisfaction in Educational Institutions" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 4: 119. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15040119

APA StyleGarcía-Salirrosas, E. E., Yong-Chung, F. E., Jauregui-Arroyo, R. R., Escobar-Farfán, M., & Acevedo-Duque, Á. (2025). Impact of Leader Behavior on Employee Experience and Job Satisfaction in Educational Institutions. Administrative Sciences, 15(4), 119. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15040119