Abstract

This article explores experts’ perspectives on the most important soft skills for entrepreneurial success in the Western Balkans (WB) and identifies effective educational and workplace practices to foster these skills. Using a qualitative Delphi study supported by a literature review, the research gathered and synthesized opinions from 20 experts representing Serbia, Albania, North Macedonia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina. Findings show that communication, adaptability, flexibility, teamwork, and critical thinking are essential for business success, while leadership, emotional intelligence, problem-solving, and teamwork are considered most vital for future entrepreneurs. Experts emphasized that group projects, specialized courses, and blended learning approaches are effective in educational settings, while workplace skill development benefits from training programs, mentoring, active communication, and openness to feedback. This study provides region-specific insights into skill-building strategies for young entrepreneurs, addressing a key research gap. By integrating expert consensus with evidence-based practices, the article offers a framework for educators, policymakers, institutions, and businesses to strengthen entrepreneurship education and workforce readiness across the WB region.

1. Introduction

In the last decade, research has been focused on finding the right combination of hard and soft skills for successful entrepreneurs and consequently their venture’s results (Dammert & Nansamba, 2023; Lavi et al., 2021). Hard skills are observed as technical skills related to the obtained knowledge and specific jobs, while soft skills are needed to implement acquired hard skills in everyday work activities successfully (Weber et al., 2011). Even though hard skills are a prerequisite for an effective entrepreneurial journey, extensive soft skills can improve business outcomes, such as sales and profitability. Furthermore, the entrepreneurs who receive training on soft skills, such as personal initiative and perseverance, are more likely to try to set themselves apart by implementing changes within their businesses, even though this training is not specifically focused on implementing business practices (Ubfal et al., 2022).

From the start of the transition to the present, the countries in the Western Balkans (WB) region have experienced significant changes in their general educational and vocational education training systems. However, the changes are rather slow and followed by a skilled people outflow to European Union countries (Ognjenović & Branković, 2013). On the other hand, research on people’s skill levels highlights that approximately one-third of employers in the WB region express dissatisfaction with the skills of recent graduates. Precisely, many employers identify significant gaps in graduates’ soft skills, such as decision-making, analytical abilities, teamwork, and planning and organizational skills. These skill deficiencies are often linked to traditional higher education systems that prioritize memorization over a student-centered learning approach (Bartlett & Uvalic, 2018). Consequently, a lack of soft skills hinders future entrepreneurs from starting their business.

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to explore and assess the critical role that soft skills development plays in preparing future entrepreneurs in the WB countries (Serbia, Albania, North Macedonia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina). Through the use of qualitative analysis of literature on soft skills and a Delphi study, the research task was to gather experts’ opinions and reach a consensus on the most essential soft skills for entrepreneurial success in this region. Additionally, the study aimed to identify effective educational and work practices that can enhance soft skills development within entrepreneurship education and work contexts, providing valuable insights for policymakers, educators, institutions, and business representatives in fostering entrepreneurial competencies of young people. Therefore, the experts in question were persons engaged in business activities, human resource managers, or successful entrepreneurs.

The paper reviews extensive international research on the role of soft skills in entrepreneurship. Studies from various researchers (Asbari et al., 2019; Balcar, 2016; Cimatti, 2016; Hendarman & Cantner, 2018; Polakova et al., 2023) emphasize that soft skills such as communication, teamwork, adaptability, leadership, and problem-solving are as crucial as hard skills for employability and entrepreneurial success. Prior work shows how these skills improve business outcomes (Dammert & Nansamba, 2023; Weber et al., 2011) and can be developed through active, experiential, and project-based learning approaches (Cinque, 2016; Lavi et al., 2021). Similar findings appear in workplace settings where mentoring, collaboration, and feedback foster these skills (Cimatti, 2016; Wilson et al., 2012). However, limited empirical attention has been given to transitional economies such as those of the WB, where the education systems, labor markets, and entrepreneurial ecosystems face distinct structural constraints. Existing regional reports primarily describe skills mismatches and labor market inefficiencies, but they do not identify which specific soft skills are most vital for entrepreneurship or how they can be effectively developed through education and workplace training in the WB (European Training Foundation, 2024; Gribben, 2018; Jandrić & Ranđelović, 2018). This study addresses this gap by offering systematic, expert-based insights into the prioritization and development of entrepreneurial soft skills within the WB context. As well, this study is the first to look into this subject with a group of experts from WB countries. The study’s innovation lies in its focus on the underexplored WB region, the application of the Delphi method to capture consensus among diverse experts from multiple countries, and the integration of educational and workplace dimensions to offer a holistic understanding of how soft skills for entrepreneurship can be effectively developed in this specific socio-economic context.

The study contributes to management and administrative practice by demonstrating how the development of entrepreneurial soft skills directly enhances organizational effectiveness, innovation, and employee performance. By identifying concrete educational and workplace strategies for cultivating these competencies, the findings provide actionable guidance for human resource managers and organizational leaders seeking to align training and development initiatives with strategic business goals. Furthermore, the study emphasizes that integrating soft skills development into human resource management practices can strengthen organizational culture, improve employee engagement, and foster a more adaptable and entrepreneurial workforce within the WB context and beyond.

After the introduction, a literature review on soft skills and their impact on entrepreneurial success will be presented. Moreover, educational and workplace approaches to soft skills development will be elaborated. As the methodology applied in the research, the Delphi study will be explained. Results derived from the Delphi study approach will be presented, followed by a discussion of similar results. Finally, implications for the education and business sectors and concluding remarks will be presented.

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Intersection Between Soft Skills and Entrepreneurship

The OECD Learning Compass 2030 identifies three clusters of skills: cognitive and meta-cognitive skills, social and emotional skills, and practical and physical skills (OECD, 2019, p. 4). Soft skills are observed as a complement to hard skills and as an integral component of an individual’s intelligence quotient. While hard skills are related to a specific job, soft skills can be applied in any position (Cimatti, 2016). Hence, there should be a balance, alignment, and unity between hard and soft skills. Soft skills might also be referred to as non-technical skills, which are unquestionably just as important as academic skills (Asbari et al., 2019). Even though soft skills cannot replace technical skills, the person can be upskilled in the technical domain by adding a soft skills component (Cacciolatti et al., 2017). Soft skills are a collection of dispositions and actions that transcend knowledge, such as proactiveness and perseverance (Ubfal et al., 2022, p. 2). According to Avença et al. (2024), the soft skills concept includes four elements: teambuilding, problem-solving, and leadership skills. There is also an opinion that soft skills incorporate non-academic skills such as communicativeness, critical thinking and problem-solving, teamwork, lifelong learning and information, ethics and professional morals, leadership, and entrepreneurial skills (Lavi et al., 2021; Ngang et al., 2015). In the research of Hendarman and Cantner (2018), relationship building and maintenance, tolerance for uncertainty, passion and optimism, and innovative leadership skills were classified as soft skills.

