1. Introduction

In recent decades, the pursuit of organizational success has driven isolated research into increasingly intangible assets, such as psychological safety (PS), knowledge management (KM), and organizational learning (OL). These constructs have garnered attention not only as individual pillars of organizational development but also as interconnected drivers of innovation, inclusion, and continuous improvement (

Al Hawamdeh & Al-Edenat, 2025;

A. C. Edmondson & Lei, 2014;

Imran et al., 2025;

Newman et al., 2017).

In this sense, organizational success can be indirectly understood through outcomes such as enhanced innovation capacity, strengthened inclusion, and sustained continuous improvement, which are consistently linked in the literature to PS, KM, and OL.

PS has gained significant traction in organizational research, particularly in relation to knowledge-intensive processes. PS refers to a shared belief among team members that the environment is safe for interpersonal risk-taking, allowing individuals to express themselves without fear of negative consequences to self-image, status, or career (

A. Edmondson, 1999). This construct is foundational for fostering open communication, learning behaviors, and innovation, all of which are essential for effective KM in contemporary organizations (

A. C. Edmondson & Lei, 2014).

Recent empirical work has expanded upon our understanding of PS in modern organizations, linking it to inclusive leadership and team innovation (

Li & Tang, 2022), error tolerance in knowledge environment and knowledge hiding (

Kucharska, 2021), and the synergy of culture and knowledge sharing—both tacit and explicit—as vital to developing dynamic capabilities (

Kucharska & Rebelo, 2022). Furthermore, studies have explored how leadership styles influence voice behaviour via PS (

Fatoki, 2024), and how PS mediates the relationship between inclusive leadership and helping behavior (

Qasim et al., 2022).

KM encompasses strategies and practices aimed at identifying, creating, sharing, and applying knowledge to achieve organizational objectives. These processes are inherently social and depend on individuals’ willingness to share what they know, ask questions, and learn from one another. PS plays a critical role in enabling these behaviors by reducing fear-based silence and promoting a culture of openness and trust (

Newman et al., 2017). In psychologically safe environments, employees are more likely to engage in knowledge-sharing behaviors, contribute to collective problem-solving, and participate in reflective learning processes.

OL is a fundamental concept in the contemporary business environment, driven by a scenario of constant change and complexity (

Shet, 2024). It is understood as a continuous social process where individuals participate in situated practices that reproduce and expand organizational knowledge structures, linking multiple levels of learning, including individual, group and organizational (

Crossan et al., 1999;

Evenseth et al., 2022). A significant link exists between knowledge creation and OL, as the generation of new ideas and practices fuels the development of shared understandings and organizational routines. Through this process, knowledge creation acts as a catalyst that transforms individual insights into collective learning outcomes, reinforcing the dynamic cycle between innovation and adaptation (

Nonaka & von Krogh, 2009).

Despite growing interest in these domains, the literature remains fragmented regarding how these concepts intersect and reinforce each other within learning-oriented organizational cultures. Understanding these relationships is vital for designing environments that foster trust, promote collaboration, and sustain long-term learning.

This study is positioned within the broader challenge of building sustainable learning cultures, in which PS provides the trust foundation, KM enables effective knowledge flows, and OL ensures adaptive and resilient practices. In this sense, resilience is not treated as an isolated construct but rather as an emergent property of learning-oriented cultures—one that results from the continuous interaction between psychological safety, knowledge sharing, and collective learning. To address this challenge, the research examines the conceptual and empirical relationships among PS, KM, and OL in academic publications from 2000 to 2025. Based on these considerations, this study is guided by the following central research question: In what ways do PS, KM, and OL interrelate to foster organizational learning cultures?

To address this question, we perform a bibliometric and thematic analysis using the SPIDER framework, PRISMA methodology, and VOSviewer software (version 1.6.20). Our findings contribute to a deeper understanding of how these constructs converge to shape inclusive and learning-oriented environments, culminating in a conceptual model that bridges theory and practice. In addition to descriptive bibliometric mapping, the study also integrates thematic synthesis and inductive model-building, thus adopting a hybrid approach that combines bibliometric analysis with qualitative content review.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Psychological Safety

PS is defined as the shared belief that a team is safe for interpersonal risk-taking (

A. C. Edmondson, 2019;

Forte et al., 2024;

Newman et al., 2017). In a psychologically safe environment, employees feel comfortable expressing themselves and being themselves, without fear of embarrassment, ridicule or retaliation (

Bülbül et al., 2022;

A. C. Edmondson, 2019). This means that they will not be rejected for what they think and say, and that their knowledge, skills, and abilities will be respected.

PS acts as a socio-emotional resource that allows people to minimize feelings of threat and perceived fear of expressing innovative ideas or behaving collaboratively (

Bülbül et al., 2022). It is a condition in which individuals feel (1) included, (2) safe to learn, (3) safe to contribute, and (4) safe to challenge the status quo, all without fear of being shamed, marginalized, or punished in any way (

Clark, 2020;

S. Kim et al., 2020).

Thus, PS is a fundamental concept that refers to the shared belief among team members that the work environment is conducive to interpersonal risk-taking without fear of negative consequences (

Rodrigues & Figueiredo, 2025). This proactive and positive climate allows individuals to openly express their thoughts and ideas, ask questions without feeling ashamed or incompetent, admit mistakes without fear of punishment or humiliation, and provide constructive feedback with respect. It is distinct from the mere absence of fear or conflict, and is not just individual trust, but a collective perception of a normative environment that values respect for individual competence, even in the face of divergent opinions (

Rodrigues & Figueiredo, 2025).

2.2. Knowledge Management

Knowledge is acquired through experiences and tacit and explicit learning associated with specific individuals. In the organizational context, knowledge sharing processes act as mediators in the effect of trust, collaboration, and learning on the effectiveness of knowledge management (

Moon & Lee, 2014).

