Types of Knowledge Transferred Within International Interfirm Alliances in the Nigerian Oil Industry and the Potential to Develop Partners’ Innovation Capacity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Interfirm Collaborations in the Nigerian Oil Industry

3. Literature Review

3.1. Interfirm Collaboration and Knowledge Transfer

3.2. Knowledge as the Object of Learning/Knowledge Transfer in Interfirm Collaborations

3.3. Knowledge Acquisition/Transfer in International Interfirm Collaborations

4. Empirical Research Method

4.1. Research Strategy and Operationalisation

4.2. Data Collection and Analysis

5. Findings

5.1. The Four Cases of Interfirm Collaborations

| Cases and Findings | ||

|---|---|---|

| Cases of Interfirm Alliances | Knowledge Transfer/Acquisition Activities | |

| Local Alliance Partner | Foreign Alliance Partner | |

Case 1

|

|

|

Case 2

|

|

|

Case 3

|

|

|

Case 4

|

|

|

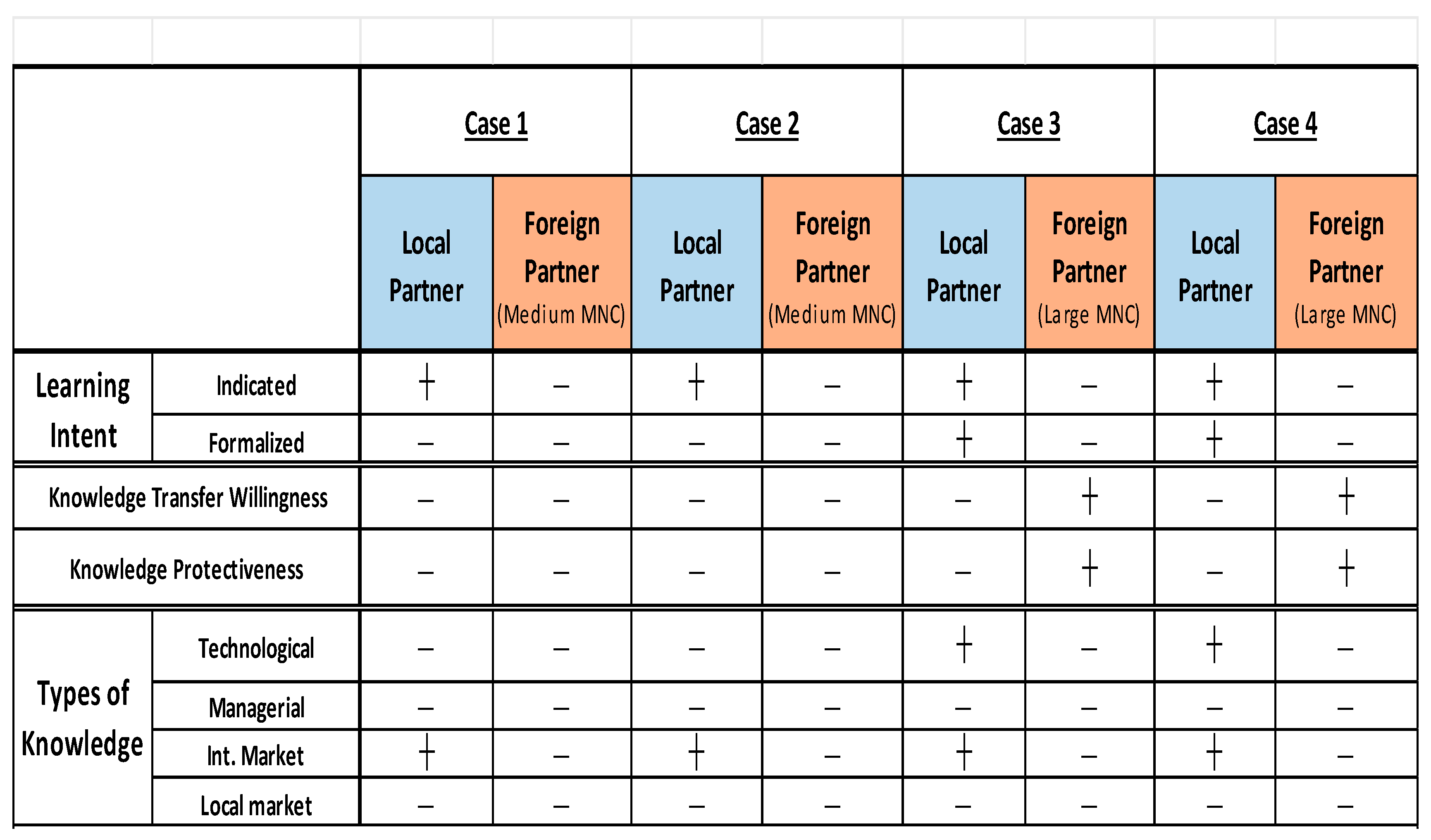

5.2. Learning Intent, Knowledge Transfer Willingness, and Knowledge Protectiveness

5.3. Knowledge Types

“[…] in terms of international (market) knowledge, we now know where and where we can sell our crude oil, because we have done that with our technical partners before, and we are doing it now on our own. Now we can go to AIM market in London to get investment, all those are part of international knowledge. Now we can go to Citibank, HSBC, or Barclays bank in London to source for fund, all these are part of the international knowledge we acquired”.(1LP-Manager (Op.), QU: 2:45)

“[…] the company currently handling our crude was not too keen to have a sale agreement with us. But they were keen to have agreement with our technical partner, who is a publicly quoted company in ‘North America’ [……] it was easy to do due diligence on ‘our technical partner’. So, the sales contract we have now is through ‘the technical partner’. So, from that point of view, my company is gaining from that kind of knowledge and this exposure to international market”.(2LP-Managing Director, QU: 1:45)

“[…] yes, in terms of ‘Boeing construction and fabrication’, we have learned a lot […]. And, also, in the area of ‘reservoir studies’ too; we have also gained practical experience in “reservoir determination” and things like that […]”.(3LP-Manager, QU: 1: 46–48)

“[……] we have acquired good knowledge from the relationship, because before then, you see, we have been doing engineering design, but we do it just to support our in-house maintenance work and small construction work. But today, we have a complete outfit, that first, boasts over 100 design engineers, [……], and the partnership has really pushed to the international standard. So, whatever we are designing today, we are not only designing for small operators here; we are designing something that even in Houston (USA) will be applicable. And the thing is that we have even the opportunity to do detailed engineering for HHI (HYUNDAI) based in Korea……”.(4LP-Deputy Director, QU:1:46)

