Psychological Capital and Entrepreneurial Intention—The Mediation Role of Internet Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Conceptual Clarifications

2.2. Psychological Capital and Entrepreneurial Intention

2.3. Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy and Intention

2.4. Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy as Key Mediator

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants and Procedure

3.2. Ethical Considerations

3.3. Measures

3.4. Data Analysis Strategy

4. Results

4.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Sample

4.2. Common Method Bias (CMB) Assessment

4.3. Descriptive and Correlational Analysis

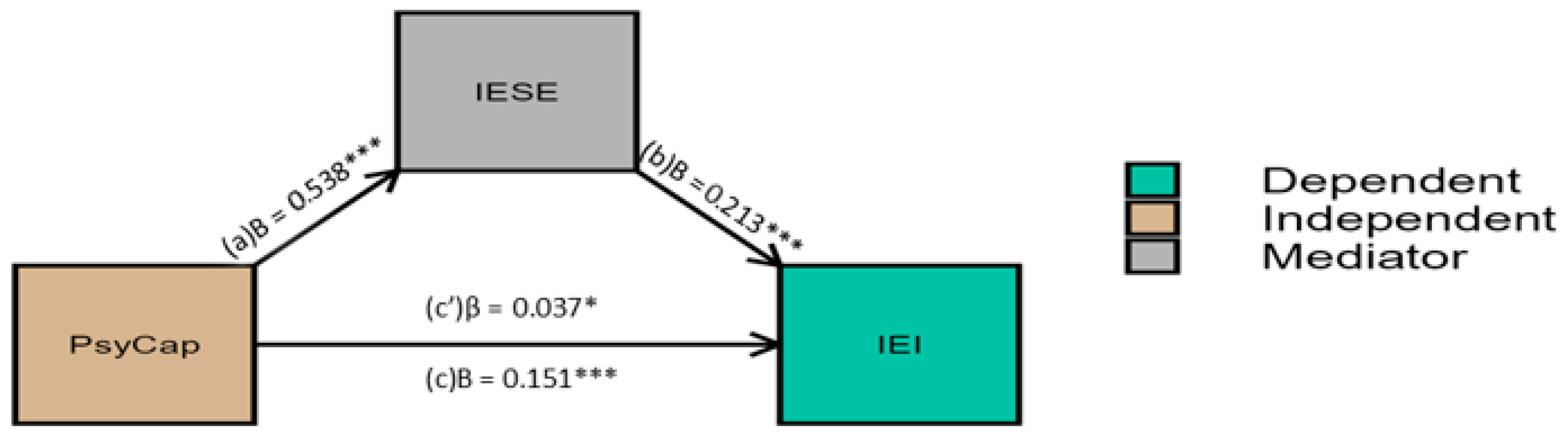

4.4. Analysis of Mediation Effects

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IESE | Internet entrepreneurial self-efficacy |

| IEI | Internet entrepreneurial intention |

| ESE | Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy |

| EI | Entrepreneurial Intention |

| PsyCap | Psychological capital |

| SCT | Social Cognitive Theory |

| EFA | Exploratory Factor Analysis |

| KMO | Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin |

| CFA | Confirmatory Factor Analysis |

| CFI | Comparative fit index |

| TLI | Tucker–Lewis index |

| NFI | Normed fit index |

| RMSEA | Root mean squared error of approximation |

| SRMR | Standardized root mean square residual |

| AVE | Average variance extracted |

| CR | Composite reliability |

References

- Al-Mamary, Y. H. (2025). The transformative power of artificial intelligence in entrepreneurship: Exploring AI’s capabilities for the success of entrepreneurial ventures. Future Business Journal, 11(1), 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Omoush, K. S. (2022). Understanding the impact of intellectual capital on e-business entrepreneurial orientation and competitive agility: An empirical study. Information Systems Frontiers, 24(2), 549–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qadasi, N., Zhang, G., Al-Awlaqi, M. A., Alshebami, A. S., & Aamer, A. M. (2023). Factors influencing entrepreneurial intention of university students in Yemen: The mediating role of entrepreneurial self-efficacy. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1111934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ardelean, B. O. (2021). Role of technological knowledge and entrepreneurial orientation on entrepreneurial success: A mediating role of psychological capital. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 814733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auer Antončič, J., Veselinovič, D., Antončič, B., Grbec, D. L., & Li, Z. (2021). Financial self-efficacy in family business environments. Journal of Enterprising Culture, 29(2), 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachmann, N., Rose, R., Maul, V., & Hölzle, K. (2024). What makes for future entrepreneurs? The role of digital competencies for entrepreneurial intention. Journal of Business Research, 174, 114481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balgiu, B. A., Cotoară, D. M., & Simionescu-Panait, A. (2024). Validation of the Internet Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy scale among Romanian technical students. PLoS ONE, 19(10), e0312929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W. H. Freeman. [Google Scholar]

