Abstract

This study investigates the impact of Machiavellian leadership on team creativity through the mediating role of cross-understanding and the moderating effect of task interdependence. While prior research has emphasized the negative consequences of Machiavellian tendencies, we argue that in highly interdependent team settings—such as project-based groups in technology, manufacturing, and financial enterprises—such leaders may foster constructive processes that enhance innovation. Drawing on social learning and trait activation theories, we conducted a multi-source survey of 86 teams (379 employees) in Chinese organizations. Team members assessed task interdependence and cross-understanding, while leaders reported their own Machiavellian tendencies and rated team creativity. Results show that Machiavellian leadership predicts team creativity indirectly through cross-understanding, with task interdependence strengthening this pathway. Theoretically, this study enriches leadership and creativity research by providing a nuanced view of how dark traits can stimulate team-level creativity through cognitive interaction mechanisms and by identifying task interdependence as a boundary condition. Practically, the findings suggest that organizations should recognize the creative potential of Machiavellian leaders in high-interdependence contexts, channel their ambition toward innovation goals, and design workflows that promote cross-understanding and collaboration.

1. Introduction

As organizations increasingly adopt teams as the basic unit of work, creativity research has shifted from the individual level to the team level (Biscaro & Montanari, 2025). Team leaders play a pivotal role in shaping team creativity. However, prior research has predominantly focused on positive leadership styles—such as transformational, authentic, ethical, and empowering leadership (Hughes et al., 2018; Mainemelis et al., 2015)—while devoting limited attention to the role of dark traits (Satornino et al., 2023). This oversight is problematic because dark traits are widespread among leaders, particularly successful ones (Neumann et al., 2020; Adam, 2019), and may shape team dynamics in important but overlooked ways. Within the Dark Triad (Paulhus & Williams, 2002), Machiavellianism refers to a stable personality trait that catches one’s inclination towards distrust others, look for control over others, look for self-status above all, and amoral manipulation (Dahling et al., 2009), is strongly associated with leadership motivation (Jones & Paulhus, 2009). There has been growing scholarly interest in Machiavellianism leadership (De Hoogh et al., 2021; Genau et al., 2022; Capezio et al., 2017), which is defined as a leadership strategy characterized by manipulation, cunning, and deliberate decision-making to achieve specific and desired goals (Dahling et al., 2009). Thus, while Machiavellianism denotes an internal disposition, Machiavellian leadership represents the outward expression of this disposition as interpreted through leader–follower interactions. Prior research has shown positive links between individuals’ Machiavellian traits and their creativity (Jonason et al., 2015), and Machiavellian leaders may, under certain conditions, foster employees’ creative performance (Faeq et al., 2024). However, to date, we lack a clear understanding of whether Machiavellian leaders—often adept at reading others and navigating complex social dynamics (Feng et al., 2022)—can transform these tendencies into constructive team processes that enhance team creativity. This gap is important because team creativity depends not only on members’ individual skills and ideas but also on their interaction and collaborative (Wang et al., 2025). By clarifying the conditions under which Machiavellian leadership can stimulate such processes, we can better understand how it may ultimately foster, rather than hinder, team creativity despite its dark reputation.

Scholars have found that social learning theory provides a suitable lens for examining how Machiavellian leaders navigate complex social interactions to influence subordinates (Drory & Gluskinos, 1980; Feng et al., 2022; Kiazad et al., 2010), for example by shaping followers’ moral disengagement and, ultimately, unethical behavior (Uppal & Bansal, 2023). However, far less attention has been given to team-level processes, even though they are critical because of their inherent complexity in team performance (Salas et al., 2008). To address this gap, this study introduces cross-understanding—an emergent team cognitive process that arising from members’ repeated interactions, communication, and efforts to understand one another’s knowledge and perspectives (Huber & Lewis, 2010)—as the key mechanism linking Machiavellian leadership to team creativity. At the same time, in line with social learning theory, leaders play a critical role in shaping this process (Bandura & Walters, 1977). Machiavellian leaders may recognize the importance of team unity and effort (Khan et al., 2023), and model sensitivity to others’ preferences and perspectives, articulating collective goals, and reinforcing collaborative behaviors to accelerate and guide the development of cross-understanding within the team. In this sense, cross-understanding reflects both a bottom-up emergent property of team dynamics and a top-down influence modeled by the leader, making it a particularly important mechanism for explaining how Machiavellian leadership may foster team creativity. Social learning theory posits that individuals acquire behaviors by observing others’ actions and their consequences (Bandura & Walters, 1977). Machiavellians are highly adaptable to situational demands (Genau et al., 2022), and they may adjust their behavior to align with environmental conditions in order to achieve their objectives. However, existing research has primarily focused on how organizational climates activate Machiavellian tendencies, with a lack attention on the role of task characteristics. Addressing this gap is critical, as task design constitutes a fundamental determinant of team interaction patterns and creative outcomes (Hoegl & Gemuenden, 2001). In this study, we introduce task interdependence as a boundary condition. Task interdependence—a core feature of work teams—refers to the degree to which members must exchange information, share resources, and collaborate to accomplish their tasks (Wageman, 1995). It not only directly shapes team processes (Wageman & Gordon, 2005) but also moderates the influence of other factors on these processes and outcomes (Ilgen et al., 2005). Although high-Machiavellian leaders often prioritize opportunism and personal gain over cooperation (Sakalaki et al., 2007), under conditions of high task interdependence, they may strategically downplay manipulative and exploitative behaviors and instead display cooperative and fair practices. Such adaptive behavior can build employee trust, foster collaboration, and ultimately enhance team creativity.

Accordingly, based on social learning theory and trait activation theory, we develop a theoretical model in which Machiavellian leadership affects team creativity through cross-understanding, with task interdependence serving as a moderator. This study makes the following contributions. First, while prior research on leadership and team creativity has primarily focused on constructive leadership traits, relatively little attention has been paid to dark traits. We extend this line of research by examining Machiavellianism—a dark trait closely tied to organizational and political contexts—thereby enriching our understanding of how leadership traits can foster team creativity. Second, existing studies on Machiavellian leadership have largely examined its effects on followers’ behaviors, often emphasizing negative outcomes, with limited attention to the team level mechanisms. By introducing cross-understanding, this study explores whether Machiavellian leadership can play a constructive role in fostering team creativity. In doing so, we extend the study of Machiavellian leadership from individual- and dyadic-level effects to team-level outcomes. Finally, while situational and organizational contexts are known to play an important role in shaping the behavioral choices of Machiavellian leaders (De Hoogh et al., 2021), the role of team task characteristics in the relationship between Machiavellian leadership and team outcomes has yet to be explored. By incorporating task interdependence as a moderator, this study not only verifies the situational dependence of Machiavellian leadership but also extends our understanding of its manifestations in meso-level contexts.

