Assessing Digital Governance Maturity in the Context of Municipal Resilience: The Triadic Model, Its Dimensions and Interrelations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Local Governments’ Digital Governance Maturity in the Context of Municipal Resilience

2.2. Conceptualization of the Model, Assessing Digital Governance Maturity in Local Governments

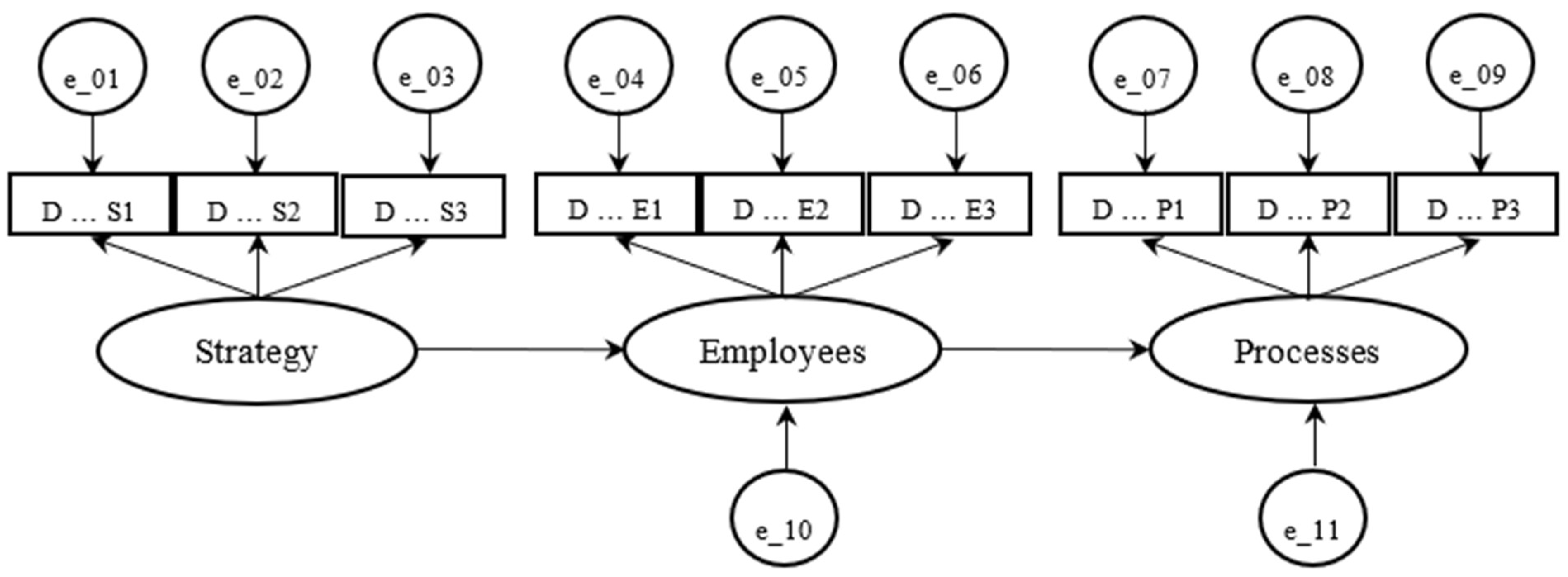

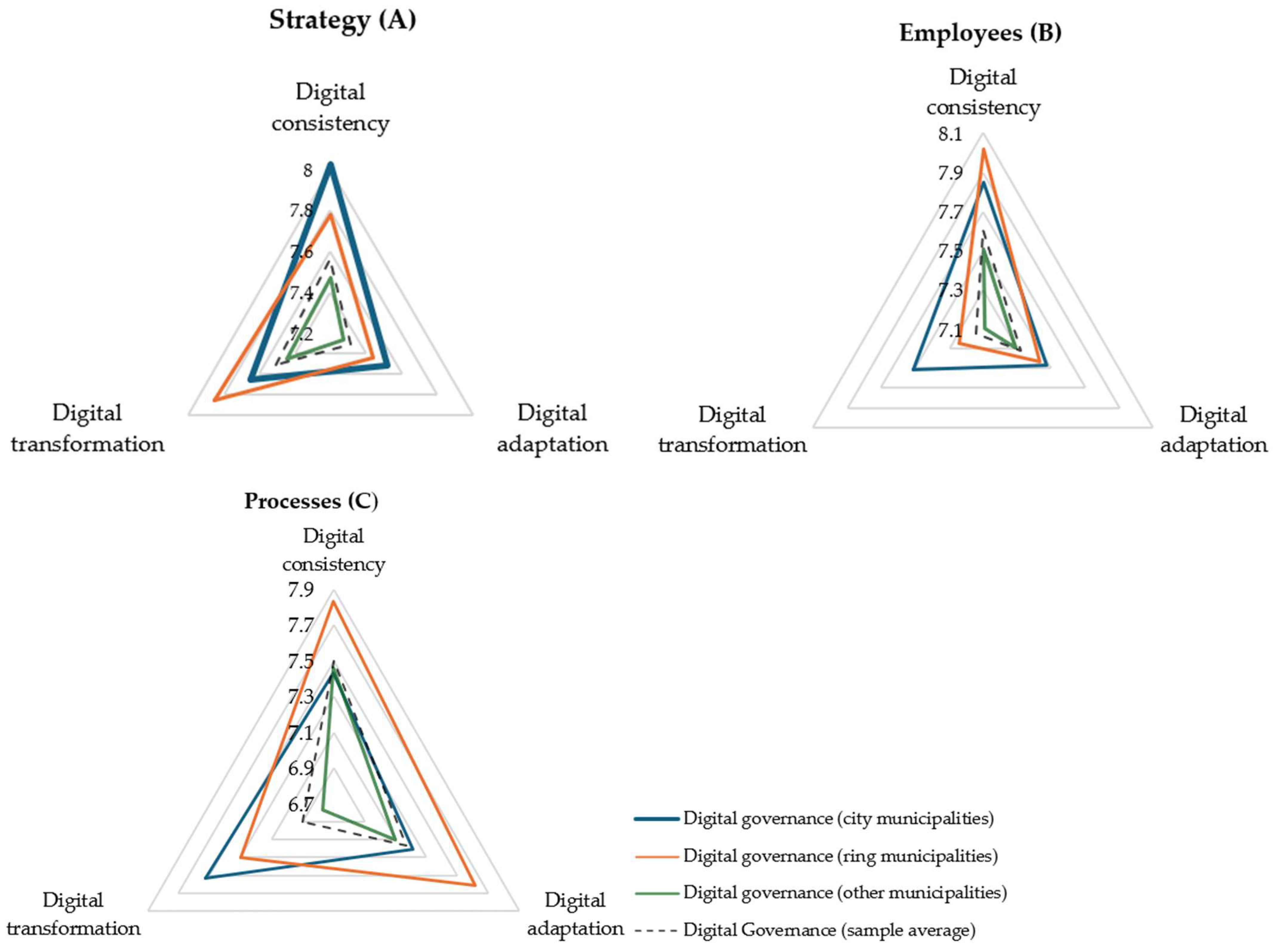

- A strategy in local governments involving digitalization establishes a clear roadmap for implementing changes as well as allocating financial resources for transformation processes, effective communication methods, and employee preparation for digitization, enhancing their capacity to respond effectively to crises and uncertainties (Tubis, 2023; Nkomo & Kalisz, 2023). Success relies on leadership commitment and managing risks to avoid strategic drift when adopting new technologies (Eom & Lee, 2022).

- Employees’ awareness, skills, motivation, continuous learning and participation are crucial for Digital Governance (Tubis, 2023; Haryanti et al., 2023). This dimension integrates both employee capacity—reflecting individual competencies, values, and adaptability—and strategic leadership, which connects human capital to organizational vision and strategic priorities. Attitudes toward digitization affect progress, while organizational (municipal) resilience emphasizes the need to develop employees’ competencies and foster collaboration (Pittaway & Montazemi, 2020; Aristovnik et al., 2024; Ahsan & Tahir, 2025).

