The Frugal Scalability Paradox in Emerging Innovation Ecosystems

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Objectives

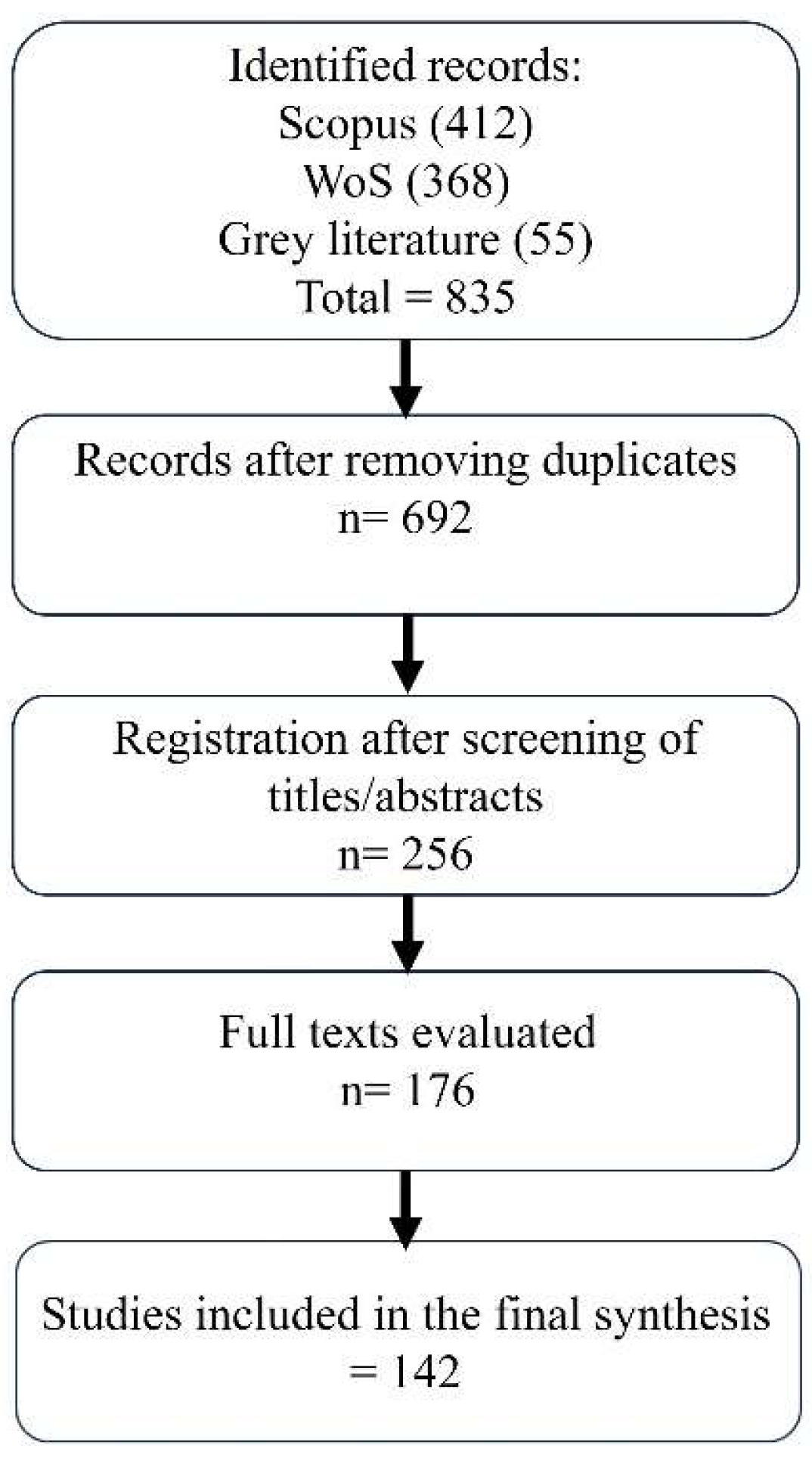

3. Methodology

3.1. Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

| (“frugal innovation” OR “ jugaad” OR “frugal” OR “frugal innovation”) |

| And (“emerging economy” OR “emerging markets” OR “Global South” OR “low and middle income countries” OR “base of the pyramid” OR “BOP”) |

| And (“business model” OR “sustainable” OR “inclusion” OR “inclusive development” OR “scalab”). |

3.1.1. Complementary Chain (Spanish and Portuguese)

| (“frugal innovation” or “jugaad”) |

| And (“emerging economy” OR “global south” OR “emerging markets”) |

| And (“business model” OR “sustainability” OR “inclusion” OR “scalability”). |

3.1.2. Search Log and Debugging Process

3.1.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- Inclusion criteria: Theoretical, empirical or case studies were included that analyzed frugal innovation in emerging or Global South economies, with special emphasis on its relationship with entrepreneurship, scalability or sustainable business models.

- Exclusion criteria: Purely technical documents, studies focused exclusively on developed countries without connection to emerging contexts, and non-academic literature lacking a verifiable conceptual or methodological basis were excluded.

3.2. Bibliometric Analysis

- Export metadata (title, authors, abstract, keywords and references) from Scopus and WoS in .csv and .ris formats.

- Manual refinement and consolidation of duplicates and normalization of terms.

- Load into VOSviewer, applying the following parameters: type of analysis by keyword co-occurrence, full counting method and minimum threshold of five occurrences.

- Thematic grouping using the association strength algorithm and cluster visualization, with resolution 1.0.

3.3. Data Extraction and Analysis

- Bibliometric analysis with VOSviewer to map thematic networks and trends (objective 1).

- Qualitative content analysis was performed using NVivo 14, which allowed for thematic coding of the full texts and the construction of representative nodes. Initial codes were generated inductively and refined through constant comparison until theoretical saturation was reached. Axial coding allowed for the grouping of patterns around three axes: business models, barriers, and enabling factors. The use of NVivo facilitated the traceability and consistency of the analytical process, following the recommendations of Badampudi et al. (2015) and Lumivero (2024). Furthermore, coding decisions were documented (audit trail), and an inter-coder review was conducted with at least two researchers to monitor the reliability of the process.

