Abstract

This study aimed to examine the effect of public policies on talent retention in the Portuguese Public Administration and whether the participants’ managerial status moderates this relationship. A total of 282 individuals, active workers in public administration, participated in this study, with 11.7% of the total occupying management positions. This is a cross-sectional study with a quantitative approach, using a questionnaire. The results showed that public policies (recruitment, training and performance evaluation) have a positive and significant effect on talent retention. Whether an individual is a manager or not has a significant effect on performance evaluation. No moderating or mediating effect was found. This study aimed to provide data that can inform managers’ decisions and enhance talent management in public administration.

1. Introduction

The public sector in Portugal has been profoundly impacted by recent crises, including forest fires, the COVID-19 pandemic, and other international conflicts, which have necessitated rapid responses and the restructuring of increasingly complex public systems and policies. These crises have had direct impacts on economic stability, the cost of living, and public finances, forcing the state to implement ongoing adjustment measures and reassess the organization and management of its resources (Governo de Portugal, 2024; Banco de Portugal, 2024).

The efficiency of the public sector depends mainly on the strategic valuation and management of its human resources [HR], considered the State’s main asset. Effective retention strategies are essential to ensure the quality of public services, preserve organizational knowledge, and promote operational stability, thereby contributing to the country’s development. However, budgetary restraint policies have hampered external recruitment, leading to a shortage of HR and an aging workforce, which limits the strategic response capacity of the Public Administration [PA] and constrains the implementation of innovative people management practices (INA, 2018).

Opportunities for professional development, continuous learning, work–life balance, and dynamic career paths are essential to motivate and retain skilled workers in the PA. High turnover entails increased costs and loss of human capital, negatively affecting the quality of services and the responsiveness of the State (OECD, 2021; Moreira & Coutinho, 2022).

In this context, talent management and leadership development play a crucial role in addressing the current challenges of the PA, promoting motivated and innovative teams that are aligned with the public sector’s mission. However, studies on talent retention and the role of management in the Portuguese PA are still scarce, with most research focusing on the private sector or general approaches. This gap hinders understanding of the specificities of the public sector and the dynamics of leadership and motivation (Delisle & Rinfret, 2006).

Several studies on public policy exist, including the study conducted by Fialho et al. (2023), which examines the relationship between leadership and public policy. However, we did not find any studies that related public policy to retention intentions in Portugal. It was this gap that led us to conduct this research.

In view of these challenges, this research seeks to answer the following question: how do public policies on recruitment, training, and performance evaluation influence talent retention in the Portuguese PA, and what is the role of management in this process?

To answer this question, we employed document analysis and questionnaires to propose recommendations that enhance the attractiveness, motivation, and retention of public sector professionals, thereby contributing to the sustainability and quality of services provided to citizens.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Public Administration

The PA is responsible for meeting the collective needs of society through services organized and maintained by the community, covering areas such as security, culture, and well-being (DGAEP, 2018a). According to Amaral (2014), public services can have different origins and natures: some are administered by local communities, others are offered in competition by public and private entities, and there are also services performed exclusively by specially qualified companies. Despite these differences, they all aim to satisfy collective needs on a regular and continuous basis.

PA is not limited to the central Government but includes a wide range of entities and bodies with their own legal personality, such as municipalities, parishes, autonomous regions, universities, public institutes, public companies, public associations, and other legal entities of public utility (DGAEP, 2018a; Amaral, 2014).

According to the DGAEP (2018a), PA can be understood in two ways:

- (1)

- Organic sense: PA is the system of bodies, services, and agents of the State and other public entities that aim to regularly and continuously meet collective needs.

- (2)

- Material sense: the PA is the activity itself carried out by these bodies, services, and agents to meet these needs (DGAEP, 2018a).

The structure of the Portuguese PA can be divided into three main groups of entities:

- (1)

- Direct State Administration: this comprises all bodies, services, and agents integrated into the legal entity known as the State, under the hierarchical authority of the Government, with competences exercised at the central (central services) or territorial (peripheral services) level.

- (2)

- Indirect State Administration: includes public entities with legal personality and administrative and financial autonomy, such as public institutes, personalized funds, and public business entities. These entities carry out administrative activities on behalf of the State’s own purposes and are subject to the supervision and oversight of the Government, but with greater autonomy.

- (3)

- Autonomous Administration: this includes entities that pursue the interests of the populations or members that constitute them, with independence and autonomy in their orientation and activity. This group includes Regional Administration (autonomous), Local Administration (autonomous), and public associations, which are only subject to the supervision of the Government (DGAEP, 2018a).

Each group has a different level of relationship with the Government, ranging from hierarchical subordination (Direct Administration) through supervision and oversight (Indirect Administration) to almost total autonomy (Autonomous Administration). This complex structure allows the PA to respond in a diversified and decentralized manner to collective needs, promoting efficiency, transparency, and proximity to citizens (DGAEP, 2018a).

2.2. Evolution of Public Policies in Portugal

Over the last three decades, Portugal has undergone successive reforms aimed at modernizing, reducing bureaucracy, and improving the performance of public institutions, influenced by the principles of New Public Management (NPM). These reforms promoted the restructuring of organizations, the introduction of business management practices, and, in some cases, the privatization of services, with a significant impact on the PA. The Troika period (2011–2014) was particularly notable, marked by the implementation of austerity measures and administrative rationalization to reduce public spending (Madureira, 2015; Bilhim, 2021).

These changes led to greater convergence between the public and private sectors, but also presented challenges, including a decline in the number of workers, an aging workforce, and difficulties in motivating and retaining public administration professionals (OECD, 2017; DGAEP, 2018b). The use of outsourcing and public–private partnerships has been limited, keeping Portugal below the OECD average in these practices. The aging of the workforce has worsened, with more than 60% of employees over the age of 45 in 2017 (DGAEP, 2018b).

Among the most significant reforms are the establishment of the Integrated Performance Evaluation System in Public Administration (IPESPA), the revision of the Statute of Senior Staff, the introduction of mobility schemes and career merging, as well as the alignment of civil service contracts with the private sector regime. Despite progress, cultural and legal resistance persists, as do negative impacts on worker motivation, often associated with instability and a perception of insecurity resulting from organizational changes (Bustos, 2023).