- Processes involve procedures to achieve outcomes, focusing on digitalization, automation, and optimization (David et al., 2023; Tubis, 2023). They include performance and process management, where ICT integration enhances efficiency both internally and externally—facilitating functions like resource planning and information sharing across departments (Haryanti et al., 2023). Importantly, adaptable and agile processes—supported by ICTs—strengthen organizational resilience by enabling quick responses to crises and environmental changes (Nkomo & Kalisz, 2023).

2.3. Interrelations of Dimensions of the Model, Assessing Digital Governance Maturity in Local Governments

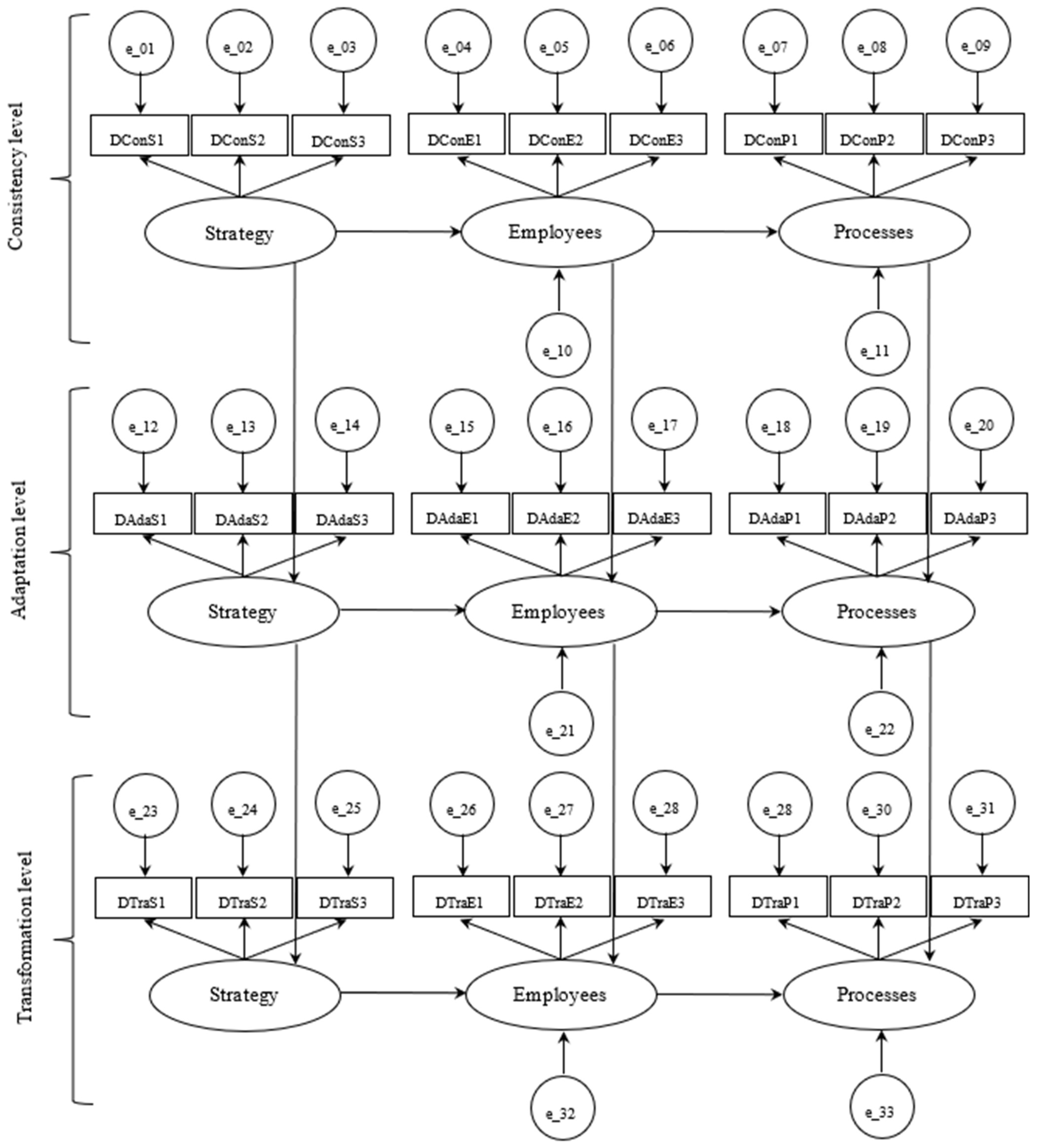

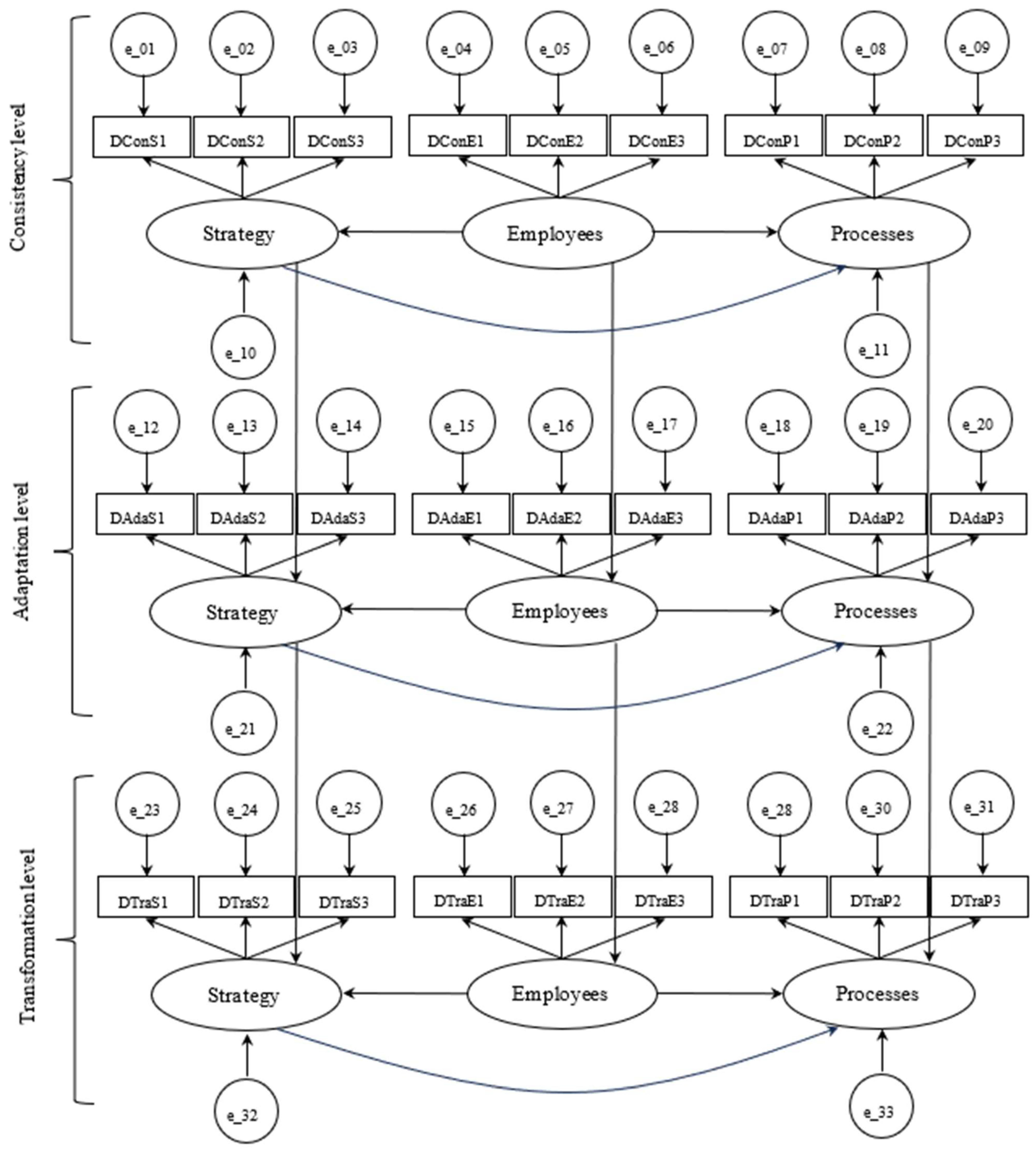

- Digital Consistency represents the lowest level of digital maturity in local governments, focusing on minimal compliance with legal digitalization mandates without efforts to innovate or modernize; it emphasizes maintaining the current state and reverting to it during crises, supporting basic operational stability amid uncertainties.