KM is a crucial field that has explained how information is produced, developed, maintained, and used within organizations or nations, promoting learning from the past and innovation (

Taherdoost & Madanchian, 2023). It is recognized as a fundamental organizational capability for leveraging competitive advantage. The main objective of KM is to develop techniques that facilitate the sharing of the right knowledge with the right people at the right time (

Al Hawamdeh & Al-Edenat, 2025). In addition, KM involves identifying, managing and leveraging individual and collective knowledge to help a company become more competitive (

L.-S. Huang et al., 2011). Fundamentally, it is about capitalizing on organizational intellect and experience to drive innovation, with knowledge being considered a valuable asset that can be found in organizational culture, routines, policies, systems, documents or in the employees themselves (

Sousa & Moço, 2015).

KM is the process of generating, acquiring, capturing, sharing, and using knowledge within an organization to improve its learning capacity and performance (

Al Hawamdeh & Al-Edenat, 2025). Sources consistently identify key processes, such as knowledge creation, knowledge sharing, and knowledge application, as widely recognized as fundamental to a knowledge-driven organization. A key dimension of KM involves the dynamic interaction between tacit and explicit knowledge. Tacit knowledge refers to skills, experiences, and expertise embedded in individuals, whereas explicit knowledge is codified and formalized through documents, databases, or procedures. The conversion between these two forms, as outlined in Nonaka and Takeuchi’s SECI model (1995), enables organizations to transform individual expertise into collective resources that can be shared, adapted, and applied. Recent empirical studies emphasize that balancing tacit and explicit knowledge flows is essential: for example

Kucharska (

2021) shows how mistake acceptance in learning cultures supports tacit knowledge sharing and mitigates knowledge hiding;

Duan et al. (

2022) investigate explicit vs. tacit knowledge hiding and their differential impacts;

Natek and Lesjak (

2021) explore how knowledge management systems support explicit codification and tacit-knowledge support;

Idrees et al. (

2023) highlight KM’s role in new product development requiring both forms of knowledge.

Regardless of categorization, KM also encompasses the infrastructure, capabilities and management activities that facilitate and enhance these knowledge processes (

Obeng et al., 2024), with knowledge transfer being highlighted as a mechanism for harmonizing information Exchange (

Nasrallah et al., 2025).

In terms of organizational benefits and prospects, companies strive to convert personal knowledge (consisting of information, experience and understanding) into organizational knowledge performance (

Al Hawamdeh & Al-Edenat, 2025). KM is seen as a strategic asset that enables value creation (

Latif et al., 2020), and is vital for sustained success. Effective KM can lead to superior results through the efficient management of knowledge resources. (

Hussain & Li, 2022).

2.3. Organizational Learning

OL is a crucial way of achieving a company’s strategic renewal, revealing an inherent tension between assimilating new knowledge (exploration) and using what has already been learned (exploitation) (

Crossan et al., 1999). This dynamic process is articulated through four interconnected sub-processes: intuition, interpretation, integration and institutionalization (the 4I’s) (

Crossan et al., 1999). A vital component of OL is the ability to unlearn, which acts as a “cycle of metamorphosis” by removing obstacles created by misleading knowledge and obsolete routines, paving the way for new learning (

Evenseth et al., 2022). Distinct from KM, which focuses primarily on cognition, OL establishes a direct link between cognition and action (

Crossan et al., 1999).

The relevance of OL to this study is accentuated by its intrinsic relationship with resilience and organizational effectiveness. OL is an inherent and essential element of organizational resilience (OR) (

Evenseth et al., 2022), being both a precondition and an outcome of OR, in a mutually reinforcing cycle. By enabling the extraction of positive lessons from adverse experiences and promoting adaptability and resilience, OL enables organizations to thrive in Volatility, Uncertainty, Complexity and Ambiguity (VUCA) environments (

Shet, 2024). Promoting PS in the workplace amplifies this learning capacity, as organizations become more capable of embracing learning and continuous improvement (

Rodrigues & Figueiredo, 2025), facilitating knowledge sharing and learning from mistakes. In this way, OL not only boosts organizational performance and innovation (

Shet, 2024;

Rodrigues & Figueiredo, 2025), but also contributes to the continuous development of employees, making them more relevant and competitive in a constantly evolving job market (

Shet, 2024).

2.4. Psychological Safety and Knowledge Management in Organizational Contexts

Empirical studies have consistently demonstrated the positive relationship between PS and knowledge-related outcomes.

Carmeli and Gittell (

2008) found that high-quality relationships characterized by shared goals, mutual respect, and relational coordination foster PS, which in turn facilitates learning from failures—a key mechanism through which organizations accumulate and refine knowledge.

Siemsen et al. (

2009) showed that PS significantly influences employees’ willingness to share knowledge, particularly when they feel confident in the value of their contributions. These findings suggest that PS not only encourages knowledge sharing but also interacts with individual-level factors such as self-efficacy and perceived expertise.

The mechanisms through which PS enhances KM are multifaceted. First, it reduces the perceived interpersonal risk associated with admitting ignorance or making mistakes, which are often necessary precursors to learning and knowledge exchange. Second, it supports the development of trust and mutual respect, which are essential for the free flow of information across hierarchical and functional boundaries. Third, PS enables teams to engage in constructive conflict and dialogue, which are critical for integrating diverse perspectives and generating new knowledge (

A. C. Edmondson & Lei, 2014). PS has also been shown to mediate the relationship between leadership behaviors and team learning. Leaders who model openness, encourage voice, and respond supportively to failure create conditions that promote PS, which in turn enhances team learning behaviors and knowledge integration (

A. C. Edmondson, 2019).

A systematic review by

Newman et al. (

2017) further reinforces the centrality of PS in KM. Their analysis of empirical studies revealed that PS is a consistent predictor of collaborative behaviors, knowledge sharing, and OL. They argued that PS should be considered a foundational condition for any KM initiative, as it directly influences the willingness of individuals to engage in the social processes that underpin knowledge creation and dissemination.