2.3. Training

In the context of PA, Lei No. 86/2016 (2016), of 29 December, of the Ministry of Finance, defines professional training as “the comprehensive and ongoing process of acquiring and developing the competence required to perform a professional activity or to improve performance, promoting the personal and professional development and advancement of public administration employees and managers, which does not confer an academic degree.” This decree aims to ensure that PA HR is prepared to perform its duties effectively, efficiently, and innovatively, recognizing training in the workplace as a strategic tool for modernizing the public sector. Training may be initial, continuous, or professional development, and is promoted by the INA, sectoral training entities, the PA’s own bodies and services, as well as certified public or private training entities (INA, 2024). The decree also provides that training activities shall be subject to continuous evaluation, and the preparation of training management reports is mandatory.

At the same time, Lei No. 35/2014 (2014) of 20 June, of the Assembly of the Republic, establishes the training of public service workers as a right, with public employers responsible for promoting certified and recognized actions aimed at updating and improving workers’ competences, ensuring professional development opportunities for all.

2.4. Recruitment and Selection

In the context of PA, recruitment is a structured process that aims to attract and select suitable candidates for public office. The promoting bodies and services manage it and is generally carried out through a competitive selection process (Order No. 6061/2020, of 4 June, by the Recruitment and Selection Committee for Public Administration; Lei No. 2, of 15 January 2004, by the Assembly of the Republic).

Recruitment in the PA is usually carried out through the so-called common competitive procedure or through internal mobility, exclusively for workers with permanent public employment contracts. The recruitment of candidates without a permanent link to the PA is only possible with justified authorization, and only when it is demonstrated that it is impossible to fill the position with a worker holding a permanent contract. In addition, the existence of the job in the staffing plan, the absolute need for the position to be filled, the availability of budgetary resources, and the absence of a recruitment reserve are mandatory conditions for the opening of the procedure (Ordinance No. 233/2022, of 9 September, of the Presidency of the Council of Ministers; DGAEP, 2025).

To meet future needs, a centralized competitive procedure, coordinated by the DGAEP, is also in place. This procedure aims to establish recruitment reserves for later use by public employers, in accordance with periodic surveys of needs. Job offers must be advertised on dedicated electronic platforms, on the service’s website and, in many cases, in the Diário da República (Official Gazette), ensuring transparency and equal access (DGAEP, 2025).

The selection process comprises both mandatory and optional methods, as outlined in the notice of opening the competitive selection procedure. It is conducted by a previously constituted jury, ensuring objectivity and impartiality (Ordinance No. 233/2022, of 9 September, by the Presidency of the Council of Ministers; DGAEP, 2025). There are also specific competitive procedures for special projects under the Recovery and Resilience Plan [PRR], always in coordination with the DGAEP. The recruitment and selection of senior managers is ensured by the Recruitment and Selection Committee for Public Administration [CReSAP], in accordance with criteria of merit and transparency, under the terms of Lei No. 2/2004 (2004), of 15 January, of the Assembly of the Republic, amended by Lei No. 128/2015 (2015), of 3 September, of the Assembly of the Republic.

2.5. Performance Evaluation

Performance evaluation, as defined by Fahim (2018), consists of the process of evaluating how well workers perform their tasks in comparison with previously established standards. In the PA, employee performance assessment is regulated by Article 90 of the General Lei on Public Service [LTFP], which has a direct impact on salary progression, the awarding of performance bonuses, and any disciplinary measures. The primary objective of this process is to promote continuous service improvement, identify training and development needs, and recognize and reward employee merit. This system applies to all public employees, except for members of the government, local elected officials, and individuals in other political positions, with a few exceptions. It is based on the achievement of objectives. Responsibility for evaluation lies with the heads and managers of public entities, who must ensure the proper implementation of the system (Lei No. 35 of 20 June 2014, of the Assembly of the Republic).

2.6. Talent Retention

Talent retention has several definitions in the scientific literature. According to L. Silva and Dinis (2021), it is a set of actions aimed at retaining talented employees in organizations, having a positive impact on the generation of value, productivity, and employee motivation. Cunha and Martins (2015) describe talent retention as the creation of strategies to attract, identify, develop, and retain employees with strong potential, capabilities, and skills, aiming to retain qualified professionals within the organization. Faced with challenging scenarios that require practical HR adaptations, Nunes et al. (2021) state that talent retention should also involve diagnosing and implementing processes that ensure the retention of valuable professionals in organizations. Talent retention involves strategies for attracting, identifying, developing, and retaining employees with strong potential, capabilities, and skills. Strategic talent retention management encompasses employee loyalty through attractive benefits, as well as opportunities for personal and professional development. Specific policies and practices within each organization offer employees attractive means of growth, incentives, and opportunities for professional and personal development (Cunha & Martins, 2015).

Personal growth in the organizational context is a dynamic process that involves both advances and setbacks in individual performance, encompassing actions such as self-awareness, strengthening of worker identity, and competence development and potential (Chiavenato, 2014; Schein, 2010). The HR sector plays a central role in this process, acting not only as a process manager but also as a strategic partner that promotes quality of life, the fulfillment of aspirations, and the continuous development of employees. When HR and leadership recognize workers as whole human beings, they create conditions to bring out the best in each employee, identify areas for improvement, and foster a healthy and motivating work environment (Goleman, 2000). Participatory leadership is fundamental in this context: leaders who practice active listening, transparency, and collaboration can anticipate signs of demotivation and take preventive action to avoid losing talent, promoting team involvement and commitment. For this to happen, it is essential to have a participatory leader who is focused on the organizational objectives behind the planning (E. Silva et al., 2023). Leaders must be attentive and act before employees lose motivation or decide to leave due to a lack of incentive.

Recognizing the value of employees is essential for them to feel appreciated. This appreciation can bring several benefits to the organization, such as reduced turnover, increased commitment, and the creation of a positive work environment that encourages the continuous development of everyone. Among the practices that promote employee appreciation are public recognition of efforts, effective communication between teams, initiatives to promote employee development, demonstrating trust, and social gatherings and events (E. Silva et al., 2023).

2.7. Public Policies and Retention Intentions

Scientific literature has shown that training policies have a positive impact on retention intentions in primary care, since professional development contributes to the perception of value and the creation of opportunities for advancement, factors that reduce turnover intentions and increase organizational commitment (Benson, 2006; Cho & Lewis, 2012; Meyer et al., 2002; Cunha & Martins, 2015). Benson (2006) demonstrates that the impact of training on retention can be either positive or negative, depending on how it is organized and perceived by workers.

This relationship can be understood through various theories. Among these, the theories of social exchange and the norm of reciprocity stand out. According to the theory of social exchange, developed by Blau (1964), employees establish mutual and contingent exchanges with the organization, which will determine the beginning, maintenance and end of a relationship. On the other hand, the norm of reciprocity, previously developed by Gouldner (1960), suggests that employees respond to positive actions by the organization with other positive actions, thus creating a dynamic of mutual benefits for both parties. Another theory that justifies this relationship is the theory of planned behavior, developed by Ajzen (2012). According to this theory, behavioral intentions are causal antecedents of behavior; that is, when employees have a strong intention to remain in their public organization, the chances of them staying are higher.