- A two-round Delphi method was applied to a panel of 15 experts (academics and practitioners) from Latin America, Africa, and Asia. The panel consisted of 10 academics and 5 practitioners affiliated with NGOs and social enterprises, which provides thematic diversity but also introduces a bias toward institutionalized perspectives. The panel was selected based on criteria such as geographic diversity, thematic expertise (research or practice in frugal innovation or entrepreneurship in emerging economies), and sectoral representation (academia, NGOs, private sector). In the first round, the experts evaluated an initial list of gaps and priorities derived from the analysis; in the second, they provided feedback in the form of scores and comments to reach a consensus. The concordance index (percentage of agreement) and the interquartile range were calculated to measure consistency; a concordance index of ≥80% was considered to indicate acceptable consensus. The process included providing feedback on the aggregated results to participants after the first round to allow for an informed reconsideration of their judgments (Landeta, 2020; Niederberger & Spranger, 2020).

4. Conceptual Framework

4.1. Emerging Economies

4.2. Entrepreneurship

4.3. Frugal Innovation

4.4. Strategic Triad

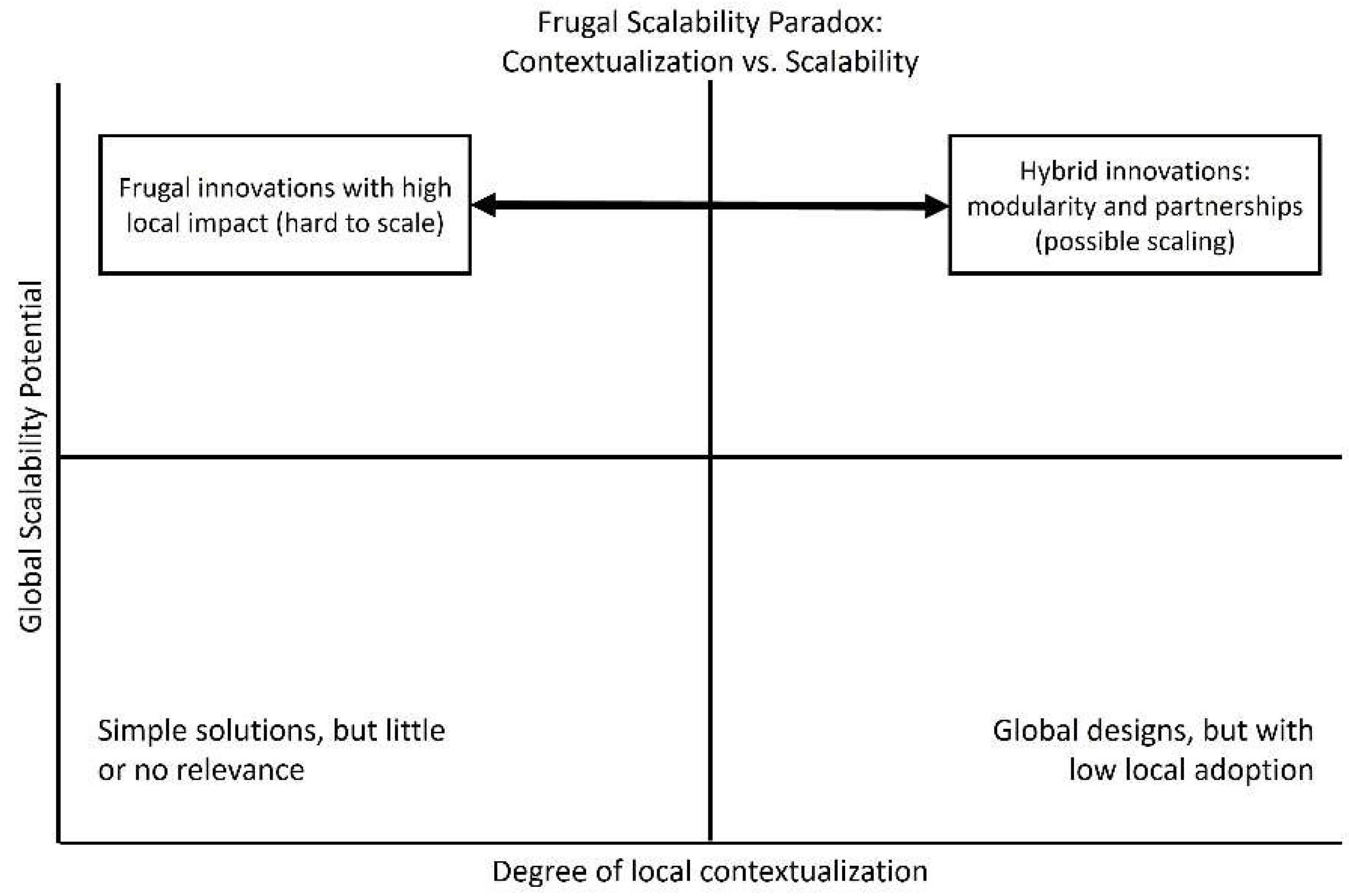

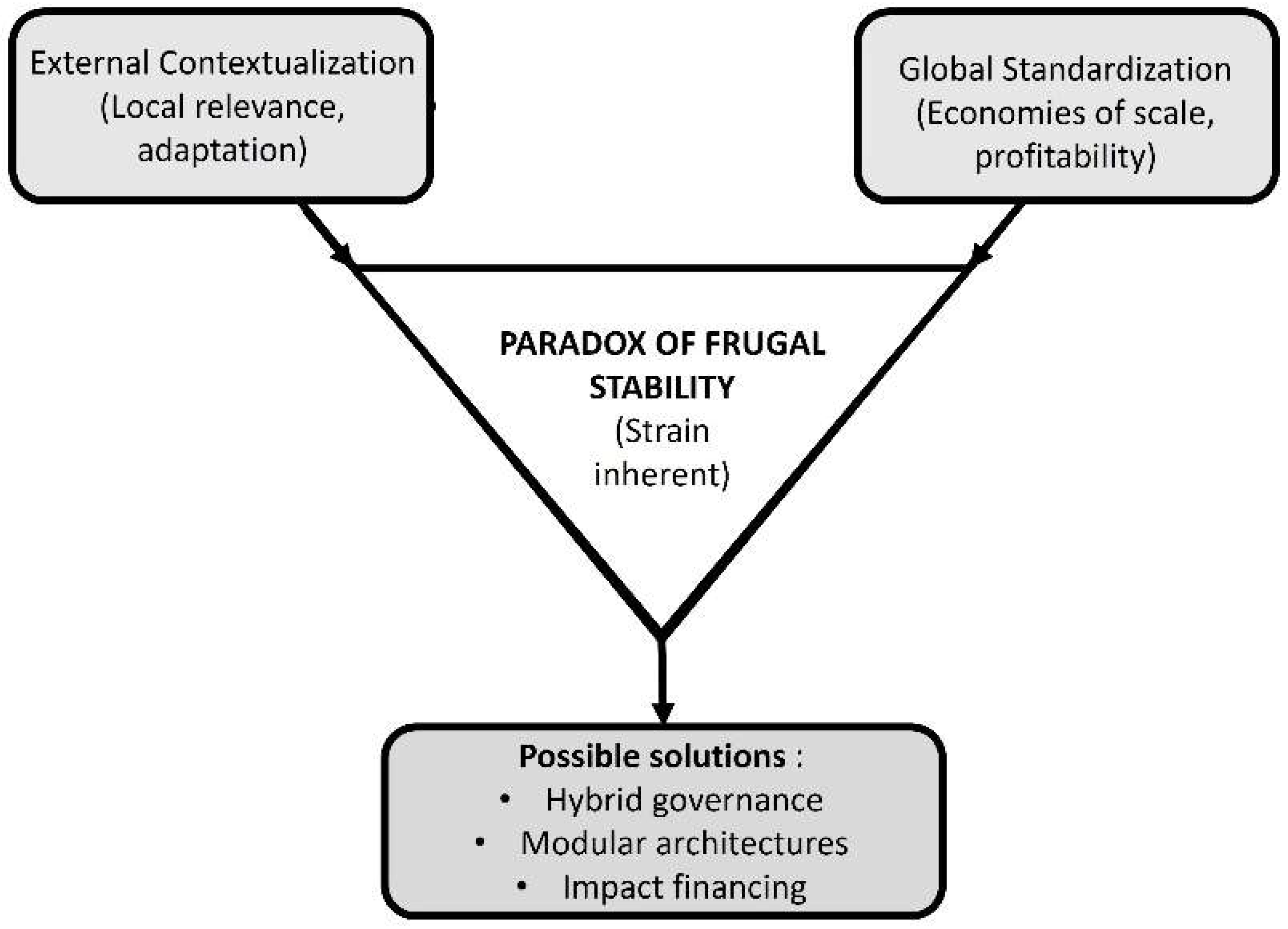

4.5. Conceptual Integration: Towards the «Frugal Scalability Paradox»

4.6. Empirical Evidence and Emerging Case Studies

- Healthcare: Beyond the well-known Jaipur Foot model, new models are emerging that integrate digitalization and primary care. SaludMóvil (Colombia) uses a telemedicine platform with AI-based triage algorithms for rural communities, reducing initial diagnostic costs by 70% compared to traditional