- Digital Adaptation involves proactively embracing and applying digital technologies, learning from progress of digitalization, and integrating experience into daily operations, thereby improving service quality and efficiency of local government in the context of crises.

- Digital Transformation reflects the highest maturity level, with local governments not only adopting but also leading digital initiatives, restructuring strategies, and creating innovative systems to transform internal and organizational activities, strengthening their capacity to respond effectively to crises and uncertainties (Vial, 2021; Kraus et al., 2021; He et al., 2023; Tubis, 2023; Yu et al., 2024).

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. The Research Instrument—Validation of the Items of the Triadic Model

- Digital Consistency (Con) relates to core capabilities ensuring organizations’ performance continuity, legal compliance, and stability during crises. Items (DConS1–DConS3) of the Strategy dimension focus on resource and ICT use; Employees’ items (DConE1–DConE3)—on basic digital skills and crisis training; Processes’ items (DConP1–DConP3)—on standardized planning and digital tools. The items in this category capture the resilience strategy of “bouncing back” by emphasizing continuity, risk reduction, and legal compliance. This aligns with theories suggesting that organizations first develop the capacity to maintain basic functions under adverse conditions (Boin et al., 2005).

- Digital Adaptation (Ada) involves proactive learning and incremental innovation (Fägerlind & Saha, 2016). Strategy dimension’s items (DAdaS1–DAdaS3) reflect openness to new solutions; Employees’ items (DAdaE1–DAdaE3)—on autonomous skill development; Processes’ items (DAdaP1–DAdaP3) on collaborative goal-setting and iterative learning. The items move beyond continuity to emphasize learning, openness to new tools, and proactive improvement. This resonates with the resilience strategy of “bouncing forward,” where crises accelerate adaptive changes in organizational routines (Manyena et al., 2011).

- Digital Transformation (Tra) is the highest maturity level, aiming to pioneer solutions (Mergel, 2016) and embrace high level municipal resilience (Taleb, 2012). Strategy’s items (DTraS1–DTraS3) focus on innovative service models and emerging technologies; Employees’ items (DTraE1–DTraE3)—on shared leadership and active participation; Processes’ items (DTraP1–DTraP3)—on redesigning workflows and citizen-centric e-services. Organizations adapt and reconfigure to sustain digital growth. Items emphasize structural and cultural shifts where digital initiatives drive fundamental organizational changes, thereby cultivating innovation-oriented practices that thrive on disruption rather than merely withstand it.

- Strategy reflects an organization’s conceptual and long-term vision for Digital Governance. Items (S) under this dimension capture how digital initiatives are planned, funded, and guided by leadership, even amidst uncertainties.

- Employees address the human element, including the competencies, mindsets, and leadership styles that enable or inhibit digital progress. Items (E) here emphasize the role of leaders, the development of employees’ skills, and collaborative innovation practices.

- Processes focus on the operationalization of Digital Governance, including the tools, workflows, and organizational structures in place. Items (P) measure the degree to which digital technologies are integrated into daily tasks and how these processes evolve in response to crises or uncertainties.

3.3. Models for Testing Hypotheses

4. Results

4.1. Model Testing and Validation

4.2. Evaluations of Digital Governance Maturity in Lithuanian Municipalities

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| References * | Model Name | Dimensions | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Meyerhoff Nielsen, 2017) | eGovernment benchmark model | User-centric government, transparency, cross-border mobility, and key enablers | Used by European Commission since 2002.Assessing maturity of service accessibility.Focused on service delivery |

| (Eggers & Bellman, 2015) | Deloitte’s digital government model | People, processes, preparedness. More developed version: digital strategy, leadership capabilities, workforce skills development, user focus, and cultural norms | Assessing maturity at organizational level. Focused on organizational capabilities and service delivery |

| (Joshi & Islam, 2018) | E-government maturity model for sustainable E-government services | Detailed assimilation process, streamlined services, state of art of technology, agile accessibility, awareness and trust, and quality of service. | Assessing maturity of service accessibility. Focused on service delivery. |

| (Magnusson & Nilsson, 2019) | DiMiOS: A model for government digital maturity | Digital capability (ability of the organization to sense, seize and re-configure based on digital opportunities in line with definitions of dynamic capabilities), and digital heritage (the impact of previous investments/initiatives in information infrastructure that either facilitates or constrains organizational maneuverability in line with definitions of technology debt) | Assessing maturity of service accessibility. Focused on organizational capabilities. |

| (Panayiotou & Stavrou, 2019) | Maturity assessment framework | Information (quality, availability, and management of information), interaction (level and quality of interaction and communication between the local government and citizens), transaction (ability to conduct online transactions and deliver services electronically), integration (integration of web services with backend systems and other government platforms), citizen participation (extent to which citizens are involved in the design and improvement of services). | The framework featured 64 criteria. Assessing maturity of service accessibility. Focused on service delivery. |

| (Kafel et al., 2021) | Multidimensional public sector organizations’ digital maturity model | Digitalization, focused on management, digital competencies of employees, openness of stakeholder’s needs, process digitalization, digital technologies, e-innovativeness. | Assessing maturity at organizational level. Focused on organizational capabilities and service delivery. |

| (Nerima & Ralyté, 2021) | Digital maturity balance model for public organizations | Data, IT governance, strategy, organization, process | Assessing maturity at organizational level. Focused on organizational capabilities and service delivery. |

| (Khademi & Khademi, 2022) | Model for measuring e-government maturity | Web presence, government-citizen interaction, transaction, integration. | Assessing maturity of service accessibility. Focused on service delivery. |

| (Hujran et al., 2023) | SMARTGOV, an Extended Maturity Model | Technology (infrastructure and tools), data (data quality, availability, and usage), process (optimization and automation), organization (culture, capabilities, structure, strategy), service (citizen-centric design and delivery), impact (societal and economic outcomes). | Assessing maturity at organizational level. Focused on organizational capabilities and service delivery. |

| (Patergiannaki & Pollalis, 2023) | e-Government maturity model | Emerging information services, enhanced information services, transactional services, connected services. | Assessing maturity of service accessibility. Focused on organizational capabilities and service delivery. |

| (HosseiniNasab, 2024) | Maturity-driven selection model | Governance structure, strategic alignment, resource management, risk assessment, performance measurement. | Assessing maturity at organizational level. Focused on organizational capabilities and service delivery. |

| (Aristovnik et al., 2024) | Model for measuring the digital state in public administration organizations | Technology, structure, people, organizational culture, processes, external environment, good governance, digitalization. | Assessing maturity at organizational level. Focused on organizational capabilities and service delivery. |

| (Zakiuddin et al., 2024) | Digital service transformation maturity model | Objectives, training, structure, process, policy. | Assessing maturity at organizational level. Focused on organizational capabilities and service delivery. |