Therefore, based on the reasons outlined above, Hypothesis 1a is formulated:

Hypothesis 1a.

Training policies are positively and significantly related to retention intentions in the PA.

The literature indicates that effective recruitment, based on merit and suitability for the position, contributes to the selection of professionals who align with the organizational culture, thereby promoting their retention within the organization (Kellough & Osuna, 1995; Perry & Wise, 1990; Cunha & Martins, 2015). Recruitment procedures governed by transparency and methodological rigor not only increase the likelihood of identifying candidates with the required competences but also reinforce the perception of organizational justice, an essential element for strengthening long-term employee commitment (Kellough & Osuna, 1995).

Thus, Hypothesis 1b is formulated:

Hypothesis 1b.

Effective recruitment and selection processes are positively and significantly related to retention intention in the PA.

The literature indicates that fair and transparent performance assessments are crucial in preventing frustration and demotivation in the public sector, as they have a direct impact on employee motivation and commitment (Cho & Lewis, 2012; Moitinho, 2011). Fair evaluation systems promote engagement and reduce turnover intentions by ensuring that performance is rewarded fairly (Cho & Lewis, 2012). However, Reis (2015) indicates that, although performance assessment is recognized as a relevant tool for managing and motivating workers, many employees perceive the system as unfair and unmotivating, especially when they do not feel that recognition and progression are effectively linked to merit. This negative perception can compromise the expected impact of performance assessment on employee retention and motivation in the civil service.

Thus, based on the literature and legal frameworks, Hypothesis 1c is formulated:

Hypothesis 1c.

Performance evaluation system is positively and significantly related to retention intentions.

2.8. Management, Retention Intentions and Public Policies

With the evolution of management theories, particularly the emergence of transformational leadership, more flexible, motivating, and development- and talent-retention-oriented leadership styles have come to be valued.

Carroll (2016) suggests that well-intentioned leaders may encounter administrative obstacles that hinder their ability to implement retention strategies in the manner they consider adequate. Tupari et al. (2024) affirm that leaders have a prominent place in PA, given their motivating and inspiring role for employees within the organization, arguing that they should be flexible and communicative with workers.

Leaders also tend to show less turnover intention because they value the organization’s reputation and develop greater normative and affective commitment, making them more likely to stay because they identify with its mission (Cho & Lewis, 2012; Meyer et al., 2002; Bustos, 2021).

This leads to Hypothesis 2:

Hypothesis 2.

Whether someone holds a management position or not has a significant impact on their retention intentions.

Perry and Wise (1990), Cunha and Martins (2015), and Pinheiro (2025) argue that the hierarchical level of workers impacts how public policies are implemented and prioritized within the PA. Management directly influences the implementation of recruitment, training, and performance assessment policies, as they have greater decision-making power and are responsible for ensuring efficient selection processes, continuous training, and fair assessments, shaping policies according to their experience and leadership vision.

This leads to Hypothesis 3:

Hypothesis 3.

Whether an employee holds a position of management or not has a significant effect on public policies (recruitment, training, and performance assessment).

Some studies also indicate that leaders play a moderating role, as they moderate the relationship between organizational policies and retention. This is because leaders are responsible for applying and interpreting these policies, and their perceptions of them can directly influence the level of engagement of subordinate workers. Additionally, management that promotes work–life balance tends to increase team retention (Cho & Lewis, 2012; Bustos, 2021).

Based on this analysis, Hypothesis 4 was developed:

Hypothesis 4.

Whether one’s management plays a moderating role in the relationship between public policies and intentions to stay.

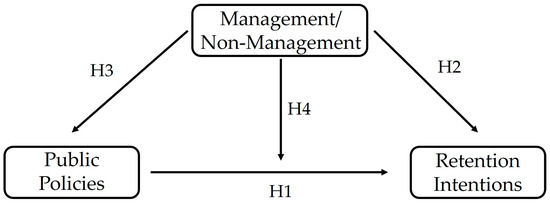

After reviewing the literature, the research model is presented (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Research Model.

3. Methods

3.1. Data Collection Procedure

In this study, 282 individuals working in primary care in Portugal participated voluntarily. The sampling process was non-probabilistic, convenience-based, and intentional (Trochim, 2000). This is a mixed-method (quantitative and qualitative), exploratory, cross-sectional study, as the data will be collected at a single point in time.

The questionnaire was posted online on the Google Forms platform, and the link was shared via email, Facebook, and WhatsApp. Participants were able to view the informed consent form before completing the questionnaire, which allowed them to decide whether they wished to participate in the survey. The document guaranteed the confidentiality of the responses provided.

The questionnaire included sociodemographic information to characterize the sample and two different scales: one on public policies and the other on retention intentions. In addition to closed-ended questions, the public policy questionnaire included three open-ended questions.

3.2. Participants

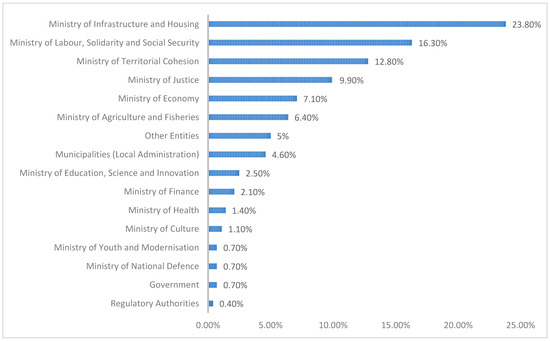

The sample for this study consists of 282 participants, who collaborated voluntarily and are aged between 18 and 66 years old. Of these, 88.3% are not management and 11.7% are management. In terms of gender, 32.3% of participants are male and 67.7% are female. Of these, 16% have a level of education equal to or lower than the 12th grade, 61% have a bachelor’s degree, and 23% have a master’s degree or higher. In terms of the type of contractual relationship, 85.5% have a permanent public service employment contract (CTFP), 1.8% have a fixed-term CTFP, 5.3% have an indefinite CTFP, 6% are appointed, and 1.4% are on secondment.

In terms of seniority in the civil service, 5.3% have less than one year, 15.6% between 1 and 3 years, 6.4% between 4 and 6 years, 6.7% between 7 and 10 years, 8.2% between 11 and 15 years, and 57.8% have more than 15 years. Regarding seniority in the organization, 14.2% have less than 1 year, 31.2% between 1 and 3 years, 15.2% between 4 and 6 years, 10.6% between 7 and 10 years, 6% between 11 and 15 years, and 22.7% have been with the organization for more than 15 years.

