Employee Profiles of Remote Work Benefits and the Role of Leadership in a Medium-Sized Italian IT Company

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. What Is Sustainability?

2.2. Sustainability and Remote Work

2.3. Attitudes Toward Remote Work

2.4. Leadership, Sustainability and Remote Work

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Procedure

3.2. Participants

3.3. Measures

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

Latent Classes Based on Remote Working Benefits

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Practical Implications

6.2. Limits

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdulrahim, H. (2024). Remote working and sustainability: A bibliometric mapping analysis. Journal of Ecohumanism, 3(3), 2076–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B. E., Kreiner, G. E., & Fugate, M. (2000). All in a day’s work: Boundaries and micro role transitions. The Academy of Management Review, 25(3), 472–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakaç, C., Zyberaj, J., & Barela, J. C. (2023). Predicting employee telecommuting preferences and job outcomes amid COVID-19 pandemic: A latent profile analysis. Current Psychology, 42, 8680–8695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barhate, B., & Dirani, K. M. (2021). Career aspirations of generation Z: A systematic literature review. European Journal of Training and Development, 46(1/2), 139–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, T. N., & Erdogan, B. (2015). The Oxford handbook of leader-member exchange. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Boeske, J. (2023). Leadership towards sustainability: A review of sustainable, sustainability, and environmental leadership. Sustainability, 15(16), 12626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeske, J., & Murray, P. A. (2022). The intellectual domains of sustainability leadership in SMEs. Sustainability, 14(4), 1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputo, A., Toscano, F., Dolce, V., & De Angelis, M. (2024). Leadership in face-to-face and virtual teams: A systematic literature review on hybrid teams management. Informing Science: The International Journal of an Emerging Transdiscipline, 27, 008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro, R., & Moreira, A. C. (2024). Unveiling paradoxes: Navigating SMEs readiness in the post-pandemic normality. Cogent Business & Management, 11(1), 2330114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y., Chien, C., & Shen, L. F. (2023). Teleworking during the COVID-19 pandemic: A leader-member exchange perspective. In Evidence-based HRM: A global forum for empirical scholarship (Vol. 11, No. 1, pp. 68–84). Emerald Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coca, L. C. M., & Pîslaru, M. (2024). Definition of sustainability—Bibliometric analysis of the most highlighted papers. Proceedings of the International Conference on Business Excellence, 18(1), 888–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colak, M., & Saridogan, B. C. (2023). Exploring the remote work revolution: A managerial view of the tech sector’s response to the new normal. International Journal of Contemporary Management, 59(4), 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, F., Baykal, E., & Abid, G. (2020). E-leadership and teleworking in times of COVID-19 and beyond: What we know and where do we go. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 590271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSanctis, G. (1984). Attitudes toward telecommuting: Implications for work-at-home programs. Information & Management, 7(3), 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fabio, A. (2017). The psychology of sustainability and sustainable development for well-being in organizations. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolce, V., Ghislieri, C., Molino, M., & Vayre, É. (2024). “A good night’s sleep!” How do remote workers juggle work and family during lockdown? Some answers from a French mixed-methods study. Current Psychology: A Journal for Diverse Perspectives on Diverse Psychological Issues, 43(30), 24915–24929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebner, C., Brandstätter, P. H., & Schmidthaler, M. (2021, June 18–20). Key factors influencing demand for remote work among employees: Empirical evidence from Austria during the COVID-19 pandemic [Conference paper]. 18th KIRC Conference, Krems, Austria. Available online: https://pure.fh-ooe.at/en/publications/key-factors-influencing-demand-for-remote-work-among-employees-am (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. (1994). Towards the sustainable corporation: Win-win-win business strategies for sustainable development. California Management Review, 36(2), 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elldér, E. (2020). Telework and daily travel: New evidence from Sweden. Journal of Transport Geography, 86, 102777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emas, R. (2015). The concept of sustainable development: Definition and defining principles (Brief for GSDR 2015). Florida International University. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/sites/default/files/documents/5839GSDR%202015_SD_concept_definiton_rev.pdf (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Epstein, M. J. (2008). Making sustainability work: Best practices in managing and measuring corporate social, environmental and economic impacts (1st ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurosif. (2025, August 14). Investor and business joint statement on Omnibus initiative. Available online: https://www.eurosif.