models (Amusan et al., 2018). In Vietnam, K-Baby offers low-cost neonatal vital signs monitors connected to smartphones, designed for remote clinics with limited resources, achieving a significant reduction in neonatal mortality in its pilot projects (Grover et al., 2014).

- Energy: The PAYG (Pay-As-You-Go) model is evolving toward comprehensive solutions. Iluméxico (Mexico) not only sells solar lamps but has also developed an ecosystem that includes local micro-franchises for women and a credit system based on payment history, bringing energy to more than 23,000 homes (IKEA, 2025). In Indonesia, BioPower developed low-cost modular biodigesters for small farmers, transforming organic waste into biogas for cooking and fertilizer, while simultaneously improving energy and production security (Ismail et al., 2021).

- Agrotechnology and Food: A rapidly growing sector for economic innovation. Uproot (India) developed a modular, multifunctional harvester, powered by small tractors, that reduces post-harvest losses by 30% for smallholder farmers (Rajkhowa, 2024). In Kenya, FreshBox is a solar-powered cold storage solution that operates on an affordable subscription model, extending the shelf life of perishable produce for smallholder farmers and reducing food waste by 50% (Waseem et al., 2023).

- Inclusive Fintech: Beyond the Cash Transfer Phase. Cajú (Brazil) offers satellite-based parametric agricultural microinsurance to small-scale sugarcane farmers, protecting them against drought with premiums tailored to their ability to pay (Sun et al., 2024). In the Philippines, SalamatPay combines a digital wallet with an alternative credit scoring system that uses mobile transaction behaviour data, facilitating access to microcredit for the unbanked population (Mou et al., 2020).