Figure 2 shows the distribution of participants by the organization where they work.

Figure 2.

Distribution of participants according to the organization where they work.

3.3. Data Analysis Procedure

After collecting, the information was entered into the SPSS Statistics 29 program to perform the relevant statistical analyses. The first step was to evaluate the metric properties of the instruments used in this study. To verify the instruments’ validity, confirmatory factor analyses were conducted using AMOS Graphics 29. The procedure was based on a ‘model generation’ logic (Jöreskog & Sörbom, 1993), considering the results obtained interactively in the analysis of its fit: for the chi-square ratio (X2) < 5; for the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) > 0.90; for the goodness-of-fit index (GFI) > 0.90; for the comparative fit index (CFI) > 0.90; for the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) < 0.08 (McCallum et al., 1996); and the root mean square residual (RMSR), the lower the value, the better the fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). After performing the CFA, the construct reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity were calculated for each instrument. The reliability of the construct should be greater than 0.70. Convergent validity was tested by calculating the average extracted variance (AVE), which should be greater than 0.50 (Fornell & Larcker, 1981).

As the questionnaire consisted of closed questions, to reduce the impact of the common method variance, the recommendations proposed by Podsakoff et al. (2003) were followed. Two confirmatory factor analyses were performed, one with a single factor and the other with four factors.

To study the descriptive statistics of the variables under study, the student’s t-test for a single sample was used. The association between the variables under study was assessed using Pearson correlations. Hypotheses 1 and 5 were tested using simple and multiple linear regressions. Hypotheses 2 and 3 were tested using Student’s t-tests for independent samples after verifying the respective assumptions. Hypothesis 4, which assumes a moderating effect, was tested using the Macro Process 4.2, Model 1, developed by Hayes (2022), with Bootstrap 10,000. A value of 0.50 was considered the level of significance.

3.4. Instruments

To measure public policies, the questionnaire developed by Fialho et al. (2025) was used (Table A1, Appendix A). This questionnaire consists of nine items distributed across three dimensions: Recruitment, Training, and Performance Evaluation. The nine items are anchored on a five-point Likert scale, from 1 ‘Strongly disagree’ to 5 ‘Strongly agree.’ A three-factor confirmatory factor analysis was carried out to test the validity of this instrument. The fit indices obtained are adequate (χ2/gl = 2.25; GFI = 0.96; CFI = 0.93; TLI = 0.90; RMSEA = 0.067; SRMR = 0.075). All items have factor weights greater than 0.50, which is considered acceptable (Hair et al., 2017). The construct reliability was 0.76 for recruitment, 0.76 for training, and 0.74 for evaluation. Convergent validity has an AVE value of 0.52 for recruitment, 0.51 for training, and 0.54 for evaluation, above the reference value for good convergent validity, according to Fornell and Larcker (1981).

Retention intentions were measured using the instrument developed by Bozeman and Perrewé (2002), adapted to the Portuguese population by Bártolo-Ribeiro (2018), consisting of 6 items (Table A2, Appendix A), classified on a 5-point scale (from 1 ‘Does not apply at all’ to 5 ‘Applies completely’). A one-factor confirmatory factor analysis was carried out to test the validity of this instrument. The fit indices obtained are adequate (χ2/gl = 3.67; GFI = 0.97; CFI = 0.98; TLI = 0.97; RMSEA = 0.078; SRMR = 0.033). All items have factor weights greater than 0.60, which is considered good (Hair et al., 2017). The construct reliability was 0.90. Convergent validity has an AVE value of 0.61, above the reference value for good convergent validity, according to Fornell and Larcker (1981).

4. Results

Two models were tested: one with a single factor and one with four factors. The fit indices obtained in the one-factor model were not adequate (χ2/gl = 6.72; GFI = 0.75; CFI = 0.69; TLI = 0.64; RMSEA = 0.143; SMRM = 0.139). The fit indices for the four-factor model proved adequate (χ2/gl = 1.89; GFI = 0.993; CFI = 0.96; TLI = 0.94; RMSEA = 0.056; SMRM = 0.073). These results conclude that the theoretical conceptualization, which identified four variables, adequately represents the observed data. The correlations are consistent with the theorized pattern of relationships.

4.1. Descriptive Statistics of the Variables Under Study

Next, a descriptive analysis of the variables investigated was conducted to understand how participants’ responses in this study were distributed.

When analyzing the data presented in Table 1, the means of the variables Recruitment, Training, and Evaluation are close to or below the midpoint of the scale (3). Recruitment has a mean of 2.61 (SD = 0.75), significantly lower than the reference value, suggesting that participants tend to attribute less relevance to this dimension (Table 1). Training, with an average of 3.10 (SD = 0.86), shows a statistically significant difference. However, the effect is small, indicating that, although slightly above the midpoint, it does not represent a marked trend (Table 1). In the case of Evaluation, the average obtained of 3.01 (SD = 0.80) practically coincides with the midpoint, with no statistically relevant difference (Table 1).

On the other hand, the Retention Intentions variable stands out from the rest. With an average of 3.56 (SD = 1.06), significantly above the midpoint of the scale, participants tend to want to remain in the organization (Table 1). While the other dimensions reveal more neutral or even slightly negative positions, the intention to remain emerges as a clearly positive aspect among the participants in this study (Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the variables under study.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the variables under study.

| Variable | t | df | p | d | Mean | SD | 95% IC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recruitment | −8.66 *** | 281 | <0.001 | 0.52 | 2.61 | 0.75 | [−0.44; −0.30] |

| Training | 1.89 * | 281 | 0.030 | 0.12 | 3.10 | 0.86 | [0.04; 0.20] |

| Evaluation | 0.30 | 281 | 0.382 | 0.02 | 3.01 | 0.80 | [−0.08; 0.11] |

| Retention Intentions | 8.80 *** | 281 | <0.001 | 0.52 | 3.56 | 1.06 | [0.43; 0.68] |

Note. * p < 0.05; *** p < 0.001.

4.2. Association Between the Variables Under Study

The association between the variables in the group was tested using Pearson correlations.

Recruitment, training and performance evaluation are positively and significantly correlated with retention intentions (Table 2). The higher the perception of fair recruitment, adequate training and fair performance evaluation, the higher the retention intentions (Table 2).

Table 2.

Association between the variables under study.