Appendix B

| Component | Items | Abbreviation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digital Consistency | Strategy | 1. | Digital governance is implemented gradually according to planned schedules, and during crises, existing resources are utilized to the maximum extent | DConS1 |

| 2. | Digital governance helps prepare for crisis prevention, ensures control, and preserves existing abilities (e.g., operational quality levels) | DConS2 | ||

| 3. | In our organization, digital governance occurs using existing information and communication technology (ICT) tools to ensure business continuity and stability and reduce risks and vulnerabilities | DConS3 | ||

| Employees | 1. | Our employees can use digital tools and official municipal ICT channels | DConE1 | |

| 2. | The stability and support of digital activities are essential for managers who use official municipal ICT channels, tools, and control how employees use them | DConE2 | ||

| 3. | In response to crises, training is provided to update employees’ knowledge and skills on digitalization | DConE3 | ||

| Processes | 1. | Digital governance is developed through precise planning, action design, and employee supervision | DConP1 | |

| 2. | In times of crisis, we use existing ICT channels and tools to ensure the stability and continuity of our operations | DConP2 | ||

| 3. | Using digital tools ensures high-quality process management in times of crisis | DConP3 | ||

| Digital Adaptation | Strategy | 1. | In our organization, digital governance is developed in a constant search for novel resources and opportunities | DAdaS1 |

| 2. | We see crises as an opportunity to start the use of alternative digital tools or channels that support the quality of activities (speed, accessibility, transparency, etc.) | DAdaS2 | ||

| 3. | Our organization emphasizes the need for digital governance and cooperation in developing new digital solutions that respond to new situations and needs | DAdaS3 | ||

| Employees | 1. | Employees have good skills in using digital tools, can quickly adapt to new ICT tools and channels and start other digital tools themselves to achieve operational efficiency | DAdaE1 | |

| 2. | Managers are at the forefront of digital advancement, driving change in digitalization, looking for new opportunities, and allowing employees to use a wide range of ICT channels and tools | DAdaE2 | ||

| 3. | To adapt to the changing environment, we encourage employees to constantly update their digitalization knowledge and skills and develop and implement new ICT systems, channels, and tools necessary for operational efficiency | DAdaE3 | ||

| Processes | 1. | We involve employees in defining the goals and aims of the organization’s digital governance development and discussing the implemented activities | DAdaP1 | |

| 2. | While standard ICT tools and channels dominate our organization, we encourage employee digitalization initiatives that help to adapt to changing conditions and needs in times of crisis | DAdaP2 | ||

| 3. | In times of crisis, we stay optimistic and creative, work in teams, and offer new digital practices, testing them and learning from mistakes | DAdaP3 | ||

| Digital Transformation | Strategy | 1. | One of the most important goals for the development of digital governance in times of crisis is an organization’s ability to focus on digital innovation, anticipation of the future, dynamism, digital change, and progress | DTraS1 |

| 2. | In times of crisis, we seek opportunities to ensure continuity, quality, and digital accessibility by becoming the frontrunners of digital change | DTraS2 | ||

| 3. | Our organization’s digital governance development goals are to introduce new administrative service delivery models based on digital technologies, increase operational efficiency through ICT tools, and respond to the latest digital trends | DTraS3 | ||

| Employees | 1. | DTraE1 Employees make decisions based on their prior digitalization experiences. They trust the team and pool collective knowledge to solve problems using digital tools | DTraE1 | |

| 2. | DTraE2 During the work process, we consider changes in the environment, which we see as an opportunity to grow. We are ready to think and act non-traditionally in the digital space (e.g., using artificial intelligence tools) | DTraE2 | ||

| 3. | DTraE3 Our organization’s managers and ICT specialists work together as partners, discuss, encourage, and support new digitalization initiatives, give employees more freedom to act, and advise employees in good faith on issues that arise | DTraE3 | ||

| Processes | 1. | DTraP1 Our organization constantly discusses digital transformation to be ready to react, act, and make innovative proposals in times of crisis | DTraP1 | |

| 2. | DTraP2 Our organization’s digital governance processes are transforming its structure and culture, changing leadership practices (e.g., guided by ICT tools and channels), and providing flexibility in work forms and places | DTraP2 | ||

| 3. | DTraP3 We focus on the citizen as a customer by updating digital technologies. We provide e-services through the e-government gateway, install user-friendly tools, and adapt digital tools to provide personalized services | DTraP3 | ||

| Group of Items | Number of Items | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|

| Digital Consistency | ||

| Strategy | 3 | 0.935 |

| Employees | 3 | 0.880 |

| Processes | 3 | 0.934 |

| Digital Consistency | 9 | 0.965 |

| Digital Adaptation | ||

| Strategy | 3 | 0.940 |

| Employees | 3 | 0.926 |

| Processes | 3 | 0.948 |

| Digital Adaptation | 9 | 0.975 |

| Digital Transformation | ||

| Strategy | 3 | 0.930 |

| Employees | 3 | 0.929 |

| Processes | 3 | 0.931 |

| Digital Transformation | 9 | 0.968 |

| Digital Governance | 27 | 0.988 |

| Component | Abbreviation | Mean | 95% C.I. | St. Deviation | Skewness | Kurtosis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digital Consistency | Strategy | DConS1 | 7.48 | (7.17, 7.78) | 2.08 | −1.04 | 0.94 |

| DConS2 | 7.64 | (7.35, 7.92) | 1.91 | −1.11 | 1.13 | ||

| DConS3 | 7.58 | (7.30, 7.86) | 1.91 | −1.08 | 0.90 | ||

| Employees | DConE1 | 7.88 | (7.63, 8.13) | 1.69 | −0.84 | 0.64 | |

| DConE2 | 7.63 | (7.30, 7.95) | 2.21 | −1.28 | 1.31 | ||

| DConE3 | 7.17 | (6.83, 7.52) | 2.35 | −1.02 | 0.44 | ||

| Processes | DConP1 | 7.15 | (6.84, 7.46) | 2.12 | −1.06 | 0.51 | |

| DConP2 | 7.75 | (7.46, 8.03) | 1.92 | −1.15 | 1.07 | ||

| DConP3 | 7.58 | (7.29, 7.86) | 1.94 | −1.17 | 1.28 | ||

| Digital Adaptation | Strategy | DAdaS1 | 7.42 | (7.11, 7.74) | 2.13 | −1.20 | 1.46 |

| DAdaS2 | 7.15 | (6.81, 7.48) | 2.26 | −1.04 | 0.69 | ||

| DAdaS3 | 7.35 | (7.01, 7.69) | 2.30 | −1.23 | 1.26 | ||

| Employees | DAdaE1 | 7.07 | (6.79, 7.35) | 1.89 | −0.70 | 0.41 | |

| DAdaE2 | 7.42 | (7.06, 7.78) | 2.44 | −1.27 | 1.03 | ||

| DAdaE3 | 7.38 | (7.05, 7.71) | 2.24 | −1.25 | 1.24 | ||

| Processes | DAdaP1 | 7.02 | (6.70, 7.34) | 2.20 | −0.82 | 0.13 | |

| DAdaP2 | 7.02 | (6.69, 7.34) | 2.23 | −0.91 | 0.38 | ||

| DAdaP3 | 7.44 | (7.12, 7.75) | 2.16 | −0.87 | 0.20 | ||

| Digital Transformation | Strategy | DTraS1 | 7.70 | (7.41, 7.99) | 1.98 | −1.13 | 1.20 |