2. Theory Background and Hypothesis

2.1. Social Learning Theory and Trait Activation Theory

Social learning theory posits that individuals acquire behaviors by observing, modeling, and internalizing the actions of role models (Bandura & Walters, 1977; Bandura, 1986). By observing leaders, employees learn which behaviors are expected, rewarded or punished, and adjust their own behaviors accordingly. Drawing on social learning theory, we argue that Machiavellian leadership influences team creativity through cross-understanding. To manipulate effectively, Machiavellian leaders must accurately comprehend team members’ perspectives and intentions, thereby modeling such behaviors. Over time, this observational learning process encourages members to better attend to one another’s ideas, skills, and perspectives, fostering cross-understanding, and enabling the integration of diverse viewpoints that generate novel and useful ideas. Trait activation theory suggests that situations trigger personality traits, prompting trait-related behaviors (Tett et al., 2013). Although Machiavellians often seek to exploit others, they may comply with social norms and cooperate with organizations when it aligns with their self-interest (De Hoogh et al., 2021). Thus, the expression of Machiavellian traits is context-dependent (Greenbaum et al., 2017). This theory clarifies when Machiavellian leadership exerts positive effects. Under high task interdependence, leaders may strategically downplay manipulative tendencies and instead display cooperative behaviors. When members perceive a collaborative climate and observe leaders endorsing communication and mutual support, social learning is reinforced, cross-understanding is enhanced, and team creativity is more likely to emerge.

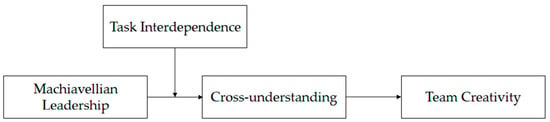

The study’s theoretical model is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Theoretical model of this study.

2.2. Machiavellian Leadership and Team Creativity

Research has shown that both exceptional creative achievements and everyday creative activities are often linked to unethical tendencies (Lebuda et al., 2021). Machiavellian leaders, who hold a competitive worldview (Khan et al., 2023), act as opportunists focused on personal gain (Gunnthorsdottir et al., 2002) and are driven by an obsessive pursuit of achievement and status (Dahling et al., 2009). Innovation, in turn, represents a powerful means of rapidly acquiring competitive advantages, power, and prestige (Jonason et al., 2015). Accordingly, in highly competitive business environments, Machiavellianism has been found to positively correlate with creative activities and innovation performance (Doornenbal et al., 2022; Lebuda et al., 2021). Given that leadership plays a crucial role in fostering team creativity (Al Harbi et al., 2019; Ribeiro et al., 2020), Machiavellian leadership may thus serve as an important antecedent of team creativity.

According to social learning theory, followers perceive team leaders as role models to identify which behaviors are recognized and valued within the team (Bai et al., 2019). First, when members observe their leader’s pursuit of innovation, they become more motivated to critically evaluate existing routines and assumptions without fear of reprisal. Consequently, employees are more willing to seek out and acquire additional knowledge, explore information from diverse sources, and integrate new perspectives into their thinking, and ultimately generating creative ideas. Second, Machiavellian leaders, with their strong goal orientation and willingness to employ unconventional or even unethical approaches to achieve objectives, can encourage members to break free from fixed thinking patterns, seek knowledge across domains, and experiment with new approaches. They may also provide the resources needed to explore and test these ideas. Such psychological support, resource provision, and implicit permission motivate members to achieve higher levels of creativity (Coutifaris & Grant, 2021). Finally, social learning theory highlights the role of reinforcement in shaping behavior. When members actively pursue innovation, Machiavellian leaders may adopt a charismatic style, offering encouragement, recognition, or rewards as a way to secure loyalty (Marbut et al., 2025). This positive reinforcement increases the likelihood that members will continue engaging in innovation-oriented behaviors.

Nevertheless, it is important to acknowledge that Machiavellian leaders are fundamentally motivated by self-interest (Gunnthorsdottir et al., 2002). When cooperation is not perceived as instrumental to their personal objectives, manipulative and exploitative tendencies may dominate, undermining trust and constraining team creativity (Kiazad et al., 2010). Thus, whether Machiavellian leaders foster or hinder creativity may depend on contextual factors that determine the extent to which constructive behaviors serve their self-interest.

Hypothesis 1.

Machiavellian leadership is positively related to team creativity.

2.3. The Mediating Role of Cross-Understanding

Cross-understanding is a key team cognitive process, referring to the extent to which team members accurately grasp one another’s knowledge base, thinking patterns, and cognitive frameworks. By understanding what others know, believe, prefer, and are sensitive to, team members can coordinate their actions more effectively and communicate ideas with greater efficiency (Janardhanan et al., 2020). While individual’s knowledge, skills, perspectives, and opinions provide the raw materials for creativity, cross-understanding is a crucial process that determines how these resources are transformed into team creativity (Meslec & Graff, 2015).

Drawing on social learning theory, we propose that Machiavellian leadership plays an important role in enhancing team cross-understanding. First, Machiavellian leaders are highly observant, they can put themselves in others’ positions to understand their intentions, perspectives, and knowledge (Keng-Highberger et al., 2024), while remaining highly attuned to subtle psychological preferences and shifts in members’ attitudes (Huber & Lewis, 2010). By observing and learning from such leaders, team members may become more inclined to understand what others know, believe, value, and are sensitive to, thereby deepening their grasp of one another’s mental models. Second, as typically goal-driven individuals, Machiavellian leaders establish clear goal orientations within the team. According to social learning theory, members tend to align with these orientations, and goal orientation—when shared at the team level—substantially promotes cross-understanding (Hirst et al., 2009; LePine, 2005). Finally, Machiavellian leaders are adept at mirroring others’ attitudes and behaviors to subtly manipulate situations in their favor (Hurley, 2005). When team members observe such adaptive strategies, they may also learn to adjust their approaches according to others, fostering smoother collaboration and facilitating deeper cross-understanding.

We further argue that a high level of cross-understanding fosters greater team creativity. Specifically, when cross-understanding is high, team members can more effectively recognize and absorb diverse knowledge, perspectives, and task-related information (Meslec & Graff, 2015). The articulation and elaboration of this information broaden collective learning (Nemeth & Kwan, 1987; Peterson & Nemeth, 1996), facilitate the integration of team knowledge, and ultimately enhance creativity. In addition, members tend to adapt their communication by using terms and concepts that others readily understand. This increases the acceptance and comprehension of their ideas (Krauss & Fussell, 1996), while reducing the likelihood of conversations that may trigger disagreement or conflict (Meslec & Graff, 2015), thereby improving communication efficiency and stimulating novel idea generation. Finally, awareness of what others know, believe, and value motivates members to explore the reasoning behind these views. Such extended discussions enrich interpretations of task-related issues (Huber & Lewis, 2010), encourage consideration of information that diverges from initial preferences, and stimulate divergent thinking and brainstorming—all of which contribute to higher levels of team creativity.

Hypothesis 2.

Machiavellian leadership positively influences team creativity through team cross-understanding.

