1. Introduction

The contemporary organizational landscape is dynamic and complex, requiring organizations and their employees to be able to adapt and be resilient. Leadership emerges as a critical factor for organizational success or failure. However, not all leadership characteristics or behaviors promote healthy and productive environments. Narcissistic leaders, often charismatic figures with ambitious visions for innovation and change, have a remarkable early ability to magnetize employees to work with and for them (

Choi & Phan, 2022;

Rosenthal & Pittinsky, 2006). This initial attraction, often driven by the charisma and social skills of narcissistic leaders, often turns into a deep aversion as the hidden face of narcissism reveals itself (

Choi & Phan, 2022). Narcissistic leadership, characterized by their self-serving behaviors and lack of empathy (

Rosenthal & Pittinsky, 2006), has been increasingly recognized as a significant source of dysfunction and dissatisfaction in the workplace (e.g.,

Wang et al., 2021,

2022;

Yousif & Loukil, 2022). These types of leaders, motivated by their own needs and beliefs, demonstrated that may engage in unethical practices and contribute to a toxic work environment (e.g.,

Azazz et al., 2024;

Fehn & Schütz, 2021;

Gauglitz et al., 2023). Research into the effects of narcissistic leadership, particularly when evaluated by followers, has not shown consistent results on whether it could be beneficial or detrimental (

Braun, 2017;

Nevicka et al., 2018), indicating the need for additional exploration into the underlying mechanisms that lead to these different outcomes. The present study seeks to fill this gap by specifically investigating the relationship between narcissistic leadership and its potential negative effects, focusing on employees’ intention to leave. While narcissistic leaders are known to foster detrimental work environments, the direct link to employees’ desire to leave the organization (i.e., turnover intention) is often complex. Turnover intention refers to an employee’s self-stated likelihood or intention to leave their current job or organization (

Hinshaw & Atwood, 1984;

de Sul & Lucas, 2020). The negative effects of narcissistic leadership, such as abusive supervision (

Gauglitz et al., 2023), decreased job satisfaction (

Yousif & Loukil, 2022), and increased burnout (

Bernerth, 2022) are theoretical precursors to turnover intention. However, the mere presence of a narcissistic leader does not fully explain the intention of rotation, since it might be explained by other individual and contextual factors, which can mediate or moderate this relationship. It is necessary to explore how employees’ features and competences, namely their Psychological Capital (PsyCap), can be affected by narcissistic leadership to ultimately influence their decision to stay or leave the organization.