Recent empirical evidence demonstrates a strong connection between PS and KM practices across diverse organizational contexts. The literature consistently shows that PS serves as a positive antecedent to knowledge-sharing behaviors and team performance (

Rivera et al., 2020;

Siemsen et al., 2009).

van der Berg (

2020) provided quantitative evidence of this relationship, reporting a strong positive correlation between PS and knowledge sharing (r = 0.72,

p < 0.001). In healthcare settings,

Kessel et al. (

2012) found that PS predicts creative team performance through knowledge sharing, while

Mancini and Ribiere (

2018) demonstrated similar effects in pharmaceutical enterprises.

C.-C. Huang and Jiang (

2012) observed that PS influences team performance via enhanced knowledge-sharing practices, especially in environments where innovation and collaboration are critical.

Rivera et al. (

2020) noted that PS is a fundamental antecedent to knowledge sharing when supported by organizational cultures emphasizing respect and trust.

The relationship between PS and KM involves mediating and moderating factors. Leadership emerges as a crucial element: PS mediates the effect of intellectual stimulation on knowledge sharing (

Yin et al., 2019), while abusive supervision can diminish PS and consequently reduce knowledge-sharing behaviors (

Agarwal & Anantatmula, 2021). Individual and team-level factors also play important roles.

Siemsen et al. (

2009) found that confidence in knowledge moderates the effect of PS, while

C.-C. Huang and Jiang (

2012) demonstrated that team learning mediates the relationship between PS and team performance. Psychological capital has been identified as both a moderator and mediator in the relationship between supervisory behaviors and knowledge-sharing outcomes (

Agarwal & Anantatmula, 2022).

Cultural and organizational contexts further shape these dynamics in substantial ways.

van der Berg (

2020) documented pronounced differences between Dutch and Romanian teams, observing that Dutch teams demonstrated significantly higher levels of PS and knowledge sharing, potentially due to cultural norms that favor egalitarian dialogue and open feedback.

Cauwelier et al. (

2019) found that while higher PS correlates with increased learning behaviors and knowledge creation in American and French engineering teams, these patterns did not hold in Thai teams, where hierarchical norms and deference to authority may suppress open expression of uncertainty or dissent.

Yin et al. (

2019) showed that collectivist cultural values in China can reinforce the mediating role of PS by encouraging shared responsibility and group cohesion, facilitating a supportive environment for knowledge exchange.

Rivera et al. (

2020) emphasized that in Latin American manufacturing settings, a relational approach to PS—rooted in interpersonal warmth, respect, and personal trust—was particularly salient in promoting effective knowledge-sharing behaviors.

Implementation strategies to cultivate PS and strengthen KM require careful attention to leadership development, communication systems, and context-specific considerations.

van der Berg (

2020) highlighted the importance of cultivating strong leader-member exchange relationships that foster trust and openness.

Mancini and Ribiere (

2018) underscored the value of assertive conflict management practices, which can help teams surface differing viewpoints constructively while maintaining PS.

Cauwelier et al. (

2019) stressed that team learning initiatives must be tailored to cultural expectations around communication and hierarchy to be effective.

Agarwal and Anantatmula (

2022) identified clear organizational policies, transparent communication channels, and investment in employees’ psychological capital as essential enablers of sustained knowledge-sharing practices.

Rivera et al. (

2020) further emphasized that respect, empathy, and interpersonal trust are foundational conditions for any strategy aimed at embedding PS into the fabric of organizational culture.

Taken together, these findings indicate that successful KM initiatives require comprehensive and adaptive approaches that build and maintain PS. This includes developing supportive leadership practices that encourage open communication and learning from error, implementing clear and consistent communication policies that reduce ambiguity, designing context-sensitive strategies responsive to cultural norms and team dynamics, and creating opportunities for reflective learning and collaborative problem-solving. PS should therefore be regarded not only as a desirable attribute of organizational climate but as a strategic imperative for any organization seeking to enhance its knowledge capabilities, resilience, and adaptability in rapidly changing environments.

2.5. Impacts of Psychological Safety on Knowledge Management and Organizational Learning

As previously discussed, (

Section 2.1), PS creates an environment where employees are willing to share ideas and learn from mistakes. These mechanisms directly facilitate KM and sustain OL processes, for example through knowledge creation.

PS has its roots in organizational change studies, where it has been argued that it is essential for people to feel safe and able to deal with challenges and anxiety (

Ochiai & Otsuka, 2022). In this way, PS allows people to focus on group goals, be proactive in problem-solving and overcome self-protective strategies (

Bülbül et al., 2022). In a psychologically safe environment, employees feel free to share information and knowledge (

Newman et al., 2017), make suggestions for organizational improvements, and act autonomously to develop new products and services (

Bülbül et al., 2022).

One study even showed that team PS and knowledge sharing sequentially mediate the relationship between entrepreneurial leadership and team creativity (

Mehmood et al., 2022). This suggests that entrepreneurial leadership first creates a psychologically safe environment, which in turn facilitates knowledge sharing, leading to greater team creativity. In organizations operating in a complex and changing environment, PS is a crucial source of value creation, as it contributes to the creation and sharing of knowledge within organizations (

Bülbül et al., 2022). In addition, PS increases team and OL (

Newman et al., 2017).

The integration of the variables under study—PS, KM and OL—reveals a dynamic interplay that fosters learning cultures within organizations. PS emerges as the foundational element that enables employees to feel safe in openly sharing ideas and knowledge, which is essential for effective KM practices. In turn, KM facilitates the collective processing and dissemination of insights, reinforcing OL mechanisms. The literature review highlights that PS is not only interlinked with KM and OL but also serves as a strategic enabler for organizations aiming to adapt, innovate, and thrive in environments of continuous change.

3. Method

The study adopted a descriptive bibliometric design, complemented by a qualitative content analysis. In the first stage, the scientific output related to the constructs under analysis was identified; in the subsequent stage, the relationships among these constructs were further explored. Bibliometric research enables the identification, synthesis, and broad examination of the literature on a specific topic (

Öztürk et al., 2024).