2.4. The Moderating Role of Task Interdependence

Task interdependence, a fundamental characteristic of work, describes the degree to which a team member’s work depends on the contributions of other members, thereby requiring frequent interaction and coordination to accomplish tasks (Langfred, 2007). It has been associated with positive team processes such as helping, cooperation, and cohesion (Chen et al., 2009). Within the leadership–process–outcome model, task interdependence operates as a moderator (Liden et al., 2006). Accordingly, we argue that high task interdependence amplifies the positive effect of Machiavellian leadership on team cross-understanding.

High task interdependence requires team members to exchange information, advice, assistance, and resources to ensure effective task execution (Van Der Vegt et al., 1999). According to trait activation theory, such a context stimulates Machiavellian leaders to exhibit more pro-organizational and cooperative behaviors. Specifically, to promote harmonious interaction and efficient collaboration, Machiavellian leaders are likely to cultivate a climate supportive of communication, learning, and cooperation, while leveraging their sensitivity to others’ intentions, perspectives, and knowledge (Paal & Bereczkei, 2007). By observing these behaviors, team members are motivated to better understand others’ intentions and habits, share and absorb diverse knowledge, and embrace different viewpoints and practices, thereby enhancing cross-understanding (Meslec & Graff, 2015). Moreover, in highly interdependent teams, every member’s knowledge, resources, and skills are critical to collective success, necessitating frequent coordination and interaction (Langfred, 2007). This situation heightens Machiavellian leaders’ awareness of subordinates’ efforts (Khan et al., 2023) and prompts them to display charismatic leadership qualities—treating members fairly, recognizing subtle emotional or attitudinal shifts, tailoring communication and rewards to individual preferences, and striving to meet members’ resource needs. When members feel respected and valued, they develop stronger trust and belonging, which in turn motivates them to explore others’ perspectives and sensitivities, engage in deeper exchanges, and uncover the reasons behind their differences. Such processes ultimately strengthen cross-understanding within the team.

In contrast, when task interdependence is low, work tasks tend to be routine and largely independent, with individual responsibilities clearly defined and requiring minimal interaction (Van der Vegt et al., 2001). Under such conditions, Machiavellian leaders are less inclined to foster a climate of mutual communication and cooperation. Team members, in turn, adjust their behaviors by observing the leader, showing little motivation to understand others’ ways of thinking, work tasks, or expertise. Consequently, the level of cross-understanding within the team is likely to decline. Moreover, low task interdependence makes it difficult for both Machiavellian leaders and employees to recognize the importance of others’ contributions to task accomplishment. This context may activate leaders’ more self-serving traits—such as indifference and lack of empathy—leading them to focus resources and support on members they perceive as more essential, while displaying negative attitudes and behaviors toward others. Such selective treatment can generate dissatisfaction among team members, who, by observing the leader, may also adopt similarly narrow interaction patterns, showing friendliness only toward colleagues directly relevant to their own tasks. Over time, this dynamic undermines collaboration and gradually reduces cross-understanding within the team.

Hypothesis 3.

Task interdependence moderates the relationship between Machiavellian leadership and cross-understanding, such that the positive effect of Machiavellian leadership on cross-understanding is stronger when task interdependence is higher.

2.5. A Moderated Mediation Model

Based on Hypothesis 3, high task interdependence emphasizes the importance of collective effort and cooperation among team members (Mueller & Kamdar, 2011; Staples & Webster, 2008). Such a task context can motivate Machiavellian leaders to foster an environment that promotes open communication and mutual cooperation, while actively attending to each member’s psychological state and work progress. In this environment, team members are more likely to engage in interpersonal communication and mutual assistance with a positive mindset. They actively familiarize themselves with others’ work content and thinking patterns, incorporate others’ ideas into their own perspectives, and gradually build cross-understanding. As this understanding increases, members develop a stronger sense of belonging and work enthusiasm, further clarify shared goals, engage extensively in knowledge sharing and integration, and confidently express their own ideas. Such interaction and communication facilitate the emergence of creative ideas within the team.

In contrast, when task interdependence is low, team members can complete their tasks and perform well without engaging in communication or information exchange (Mitchell & Silver, 1990). Under these conditions, Machiavellian leaders may focus their attention on members most relevant to the team’s goals, neglecting the feelings and needs of others. Low task interdependence also signals to members that others’ task performance is unimportant—or even a potential threat—to their own performance (Katz-Navon & Erez, 2005). This can foster unhealthy competition among members. Negative influences from both the leader and other members can diminish team members’ sense of belonging, trust, work motivation, and team cohesion, thereby impeding cross-understanding. Consequently, members have fewer opportunities to learn about one another, engage in mutual learning, or deeply discuss divergent perspectives, and they lack the motivation to work toward collective goals. This, in turn, limits the generation of divergent thinking within the team. Therefore, we propose a moderated mediation:

Hypothesis 4.

Task interdependence positively moderates the mediating role of cross-understanding in the relationship between Machiavellian leadership and team creativity. Specifically, the mediating effect of cross-understanding is stronger when task interdependence is high and weaker when it is low.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants and Procedures

The team sample in this study was selected from technology enterprises in Shaanxi and Shandong provinces. We adopted a purposive sampling strategy, focusing on medium- and large-sized enterprises in the technology, manufacturing, and financial sectors, as these industries rely heavily on teamwork and innovation, making them suitable contexts for examining Machiavellian leadership and team creativity. To ensure data quality, questionnaires were administered on site in paper form by the researchers, and participants completed them anonymously. The study received approval from the Academic Committee of Shaanxi Normal University (NO. 202419049), and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Data collection took place between January and February 2025.

The research process consisted of two phases. In the pre-survey stage, we provided training for researchers, which included familiarizing them with the questionnaire and standardizing the survey procedures. We then conducted a pilot study in a company to ensure that the questionnaire structure was reasonable, the wording of the questions was clear, and the content was easy to understand. In the formal research phase, team members reported their demographic information, the level of task interdependence, and the level of cross-understanding within their teams. Team leaders provided basic team information, assessed their own level of Machiavellianism, and rated team creativity.

We carefully organized and entered the collected questionnaires; a total of 538 questionnaires were distributed. We eliminated invalid questionnaires with blank responses, consistent answers, and overly patterned responses. The final sample consisted of 379 team members and 86 team leaders, yielding an effective response rate of 86.43%. Among the 86 teams, the average team size is 6.73 members, and the average team age was 6.59 years. Most team leaders were male (62%). Their age distribution was 15% aged 24–28, 26% aged 29–33, 48% aged 34–43, and the remainder older than 43. The majority held a bachelor’s degree or higher. Among the 379 team members, 46% were women and 54% were men. Their age distribution was 29% aged 24–28, 33% aged 29–33, and 30% aged 34–43. Most also held a bachelor’s degree or higher.