Also discussed as transversal, soft skills include a set of interpersonal skills that enable effective collaboration with people in the organization, as well as intrapersonal skills related to cognitive and self-management abilities (Botke et al., 2018; Cimatti, 2016; Strampe & Rambe, 2024). They are more closely related to cognitive skills than to non-cognitive skills (Balcar, 2016). “Soft skills are largely intangible, not associated with a deliverable or a real output, and they are employed without the use of tools or templates” (Hendarman & Cantner, 2018, p. 142). These skills are viewed as crucial for adaptability and flexibility in the workforce, especially in the context of the evolving demands of Industry 5.0, which is marked as being more human-centered compared to Industry 4.0 (Polakova et al., 2023). The significance of soft skills in contributing to wage increases was found to be comparable to that of hard skills, underscoring the critical importance of both skill sets for employees (Balcar, 2016). Furthermore, soft skills are mapped as an integral part of graduates’ 21st-century skills together with domain-general and STEM-specific skills (Lavi et al., 2021). These skills are frequently utilized in the pursuit of securing specific jobs or positions in the service industry (Cacciolatti et al., 2017), while they are also identified as predictors of personal productivity (Balcar, 2016). They are also an important factor for predicting entrepreneurial intentions, even more than entrepreneurial education (Pebrianto & Puspitowati, 2022). While technical skills are important, soft skills significantly contribute to an entrepreneur’s ability to succeed and sustain their business in a competitive environment. They enhance entrepreneurs’ interaction with the customer, problem-solving competence in unexpected challenges, team management for a cohesive work environment, networking and partnerships, innovation and creativity, and resilience (Dammert & Nansamba, 2023). Three key soft skills were identified—communication, leadership, and critical thinking/problem-solving—as vital for entrepreneurs’ success. These skills not only help entrepreneurs improve their competitiveness and productivity but also enable them to effectively connect with customers and motivate their employees (Tem et al., 2020).

According to the literature review provided, the following research questions are proposed:

- RQ1: What soft skills are desirable in modern business conditions?

- RQ2: What soft skills do experts find to be most crucial for future entrepreneurs?

2.2. Educational and Workplace Approaches to Soft Skills Development

The soft skills development process can be approached not only through education but also through workplace activities. Although there are several methods for soft skills development through the education process, the workplace methods are rather unknown or vague. The role of education in the development of soft skills is highlighted as critical (Lavi et al., 2021; Polakova et al., 2023), but cooperation between educational institutions, employers, and policymakers can also be beneficial (Cacciolatti et al., 2017) since educational programs for soft skills development are mostly sporadic (Balcar, 2016).

The development of soft skills occurs at educational institutions through a range of formal, nonformal, and informal activities. These activities can be categorized into four main types according to Cinque (2016): (1) accredited soft skills courses offered by universities or conducted within halls of residence by educators and tutors; (2) formally recognized soft skills courses organized within halls of residence; (3) non-recognized soft skills courses hosted in halls of residence; and (4) experiential learning opportunities, which involve the practical application of soft skills through hands-on activities. These typologies outline the varied approaches to cultivating soft skills. Educational institutions, including schools and universities, are seen as pivotal in fostering these skills through various learning methods such as active learning, e-learning, and experiential learning. It is recognized that secondary schools, vocational education institutions, and universities must adapt to the evolving educational needs, ensuring that graduates are equipped with essential soft skills such as teamwork, communication, collaboration, leadership, critical thinking, problem-solving, and creativity, which are increasingly demanded in the 21st-century workplace (Polakova et al., 2023). Integrating creative problem-solving and design thinking into educational curricula fosters the development of essential soft skills in students and learners. Problem-solving, in particular, stands out as a crucial cognitive and interpersonal skill, central to effective learning and professional development (Amalu et al., 2023).

When it comes to education, there are various approaches to enhancing students’ soft skills (Asbari et al., 2019; Lavi et al., 2021). Passive teaching and learning methods showed no effect on the development of soft skills, while active methods did. Active learning methods such as project-based learning, assignments, research, and laboratory tasks encourage students to interact with one another and reflect on their learning experiences, which is crucial for developing soft skills (Lavi et al., 2021). On the other hand, an experiential learning model (i.e., engagement in real-world scenarios, experience reflection, and feedback on actions and outcomes) appeared as one that can improve students’ soft skills for entrepreneurship by actively engaging them in the learning process. Soft skills that can be developed in such a learning process are confidence, risk-taking, leadership, originality, future orientation, teamwork, and communication skills (Asbari et al., 2019). The research of Salceanu et al. (2021) showed that through entrepreneurial and psychological programs for students, only communication and leadership skills as soft skill categories can be developed. The participants in the study of Tem et al. (2020) agreed that higher education institutions should prioritize teaching soft skills to prepare students for successful entrepreneurial careers. Overall, their findings suggest that soft skills are malleable and can be developed through structured training programs, which can ultimately contribute to reducing youth unemployment and driving economic growth.

On the other hand, work practices and on-the-job experience can additionally strengthen people’s soft skills. Research has shown that students lack soft skills when they exit the educational process (Sharvari, 2019; Wilson et al., 2012). On-the-job training for communication and leadership skills, mentorship programs in real work situations, collaborative projects that encourage teamwork, feedback mechanisms, and cultural awareness training are examples of how soft skills can be developed in the work environment (Cimatti, 2016).

The training offered by academia fails to match labor market needs for communication skills, leadership abilities, and critical thinking and problem-solving, which are recognized as significant deficiencies among graduates, hindering their employability (Cacciolatti et al., 2017; Wilson et al., 2012). Employers seek employees with critical and analytical thinking skills, effective interpersonal communication, and teamwork (Cacciolatti et al., 2017). Visits, internships, joint programs, laboratory experiences, and project-based activities organized in cooperation between educational institutions and employers have proven to be highly effective in enhancing students’ soft skills (Cimatti, 2016). In some cases, soft skills development strategies include both education activities at academic institutions and training at the companies’ premises (Cinque, 2016; Doerr & Novella, 2024).

Consequently, it has been proposed that establishing collaborative partnerships between entrepreneurial ventures and educational institutions is essential for fostering targeted soft skills development for innovative financing, venture creation, and venture growth, thereby enhancing the entrepreneurial readiness and behavior of a student as a nascent entrepreneur (Strampe & Rambe, 2024). If university programs fail to provide students and potential employees with such skills solely, employers are left to develop them through their practices. Therefore, there is a paramount need to develop soft skills through cooperation between educational institutions, employers, and colleagues met during this process.

According to the literature review provided, the following research questions are proposed:

- RQ3: What are the most effective methods for developing soft skills within formal educational systems?

- RQ4: What are the most effective methods for developing soft skills within workplace training programs?

2.3. Integration of Soft Skills’ Contextual Relevance to the Western Balkans

The International Labour Organization (ILO) has mapped self-employed, micro-enterprises, and SMEs as crucial employers in 99 countries, since more than 70 percent of the workforce is engaged in these enterprises (ILO, 2019). Therefore, the ILO launched training programs such as the Start and Improve Your Business program to boost entrepreneurs’ skills in various areas and increase the survival rate and growth of newly established enterprises (Dammert & Nansamba, 2023; ILO, 2019). This type of help for entrepreneurs is more than necessary. For example, South and Southeastern European countries, where WB countries such as Serbia are grouped, are ranked the lowest in terms of adaptability and employability skills. These countries generally have very low levels of workforce adaptability, indicating a need for significant improvements in their education systems and labor market policies (Jandrić & Ranđelović, 2018).