To operationalise the analysis, data mining techniques and the VOSviewer software were employed (

Lundberg, 2024), a tool that enables the creation and analysis of bibliometric networks based on data extracted from scientific databases (

Lim et al., 2024). Data collection was conducted via the WoS platform, managed by the Institute for Scientific Information (ISI). This online service indexes the most highly cited scientific journals in their respective fields and provides the number of citations for each article over a given time period (

Clarivate, 2025). The analytical universe was defined as comprising articles published between 2000 and 2025.

The methodological orientation is hybrid: while grounded in bibliometric mapping, the study also incorporates conceptual clustering, thematic synthesis, and inductive theorizing supported by qualitative content analysis.

To structure the literature review strategy and ensure the rigorous selection of included studies, the SPIDER framework (Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation, Research type) was adopted, as it is commonly used in qualitative and mixed-method reviews (

Amir-Behghadami, 2021). Its operationalisation was based on the following criteria: (S) sample composed of articles addressing the constructs PS, KM, and OL, published between 2000 and 2025; (PI) focus on the relationships among these constructs and on the thematic categories emerging from the content analysis; (D) descriptive bibliometric design, complemented by qualitative content analysis, using data mining techniques and VOSviewer; (E) evaluation based on bibliometric indicators and qualitative categories resulting from the analysis; (R) empirical studies published in scientific journal format and indexed in the WoS (

Amir-Behghadami, 2021).

3.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The document analysis began with the application of the Boolean expression “Psychological safety” AND “Knowledge management” AND “Organizational learning” in the WoS database. Only peer-reviewed journal articles written in English were selected. The criteria guiding the inclusion and exclusion of studies were structured using the SPIDER framework and are summarised in

Table 1.

Following the definition of the SPIDER criteria, the search process was conducted in three stages. In the first stage, each construct was searched individually—PS, KM, and OL—in order to quantify the volume of records associated with each construct in isolation. To ensure comprehensiveness, synonyms and spelling variations for each construct were included (e.g., “psychological safety climate”, “knowledge sharing”, “organisational learning”). However, for ease of interpretation,

Table 2 presents only the three initially defined constructs.

In the second stage, the descriptors “psychological safety” and “knowledge management” were combined, which led to a reduction in the number of retrieved documents. In the third stage, “organizational learning” was added to the previous search string, resulting in a further decrease in the number of records. This stepwise procedure enabled the delimitation of a coherent and theoretically integrated corpus while avoiding the inclusion of studies that focused exclusively on a single construct.

In addition to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the following filters were also applied: Document Types, Publication Years, and Open Access. As such, only articles published between 2000 and 2025 with full-text open access were included. Books, book chapters, conference proceedings, master’s dissertations, doctoral theses, and articles that, upon abstract review, did not align with the research objectives were excluded.