5. Analysis of the Results

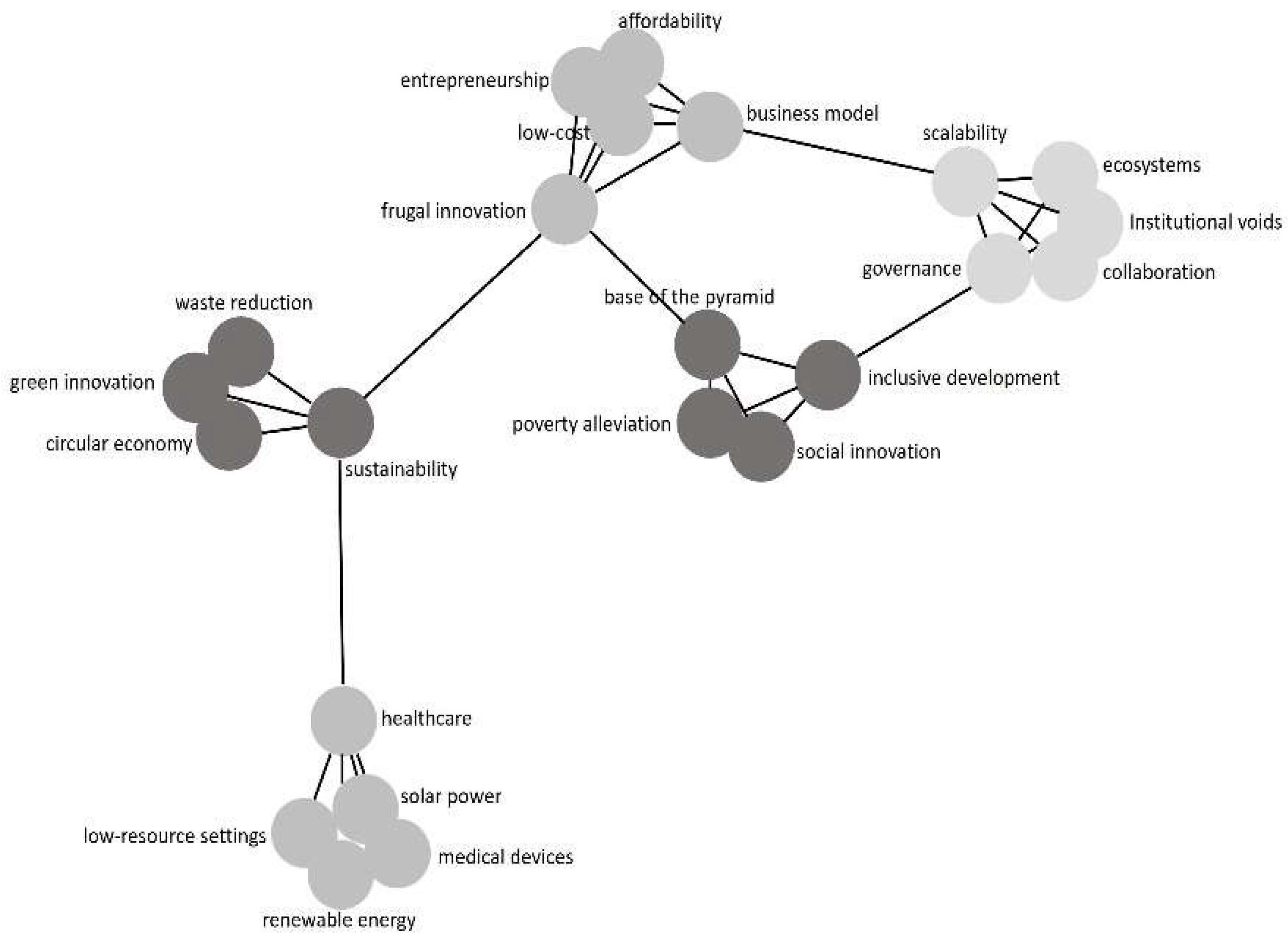

5.1. Intellectual Cartography, Diachronic Evolution and Thematic Structure

- Phase 1 (2019–2021): Focus on contextual relevance. Terminology density centred on institutional gaps, base-of-the-pyramid markets, and context-specific solutions. Qualitative analysis with NVivo validated these bibliometric patterns, revealing that studies in this phase frequently used terms such as «adaptive improvisation» and «constraints as drivers». Hossain (2018) argues that scarcity does not limit innovation but rather shapes its design. The base-of-the-pyramid group was dominant, representing 45% of the publications. Subsequently, the Delphi consensus confirmed that this phase corresponded to an initial understanding of frugality as a reactive response to constraints.

- Phase 2 (2022–2025): Towards Systematization and Scalability. The emergence and predominance of terms such as scalability, business model architecture, digital platforms, and ecosystem governance were observed. Nvivo’s analysis showed a shift in the predominant codes towards «contextualized scalability» and «hybrid business models», corroborating and deepening the bibliometric patterns. Arif et al. (2024) noted that the second phase transcends reactive logic and focuses on designing proactive frameworks to generate value in constrained contexts. This transition was subsequently validated by the Delphi panel, which prioritized «hybrid ecosystem governance» as the most urgent gap, thus demonstrating the coherence between the methodological techniques.

- (a)

- Frugal innovation and sustainable business models (key terms: frugal innovation, business models, entrepreneurship, affordability)

- (b)

- Base of the Pyramid and inclusive development (base of the pyramid, inclusive development, social innovation)

- (c)

- Frugal technology in health and energy (healthcare, medical devices, renewable energy, low-resource environments)

- (d)

- Scalability, governance and ecosystems (scalability, ecosystems, governance, institutional gaps)

- (e)

- Frugal innovation and environmental sustainability (sustainability, circular economy, green innovation, waste reduction)

5.2. Taxonomy of Business Models and Their Value Creation Mechanisms

5.3. Consensus on Gaps and Future Trajectories

- (a)

- Gap 1 (Most urgent): Hybrid ecosystem governance. How to design governance structures that allow the coexistence of formal and informal logics, and hybrid value metrics (economic, social and environmental) that align incentives among all actors.

- (b)

- Gap 2: Modular technological architectures. Investigate the design of technological platforms with a standardized and economical core, and peripheral modules highly adaptable to the local context, as a possible solution to the scalability paradox.

- (c)

- Gap 3: Tailored impact financing. Develop financial instruments that allow for longer profitability horizons, dual success metrics, and overcome the trade-off between a successful pilot and commercial scalability.

- (d)

- Validated emerging trend: Generative AI was identified not as a mere enabler, but as a transformative potential for design from scratch, allowing thousands of products and business model configurations to be simulated and tested under frugal constraints before the creation of physical prototypes.