Moreover, the main challenges faced by youth entrepreneurs in the WB include high unemployment rates, inefficient policy frameworks, a lack of support services such as training and mentoring, access to finance, and undefined categories of young entrepreneurs (Gribben, 2018). Youth in Serbia, Albania, North Macedonia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina face rooted socio-economic barriers that compound education-to-work transitions. For example, youth unemployment in the region remains extraordinarily high, averaging 35% in Bosnia and Herzegovina and 25% in Serbia in 2022 (World Bank Group & Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies, 2024). OECD reviews note that although the WB has made progress in education, the region still lags behind OECD countries. Furthermore, the advancements achieved prior to the pandemic were hindered, with a significant decline in proficiency levels observed in the 2022 PISA assessment (UNICEF, 2024). Nevertheless, demand for soft skills such as managerial abilities, interpersonal skills, and teamwork in the WB countries has been pronounced in the recent period (World Bank Group, 2024). On the other hand, policy support in the form of career counseling, mentorship, and effective school-to-work transition programs is weak or inconsistent in the region, leaving youth without guidance (European Training Foundation, 2021). Countries such as Bosnia and Herzegovina and Serbia have a lack of young people but a higher number of elderly people, thus indicating a future shortage of young and skilled employees. Comparing Serbia, Albania, North Macedonia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina, Albania has the highest percentage of young people not in education, employment, or training, while Bosnia and Herzegovina, of all four countries, has the lowest percentage of people in upper secondary and tertiary education. In terms of the system performance index level that quantifies the provision of skills and competencies, of the four WB countries, Serbia is leading, followed by North Macedonia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Albania. Also, unemployed people in Serbia and North Macedonia are interested in training activities, subsidized employment, or self-employment measures, while in Albania, training and job creation, and in Bosnia and Herzegovina, employment and start-up incentives, are expected from public employment agencies at the national level (European Training Foundation, 2024). In short, systemic issues like limited adult guidance, underperformance in education compared to advanced countries, and volatile labor markets dominate the WB context. These contextual realities are rarely reflected in existing soft skills theory. For instance, analyses of the WB highlight that students’ “insufficiently developed soft skills” exacerbate school-to-work challenges (European Training Foundation, 2021).

Except for learner and program-design factors, where acquisition of hard and soft skills is placed, youth entrepreneurship and formal employment also depend on contextual factors. Hence, educational and training programs focused on entrepreneurship should be fine-tuned according to the regulations, economic situation, and social environment of a country or area, such as the WB region (Wiger et al., 2015). Since WB countries bear similar inheritance from the previous period, employers in the WB region believe that by updating teaching methods, such as switching from large lecture halls to smaller, interactive classrooms and substituting hands-on problem-solving techniques for purely theoretical instruction, educational institutions could better encourage the development of soft skills (Bartlett & Uvalic, 2018). The offer of educational programs and learning opportunities for skills development should be based on the common regional challenges, targeted at attracting entrepreneurial education (Vutsova et al., 2023), and aligned with the labor market needs.

Thus, a theoretical gap exists, as global soft skills models often underemphasize the impact of local education and labor market conditions documented above. This study addresses that gap by employing an expert consensus method, the Delphi study, to identify the soft skills most important for entrepreneurs in the WB context and to explore effective approaches for their development. In doing so, it explicitly links the region’s socio-economic challenges to soft skills theory, demonstrating how contextual factors shape soft skills priorities in these countries.

3. Methodology

3.1. Study Design

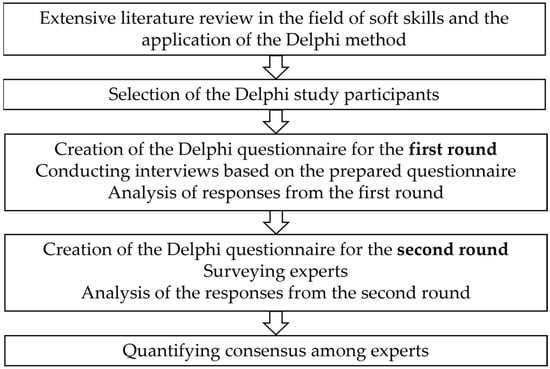

The goal of conducting the Delphi study is to gain a deeper insight into the necessary soft skills of young people and to encourage the development of these skills, which will make it easier for young people to successfully enter the work sphere by getting a job or starting their own business. Since the Delphi study is based on achieving consensus on effective practices and pinpointing areas of divergence, it forms a solid ground for the identification of best practices for youth soft skills development. It requires specification of the number of iterative processes or rounds, experts’ selection, design of procedures to conduct the study and collect answers, and selection of analytical methods that will be used to reach the consensus of experts’ opinion (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Delphi study flow. Source: authors.

This technique is mostly applied in entrepreneurial education research due to its benefits, such as obtaining consensus between experts that can lead to collective opinion in decision-making, diversity of experts consulted, and a flexible and systematic approach to complex topics (Hardie et al., 2023). The Delphi method is considered useful for the following scenarios (Linstone & Turoff, 2002; Okoli & Pawlowski, 2004):

- Investigation of complex issues that analytical methods cannot handle and when subjective opinions of experts are required;

- Situations requiring different types of knowledge and expertise due to the complexity of the observed problem, or where heterogeneity of individual opinions is necessary without requiring physical meetings of experts (consequently avoiding the halo effect);

- Structured but flexible research design and communication.

The method was developed by Dalkey and Helmer (1963) as a consensus-building tool through the iterative process of questioning and feedback that allows for the convergence of individual estimates, even when initial opinions are widely divergent. The first Delphi method that appeared in the forecasting study was one written by Gordon and Helmer in 1964. The purpose of this study was to obtain the most reliable consensus opinion from a group of experts (Marchau & van de Linde, 2016). The Delphi method refines expert analysis, accounts for uncertainties in predictions, and provides preliminary insights in the absence of empirical data.

Even though it was initially applied for forecasting developments based on experts’ opinions, nowadays, the usage of this method is not limited to forecasting and is not limited to the opinions of experts only. Today, the Delphi method is also used for providing group opinion in a controlled and systematic way (Marchau & van de Linde, 2016). While not without limitations, its adaptability and potential for methodological improvement make it a reliable alternative for decision-making in contexts reliant on expert opinion.

Researchers realize Delphi studies are conducted in a similar way, but certain consistent criteria apply to all qualitative Delphi studies, including purposive sampling, emergent design, anonymous and structured communication between participants, and thematic analysis (Brady, 2015, p. 3). In the current study, to reach the content validation, two rounds of data collection were conducted by using the protocol or Delphi questionnaire developed for this purpose. During the first Delphi round, participants were provided with brief, literature-based descriptions of each soft skill category to ensure a consistent understanding of the concepts discussed during the study. After the first round of the Delphi study was conducted in the form of an interview with open-ended questions, the questionnaire was re-evaluated using statements of experts that were common for the majority of them, thus preparing a closed-ended survey for the second round. In the second round of the Delphi study, a general agreement of experts was reached. This was the first stage of validation. The second stage of validation should be provided by using a final questionnaire to evaluate the importance of certain skills and the application of the observed practices in companies.

3.2. Participants

The process of selecting experts for a Delphi study primarily involves determining the criteria for experts and the number of experts. The criteria primarily pertain to years of experience in the research field and an understanding of the research topic. The criteria that selected experts have met were a minimum of higher education, a management position in the organization, a minimum of five years of work experience in general, a minimum of two years of experience in human resources management, or a minimum of 3 years of experience in running their own business. The authors applied a purposive sampling technique for expert recruitment and selection. In this way, selected experts met the minimum requirements for assessing the importance of soft skills and identifying ways to enrich them through education and work practices. Their first-hand understanding of skill gaps among employees and new graduates provides valuable insights into the effectiveness of different learning methods for soft skills development. Therefore, this research is mainly practice-based because this analysis evaluates the effectiveness of educational methods primarily from the labor market perspective and is grounded in employers’ observations of how these approaches translate into workplace outcomes.