4.3. Hypotheses

The results indicate that perceptions of fair recruitment are positively and significantly associated with retention intentions (β = 0.34; p < 0.001). The higher the perception of fair recruitment, the higher the retention intentions. The model explains 12% of the variability in retention intentions. The model is statistically significant (F (1, 280) = 37.44; p < 0.001) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Effect of public policies on retention intentions.

Perceived fair training is positively and significantly associated with retention intentions (β = 0.27; p < 0.001). The higher the perception of fair training, the higher the retention intentions. The model explains 8% of the variability in retention intentions. The model is statistically significant (F (1, 280) = 22.71; p < 0.001) (Table 3).

In the case of performance evaluation, the results indicate that the perception of fair evaluation has a positive and significant association with retention intentions but is weaker than for recruitment and training (β = 0.20; p < 0.001) (Table 3). The higher the perception of fair evaluation, the higher the retention intentions. The model explains 4% of the variability in retention intentions. The model is statistically significant (F (1, 280) = 11.53; p < 0.001) (Table 3).

The results obtained support Hypothesis 1.

The results indicate that whether the participant holds a managerial position has no significant effect on retention intentions (t (280) = 0.12; d = 0.02; p = 0.900) (Table 4), with a CI of 95% [−0.36; 0.41].

Table 4.

Effect of leadership/non-leadership on retention intentions.

The results obtained do not support Hypothesis 2.

The results indicate that there are no statistically significant differences between managers and non-managers in their perception of recruitment fairness (t (280) = 1.63, p = 0.104, d = 0.30) (Table 5), with a CI of 95% [−0.05; 0.50].

Table 5.

Effect of Management/Non-Management on Public Policies.

Regarding the training variable, there are no significant differences between managers and non-managers in their perception of training fairness (t (280) = −0.17, p = 0.864, d = 0.03) (Table 5).

Regarding the last variable, managers have a significantly more positive perception of performance evaluation compared to non-managers (t (280) = −2.56, p = 0.011, d = 0.47). The mean for managers (M = 3.34, SD = 0.74) is higher than that for non-managers (M = 2.97, SD = 0.79), with a moderate effect size (Table 5), with a CI of 95% [−0.34; 0.29].

The results show that statistically significant differences exist only in performance evaluation between managers and non-managers, with managers evaluating this process more positively (Table 5). In the areas of recruitment and training, there are no significant differences between the groups (Table 5) with a CI of 95% [−0.66; −0.09].

The results obtained partially support the hypothesis.

As Hypothesis 4 assumes a moderating effect, it was tested using the Macro Process (Model 1) developed by Hayes (2022), with Bootstrap 10,000.

Regarding the moderating effect of leadership/non-leadership on the relationship between public policies (recruitment, training, and evaluation) and retention intentions, this effect was not verified, as the confidence interval in all analyses contains zero (Table 6).

Table 6.

Moderated effect.

The results obtained do not confirm the hypothesis.

5. Discussion

This study aimed to examine the association between public policies and retention intentions, and whether this relationship is moderated by whether the participant holds a management position.

Firstly, the results confirm that recruitment, training and performance evaluation policies are positively associated with retention intentions in the civil service, albeit with varying degrees of intensity.

Hypothesis 1a, which states that training policies are positively and significantly related to retention intentions, was confirmed, as training showed a positive association with retention. This situation is corroborated by the studies of Benson (2006) and Cunha and Martins (2015), which highlight the role of training in organizational commitment, and Meyer et al. (2002), which indicates that the development of workers’ skills promotes affective and normative commitment. The results also partially confirm the theory of Cho and Lewis (2012), which posits that training and professional growth are key determinants of worker retention in the public sector, particularly among the most experienced workers. However, the low R2 (8%) suggests that training alone is not sufficient, requiring integration with other policies to maximize its effect.

Hypothesis 1b, which indicates that recruitment policies are positively and significantly related to intentions to remain, was confirmed, with recruitment being the strongest predictor in its relationship with intentions to remain. These results are in line with the studies by Perry and Wise (1990) and Kellough and Osuna (1995), who advocate meritocratic and transparent processes to strengthen long-term employee commitment, as well as the study by Cunha and Martins (2015), who argue that recruitment practices that are in line with the organization’s values and goals strengthen the creation of lasting bonds with the institution.

Hypothesis 1c, which states that performance evaluation policies are positively and significantly related to intentions to remain, was also confirmed, showing a relationship with intentions to remain, but at a lower level than the other variables, reflecting the perception of injustice observed by employees and reported by Reis (2015) and Madureira (2020). Managers tend to evaluate the system more positively than non-managers, demonstrating their greater involvement and identification with hierarchical objectives (Bustos, 2021; Meyer et al., 2002).

The results of Hypotheses 1a, 1b, and 1c can also be interpreted in light of social exchange theory (Blau, 1964), the norm of reciprocity (Gouldner, 1960), and planned behaviors theory (Ajzen, 2012). Social exchange theory (Blau, 1964), as well as the norm of reciprocity (Gouldner, 1960), proposes that reciprocity exists between the employee and the organization, and how this reciprocity is related to the perception and importance that employees attribute to fair public policies. A high perception of public policies, such as recruitment, training, and performance evaluation, enhances retention intentions. According to the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, 2012), behavioral intentions are causal antecedents of behavior. When an employee has high levels of retention intentions, they are more likely to remain active in the organization where they work.

Secondly, Hypothesis 2, which states that whether or not one holds a managerial position has a significant effect on intentions to remain, was not confirmed, contradicting the studies by Cho and Lewis (2012), Meyer et al. (2002) and Bustos (2021), which indicate that managers tend to have fewer intentions to leave due to their greater affective and normative commitment to the organization. The hierarchical culture of the PA can explain the non-confirmation of the hypothesis indicated by Bilhim (2021), which may have neutralized the effect, as managers face additional pressures, such as the implementation of unpopular policies. Thus, whether one is a manager or not does not significantly impact the decision to remain in the PA.

Thirdly, Hypothesis 3, which indicates that whether or not one holds a managerial position has a significant effect on public policies (recruitment, training and performance evaluation), was only partially confirmed. Managers have a significant impact on public policies related to performance evaluation, but do not significantly influence other policies. This conclusion contradicts the argument presented by some studies (Perry & Wise, 1990; Cunha & Martins, 2015; Pinheiro, 2025), which suggest that the deliberative power of managers enables them to shape public policies based on their experiences and vision. However, Madureira (2020) explains that managers in the PA often must reproduce authoritarian models, limiting their ability to innovate.