3.2. Measures

The measures used in this study were adopted from established scales in prior research. Because the study was conducted in China, all English-language measures were translated into Chinese using the “translation/back-translation” procedure (Brislin, 1986) by a panel of bilingual experts. All items were rated on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

Machiavellian leadership. We measured Machiavellian leadership using the 16-item Machiavellian Personality Scale (Dahling et al., 2009), which has been employed in several empirical studies (Ramsay et al., 2023; Uppal & Bansal, 2023). An example item is “I’m willing to sabotage their efforts if others threaten me to achieve my goals” (Cronbach α = 0.936).

Cross-Understanding. Cross-understanding was assessed using a 5-item scale developed by Huber and Lewis (2010), which measures the extent to which team members understand each other’s mental models. This scale has been widely used in empirical research (Bayer & Lewis, 2013; Lewis & Herndon, 2015). An example item is “How well do you understand what it is that this member prefers”, with respect to the Capstone α of 0.852.

Task Interdependence. The task interdependence was measured using a 3-item scale developed by Campion et al. (1993). An example item was “Within my team, jobs performed by team members are related to one another” (Cronbach α = 0.787).

Team Creativity. Team leaders were asked to rate the creativity of their team using a 3-item measure adopted from Baer (2012). Leader ratings of team creativity are widely used in the literature (Lu et al., 2019; Y. Shin & Eom, 2014). An example item is “My team members approach problems in new ways” (Cronbach α = 0.763).

Control variables. Consistent with prior research, demographic characteristics such as gender, age, educational level can influence team creativity (S. J. Shin & Zhou, 2007; Shalley et al., 2004). In addition, team size and time tenure were also found to affect team creativity (Edwards & Lambert, 2007; Chiu et al., 2016). Therefore, we controlled for leaders’ and members’ age, gender, education level, as well as team size and team tenure.

3.3. Test of Measurement Models

3.3.1. Validity Analysis

Before conducting hypothesis testing, we verified the convergent and discriminant validity of the scales. As shown in Table 1, the results of the descriptive statistical analysis indicate that the means, variances and correlation coefficients of the four variables selected in this study were within the normal range. The average variance extracted (AVE) values for all the variables exceeded the recommended threshold of 0.50, except for Machiavellian leadership (AVE = 0.482). However, following Chin (1998), an AVE above 0.36 is considered acceptable, and therefore this value met the criterion. Still, we acknowledge that the slightly lower AVE indicates weaker convergent validity for this construct. However, the high composite reliability (CR = 0.937) provides additional support, and together these indices suggest that the measurement validity remains acceptable. The CR values for all variables were above 0.70, and the square root of AVE values were greater than the corresponding inter-construct correlation coefficients. Taken together, these results provide evidence of good convergent and discriminant validity for the four variables used in this study.

Table 1.

Results of convergent and discriminant validity analysis.

In addition, we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using Mplus 8.3 to assess the discriminant validity of all latent variables. The results indicated that the four-factor model provided a good fit to the data (X2/df = 1.6978; CFI = 0.961; TLI = 0.928; RMSEA = 0.067; SRMR = 0.072), supporting the discriminant validity of our measurement model.

To mitigate potential common method bias (CMB), we implemented statistical remedies using two techniques. First, Harman’s single-factor test was conducted via CFA by constraining all items to load onto a single latent factor. The resulting model explained 32.69% of the variance—well below the 50% benchmark—indicating that CMB was unlikely to be a serious concern. Second, we adopted the unmeasured latent method factor control (ULMC) approach, adding a method factor to the four-factor model. Comparisons between models revealed minimal changes in fit indices (∆CFI = 0.042, ∆TLI = 0.039, ∆RMSEA = 0.028), all smaller than the 0.05 threshold recommended by Bagozzi and Yi (1990) and Podsakoff et al. (2012). Collectively, these findings suggest that CMB had little impact on the study’s results.

3.3.2. Aggregation of Group-Level Variables

Because this study was conducted at the team level, it was necessary to aggregate individual-level variables to the team level before conducting validation analysis. We used Rwg, ICC (1), and ICC (2) to assess the appropriateness of aggregation. First, following James et al. (1984), we estimated the within-group agreement (Rwg) for each individual-level variable across team members. Median Rwg values above the recommended threshold of 0.70 were considered acceptable for aggregation. Second, intraclass correlation coefficients—ICC (1) and ICC (2)—were computed to further justify aggregation. Values above 0.12 for ICC (1) and 0.50 for ICC (2) indicate acceptable reliability (Glick, 1985). The results supported aggregation for both variables: cross-understanding (ICC (1) = 0.6815, ICC (2) = 0.9042, median Rwg = 0.9835) and task interdependence (ICC (1) = 0.2319, ICC (2) = 0.5702, median Rwg = 0.9678). These values met or exceeded conventional thresholds, providing sufficient justification for aggregating the measures to the team level.

3.4. Data Analysis

All analyses were conducted using SPSS 23.0 and Mplus 8.3 to test the study hypotheses. First, Hypothesis 1, which proposed a direct effect, was tested using linear regression. For the mediation effect (Hypothesis 2), we employed hierarchical regression following the classic procedure of Baron and Kenny (1986). To strengthen the robustness of the mediation test, we also used the bootstrapping method recommended by Shrout and Bolger (2002), which provides bias-corrected confidence intervals for indirect effects. For the moderation effect (Hypothesis 3), hierarchical regression with interaction terms was applied, and we further examined the significance of the interaction by plotting simple slopes. Hypothesis 4 proposed a moderated mediation effect, which was tested by integrating the above approaches. Following Aiken et al. (1991), all continuous variables were mean-centered prior to creating interaction terms to minimize multicollinearity.

4. Results

Hypothesis 1 proposed that Machiavellian leadership is positively related to team creativity. The regression results (Table 2, Model 1) revealed that Machiavellian leadership had a significant positive effect on team creativity (β = 0.229, p = 0.01), supporting Hypothesis 1. This finding suggests that, despite its dark reputation, Machiavellian leadership may contribute to creative outcomes when examined at the team level.

Table 2.

Regression analysis results.

Hypothesis 2 predicted that cross-understanding would mediate the positive relationship between Machiavellian leadership and team creativity. As shown in Table 2, Model 3, Machiavellian leadership was positively related to cross-understanding (β = 0.497, p < 0.001). When cross-understanding was included as a control, the impact of Machiavellian leadership on team creativity became non-significant (β = 0.029, p = 0.729). This pattern indicates that cross-understanding fully mediated the direct effect of Machiavellian leadership on team creativity, thus supporting Hypothesis 2. Consistent with Shrout and Bolger’s (2002) recommendation, we conducted bootstrapping test using the PROCESS macro. The results confirmed that cross-understanding had a significant mediating effect, with a 95% confidence interval of [0.1084, 0.3172]. Together, these results highlight the pivotal role of cross-understanding as a cognitive mechanism that explains how Machiavellian leadership translates into team creativity.