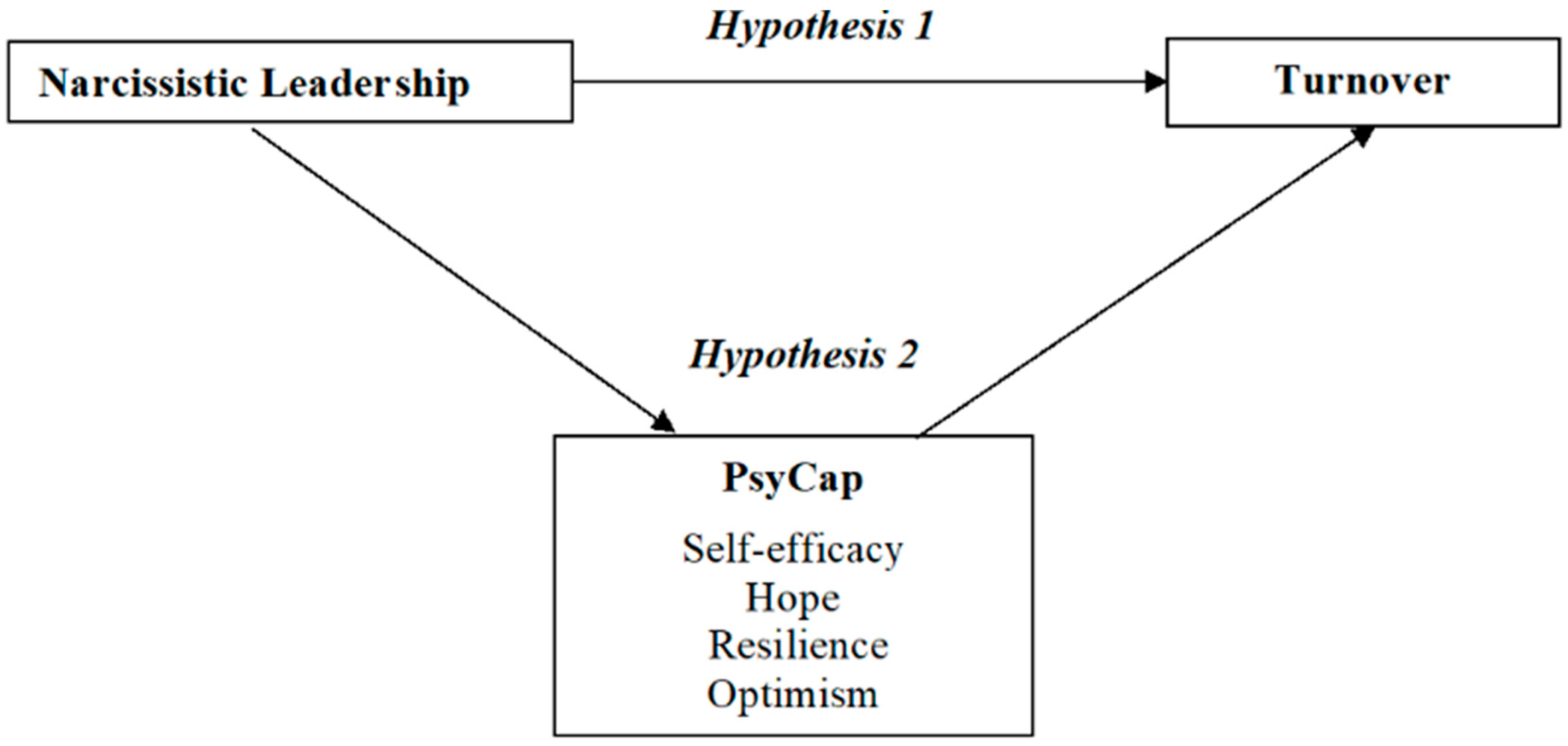

The current research is grounded in the job demands-resources theory (JD-R) (

Bakker et al., 2023) to understand the relationship between narcissistic leadership and turnover intention and the role of psychological capital in this relationship. Narcissistic leadership is considered a job demand. Psychological capital is understood as a personal resource and can be considered a potential mediating variable in this relationship. Narcissistic leadership can deplete employees’ psychological resources (psychological capital), leading them to desire to leave the organization. Additionally, drawing on positive psychology, we argue that the adverse impact of narcissistic leadership on turnover intention is explained by its preceding negative effect on employees’ psychological capital (comprising hope, self-efficacy, resilience, and optimism). Specifically, a leader’s narcissistic behaviors are hypothesized to deplete employees’ psychological resources, thereby increasing their propensity to seek alternative employment. This research aims to assess how narcissistic leadership is positively related to turnover, highlighting the critical role of psychological capital as a mediator of this association. Anticipating and analyzing these variables can provide managers, leaders, and human resources relevant information, allowing them to develop strategies for retaining talent within the organization. We intend not only to underline the importance of addressing the challenges posed by dysfunctional leadership, but also to highlight the potential of promoting psychological capital as a strategic tool to promote talent retention and build more resilient organizations.

1.1. Hypothesis Development

1.1.1. Narcissistic Leadership and Turnover Intention

Narcissistic leadership occurs when leaders’ actions are predominantly motivated by their own egomaniacal needs and beliefs, superseding the needs and interests of the constituents and institutions they lead (

Rosenthal & Pittinsky, 2006). This definition allows for a more comprehensive and integrated look at the role of narcissism in leadership by highlighting the psychological motivation of narcissistic leaders and taking into account the contexts in which leadership occurs. Narcissistic leadership is characterized by leaders who exhibit traits such as grandiosity, arrogance, self-absorption, entitlement, and a lack of empathy (

Rosenthal & Pittinsky, 2006). Leaders demonstrating grandiosity and arrogance often have an inflated sense of their own importance and abilities (

Milligan et al., 2022;

Rosenthal & Pittinsky, 2006). These leaders are highly focused on their own needs and desires, often ignoring the needs of others (

Rosenthal & Pittinsky, 2006;

Wang et al., 2022), and they may believe they deserve special treatment and privileges (

Milligan et al., 2022;

Rosenthal & Pittinsky, 2006). Furthermore, these leaders typically show little concern for the feelings and needs of others (

Milligan et al., 2022;

Yousif & Loukil, 2022) and may react aggressively to criticism or perceived threats to their self-esteem (

Gauglitz et al., 2023;

Nevicka et al., 2013). Also, they are primarily motivated by self-interest and the need for admiration, often at the expense of their followers and organizations (

Milligan et al., 2022;

Rosenthal & Pittinsky, 2006;

Yousif & Loukil, 2022;

Wang et al., 2022).