The number of expert participants is not defined or standardized, and it can range between 5 and 100 participants (Avella, 2016; Gebrye et al., 2024; Okoli & Pawlowski, 2004). Delphi study participants can be grouped into homogeneous or heterogeneous panels. For homogeneous panels, according to some authors (de Villiers et al., 2005), 15 to 30 experts are sufficient, while for heterogeneous panels, the number of participants ranges from 5 to 10 experts per group.

This study’s panel was heterogeneous, consisting of two groups of experts (experts in human resource management and successful entrepreneurs) from four countries. Moreover, the minimum target number of questioned experts was 5 per country or 20 in total for Serbia, Albania, North Macedonia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina (WB countries). The whole group included nine experts in the field of human resource management and eleven entrepreneurs. Moreover, the study sample encompassed heads of human resource management departments, business owners, and top management representatives. The Delphi study includes experts from a very broad spectrum of industries, such as HRM, entrepreneurship support, banking, automotive, IT/tech, transport, textile, insurance, digital marketing, fashion, construction, university and research, communications, and PR. This diversity strengthens the credibility of your Delphi study, illustrating real multidisciplinary representation. Twelve experts were male, and eight were female. Twenty experts, divided into four panels, were recruited and selected for the Delphi study following the proposed criteria. The targeted number of participants was defined following previous studies conducted using this method (Gebrye et al., 2024; Okoli & Pawlowski, 2004). All experts participating in the Delphi study provided informed consent, agreeing to use and disclose data obtained through the research process, except for their identity.

3.3. Data Collection and Validity Criteria

The Delphi study usually includes two or three rounds, starting with open or semi-open questions for gathering data from the experts in the field in the first round and offering closed questions with proposed options (variables, statements) for their evaluation by the same experts in the second/third round. The questions in the first round are based on the literature review, while options for those questions in the second/third round are based on the experts’ answers during the first round. The last part of the Delphi study assumes reaching a consensus by validating experts’ answers from the last round (Brady, 2015; Haven et al., 2020). Following the procedure applied by Gebrye et al. (2024) and based on similar research conducted in the social sciences, in this research, the two-round Delphi method was applied (Fink-Hafner et al., 2019). The Delphi study experts were first contacted face-to-face, via telephone, or in some form of online video streaming communication by the researchers in every WB country during November 2023, forming in that way a multinational pool of experts from the WB region. After agreeing to take part in the research, the first round of the Delphi study was introduced. Experts were asked to answer questions in the form of an interview. Questions were previously developed according to the comprehensive literature review on soft skills and entrepreneurship. The estimated duration of the conversation with each expert was 15 min. After receiving the answers given by the respondents in narrative form, their summarization was the next step. Two researchers independently conducted a thematic summarization of answers to identify recurring concepts and merge overlapping statements. All experts’ answers were listed with the number of citations, thus making a summarized list of 4–6 answers per question as previously agreed upon by the research team (Table 1). To qualify for the group of the key ones, the answer should be proposed by over 50% of experts (Okoli & Pawlowski, 2004). Differences in interpretation were discussed until full consensus between the two researchers was achieved, ensuring the reliability of the summarized results. The summary of the answers was the basis for creating a questionnaire for experts for the second round of the Delphi study.

Table 1.

List of questions and experts’ answers for the first round of the Delphi study.

The same experts were surveyed in the second round of the research. Usually, this type of Delphi is named “e-Delphi” (Hunter et al., 2022). The second round moved into the quantitative domain; a questionnaire was devised based on the experts’ statements. They were invited to indicate a level of agreement with the importance of the statements (Daniels, 2017). To indicate the importance, in this case, a five-point Likert scale was used, where 1 represents “insignificant” and 5 represents “very significant”.

After the second round of the Delphi study, content validation was performed to obtain a quantified consensus regarding the statements/variables that should be included in the questionnaire as a tool for further soft skills research. Certain statistical tools, such as content validation ratio, relative participation of assessed values, and arithmetic mean, were used as content validation indicators.

The content validity ratio (CVR) proposed by Lawshe (1975) represents one of the quantitative methods in the content validity assessment (Hassan et al., 2022; Muktar & Mohd Matore, 2021; Samad et al., 2023). It is a linear transformation of a proportional level of agreement on how many experts within a panel rate a statement/variable as essential and is calculated in the following way (Ayre & Scally, 2014; Tiwari et al., 2024):

where

The variable relevance for this research is based on three criteria: (1) the arithmetic mean is greater than 3.5; (2) the relative participation of answers marked as significant (S)—4 and very significant (VS)—5 is higher than 0.5; (3) CVR is higher than the proposed value for 20 Delphi study participants, which is equal to 0.500 (Ayre & Scally, 2014). After two rounds of interviews surveying 20 experts in human resource management and entrepreneurs from the WB context, the common attitude was captured when all three criteria were fulfilled.

| —the content validity ratio; | |

| —number of experts indicating a statement/variable as essential (evaluated with marks 4 or 5); | |

| —the number of experts. |

4. Results

Soft skills are recognized for their transferability across various occupations, allowing individuals to adapt to changes and engage in lifelong learning, which is increasingly important in a technology-driven environment. Gathering data on soft skills and ways of their development was led by four research questions.

4.1. Research Question 1

RQ1: What soft skills are desirable in modern business conditions?

In round one, experts from the WB context stated that they believe soft skills desirable in modern conditions are communication skills, adaptability and flexibility, emotional intelligence, teamwork and collaboration, critical thinking, problem-solving, and time and conflict management. Some of the obtained answers were as follows:

Expert 1: “Communication skills (assertive communication), coping skills and a healthy response to stress, teamwork, people management skills, organizational skills (setting priorities, effective time management, etc.…), a certain level of flexibility in dealing with different situations, managing and resolving conflicts, focus on solving problems (“problem-solving”).”

Expert 2: “… it’s important for individuals to have the ability to adapt to different individuals and situations. Additionally, teamwork and emotional intelligence are crucial elements. Other necessary qualities in the modern business environment, in my opinion, would be effective communication skills, efficient time and conflict management, creativity, work ethics, and critical thinking.”

After receiving answers from round one, communication skills, adaptability and flexibility, emotional intelligence, teamwork and collaboration, and critical thinking were extracted as the most frequently occurring skills (Table 1). In round two, the same group of experts completed the survey, and a consensus was made that soft skills needed for modern business conditions are communication skills, adaptability and flexibility, teamwork and cooperation, and critical thinking (Table 2). Even though emotional intelligence enhances workplace performance by enabling individuals to navigate complex interpersonal dynamics, foster a collaborative culture, and manage conflicts constructively, Delphi study participants found it less important than other soft skills in a contemporary business environment.

Table 2.

Consensus validation criteria for the second round of the Delphi study.

4.2. Research Question 2

RQ2: What soft skills do experts find to be most crucial for future entrepreneurs?

In round one, experts from the WB context jointly highlighted that creativity, innovativeness, leadership skills, communication skills, risk-taking, flexibility, emotional intelligence, problem-solving skills, and teamwork stand out as the most important soft skills. Examples of experts’ opinions are presented below:

Expert 1: “Highly developed communication skills, active listening, positive attitude—open-minded, readiness for action, learning from own mistakes (lots of attempts), persistence, empathy, leadership.”

Expert 2: “Communication skills, creativity, innovation, critical thinking, problem-solving, organizational skills/time management, leadership skills, flexibility/adaptability.”

Analysis of results from round one provided output in the form of survey questions with offered options for leadership skills, communication skills, emotional intelligence, problem-solving skills, and teamwork (Table 1). After round two, responders reached consensus on all mentioned skills, thus establishing them as crucial for founding an entrepreneurial venture (Table 2).