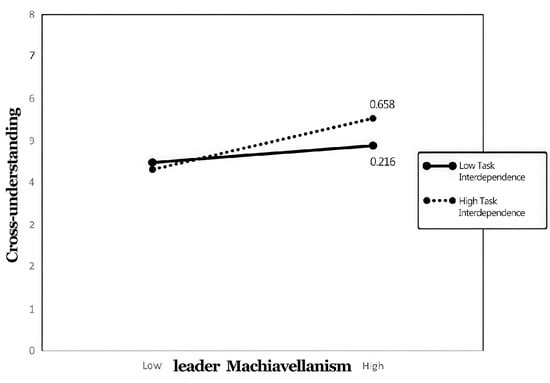

Hypothesis 3 proposed that task interdependence enhances the positive effect of leader Machiavellianism on cross-understanding. As shown in Table 2, Model 4, the interaction term was significant (β = 0.483, p < 0.01), supporting Hypothesis 3. To better understand the interaction effect, we adopted Aiken et al.’s (1991) recommendation, plotted the simple slopes at +1 SD of task interdependence (see Figure 2). The slope was substantially steeper (0.658) under high task interdependence, suggesting that Machiavellian leaders are more effective at fostering cross-understanding when team members’ work is strongly interdependent.

Figure 2.

The moderating effect of task interdependence on the relationship between leader Machiavellianism and cross-understanding.

Hypothesis 4 posited a moderated mediation effect, whereby task interdependence moderates the indirect relationship between leader Machiavellianism and team creativity through cross-understanding. To test this, we conducted a moderated path analysis (Edwards & Lambert, 2007) in Mplus 8.3 with 2000 bootstrapped samples to obtain bias-corrected confidence intervals for significance testing. The results in Table 3 showed that task interdependence significantly moderated the indirect effect. Specifically, the indirect effect was stronger when task interdependence was high (β = 0.128, 95% CI [0.030, 0.233]) than when it was low (β = 0.045, 90% CI [0.005, 0.124]). Thus, Hypothesis 4 was supported. This pattern confirms that the influence of Machiavellian leadership on team creativity is conditional: it is most pronounced in contexts characterized by high interdependence.

Table 3.

Results of moderated mediation.

5. Discussion

This study set out to examine whether Machiavellian leaders—typically associated with manipulation and self-interest—can, under certain conditions, foster team creativity. The findings show that Machiavellian leadership does not directly enhance creativity but contributes indirectly through cross-understanding, particularly when supported by high task interdependence. In this way, Machiavellian leaders may still promote positive outcomes, aligning with recent research that highlights the adaptive potential of dark traits in organizational contexts (Lebuda et al., 2021; Doornenbal et al., 2022), while extending prior work from individual to team-level processes. At the same time, our results diverge from studies emphasizing the harmful effects of Machiavellianism on trust and collaboration (Kiazad et al., 2010), suggesting that contextual factors such as task design determine whether these leaders hinder or foster creativity. Building on recent calls for stronger theory development in management research, we position our study as moving beyond describing “what leaders do” to explaining “why they do it.” The context of Chinese technology enterprises provides a unique lens, as these settings combine rapid innovation demands with collectivist cultural values, sharpening theoretical insights into how Machiavellian leaders strategically adapt their behaviors to situational demands and enriching trait activation theory across cultural contexts.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

First, by examining the link between dark trait leadership and team creativity—focusing specifically on Machiavellian leadership—we extend prior research and respond to calls for exploring team creativity from a “dark side” perspective (Anderson et al., 2014). This study constructed and empirically validated a theoretical model linking Machiavellian leadership, cross-understanding, task interdependence, and team creativity. Importantly, while regression results initially suggested a positive association between Machiavellian leadership and team creativity (Hypothesis 1), this direct effect disappeared once cross-understanding was introduced as a mediator. This indicates that Machiavellian leadership does not foster creativity directly, but rather influences creativity only indirectly through team processes. This finding deepens our understanding of how dark leadership traits may, under certain conditions, contribute to positive team outcomes.

Second, our results highlight the mediating role of cross-understanding. Previous studies have mainly focused on mechanisms involving leader behaviors, follower emotions, or follower behaviors, but have paid less attention to team-level cognitive processes. By showing that Machiavellian leadership enhances creativity exclusively through cross-understanding, our study identifies this team-level emergent cognition as the critical pathway to explain why teams led by leaders with dark traits can still achieve high creativity. This reframes the role of Machiavellian leaders: rather than directly driving creativity, they shape the team interactions that enable members to integrate diverse perspectives and generate novel ideas. This expands the literature by linking social learning theory with emergent team cognition, thereby clarifying how team-level interactions serve as the “black box” between Machiavellian leadership and team creativity.

Third, by identifying task interdependence as a critical contextual moderator, we broaden the understanding of how Machiavellian leadership manifests and operates across different contexts. Our results show that under high task interdependence, Machiavellian leaders have stronger incentives to enact cooperative behaviors that facilitate cross-understanding and creativity. This situational perspective helps explain conflicting results in the literature—where some studies emphasize the harmful effects of Machiavellianism on trust and collaboration (Kiazad et al., 2010), whereas others note its adaptive potential in organizational contexts (Lebuda et al., 2021; Doornenbal et al., 2022). By clarifying this contextual boundary, we underscore the context-dependent nature of Machiavellian leadership and reconcile these divergent findings.

Finally, building on recent calls for stronger theory development in management research, we draw on Homer and Lim (2024) to position our work as moving beyond describing “what leaders do” to explaining “why they do it.” Using Chinese technology enterprises as the empirical context provides a unique lens, as these environments combine rapid innovation demands with collectivist cultural values. This context sharpens theoretical insights into how Machiavellian leaders strategically adapt their behaviors to align with situational demands, thereby enriching trait activation theory and extending its application to cross-cultural settings

5.2. Practical Implications

Innovation is considered a key factor in creating sustainable competitive advantage for organizations, with organizations often relying on teams to generate and implement novel ideas, processes, products, and procedures (Eisenbeiss et al., 2008; Hülsheger et al., 2009). This study investigates how Machiavellian leaders influence team creativity, along with its mediating mechanisms and boundary conditions. It sheds light on why leaders with dark traits (Machiavellianism)—often perceived as visionary yet demanding—can still guide teams and organizations toward high innovation performance, while also underscoring the potential risks of trust erosion and manipulation. In doing so, it provides managers with a more balanced perspective for designing practical strategies that harness short-term creative benefits while mitigating long-term organizational risks. First, this study shows that Machiavellian leadership exerts a positive indirect effect on team creativity. Rather than avoiding the appointment of leaders with Machiavellian tendencies, organizations should channel their ambition toward innovation as a foundation for enhancing creativity. For example, setting clearly, measurable innovation goals combined with targeted incentives such as bonuses and promotions can effectively stimulate leaders’ motivation to innovate. At the same time, organizations should remain vigilant. Over time, Machiavellian leaders’ manipulative behaviors can undermine trust (H. Li et al., 2024), increase employee abusive supervision (Rus et al., 2025), and trigger turnover (J. Li et al., 2019) if left unchecked. Thus, risk management practices—such as regular performance reviews, 360-degree feedback, and clear accountability mechanisms—are essential to prevent long-term harm. Second, the study identifies team cross-understanding as an important mechanism linking Machiavellian leadership to team creativity. Managers can strengthen this mechanism by holding regular team workshops that encourage open communication among members and reduce the pressure to constantly display competence. Managers should also foster psychological safety so that team members feel secure in sharing unconventional ideas and pursuing creative risks (Silvia et al., 2011). Additionally, managers can implement “profile exchange” activities, requiring team members review and discuss one another’s expertise, beliefs, and preferences (Huber & Lewis, 2010). However, managers should also monitor whether leaders exploit these exchanges for manipulation or self-interest, as such misuse could weaken team trust and cohesion over the longer term.