| DTraS2 | 7.32 | (7.00, 7.64) | 2.17 | −1.16 | 1.26 | ||

| DTraS3 | 7.43 | (7.12, 7.74) | 2.13 | −1.11 | 1.24 | ||

| Employees | DTraE1 | 7.35 | (7.08, 7.62) | 1.83 | −0.91 | 0.87 | |

| DTraE2 | 6.81 | (6.49, 7.13) | 2.17 | −0.88 | 0.44 | ||

| DTraE3 | 7.17 | (6.82, 7.52) | 2.38 | −1.07 | 0.54 | ||

| Processes | DTraP1 | 6.59 | (6.21, 6.96) | 2.54 | −0.79 | −0.04 | |

| DTraP2 | 6.82 | (6.48, 7.15) | 2.30 | −0.88 | 0.23 | ||

| DTraP3 | 7.33 | (6.98, 7.67) | 2.34 | −1.00 | 0.34 | ||

Appendix C

| Fit Index | Description | Acceptable/Good Guidelines | Model 1c (Consistency) | Model 1a (Adaptation) | Model 1t (Transformation) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chi-Square (χ2) Test | Tests difference between observed and model-estimated covariance matrices. | Non-significant χ2 (p > 0.05) indicates acceptable fit, but sensitive to sample size. | χ2(24) = 118.666, p < 0.001 | χ2(24) = 41.776, p = 0.014 | χ2(24) = 60.847, p < 0.001 |

| Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) | Evaluates how well the model approximates the population data. | <0.05 = Close fit; 0.05–0.08 = Reasonable fit; >0.10 = Poor fit. | 0.148 (Poor fit) | 0.064 (Reasonable fit) | 0.093 (Borderline/Poor) |

| Comparative Fit Index (CFI) | Compares model fit to a baseline (independence) model. | ≥0.95 often indicates good fit. | 0.950 (Good) | 0.992 (Excellent) | 0.982 (Excellent) |

| Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI)/Non-Normed Fit Index (NNFI) | Adjusts χ2 for model complexity, comparing target and null models. | ≥0.90 acceptable; ≥0.95 preferred for good fit. | 0.925 (Acceptable) | 0.988 (Excellent) | 0.972 (Excellent) |

| Goodness-of-Fit Index (GFI) and Adjusted GFI (AGFI) | Reflect amount of variance explained by the model; AGFI adjusts for complexity. | Historically ≥ 0.90 acceptable but less used today. | GFI = 0.870, AGFI = 0.757 (Below desired) | GFI = 0.954, AGFI = 0.913 (Good) | GFI = 0.928 (Good), AGFI = 0.865 (Slightly low) |

| Normed Fit Index (NFI) and Incremental Fit Index (IFI) | Compare model to null model; IFI adjusts for sample size. | ≥0.90 acceptable, higher is better. | NFI = 0.939, IFI = 0.951 (Good) | NFI = 0.982, IFI = 0.992 (Excellent) | NFI = 0.970, IFI = 0.982 (Excellent) |

| Overall Interpretation | Summary of fit indices | Poor overall fit (High RMSEA, moderate GFI/AGFI) despite good incremental fit indices | Best overall fit (Reasonable RMSEA, high GFI/AGFI, excellent incremental indices) | Good incremental fit but borderline RMSEA; not as strong as Model 1a but better than Model 1c |

| Model 1c (Consistency) | Model 1a (Adaptation) | Model 1t (Transformation) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression Path | Estimate (S.E.) | Regression Path | Estimate (S.E.) | Regression Path | Estimate (S.E.) |

| DConS1 ← Strategy | 1.000 | DAdaS1 ← Strategy | 1.000 | DTraS1 ← Strategy | 1.000 |

| DConS2 ← Strategy | 0.938 (0.050) *** | DAdaS2 ← Strategy | 1.061 (0.057) *** | DTraS2 ← Strategy | 1.284 (0.076) *** |

| DConS3 ← Strategy | 0.967 (0.048) *** | DAdaS3 ← Strategy | 1.154 (0.052) *** | DTraS3 ← Strategy | 1.229 (0.075) *** |

| DConE1 ← Employees | 1.000 | DAdaE1 ← Employees | 1.000 | DTraE1 ← Employees | 1.000 |

| DConE2 ← Employees | 1.571 (0.123) *** | DAdaE2 ← Employees | 1.614 (0.104) *** | DTraE2 ← Employees | 1.237 (0.068) *** |

| DConE3 ← Employees | 1.691 (0.131) *** | DAdaE3 ← Employees | 1.459 (0.096) *** | DTraE3 ← Employees | 1.385 (0.072) *** |

| DConP1 ← Processes | 1.000 | DAdaP1 ← Processes | 1.000 | DTraP1 ← Processes | 1.000 |

| DConP2 ← Processes | 0.879 (0.040) *** | DAdaP2 ← Processes | 1.044 (0.038) *** | DTraP2 ← Processes | 0.912 (0.036) *** |

| DConP3 ← Processes | 0.848 (0.044) *** | DAdaP3 ← Processes | 0.932 (0.046) *** | DTraP3 ← Processes | 0.820 (0.048) *** |

| *** p < 0.001 (statistically significant at the 0.1% level) | |||||

| Covariance | Model 1c (Consistency) | Model 1a (Adaptation) | Model 1t (Transformation) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strategy ↔ Employees | 2.085 (0.288) *** | 2.669 (0.348) *** | 2.410 (0.313) *** |

| Employees ↔ Processes | 2.429 (0.317) *** | 2.844 (0.366) *** | 3.595 (0.433) *** |

| Strategy ↔ Processes | 3.492 (0.416) *** | 3.729 (0.442) *** | 3.497 (0.445) *** |

| *** p < 0.001 (statistically significant at the 0.1% level) | |||

Appendix D

| Fit Index | Description | Acceptable/Good Guidelines | Model 2c (Consistency) | Model 2a (Adaptation) | Model 2t (Transformation) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chi-Square (χ2) Test | Tests difference between observed and model-estimated covariance matrices. | Non-significant χ2 (p > 0.05) indicates acceptable fit, but sensitive to sample size. | χ2(25) = 131.745, p < 0.001 (Significant) | χ2(25) = 57.644, p < 0.001 (Significant) | χ2(25) = 63.436, p < 0.001 (Significant) |

| Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) | Evaluates how well the model approximates the population data. | <0.05 = Close fit; 0.05–0.08 = Reasonable fit; >0.10 = Poor fit. | 0.154 (Poor fit) | 0.085 (Borderline/Reasonable) | 0.093 (Borderline/Poor) |

| Comparative Fit Index (CFI) | Compares model fit to a baseline (independence) model. | ≥0.95 often indicates good fit. | 0.944 (Borderline) | 0.985 (Excellent) | 0.981 (Excellent) |

| Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI)/Non-Normed Fit Index (NNFI) | Adjusts χ2 for model complexity, comparing target and null models. | ≥0.90 acceptable; ≥0.95 preferred for good fit. | 0.919 (Acceptable) | 0.979 (Excellent) | 0.972 (Excellent) |

| Goodness-of-Fit Index (GFI) and Adjusted GFI (AGFI) | Reflect amount of variance explained by the model; AGFI adjusts for complexity. | Historically ≥ 0.90 acceptable but less used today. | GFI = 0.857, AGFI = 0.743 (Below desired) | GFI = 0.935, AGFI = 0.884 (Acceptable) | GFI = 0.928, AGFI = 0.870 (Borderline) |

| Normed Fit Index (NFI) and Incremental Fit Index (IFI) | Compare model to null model; IFI adjusts for sample size. | ≥0.90 acceptable, higher is better. | NFI = 0.932, IFI = 0.944 (Good) | NFI = 0.975, IFI = 0.986 (Excellent) | NFI = 0.969, IFI = 0.981 (Excellent) |

| Overall Interpretation | Summary of fit indices | Poor overall fit High RMSEA, GFI/AGFI below 0.90; incremental indices borderline. | Best overall fit RMSEA borderline but acceptable; excellent incremental indices. | Good incremental fit RMSEA borderline, not as strong as 2a but better than 2c. |

| Regression Path | Estimate (S.E.) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 2c (Consistency) | Model 2a (Adaptation) | Model 2t (Transformation) | |

| Employees ← Strategy | 0.637 (0.054) *** | 0.748 (0.057) *** | 0.924 (0.069) *** |

| Processes ← Employees | 1.549 (0.118) *** | 1.341 (0.097) *** | 1.421 (0.082) *** |