Fourthly, Hypothesis 4 suggests that whether one is a manager plays a moderating role in the relationship between public policies and intentions to remain. This hypothesis was not confirmed, as the moderating effect was not statistically significant, which contrasts with the argument put forward by Bustos (2021), who suggests that managers’ perceptions of public policies can influence the level of retention among subordinate workers. This may suggest that the cultural rigidity of the PA and the lack of autonomy of leaders (Bilhim, 2021) may consequently limit the role of managers. These results may also have been influenced by the fact that this study was conducted in Portugal, a country with a culture characterized by high hierarchical distance, as noted in Hofstede’s (1991) study. Furthermore, in Portuguese public administration, the predominant leadership style is still more transactional than transformational (Fialho et al., 2023).

Regarding the descriptive statistics of the variables under study, while the other dimensions of the public policy instrument (recruitment, training, and evaluation) reveal more neutral or even slightly negative positions, the intention to remain emerges as a clearly positive aspect among the participants in this study.

5.1. Limitations and Future Research

The context of the PA presents specific challenges that constitute limitations in interpreting the results, which must be considered. Despite efforts to include participants from different PA bodies, it is essential to note that the sample was obtained through convenience sampling rather than probabilistic sampling. This method may introduce selection biases, limiting the representativeness of the results for the Portuguese PA universe. Of note is the overrepresentation of employees with more than 15 years of service (57.8%), a factor that may skew the perceptions collected, as older employees may have different experiences and expectations regarding public policies and their intention to remain in the service compared to more recent employees. In addition, voluntary participation may favor the inclusion of more motivated or more available individuals, potentially increasing voluntary bias.

The sample also has a predominance of participants with stable employment (permanent contracts), which may skew perceptions of retention policies, underestimating the challenges faced by precarious workers. Similarly, the cross-sectional nature of the study prevents a causal analysis or an assessment of the impact of public policy reforms over time. Finally, this study focused on traditional recruitment, training, and performance evaluation policies, and critical variables for retention, such as salary, work–life balance, organizational culture, or the impact of teleworking, were not included in the study. This omission may limit the holistic understanding of the factors that influence employee retention, especially in contexts of digital transformation and generational demands. To overcome these limitations, it is recommended that future studies consider probabilistic sampling methodologies or, where possible, diversify data collection channels to mitigate these biases and increase the robustness of the results.

Longitudinal studies should be adopted to analyze the temporal impact of public policies, such as the revision of IPESPA, on talent motivation and retention. In addition, the inclusion of omitted variables, such as remuneration, flexible working hours, non-monetary recognition, and the perception of distributive justice, is suggested to enrich the multivariate analysis. The integration of big data and predictive analysis tools could also offer insights into emerging trends, such as the impact of artificial intelligence on people management in the public sector.

Another proposal would be to conduct a study using stratified probability sampling across different government entities and multiple data sources (administrative records/supervisor-subordinate). Additional mediating/controlling variables could also be included, such as satisfaction, affective organizational commitment, perception of organizational justice, and perceived organizational support.

5.2. Theoretical Implications

The results confirm that classical principles such as merit, training, and performance evaluation remain relevant to understanding retention in the civil service, in line with the arguments of Chiavenato (2014) and Cunha and Martins (2015). These results are based on social exchange theory (Blau, 1964) and the norm of reciprocity (Gouldner, 1960). When an employee perceives that the organization where they work has good public policies, such as fair recruitment, adequate training and fair performance evaluation, their intention to remain with the organization increases. However, their effectiveness depends on adaptation to the current context, marked by bureaucratic challenges, an aging workforce and demands for modernization (Bilhim, 2021; Madureira, 2020). Although managers did not emerge as significant moderators, their role in the perception and implementation of HR policies is highlighted by Bustos (2021) and Meyer et al. (2002), suggesting that future theoretical models should consider leadership as a critical contextual variable. The literature indicates that retention is not dependent on a single variable, but rather on a combination of policies and organizational factors (Cunha & Martins, 2015; Cho & Lewis, 2012). Thus, there is a need for theoretical models that consider multiple dimensions, such as recognition, development, and the organizational culture of employees.

5.3. Practical Implications

The perception of fairness and transparency in recruitment, highlighted as a critical factor by Cunha and Martins (2015) and supported by the results of this study, underscores the need to reinforce meritocratic practices, provide timely feedback to candidates, and maintain clear communication during public competition procedures. The slowness of recruitment processes was one of the most frequently identified criticisms in the open responses to the questionnaire. This limitation hinders the AP’s ability to attract new talent, particularly in a competitive environment with the private sector. To address this challenge, it is recommended that recruitment procedures be simplified and digitized, utilizing online platforms for submitting applications and communicating with candidates. This measure can increase transparency, reduce response time and make the AP more agile and competitive.

Continuous training should be aligned with the real needs of employees and services, as advocated by Benson (2006) and Chiavenato (2014), and valued in career progression to enhance its impact on motivation and retention. Although the results demonstrate its positive impact on the intention to remain, participants mention the need to diversify and strengthen the training offer. Managers should therefore invest in continuous training plans, adapted to the specific needs of each service and employee, and promote mentoring and peer learning programs. Investing in modular training and cross-cutting skills can increase employee engagement and contribute to their professional development.

The results and the literature (Reis, 2015; Madureira, 2020) suggest that performance appraisal systems should be fairer, more participatory and development-oriented, incorporating regular feedback and effective recognition of merit. IPESPA has been identified as a central instrument, but it has been criticized for its fairness and transparency, mainly due to the use of quotas. A thorough review of this system is recommended, promoting regular feedback cycles and greater employee involvement in setting objectives and assessment criteria. Evaluation should be viewed as an opportunity for development, rather than just a control mechanism, emphasizing the value of dialog and the joint construction of improvement plans.

As argued by Bustos (2021) and Meyer et al. (2002), managers should be trained in leadership and people management skills to play a more active role in motivating and retaining employees. Although the position of manager has not shown a significant moderating effect on the relationship between public policies and retention, its role in the perception of performance evaluation is relevant. Therefore, it is recommended to invest in specific training for managers, focusing on communication skills, team management, and participatory leadership, which promotes a more open and collaborative organizational culture.

Cunha and Martins (2015) emphasized the importance of integrated strategies that combine recruitment, training, evaluation, recognition and opportunities for progression to ensure lasting bonds and talent development. The challenges identified by Datar et al. (2022) and Jeswani and Sarkar (2008) indicate that HR policies must be adapted to meet employees’ expectations of flexibility, purpose, and continuous development.

6. Conclusions

The results obtained show that public policies are positively associated with workers’ intentions to remain in their jobs, albeit with varying degrees of influence.

