The Influence of Organizational Climate on Work Engagement: Evidence from the Greek Industrial Sector

Abstract

1. Introduction

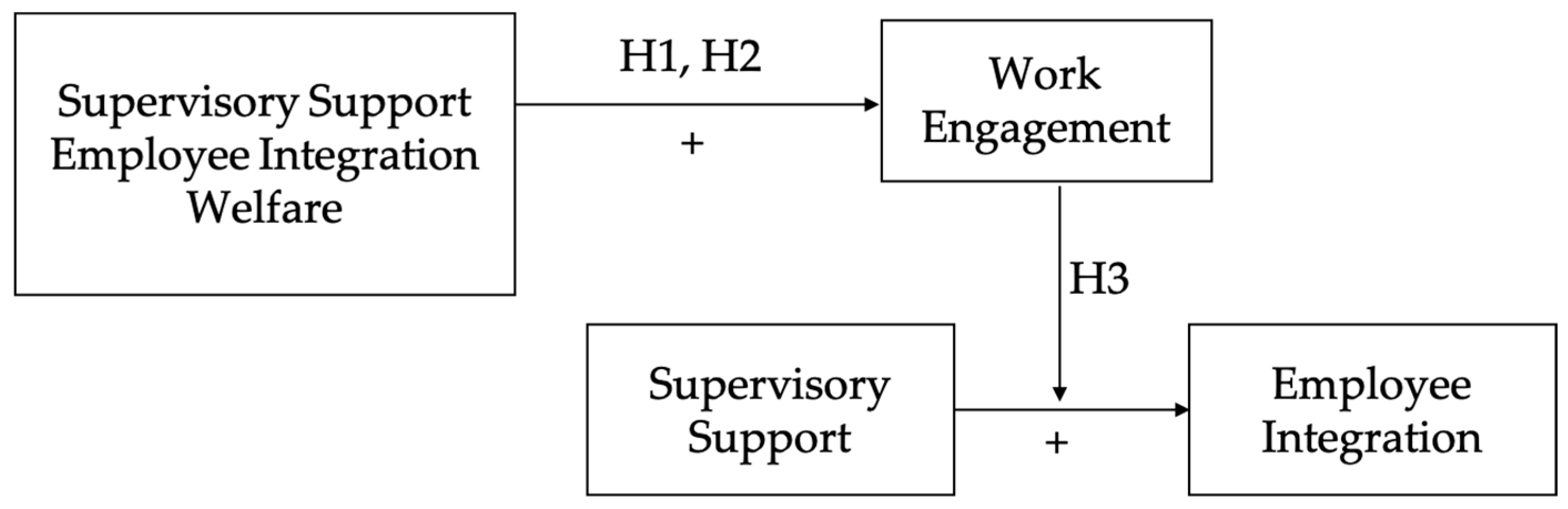

2. Theoretical Framework & Hypotheses Development

2.1. Theoretical Foundation of Organizational Climate and Work Engagement

2.2. Exploring the Interrelationship Between Organizational Climate and Work Engagement

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Procedure and Participants