In the field of organizational leadership, studies on narcissism have consistently distinguished between narcissistic leadership emergence and its effectiveness (e.g.,

Campbell et al., 2011;

Sedikides & Campbell, 2017). Leadership emergence is frequently driven by narcissism, since individuals showing these traits actively seek positions of power and status and are particularly adept at projecting an image of a prototypically effective leader (

Nevicka et al., 2011,

2013). Certain individuals become leaders, particularly in group contexts, without a formally designated leader (

Brunell et al., 2008). However, a mere emergence into leadership positions does not guarantee its effectiveness. Narcissistic leaders possess a complex array of characteristics that can be both positive and negative, which may differentially determine their effectiveness. On the bright side, narcissistic leaders can be extremely charismatic and have a bold vision, which may inspire and motivate followers (

Buss et al., 2024;

Nevicka et al., 2013;

Rosenthal & Pittinsky, 2006). This can be beneficial not only for the narcissistic individual but also for the whole organization (

Sedikides & Campbell, 2017). Conversely, the negative characteristics associated with narcissistic leaders often lead to detrimental outcomes for organizations and their employees (

Ong et al., 2016). Narcissistic leaders are frequently perceived as abusive, particularly by followers with low self-esteem (

Gauglitz et al., 2023;

Nevicka et al., 2018). And it is expected that this abusive behavior could lead to an increase in intent to leave due to the toxic work environment. In fact, leader’s self-centered behavior can result in reduced employee performance, diminished creativity, decreased job satisfaction, and increased rates of burnout and turnover (

Wang et al., 2022;

Wang et al., 2021;

Yousif & Loukil, 2022). Also, employees who perceive their leaders as inconsistent and abusive are more likely to consider leaving the organization (

Van Gerven et al., 2022;

Yousif & Loukil, 2022).

Employee turnover is a critical issue for all organizations. Turnover intention refers to the predisposition of a worker to abandon the present position (department/unit), the organization, or even the profession (

de Sul & Lucas, 2020).

Nguyen et al. (

2023) describe turnover intention as a person’s willingness to leave their current employment while still capable and employed. This willingness is often studied as a predictor of actual employee turnover, which can have significant implications for organizational stability and performance. Research has demonstrated a strong positive relationship between the intention to leave a job and effectively doing so (e.g.,

Galletta et al., 2016;

Hinshaw & Atwood, 1984). To this study, we assume that employees who perceive narcissistic leadership will be more likely to leave the organization.

H1: Narcissistic leadership is positively related to employees’ turnover intention.

1.1.2. Mediating Role of Psychological Capital

Psychological capital can act as a mechanism that explains the relationship between narcissistic leadership and the intention to leave, i.e., explaining how the behaviors of narcissistic leaders translate into employees’ desire to leave the organization. PsyCap has emerged as a prominent construct within the area of positive organizational behavior to represent an individual’s positive psychological state of development characterized by a core set of psychological capacities (

Luthans et al., 2007;

Luthans & Youssef-Morgan, 2017). Following psychological capital theory, individuals with high PsyCap tend to exhibit higher levels of performance and well-being in the work environment. PsyCap consists of four interconnected dimensions, each contributing to the development of a positive psychological state. PsyCap comprises four interrelated dimensions, each contributing to the construction of a positive psychological state (

Luthans et al., 2004). Hope refers to having the will and strategies to achieve goals, encompassing goal-directed energy and pathways; Efficacy represents confidence in one’s ability to take on and succeed in challenging tasks; Resilience is the ability to bounce back and persevere in the face of adversity or failure; and Optimism consists of a positive outlook on future success, expecting good things to happen.

In organizational contexts, psychological capital can be affected by narcissistic leadership by reducing its effects. Research indicates that abusive behaviors from supervisors can diminish employees’ psychological capital (

Asrar-ul-Haq & Anjum, 2020;

Seo & Chung, 2019).