Third, task interdependence amplifies the positive effects of Machiavellian leadership on both cross-understanding and team creativity. To leverage this, managers can design workflows and project structures that require frequent collaboration and information sharing, ensuring that tasks are interconnected. This could involve forming cross-functional project teams, assigning shared performance targets, and linking individual rewards to team-level achievements. Building an organizational culture of solidarity and cooperation is equally important. Leaders can schedule regular team check-ins, host collaborative problem-solving sessions, and conduct team-based performance reviews to reinforce shared ownership of results. Still, excessive reliance on Machiavellian leaders in highly interdependent contexts may create hidden vulnerabilities, as short-term creativity gains could be offset by long-term trust erosion and declining employee commitment. Organizations should therefore balance leader-driven influence with broader structural safeguards and culture-building initiatives

5.3. Limitations and Future Directions

Although this study provides novel insights into Machiavellian leadership and team creativity, several limitations must be acknowledged, which also offer directions for future research.

First, this study measured team creativity using leaders’ subjective self-assessments. However, highly novel ideas are often less likely to be recognized by leaders, particularly when their time and cognitive resources are limited (Lu et al., 2019). In addition, Machiavellian leaders may overestimate their teams’ creativity to validate their own effectiveness or maintain a positive self-image. Although conducting the analysis at the group level enabled us to capture team-level dynamics, it limited our ability to disentangle individual perceptions from collective processes. Future research could adopt multilevel or mixed-method designs to better integrate individual and group perspectives. This would improve measurement accuracy by combining leader assessments with in-depth interviews involving both leaders and team members, as well as incorporating objective indicators such as records of submitted creative ideas or creativity-related awards over a specific time period (Shrout & Bolger, 2002). Second, the data were collected from technology, manufacturing, and financial firms in Shaanxi and Shandong provinces in China, encompassing 86 teams and 379 individuals. While this relatively large and diverse sample enhances representativeness, the findings may still be shaped by the specific industrial and cultural context. Cultural characteristics such as high collectivism and respect for hierarchy may have amplified the effects observed in this study, thereby limiting the generalizability of the results to other cultural settings. Future research should replicate the model across a broader range of industries and in diverse cultural and institutional contexts to better examine the boundary conditions of these findings.

Third, while this study highlights task interdependence as a key boundary condition in the relationship between Machiavellian leadership and team creativity, future research could incorporate additional boundary conditions to better capture the contexts in which the positive effects of Machiavellian leadership on team creativity are most likely to emerge. Future longitudinal studies are needed to examine the long-term consequences of working with Machiavellian leaders, and how Machiavellian leadership influences creativity over time, particularly whether short-term benefits are offset by longer-term risks such as trust erosion or turnover.

Finally, this study focused exclusively on Machiavellianism. As prior research has examined the relationship between each dimension of the Dark Triad and creativity—with psychopathy in particular often linked to creative tendencies (Lebuda et al., 2021)—future research could compare the differential effects of Machiavellianism, narcissism, and psychopathy on creativity. Such comparisons would clarify whether the mechanisms identified here are unique to Machiavellian leadership or generalizable across dark traits.

6. Conclusions

This study examined how Machiavellian leadership shapes team creativity through the mediating role of cross-understanding and the moderating role of task interdependence. The results show that Machiavellian leadership does not directly enhance creativity but fosters it indirectly when contextual conditions align with leader self-interest. These findings enrich theory by moving beyond the predominantly negative view of dark traits and clarifying when such leadership can promote constructive outcomes.

Theoretically, our study advances leadership and creativity research in three ways. First, it demonstrates that Machiavellian leadership can be a double-edged sword, revealing that its influence is contingent on team-level processes and task design. Second, it highlights cross-understanding as a critical mechanism through which leaders shape collective creativity, thereby extending social learning theory to the team level. Third, by identifying task interdependence as a boundary condition, the study extends trait activation theory and clarifies how situational demands can channel dark traits into adaptive behaviors.

Practically, this study offers managers a balanced perspective. While Machiavellian leaders may stimulate creativity in highly interdependent teams, their manipulative tendencies also pose risks of trust erosion and turnover. Organizations should therefore align leader goals with collective objectives and adopt safeguards—such as accountability systems, feedback mechanisms, and long-term monitoring—to mitigate risks while capturing potential creative benefits.