“[……] but knowledge and technology are transferred more at the technical level, at the management (level) not much. You can see, if you look at it, everybody is silent about the top, but the top controls everybody; so the focus on management training has not been very much, everybody is talking about the technical, but I see a situation that we need to do more on management side also, so that the two would move together”.(4LP-Deputy Director, QU: 1:50)

6. Analysis, Discussion, and Propositions

7. Conclusions and Recommendations

7.1. Conclusions

7.2. Policy/Managerial Implications

7.3. Research Implications

7.4. Limitations of the Study

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Acharya, C., Ojha, D., Gokhale, R., & Patel, P. C. (2022). Managing information for innovation capability: The role of boundary spanning objects using knowledge integration. International Journal of Information Management, 62, 102438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ado, A., Su, Z., & Wanjiru, R. (2017). Learning and knowledge transfer in Africa-China JVs: Interplay between informalities, culture, and social capital. Journal of International Management, 23(2), 166–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agoro, B. (2001). Impediments to expansion: Why is the upstream sector of Nigeria’s petroleum industry not growing? Journal of Energy and Natural Resources Law, 19(1), 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amankwah-Amoah, J., Adomako, S., Joseph Kwadwo Danquah, J. K., Opoku, R. A., & Zahoor, N. (2022). Foreign market knowledge, entry mode choice and SME international performance in an emerging market. Journal of International Management, 28(4), 100955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosini, V., & Bowman, C. (2001). Tacit knowledge: Some suggestions for operationalization. Journal of Management Studies, 38(6), 811–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkema, H. G., Bell, J. H. J., & Pennings, J. M. (1996). Foreign entry, cultural barriers, and learning. Strategic Management Journal, 17(2), 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. B. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beamish, P. W. (1988). The characteristics of joint ventures in developed and developing countries. Columbia Journal of World Business, 1985, 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Becerra, M., Lunnan, R., & Huemer, L. (2008). Trustworthiness, risk, and the transfer of tacit and explicit knowledge between alliance partners [Special issue]. Journal of Management Studies, 45(4), 675–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengoa, D., & Kaufmann, H. (2016). The influence of trust on the trilogy of knowledge creation, sharing and transfer. Thunderbird International Business Review, 58(3), 239–249. [Google Scholar]