| *** p < 0.001 (statistically significant at the 0.1% level) | |||

Appendix E

| Fit Index | Description | Acceptable/Good Guidelines | Model 3 | Model 3m |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chi-Square (χ2) Test | Tests difference between observed and model-estimated covariance matrices. | Non-significant χ2 (p > 0.05) indicates acceptable fit, but sensitive to sample size. | χ2(312) = 1023.871, p < 0.001 (Significant) | χ2(309) = 945.325, p < 0.001 (Significant) |

| Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) | Evaluates how well the model approximates the population data. | <0.05 = Close; 0.05–0.08 = Reasonable; >0.10 = Poor | 0.113 (Poor) | 0.107 (Poor, slight improvement) |

| Comparative Fit Index (CFI) | Compares model fit to a baseline (independence) model. | ≥0.95 = Good fit | 0.904 (Borderline) | 0.914 (Closer, but still <0.95) |

| Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI)/Non-Normed Fit Index (NNFI) | Adjusts χ2 for complexity; compares target and null models. | ≥0.90 acceptable; ≥0.95 good | 0.892 (Below acceptable) | 0.902 (Just reached acceptable level) |

| Goodness-of-Fit Index (GFI) and Adjusted GFI (AGFI) | Reflects variance explained; AGFI adjusts for complexity. | Historically ≥0.90 acceptable | GFI = 0.696, AGFI = 0.632 (Low) | GFI = 0.718, AGFI = 0.656 (Low) |

| Normed Fit Index (NFI) and Incremental Fit Index (IFI) | Compare model to null; IFI adjusts for sample size. | ≥0.90 acceptable, higher is better | NFI = 0.868, IFI = 0.904 (NFI < 0.90; IFI borderline) | NFI = 0.878, IFI = 0.915 (NFI < 0.90; IFI borderline) |

| Overall Interpretation | Summary of fit indices | Poor-to-borderline fit (RMSEA high, low GFI/AGFI) | Poor-to-borderline fit (Further slight improvements in TLI/CFI, RMSEA still poor) |

| Regression Path | Estimate (S.E.) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Digital governance maturity level → | Consistency | Adaptation | Transformation |

| Employees ← Strategy | 0.653 (0.054) *** | 0.596 (0.070) *** | 0.481 (0.101) *** |

| Processes ← Employees | 1.610 (0.120) *** | 0.929 (0.110) *** | 0.699 (0.130) *** |

| Dimension → | Strategy | Employee | Processes |

| Adaptation ← Consistency | 0.970 (0.060) *** | 0.226 (0.092) ** | 0.330 (0.070) *** |

| Transformation ← Adaptation | 0.794 (0.054) *** | 0.534 (0.110) *** | 0.587 (0.101) *** |

| *** p < 0.001 (statistically significant at the 0.1% level), i.e. ** p < 0.05 (statistically significant at the 5% level) | |||

| Regression Path | Estimate (S.E.) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Digital governance maturity level→ | Consistency | Adaptation | Transformation |

| Strategy ← Employees | 1.333 (0.122) *** | 1.007 (0.100) *** | 0.298 (0.088) *** |

| Processes ← Employees | 0.962 (0.129) *** | 0.748 (0.180) *** | 0.495 (0.149) *** |

| Processes ← Strategy | 0.457 (0.075) *** | 0.279 (0.141) ** | 0.202 (0.164) |

| Dimension→ | Strategy | Employee | Processes |

| Adaptation ← Consistency | 0.237 (0.062) *** | 1.146 (0.111) *** | 0.191 (0.083) ** |

| Transformation ← Adaptation | 0.561 (0.079) *** | 1.017 (0.079) *** | 0.593 (0.125) *** |

| *** p < 0.001 (statistically significant at the 0.1% level), i.e. ** p < 0.05 (statistically significant at the 5% level) | |||

References

- Adade, D., & de Vries, W. T. (2025). An extended TOE framework for local government technology adoption for citizen participation: Insights for city digital twins for collaborative planning. Transforming Government: People, Process and Policy, 19(1), 53–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnan, H. R., Hidayanto, A. N., & Kurnia, S. (2021). Citizens’ or government’s will? Exploration of why Indonesia’s local governments adopt technologies for open government. Sustainability, 13(20), 11197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahsan, M. J., & Tahir, M. Z. (2025). Building resilience at work: The role of employee development practices, employee competence and employee mindfulness. Available online: https://www.emerald.com/mbe/article-abstract/doi/10.1108/MBE-09-2024-0140/1254848/Building-resilience-at-work-the-role-of-employee?redirectedFrom=fulltext (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Ansell, C., & Torfing, J. (2025). Robust governance of crisis-induced turbulence: An analytical framework. In C. Ansell, E. Sørensen, J. Torfing, & J. Trondal (Eds.), Robust public governance in a turbulent era (pp. 57–75). Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Aras, A., & Büyüközkan, G. (2023). Digital transformation journey guidance: A holistic digital maturity model based on a systematic literature review. Systems, 11(4), 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aristovnik, A., Ravšelj, D., & Murko, E. (2024). Decoding the digital landscape: An empirically validated model for assessing digitalisation across public administration levels. Administrative Sciences, 14(3), 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcevičius, E., Cibaitė, G., Codagnone, C., Gineikytė, V., Klimavičiūtė, V., Liva, G., Matulevič, L., Misuraca, G., & Vanini, I. (2019). Exploring digital government transformation in the EU: Analysis of the state of the art and review of literature (EUR 29987 EN). Publications Office of the European Union.

- Bell, S. (2019). Organisational resilience: A matter of organisational life and death. Continuity & Resilience Review, 1(1), 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhard, I., Norström, L., Snis, U. L., Gråsjö, U., & Gellerstedt, M. (2018). Degree of digitalization and citizen satisfaction: A study of the role of local e-government in Sweden. Electronic Journal of e-Government, 16(1), 59–71. Available online: https://academic-publishing.org/index.php/ejeg/article/view/651/614 (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Bhatia, V., & Bhatia, S. (2025). Evaluating e-governance: A comparative analysis and way forward. Digital Policy, Regulation and Governance, 27(6), 724–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boin, A., Hart, P., Stern, E., & Sundelius, B. (2005). The politics of crisis management: Public leadership under pressure. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T. A. (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson, F., Matteby, M., & Magnusson, J. (2023). Digital transformation drift: A population study of Swedish municipalities. In D. D. Cid, & N. Sabatini (Eds.), Proceedings of the 24th annual international conference on digital government research (pp. 318–326). Association for Computing Machinery. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, N. (2021). Analyzing local government capacity and performance: Implications for sustainable development. Sustainability, 13(7), 3862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clement, J., Esposito, G., & Crutzen, N. (2023). Municipal pathways in response to COVID-19: A strategic management perspective on local public administration resilience. Administration & Society, 55(1), 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, A., Yigitcanlar, T., Li, R. Y. M., Corchado, J. M., Cheong, P. H., Mossberger, K., & Mehmood, R. (2023). Understanding local government digital technology adoption strategies: A PRISMA review. Sustainability, 15(12), 9645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, R. S., & Stazyk, E. C. (2017). Putting the methodological cart before the theoretical horse? Examining the application of SEM to connect theory and method in public administration research. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 37(2), 202–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debeljak, A., & Dečman, M. (2022). Digital transformation of Slovenian urban municipalities: A quantitative report on the impact of municipality population size on digital maturity. The NISPAcee Journal of Public Administration and Policy, 15(2), 25–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Carvalho, J., & Chima, F. O. (2014). Applications of structural equation modeling in social sciences research. American International Journal of Contemporary Research, 4(1), 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- De la Boutetière, H., Montagner, A., & Reich, A. (2018). Unlocking success in digital transformations. McKinsey and Company. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/McKinsey/Business%20Functions/Organization/Our%20Insights/Unlocking%20success%20in%20digital%20transformations/Unlocking-success-in-digital-transformations.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Dvorak, J., Burkšienė, V., Dūda, M., Obrikienė, A., & Narbutienė, I. (2020). E. dalyvavimas: Galimybės ir iššūkiai savivaldai. Klaipėdos Universitetas. [Google Scholar]