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Joint-statement-Omnibus.pdf (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Eustachio, J. H. P. P., Caldana, A. C. F., & Leal Filho, W. (2023). Sustainability leadership: Conceptual foundations and research landscape. Journal of Cleaner Production, 415, 137761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fodor, M., & Jaeckel, K. (2018). What does it take to have a successful career through the eyes of generation Z: Based on the results of a primary qualitative research. International Journal on Lifelong Education and Leadership, 4(1), 1–7. Available online: https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/ijlel/issue/39629/468944 (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Gallup. (2023). Hybrid work. Available online: https://www.gallup.com/401384/indicator-hybrid-work.aspx (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- García-Sánchez, I.-M., Cunha-Araujo, D.-J., Amor-Esteban, V., & Enciso-Alfaro, S.-Y. (2024). Leadership and agenda 2030 in the context of big challenges: Sustainable development goals on the agenda of the most powerful CEOs. Administrative Sciences, 14(7), 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissdoerfer, M., Savaget, P., Bocken, N. M. P., & Hultink, E. J. (2017). The circular economy—A new sustainability paradigm? Journal of Cleaner Production, 143(6), 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghislieri, C., Molino, M., & Dolce, V. (2023). To work or not to work remotely? Work-to-family interface before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. La Medicina del Lavoro, 114(4), e2023027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, M., & Jena, L. K. (2024). Understanding leader–member exchange on job satisfaction: While work interfaces between home and life? In Evidence-based HRM: A global forum for empirical scholarship (Vol. 12, No. 4, pp. 742–759). Emerald Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graen, G. B., & Uhl-Bien, M. (1995). Relationship-based approach to leadership: Development of leader-member exchange (LMX) theory of leadership over 25 years: Applying a multi-level multi-domain perspective. The Leadership Quarterly, 6(2), 219–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R., Kaur, H., & Bhat, D. A. R. (2025). Green human resource management, green organisational citizenship behaviour and organisational sustainability in the post-pandemic era: An ability, motivation, opportunity and resource-based view perspective. Business Strategy and Development, 8, e70126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallinger, P., & Suriyankietkaew, S. (2018). Science mapping of the knowledge base on sustainable leadership, 1990–2018. Sustainability, 10(12), 4846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellemans, C., & Vayre, É. (2022). “Spillover” work via technology: Organizational antecedents and health impacts. In Digitalization of work: New spaces and new working times (Vol. 5, pp. 1–23). Wiley. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, J., & Bardoel, A. (2023). The future is hybrid: How organisations are designing and supporting sustainable hybrid work models in post-pandemic Australia. Sustainability, 15(4), 3086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingusci, E., Signore, F., Cortese, C. G., Molino, M., & Pasca, P. (2023). Development and validation of the remote working benefits & disadvantages scale. Quality & Quantity, 57, 1159–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Istat. (2024a). Decennio digitale e capitale umano: Il ritardo dell’Italia nelle competenze. Istituto Nazionale di Statistica. Available online: https://www.istat.it/it/files/2024/06/STATISTICA_TODAY_ICT_2023.pdf (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Istat. (2024b). Structural business statistics: Enterprises and enterprise groupsyear 2022. Available online: https://www.istat.it/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/EN-SBS-enterprise-enterprise-groups-2022.pdf (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Kemp, R., & Martens, P. (2007). Sustainable development: How to manage something that is subjective and never can be achieved? Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy, 3(1), 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J., & Dirks, A. (2023). Is your organization’s remote work strategy “working”? Exploring the impact of employees’ attitudes toward flexible work arrangements on inclusion and turnover intention. Therapeutic Innovation & Regulatory Science, 57, 1209–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, B., & Paterson, F. (2018). Behavioural competencies of sustainability leaders: An empirical investigation. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 31(3), 557–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreiner, G. E., Hollensbe, E. C., & Sheep, M. L. (2009). Balancing borders and bridges: Negotiating the work-home interface via boundary work tactics. Academy of Management Journal, 52(4), 704–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhlman, T., & Farrington, J. (2010). What is sustainability? Sustainability, 2(11), 3436–3448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, A., & Singh, M. P. (2023). A journey of social sustainability in organization during MDG & SDG period: A bibliometric analysis. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences, 88, 101668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laborie, C., Desmarais, C., Abord de Chatillon, E., Lacroux, A., & Jeoffrion, C. (2024). The benefits of an enabling managerial control style in a teleworking situation: A latent profile analysis. European Management Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lartey, F. (2022). Using EENDEED to measure remote employee engagement: Influence of the sense of belonging at work and the leader-member exchange (LMX) on virtual employee engagement. Journal of Human Resource and Sustainability, 10, 203–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littler. (2023, November). 