- Barroso, M., & Laborda, J. (2022). Digital transformation and the emergence of the Fintech sector: Systematic literature review. Digital Business, 2, 100028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.-H., Shu, Y., Wang, C.-L., Chen, M.-Y., & Ho, W.-S. (2020). Cyber-entrepreneurship as an innovative orientation: Does positive thinking moderate the relationship between cyber-entrepreneurial self-efficacy and cyber-entrepreneurial intentions in non-IT students? Computers in Human Behavior, 107, 105975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compagnucci, L., & Spigarelli, F. (2020). The third mission of the university: A systematic literature review on potentials and constraints. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 161, 120284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharmanegara, I. B. A., Rahmayanti, P. L. D., & Yasa, N. N. K. (2022). The role of entrepreneurial self-efficacy in mediating the effect of entrepreneurship education and financial support on entrepreneurial behavior. International Journal of Social Science and Business, 6(2), 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dul, J. (2020). Necessary Condition Analysis (NCA): Logic and methodology of “necessary but not sufficient” causality. Organizational Research Methods, 23(4), 812–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, C. D., & Bernat, T. (2019, September 4–6). Entrepreneurial self-efficacy and intention among Vietnamese students: A meta-analytic path analysis based on the theory of planned behavior [Conference proceeding]. 23rd International Conference on Knowledge-Based and Intelligent Information & Engineering Systems (KES), Procedia Computer Science (Volume 159, pp. 2447–2460), Budapest, Hungary. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, C. M., Simmering, M. J., Atinc, G., Atinc, Y., & Babin, B. J. (2016). Common methods variance detection in business research. Journal of Business Research, 69(8), 3192–3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddoud, M. Y., Nowiński, W., Laouiti, R., & Onjewu, A.-K. E. (2024). Entrepreneurial implementation intention: The role of psychological capital and entrepreneurship education. The International Journal of Management Education, 22(2), 100982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2022). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (3rd ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A. F. (2022). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis (3rd ed.). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hazan Liran, B., & Miller, P. (2019). The role of psychological capital in academic adjustment among university students. Journal of Happiness Studies, 21(4), 1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kholifah, N., Nurtanto, M., Mutohhari, F., Majid, N. W. A., & Fawaid, M. (2024). The role of digital technology competency and psychological capital in vocational education students: The mediating role of entrepreneurial self-efficacy. Journal of Technical Education and Training, 16(2), 238–250. Available online: https://publisher.uthm.edu.my/ojs/index.php/JTET/article/view/15640 (accessed on 18 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. Y. (2013). Statistical notes for clinical researchers: Assessing normal distribution (2) using skewness and kurtosis. Restorative Dentistry & Endodontics, 38(1), 52–54. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3591587/ (accessed on 18 November 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kollmann, T., Kleine-Stegemann, L., Cruppe, K. D., & Then-Bergh, C. (2021). Eras of digital entrepreneurship. Business & Information Systems Engineering, 64(1), 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kun, D. (2025). The influence of entrepreneurial psychological capital on college students’ entrepreneurial intention and development strategies. Academic Journal of Business & Management, 6(12), 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X., Lin, C., Zhao, G., & Zhao, D. (2019). Research on the effects of entrepreneurial education and entrepreneurial self-efficacy on college students’ entrepreneurial intention. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupșa, D., & Vîrgă, D. (2020). Psychological capital questionnaire (PCQ): Analysis of the Romanian adaptation and validation. Psihologia Resurselor Umane, 16(1), 27–39. Available online: https://www.hrp-journal.com/index.php/pru/article/view/450 (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Luthans, F., Avolio, B. J., Avey, J. B., & Norman, S. M. (2007a). Positive psychological capital: Measurement and relationship with performance and satisfaction. Personnel Psychology, 60(3), 541–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F., Youssef, C., & Avolio, B. J. (2007b). Psychological capital: Developing the human competitive edge. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Maheshwari, G., & Kha, K. L. (2022). Investigating the relationship between educational support and entrepreneurial intention in Vietnam: The mediating role of entrepreneurial self-efficacy in the theory of planned behavior. International Journal of Management Education, 20(1), 100553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahfud, T., Hidayat, R. A., Thai, D., Kholifah, N., & Sari, A. I. (2024). Let’s be an entrepreneur through education! The role of entrepreneurial attitude orientation and psychological capital among university students. Global Business & Finance Review, 29(8), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahfud, T., Triyono, M. B., Sudira, P., & Mulyani, Y. (2020). The influence of social capital and entrepreneurial attitude orientation on entrepreneurial intentions: The mediating role of psychological capital. European Research on Management and Business Economics, 26(1), 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margaça, C., Sánchez García, J. C., & Hernández Sánchez, B. (2023). Psychological capital and entrepreneurship: A systematic literature review of a growing research agenda. Intangible Capital, 19(2), 276–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslakçı, A., Sürücü, L., & Şeşen, H. (2024). Positive psychological capital and university students’ entrepreneurial intentions: Does gender make a difference? International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 24(1), 125–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A., Obschonka, M., Schwarz, S., Cohen, M., & Nielsen, I. (2019). Entrepreneurial self-efficacy: A systematic review of the literature on its theoretical foundations, measurement, antecedents, and outcomes, and an agenda for future research. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 110, 403–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A., Ucbasaran, D., Zhu, F., & Hirst, G. (2014). Psychological capital: A review and synthesis. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 35(S1), 120–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, X. R. (2023). The relationship between psychological capital, entrepreneurial ability, and entrepreneurial performance of digital entrepreneurs. International Journal of Science and Business, 23(1), 106–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, A. (2024). Digital entrepreneurship. In Reference module in social sciences. Elsevier. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, V. H., Nguyen, T. K. C., Nguyen, T. B. L., Tran, T. T. T., & Nguyen, T. V. N. (2023). Subjective norms and entrepreneurial intention: A moderated-serial mediation model. Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Innovation, 19(1), 113–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primario, S., Rippa, P., & Secundo, G. (2022). Rethinking entrepreneurial education: The role of digital technologies to assess entrepreneurial self-efficacy and intention of STEM students. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 71(6), 2829–2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridwan, M., Fiodian, V. Y., Religia, Y., & Hardiana, S. R. (2024). Investigating the effect of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation in shaping digital entrepreneurial intention: The mediating role of self-efficacy. Asia Pacific Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 19(2), 190–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekhar, P., & Huang-Saad, A. (2021). Examining engineering students’ participation in entrepreneurship education programs: Implications for practice. International Journal of STEM Education, 8(40), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sooknannan, R., Coetzee, M., & Potgieter, I. L. (2024). Business innovation intent among college students: Contributions of psychological capital and entrepreneurial self-efficacy. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 34(5), 471–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tennakoon, N., Radulović, S., & Kyaruzi, I. S. (2024, October 25). The impact of digital education on the success of entrepreneurship: Exploring the interplay between online learning, digital self-efficacy, and entrepreneurial intention in the digital economy [Conference presentation]. 13th International Scientific Conference “Employment, Education and Entrepreneurship, Belgrade, Serbia. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, E. (2009). Individual entrepreneurial intent: Construct clarification and development of an internationally reliable metric. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(3), 669–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L. (2022). The influence of work values of college students on entrepreneurial intention: The moderating role of psychological capital. Frontiers in Education, 7, 1023537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, F. S., Leonard, K. M., & Srivastava, S. (2020). The role of psychological capital in entrepreneurial contexts. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 582133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vu, T. H., Do, A. D., Ha, D. L., Hoang, D. T., Le, T. A. V., & Le, T. T. H. (2024). Antecedents of digital entrepreneurial intention among engineering students. International Journal of Information Management Data Insights, 4(1), 100233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. S., Tseng, T.-H., Wang, Y.-M., & Chu, C.-W. (2020). Development and validation of an internet entrepreneurial self-efficacy scale. Internet Research, 30(2), 653–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardana, L. W., Martha, J. A., Wati, A. P., Narmaditya, B. S., Setyawati, A., Maula, F. I., Mahendra, A. M., & Suparno, S. (2024). Does entrepreneurial self-efficacy really matter for entrepreneurial intention? Lesson from COVID-19. Cogent Education, 11(1), 2317231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, C. H., Lin, H. H., Wang, Y. M., Wang, Y. S., & Lo, C. W. (2021). Investigating the relationships between entrepreneurial education and self-efficacy and performance in the context of internet entrepreneurship. The International Journal of Management Education, 19(3), 100565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, R., Chen, Y., & Zheng, Y. (2024). The impact of deep learning based-psychological capital with ideological and political education on entrepreneurial intentions. Scientific Report, 14, 18132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S. N., Li, Y. Q., Liu, C. H., & Ruan, W. Q. (2020). Critical factors identification and prediction of tourism and hospitality students’ entrepreneurial intention. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport & Tourism Education, 26, 100234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J., Wei, G., Chen, K. H., & Yien, J. M. (2020). Psychological capital and university students’ entrepreneurial intention in China: Mediation effect of entrepreneurial capitals. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhongnong, C. (2024). Entrepreneurship education, social network and entrepreneurial self-efficacy among Chinese college students. Asia Pacific Journal of Management and Sustainable Development, 12(1), 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Scales | χ2/df | CFI | TLI | NFI | RMSEA | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCQ | 3.16 | 0.956 | 0.949 | 0.938 | 0.049 | 0.039 |