3.2. Measures

4. Results

4.1. Relationship Between Organizational Climate and Work Engagement

4.2. Associations Between Psychological Climate Facets and Work Engagement

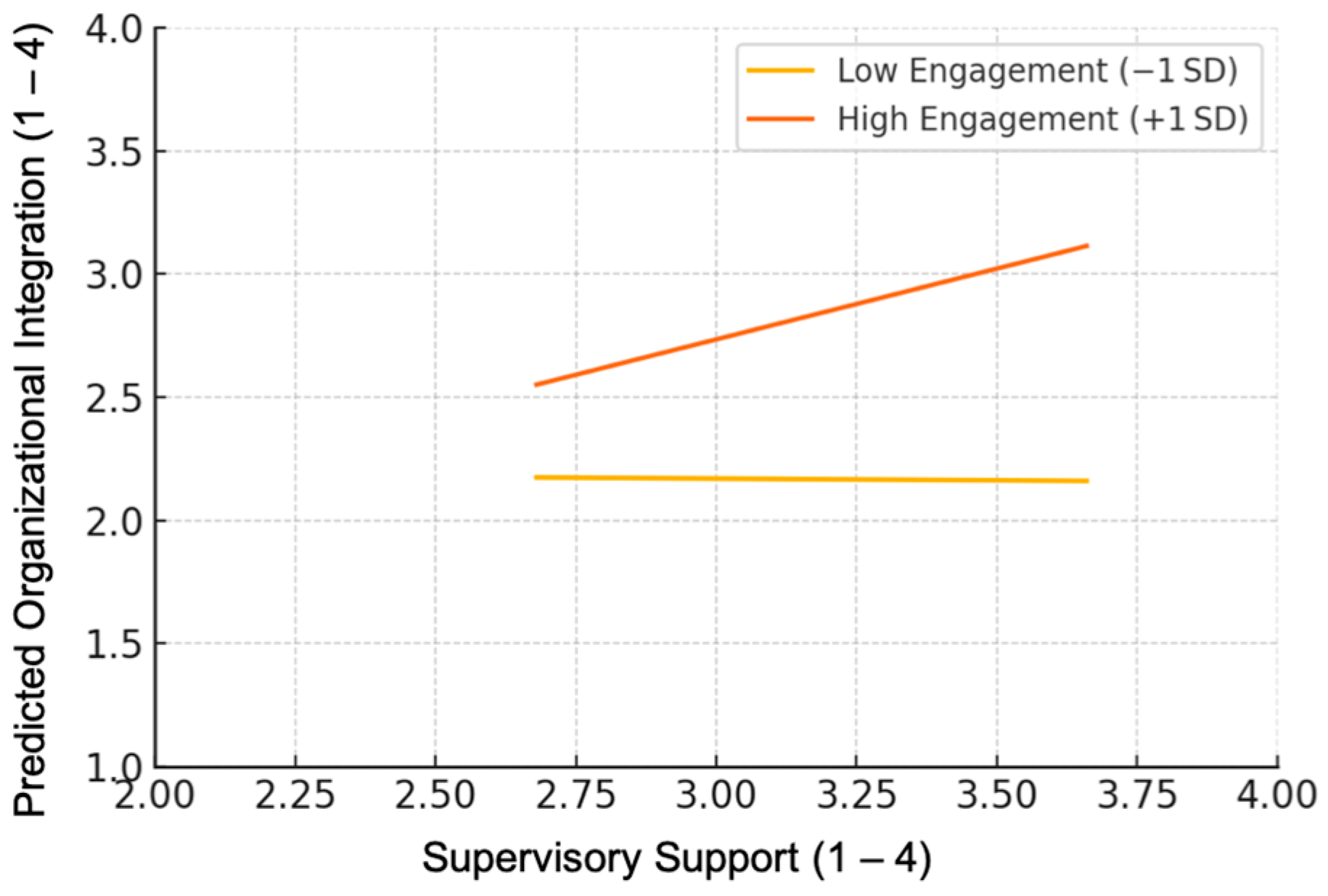

4.3. Moderating Role of Work Engagement on the Supervisory Support–Integration Relationship

5. Discussion

5.1. Limitations

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Organizational Climate Items