4.3. Research Question 3

RQ3: What are the most effective methods for teaching soft skills within formal education systems?

When asked in which ways the formal education system builds or upskills individuals’ soft skills, in round one, the panel of experts responded that the education system should conduct activities such as encouragement of group projects, organization of special courses and training programs, encouragement of workshops, combining typical classroom learning/training programs, internships, guest lectures, debates or motivation of assertive communication. Some of the answers are presented as follows:

Expert 1: “In the formal education system students should be provided with real-world, hands-on experiences that simulate workplace scenarios. Internships, or community service projects can expose students to practical challenges, allowing them to apply and develop soft skills in a supportive learning environment.”

Expert 2: “In school, the teaching of soft skills should be emphasized in theoretical and academic aspects, but also by offering students participation in the workshops, internships, through non-academic lecturers invited to the auditorium to offer their experience.”

In round one, the most frequent answers of experts concerning educational activities aimed at upskilling soft skills are group projects, special courses, training programs, workshops, a combination of typical classroom learning/training programs, and assertive communication (Table 1). In round two, experts have not reached a consensus concerning workshops and assertive communication as effective methods for teaching soft skills in formal education systems (Table 2). Even though these activities are beneficial in most cases, experts expressed their opinion that these methods lack the necessary depth and contextual integration to effectively develop such soft skills within an educational context.

4.4. Research Question 4

RQ4: What are the most effective methods for teaching soft skills within workplace training programs?

When asked to state in which way it is possible to build soft skills within a work environment, in round one experts consider that through an interview, employee evaluation, task assignments, team tasks, special courses, training programs, mentoring one-on-one or in groups, active communication and by being receptive to employees’ feedback, organizations can work on soft skills’ building and strengthening at the workplace. Examples of answers are provided below:

Expert 1: “…in the workplace training and development programs, mentorship and coaching, performance feedback, cross-functional collaboration, positive organizational culture.”

Expert 2: “At work students can be taught through work experiences, trainings, workshops, staff team building and retreats etc.”

After round one, the frequencies of answers were calculated, and the following workplace training programs were identified: interviews, special courses, training programs, mentoring one-on-one or in groups, active communication, and being receptive to employees’ feedback (Table 1). In round two of the Delphi study, the interview occurred as the method on which experts did not reach a consensus (Table 1). Due to the interview’s limited capacity to provide hands-on practice or real-time feedback essential for developing such skills, experts declared it is not an important method of teaching soft skills in the working environment.

A summarized list of experts’ answers after round one of the Delphi study is presented below (Table 1).

Based on the different criteria, the obtained second-round Delphi study results were rather uniform, and the consensus between respondents was achieved for most of the variables. Hence, through assessment of quantitative data obtained in round two of the Delphi study, answers with low rates of the observed measures were excluded (Table 2). In Table 2, consensus validation criteria were calculated, and the results of experts’ answers after round two of the Delphi study are presented below. Variables/statements that did not compile to the validation criteria are highlighted.

Following the criteria of Ayre and Scally (2014), where the arithmetic mean is greater than 3.5 (column “mean”), the relative participation of answers marked as significant (S)—4 and very significant (VS)—5 on the Likert scale is higher than 0.5 (column relative “S” or “VS” answers), and the CVR is higher than the proposed value for 20 Delphi study participants, which is equal to 0.500 (column “CVR calculated”), Table 2 highlights the soft skills and their development methods that did not meet the proposed threshold. For example, emotional intelligence is excluded from soft skills because its CVR value is less than 0.5 as a threshold. In the case of ways for soft skill building and strengthening in the formal education system, encouraging workshops has a CVR of 0.2 (less than the threshold of 0.5), and assertive communication has both a CVR equal to 0 (less than the threshold of 0.5) and a relative number of “S” or “VS” answers equal to 0.5 (equal to the threshold of 0.5). Lastly, an interview, as a way of building soft skills in the workplace, did not meet all three criteria. Although several elements, such as emotional intelligence, encouraging workshops, assertive communication, and interview-based assessment, were initially considered, they were excluded from the final model because their importance thresholds fell below the predefined numerical cut-off. This indicates that, within the sample, these components did not contribute sufficiently to differentiating soft skills (e.g., emotional intelligence) and the effectiveness of the training programs (i.e., encouraging workshops, assertive communication, and interview-based assessment). Their exclusion suggests that the most influential factors are concentrated in the remaining variables, which therefore carry the primary explanatory weight in conclusions. By omitting elements with marginal influence, the analysis remains focused on those dimensions that demonstrably shape the outcomes, thereby improving the clarity and validity of the study’s findings.

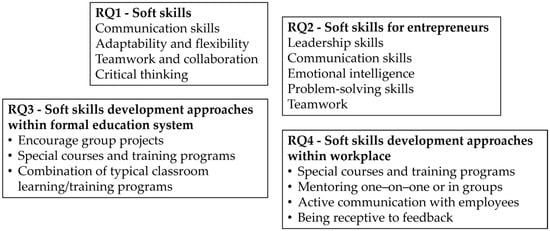

The following figure (Figure 2) presents the final results of the Delphi study conducted in two rounds.

Figure 2.

Delphi study results. Source: Authors.

Figure 2 presents soft skills whose importance has been emphasized for entrepreneurs. Future research should focus on exploring the impact of proposed ways for soft skills development in the formal education system and in the workplace on employees’ soft skills level.

5. Discussion

Soft skills are recognized for their transferability across various occupations, allowing individuals to adapt to changes and engage in lifelong learning, which is increasingly important in a technology-driven environment (Polakova et al., 2023). In the 21st century, labor market requirements are such that graduates as future employees have to acquire skills such as communication and teamwork to boost their employability (Suarta et al., 2017). Accordingly, experts participating in the Delphi study, when answering the first research question about soft skills necessary for the modern business environment, recognized communication skills, adaptability and flexibility, teamwork and collaboration, and critical thinking as being of high importance. Regarding what soft skills experts find to be most crucial not only for contemporary business conditions but also for future entrepreneurs, the common attitude of experts is that those skills are leadership skills, communication skills, emotional intelligence, problem-solving skills, and teamwork.

One of the soft skills highly appreciated by labor market representatives in both cases of regular and entrepreneurial ventures in the Delphi study is communication skills. Similarly, the study of Weber et al. (2011) revealed that HR representatives and educators find communication skills important for first-level managers. It aligns with the growing recognition in the literature that communication skills, both verbal and non-verbal, mainly understood as the effective and assertive exchange of information in team and client interactions, rather than general verbal ability, are essential for success in entrepreneurship, thereby reinforcing the argument for their inclusion in educational programs (Abaci, 2022). Moreover, university accelerator programs can serve as a comprehensive platform for entrepreneurs to develop and enhance their communication skills. Through mentorship, coaching, collaborative learning, self-awareness training, solving real-world situations, and receiving feedback, which is critical for their success in the competitive business landscape, students can enhance different aspects of communication skills (McGloin et al., 2023).

The second skill recognized as a soft skill needed for doing business in modern conditions and entrepreneurship is teamwork. Teamwork and cooperation, together with the entrepreneurial orientation of employees, are essential skills for boosting organizational performance. Teamwork skills are also necessary for achieving common goals when working in situations with an average risk, as in the research of Otache and Mahmood (2015). Educators claim that teamwork is regularly developed during joint tasks given to students. They stress that tasks assigned to students must require know-how from various fields of entrepreneurship or interdisciplinarity and a significant amount of time (Kotey, 2007; Vogler et al., 2018). Teamwork is also mapped as a skill of future entrepreneurs. It is in line with the results of the study of Brinckmann and Hogel (2011), which confirmed that teamwork between the founding team and their external relations is of high importance for business growth. The study of Hebles et al. (2023) emphasizes the importance of integrating cooperative learning methods in entrepreneurship training to foster essential teamwork skills among students. By integrating educational strategies that encourage constructive cognitive conflict while minimizing the risk of interpersonal conflict, entrepreneurship education programs can better prepare students for the challenges of new venture creation and enhance their overall learning experience (Pazos et al., 2022).