Research has shown that PsyCap positively relates to a variety of desirable outcomes, including job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and performance, while exhibiting negative relationships with undesirable outcomes such as turnover intentions, job stress, and anxiety (

Avey, 2014;

Avey et al., 2011;

Shah et al., 2019;

Youssef & Luthans, 2012). Studies indicate that employees who possess greater psychological capital are more inclined to remain in their jobs and organizations instead of leaving (

Luthans et al., 2004). In addition, employees who cultivate feelings of hope, optimism, resilience, and self-efficacy demonstrate greater confidence in overcoming workplace challenges, making them more likely to remain with their organizations (

Karatepe & Karadas, 2014;

Yan et al., 2021). Furthermore, psychological capital has been found to be negatively associated with turnover intention (

Abukhalifa et al., 2023;

Çelik, 2018;

Nasria et al., 2019;

Zambrano-Chumo & Guevara, 2024;

Zhao & Gao, 2014). Several studies found a negative relationship between levels of PsyCap and the intention to leave the job, indicating that individuals with higher PsyCap are less likely to leave their jobs compared to those with lower PsyCap (e.g.,

Arora & Dhiman, 2020;

Dhiman & Arora, 2018). Also,

Singh and Randhawa (

2024) found a significant negative effect of self-efficacy on turnover intention. Employees with high self-efficacy tend to have greater confidence in their abilities, and when they perceive that the organization does not provide adequate support, they may decide to seek out better opportunities.

Concluding, PsyCap can play a fundamental role in strengthening the relationships between leaders and subordinates. Research suggested that employees with a higher PsyCap tend to feel more satisfied with both their job and their leaders and are less likely to leave their organization, which highlights the positive impact of psychological capital on retention intention. However, narcissistic leadership, as a job demand, can decrease employees’ psychological capital and, consequently, contribute to their intention to leave the organization. When exposed to such demands, employees tend to expend more psychological energy trying to cope, which can lead to the depletion of their resources, which in turn could contribute to their intention to leave the organization. As a result, narcissistic leadership can have a negative impact on employees’ PsyCap (i.e., diminishing self-efficacy, resilience, hope, or optimism), which can lead to an increase in turnover intention.

Figure 1 presents the hypothetical model.

H2: Employees’ psychological capital mediates the relationship employees’ narcissistic leadership and their turnover intention.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Participants were 266 workers from Portuguese organizations, aged between 18 and 53 years old (M = 29.13; SD = 7.53), and their average organizational tenure was 3.21 years (SD = 4.64). Most of the participants were women (62%), Regarding educational level, the largest proportion of participants completed the bachelor’s degree (41.8%), followed by those that held a master’s/postgraduate degree (29.1%). Smaller proportions of the sample had a bachelor’s degree in progress (9.2%), completed secondary education (14.9%), had basic education (1.8%), or reported other educational qualifications (3.2%). Concerning employment status, most participants had a permanent employment contract (46.1%), followed by fixed-term contracts (22.7%). Smaller proportions of the sample were on indefinite-term contracts (19.5%), part-time contracts (3.9%), internships (3.2%), or other types of employment arrangements (4.6%). Participants represented a variety of organizational sectors. The most represented sectors were Accommodation and Food Service Activities (29.1%) and “Other” (27.7%), which encompassed activities not specified in the previous categories. The remaining sectors each represented less than 12% of the sample. For a clearer overview, these sectors were grouped into the three main economic sectors: Primary, Secondary, and Tertiary, in accordance with the Portuguese Classification of Economic Activities, which is harmonized with the Statistical Classification of Economic Activities in the European Community. The distribution of participants across the main economic sectors reveals a clear predominance of the Tertiary sector (85.1%), which includes activities such as Commerce, Accommodation and Food Service Activities, Transportation and Storage, Education, Information and Communication Technology, and the ‘Other’ category.

2.2. Procedure

This study used a quantitative cross-sectional research design, employing a non-probabilistic convenience sampling approach and a self-administered questionnaire for data collection. Information was obtained from two main sources: organizational environments and informal networks. In organizational settings, the procedure began with an email sent to organizations, including a cover letter that provided a comprehensive explanation of the study’s purpose, the variables under examination, and the steps involved in the data collection process. Once the organizations agreed to participate, further instructions were shared, and employees were given access to an online questionnaire for completion. In the case of informal networks, participants were contacted through various channels, such as direct email, social media platforms (e.g., Facebook, Instagram, and LinkedIn), and face-to-face interactions. The questionnaire was hosted and distributed via Google Forms in all instances, between March and December 2024. The research received approval from the Ethics Committee of the University of Maia. Participants were informed about the study’s purpose, and ethical principles were upheld, including voluntary participation, informed consent, anonymity, and confidentiality of responses. Additionally, it was clarified that the data collected would be exclusively used for research purposes, ensuring compliance with ethical research standards.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Narcissistic Leadership

The five items of the subscale of Narcissism (e.g., “Has a sense of personal entitlement”) of the Toxic Leadership Scale were used. The original version of the scale was developed by

Schmidt (

2008), and we used the Portuguese version which was validated and translated by

Mónico et al. (

2019). This version contains 30 items; each rated on a six-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 6 (Strongly Agree). Higher scores indicate a greater perceived prevalence of narcissistic leadership behaviors.