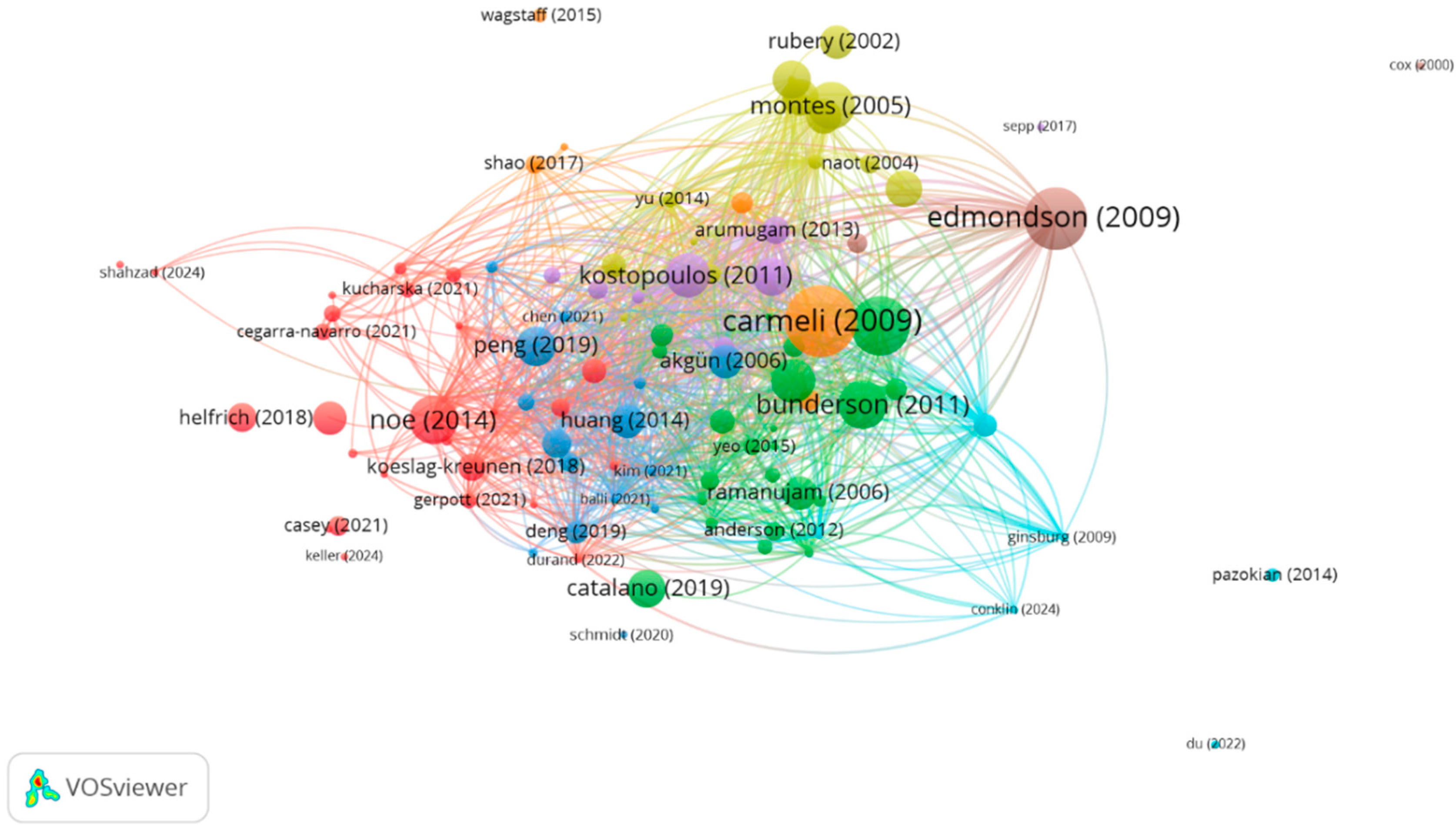

Figure 1 illustrates the co-citation network generated by VOSviewer (version 1.6.20), howing clusters of authors who frequently appear together in the literature on psychological safety, knowledge management, and organizational learning.

3.2. Study Selection

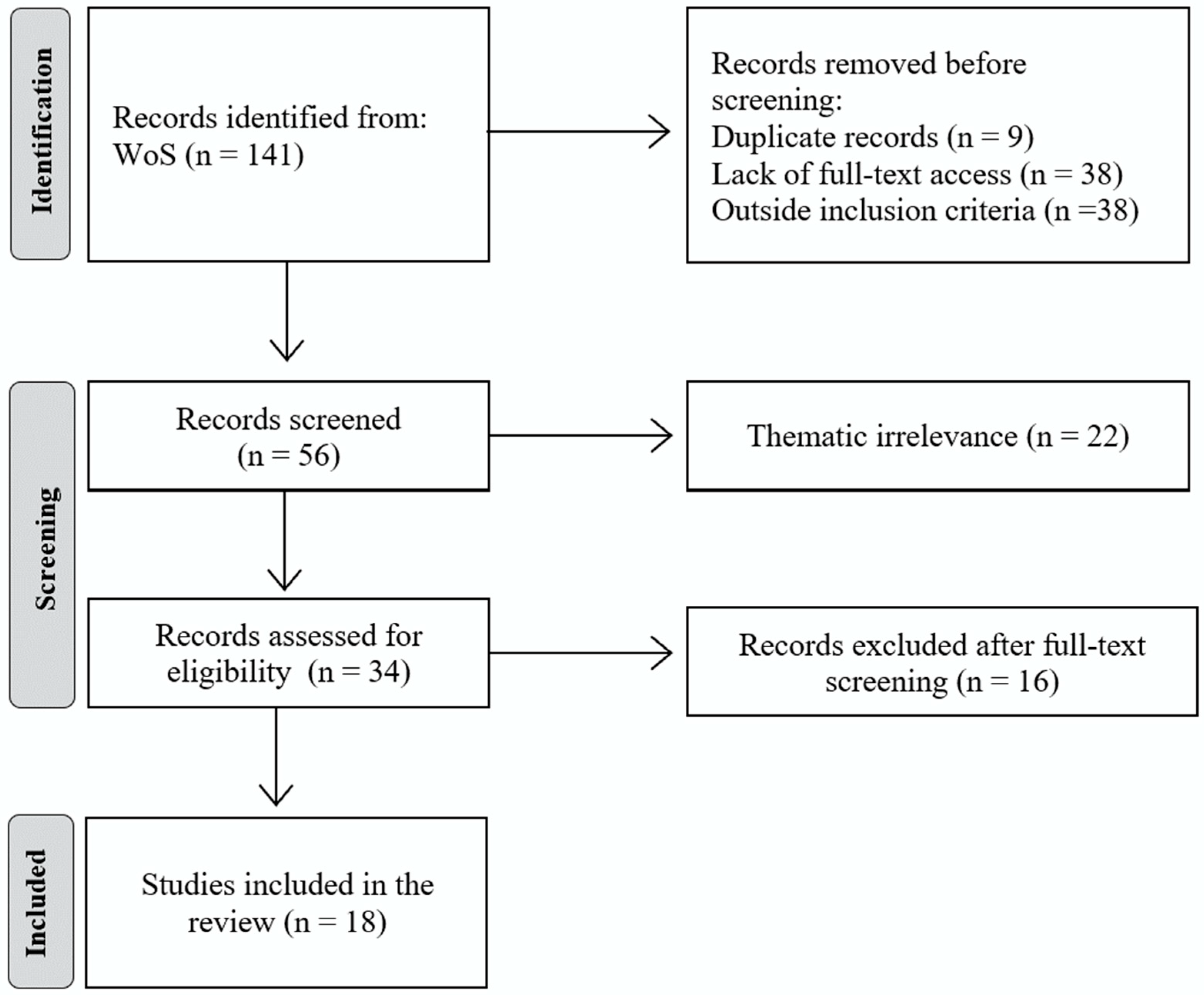

The search of the WoS Core Collection initially identified 141 records. Before screening, 47 records were removed: 9 duplicates, 38 without full-text access, and 38 outside the inclusion criteria. A total of 56 records were then screened by title and abstract, which resulted in the exclusion of 22 records due to thematic irrelevance. The remaining 34 records were assessed for eligibility through full-text reading, leading to the exclusion of 16 additional studies that did not meet the predefined inclusion criteria. Finally, 18 studies were included in the review. The entire selection process is illustrated in the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram (

Figure 2).

The main reasons for exclusion during screening and eligibility assessment were the absence of empirical data, superficial reference to the constructs without conceptual integration, or incomplete metadata, rather than the nature of the study results.

3.3. Data Extraction and Analysis

After applying the eligibility criteria and conducting a full-text review of the selected articles, the theoretical and empirical contributions of each study were analysed, with the aim of identifying conceptual patterns and recurring relationships among the constructs examined. This stage enabled the organisation of the information into a structured analysis grid, which subsequently facilitated the qualitative synthesis, and the development of a conceptual model grounded in the evidence extracted from the included articles.