2023 European employer survey report. Available online: https://www.littler.com/sites/default/files/2023_littler_european_employer_survey_report.pdf?lec6tn7bd (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Lozano, R. (2006). Incorporation and institutionalization of sustainable development into universities: Breaking through barriers to change. Journal of Cleaner Production, 14(9–11), 787–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez de Anguita, P., Alonso, E., & Martín, M. Á. (2008). Environmental economic, political and ethical integration in a common decision-making framework. Journal of Environmental Management, 88(1), 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moglia, M., Hopkins, J., & Bardoel, A. (2021). Telework, hybrid work and the United Nation’s sustainable development goals: Towards policy coherence. Sustainability, 13(16), 9222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molino, M., Cortese, C. G., & Ghislieri, C. (2019). Unsustainable working conditions: The association of destructive leadership, use of technology, and workload with workaholism and exhaustion. Sustainability, 11(2), 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Council of University Research Administrators. (2021). Remote work survey. Available online: https://www.ncura.edu/Portals/0/Docs/RemoteWorkSurvey.pdf (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Nedelko, Z., & Potocan, V. (2021). Sustainability of organizations: The contribution of personal values to democratic leadership behavior focused on the sustainability of organizations. Sustainability, 13(8), 4207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, E. S. W., Schweitzer, L., & Lyons, S. T. (2010). New generation, great expectations: A field study of the millennial generation. Journal of Business and Psychology, 25(2), 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2024). Empowering SMEs for digital transformation and innovation: The Italian way. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/blogs/2024/06/empowering-smes-for-digital-transformation-and-innovation-the-italian-way.html (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Olawumi, T. O., & Chan, D. W. M. (2018). A scientometric review of global research on sustainability and sustainable development. Journal of Cleaner Production, 183, 231–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orzeł, B., & Wolniak, R. (2022). Digitization in the design and construction industry—Remote work in the context of sustainability: A study from Poland. Sustainability, 14(3), 1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxford English Dictionary. (2022). Available online: www.oed.com/view/Entry/299890 (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Palumbo, R. (2020). Let me go to the office! An investigation into the side effects of working from home on work-life balance. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 33(6/7), 771–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrilli, S., Giunchi, M., & Vonthron, A. M. (2024). Leader–member exchange (LMX) and adjustment to the work mode as protective factors to counteract exhaustion and turnover intention: A chain mediation model. Sustainability, 16(23), 10254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramcilovic-Suominen, S., & Pülzl, H. (2018). Sustainable development—A ‘selling point’ of the emerging EU bioeconomy policy framework? Journal of Cleaner Production, 172, 4170–4180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rampasso, I. S., Santana, M., Serafim, M. P., Dibbern, T., Rodrigues, E. A., Filho, W. L., & Anholon, R. (2022). Trends in remote work: A science mapping study. Work, 71(2), 441–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redclift, M. (2005). Sustainable development (1987–2005): An oxymoron comes of age. Sustainable Development, 13(4), 212–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuters. (2025, June 30). Businesses urge EU not to weaken sustainability rules. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/sustainability/boards-policy-regulation/businesses-urge-eu-not-weaken-sustainability-rules-2025-06-30/ (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Richardson, G. R. A., & Lynes, J. K. (2007). Institutional motivations and barriers to the construction of green buildings on campus: A case study of the University of Waterloo, Ontario. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 8(4), 339–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos Villacorta, M. A., Ramos Farroñán, E. V., Alarcón García, R. E., Castro Ijiri, G. L., Bravo-Jaico, J. L., Minchola Vásquez, A. M., Ganoza-Ubillús, L. M., Escobedo Gálvez, J. F., Ríos Yovera, V. R., & Durand Gonzales, E. J. (2025). Telework for a sustainable future: Systematic review of its contribution to global corporate sustainability (2020–2024). Sustainability, 17(13), 5737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberto, R., Penna, M., Felici, B., & Rao, M. (2023). Smart working and flexible work arrangements: Opportunities and risks for sustainable communities. In P. Droege (Ed.), Intelligent environments (2nd ed., pp. 243–283). North-Holland. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, D. M., & Fried, Y. (2001). Editorial: Location, location, location: Contextualizing organizational research. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 22(1), 1–13. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3649603 (accessed on 16 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Ruggerio, C. A. (2021). Sustainability and sustainable development: A review of principles and definitions. The Science of the Total Environment, 786, 147481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbatini, A. (2023). Esperienze di misurazione del lavoro da remoto in Istat: Lessico, prospettive, finalità. INAPP. Available online: https://oa.inapp.gov.it/server/api/core/bitstreams/640b818c-acdf-4b05-b3d6-46e9ff81487d/content (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Sacchi, A., Ghislieri, C., Castellano, A., & Molino, M. (in press). Organizational culture and leadership for sustainability from a work and organizational psychology perspective. Rivista di Studi sulla Sostenibilità.