The subscale of Narcissism exhibits Cronbach’s alpha of 0.95 in the present study’s sample. Since the modification indices suggested indications for the model improvement, covariances between the errors of items 14 and 18 were added. The measurement model yielded a good fit to the data,

χ2(4) = 11.76,

p < 0.05;

χ2/df = 2.94; GFI = 0.98; CFI = 0.99; RMSEA = 0.086. Based on suggested cut-off values, good model fit is associated with a small and significant

χ2, values around 0.90 for GFI and CFI and RMSEA below 0.10 (

Byrne, 2010).

2.3.2. Psychological Capital

Psychological capital was measured using the Portuguese version of the Psychological Capital Questionnaire (PCQ;

Luthans et al., 2007). Permission to use the instrument was granted by Mind Garden. This scale consists of 24 items distributed across four dimensions (Self-efficacy, Hope, Resilience and Optimism) each containing six specific items. Examples of sample items are: “I feel confident analyzing a long-term problem to find a solution; If I should find myself in a jam at work, I could think of many ways to get out of it; and When I have a setback at work, I have trouble recovering from it, moving on”. All items have a rating of six points on the Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree; 6 = Strongly Agree). All the subscales show good internal consistency values with Cronbach’s α values of 0.88 (Optimism), 0.91 (Resilience), 0.95 (Hope), and 0.88 (Self-efficacy). To assess scale construct validity, the multidimensionality of the measure was tested through confirmatory analysis and maximum likelihood procedure. The four-factor measurement model yielded a suitable fit to the data,

χ2(242) = 721.70,

p < 0.001;

χ2/df = 2.98; GFI = 0.82; CFI = 0.94; RMSEA = 0.086, after adding covariances between error of four pairs of items belonging to the same subscale (i.e., between items 4 and 6, items10 and 12, items 19 and 22 and items 20 and 23).

2.3.3. Turnover Intention

To assess participants’ turnover intention, the Portuguese version of the Anticipated Turnover Scale (

Hinshaw & Atwood, 1984), adapted and validated for the Portuguese population by

de Sul and Lucas (

2020), was used. The scale consists of 10 items using a seven-point Likert-type multiple-choice response format (1 = Strongly Disagree to 7 = Strongly Agree). One example of an item is “I am almost certain that I will leave my job in the near future.”. Higher scores on this scale indicate greater intention of the individual to leave the organization. A confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to assess the adequacy of the one-dimension solution of the measure. Items 6 and 9 presented very low standardized estimates (i.e., 0.07 and 0.02, respectively). These two items also had the lowest values of

R2 (i.e., 0.04 and 0.00, respectively). Consequently, items 6 and 9 were excluded from the scale. Afterwards, findings showed an acceptable model fit,

χ2(17) = 58.16,

p < 0.001;

χ2/df = 3.42; GFI = 0.95; CFI = 0.97; RMSEA = 0.96, after adding covariances between the errors of items 2, 4, and 10. Cronbach’s alpha value obtained in the present study’s sample was 0.86.

2.4. Statistical Analysis Plan

Data analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 29). Prior to main analysis, the assumptions of normality were evaluated. The internal consistency reliability of the data collection instrument was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha. Descriptive statistics, including means and standard deviations, were calculated for all variables. Correlations among the three constructs were examined using Pearson coefficient. Mediation analysis was conducted using the PROCESS macro for SPSS (version 4.1;

Hayes, 2022), employing a bootstrapping procedure with 10,000 resamples to assess the significance of the indirect effect of narcissism on turnover intention via psychological capital dimensions.