It is worth noting that the perception of fairness in recruitment processes emerges as the most decisive factor in retention, reinforcing the importance of transparent and meritocratic practices that align with institutional values. Continuous training, although relevant, has had a moderate impact, suggesting that its potential is only fully realized when integrated into a broader strategy of professional development and enhancement. Performance appraisal, although significant, has the least relative weight, reflecting the limitations and criticisms leveled at the current model, particularly in terms of its fairness and effectiveness.

Regarding the role of managers, the results indicate that, contrary to expectations, holding a management position does not significantly influence intentions to remain in the organization, nor does it act as a relevant moderator in the relationship between public policies and retention. This finding suggests that, in the reality of the Portuguese civil service, job stability and organizational dynamics may override the impact of formal leadership.

In summary, this study confirms that talent retention in the civil service depends not only on the existence of effective people management policies, but also on their fairness, transparency, adequacy, and effective recognition of employee value.

It is concluded that the modernization of the PA, in terms of talent management and retention, requires an integrated and strategic approach, capable of responding to the expectations of workers and the challenges of a sector in constant transformation. Only in this way will it be possible to ensure a more efficient, innovative, and better-prepared PA to serve citizens with quality and commitment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.P.D.S. and A.P.-M.; methodology, S.P.D.S. and A.P.-M.; software, S.P.D.S. and A.P.-M.; validation, S.P.D.S., A.P.-M. and I.D.; formal analysis, S.P.D.S. and A.P.-M.; investigation, S.P.D.S. and A.P.-M.; resources, S.P.D.S. and A.P.-M.; data curation, S.P.D.S. and A.P.-M.; writing—original draft preparation, S.P.D.S., A.P.-M. and I.D.; writing—review and editing, S.P.D.S., A.P.-M. and I.D.; visualization, S.P.D.S., A.P.-M. and I.D.; supervision, S.P.D.S. and A.P.-M.; project administration, S.P.D.S. and A.P.-M.; funding acquisition, A.P.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study since all participants (before answering the questionnaire) needed to read the informed consent portion and agree to it. This was the only way they could complete the questionnaire. Participants were informed about the purpose of this study and that their responses would remain confidential.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available because the participants’ responses are confidential.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Public Policy Scale.

Table A1.

Public Policy Scale.

| Dimension | Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neither Agree nor Disagree | Agree | Strongly Agree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recruitment | 1. Do you consider the recruitment process for management positions to be appropriate and transparent? | ||||

| 2. Is mobility between organizations swift and facilitated by leadership and organizations? | |||||

| 3. Are the recruitment competitions provided by organizations generally swift and appropriate? | |||||

| Training | 1. Is the training provided by the organization appropriate for the performance of their duties? | ||||

| 2. Is the training provided chosen by the employees and not imposed by the organization? | |||||

| 3. Do organizations generally value training that is appropriate for the position held? | |||||

| Evaluation | 1. Do I encourage my team to participate in setting objectives within IPESPA? | ||||

| 2. Are there initiatives to promote the involvement of managers and employees in the self-assessment of the organization within IPESPA? | |||||

| 3. Does the organization conduct annual employee satisfaction surveys? | |||||

Table A2.

Retention Intentions Scale.

Table A2.

Retention Intentions Scale.

| Does Not Apply | Applies Slightly | Applies Partially | Applies Greatly | Applies Completely |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. I plan to remain with this organization for as long as possible. | ||||

| 2. It is very likely that I will leave this organization in the near future. (R) | ||||

| 3. I plan to leave this organization as soon as possible. (R) | ||||

| 4. I plan to leave this organization in the near future. (R) | ||||

| 5. I am currently actively seeking another job in another organization. (R) | ||||

| 6. If I can, I will remain in this organization for as long as possible. | ||||

Legend: R = Reversed.

References

- Ajzen, I. (2012). The theory of planned behavior. In P. Lange, A. Kruglanski, & T. Higgins (Eds.), The handbook of theories of social psychology (pp. 438–459). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Amaral, F. (2014). A administração pública: Conceito de administração. Curso de Direito Administrativo, 1(3), 1–58. [Google Scholar]

- Banco de Portugal. (2024). Boletim económico—Junho 2024. Available online: https://www.bportugal.pt/napp_wrapper/130018 (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- Bártolo-Ribeiro, R. (2018). Desenvolvimento e validação de uma escala de intenções de saída organizacional. In M. Pereira, I. M. Alberto, J. J. Costa, J. T. Silva, C. P. A. Albuquerque, M. J. S. Santos, M. P. Vilar, & T. M. D. Rebelo (Eds.), Diagnóstico e avaliação psicológica: Atas do 10º congresso da AIDAP/AIDEP (pp. 378–390). AIDAP/AIDEP. [Google Scholar]

- Benson, G. (2006). Employee development, commitment, and intention to turnover: A test of ‘employability’ policies in action. Human Resource Management Journal, 16(2), 173–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilhim, J. (2021, June 25). As reformas da administração pública em Portugal nos últimos vinte anos. Observatório Almedina. Available online: https://observatorio.almedina.net/index.php/2021/06/25/as-reformas-da-administracao-publica-em-portugal-nos-ultimos-vinte-anos/ (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Blau, P. M. (1964). Justice in social exchange. Sociological Inquiry, 34, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozeman, D., & Perrewé, P. (2002). The effect of item content overlap on organizational commitment questionnaire–turnover cognitions relationships. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustos, E. (2021). Organizational reputation in the public administration: A systematic literature review. Public Administration Review, 81(4), 731–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustos, E. (2023). The effect of organizational reputation on public employees’ retention: How to win the “war for talent” in constitutional autonomous agencies in Mexico. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 43(4), 794–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, M. (2016). Public sector leaders’ strategies to improve employee retention [Ph.D. thesis, Walden University]. [Google Scholar]