| IESES | 4.50 | 0.951 | 0.952 | 0.946 | 0.063 | 0.051 |

| IEIS | 3.14 | 0.991 | 0.985 | 0.990 | 0.067 | 0.075 |

| Students | N = 900 |

|---|---|

| Sex | Males—57.77% |

| Females—42.23% | |

| Age | M = 21.06 years |

| Years of study | Early years—46.45% |

| Final years—53.55% | |

| Field of study | Information Technology & Communications—26.44% Medical Engineering—25% Transportation Studies—13.01% Business Engineering and Management—13.33% Civil Engineering—12% Electrical Engineering—10.22% |

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| PsyCap | – | ||

| IESE | 0.497 *** | – | |

| IEI | 0.333 *** | 0.544 *** | – |

| Mean | 3.812 | 4.712 | 3.606 |

| SD | 0.743 | 1.041 | 1.173 |

| Skewness | −0.112 | −0.108 | −0.093 |

| Kurtosis | −0.333 | −0.326 | −0.473 |

| α | 0.926 | 0.910 | 0.833 |

| ω | 0.929 | 0.912 | 0.834 |

| Direct Effect | Parameter Estimates (β) | SE | z-Values | 95%CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PsyCap → IESE | 0.538 | 0.031 | 17.400 | 0.477–0.598 | 0.001 |

| IESE → IEI | 0.213 | 0.014 | 15.648 | 0.186–0.238 | 0.001 |

| PsyCap → IEI | 0.037 | 0.015 | 2.513 | 0.008–0.065 | 0.012 |

| Indirect effect | |||||

| PsyCap → IESE → IEI | 0.114 | 0.010 | 11.635 | 0.095–0.134 | 0.001 |

| Total effect | |||||

| PsyCap → IEI | 0.151 | 0.014 | 10.616 | 0.123–0.179 | 0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Balgiu, B.A.; Mihai, P.; Chicioreanu, T.D. Psychological Capital and Entrepreneurial Intention—The Mediation Role of Internet Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 464. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15120464

Balgiu BA, Mihai P, Chicioreanu TD. Psychological Capital and Entrepreneurial Intention—The Mediation Role of Internet Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(12):464. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15120464

Chicago/Turabian StyleBalgiu, Beatrice Adriana, Petruța Mihai, and Teodora Daniela Chicioreanu. 2025. "Psychological Capital and Entrepreneurial Intention—The Mediation Role of Internet Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 12: 464. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15120464

APA StyleBalgiu, B. A., Mihai, P., & Chicioreanu, T. D. (2025). Psychological Capital and Entrepreneurial Intention—The Mediation Role of Internet Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy. Administrative Sciences, 15(12), 464. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15120464