Adaptability is identified as the third component of the soft skills cluster and as a skill essential for a person’s performance in business. Individuals and teams can adjust their behaviors, strategies, and approaches in response to changing circumstances, challenges, and environments (Nejad et al., 2021). This includes the capacity to learn new skills, solve problems creatively, and effectively manage unpredictable situations. Adaptability encompasses both individual and team dynamics, emphasizing the importance of flexibility, resilience, and a proactive mindset in navigating complex and dynamic work environments (Pulakos et al., 2006). Dimensions of adaptability, such as handling emergencies, work stress, and uncertain situations, are recognized as important for project managers (Loughlin & Priyadarshini, 2021). In our research, this skill is not mapped as important for future entrepreneurs. This result is not in line with previous studies, since adaptability was identified as a necessary skill of millennial entrepreneurs when dealing with unbalanced business situations (Sirajje et al., 2024).

Emotional intelligence was found to be an essential soft skill in the first round but not as important for modern business conditions in the second round. However, it was identified as a skill needed for starting and running an enterprise in the future. Emotional intelligence refers to the ability to recognize, understand, manage, and influence emotions—both personal and of others. It develops with time, and it can be learned (Serrat, 2017). In line with the results, Dimitrov and Vazova (2020) found that emotional intelligence is one of the important soft skills of employees. On the other hand, Wheeler (2016) stipulated that a person who holds a whole pool of soft skills can be perceived as a person having emotional intelligence. The literature mostly supports the opinion that emotional intelligence is essential for business and management and produces a positive effect on work-related outcomes (Sharma & Tiwari, 2024). In terms of entrepreneurship, emotional intelligence was also found to be beneficial for entrepreneurs because entrepreneurs with high emotional intelligence are more resilient in overcoming obstacles, adept at managing intense emotions in family business dynamics, effective in working with all stakeholders, rated higher on leadership by their teams, and possess a competitive edge in product development, service innovation, and negotiations with key partners (Humphrey, 2013).

In the literature, critical thinking skill is perceived as “purposeful, self-regulatory judgments which result in interpretation, analysis, evaluation, and inference, as well as an explanation of the evidential, conceptual, methodological, criteriological or contextual considerations upon which that judgment is based” (Zabit, 2010, p. 6). According to our research results, critical thinking is identified as a skill necessary for survival in the modern business environment. Avença et al. (2024) did not recognize critical thinking as a soft skills component in employees, such as project managers, but in the case of students’ attitudes, critical thinking is one of five important skills for not only education performance but also for success in a career (Majid et al., 2012). In line with our results, Ayad (2010) highlighted that companies that embrace critical thinking are better positioned to adapt to changes and innovate, thereby achieving significant success in their respective fields. Additionally, for starting/running my own business venture, problem-solving skills were recognized. This skill is closely related to the critical thinking skill, and in the previous studies, problem-solving skill was assessed as a sub-category of critical thinking of both entrepreneurs and aspiring entrepreneurs (Hatthakijphong & Ting, 2019). It can be inferred that critical thinking and problem-solving skills are synonyms. Therefore, there is a growing need to incorporate these skills into educational programs. It is recommended to apply a problem-based learning approach to upskill students in both critical thinking and problem-solving skills (Zabit, 2010).

Leadership skill was one soft skill that was not recognized as important in answers concerning soft skill components for modern conditions. However, it was mentioned by experts as a skill of importance for starting and running one’s own business. The reason why leadership as a skill is not recognized in the previous steps might be because some research studies observe leadership as a multifaceted construct made of soft skills such as communication, initiative, training, and teambuilding skills (Majed, 2019). Moreover, in the case of an entrepreneur, leadership skills are perceived differently. Harrison and Burnard (2023) observe entrepreneurial leadership as a dynamic process that significantly influences the direction and effectiveness of organizations. They emphasize vision, effective communication, creativity, risk-taking, and learning from experience as characteristics of an entrepreneurial leader. Aligned with our Delphi study results, Kadwa and Barnard (2020) stated that entrepreneurship and leadership are mutually interrelated.

According to the Delphi study results, soft skills can be acquired in the education system through group projects, special courses, and training programs, or typical classroom learning/training programs. In the workplace, consensus on the special courses and training programs, mentoring one-on-one or in groups, active communication with employees, and being receptive to feedback was reached. Similarly, Kechagias (2011) identified classroom and workplace learning activities that can enhance students’ learning experience in both contexts. Existing learning models can be upgraded to, for example, experiential learning or project-based learning models. Educational institutions might provide a structured yet flexible framework that allows students to learn by doing, reflect on their experiences, and develop essential skills for their future careers in entrepreneurship (Asbari et al., 2019; Vogler et al., 2018). Moreover, experts participating in the Delphi study highlighted the active part of classroom learning, as in the research of Lavi et al. (2021). Additionally, the study of Widad and Abdellah (2022) showed, in line with our research, that there are different approaches to soft skills development in the workplace. For example, they highlight simulation-based learning strategies, a soft skills educational camp program, an emotional intelligence model, a blended learning pedagogical tool, debating as a learning strategy, action learning, etc. As in the research of Cinque (2016), some of the identified workplace learning activities in our research are guided by special courses and training programs; mentoring one-on-one or in groups can be categorized as expository, and active communication with employees and being receptive to feedback are active soft skills development strategies.

Targeted together by educational programs, both hard and soft skills can increase a person’s productivity and thus their wages (Balcar, 2016). The combination of classroom training with technical assistance was shown to be beneficial for increasing the probability of self-employment and formal employment (Doerr & Novella, 2024). Also, through the development of educational programs for soft skills acquisition, the turnover of workers can be reduced (Weber et al., 2011).

By following these practical recommendations, educators can create a more dynamic and effective learning environment that not only enhances students’ knowledge but also equips them with the necessary soft skills for their future careers, such as entrepreneurial careers. Universities should integrate soft skills development into formal curricula through project-based learning, interdisciplinary teamwork, and stronger partnerships with businesses to better prepare students for entrepreneurial careers. On the other hand, it is a question whether these training programs’ effects will transfer to the business results. Therefore, for successful educational programs, contextual factors should be taken into consideration when making their structure (Wiger et al., 2015). Firms should actively support soft skills development by providing mentoring, training programs, and feedback-oriented work environments that enable young employees and aspiring entrepreneurs to apply these skills in real business contexts. While this study highlights general implications for soft skills development in education and workplace settings, these findings can be more effectively applied when linked to policymakers in the WB countries. Therefore, policymakers need to design coordinated national initiatives that support collaboration between education providers and businesses to strengthen soft skills and entrepreneurial readiness in the WB. Therefore, our study results contribute not only to the literature on soft skills but also fill the gap in the literature on soft skills in the WB context since countries within it have similar labor market characteristics. Specifically, the research addresses a gap in the literature by focusing on the underexplored context of the WB, where systemic educational and labor market challenges shape the development of entrepreneurial soft skills. Moreover, by applying the Delphi method, this study contributes methodologically by capturing expert consensus across multiple WB countries, thus offering region-specific insights and a structured framework for understanding how soft skills can be effectively cultivated through education and workplace practices.