- Sachs, W. (1999). Sustainable development and the crisis of nature: On the political anatomy of an oxymoron. In F. Fischer (Ed.), Living with nature: Environmental politics as cultural discourse (pp. 23–41). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sartori, S., Latrônico, F., & Campos, L. M. S. (2014). Sustainability and sustainable development: A taxonomy in the field of literature. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 16(5), 847–870. [Google Scholar]

- Schreier, C., Udomkit, N., Kreis, J., & Setthakorn, K. (2024). Were relationships in the workplace changed? An exploration of the impacts of the mandatory work from home policy on small and medium-sized family businesses in Switzerland. ABAC Journal, 44(1), 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seol, H. (2022). snowLatent: Latent class analysis for jamovi [jamovi module]. GitHub. Available online: https://github.com/hyunsooseol/snowLatent (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Sinclair, R. R., Allen, T., Barber, L., Bergman, M., Britt, T., Butler, A., Ford, M., Hammer, L., Kath, L., Probst, T., & Yuan, Z. (2020). Occupational health science in the time of COVID-19: Now more than ever. Occupational Health Science, 4(1–2), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sostero, M., Bisello, M., & Fernández-Macías, E. (2024). Telework by region and the impact of COVID-19 pandemic: An occupational analysis (JRC Working Papers on Labour, Education and Technology 2024/02, JRC137946). European Commission. Available online: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC137946 (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Spagnoli, P., Manuti, A., Buono, C., & Ghislieri, C. (2021). The good, the bad and the blend: The strategic role of the “middle leadership” in work-family/life dynamics during remote working. Behavioral Sciences, 11(8), 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spagnoli, P., Molino, M., Molinaro, D., Giancaspro, M. L., Manuti, A., & Ghislieri, C. (2020). Workaholism and technostress during the COVID-19 emergency: The crucial role of the leaders on remote working. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 620310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaiser, V., Ranganathan, S., Swain, R. B., & Sumpter, D. J. T. (2017). The sustainable development oxymoron: Quantifying and modelling the incompatibility of sustainable development goals. International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology, 24(6), 457–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratone, M. E., Vătămănescu, E. M., Treapăt, L. M., Rusu, M., & Vidu, C. M. (2022). Contrasting traditional and virtual teams within the context of COVID-19 pandemic: From team culture towards objectives achievement. Sustainability, 14(8), 4558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susan, L., Anu, M., James, M., & Sven, S. (2020). What’s next for remote: An analysis of 2,000 tasks, 800 jobs, and nine countries. McKinsey Global Institute. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/future-of-work/whats-next-for-remote-work-an-analysis-of-2000-tasks-800-jobs-and-nine-countries (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Tenuta, P. (2009). Indici e modelli di sostenibilità. FrancoAngeli. [Google Scholar]