Appendix B. The Utrecht Work Engagement Scale

References

- Abdelwahed, N. A. A., & Doghan, M. A. A. (2023). Developing employee productivity and performance through workengagement and organizational factors in an educational society. Societies, 13, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abelson, R. P. (1985). A variance explanation paradox: When a little is a lot. Psychological Bulletin, 97(1), 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abun, D., Menor, R. I., Catabagan, N. C., Magallanes, T., & Ranay, F. B. (2021). Organizational climate and work engagement of employees of divine word colleges in Ilocos Region, Philippines. International Journal of Research in Business and Social Science (2147–4478), 10(1), 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adinew, Y. (2024). A comparative study on motivational strategies, organizational culture, and climate in public and private institutions. Current Psychology, 43(13), 11470–11492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, H., Beaty, J. C., Boik, R. J., & Pierce, C. A. (2005). Effect size and power in assessingmoderating effects of categorical variables using multiple regression. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(1), 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, H., & Vandenberg, R. J. (2014). An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure: Improving research quality before data collection. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1, 569–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, K. Z. B., Jasimuddin, S. M., & Kee, W. L. (2018). Organizational climate and job satisfaction: Do employees’ personalities matter? Management Decision, 56(2), 421–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht, S., Breidahl, E., & Marty, A. (2018). Organizational resources, organizational engagement climate, and employee engagement. Career Development International, 23(1), 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, S. L. (2014). A climate for engagement: Some theory, models, measures, research, and practical applications. In B. Schneider, & K. Barbera (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of organizational climate and culture (pp. 400–413). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ancarani, A., Mauro, C. D., & Giammanco, M. D. (2019). Linking organizational climate to work engagement: A study in the healthcare sector. International Journal of Public Administration, 42(7), 547–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, M., Moen, O., & Brett, P. O. (2020). The organizational climate for psychological safety: Associations with SMEs’ innovation capabilities and innovation performance. Journal of Engineering and Technology Management, 55, 101554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonakis, J., Bendahan, S., Jacquart, P., & Lalive, R. (2010). On making causal claims: A review and recommendtions. The Leadership Quarterly, 21(6), 1086–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The job demands–resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22(3), 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2017). Job demands–resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberger, P. A. (2019). On the replicability of abductive research in management and organizations: Internal repliction and its alternatives. Academy of Management Discoveries, 5(2), 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batlis, N. C. (1980). The effect of organizational climate on job satisfaction, anxiety, and propensity to leave. The Journal of Psychology, 104(3–4), 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berberoglu, A. (2018). Impact of organizational climate on organizational commitment and perceived organizational performance: Empirical evidence from public hospitals. BMC Health Services Research, 18, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bliese, P. D. (2000). Within-group agreement, non-independence, and reliability: Implications for data aggregation and analyses. In K. J. Klein, & S. W. J. Kozlowski (Eds.), Multilevel theory, research, and methods in organizations (pp. 349–381). Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Bos-Nehles, A. C., & Veenendaal, A. A. (2019). Perceptions of HR practices and innovative work behavior: The moderating effect of an innovative climate. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 30(18), 2661–2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breevaart, K., Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Hetland, J. (2014). The measurement of state work engagement: A multilevel factor analytic study. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 30(4), 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M., Wang, M., & Cheng, J. (2024). The effect of servant leadership on work engagement: The role of employee resilience and organizational support. Behavioral Sciences, 14, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, M. S., Bradley, J. C., Wallace, J. C., & Burke, M. J. (2009). Workplace safety: A meta-analysis of the roles of person and situation factors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(5), 1103–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CIPD. (2022). Employee engagement & motivation–factsheet. Available online: https://www.cipd.co.uk/knowledge/fundamentals/relations/engagement/factsheet#gref (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Clement, O. I., & Eketu, C. A. (2019). Organizational climate and employee engagement in banks in rivers state, Nigeria. International Journal of Advanced Academic Research, 5(3), 57–84. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S. G., & Aiken, L. S. (2013). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Colquitt, J. A., Scott, B. A., Rodell, J. B., Long, D. M., Zapata, C. P., Conlon, D. E., & Wesson, M. J. (2013). Justice at the millennium, a decade later: A meta-analytic test of social exchange and affect-based perspectives. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98(2), 199–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, J. M., & Lance, C. E. (2010). What reviewers should expect from authors regarding common method bias in organizational research. Journal of Business and Psychology, 25(3), 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, E. R., LePine, J. A., & Rich, B. L. (2010). Linking job demands and resources to employee engagement and burnout: A theoretical extension and meta-analytic test. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(5), 834–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E., & Bakker, A. B. (2023). Job demands-resources theory in times of crises: Newpropositions. Organizational Psychology Review, 13(3), 209–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etikan, I., Musa, S. A., & Alkassim, R. S. (2016). Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics, 5(1), 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, C. M., Simmering, M. J., Atinc, G., Atinc, Y., & Babin, B. J. (2016). Common methods variance detection in business research. Organizational Research Methods, 19(3), 473–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funder, D. C., & Ozer, D. J. (2019). Evaluating effect size in psychological research: Sense and nonsense. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science, 2(2), 156–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gignac, G. E., & Szodorai, E. T. (2016). Effect size guidelines for individual differences researchers. Personality and Individual Differences, 102, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J., Jr., Page, M., & Brunsveld, N. (2019). Essentials of business research methods. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Sarstedt, M., Matthews, L. M., & Ringle, C. M. (2016). Identifying and treating unobserved heterogeneity with FIMIX-PLS: Part I–method. European Business Review, 28(1), 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakanen, J. J., Bakker, A. B., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2006). Burnout and work engagement among teachers. Journal of School Psychology, 43(6), 495–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbesleben, J. R. B. (2010). A meta-analysis of work engagement: Relationships with burnout, demands, resources, and consequences. In A. B. Bakker, & M. P. Leiter (Eds.), Work engagement: A handbook of essential theory and research (pp. 102–117). Psychology Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haryono, S., Ambarwati, Y. I., & Saad, M. S. M. (2019). Do organizational climate and organizational justice enhance job performance through job satisfaction? A study of Indonesian employees. Academy of Strategic Management Journal, 18(1), 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Hayat, A., & Afshari, L. (2021). Supportive organizational climate: A moderated mediation model of workplace bullying and employee well-being. Personnel Review, 50(7/8), 1685–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idris, M. A., Dollard, M. F., & Tuckey, M. R. (2015). Psychosocial safety climate as a management tool for employee engagement and performance: A multilevel analysis. International Journal of Stress Management, 22(2), 183–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, L. R., Choi, C. C., Ko, C. E., McNeil, P. K., Minton, M. K., Wright, M. A., & Kim, K. (2008). Organizational and psychological climate: A review of theory and research. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 17(1), 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, L. R., Demaree, R. G., & Wolf, G. (1984). Estimating within-group interrater reliability with and without response bias. Journal of Applied Psychology, 69(1), 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jex, S. M., Sliter, M. T., & Britton, A. (2014). Employee stress and well-being. In B. Schneider, & K. M. Barbera (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of organizational climate and culture (pp. 177–196). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, M. H., & McDonald, B. (2017). Understanding employee engagement in the public sector: The role of immediate supervisor, perceived organizational support, and learning opportunities. The American Review of Public Administration, 47(8), 881–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joel, O. O., Moses, C. L., Igbinoba, E. E., Olokundun, M. A., Salau, O. P., Ojebola, O., & Adebayo, O. P. (2023). Bolstering the moderating effect of supervisory innovative support on organisational learning and employees’ engagement. Administrative Sciences, 13, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, W. A. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Academy of Management Journal, 33(4), 692–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H. J. A., & Busser, J. A. (2018). Impact of service climate and psychological capital on employee engagement: The role of organizational hierarchy. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 75, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsaros, K. K. (2025a). Employee change participation during the COVID-19 pandemic: The role of inclusive leadership, trust in leadership, and bottom-up learning. Journal of General Management, 03063070251341000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsaros, K. K. (2025b). Remote employee work performance in the meta COVID-19 era: Evidence from Greece. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 74(1), 340–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawiana, I., Dewi, L. K. C., Hartati, P. S., Setini, M., & Asih, D. (2021). Effects of leadership and psychological climate on organizational commitment in the digitization era. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business, 8(1), 1051–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, N., Koc, E., & Topcu, D. (2010). An exploratory analysis of the influence of human resource management activities and organizational climate on job satisfaction in Turkish banks. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 21(11), 2031–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köse, A. (2016). The relationship between work engagement behavior and perceived organizational support and organizational climate. Journal of Education and Practice, 7(27), 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuenzi, M., Mayer, D. M., & Greenbaum, R. L. (2020). Creating an ethical organizational environment: The relationship between ethical leadership, ethical organizational climate, and unethical behavior. Personnel Psychology, 73(1), 43–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumprang, K., & Suriyankietkaew, S. (2024). Mechanisms of organizational mindfulness on employee well-being and engagement: A multi-level analysis. Administrative Sciences, 14, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, K., & Kim, T. (2020). An integrative literature review of employee engagement and innovative behavior: Revisiting the JD–R model. Human Resource Management Review, 30(2), 100704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maamari, B. E., & Majdalani, J. F. (2017). Emotional intelligence, leadership style and organizational climate. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 25(2), 327–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macey, W. H., & Schneider, B. (2008). The meaning of employee engagement. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 1(1), 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macey, W. H., Schneider, B., Barbera, K. M., & Young, S. A. (2009). Employee engagement: Tools for analysis, practice, and competitive advantage. Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClelland, G. H., & Judd, C. M. (1993). Statistical difficulties of detecting interactions and moderator effects. Psychological Bulletin, 114(2), 376–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menguc, B., Auh, S., Yeniaras, V., & Katsikeas, C. S. (2017). The role of climate: Implications for service employee engagement and customer service performance. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45, 428–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mone, E. M., & London, M. (2014). Employee engagement through effective performance management: A practical guide for managers. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moslehpour, M., Altantsetseg, P., Mou, W., & Wong, W. K. (2018). Organizational climate and work style: The missing links for sustainability of leadership and satisfied employees. Sustainability, 11(1), 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullins, L. J. (2016). Management and organisational behaviour (11th ed.). Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Nabella, S. D., Rivaldo, Y., Kurniawan, R., Nurmayunita, N., Sari, D. P., Luran, M. F., & Wulandari, K. (2022). The influence of leadership and organizational culture mediated by organizational climate on governance at senior high school in Batam City. Journal of Educational and Social Research, 12(5), 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahrgang, J. D., Morgeson, F. P., & Hofmann, D. A. (2011). Safety at work: A meta-analytic investigation of the link between job demands, job resources, burnout, engagement, and safety outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(1), 71–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman, A., Round, H., Wang, S., & Mount, M. (2020). Innovation climate: A systematic review of the literature and agenda for future research. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 93(1), 73–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeng, H. A., Arhinful, R., Mensah, L., & Owusu-Sarfo, J. S. (2024). Assessing the influence of the knowledge management cycle on job satisfaction and organizational culture considering the interplay of employee engagement. Sustainability, 16, 8728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, R. M. (2007). A caution regarding rules of thumb for variance inflation factors. Quality & Quantity: International Journal of Methodology, 41(5), 673–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostroff, C., Kinicki, A. J., & Tamkins, M. M. (2003). Organizational culture and climate. In W. C. Borman, D. R. Ilgen, & R. J. Klimoski (Eds.), Handbook of psychology: Industrial and organizational psychology (Vol. 12, pp. 565–593). Wiley. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S. K., Bindl, U. K., & Strauss, K. (2010). Making things happen: A model of proactive motivation. Journal of Management, 36(4), 827–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, M., West, M. A., Shackleton, V. J., Dawson, J. F., Lawthom, R., Maitlis, S., Robinson, D. L., & Wallace, A. M. (2005). Validating the organizational climate measure: Links to managerial practices, productivity and innovation. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26(4), 379–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, G. (2017). Structuring leadership and team creativity: The mediating role of team innovation climate. Social Behavior and Personality, 45, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, D. K., Mangipudi, D. M. R., Vaidya, D. R., & Muralidhar, B. (2020). Organizational climate, opportunities, challenges and psychological wellbeing of the remote working employees during COVID-19 pandemic: A general linear model approach with reference to information technology industry in Hyderabad. International Journal of Advanced Research in Engineering and Technology (IJARET), 11(4), 409–426. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K. J., Curran, P. J., & Bauer, D. J. (2006). Computational tools for probing interactions in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 31(4), 437–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, R. D., & Karasick, B. W. (1973). The effects of organizational climate on managerial job performance and job satisfaction. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 9(1), 126–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasool, S. F., Wang, M., Tang, M., Saeed, A., & Iqbal, J. (2021). How toxic workplace environment effects the employee engagement: The mediating role of organizational support and employee wellbeing. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(5), 2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhoades, L., & Eisenberger, R. (2002). Perceived organizational support: A review of the literature. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(4), 698–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saks, A. M. (2019). Antecedents and consequences of employee engagement revisited. Journal of Organizational Effectiveness: People and Performance, 6(1), 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saks, A. M., & Gruman, J. A. (2014). What do we really know about employee engagement? Human Resource Development Quarterly, 25(2), 155–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B. (2016). Heavy work investment, personality and organizational climate. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 31(6), 1057–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B., & Bakker, A. B. (2004). Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25(3), 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B., & Van Rhenen, W. (2009). How changes in job demands and resources predict burnout, work engagement, and sickness absenteeism. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 30(7), 893–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B., Salanova, M., González-Romá, V., & Bakker, A. B. (2002). The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. Journal of Happiness Studies, 3(1), 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, B., Ehrhart, M. G., & Macey, W. H. (2013). Organizational climate and culture. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 361–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, B., González-Romá, V., Ostroff, C., & West, M. A. (2017). Organizational climate and culture: Reflections on the history of the constructs in the Journal of Applied Psychology. Journal of Applied Psychology, 102(3), 468–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, B., & Reichers, A. E. (1983). On the etiology of climates. Personnel Psychology, 36(1), 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwatka, N. V., Sinclair, R. R., Fan, W., Dally, M., Shore, E., Brown, C. E., Tenney, L., & Newman, L. S. (2020). How does organizational climate motivate employee safe and healthy behavior in small business?: A self-determination theory perspective. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 62(5), 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schyns, B., Van Veldhoven, M., & Wood, S. (2009). Organizational climate, relative psychological climate and job satisfaction: The example of supportive leadership climate. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 30(7), 649–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadish, W. R., Cook, T. D., & Campbell, D. T. (2002). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference. Houghton Mifflin. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S. (2017). Organizational climate as a predictor to employees’ behavior. In Strategic human capital development and management in emerging economies (pp. 20–40). IGI Global Scientific Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singha, S. (2024). Nurturing positive organizational climates to enhance work success: A positive psychology approach. In Fostering organizational sustainability with positive psychology (pp. 84–107). IGI Global. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W., Wang, G. Z., & Ma, X. (2020). Environmental innovation practices and green product innovation performance: A perspective from organizational climate. Sustainable Development, 28(1), 224–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, P. E. (2006). Method variance in organizational research: Truth or urban legend? Organizational Research Methods, 9(2), 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, P. E. (2019). Do not cross me: Optimizing the use of cross-sectional designs. Journal of Business and Psychology, 34(2), 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinkner, R., Tyler, T. R., & Goff, P. A. (2016). Justice from within: The relations between a procedurally just organizational climate and police organizational efficiency, endorsement of democratic policing, and officer well-being. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 22(2), 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viitala, R., Tanskanen, J., & Säntti, R. (2015). The connection between organizational climate and well-being at work. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 23(4), 606–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardono, G., Moeins, A., & Sunaryo, W. (2022). Influence of organizational climate on OCB and employee engagement. Journal of World Science, 1(8), 560–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, M. A., Topakas, A., & Dawson, J. F. (2014). Climate and culture for healthcare performance. In B. Schneider, & K. Barbera (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of organizational climate and culture. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulou, D., Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2007). The role of personal resources in the Job Demands–Resources model. International Journal of Stress Management, 14(2), 121–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulou, D., Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2009). Reciprocal relationships between job resources, personal resources, and work engagement. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 74(3), 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zohar, D. (2014). Safety climate. In B. Schneider, & K. Barbera (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of organizational climate and culture. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study/Context | Climate Facets | Engagement Measure | Level of Analysis | Method | Key Finding | Relevance to Gap |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clement and Eketu (2019), Nigerian banking | Fairness, autonomy, recognition (supportive climate) | Employee engagement | Individual | Regression | Supportive climate → higher engagement | Service/finance; not industrial |