- Chiavenato, I. (2014). Gestão de pessoas: O novo papel dos recursos humanos nas organizações. Manole. Available online: https://shre.ink/eDsK (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Cho, Y., & Lewis, G. (2012). Turnover intention and turnover behavior: Implications for retaining federal employees. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 32(1), 4–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, N. C., & Martins, S. M. (2015). Retenção de talentos frente às mudanças no mercado de trabalho: Uma pesquisa bibliográfica. Getec, 4(8), 90–109. Available online: https://revistas.fucamp.edu.br/index.php/getec/article/view/705 (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- Datar, A., Ruiz, J., O’Leary, J., Agarwal, S., & Sanwardeker, R. (2022). Winning the war for talent in government. Deloitte Insights. Available online: https://www.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/industry/government-public-sector-services/talent-war-government.html (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Delisle, S., & Rinfret, N. (2006). L’étude du leadership dans le secteur public: État de la situation. Capitale. Available online: https://shre.ink/eDsL (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Direção Geral da Administração e do Emprego Público (DGAEP). (2018a). Estrutura da administração pública. Available online: https://shre.ink/eDsb (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Direção Geral da Administração e do Emprego Público (DGAEP). (2018b). Síntese estatística do emprego público, 4.º Trimestre 2017. Available online: https://shre.ink/eDse (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Direção Geral da Administração e do Emprego Público (DGAEP). (2025). Recrutamento e seleção na administração pública. Available online: https://shre.ink/eDsD (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Fahim, M. (2018). Strategic human resource management and public employee retention. Review of Economics and Polítical Science, 3(2), 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fialho, E., Sousa, M. J., & Moreira, A. (2023, November 23–24). Public administration leadership and public policies. 19th European Conference on Management Leadership and Governance (Vol. 19, pp. 136–146), London, UK. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fialho, E., Sousa, M. J., & Palma-Moreira, A. (2025). Validation of a public policy perception scale in the context of the Portuguese public administration. European Journal of Development and Training, ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goleman, D. (2000). Leadership that gets results. Harvard Business Review, 78(2), 78–90. Available online: https://hbr.org/2000/03/leadership-that-gets-results (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Gouldner, A. W. (1960). The norm of reciprocity: A preliminary statement. American Sociological Review, 25, 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Governo de Portugal. (2024). Balanço final do XXIII governo institucional. Available online: https://shre.ink/eDsQ (accessed on 23 November 2024).

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed.). Sage Publications Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A. F. (2022). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2013-21121-000 (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Hofstede, G. (1991). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind. McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Administração (INA). (2018). Percursos profissionais na administração pública: Carreiras e competências. Available online: https://www.adcoesao.pt/wp-content/uploads/resumoinasessao2.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2025).

- Instituto Nacional de Administração (INA). (2024). O essencial do regime da formação profissional. Available online: https://www.ina.pt/formacao/coordenacao-da-formacao/legislacao-aplicavel/o-essencial-do-regime-da-formacao-profissional/ (accessed on 4 February 2025).

- Jeswani, S., & Sarkar, S. (2008). Integrating talent engagement high performance and to as a strategy retention. Asia-Pacific Business Review, 5(4), 14–23. Available online: https://shre.ink/eDBi (accessed on 15 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Jöreskog, K. G., & Sörbom, D. (1993). LISREL8: Structural equation modelling with the SIMPLIS command language. Scientific Software International. [Google Scholar]

- Kellough, E., & Osuna, W. (1995). Cross-agency comparisons of quit rates in the federal service: Another look at the evidence. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 15(4), 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei n.º 2/2004, de 15 de janeiro, da Assembleia da República. Diário da República: Série I-A, n.º 12, de 15/01/2004, pp. 293–301. (2004). Available online: https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/detalhe/lei/2-2004-603476 (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Lei n.º 35/2014, de 20 de junho, da Assembleia da República. Diário da República: Série I, n.º 117, de 20/06/2014, pp. 3220–3304. (2014). Available online: https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/detalhe/lei/35-2014-25676932 (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Lei n.º 128/2015, de 3 de setembro, da Assembleia da República. Diário da República: Série I, de 03/09/2015, pp. 6892–6897. (2015). Available online: https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/detalhe/lei/128-2015-70179157 (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Lei n.º 86/2016, de 29 de dezembro, do Ministério das Finanças. Diário da República: Série I, nº 249, de 29/12/2016, 5142. (2016). Available online: https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/detalhe/decreto-lei/86-a-2016-105658704 (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Madureira, C. (2015). A reforma da administração pública central no Portugal democrático: Do período pós-revolucionário à intervenção da troika. Revista Administração Pública, 49(3), 547–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madureira, C. (2020). A reforma da administração pública e a evolução do Estado-Providência em Portugal: História recente. Ler História, 76, 179–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCallum, R., Browne, M., & Sugawara, H. (1996). Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structural modelling. Psychological Methods, 1, 130–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J., Stanley, D., Herscovitch, L., & Topolnytsky, L. (2002). Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: A meta-analysis of antecedents, correlates, and consequences. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 61, 20–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moitinho, G. (2011). Renumeração, benefícios, e a retenção de talentos nas organizações. Revista Digital de Administração, 1(1), 1–8. Available online: https://shre.ink/eDBS (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Moreira, A., & Coutinho, D. (2022). Turnover e os desafios nos processos de recrutamento, seleção e treinamento de novos colaboradores: Um estudo de caso em uma empresa de comunicação. Revista Científica Multidisciplinar Núcleo do Conhecimento, 7(12), 130–147. Available online: https://shre.ink/eDBM (accessed on 15 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Nunes, A., Martins, G., & Mendonça, J. (2021). A retenção de talentos e o novo normal de recursos humanos. Id on line Revista de Psicologia, 15(58), 391–409. Available online: https://idonline.emnuvens.com.br/id/article/view/3335 (accessed on 5 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2017). Government at a glance. OECD. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2021). The OECD framework for digital talent and skills in the public sector. OECD. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, J. L., & Wise, L. R. (1990). The Motivational bases of public service. Public Administration Review, 50(3), 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, P. (2025, February 12). A administração pública em crise: É hora de repensar a gestão de talento. Jornal Económico. Available online: https://shre.ink/eDBQ (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reis, M. F. T. (2015). Avaliação de desempenho e motivação dos recursos humanos: Caso da CIM Alto Minho [Master’s thesis, Universidade do Minho]. RepositóriUM. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/1822/37881 (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Schein, E. H. (2010). Organizational culture and leadership. Jossey-Bass. Available online: https://books.google.pt/books?id=Mnres2PlFLMC&printsec=frontcover&hl=pt-PT#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Silva, E., Costa, S., Amorim, D., Borges, M., & Chaves, P. (2023). Retenção de talentos nas organizações. Getec, 12(40), 4–18. Available online: http://revistas.fucamp.edu.br/index.php/getec/article/view/3059 (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- Silva, L., & Dinis, E. (2021). Retenção de talentos e sua importância na gestão de recursos humanos. Available online: https://iesfma.com.br/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/RETENCAO-DE-TALENTOS-e-sua-importancia-na-gestao-de-recursos-humanos.-SILVA-Lidia-de-Sousa.-2021.pdf (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Trochim, W. (2000). The research method knowledge base. Available online: https://shre.ink/eDpE (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Tupari, E., Freitas, H., & Souza, F. (2024). Gestão de recursos humanos na administração pública: Estratégias para atração e retenção de talentos. Ciências Sociais Aplicadas, 29(140), 18–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).