- The Jamovi Project. (2022). Jamovi (Version 2.3) [Computer software]. Available online: https://www.jamovi.org (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Toscano, F., & Zappalà, S. (2020a). Smart working in Italia: Origine, diffusione e possibili esiti. Psicologia Sociale, 2, 203–223. [Google Scholar]

- Toscano, F., & Zappalà, S. (2020b). Social isolation and stress as predictors of productivity perception and remote work satisfaction during the COVID-19 pandemic: The role of concern about the virus in a moderated double mediation. Sustainability, 12(23), 9804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tummers, L. G., & Bronkhorst, B. A. C. (2014). The impact of leader-member exchange (LMX) on work-family interference and work-family facilitation. Personnel Review, 43(4), 573–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. (2025). Sustainability disclosure by small and medium-sized enterprises in developing economies. Available online: https://unctad.org/publication/sustainability-disclosure-small-and-medium-sized-enterprises-developing-economies (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- United Nations General Assembly. (2025). Progress towards the sustainable development goals: Report of the secretary-general (A/80/81). Available online: https://docs.un.org/en/a/80/81 (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Varma, A., Jaiswal, A., Pereira, V., & Kumar, Y. L. N. (2022). Leader-member exchange in the age of remote work. Human Resource Development International, 25(2), 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtanen, M. (2020). The impact of remote working on employees’ work motivation & ability to work. Available online: https://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi:amk-2020111222696 (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Wang, B., Liu, Y., Qian, J., & Parker, S. K. (2021). Achieving effective remote working during the COVID-19 pandemic: A work design perspective. Applied Psychology, 70(1), 16–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WCED (World Commission on Environment and Development). (1987). Our common future. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, S. I., & Berntzen, M. N. (2019). Transformational leadership and leader–member exchange in distributed teams: The roles of electronic dependence and team task interdependence. Computers in Human Behavior, 92, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. (2013). World medical association declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA, 310(20), 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahari, A. I., Manan, D. I. A., Razali, F. M., Zolkaflil, S., & Said, J. (2024). Exploring the viability of remote work for SME. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 10(1), 100182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Remote Working Benefits |

|---|

| 1. Greater ability to better coordinate personal and work life and/or to adequately meet family needs |

| 2. Savings in time and/or money on commuting |

| 3. Reduced stress and/or more time available for oneself |

| 4. Ability to work autonomously and/or improved focus, organization and planning of one’s work |

| 5. Better relationships with colleagues and/or supervisors |

| 6. Increased job satisfaction |

| 7. Better use of available technology |

| Class | LL | AIC | CAIC | BIC | Entropy | df | G2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | −2404.03 | 4894.05 | 5106.02 | 5063.02 | 0.86 | 332 | 1311.07 |