- Bıçakcıoğlu-Peynirci, N. (2023). Internationalization of emerging market multinational enterprises: A systematic literature review and future directions. Journal of Business Research, 164, 114002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boadu, F., Xie, Y., Du, Y.-F., & Dwomo-Fokuo, E. (2018). MNEs subsidiary training and development and firm innovative performance: The moderating effects of tacit and explicit knowledge received from headquarters. Sustainability, 10(11), 4208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, T. (2007). Local knowledge resources and knowledge flows. Industry and Innovation, 14(2), 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanova, L., & Miroux, A. (2018). Emerging market multinationals reshaping the business landscape. Transnational Corporation Review, 10(4), 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H., Nunes, M. B., Ragsdell, G., & An, X. (2018). Extrinsic and intrinsic motivation for experience grounded tacit knowledge sharing in Chinese software organisations. Journal of Knowledge Management, 22(2), 478–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Child, J., & Markórczy, L. (1993). Host-country managerial behaviour and learning in Chinese and Hungarian joint ventures. Journal of Management Studies, 30(4), 611–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, J. D., & Hitt, M. A. (2006). Leveraging tacit knowledge in alliances: The importance of using relational capabilities to build and leverage relational capital. Journal of Engineering and Technology Management, 23(3), 147–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanaraj, C., Lyles, M. A., Steensma, K. H., & Tihanyi, L. (2004). Managing tacit and explicit knowledge transfer in IJVs: The role of relational embeddedness and the impact on performance. Journal of International Business Studies, 35(5), 428–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easterby-Smith, M., Lyles, M. A., & Tsang, E. W. K. (2008). Inter-organisational knowledge transfer: Current themes and future prospects. Journal of Management Studies, 45, 677–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K. M., & Graebner, M. E. (2007). Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. Academy of Management Journal, 50(1), 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, K., Johanson, J., Majkgard, A., & Sharma, D. (1997). Experiential knowledge and cost in the internationalization process. Journal of International Business Studies, 28(2), 337–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, K., Johanson, J., Majkgard, A., & Sharma, D. (2000). Effect of variation on knowledge acquisition in the internationalization process. International Studies of Management and Organization, 30(1), 26–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erramilli, M. K., & Rao, P. (1990). Choice of foreign market entry mode by service firms: Role of market knowledge. Management International Review, 30(2), 135–150. [Google Scholar]

- Fores, B., & Camison, C. (2016). Does incremental and radical innovation performance depend on different types of knowledge accumulation capabilities and organizational size? Journal of Business Research, 69, 831–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamble, J. R. (2020). Tacit vs explicit knowledge as antecedents for organizational change. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 33(6), 1123–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geisler, E. (2007). The metrics of knowledge: Mechanisms for preserving the value of managerial knowledge. Business Horizons, 50, 467–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godin, B. (2006). The knowledge-based economy: Conceptual framework or buzzword? Journal of Technology Transfer, 31, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, R. M. (1996a). Prospering in dynamically competitive environments: Organizational capability as knowledge integration. Organization Science, 7(4), 375–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, R. M. (1996b). Towards a knowledge-based theory of the firm [Winter special issue]. Strategic Management Journal, 17, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, R. M., & Baden-Fuller, C. (1995). A knowledge-based theory of interfirm collaboration. Academy of Management Journal, 1995, 109–122. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, R. M., & Baden-Fuller, C. (2004). Knowledge accessing theory of strategic alliances. Journal of Management Studies, 41(1), 61–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamel, G. (1991). Competition for competence and inter-partner learning within international strategic alliances. Strategic Management Journal, 12(S1), 83–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrigan, K. R. (1988). Strategic alliances and partner asymmetries. Management International Review, 28, 53–72. [Google Scholar]