The qualitative content analysis was conducted manually by the researchers, following a systematic thematic coding process. This involved the full-text reading of the included articles, the extraction of relevant text segments, and their categorization into subthemes, which were then grouped into broader categories. To ensure reliability and minimize bias, coding was carried out independently by two researchers and subsequently harmonized through consensus.

It is also important to note that, during the qualitative analysis, the categorization of certain subcategories—such as knowledge sharing—emerged directly from the coding of the full texts of the included articles. Although this concept is often addressed in the literature as a process of KM, the predominance of the analyzed studies (e.g.,

Newman et al., 2017;

Kucharska & Rebelo, 2022;

Shahzad et al., 2024) highlighted its essential function in transforming individual knowledge into collective routines, thereby justifying its placement within the domain of OL in the proposed conceptual model.

4. Results

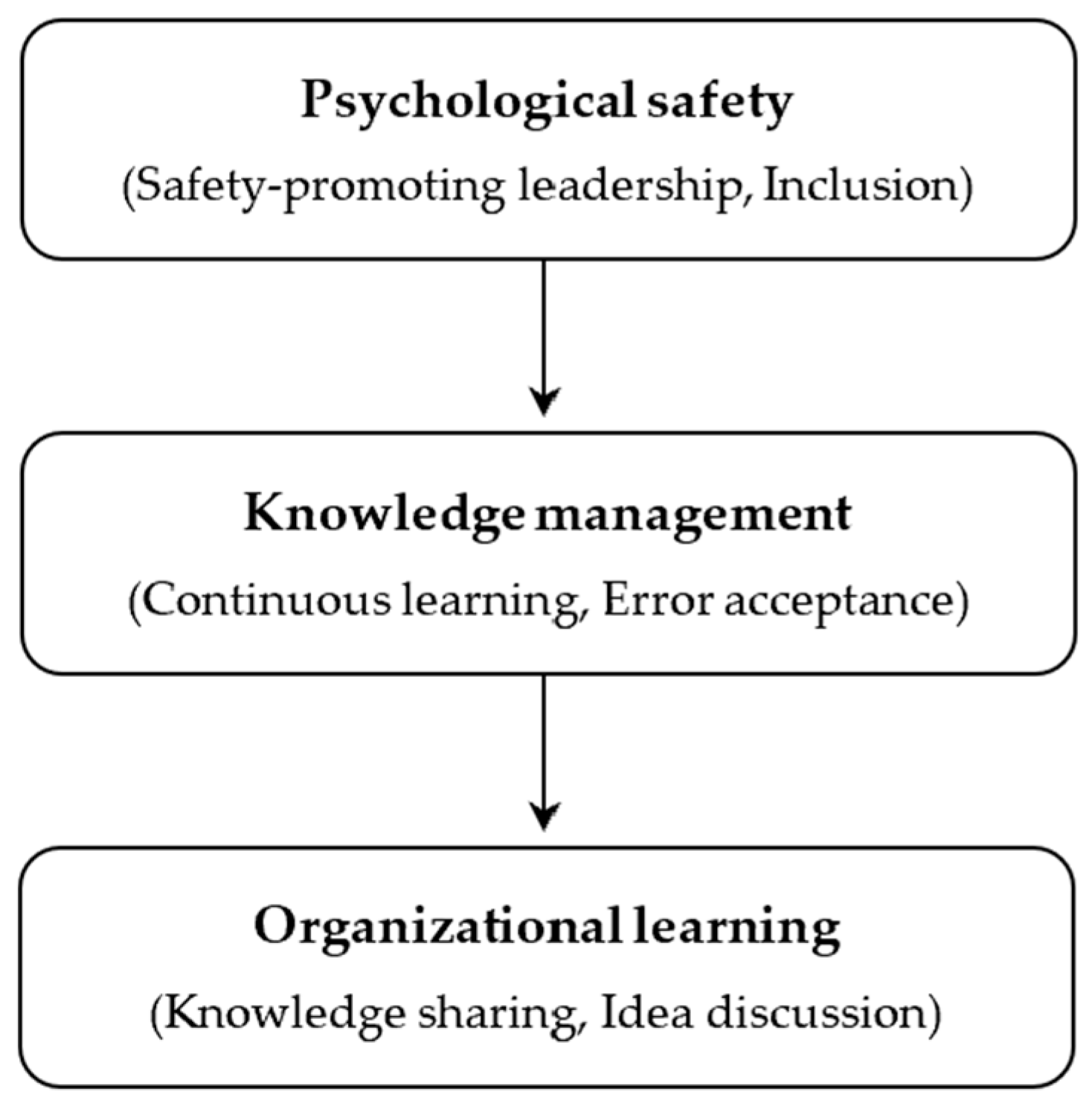

The content analysis of the 18 articles led to the development of a model that synthesises the relationships among the main constructs addressed (

Table 3). This model was developed inductively, based on the patterns identified in the analysed articles, and represents the mechanisms through which PS influences knowledge-sharing behaviours and learning processes within organisational settings.

The qualitative content analysis was conducted on the full texts of the 18 included articles, not limited to keywords or abstracts. Through systematic coding, we extracted recurring conceptual elements explicitly discussed in the studies, which were then grouped into nine subcategories (

Figure 3). This process allowed us to quantify their frequency of occurrence across the corpus. Notably, the PS climate appeared in 12 articles, collective learning was mentioned in 14 articles, and knowledge sharing was referenced in 11 articles.

This representation complements the analytical structure presented in

Table 4, which details the association between subcategories and their corresponding main categories. An overall balanced distribution is observed, reinforcing the consistency of the identified topics.

Each node represents an author and is connected to the themes addressed in the analysis. This type of visualisation allows for the observation of thematic concentration patterns, overlaps among authors, and areas of greater theoretical density.