| Abun et al. (2021), HEIs (Philippines) | Clarity, recognition (supportive climate) | Engagement (cognitive/emotional/physical) | Individual | Regression | Positive climate → higher engagement | Education sector |

| Ancarani et al. (2019), Healthcare | Organizational climate | Engagement | Individual | Regression/SEM | Positive climate → higher engagement | Healthcare sector |

| Wardono et al. (2022), Mixed sectors | Supportive climate | Engagement & OCB | Individual | Survey models | Supportive climate boosts engagement/OCB | Broader sectors |

| Rasool et al. (2021), Mixed | Toxic climate | Engagement | Individual | SEM | Toxic climate suppresses engagement | Demonstrates sensitivity |

| Current study, Greek industrial manufacturing | Welfare, supervisory support, integration (OCM facets) | UWES-17 | Individual (psychological climate) | Correlations, regression, moderation | Small but significant associations; engagement moderates support → integration | Under-researched sector; facet comparison & moderation |

| Variable | M (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Work engagement | 3.90 (0.95) | — | 0.160 * | 0.258 ** | 0.222 ** |

| 2. OC Integration | 2.85 (0.50) | 0.160 * | — | 0.433 ** | 0.156 |

| 3. OC Welfare | 3.03 (0.56) | 0.258 ** | 0.433 ** | — | 0.418 ** |

| 4. OC Supervisory Support | 3.17 (0.49) | 0.222 ** | 0.156 | 0.418 ** | — |

| Predictor | B | SE B | β | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 1.83 | 0.60 | — | 3.03 | 0.003 |

| OC Integration | 0.12 | 0.17 | 0.07 | 0.74 | 0.462 |

| OC Welfare | 0.29 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 1.80 | 0.075 |

| OC Supervisory Support | 0.27 | 0.17 | 0.14 | 1.62 | 0.107 |

| Predictor | B | SE B | β | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | |||||

| Constant | 2.50 | 0.45 | — | 5.56 | 0.000 |

| Supervisory Support | 0.28 | 0.12 | 0.19 | 2.34 | 0.021 |

| Work engagement | 0.35 | 0.12 | 0.24 | 2.79 | 0.006 |

| Step 2 | |||||

| Interaction: Support × Work engagement | 0.31 | 0.15 | 0.18 | 2.06 | 0.041 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tsoni, E.; Lazanaki, V.; Katsaros, K. The Influence of Organizational Climate on Work Engagement: Evidence from the Greek Industrial Sector. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 413. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15110413

Tsoni E, Lazanaki V, Katsaros K. The Influence of Organizational Climate on Work Engagement: Evidence from the Greek Industrial Sector. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(11):413. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15110413

Chicago/Turabian StyleTsoni, Evdokia, Vera Lazanaki, and Kleanthis Katsaros. 2025. "The Influence of Organizational Climate on Work Engagement: Evidence from the Greek Industrial Sector" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 11: 413. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15110413

APA StyleTsoni, E., Lazanaki, V., & Katsaros, K. (2025). The Influence of Organizational Climate on Work Engagement: Evidence from the Greek Industrial Sector. Administrative Sciences, 15(11), 413. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15110413