3. Results

Descriptive statistics and the Pearson correlation coefficients for all study variables are presented in

Table 1. The mean score for turnover intention was 4.23 (

SD = 1.53), indicating a moderate level of intent to leave. Narcissistic leadership had a mean of 3.03 (

SD = 1.52), suggesting medium levels of perceived narcissism in leader’s behaviors and attitudes. The four subscales of PsyCap also showed moderate mean scores, ranging from 3.63 (

SD = 1.20) for Optimism to 3.94 (

SD = 1.41) for Self-efficacy. The mean tenure at their respective companies was 3.21 years (

SD = 4.64). Turnover intention was positively and significantly correlated with narcissistic leadership (

r = 0.40,

p < 0.001) and negatively and significantly correlated with all four dimensions of PsyCap: self-efficacy (

r = −0.52,

p < 0.001), hope (

r = −0.51,

p < 0.001), resilience (

r = −0.48,

p < 0.001), optimism (

r = −0.38,

p < 0.001), and organizational tenure (

r = −0.18,

p = 0.003). Narcissistic leadership was also negatively and significantly correlated with all four PsyCap dimensions (r values ranged from −0.22 to −0.26, all with

p < 0.001). Additionally, tenure was also positively and significantly correlated with self-efficacy (

r = 0.14,

p = 0.018) and resilience (

r = 0.15,

p = 0.017).

The study employed the PROCESS macro (version 4.1;

Hayes, 2022) to investigate the hypothesized relationships between narcissistic leadership, PsyCap (i.e., self-efficacy, hope, resilience and optimism) and turnover intention, while controlling organizational tenure. Model 4 of the PROCESS macro was used to assess whether PsyCap dimensions mediated the relationship between narcissist leadership and turnover intention.

3.1. Effect of Narcissistic Leadership on Psychological Capital

The regression analysis showed that narcissistic leadership significantly predicted all the psychological capital dimensions, controlling for tenure, i.e., Self-efficacy, R2 = 0.07 (7%), F (2, 263) = 10.02, p < 0.001, B = −0.21, p < 0.001, Hope, R2 = 0.07 (7%), F (2, 263) = 10.62, p < 0.001, B = −0.23, p < 0.001, Resilience, R2 = 0.08 (8%), F (2, 263) = 11.17, p < 0.001, B = −0.20, p < 0.001, and Optimism, R2 = 0.05 (5%), F (2, 263) = 7.51, p < 0.001, B = −0.18, p < 0.001. The negative B coefficients obtained indicate that higher narcissism was associated with lower psychological levels of each of the four dimensions of PsyCap.

3.2. Effects of Narcissistic Leadership and Psychological Capital on Turnover Intention

Table 2 shows the direct effects of narcissistic leadership and PsyCap dimensions on turnover intention, controlling for organizational tenure, accounting for 39% of the variance. The regression model demonstrated narcissistic leadership (

B = 0.30,

p < 0.001), self-efficacy (

B = −0.27,

p = 0.04), and optimism (

B = 0.37,

p = 0.009) significantly predicted turnover intention. Narcissistic leadership and optimism were positively associated with turnover intention, while self-efficacy showed a negative relationship. Contrastingly, hope and resilience were not significant predictors in this model.

3.3. Total and Indirect Effects

To test the mediating effects of PsyCap dimensions on the relationship between narcissistic leadership on turnover intention, a resampling bootstrapping procedure and 10,000 samples were used for indirect confidence intervals (

Hayes, 2022). The results presented in

Table 3 show that the total effect of narcissistic leadership on turnover intention (

B = 0.41,

p < 0.001) was partially mediated by PsyCap dimensions, controlling for organizational tenure. The results presented in

Table 3 revealed that the total indirect effect of narcissism on turnover intention through PsyCap dimensions was significant, with a point estimate of 0.10, 95%

CI [0.047–0.175]. Considering each of the mediators separately, only the indirect effects via self-efficacy and optimism were significant, with point estimates of 0.06, 95%

CI [0.002–0.128] and–0.07, 95%

CI [−0.142–0.008], respectively. In contrast, the indirect effects through hope and resilience were not significant.

4. Discussion

The purpose of the present study was to gain a better understanding of the relation between narcissistic leadership and employees’ turnover intention, focusing on the mediating role of PsyCap. Specifically, examining the ways in which the behaviors and attitudes of narcissistic leaders may influence the mental state of employees and whether this leads to their desire to leave the organization provides valuable insights.