- Eggers, W. D., & Bellman, J. (2015). Digital government transformation: The journey to government’s digital future. Deloitte University Press. Available online: https://www.deloitte.com/content/dam/assets-shared/legacy/docs/perspectives/2022/gx-global-findings-digital-government-transformation.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Eom, S. J., & Lee, J. (2022). Digital government transformation in turbulent times: Responses, challenges, and future direction. Government Information Quarterly, 39(2), 101690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkut, B. (2020). From digital government to digital governance: Are we there yet? Sustainability, 12(3), 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, G., Terlizzi, A., Guarino, M., & Crutzen, N. (2024). Interpreting digital governance at the municipal level: Evidence from smart city projects in Belgium. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 90(2), 301–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fägerlind, I., & Saha, L. J. (2016). Education and national development: A comparative perspective (2nd ed.). Pergamon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fekete, A., Hetkämper, C., & Bauer, C. (2025). Resilience in the context of civil protection and municipalities. In E. Marks, C. Heinzelmann, & G. R. Wollinger (Eds.), International perspectives of crime prevention 13: Contributions from the 28th German prevention congress (pp. 95–113). Forum Verlag Godesberg. [Google Scholar]

- Gangneux, J., & Joss, S. (2022). Crisis as driver of digital transformation? Scottish local governments’ response to COVID-19. Data & Policy, 4, e26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Garcia, J. R., Dawes, S. S., & Pardo, T. A. (2018). Digital government and public management research: Finding the crossroads. Public Management Review, 20(5), 633–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigalashvili, V. (2023). Digital government and digital governance: Grand concept. International Journal of Scientific and Management Research, 6(02), 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartanto, D., Dalle, J., Akrim, A., & Anisah, H. U. (2021). Perceived effectiveness of e-governance as an underlying mechanism between good governance and public trust: A case of Indonesia. Digital Policy, Regulation and Governance, 23(6), 598–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haryanti, T., Rakhmawati, N. A., & Subriadi, A. P. (2023). The extended digital maturity model. Big Data and Cognitive Computing, 7(1), 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z., Huang, H., Choi, H., & Bilgihan, A. (2023). Building organizational resilience with digital transformation. Journal of Service Management, 34(1), 147–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, T., & Solarte-Vasquez, M. C. (2022). The Estonian e-residency programme and its role beyond the country’s digital public sector ecosystem. Revista CES Derecho, 13(2), 184–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horák, P., & Špaček, D. (2024). Organizational resilience of public sector organizations responding to the COVID-19 pandemic in Czechia and key influencing factors: Use of the Nograšek and Vintar model. International Journal of Public Administration, 48, 485–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HosseiniNasab, S. M. (2024). A maturity-driven selection model for effective digital transformation governance mechanisms in large organizations. Kybernetes, 54(9), 5106–5132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hujran, O., Alarabiat, A., Al-Adwan, A. S., & Al-Debei, M. (2023). Digitally transforming electronic governments into smart governments: SMARTGOV, an extended maturity model. Information Development, 39(4), 811–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idzi, F. M., & Gomes, R. C. (2022). Digital governance: Government strategies that impact public services. Global Public Policy and Governance, 2(4), 427–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jans, W., Denters, B., Need, A., & Van Gerven, M. (2016). Mandatory innovation in a decentralised system: The adoption of an e-government innovation in Dutch municipalities. Acta Politica, 51, 36–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, P. R., & Islam, S. (2018). E-government maturity model for sustainable e-government services from the perspective of developing countries. Sustainability, 10(6), 1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafel, T., Wodecka-Hyjek, A., & Kusa, R. (2021). Multidimensional public sector organizations’ digital maturity model. Administration & Public Management Review, 37, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaszás, N., Ernszt, I., & Jakab, B. (2023). The emergence of organizational and human factors in digital maturity models. Management: Journal of Contemporary Management Issues, 28(1), 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khademi, S. M., & Khademi, S. R. (2022). Designing a model for measuring e-government maturity (case study: Lorestan governor department). Public Organizations Management, 10(2), 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshroo, M., & Talari, M. (2023). Scientific mapping of digital transformation strategy research studies in the Industry 4.0: A bibliometric analysis. Nankai Business Review International, 14(1), 3–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitsios, F., Kamariotou, M., & Mavromatis, A. (2023). Drivers and outcomes of digital transformation: The case of public sector services. Information, 14(1), 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsogeorgopoulou, V. (2023). Unleashing the productive potential of digitalisation in Lithuania (OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1753). OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, S., Jones, P., Kailer, N., Weinmann, A., Chaparro-Banegas, N., & Roig-Tierno, N. (2021). Digital transformation: An overview of the current state of the art of research. Sage Open, 11(3), 21582440211047576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusto, B., & Klepacki, B. (2022). E-services in municipal offices during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Modern Science, 2(49), 621–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee-Geiller, S., & Lee, T. (2022). How does digital governance contribute to effective crisis management? A case study of Korea’s response to COVID-19. Public Performance & Management Review, 45(4), 860–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekkas, C., & Souitaris, V. (2023). Bureaucracy meets digital reality: The unfolding of urban platforms in European municipal governments. Organization Studies, 44(10), 1649–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lithuania Co-create. (2024). Lithuania ranked among the world’s leaders in e-government development. Lithuania Co-create. Governance. Available online: https://lithuania.lt/governance-in-lithuania/lithuania-ranked-among-the-worlds-leaders-in-e-government-development/ (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Lnenicka, M., Luterek, M., & Majo, L. T. (2024). Analysis of e-government and digital society indicators over the years: A comparative study of the EU member states. Digital Policy, Regulation and Governance, 26(5), 560–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnusson, J., & Nilsson, A. (2019). Digital maturity in the public sector: Design and evaluation of a new model. Swedish Center for Digital Innovation, University of Gothenburg. Available online: https://gup.ub.gu.se/file/208009 (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Manoharan, A. P., Melitski, J., & Holzer, M. (2023). Digital governance: An assessment of performance and best practices. Public Organization Review, 23(1), 265–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manyena, S. B., O’Brien, G., O’Keefe, P., & Rose, J. (2011). Disaster resilience: A bounce back or bounce forward ability? Local Environment, 16(5), 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mergel, I. (2016). Social media institutionalization in the U.S. federal government. Government Information Quarterly, 33(1), 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mettler, T., & Ballester, O. (2021, December 12–15). Maturity models in information systems: A review and extension of existing guidelines. Forty-Second International Conference on Information Systems (pp. 1–16), Austin, TX, USA. Available online: https://serval.unil.ch/resource/serval:BIB_F7DAC07C42DC.P001/REF (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Meyerhoff Nielsen, M. (2017). Governance failure in light of Government 3.0: Foundations for building next generation eGovernment maturity models. In A. Ojo, & J. Millard (Eds.), Government 3.0–next generation government technology infrastructure and services: Roadmaps, enabling technologies & challenges (pp. 63–109). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millard, J. (2023). Impact of digital transformation on public governance. Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Näswall, K., Malinen, S., Kuntz, J., & Hodliffe, M. (2019). Employee resilience: Development and validation of a measure. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 34(5), 353–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nerima, M., & Ralyté, J. (2021). Towards a digital maturity balance model for public organizations. In S. Cherfi, A. Perini, & S. Nurcan (Eds.), International conference on research challenges in information science (pp. 295–310). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, J. A., Elmholdt, K. T., & Noesgaard, M. S. (2024). Leading digital transformation: A narrative perspective. Public Administration Review, 84(4), 589–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkomo, L., & Kalisz, D. (2023). Establishing organisational resilience through developing a strategic framework for digital transformation. Digital Transformation and Society, 2(4), 403–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolte, I. M., & Lindenmeier, J. (2024). Creeping crises and public administration: A time for adaptive governance strategies and cross-sectoral collaboration? Public Management Review, 26(11), 3104–3125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2024). 2023 OECD digital government index: Results and key findings (OECD Public Governance Policy Papers, No. 44). OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panayiotou, N., & Stavrou, V. (2019). A proposed maturity assessment framework of the Greek local government Web Electronic Services. Transforming Government: People, Process and Policy, 13(3/4), 237–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M. J., & Choi, H. (2023). Bending, not breaking: Digital resilience as a pathway to organizational renewal. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/Delivery.cfm/87dcf8be-2573-4a74-8e72-1d82fb330871-MECA.pdf?abstractid=5223504&mirid=1 (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Patergiannaki, Z., & Pollalis, Y. (2023). E-government maturity assessment: Evidence from Greek municipalities. Policy & Internet, 15(1), 6–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittaway, J. J., & Montazemi, A. R. (2020). Know-how to lead digital transformation: The case of local governments. Government Information Quarterly, 37(4), 101474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plimakis, I. (2023). Organizational change in times of crisis: COVID-19 pandemic and strategy change in municipal government. In D. Belias, I. Rossidis, C. Papademetriou, A. Masouras, & S. Anastasiadou (Eds.), Managing successful and ethical organizational change (pp. 217–240). IGI Global Scientific Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Rybnikova, I., Juknevičienė, V., Toleikienė, R., Leach, N., Abolina, I., Reinholde, I., & Sillamae, J. (2022). Digitalisation and e-leadership in local government before COVID-19: Results of an exploratory study. Forum Scientiae Oeconomia, 10(2), 174–190. Available online: http://ojs.wsb.edu.pl/index.php/fso/article/view/532/315 (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Scupola, A., & Mergel, I. (2021, July 30). Value co-creation and digital service transformation: The case of Denmark. SSRN. Available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5223504 (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Sigurjonsson, T. O., Jónsson, E., & Gudmundsdottir, S. (2024). Sustainability of digital initiatives in public services in digital transformation of local government: Insights and implications. Sustainability, 16(24), 10827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spicer, Z., Lyons, J., & Calvert, M. (2023). Preparedness and crisis-driven policy change: COVID-19, digital readiness, and information technology professionals in Canadian local government. Canadian Public Administration, 66(2), 176–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprengel, A., & Sven, U. P. (2024). Challenges and approaches in developing multidimensional maturity models in the context of digital transformation. PACIS 2024 Proceedings, 2, 1–9. Available online: https://aisel.aisnet.org/pacis2024/track15_govce/track15_govce/2 (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Statistics Solutions. (2025a). Confirmatory factor analysis. Available online: https://www.statisticssolutions.com/academic-solutions/resources/directory-of-statistical-analyses/confirmatory-factor-analysis/ (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Statistics Solutions. (2025b). Structural equation modeling. Available online: https://www.statisticssolutions.com/free-resources/directory-of-statistical-analyses/structural-equation-modeling/ (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Susilowati, Y. T., Nurcahyanti, A., & Sugiyarti, G. (2025). Digital transformation maturity and digital change management effects on work-life integration through digital work adaptation of Semarang City government ASN. Saudi Journal of Business and Management Studies, 10(1), 10–21. Available online: https://saudijournals.com/media/articles/SJBMS_101_10-21.pdf (accessed on 9 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Taleb, N. N. (2012). Antifragile: Things that gain from disorder. Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Tangi, L., Gaeta, M., Benedetti, M., Gastaldi, L., & Noci, G. (2022). Assessing the effect of organisational factors and ICT expenditures on e-maturity: Empirical results in Italian municipalities. Local Government Studies, 49(6), 1333–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangi, L., Janssen, M., Benedetti, M., & Noci, G. (2021). Digital government transformation: A structural equation modelling analysis of driving and impeding factors. International Journal of Information Management, 60, 102356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teichert, R. (2019). Digital transformation maturity: A systematic review of literature. Acta Universitatis Agriculturae et Silviculturae Mendelianae Brunensis, 67(6), 1673–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thordsen, T., & Bick, M. (2023). A decade of digital maturity models: Much ado about nothing? Information Systems and e-Business Management, 21(4), 947–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tubis, A. A. (2023). Digital maturity assessment model for the organizational and process dimensions. Sustainability, 15(20), 15122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vial, G. (2021). Understanding digital transformation: A review and a research agenda. In A. Hinterhuber, T. Vescovi, & F. Checchinato (Eds.), Managing digital transformation. Understanding the strategic process (pp. 13–66). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viana, A. C. A. (2021). Digital transformation in public administration: From e-government to digital government. International Journal of Digital Law, 1, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigoda-Gadot, E., & Mizrahi, S. (2024). The digital governance puzzle: Towards integrative theory of humans, machines, and organizations in public management. Technology in Society, 77, 102530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitálišová, K., Sýkorová, K., Koróny, S., Laco, P., Vaňová, A., & Borseková, K. (2023). Digital transformation in local municipalities: Theory versus practice. In G. Rouet, & T. Côme (Eds.), Participatory and digital democracy at the local level: European discourses and practices (pp. 207–226). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Vrbek, S., & Jukić, T. (2025). Navigating the aftermath: Evaluating COVID-19’s lasting effects–multiple case studies from Slovenian public administration. Available online: https://www.emerald.com/ijpsm/article/doi/10.1108/IJPSM-05-2024-0136/1250442/Navigating-the-aftermath-evaluating-COVID-19-s (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Waara, Å. (2025). Examining digital government maturity models: Evaluating the inclusion of citizens. Administrative Sciences, 15(3), 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X., Ramesh, M., & Howlett, M. (2017). Policy capacity: Conceptual framework and essential components. In X. Wu, M. Howlett, & M. Ramesh (Eds.), Policy capacity and governance: Assessing governmental competences and capabilities in theory and practice (pp. 1–25). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X., & Dai, M. (2024). Evaluation of local government digital governance ability and sustainable development: A case study of Hunan province. Sustainability, 16(14), 6084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, C. M., & Luthans, F. (2007). Positive organizational behavior in the workplace: The impact of hope, optimism, and resilience. Journal of Management, 33(5), 774–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, R., Chen, Y., Jin, Y., & Zhang, S. (2024). Evaluating the impact of digital transformation on urban innovation resilience. Systems, 13(1), 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakiuddin, N. F., Anggara, S. M., & Suhardi. (2024). Developing digital service transformation maturity model in public sector. IEEE Access, 12, 174491–174506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y., Wan, H., Carlos, L. A., Ye, J., & Zeng, S. (2025). Evaluating digital maturity in specialized enterprises: A multi-criteria decision-making approach. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 21(1), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Toleikienė, R.; Butkus, M.; Bartuševičienė, I.; Juknevičienė, V. Assessing Digital Governance Maturity in the Context of Municipal Resilience: The Triadic Model, Its Dimensions and Interrelations. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 435. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15110435

Toleikienė R, Butkus M, Bartuševičienė I, Juknevičienė V. Assessing Digital Governance Maturity in the Context of Municipal Resilience: The Triadic Model, Its Dimensions and Interrelations. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(11):435. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15110435

Chicago/Turabian StyleToleikienė, Rita, Mindaugas Butkus, Ilona Bartuševičienė, and Vita Juknevičienė. 2025. "Assessing Digital Governance Maturity in the Context of Municipal Resilience: The Triadic Model, Its Dimensions and Interrelations" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 11: 435. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15110435

APA StyleToleikienė, R., Butkus, M., Bartuševičienė, I., & Juknevičienė, V. (2025). Assessing Digital Governance Maturity in the Context of Municipal Resilience: The Triadic Model, Its Dimensions and Interrelations. Administrative Sciences, 15(11), 435. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15110435