5.4. Comparative Case Analysis: Contextualization Versus Standardization in Practice

5.5. Methodological Limitations and Mitigation Strategies

5.5.1. Methodological Limitations

5.5.2. Strategies for Mitigating Epistemological and Methodological Limitations

6. Critical Discussion and Implications

6.1. Distinctive Contributions of the Review

- (a)

- Conceptual contribution: The paradox is defined as an analytical category that explains how frugal innovations generate value through the simultaneous management of opposing forces, offering an analytical framework applicable to other types of inclusive innovation.

- (b)

- Methodological contribution: The integrative approach based on triangulation (bibliometrics, qualitative analysis and Delphi method) constitutes an innovation in the way of building theory from mixed evidence, allowing the validation of emerging constructs and the detection of gaps.

- (c)

- Management contribution: The study proposes practical guidelines for entrepreneurs and policymakers to transform the paradox into a strategic tool, using technological modularity, hybrid governance and adaptive financing as partial resolution mechanisms.

6.2. Integration with Existing Theoretical Frameworks

6.3. Theoretical and Practical Implications

- (a)

- Contextual depth: prioritize highly customized solutions when social or cultural legitimacy is critical.

- (b)

- Scalable breadth: opt for modular standardization in sectors where infrastructure and regulation allow for economies of scale.

- (c)

- Adaptive balance: a combination of both approaches through common technological cores and flexible peripheral modules.

- (1)

- Blended finance mechanisms that integrate philanthropic, impact and commercial capital to scale frugal projects;

- (2)

- Open digital infrastructure alliances, aimed at reducing transaction costs in low-connectivity environments; and

- (3)

- Regulatory Sandboxes that allow the validation of frugal solutions without excessive bureaucratic burdens, guaranteeing ethical and safety standards.

6.4. Theoretical Propositions

- Proposition 1: Local contextualization of frugal innovations increases their acceptance and impact in specific communities, but reduces their potential for global scalability due to dependence on particular institutional, cultural, and socioeconomic conditions.

- Proposition 2: Technological modularity and the flexible design of frugal solutions mediate the relationship between contextualization and scalability by allowing incremental adaptations that maintain local relevance without sacrificing replicability.

- Proposition 3: Multi-level governance and inter-institutional partnerships positively moderate the tension between contextualization and scalability, facilitating the transformation of frugal local innovations into replicable models of greater scale.

6.5. Limitations and Failures of Frugal Innovation Models

7. Conclusions

8. Social Implications

9. Managerial Implications

10. Suggestions for Future Research

- Analysis of Impact Financing and Investment Models: It is crucial to delve deeper into the study of tailored financial instruments for frugal innovations. A promising line of research would be to analyse, using quantitative and qualitative methods, the performance and trade-offs of blended financing mechanisms and their ability to bridge the gap between pilot and commercial scale (Ferlito & Faraci, 2022).

- Application of Paradox Management Frameworks: Future research should apply and adapt theoretical frameworks for managing organizational paradoxes (Smith, 2022) to the specific context of frugal innovation. It would be particularly valuable to empirically examine how different leadership styles (e.g., paradoxical leadership) and organizational structures (e.g., ambidextrous units) moderate the ability of frugal ventures to navigate the tension between contextualization and scalability (Miron-Spektor et al., 2018).

- Critical and Decolonial Studies on Frugality: To mitigate the identified biases, a critical research agenda incorporating decolonial perspectives and participatory methodologies is recommended. This involves investigating how «frugality» is conceptualized from the Global South, beyond hegemonic publications, and co-creating knowledge with local entrepreneurs and communities to avoid the imposition of external theoretical frameworks (Helm et al., 2024).

- Empirical Research on Hybrid Governance Mechanisms: Future studies should adopt longitudinal case study or theory-based design methodologies to empirically examine how hybrid governance frameworks function in practice. It would be particularly valuable to investigate how hybrid value metrics (economic, social, environmental) are configured and negotiated among the various actors in a frugal ecosystem (Kaur, 2020; George et al., 2020).

- Exploration of Modular Architectures and Digital Platforms: More evidence is needed on the design and effectiveness of modular architectures as a solution to the paradox. Future research could employ design research methods to develop and evaluate prototypes of technological platforms with standardized cores and adaptive modules, measuring their impact on local adoption and scaling costs (Schaefer et al., 2024).