The results totally supported Hypothesis 1 because narcissistic leadership was positively associated with turnover intention. This finding corroborates the previous literature that points to the harmful consequences of dysfunctional leadership styles on the well-being of subordinates and, consequently, on their predisposition to leave the organization (e.g.,

Van Gerven et al., 2022;

Yousif & Loukil, 2022). The intrinsically self-centered nature of the narcissistic leader, involving admiration-seeking, interpersonal exploitation, lack of empathy and abusive behavior, could create a work environment perceived as toxic and draining. This result highlights the critical importance of organizations recognizing and mitigating narcissistic behaviors in their leadership teams, given the high costs associated with staff turnover and the degradation of human capital (

Hughes, 2022).

Hypothesis 2 was partially confirmed since only the indirect effects via self-efficacy and optimism were significant. This finding helps us understand the psychological mechanisms by which narcissistic leadership influences employees’ decisions to stay or leave an organization. First, self-efficacy emerged as a mediator of the relationship between narcissistic leadership and turnover intention. This result suggests that narcissistic leadership behaviors directly impact individuals’ belief in their own abilities and competencies to perform tasks and achieve goals (e.g.,

Seo & Chung, 2019) and the decrease in perceived self-efficacy acts as a predictor of exit intention. Thus, when employees are feeling less capable and valued, they might seek environments where their competences may be recognized and where they feel they can effectively contribute to their jobs and organization. These findings are in line with JD-R model (

Bakker et al., 2023) because an individual’s capacity to cope with demanding job conditions can be severely reduced when work expectations are high and, contrastingly, personal resources, including self-efficacy, are undermined. This may result in a sense of powerlessness and, consequently, the pursuit of a work environment where one’s abilities can be recognized and valued.

Second, the importance of optimism as a mediator suggests that narcissistic leadership may have a detrimental effect on workers’ perspective on the future, which may reduce their intention to leave the job. Although optimism is shown to have an important role as a mediator, the respective positive association with turnover found in the present study, when controlling for the other PsyCap dimensions and tenure, contradicted the research (e.g.,

Arora & Dhiman, 2020;

Dhiman & Arora, 2018). Nonetheless, we can presume that the decrease in optimism may be positively associated with psychological distress. For example,

Santos et al. (

2022) found that reduced optimism was related to maladaptive coping and depression in a sample of Portuguese workers of different sectors. Thus, mental distress caused by a narcissistic leader may lead employees to get less motivated to change their lives and to comply more easily with their current working conditions. Contrastingly, when the leader shows less narcissistic attitudes, subordinates tend to be more optimistic and then consider more frequently leaving the job. In this situation, employee optimism can serve as a personal resource that motivates proactive action where leaving is seen as an adaptable option to protect wellbeing and pursue a more promising professional future.

Finally, the absence of significant mediating effects through hope and resilience, contrary to what was expected for the PsyCap dimensions, suggests that these variables may not be operating as mediators in the specific context of this relationship or that their influence may be more complex. It is possible that, in the face of narcissistic leadership, hope (the ability to set goals and work toward them) and resilience (the ability to recover from adversity) are directly affected, so that their relationship with intention to leave is not linearly mediated by narcissistic behaviors, or that other mechanisms (e.g., external coping factors) become more prominent. Future research should delve deeper into the nuances of each PsyCap component in this context.

In summary, these findings not only support the idea that narcissistic leadership is detrimental, but they also help us comprehend the psychological processes by which these effects manifest. The identification of self-efficacy and optimism as mediators between the narcissistic leadership and the intention to leave suggests the importance of developing organizational interventions aimed at strengthening these psychological resources, which may lessen the effects of dysfunctional leadership and encourage the retention of talent.

4.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

This study contributes to literature in several ways. Theoretically, it deepens the understanding of the mechanism underlying the relationship between narcissistic leadership and turnover intention, offering a robust explanatory model. By demonstrating that self-efficacy and optimism, as components of PsyCap, mediate this relationship, the study contributes to understanding the mechanisms by which narcissistic leadership may influence the turnover intention. Additionally, it integrates the JD-R Theory in the analysis of narcissistic leadership, conceptualizing it as a requirement of the job and providing a solid theoretical framework to comprehend the processes of exhaustion and use of personal resources. Second, the study integrates constructs from positive psychology, namely PsyCap, with literature on dysfunctional leadership (narcissism) and turnover behavior, contributing to addressing an empirical and conceptual gap in our understanding of the relationship between individual psychological resources and negative characteristics of leadership. Finally, the study contributes to the refinement of leadership framework, particularly regarding the effects of leaders’ personality traits on employees’ attitudes and behaviors. By establishing that leader narcissism relates to subordinates’ own psychological resources, the work provides a viewpoint on the psychological and behavioral impacts of leadership. The observation that optimism may be positively associated with intention to leave in narcissistic leadership contexts represents a theoretical contribution that challenges previous assumptions about the protective role of this resource, suggesting an empowering function for proactivity in unfavorable environments.