- Hindle, C., & Woldemichael, D. (2009). Nigeria: Africa’s energy giant. Global business report. A special report from oil and gas investor and global business reports. Available online: https://gbreports.com/publication/nigeria-oil-gas-2009-ogi-release (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Howells, J., James, A., & Malik, K. (2003). The sourcing of technological knowledge: Distributed innovation processes and dynamic change. R&D Management, 33(4), 395–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IGF—Intergovernmental Forum on Mining, Minerals, Metals and Sustainable Development. (2018). Nigeria: National capacity—Building capacity in the oil sector through “indigenization” policies (case study). In IGF guidance for governments: Leveraging local content decisions for sustainable development. IISD. [Google Scholar]

- Inkpen, A. C. (1998). Learning and knowledge acquisition through international strategic alliances. Academy of Management Executive, 12(4), 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inkpen, A. C. (2000). Learning through joint ventures: A framework of knowledge acquisition. Journal of Management Studies, 37(7), 1019–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inkpen, A. C. (2008). Managing knowledge transfer in international alliances. Thunderbird International Business Review, 50(2), 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inkpen, A. C., & Beamish, P. W. (1997). Knowledge, bargaining power, and the instability of international joint ventures. Academy of Management Review, 22(1), 177–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inkpen, A. C., & Crossan, M. (1995). Believing is seeing: Joint venture and organizational learning. Journal of Management Studies, 32(5), 595–618. [Google Scholar]

- Inkpen, A. C., & Dinur, A. (1998). Knowledge management processes and international joint ventures. Organization Science, 9, 454–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inkpen, A. C., & Tsang, E. W. K. (2005). Social capital, networks, and knowledge transfer. Academy of Management Review, 1, 146–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johanson, J., & Vahlne, J.-E. (1977). The internationalization process of a firm. A model of knowledge development and increasing foreign market commitments. Journal of International Business Studies, 8(1), 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kale, P., & Anand, J. (2006). The decline of emerging economy joint ventures: The case of India. California Management Review, 48(3), 62–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Käss, S., Brosig, C., Westner, M., & Strahringer, S. (2024). Short and sweet: Multiple mini case studies as a form of rigorous case study research. Information Systems and e-Business Management, 22, 351–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.-S., & Inkpen, A. C. (2005). Cross-border R&D alliances, absorptive capacity and technology learning. Journal of International Management, 11(3), 313–329. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H., Park, B. I., Al-Tabbaa, O., & Khan, Z. (2024). Knowledge transfer and protection in international joint ventures: An integrative review. International Business Review, 33, 102300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogut, B. (1988). Joint venture: Theoretical and empirical perspectives. Strategic Management Journal, 9, 319–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogut, B., & Zander, U. (1992). Knowledge of the firm, combinative capabilities, and the replication of technology. Organization Science, 3(3), 383–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogut, B., & Zander, U. (1996). What firms do? Coordination, identity, and learning. Organization Science, 7(5), 502–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohtamäki, M., Rabetino, R., & Huikkola, T. (2023). Learning in strategic alliances: Reviewing the literature streams and crafting the agenda for future research. Industrial Marketing Management, 110, 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucharska, W., & Erickson, G. S. (2023). Tacit knowledge acquisition & sharing, and its influence on innovations: A Polish/US cross-country study. International Journal of Information Management, 71, 102647. [Google Scholar]