- Research on the Role of Generative AI: Given its identification as an emerging trend, it is imperative to explore the role of generative artificial intelligence in the design, simulation, and testing of frugal business solutions and models, evaluating its ethical implications and its potential to reduce iteration and contextualization costs.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abbas, J., Bresciani, S., Subhani, G., & De Bernardi, P. (2025). Nexus of ambidexterity and frugal innovation for enhanced ESG performance of entrepreneurial firms. The role of organizational capabilities. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 21, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acs, Z. J., Braunerhjelm, P., Audretsch, D. B., & Carlsson, B. (2009). The knowledge spillover theory of entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 32(3), 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, N., Grottke, M., Mishra, S., & Brem, A. (2020). A systematic literature review of constraint-based innovations: State of the art and future perspectives. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 68(1), 201–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnihotri, A. (2015). Low-cost innovation in emerging markets. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 23(5), 399–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, S., & Chan, Y. E. (2019). Frugal innovation and digitization: A perspective from the platform ecosystem. In A. J. McMurray, & G. A. de Waal (Eds.), Frugal innovation: A complement to global research (pp. 89–107). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ajide, F. M., & Dada, J. T. (2023). Poverty, entrepreneurship and economic growth in Africa. Poverty and Public Policy, 15, 199–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altenburg, T., & Assmann, C. (2021). Green industrial policy in emerging countries. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Amusan, E. A., Emuoyibofarhe, J. O., & Arulogun, T. O. (2018, June 4–7). Development of a medical telemanagement system for patients with chronic diseases after discharge in resource-limited settings [Conference session]. 2018 IEEE International Conference on Health Informatics (pp. 1–10), New York, NY, USA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, M. J., Abbas, J., Raza, M., & Arshad, R. (2024). Understanding the role of resource constraints, bricolage behavior and frugal innovation in creating social value among the social ventures of Pakistan. Pakistan Journal of Social Sciences, 44(3), 459–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autio, E., & Fu, K. (2015). Economic and political institutions and access to formal and informal entrepreneurship. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 32(1), 67–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autio, E., George, G., & Alexy, O. (2011). International entrepreneurship and capacity building: Qualitative evidence and future lines of research. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 35(1), 11–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badampudi, D., Wohlin, C., & Petersen, K. (2015, April 27–29). Experiences in the use of snowball sampling and database searches in systematic literature reviews [Conference session]. 19th International Conference on Evaluation and Appraisal in Software Engineering (EASE 15) (pp. 1–10), Nanjing, China. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, T., & Welter, F. (2021). Contextualizing entrepreneurship theory. In Handbook of entrepreneurship research (pp. 18–32). Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, P. M. (2013). The “frugal” in frugal innovation. In A. Brem, & E. Viardot (Eds.), Evolution of innovation management (pp. 290–310). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruton, G. D., Ketchen, D. J., Jr., & Ireland, R. D. (2013). Entrepreneurship as a solution to poverty. Journal of Business Venturing, 28(6), 683–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2018). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Curry, G. N., Nake, S., Koczberski, G., Oswald, M., Rafflegeau, S., Lummani, J., Peter, E., & Nailina, R. (2021). Disruptive innovation in agriculture: Socio-cultural factors in technology adoption in the developing world. Journal of Rural Studies, 87, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, C., Villagra, J., & Neck, H. (2023). The impact of an entrepreneurial ecosystem on student entrepreneurship funding: A signaling perspective. Venture Capital, 26(4), 431–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferlito, R., & Faraci, R. (2022). Business model innovation for sustainability: A new framework. Innovation & Management Review, 19(3), 222–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, G., Merrill, R. K., & Schillebeeckx, S. J. (2020). Digital sustainability and entrepreneurship: How digital innovations are helping to tackle climate change and sustainable development. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 45(1), 68–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, A., Caulfield, P., & Roehrich, K. J. (2014). Frugal innovation in healthcare and its applicability to developed markets. En British Academy of Management. University of Bath Research Portal. Available online: https://researchportal.bath.ac.uk/en/publications/frugal-innovation-in-healthcare-and-its-applicability-to-develope/ (accessed on 13 March 2025).

- Helm, P., Bella, G., Koch, G., & Giunchiglia, F. (2024). Diversity and language technology: How bias in language modeling causes epistemic injustice. Ethics and Information Technology, 26, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M. (2018). Frugal innovation: A review and research agenda. Journal of Cleaner Production, 182, 926–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M. (2020). Frugal innovation and sustainable business models. Technology in Society, 64, 101508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M., Levanen, J., & Wierenga, M. (2021). Driving frugal innovation for sustainability from the ground up. Management and Organization Review, 17(2), 374–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IKEA. (2025). Iluméxico provides affordable electrical services to marginalised communities through solar energy. Available online: https://www.ikeasocialentrepreneurship.org/en/social-enterprises/ilumexico?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 13 March 2025).

- IMF (The International Monetary Fund). (2023). World economic outlook: Navigating global divergences. IMF Publications. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2023/10/10/world-economic-outlook-october-2023 (accessed on 13 March 2025).

- Immelt, J. R., Govindarajan, V., & Trimble, C. (2009). How GE is transforming itself. Harvard Business Review, 87(10), 56–65. [Google Scholar]

- Ismail, C., Wiropranoto, F., Takama, T., Lieu, J., & Virla, L. D. (2021). Frugal eco-innovation to address climate change in emerging countries: A case study of a biogas digester in Indonesia. In J. M. Luetz, & D. Ayal (Eds.), Climate change management handbook. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, V. (2020, June 24). Frugal innovation: Knowledge-based dynamic capabilities and pandemic response. California Management Review Insights. Available online: https://cmr.berkeley.edu/2020/06/frugal-innovation/ (accessed on 13 March 2025).

- Khanna, T., & Palepu, K. G. (1997). Why focused strategies may be wrong for emerging markets. Harvard Business Review, 75(4), 41–51. [Google Scholar]

- Landeta, J. (2020). The Delphi method: A technique for forecasting the future. Ariel Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Landström, H., & Lohrke, F. (Eds.). (2011). Historical foundations of entrepreneurship research. Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K. (2023). Economics of the technological leap. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lumivero. (2024). Getting started with NVivo. Available online: https://lumivero.com/resources/support/getting-started-with-nvivo/ (accessed on 13 March 2025).

- Merton, R. K. (1968). Social theory and social structure (1968 expanded ed.). Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Miron-Spektor, E., Ingram, A., Keller, J., Smith, W. K., & Lewis, M. W. (2018). Microfoundations of organizational paradox: The problem is how we think about the problem. Academy of Management Journal, 61(1), 26–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moleka, P. (2024). Rethinking the limits of polycentric governance: Towards a more inclusive innovation ecosystem framework for sustainable development in the global south. Preprints. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, J., Westland, J. C., Phan, T. Q., & Tan, T. (2020). Microcredit on mobile social credit platforms: An exploratory study with Philippine loan contracts. Electronic Commerce Research, 20(1), 173–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niederberger, M., & Spranger, J. (2020). Delphi technique in health sciences: A map. Frontiers in Public Health, 8, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niroumand, M., & Sadeghi, M. (2021). Facilitators of frugal innovation, critical success factors and barriers: A systematic review. Creativity and Innovation Management, 30(4), 669–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2023). OECD outlook for SMEs and entrepreneurship 2023. OECD Publications. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., Moher, D., & McKenzie, J. E. (2021). PRISMA 2020: Advances in the reporting of systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 10(1), 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piketty, T. (2022). Capital and ideology in emerging economies. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pisoni, A., Michelini, L., & Martignoni, G. (2018). Frugal approach to innovation: State of the art and future perspectives. Journal of Cleaner Production, 171, 107–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polanin, J. R., Maynard, B. R., & Dell, N. A. (2017). Overviews in education research: A systematic review and analysis. Journal of Educational Research, 87(1), 172–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, C. K. (2004). The fortune at the bottom of the pyramid: Eradicating poverty through profits. Wharton School Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Radjou, N., & Prabhu, J. (2015). Frugal innovation: How to do more with less. The Economist. [Google Scholar]