| 3 | −2282.62 | 4695.25 | 5015.67 | 4950.67 | 0.86 | 310 | 1068.27 |

| 4 | −2232.75 | 4639.51 | 5068.38 | 4981.38 | 0.86 | 288 | 968.53 |

| 5 | −2194.38 | 4606.75 | 5144.08 | 5035.08 | 0.86 | 266 | 891.77 |

| 6 | −2177.02 | 4616.04 | 5261.82 | 5130.82 | 0.85 | 244 | 857.06 |

| Class | Parameters | LL | df | Deviance | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 43 | −2404.03 | - | - | - |

| 3 | 65 | −2282.62 | 22 | 242.8 | <0.001 |

| 4 | 87 | −2232.75 | 22 | 99.74 | <0.001 |

| 5 | 109 | −2194.38 | 22 | 76.76 | <0.001 |

| 6 | 131 | −2177.02 | 22 | 34.71 | 0.041 |

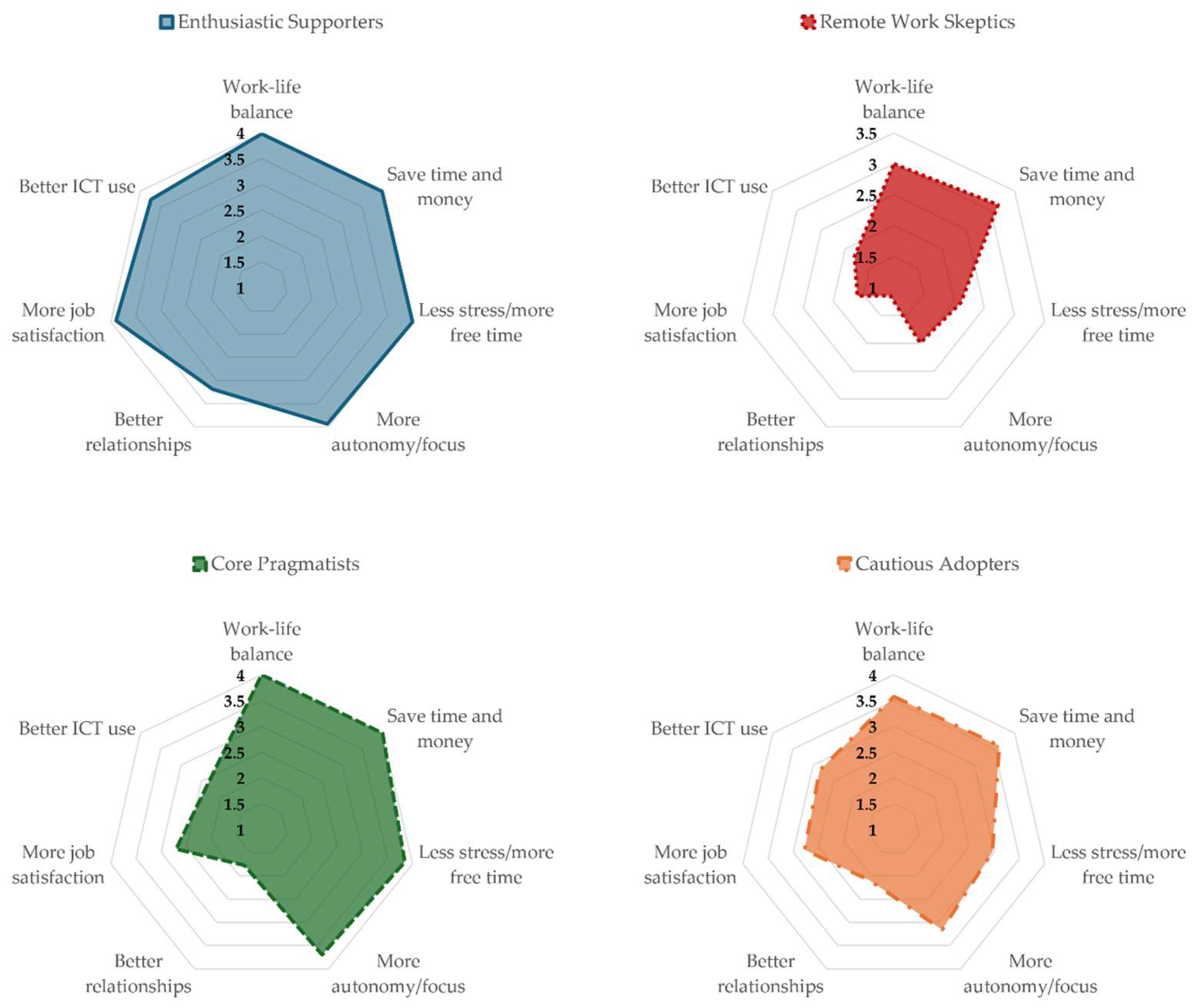

| Items | Classes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enthusiastic Supporters (37%) | Remote Work Skeptics (22%) | Core Pragmatists (17%) | Cautious Adopters (25%) | |

| 1. Work–life balance | 3.98 | 3.00 | 4.00 | 3.58 |

| 2. Save time and money | 3.99 | 3.15 | 4.00 | 3.61 |

| 3. Less stress/more free time | 4.00 | 2.11 | 3.85 | 2.96 |

| 4. More autonomy and focus | 3.94 | 1.99 | 3.70 | 3.16 |

| 5. Better relationships | 3.19 | 1.14 | 1.77 | 2.09 |

| 6. More job satisfaction | 3.89 | 1.60 | 2.70 | 2.77 |

| 7. Better ICT use | 3.74 | 1.81 | 2.36 | 2.84 |

| 1 vs. 2 | 1 vs. 3 | 1 vs. 4 | 2 vs. 3 | 2 vs. 4 | 3 vs. 4 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. (SE) | OR | Coef. (SE) | OR | Coef. (SE) | OR | Coef. (SE) | OR | Coef. (SE) | OR | Coef. (SE) | OR | |

| LMX | 0.18 (0.14) | 1.19 | −0.06 (0.16) | 0.94 | −0.18 (0.14) | 0.84 | −0.23 (0.17) | 0.79 | −0.35 (0.16) * | 0.70 | −0.12 (0.17) | 0.89 |