- Lane, P., & Lubatkin, M. (1998). Relative absorptive capacity and inter-organizational learning. Strategic Management Journal, 19, 461–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, P., Salk, J. E., & Lyles, M. A. (2001). Absorptive capacity, learning, and performance in international joint ventures. Strategic Management Journal, 22(12), 1139–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, R., Bengtsson, L., Henriksson, K., & Sparks, J. (1998). The interorganizational learning dilemma: Collective knowledge development in strategic alliances. Organization Science, 9(3), 285–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavie, D. (2006). The competitive advantage of interconnected firms: An extension of the resource-based view. Academy of Management Review, 31(3), 638–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, B., & Potter, A. (2012). Determinants of knowledge transfer in interfirm new product development projects. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 32(10), 1228–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, D., Slocum, J. W., & Pitts, R. A. (1997). Building cooperative advantage: Managing strategic alliances to promote organizational learning. Journal of World Business, 32(3), 203–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J., & Shenkar, O. (2003). Knowledge search and governance choice: International joint ventures in People’s Republic of China [Special issue]. Management International Review, 43(3), 91–109. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T., & Calantone, R. J. (1998). The impact of market knowledge on new product advantage: Conceptualization and empirical examination. Journal of Marketing, 62, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X. (2005). Local partner acquisition of managerial knowledge in international joint ventures: Focusing on foreign management control. Management International Review, 45(2), 219–237. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z., & Han, X. (2012). The process of organization and dynamic of evolution of tacit knowledge on innovation talents’ growth research. In G. Lee (Ed.), Advances in computational environment science (pp. 177–184). Springer Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyles, M. A., & Salk, J. E. (1996). Knowledge Acquisition from foreign parents in international joint ventures: An empirical examination in the Hungarian context. Journal of International Business Studies, 27(5), 877–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makino, S., & Delios, A. (1996). Local knowledge transfer and performance: Implications for alliance formation in Asia. Journal of International Business Studies, 27(5), 905–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makino, S., & Inkpen, A. C. (2003). Knowledge seeking FDI and learning across borders. In M. Easterby-Smith, M. A. Lyles, & M. Crossan (Eds.), The Blackwell handbook of organizational learning and knowledge management (pp. 233–252). Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Manhart, M., & Thalmann, S. (2015). Protecting organizational knowledge: A structured literature review. Journal of Knowledge Management, 19(2), 190–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEvily, B., & Marcus, A. (2005). Embedded ties and the acquisition of competitive capabilities. Strategic Management Journal, 26, 1033–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook (2nd ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Mowery, D. C., Oxley, J. E., & Silverman, B. S. (1996). Strategic alliances and knowledge transfer [Winter special issue]. Strategic Management Journal, 17, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthuveloo, R., Shanmugam, N., & Teoh, A. P. (2017). The impact of tacit knowledge management on organizational performance: Evidence from Malaysia. Asia Pacific Management Review, 22(4), 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narteh, B. (2008). Knowledge transfer in developed-developing country interfirm collaborations: A conceptual framework. Journal of Knowledge Management, 12(1), 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonaka, I., & Takeuchi, H. (1995). The knowledge-creating company: How Japanese companies create the dynamics of innovation. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Norman, P. M. (2002). Protecting knowledge in strategic alliances. Resource and relational characteristics. Journal of High Technology Management Research, 13, 177–202. [Google Scholar]