Future research should adopt multi-source and longitudinal designs, test additional boundary conditions, and compare different dark traits (narcissism, psychopathy) to build a more comprehensive understanding of leadership and creativity across diverse cultural and organizational settings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Y.; methodology, Y.Y. and X.Q.; formal analysis, Y.Y. and H.X.; investiga-tion, H.X. and Y.L.; data curation, H.X. and Y.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Y.; writ-ing—review and editing, X.Q. and H.L.; supervision, X.Q. and H.L.; project administration, H.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Academic Committee of Shaanxi Normal University approved this study (protocol code: 202419049 and approved on 12 November 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are not publicly available due to confidentiality restrictions, but the data presented in this study can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Adam, D. (2019). Does a ‘dark triad’ of personality traits make you more successful? Science|AAAS. Available online: https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2019/03/does-dark-triad-personality-traits-make-you-more-successful (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Aiken, L. S., West, S. G., & Reno, R. R. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Al Harbi, J. A., Alarifi, S., & Mosbah, A. (2019). Transformation leadership and creativity: Effects of employees pyschological empowerment and intrinsic motivation. Personnel Review, 48(5), 1082–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, N., Potočnik, K., & Zhou, J. (2014). Innovation and creativity in organizations: A state-of-the-science review, prospective commentary, and guiding framework. Journal of Management, 40(5), 1297–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer, M. (2012). Putting creativity to work: The implementation of creative ideas in organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 55(5), 1102–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R. P., & Yi, Y. (1990). Assessing method variance in multitrait-multimethod matrices: The case of self-reported affect and perceptions at work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 75(5), 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y., Lin, L., & Liu, J. T. (2019). Leveraging the employee voice: A multi-level social learning perspective of ethical leadership. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 30(12), 1869–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action (p. 2). Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A., & Walters, R. H. (1977). Social learning theory. Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayer, M., & Lewis, K. (2013, August 9–13). Cross-understanding, coordination, and performance. Academy of Management Annual Meeting, Orlando, FL, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Biscaro, C., & Montanari, F. (2025). A cognitive network perspective on creativity: Theorizing network mobilization scripts. Organization Science, 36(2), 626–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R. W. (1986). The wording and translation of research instruments. In W. J. Lonner, & J. W. Berry (Eds.), Field methods in cross-cultural research (pp. 137–164). Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Campion, M. A., Medsker, G. J., & Higgs, A. C. (1993). Relations between work group characteristics and effectiveness: Implications for designing effective work groups. Personnel Psychology, 46(4), 823–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capezio, A., Wang, L., Restubog, S. L., Garcia, P. R., & Lu, V. N. (2017). To flatter or to assert? Gendered reactions to Machiavellian leaders. Journal of Business Ethics, 141, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. H. V., Tang, Y. Y., & Wang, S. J. (2009). Interdependence and organizational citizenship behavior: Exploring the mediating effect of group cohesion in multilevel analysis. The Journal of Psychology, 143(6), 625–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W. W. (1998). Commentary: Issues and opinion on structural equation modeling. MIS Quarterly, 22, 7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, C.-Y., Owens, B. P., & Tesluk, P. E. (2016). Initiating and utilizing shared leadership in teams: The role of leader humility, team proactive personality, and team performance capability. Journal of Applied Psychology, 101(12), 1705–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutifaris, C. G. V., & Grant, A. M. (2021). Taking your team behind the curtain: The effects of leader feedback-sharing and feedback-seeking on team psychological safety. Organization Science, 33(6), 1574–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahling, J. J., Whitaker, B. G., & Levy, P. E. (2009). The development and validation of a new Machiavellianism Scale. Journal of Management, 35(2), 219–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Hoogh, A. H. B., Den Hartog, D. N., & Belschak, F. D. (2021). Showing one’s true colors: Leader Machiavellianism, rules and instrumental climate, and abusive supervision. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 42(7), 851–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doornenbal, B. M., Spisak, B. R., & van der Laken, P. A. (2022). Opening the black box: Uncovering the leader trait paradigm through machine learning. The Leadership Quarterly, 33(5), 101515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drory, A., & Gluskinos, U. M. (1980). Machiavellianism and leadership. Journal of Applied Psychology, 65(1), 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J. R., & Lambert, L. S. (2007). Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: A general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychological Methods, 12(1), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenbeiss, S. A., Van Knippenberg, D., & Boerner, S. (2008). Transformational leadership and team innovation: Integrating team climate principles. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(6), 1438–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faeq, D. K., Hama, P. F., & Demir, A. (2024). Impact of Machiavellian leadership on employee grievances and creative performance: The mediating role of job insecurity. Journal of Southwest Jiaotong University, 59(4), 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z., Keng-Highberger, F., Yam, K. C., Chen, X. P., & Li, H. (2022). Wolves in sheep’s clothing: How and when Machiavellian leaders demonstrate strategic abuse. Journal of Business Ethics, 184(1), 255–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genau, H. A., Blickle, G., Schütte, N., & Meurs, J. A. (2022). Machiavellian leader effectiveness. Journal of Personnel Psychology, 21(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glick, W. H. (1985). Conceptualizing and measuring organizational and psychological climate: Pitfalls in multilevel research. Academy of Management Review, 10(3), 601–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenbaum, R. L., Hill, A., Mawritz, M. B., & Quade, M. J. (2017). Employee Machiavellianism to unethical behavior: The role of abusive supervision as a trait activator. Journal of Management, 43(2), 585–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunnthorsdottir, A., McCabe, K., & Smith, V. (2002). Using the Machiavellianism instrument to predict trustworthiness in a bargaining game. Journal of Economic Psychology, 23(1), 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirst, G., Van Knippenberg, D., & Zhou, J. (2009). A cross-level perspective on employee creativity: Goal orientation, team learning behavior, and individual creativity. Academy of Management Journal, 52(2), 280–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoegl, M., & Gemuenden, H. G. (2001). Teamwork quality and the success of innovative projects: A theoretical concept and empirical evidence. Organization Science, 12(4), 435–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homer, S. T., & Lim, W. M. (2024). Theory development in a globalized world: Bridging “Doing as the Romans Do” with “Understanding Why the Romans Do It”. Global Business and Organizational Exeellence, 43(3), 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, G. P., & Lewis, K. (2010). Cross-understanding: Implications for group cognition and performance. Academy of Management Review, 35(1), 6–26. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, D. J., Lee, A., Tian, A. W., Newman, A., & Legood, A. (2018). Leadership, creativity, and innovation: A critical review and practical recommendations. The Leadership Quarterly, 29(5), 549–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurley, S. (2005). Social heuristics that make us smarter. Philosophical Psychology, 18, 585–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hülsheger, U. R., Anderson, N., & Salgado, J. F. (2009). Team-level predictors of innovation at work: A comprehensive meta-analysis spanning three decades of research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(5), 1128–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilgen, D. R., Hollenbeck, J. R., Johnson, M., & Jundt, D. (2005). Teams in organizations: From input-process-output models to IMOI models. Annual Review of Psychology, 56, 517–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, L. R., Demaree, R. G., & Wolf, G. (1984). Estimating within-group interrater reliability with and without response bias. Journal of Applied Psychology, 69(1), 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janardhanan, N. S., Lewis, K., Reger, R. K., & Stevens, C. K. (2020). Getting to know you: Motivating cross-understanding for improved team and individual performance. Organization Science, 31(1), 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonason, P. K., Richardson, E. N., & Potter, L. (2015). Self-reported creative ability and the dark triad traits: An exploratory study. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 9(4), 488–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D. N., & Paulhus, D. L. (2009). Machiavellianism. In M. R. Leary, & R. H. Hoyle (Eds.), Handbook of individual differences in social behavior (pp. 93–108). The Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Katz-Navon, T. Y., & Erez, M. (2005). When collective-and self-efficacy affect team performance: The role of task interdependence. Small Group Research, 36(4), 437–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keng-Highberger, F., Feng, Z., Yam, K. C., Chen, X.-P., & Li, H. (2024). Middle power plays: How and when mach middle managers use downward abuse and upward guanxi to gain and maintain power. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 45(7), 1088–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A. K., Hameed, I., Quratulain, S., Arain, G. A., & Newman, A. (2023). How the supervisor’s Machiavellianism results in abusive supervision: Understanding the role of the supervisor’s competitive worldviews and subordinate’s performance. Personnel Review, 52(4), 992–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiazad, K., Restubog, S. L. D., Zagenczyk, T. J., Kiewitz, C., & Tang, R. L. (2010). In pursuit of power: The role of authoritarian leadership in the relationship between supervisors’ Machiavellianism and subordinates’ perceptions of abusive supervisory behaviour. Journal of Research in Personality, 44, 512–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauss, R. M., & Fussell, S. R. (1996). Social psychological models of interpersonal communication. In E. T. Higgins, & A. W. Kruglanski (Eds.), Social psychology: Handbook of basic principles (pp. 655–701). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Langfred, C. W. (2007). The downside of self-management: A longitudinal study of the effects tf conflict on trust, autonomy, and task interdependence in self-managing teams. Academy of Management Journal, 50(4), 885–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebuda, I., Figura, B., & Karwowski, M. (2021). Creativity and the dark triad: A meta-analysis. Journal of Research in Personality, 92, 104088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LePine, J. A. (2005). Adaptation of teams in response to unforeseen change: Effects of goal difficulty and team composition in terms of cognitive ability and goal orientation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 1153–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, K., & Herndon, B. D. (2015). Cross-understanding and power: How being understood affects influence and performance. In Individual perspectives and emergent team information processes (Symposium). Proceedings of the Academy of Management Annual Meeting (Vancouver, Canada, August 2015). (N. S. Janardhanan, & C. A. Bartel Chairs). Academy of Management. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H., Huang, S., & Feng, Z. (2024). The complexity of Machiavellian leaders: How and when leader Machiavellianism impacts abusive supervision. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 42, 1743–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Bonn, M. A., & Ye, B. H. (2019). Hotel employee’s artificial intelligence and robotics awareness and its impact on turnover intention: The moderating roles of perceived organizational support and competitive psychological climate. Tourism Management, 73, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liden, R. C., Erdogan, B., Wayne, S. J., & Sparrowe, R. T. (2006). Leader-member exchange, differentiation, and task interdependence: Implications for individual and group performance. Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior, 27(6), 723–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S., Bartol, K. M., Venkataramani, V., Zheng, X., & Liu, X. (2019). Pitching novel ideas to the boss: The interactive effects of employees’ idea enactment and influence tactics on creativity assessment and implementation. Academy of Management Journal, 62(2), 579–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainemelis, C., Kark, R., & Epitropaki, O. (2015). Creative leadership: A multi-context conceptualization. Academy of Management Annals, 9(1), 393–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marbut, A. R., Harms, P. D., & Credé, M. (2025). In the service of the prince: A meta-analytic review of machiavellian leadership. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 46, 939–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meslec, N., & Graff, D. (2015). Being open matters: The antecedents and consequences of cross-understanding in teams. Team Performance Management, 21(1–2), 6–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, T. R., & Silver, W. S. (1990). Individual and group goals when workers are interdependent: Effects on task strategies and performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 75(2), 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, J. S., & Kamdar, D. (2011). Why seeking help from teammates is a blessing and a curse: A theory of help seeking and individual creativity in team contexts. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(2), 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nemeth, C. J., & Kwan, J. L. (1987). Minority influence, divergent thinking and detection of correct solutions. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 17(9), 788–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, C. S., Kaufman, S. B., ten Brinke, L., Yaden, D. B., Hyde, E., & Tsykayama, E. (2020). Light and dark trait subtypes of human personality—A multi-study person-centered approach. Personality and Individual Differences, 164, 110121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paal, T., & Bereczkei, T. (2007). Adult theory of mind, cooperation, Machiavellianism: The effect of mindreading on social relations. Personality and Individual Differences, 43(3), 541–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulhus, D. L., & Williams, K. M. (2002). The dark triad of personality: Narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy. Journal of Research in Personality, 36, 556–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, R. S., & Nemeth, C. J. (1996). Focus versus flexibility majority and minority influence can both improve performance. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22(1), 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63(1), 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsay, J. E., Wang, D., Yeo, J. S., Khong, Z. Y., & Tan, C. S. (2023). Perceived authenticity, Machiavellianism, and psychological functioning: An inter-domain and cross-cultural investigation. Personality and Individual Differences, 204, 112049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, N., Duarte, A. P., Filipe, R., & Torres de Oliveira, R. (2020). How authentic leadership promotes individual creativity: The mediating role of affective commitment. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 27(2), 189–202. [Google Scholar]