Figure 4 presents a visual map of the thematic clusters identified through content analysis, based on the main contributions of each article included in the sample. Each color corresponds to a specific theme: the green cluster represents PS (e.g.,

Andersson et al., 2020;

A. C. Edmondson & Lei, 2014), the blue cluster represents KM (

Bunderson & Reagans, 2011;

Rubery et al., 2002), and the red cluster represents OL (

Cegarra-Navarro et al., 2021;

Kucharska, 2021). This visualization allows for the observation of thematic concentration patterns, overlaps among authors, and areas of greater theoretical density.

The co-citation analysis in the map reveals a well-defined thematic structure around three major conceptual axes: PS, KM, and OL learning. While the bibliometric outputs provide a structural overview, their relevance becomes clearer when connected to the theoretical perspectives of KM and OL.

The green cluster, centred on the work of

A. C. Edmondson and Lei (

2014), highlights the importance of PS as a foundation for interactive learning and innovation behaviours, reinforced by studies addressing leadership and interpersonal climate. The blue cluster groups studies on KM, with particular emphasis on the structural and relational challenges of sharing tacit and explicit knowledge in complex organisational contexts. The red cluster brings together research focused on organisational learning, especially the role of error acceptance, learning culture, and inclusive practices. The emphasis on error tolerance and inclusivity resonates with established OL paradigms, which underline the role of open and participatory environments in fostering collective learning.

The articulation between the three clusters suggests that PS is a critical antecedent of knowledge sharing, which, in turn, is fundamental for sustained organisational learning. These clusters illustrate how psychological safety fosters trust dynamics that are essential for knowledge sharing, which has long been emphasized in KM theories. Taken together, these bibliometric findings not only depict co-occurrence patterns but also highlight conceptual tensions that inform subsequent interpretation (

Figure 5).

The sample analysis revealed a predominance of studies focusing on PS, OL, and supportive leadership, underscoring the relevance of these themes in literature. Less frequently addressed were the categories of knowledge sharing, knowledge hiding/hoarding, error acceptance, and organisational inclusion. This distribution indicates that, although the fundamental pillars of organisational learning are present, there is a gap in studies that integrate error acceptance, organisational inclusion, and dysfunctional behaviours related to knowledge retention. This gap highlights the need for future research that explores, in greater depth, the interactions among these dimensions, particularly in the context of building safe, inclusive, and learning-oriented organisational cultures.

The analysis carried out made it possible not only to identify recurring patterns among the constructs under study but also to propose a conceptual model that synthesises the relationships identified in the literature. This model highlights the central role of PS in promoting knowledge sharing and, consequently, in consolidating OL. Although knowledge sharing is often conceptualized as a core process of KM, both our qualitative analysis and the reviewed literature (e.g.,

Kucharska & Rebelo, 2022;

Newman et al., 2017;

Shahzad et al., 2024) indicate that its primary function lies in transforming individual knowledge into collective practices and organizational routines. For this reason, it was represented in the model as a mechanism underpinning OL. By integrating dimensions such as supportive leadership, inclusion, and error acceptance, the findings underscore the importance of building organizational cultures that foster mutual trust, continuous development, and collective learning.

At the same time, the persistence of knowledge-hiding practices, even under conditions of enhanced psychological safety, points to enduring tensions within organizations. Leadership support thus emerges as a decisive factor in shaping KM practices and mitigating these contradictions.

5. Discussion

This study aimed to reflect on the pathways that connect PS, KM, and OL, as well as the processes through which these constructs interrelate and reinforce each other in organisational settings. Based on the conceptual model developed and the analysis of the selected studies, the objective was to understand how these factors contribute to the construction of more collaborative, innovative, and sustainable organisational cultures.

PS has been widely recognised as one of the main facilitators of knowledge sharing within organisations, particularly in relation to tacit knowledge, whose transmission depends on trust, openness, and reciprocity (

Newman et al., 2017). The studies by

Rivera et al. (

2020) show that inclusive work environments, with leadership that promotes active listening, tolerance for mistakes, and recognition of individual differences, foster an organisational climate conducive to learning and innovation.

Within this framework,

Kucharska and Rebelo (

2022) argue that PS decreases the tendency to withhold knowledge, such as through knowledge hiding (active refusal) and knowledge hoarding (passive retention). These behaviours, often driven by insecurity, competition, or lack of trust, can be mitigated through organisational practices that enhance a sense of belonging and mutual appreciation (

Paulus, 2023). Organisational inclusion thus emerges as a key mechanism that, by reinforcing group cohesion and mutual trust, strengthens PS, thereby reducing the likelihood of these dysfunctional behaviours (

Cheng et al., 2024). Similarly,

B. Kim and Kim (

2024) emphasise that environments where mistakes are accepted foster greater openness to knowledge sharing by reducing the fear of exposure and judgment. This process is also shaped by individual factors, such as learning orientation, which moderates the relationship between inclusion and sharing behaviour (

Dweck & Leggett, 2018). PS is more than a relational condition—it constitutes a critical organisational resource for the effectiveness of collective knowledge and the sustainability of learning (

Rodrigues & Figueiredo, 2025).

The data obtained show that PS does not operate in isolation but in conjunction with inclusive leadership practices, error acceptance, and development-oriented organisational cultures (

Kucharska & Rebelo, 2022). In this context,

Paulus (

2023) notes that environments marked by rigid hierarchies and low openness to divergent views hinder the flow of tacit knowledge and limit collective learning.

Thematic analysis also revealed that error acceptance, although less frequently addressed in the analysed studies, is a relevant predictor of knowledge sharing (

Kucharska & Rebelo, 2022). When mistakes are viewed as opportunities for growth, they create a secure emotional foundation that enhances learning from experience. This conclusion aligns with the findings of

Mehmood et al. (

2022), who demonstrate that entrepreneurial leadership generates PS, which in turn facilitates knowledge sharing and stimulates team creativity.

It is important to note that, although organisational learning emerged as the least consolidated construct in the reviewed literature, it plays a central role as the outcome of the proposed model (

Newman et al., 2017). This centrality derives from the fact that knowledge sharing—enabled by PS—functions as the key mechanism through which collective learning takes place (

Kucharska & Rebelo, 2022). These findings are consistent with the work of

Shahzad et al. (

2024), who underscore the importance of interpersonal relationships and transformational leadership in fostering collaborative learning environments.