Preconditions of soft skills transfer to learners also depend on work factors, such as job-related factors, autonomy, social support received from peers and supervisors, and organizational facilitation of learning factors (Botke et al., 2018). One more problem that can arise in soft skills training is the teacher’s soft skills development level. Integration of soft skills in educational programs depends on the acquired level of soft skills by the teachers, the perception of the soft skills’ importance by the teachers, and the challenges in effectively integrating soft skills into the curriculum (Ngang et al., 2015; Tang, 2020).

Based on the above, this study has several limitations. The relatively small Delphi panel and the variation in experts’ professional experiences and sector-specific perspectives limit the generalizability of the findings. This study is limited by its reliance on employers’ perspectives without input from educational institutions, which may skew the interpretation of findings toward labor market expectations rather than pedagogical realities, underscoring the need for future research to include education-sector experts for a more balanced understanding of soft skills development. In addition, the results are based on only two Delphi rounds and have not yet been validated on a larger sample. The study also does not assess the long-term effects of soft skills development, nor does it fully account for differences across diverse educational or workplace settings. Future research in this field should address these limitations and thus enable cross-regional replication.

6. Conclusions

In the context of a changing global economy, the focus shifts from hard skills to soft skills when differences emerge between people with the same level of hard skills. This analysis advocates for the application of soft skills in the entrepreneurial endeavors of individuals in the WB. As a result of a Delphi study conducted among twenty experts from Serbia, Albania, North Macedonia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina, a broad agreement was reached on the most critical soft skills relevant and necessary for contemporary business practices and entrepreneurship.

It was found that communication skills, ability to adjust, collaboration, and critical analysis were vital for success in business today and entrepreneurial activities, while leadership and emotional intelligence were considered important, especially for entrepreneurial activities. Moreover, consensus was reached among experts on how to upgrade educational and workplace activities to develop soft skills. The findings emphasize the necessity of aligning educational systems and workplace practices to address identified skill gaps. The experts highlighted effective methods for cultivating these skills, such as integrating group projects, specialized courses, and practical training programs in educational curricula. Workplace-based initiatives, including specialized courses, mentoring, active communication, and feedback mechanisms, were recognized as vital for enhancing soft skills among employees. These strategies collectively contribute to preparing a workforce that is not only technically competent but also resilient and adaptable to entrepreneurial demands.

The application of the Delphi study in the research provides valuable insights with regional relevance for stakeholders. It offers diverse perspectives on shared challenges, facilitates direct consultation with experts actively engaged in the integration of soft skills into daily business practices, and supports ongoing collaboration in identifying opportunities and challenges within the soft skills development process (Hardie et al., 2023). This research contributes to the existing body of knowledge by focusing on the unique context of the WB, a region characterized by significant challenges, including high youth unemployment rates and a pronounced skills mismatch in the labor market. By providing evidence-based insights into the most effective approaches for soft skills development, this study offers valuable guidance for policymakers, educators, and business leaders seeking to foster entrepreneurial capabilities and improve workforce readiness. The study highlights the importance of experiential learning models, such as project-based and hands-on learning, in bridging the gap between theoretical education and practical skill application in the WB context. To develop programs that allow students to gain practical experience in the workplace, develop critical thinking skills through problem structuring and solving, develop communication skills through practical business experience, and learn ethical practices in managing relationships with stakeholders, universities, policymakers, and firms, they should begin working together with the long-term goal of creating such programs (Cacciolatti et al., 2017). The experiential approach of “learning by doing” is widely regarded as one of the most effective methods for fostering soft skills development and practical understanding of a nascent entrepreneur (Cimatti, 2016).

The practical contribution of this study lies in offering actionable recommendations for educators, firms, and policymakers to strengthen soft skills development through experiential learning, mentoring, and coordinated education–business collaboration tailored to the WB context. The theoretical contribution addresses the gap in existing literature by examining how regional socio-economic conditions influence entrepreneurial soft skills and by applying the Delphi method to provide a structured, expert-based framework for understanding their development in transitional economies.

This study is not without limitations. The application of the Delphi study highlights the challenge of generalizing results due to the limited number of participating experts and the varying levels of their expertise. Therefore, future research should validate the obtained results through a broader research focus by using the same questionnaire created at the end of round two of the Delphi study. Future research should also expand on these findings by exploring the longitudinal impacts of soft skills training and identifying educational models that can be replicated across diverse settings. By doing so, stakeholders can build a robust framework for cultivating a workforce that is not only prepared for the labor market challenges assessed through hard skills level but also through the level of development of soft skills.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A. and M.R.; methodology, M.R. and S.M.Z.; software, S.M.Z.; validation, A.A. and M.R.; formal analysis, M.R.; investigation, S.P., S.D. and P.G.; resources, A.A., S.P., S.D. and P.G.; data curation, S.M.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, M.R. and S.M.Z.; writing—review and editing, A.A. and S.M.Z.; visualization, S.M.Z.; supervision, A.A.; project administration, A.A.; funding acquisition, M.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is part of the 101120390-USE IPM-HORIZON-WIDERA-2022-TALENTS-03-01 project, funded by the European Union. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the authors only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Research Executive Agency. Neither the European Union nor the European Research Executive Agency can be held responsible for them.

Institutional Review Board Statement

According to the Law on Science and Research (Official Gazette RS, no. 49/2019) and the Law on Personal Data Protection (Official Gazette RS, no. 87/2018), research of this type (expert consultation without sensitive data) does not require Ethics Committee approval. Nevertheless, the study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki (1975, revised 2013). An informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their involvement. This ensures compliance with international ethical standards as well as institutional requirements.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Abaci, N. I. (2022). Relationship between entrepreneurship perception and communication skill: A structural equation model. International Journal of Management Education, 20(3), 100725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amalu, E. H., Short, M., Chong, P. L., Hughes, D. J., Adebayo, D. S., Tchuenbou-Magaia, F., Lähde, P., Kukka, M., Polyzou, O., Oikonomou, T. I., Karytsas, C., Gebremedhin, A., Ossian, C., & Ekere, N. N. (2023). Critical skills needs and challenges for STEM/STEAM graduates increased employability and entrepreneurship in the solar energy sector. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 187, 113776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asbari, M., Wijayanti, L. M., Hyun, C. C., Purwanto, A., Santoso, B., & Article, H. (2019). Effect of tacit and explicit knowledge sharing on teacher innovation capability. Dinamika Pendidikan, 14(2), 227–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avella, J. R. (2016). Delphi panels: Research design, procedures, advantages, and challenges. International Journal of Doctoral Studies, 11, 305–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avença, I., Domingues, L., & Carvalho, H. (2024). Do the project manager’s soft skills foster knowledge sharing? Project Leadership and Society, 5, 100139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayad, A. (2010). Critical thinking and business process improvement. Journal of Management Development, 29(6), 556–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayre, C., & Scally, A. J. (2014). Critical values for Lawshe’s content validity ratio: Revisiting the original methods of calculation. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 47(1), 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcar, J. (2016). Is it better to invest in hard or soft skills? Economic and Labour Relations Review, 27(4), 453–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, W., & Uvalic, M. (2018). Education system, labor market and economic development—Challenges and prospects (I. Miftari, V. Prenaj, & M. Gjonbalaj, Eds.; pp. 13–30). Kosova Academy of Sciences and Arts. [Google Scholar]