- Nwankwo, E., & Iyeke, S. (2022). Analysing the impact of oil and gas local content laws on engineering development and the GDP of Nigeria. Energy Policy, 163, 112836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okonkwo, O. (2018). Knowledge transfer in collaborations between foreign and indigenous firms in the Nigerian oil industry: The role of partners’ motivational characteristics. Thunderbird International Business Review, 61, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladipo, O. (2022, June 15). Marginal fields: Local companies voyage to first oil. BusinessDay Nigeria Newspaper Report. Available online: https://businessday.ng/energy/oilandgas/article/marginal-fields-local-companies-voyage-to-first-oil/ (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Oladipo, O. (2025, May 21). Nigeria retains 56% of oil industry spend as local content deepens. BusinessDay Nigeria Newspaper Report. Available online: https://businessday.ng/energy/oilandgas/article/nigeria-retains-56-of-oil-industry-spend-as-local-content-deepens/ (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Osabutey, E., Williams, K., & Debrah, Y. (2014). The potential for technology and knowledge transfers between foreign and local firms: A study of the construction industry in Ghana. Journal of World Business, 49(4), 560–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C., Ghauri, P. N., Lee, J. Y., & Golmohammadi, I. (2022). Unveiling the black box of IJV innovativeness: The role of explicit and tacit knowledge transfer. Journal of International Management, 28, 100956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C., Vertinsky, I., & Becerra, M. (2015). Transfers of tacit vs. explicit knowledge and performance in international joint ventures: The role of age. International Business Review, 24(1), 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Nordtvedt, L., Kedia, B. L., Datta, D. K., & Rasheed, A. A. (2008). Effectiveness and efficiency of cross-border knowledge transfer: An empirical examination. Journal of Management Studies, 45(4), 714–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rammal, H. G., Rose, E. L., & Ferreira, J. J. (2023). Managing cross-border knowledge transfer for innovation: An introduction to the special issue. International Business Review, 32(2), 102098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sammarra, A., & Biggiero, L. (2008). Heterogeneity and specificity of interfirm knowledge flows in innovation networks [Special issue]. Journal of Management Studies, 45(4), 800–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seny Kan, K. A., Apitsa, S. M., & Adegbite, E. (2015). African management: Concept, content and usability. Society and Business Review, 10(3), 258–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenkar, O., & Li, J. (1999). Knowledge in international cooperative ventures. Organization Science, 10(2), 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikombe, S., & Phiri, M. A. (2019). Exploring tacit knowledge transfer and innovation capabilities within the buyer–supplier collaboration: A literature review. Cogent Business & Management, 6(1), 1683130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonin, B. L. (1999). Transfer of marketing know-how in international strategic alliances: An empirical investigation of the role and antecedents of knowledge ambiguity. Journal of International Business Studies, 30(3), 463–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonin, B. L. (2004). An empirical investigation of the process of knowledge transfer in international strategic alliances. Journal of International Business Studies, 35(5), 407–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stake, R. E. (2006). Multiple case study analysis. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Szulanski, G. (1996). Exploring internal stickiness: Impediments to the transfer of best practice within the firm [Winter special issue]. Strategic Management Journal, 17, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, E. W. K. (1999). A preliminary typology of learning in international strategic alliances. Journal of World Business, 34(3), 211–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, E. W. K. (2001). Managerial learning in foreign-invested enterprises of China. Management International Review, 41(1), 29–51. [Google Scholar]

- Tsourakis, F. (2022). Nigeria: How marginal fields are generating new opportunities. In-VR energy consultancy. Available online: https://www.in-vr.co/articles/nigeria-how-marginal-fields-are-generating-new-opportunities (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- UNCTAD—United Nations Conference on Trade and Development & CALAG Capital Limited. (2006). African oil and gas services sector survey: Volume 1: Creating local linkages by empowering indigenous entrepreneurs. United Nations Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Y., & Child, J. (2002). An analysis of strategic determinants, learning and decision-making in sino-british joint ventures. British Journal of Management, 13(2), 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q., Mudambi, R., & Meyer, K. (2008). Conventional and reverse knowledge flows in multinational corporations. Journal of Management, 34(5), 882–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R. K. (2009). Case study research: Design and methods (4th ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

| Knowledge Areas Dimension | |

|---|---|

| Knowledge Areas | Components |

| Technological |

|

| Managerial |

|

| Market |

|

| Explicit–Tacit Dimension | ||

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge Areas | Explicit | Tacit |

| Technological |

|

|

| Managerial |

|

|

| Market |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Okonkwo, O.C. Types of Knowledge Transferred Within International Interfirm Alliances in the Nigerian Oil Industry and the Potential to Develop Partners’ Innovation Capacity. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 423. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15110423

Okonkwo OC. Types of Knowledge Transferred Within International Interfirm Alliances in the Nigerian Oil Industry and the Potential to Develop Partners’ Innovation Capacity. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(11):423. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15110423

Chicago/Turabian StyleOkonkwo, Okechukwu C. 2025. "Types of Knowledge Transferred Within International Interfirm Alliances in the Nigerian Oil Industry and the Potential to Develop Partners’ Innovation Capacity" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 11: 423. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15110423

APA StyleOkonkwo, O. C. (2025). Types of Knowledge Transferred Within International Interfirm Alliances in the Nigerian Oil Industry and the Potential to Develop Partners’ Innovation Capacity. Administrative Sciences, 15(11), 423. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15110423