| Gender | 0.17 (0.33) | 1.18 | −0.35 (0.33) | 0.71 | −0.03 (0.31) | 0.97 | −0.52 (0.37) | 0.60 | −0.20 (0.35) | 0.82 | 0.32 (0.35) | 1.37 |

| Age | −0.21 (0.02) | 0.81 | −0.30 (0.16) | 0.74 | −0.36 (0.01) * | 0.70 | −0.08 (0.16) | 1.06 | −0.15 (0.16) | 0.86 | −0.06 (0.17) | 0.94 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sanseverino, D.; Sacchi, A.; Dolce, V.; Molino, M.; Ghislieri, C. Employee Profiles of Remote Work Benefits and the Role of Leadership in a Medium-Sized Italian IT Company. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 414. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15110414

Sanseverino D, Sacchi A, Dolce V, Molino M, Ghislieri C. Employee Profiles of Remote Work Benefits and the Role of Leadership in a Medium-Sized Italian IT Company. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(11):414. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15110414

Chicago/Turabian StyleSanseverino, Domenico, Alessandra Sacchi, Valentina Dolce, Monica Molino, and Chiara Ghislieri. 2025. "Employee Profiles of Remote Work Benefits and the Role of Leadership in a Medium-Sized Italian IT Company" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 11: 414. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15110414

APA StyleSanseverino, D., Sacchi, A., Dolce, V., Molino, M., & Ghislieri, C. (2025). Employee Profiles of Remote Work Benefits and the Role of Leadership in a Medium-Sized Italian IT Company. Administrative Sciences, 15(11), 414. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15110414