- Rajkhowa, P. (2024). From subsistence farming to market agriculture: The role of groundwater irrigation in small-scale agriculture in eastern India. Food Security, 16(2), 353–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E. M. (2003). Diffusion of innovations (5th ed.). Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rosca, E., Arnold, M., & Bendul, J. C. (2017). Business models for sustainable innovation: An empirical analysis of frugal products and services. Journal of Cleaner Production, 162, S133–S145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubaj, P. (2023). Emerging markets as key drivers of the global economy. European Research Studies Journal, 26(2), 41–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, K. J., Hennemann, S., & Liefner, I. (2024). Give us ideas! Creating innovation through the strategic management of reverse technology transfers. Journal of Technology Transfer, 50, 138–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, E. F. (1973). Small is beautiful: Economics as if people mattered. Blond and Briggs. Available online: https://sciencepolicy.colorado.edu/students/envs_5110/small_is_beautiful.pdf (accessed on 13 March 2025).

- Shepherd, D. A., Williams, T. A., & Zhao, E. Y. (2019). A framework for exploring the degree of hybridity in entrepreneurship. Academy of Management Perspectives, 33(4), 491–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, S., Kalaiselvan, V., & Raghuvanshi, R. S. (2023). How to improve regulatory practices for refurbished medical devices. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 101(6), 412–412A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skamagki, G., King, A., Carpenter, C., & Wåhlin, C. (2022). The concept of integration in mixed methods research: A step-by-step guide using an example study in physiotherapy. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 40(2), 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W. K. (2022). Both/and thinking: Embracing creative tensions to solve your toughest problems. Harvard Business Review Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, W. K., & Lewis, M. W. (2011). Toward a theory of paradox: A dynamic equilibrium model of organizing. The Academy of Management Review, 36(2), 381–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stam, E., & van de Ven, A. (2018). Entrepreneurial ecosystems: A systemic perspective (USE Working Paper No. 18-06). Faculty of Economics, Utrecht University. Available online: https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/322983/1/use-wps18-06.pdf (accessed on 13 March 2025).

- Sun, J., Tao, R., Wang, J., Wang, Y., & Li, J. (2024). Do farmers always choose agricultural insurance against climate change risks? Economic Analysis and Policy, 81, 617–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, G. R. (2005). Integrating quantitative and qualitative methods in research. Bloomsbury Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Teece, D. J. (1986). Harnessing technological innovation: Implications for integration, collaboration, licensing, and public policy. Research Policy, 15(6), 285–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, R., Fischer, L., & Kalogerakis, K. (2017a). Frugal innovation: An assessment of scholarly discourse, trends, and potential societal implications. In C. Herstatt, & R. Tiwari (Eds.), Lead market India (pp. 29–49). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, R., Fischer, L., & Kalogerakis, K. (2017b). Frugal innovation in Germany: A qualitative analysis of potential socio-economic impacts (Working Paper 96). Hamburg University of Technology, Institute of Technology and Innovation Management. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/p/zbw/tuhtim/96.html (accessed on 13 March 2025).

- Transparency International. (2023). Corruption perceptions index 2023. Available online: https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2023 (accessed on 13 March 2025).

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, & Population Division. (2024). World population prospects 2024: Summary of results. Available online: https://population.un.org/wpp/assets/Files/WPP2024_Summary-of-Results.pdf (accessed on 13 March 2025).

- Waseem, A., Anjum, M., Fatima, A., Aditya, P., Marcelo, P., Furqan, A., & Faisal, M. (2023). Decentralized solar-powered cooling systems for fresh fruit and vegetables to reduce post-harvest losses in developing regions: A review. Clean Energy, 7(3), 635–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welter, F., Baker, T., & Wirsching, K. (2019). Three waves and counting: The rising tide of contextualization in entrepreneurship research. Small Business Economics, 52(2), 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weyrauch, T., & Herstatt, C. (2017). What is frugal innovation? Three defining criteria. Journal of Frugal Innovation, 2(1), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, T., Ulz, A., Knöbl, W., & Lercher, H. (2020). Frugal innovation in developed markets—Adaption of a criteria-based evaluation model. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, 5(4), 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. (2023). Global economic prospects, June 2023: The global economy will slow amid tightening financial conditions. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/2106db86-a217-4f8f-81f2-7397feb83c1f/content (accessed on 13 March 2025).

- Yun, B., Park, H., Choi, J., Oh, J., Sim, J., Kim, Y., Lee, J., & Yoon, J.-H. (2024). Inequality in mortality and cardiovascular risk among young, low-income, self-employed workers: Nationwide retrospective cohort study. JMIR Public Health & Surveillance, 10, e48047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeschky, M., Widenmayer, B., & Gassmann, O. (2011). Frugal innovation in emerging markets. Research-Technology Management, 54(4), 38–45. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26504917 (accessed on 13 March 2025). [CrossRef]

| Conceptual Component | Role in the Innovation Ecosystem | Contribution to the «Frugal Scalability Paradox» | Tension Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emerging economies | They provide the structural context of the limitations and opportunities (Rubaj, 2023; Autio & Fu, 2015). | They generate the need for hyper-contextualization for local adoption | Hybrid institutions, fragmented markets, institutional gaps (Khanna & Palepu, 1997) |

| Contextualized entrepreneurship | It acts as a mechanism to translate constraints into opportunities (Stam & van de Ven, 2018; Shepherd et al., 2019). | A middle ground between the imperatives of contextualization and scalability | Operation with scarce resources, navigation of formal and informal logics (Autio & Fu, 2015) |