In this regard, the emphasis on the concept of collective learning, mentioned in eight of the articles analysed, reinforces the idea that team learning is not limited to the individual acquisition of skills, but involves a relational process sustained by mutual trust, openness to critique, and shared knowledge construction (

Andersson et al., 2020).

Cegarra-Navarro et al. (

2021) further support this perspective by showing that teams with high levels of PS exhibit greater capacity to adapt and internalise experiential knowledge.

Despite the robustness of the patterns identified, some aspects remain underexplored in empirical literature. A significant gap was identified concerning the interdependence between organisational inclusion, error acceptance, and knowledge hiding dynamics. While studies such as those by

Cheng et al. (

2024) and

B. Kim and Kim (

2024) offer relevant contributions, an integrated articulation of these dimensions remains limited, making it difficult to fully understand the factors that sustain organisational cultures truly open to error, dialogue, and continuous learning.

The interdependence between PS, KM, and OL also provides a theoretical foundation for understanding how learning-oriented cultures contribute to organizational resilience. In psychologically safe environments, employees are more likely to share mistakes, reflect on failures, and collectively adjust practices, which enhances the organization’s capacity to recover and adapt in volatile contexts. Thus, resilience emerges as both a consequence and a catalyst of continuous learning processes, reinforcing the cyclical nature of adaptive organizational systems.

The results suggest that building organisational learning cultures requires more formal systems or KM technologies (

Cegarra-Navarro et al., 2021). It especially demands an ethical and intentional commitment to creating psychologically safe, inclusive, and human-development-oriented work environments (

Paulus, 2023). PS thus transcends its relational dimension and affirms itself as a strategic organisational asset essential to sustaining practices of knowledge sharing, continuous learning, and innovation (

Jin & Peng, 2024).

6. Conclusions and Future Research

This study aimed to map and analyse the relationships among PS, KM, and OL, using a bibliometric and qualitative approach based on 18 articles indexed in the WoS. The findings enabled the development of a conceptual model that highlights the central role of PS as a facilitator of knowledge sharing, which, in turn, sustains OL. This theoretical integration helps to bridge gaps in a frequently fragmented literature and offers a structured perspective on the mechanisms that promote inclusive, innovative, and learning-oriented organisational cultures.

The main theoretical contribution of this work lies in the articulation of three constructs that, although interdependent, have often been analysed in isolation. The proposed model demonstrates that knowledge sharing—mediated by factors such as supportive leadership, error acceptance, and organisational inclusion—relies on high levels of PS. More than a favourable organisational climate, PS emerges as a strategic asset essential for resilience, collective performance, and innovation in complex organisational environments.

From a practical standpoint, the findings suggest that building effective learning cultures requires more than technical KM systems. Above all, it demands investment in inclusive leadership practices, the development of relational competencies, the promotion of interpersonal trust, and the recognition of diversity as an organisational value. In this sense, organisations that prioritise psychologically safe environments tend to mobilise the collective potential of their employees, enhancing not only innovation but also adaptability in the face of change.

Despite its contributions, this study presents certain limitations. The final corpus of 18 articles, although relatively small, results from strict inclusion and exclusion criteria that enhance the internal validity of the findings. However, this sample size limits the generalizability of the results across diverse organizational and cultural contexts. Moreover, most studies focused on specific cultural settings, raising concerns about the broader applicability of the findings. One limitation concerns the exclusion of 38 articles during the full-text screening stage. Although this number is significant, the exclusions were strictly based on methodological or conceptual inadequacy relative to the predefined criteria and not on study outcomes. Therefore, we consider that no systematic bias was introduced that could compromise the validity of the findings, although the final sample became more restricted.

For future research, we recommend expanding empirical analyses to different sectors and regions, with particular attention paid to the intercultural dynamics of PS. Further studies should also apply longitudinal approaches to examine evolving knowledge flows and integrate digital collaboration contexts into PS–KM–OL dynamics. Moreover, it would be relevant to investigate the combined effects of variables such as transformational leadership, psychological capital, and organisational maturity in promoting sustained knowledge sharing and learning practices. Such studies could deepen our understanding of how psychologically safe environments mitigate knowledge hiding, sustain organisational learning, and consolidate a learning culture rooted in trust and inclusion over time.

Theoretically, this study contributes to perspectives such as the knowledge-based view of the firm, absorptive capacity, and experiential learning theories by linking psychological safety, knowledge management, and organisational learning in an integrative conceptual model. From a practical perspective, the findings suggest that managers, HR professionals, and leaders should foster error-tolerant environments, embed psychological safety into leadership development, and design interventions that minimise knowledge-hiding behaviours.

Overall, this study reinforces the importance of viewing PS not only as a desirable climate but also as a structural pillar for organisations that learn, innovate, and adapt sustainably. Promoting relational well-being in the workplace has become a necessary condition for fostering collective intelligence and organisational resilience.

In practical terms, the findings of this study can be operationalized across different organizational levels. At the leadership level, training programs in inclusive and psychologically safe leadership are particularly relevant, as they encourage practices such as valuing employee voice, tolerating mistakes, and promoting constructive feedback. Within human resource policies, psychological safety can be embedded as a criterion in performance appraisal processes, recognition programs, and career development initiatives. In the field of knowledge management, the establishment of formal systems for knowledge sharing, such as communities of practice or collaborative digital platforms, proves essential for aligning knowledge exchange with cultures of trust and learning. Finally, at the cultural level, the implementation of awareness programs and codes of conduct that foster openness, diversity, and cross-functional cooperation can help consolidate organizational environments oriented toward continuous learning. In this way, the contributions of this study extend beyond the academic sphere and translate into concrete and feasible recommendations that enable organizations to strengthen resilience, enhance collective learning, and foster sustained innovation.