- Rus, D., Sleebos, E., & Wisse, B. (2025). Fear is the path to the dark side: The interplay of leader fear of power loss and leader Machiavellianism on abusive supervision. Journal of Managerial Psychology. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakalaki, M., Richardson, C., & Thepaut, Y. (2007). Machiavellianism and economic opportunism. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 37(6), 1181–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas, E., Cooke, N. J., & Rosen, M. A. (2008). On teams, teamwork, and team performance: Discoveries and developments. Human Factors, 50(3), 540–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satornino, C. B., Allen, A., Shi, H., & Bolander, W. (2023). Understanding the performance effects of “Dark” salesperson traits: Machiavellianism, narcissism, and psychopathy. Journal of Marketing, 87(2), 298–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalley, C. E., Zhou, J., & Oldham, G. R. (2004). The effects of personal and contextual characteristics on creativity: Where should we go from here? Journal of Management, 30(6), 933–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S. J., & Zhou, J. (2007). When is educational specialization heterogeneity related to creativity in research and development teams? Transformational leadership as a moderator. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(6), 1709–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, Y., & Eom, C. (2014). Team proactivity as a linking mechanism between team creative efficacy, transformational leadership, and risk-taking norms and team creative performance. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 48(2), 89–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrout, P. E., & Bolger, N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7(4), 422–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvia, P. J., Kaufman, J. C., Reiter-Palmon, R., & Wigert, B. (2011). Cantankerous creativity: Honesty–humility, agreeableness, and the HEXACO structure of creative achievement. Personality and Individual Differences, 51(5), 687–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staples, D. S., & Webster, J. (2008). Exploring the effects of trust, task interdependence and virtualness on knowledge sharing in teams. Information Systems Journal, 18(6), 617–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tett, R. P., Simonet, D. V., Walser, B., & Brown, C. (2013). Trait activation theory: Applications, developments, and implications for person–workplace fit. In Handbook of personality at work (pp. 71–100). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Uppal, N., & Bansal, A. (2023). A study of trickle-down effects of leader Machiavellianism on follower unethical behaviour: A social learning perspective. Personality and Individual Differences, 207, 112171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Vegt, G., Emans, B., & Van De Vliert, E. (1999). Effects of interdependencies in project teams. The Journal of Social Psychology, 139(2), 202–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Vegt, G., Emans, B., & Van De Vliert, E. (2001). Patterns of interdependence in work teams: A two-level investigation of the relations with job and team satisfaction. Personnel Psychology, 54(1), 51–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wageman, R. (1995). Interdependence and group effectiveness. Administrative Science Quarterly, 40, 145–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wageman, R., & Gordon, F. M. (2005). As the twig is bent: How group values shape emergent task interdependence in groups. Organization Science, 16(6), 687–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z., Zhang, R., Qu, Y., Cai, S., Chen, F., & Zhang, H. (2025). Participative leadership and team creativity: The role of team intellectual capital and colleague social support. Knowledge Management Research & Practice, 23(3), 323–333. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).