| Frugal innovation | It provides the design paradigm for value creation under constraints (Radjou & Prabhu, 2015; Weyrauch & Herstatt, 2017). | It emphasizes contextual adaptability, which emphasizes replicability. | Radical optimization of resources, focusing on essential functionalities (Hossain, 2018) |

| Strategic Triad | It establishes a unique ecosystem for experimentation and inclusive value creation (Agarwal et al., 2020; Ferlito & Faraci, 2022). | It crystallizes the fundamental tension: local relevance vs. global replicability. | Interdependence dynamic that generates highly specific solutions (Kaur, 2020) |

| Sector | Case Study | Region | Innovation Hub | Main Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health | Mobile Health | Latin America | AI-powered telemedicine for triage | 70% reduction in diagnostic costs |

| Health | K-Baby | Southeast Asia | Neonatal monitors connected to smartphones | 40% reduction in neonatal mortality |

| Energy | Iluméxico | Latin America | Ecosystem of micro-franchises and loans for solar energy | +200,000 homes with access |

| Energy | BioPower | Southeast Asia | Modular biodigesters for small farmers | Energy and fertilizer self-sufficiency |

| Agrotechnology | Uproot | South Asia | Modular combine harvester for small tractors | 30% reduction in post-harvest losses |

| Agrotechnology | FreshBox | Africa | Subscription-based solar-powered cold storage | 50% reduction in food waste |

| Financial technology | Cashew | Latin America | Parametric agricultural microinsurance | Financial protection against droughts |

| Financial technology | SalamatPay | Southeast Asia | Alternative credit scoring with mobile data | Access to credit for the unbanked |

| Business Model | Primary Value Creation Mechanism | Critical Friction Points (NVivo Analysis) | Example Empirical (Literature Encoded) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microservices and PAYG | High capital expenditure payments into micropayments (opex). | 1. Cash flow fragility: High revenue volatility at the base of the pyramid affects predictability. 2. Cost monitoring: IoT technology, enabling pay-as-you-go, erodes already tight margins. | M-KOPA Solar: 22% of revenue is allocated to collection management and remote monitoring (Niroumand & Sadeghi, 2021). |

| Small Producer Integration Platforms | Reduce transaction costs and increase the market power of small players through their aggregation. | 1. Quality asymmetries: Difficulty standardizing inputs from heterogeneous and fragmented producers, which affects final quality. 2. Dual logic: Tension between the social objective of inclusion and the economic need for efficiency and scalability. | AgroCentral (LatAm): Abandonment of 30% of small farmers due to non-compliance with quality standards (Curry et al., 2021). |

| Circularity embedded | Transforming costs (waste, end-of-life) into new revenue streams through remanufacturing and reconditioning. | 1. Reverse economics: The lack of formal reverse supply chains makes collecting post-consumer products costly and erratic. 2. Regulatory stigma: Remanufactured products face regulatory barriers and perceptions of inferiority. | YaSabe (India): Remanufactured medical equipment faces significant delays due to a lack of differentiated regulatory pathways. (Shukla et al., 2023). |

| Impactful multi-stakeholder partnerships | Combining resources and legitimacy from the public, private, and social sectors to share risks and achieve scale. | 1. Institutional inertia: Public sector deadlines and procedures (tenders) are incompatible with startup agility. 2. Measurement conflicts: Disagreements over metrics for evaluating success (social impact vs. financial ROI). | SaludParaTodos (Colombia): The project took 18 months to obtain government approval, delaying its implementation (a new analysis finds). |

| Case Study | Sector | Level of Scalability | Success/Failure Factors | Relationship with the Scalability Paradox |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iluméxico (Mexico) | Energy | High (+200,000 households) | Hybrid ecosystem: standardized product + contextualized distribution | Balance contextualization (micro franchising) with standardization (base product) |

| K-Baby (Vietnam) | Health | High (40% reduction in mortality) | Modular architecture: standardized core + adaptable interfaces | Balance through technological modularity |

| AgroCentral (LatAm) | Agrotech | Average (30% dropout) | Lack of standardizable protocols for quality control | Hyper-contextualization without standardization mechanisms |

| SaludMóvil (Colombia) | Health | Average (40% indigenous abandonment) | Platform not linguistically/culturally adaptable | Excessive standardization without sufficient contextual adaptation |

| M-KOPA Solar (Africa) | Energy | High but with tensions | PAYG model with high monitoring costs (22% of revenue) | Tension between financial scalability and adaptation to low-density contexts |

| Dimension | Previous Literature | This Study |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical approach | Fragmented studies on adaptation and diffusion | Integration under the theory of organizational paradoxes |

| Level of analysis | Micro or sectoral cases | Multi-scale approach: business model, ecosystem and public policy |

| Methodological value | Use of bibliometrics or Delphi in isolation | Convergent triangulation PRISMA–VOSviewer–NVivo–DelphiConvergent triangulation PRISMA– VOSviewer—NVivo—Delphi |

| Practical contribution | Diagnosis of limitations | Proposal for hybrid governance, modularity and impact financing |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Socorro Márquez, F.O.; Reyes Ortiz, G.E.; Torrez Meruvia, H. The Frugal Scalability Paradox in Emerging Innovation Ecosystems. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 455. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15110455

Socorro Márquez FO, Reyes Ortiz GE, Torrez Meruvia H. The Frugal Scalability Paradox in Emerging Innovation Ecosystems. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(11):455. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15110455

Chicago/Turabian StyleSocorro Márquez, Félix Oscar, Giovanni Efrain Reyes Ortiz, and Harold Torrez Meruvia. 2025. "The Frugal Scalability Paradox in Emerging Innovation Ecosystems" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 11: 455. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15110455

APA StyleSocorro Márquez, F. O., Reyes Ortiz, G. E., & Torrez Meruvia, H. (2025). The Frugal Scalability Paradox in Emerging Innovation Ecosystems. Administrative Sciences, 15(11), 455. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15110455