The present study has also some practical implications for human resource management, organizations and professionals. First, the results reiterate the need for organizations to develop mechanisms to identify, prevent, and intervene in narcissistic leadership behaviors. Feedback programs, performance assessments that take into account the influence on team well-being, and specific leadership training on healthy management styles can all help to reduce work environments that may lead to turnover (e.g.,

Wu et al., 2021). Second, mediation through self-efficacy and optimism underlines the strategic importance of organizations investing in the development of their employees’ psychological capital. Organizations should take a proactive approach, focusing on building a psychologically resilient workforce. Indeed, the development of coaching, mentoring, skills training and initiatives that promote autonomy and recognition can strengthen the self-efficacy of individuals. By enhancing employee self-efficacy, companies can lessen the negative effects of more challenging environments, thereby reducing turnover intention (e.g.,

Kelloway et al., 2023). Additionally, leaders, managers, and organizations could improve employee motivation by encouraging an optimistic outlook on the future. Organizations can then avoid incurring high costs as research suggests that workers who are less motivated at work reveal higher levels of sickness absenteeism and presenteeism (

Aronsson et al., 2021) and a loss of productivity (

Lohela-Karlsson et al., 2022). However, those with a propensity for optimism may overestimate the likelihood of favorable events while underestimating the likelihood of unfavorable ones, which could be detrimental to people, especially if that optimism is unrealistic, leading to high-risk actions or further disappointment (

Purol & Chopik, 2021). Therefore, when managers notice that their more optimistic collaborators are considering leaving the organization, they should appropriately evaluate their expectations regarding the likelihood of better opportunities outside the company, provide them with accurate information about the job market, and also discuss with them potential benefits that could persuade them to reconsider their intention to leave.

In summary, the findings reinforce the interconnection between leadership dynamics, psychological well-being, and withdrawal behaviors. Thus, organizations must integrate psychological well-being management as a part of their HR strategies, creating a culture that values and protects the mental health of their employees.

4.2. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

The present study has inherent limitations that should be considered in future investigations. A primary limitation of the study lies in its cross-sectional design. Collecting data at a single point in time prevents the establishment of direct causal relationships between variables. While mediation and analysis suggest a causal pathway, we cannot say with certainty that narcissistic leadership causes the decrease in PsyCap, which in turn influences turnover intention. Future investigations should employ longitudinal designs to better capture the temporal dynamics and directionality of the relationships. The non-probabilistic and predominantly female sample from a single country limits the generalization of the results, suggesting replication in more diverse and cross-cultural samples. In addition, the exclusive reliance on self-report measures can introduce biases, so the use of multiple data sources (e.g., objective data) and mixed methods in future research is recommended. In addition to the methodological limitations, the study focused only on narcissistic leadership. Comparative exploration with other dysfunctional leadership styles is proposed, as well as the analysis of other mediators and moderators (e.g., social support, organizational culture, demographic variables) for a more complete understanding of the complex dynamics suggested by the results. Deepening the specific role of hope and resilience, which have not emerged as meaningful mediators in this context, can also be an important avenue.

5. Conclusions

This study emphasizes how psychological capital plays a dual function in the relationship between narcissistic leadership and turnover intention. Narcissistic leaders can lead to a decrease in optimism of employees, contributing to keeping them in the organization, probably demotivated. On the other hand, a narcissistic leader may cause workers to feel less confident in themselves and more inclined to leave the organization, most likely in pursuit of better opportunities. Therefore, organizations should go beyond performance assessments and actively promote the mental health of their workforce. Maintaining organizational health and reducing the risks of narcissistic leadership require promoting the full range of psychological resources. Training programs should prepare leaders not only to boost employees’ self-efficacy, but also to maintain collective optimism, ensuring that individual confidence does not turn into a greater desire to quit.

In conclusion, this study goes deeper into the topic of narcissistic leadership, emphasizing the importance of employee psychological capital in the workplace. Its theoretical and practical contributions emphasize the importance of conscious leadership management and planned investment in employees’ psychological resources to ensure long-term organizational viability.