- Botke, J. A., Jansen, P. G. W., Khapova, S. N., & Tims, M. (2018). Work factors influencing the transfer stages of soft skills training: A literature review. Educational Research Review, 24, 130–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, S. R. (2015). Utilizing and adapting the Delphi method for use in qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 14(5), 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinckmann, J., & Hogel, M. (2011). Effects of initial teamwork capability and initial relational capability on the development of new technology-based firms. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 5, 37–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacciolatti, L., Lee, S. H., & Molinero, C. M. (2017). Clashing institutional interests in skills between government and industry: An analysis of demand for technical and soft skills of graduates in the UK. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 119, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimatti, B. (2016). Definition, development, assessment of soft skills and their role for the quality of organizations and enterprises. International Journal for Quality Research, 10(1), 97–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinque, M. (2016). “Lost in translation”. Soft skills development in European countries. Tuning Journal for Higher Education, 3(2), 389–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalkey, N., & Helmer, O. (1963). An experimental application of the Delphi method to the use of experts. Management Science, 9(3), 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dammert, A. C., & Nansamba, A. (2023). Skills training and business outcomes: Experimental evidence from Liberia. World Development, 162, 106120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, J. (2017). A matter of opinion: The Delphi method in the social sciences. SAGE Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Villiers, M. R., de Villiers, P. J. T., & Kent, A. P. (2005). The Delphi technique in health sciences education research. Medical Teacher, 27(7), 639–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrov, Y., & Vazova, T. (2020). Developing capabilities from the scope of emotional intelligence as part of the soft skills needed in the long-term care sector: Presentation of pilot study and training methodology. Journal of Primary Care and Community Health, 11, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doerr, A., & Novella, R. (2024). The long-term effects of job training on labor market and skills outcomes in Chile. Labour Economics, 91, 102619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Training Foundation. (2021). Youth disengagement and skills mismatch in the Western Balkans. Available online: https://www.etf.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2021-11/02_youth_western_balkans_final.pdf#:~:text=Several factors could explain the,during such transition periods such (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- European Training Foundation. (2024). Education, skills and employment-trends and developments 2023: An ETF cross-country monitoring report. Available online: https://www.etf.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2025-01/ETF%20CrossCountry%20Monitoring%20Report%202024_EN%20FINAL.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Fink-Hafner, D., Dagen, T., Dousak, M., Novak, M., & Hafner-Fink, M. (2019). Delphi method: Strengths and weaknesses. Metodoloski Zvezki, 16(2), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebrye, T., Mbada, C., Hakimi, Z., & Fatoye, F. (2024). Development of quality assessment tool for systematic reviews and meta-analyses of real-world studies: A Delphi consensus survey. Rheumatology International, 44(7), 1275–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gribben, A. A. (2018). Tackling policy frustrations to youth entrepreneurship in the Western Balkans. Small Enterprise Research, 25(2), 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardie, B., Lee, K., & Highfield, C. (2023). Utilisation of a Delphi study to understand effective entrepreneurship education in schools. SN Social Sciences, 3(8), 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, C., & Burnard, K. (2023). Entrepreneurial leadership: A systematic literature review. International Review of Entrepreneurship, 14(2), 235–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, N. H. M., Ahmad, K., & Salehuddin, H. (2022). Developing and validating instrument for data integration governance framework. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications, 13(2), 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatthakijphong, P., & Ting, H. I. (2019). Prioritizing successful entrepreneurial skills: An emphasis on the perspectives of entrepreneurs versus aspiring entrepreneurs. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 34, 100603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haven, T. L., Errington, T. M., Gleditsch, K. S., van Grootel, L., Jacobs, A. M., Kern, F. G., Piñeiro, R., Rosenblatt, F., & Mokkink, L. B. (2020). Preregistering qualitative research: A Delphi study. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebles, M., Yaniz-Alvarez-de-Eulate, C., & Jara, M. (2023). Teamwork competence and collaborative learning in entrepreneurship training. European Journal of International Management, 20(2), 238–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendarman, A. F., & Cantner, U. (2018). Soft skills, hard skills, and individual innovativeness. Eurasian Business Review, 8(2), 139–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, R. H. (2013). The benefits of emotional intelligence and empathy to entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Research Journal, 3(3), 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, K. E., Webster, A. C., Clarke, M., Page, M. J., Libesman, S., Godolphin, P. J., Aberoumand, M., Rydzewska, L. H. M., Wang, R., Tan, A. C., Li, W., Mol, B. W., Willson, M., Brown, V., Palacios, T., & Seidler, A. L. (2022). Development of a checklist of standard items for processing individual participant data from randomised trials for meta-analyses: Protocol for a modified e-Delphi study. PLoS ONE, 17(10), e0275893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ILO. (2019). Small matters!—Global evidence on the contribution to employment by the self-employed, micro-enterprises and SMEs. International Labour Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Jandrić, M., & Ranđelović, S. (2018). Adaptability of the workforce in Europe—Changing skills in the digital era. Zbornik Radova Ekonomskog Fakulteta u Rijeci/Proceedings of Rijeka Faculty of Economics, 36(2), 757–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadwa, I., & Barnard, B. (2020). The perceptions of entrepreneurs on the impact of leadership on entrepreneurship and innovation. The IUP Journal of Entrepreneurship Developnet, XVI(4), 7–43. [Google Scholar]

- Kechagias, K. (2011). Teaching and assessing soft skills. In The measuring and assessing soft skills project. 1st Second Chance School of Thessaloniki (Neapolis) Str. Strempenioti, 1st and 3rd Gymnasium 56760 Neapolis (Thessaloniki). [Google Scholar]

- Kotey, B. (2007). Teaching the attributes of venture teamwork in tertiary entrepreneurship programmes. Education and Training, 49(8–9), 634–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavi, R., Tal, M., & Dori, Y. J. (2021). Perceptions of STEM alumni and students on developing 21st century skills through methods of teaching and learning. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 70, 101002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawshe, C. H. (1975). A quantitative approach to content validity. Personnel Psychology, 28, 563–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linstone, H., & Turoff, M. (2002). The Delphi method: Techniques and applications. Addison-Wesley Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Loughlin, E. M., & Priyadarshini, A. (2021). Adaptability in the workplace: Investigating the adaptive performance job requirements for a project manager. Project Leadership and Society, 2, 100012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majed, S. (2019). The role of leadership soft skills in promoting the learning entrepreneurship. Journal of Process Management and New Technologies, 7(1), 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majid, S., Liming, Z., Tong, S., & Raihana, S. (2012). Importance of soft skills for education and career success. International Journal for Cross-Disciplinary Subjects in Education, 2(2), 1036–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchau, V., & van de Linde, E. (2016). The Delphi method. In P. van der Duin (Ed.), Foresight in organisations. Methods and tools (pp. 59–79). Taylor & Francis. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/2066/170791 (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- McGloin, R., Saxton, A., Rao, A., Hintz, E., Coletti, A., Hamlin, E., Turner, M., & Mathieu, J. (2023). Examining the importance of developing entrepreneurial communication skills in accelerator programs: A focus group based approach. Entrepreneurship Education and Pedagogy, 7(4), 468–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muktar, M., & Mohd Matore, M. (2021). Validation of psychological well-being measurement itemsusing content validity ratio technique. Journal of Contemporary Issues in Business and Government, 27(2), 6083–6095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejad, H. G., Nejad, F. G., & Farahani, T. (2021). Adaptability and workplace subjective well-being: The effects of meaning and purpose on young workers in the workplace. Canadian Journal of Career Development, 20(2), 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]