Abstract

This study examines how the organizational work climate shapes the effectiveness of supervision on employee performance. While traditional management theory assumes supervision universally enhances productivity, we observe a puzzling paradox: facing identical tasks and wage systems, some firms rely heavily on hierarchical supervision while others thrive with minimal oversight. Through a four-month field experiment across two Chinese agricultural enterprises (5851 observations), we test whether the supervision’s effectiveness depends on the alignment between leadership practices and organizational climate. In formal management firms (FMFs) characterized by hierarchical governance and arm’s-length employment relationships, directive supervision significantly reduces task completion times by 0.126 standard deviations, equivalent to approximately 4.3 s or 2.8% of the average completion time, with this effect remaining stable throughout the workday. Conversely, in network-embedded firms (NEFs) operating through trust-based relational contracts and social norms, identical supervisory practices yield no performance gains, as informal social control mechanisms already ensure high effort levels, rendering formal supervision redundant. These findings challenge the “best practices” paradigm in strategic HRM, demonstrating that HR success requires a careful alignment between leadership approaches and the organizational climate—an effective HR strategy is not about implementing standardized practices but about achieving a strategic fit between supervisory leadership styles and existing work climates. This climate–leadership partnership is essential for optimizing both employee performance and organizational success.

1. Introduction

Supervision, a cornerstone of management theory since Taylor (Taylor, 1911), presents a fundamental paradox in organizational practice. While agency theory predicts universal performance benefits from monitoring (Eisenhardt, 1989; Jensen & Meckling, 2019), and motivation crowding theory warns of universal motivational costs (Frey & Jegen, 2001; Gagné & Deci, 2005), field evidence reveals both dramatic successes and failures across organizations facing identical market conditions. This contradiction remains unresolved in existing theories and questions strategic HRM’s pursuit of universal “best practices” (Delery & Doty, 1996; Huselid, 1995).

Empirical evidence deepens rather than resolves this puzzle. Recent field experiments document supervision’s benefits: electronic monitoring increased productivity in manufacturing settings (Pierce et al., 2015), real-time observation improved compliance behaviors in healthcare contexts, (Staats et al., 2017), and supervisory feedback enhanced operational efficiency in aviation contexts (Gosnell et al., 2020). Yet equally rigorous studies reveal supervision’s costs: monitoring markedly reduced effort when perceived as signaling distrust (Falk & Kosfeld, 2006), digital surveillance diminished creative performance in remote work settings (Belot & Schröder, 2016), and observation crowded out prosocial behavior in charitable organizations (Jeworrek & Mertins, 2022). These contradictory findings suggest the need for theoretical reconciliation.

Three important gaps limit our understanding. First, while research examines surface-level moderators like task complexity (Holmstrom & Milgrom, 1991) or technology (Bloom & Van Reenen, 2011), it overlooks how deep organizational structures—specifically configurations of formal governance and informal social mechanisms—may shape supervision’s effectiveness (Ostrom, 1990; Williamson, 1991). Second, we lack an understanding of when supervision aligns with organizational justice expectations versus violating implicit psychological contracts (Rousseau, 1995; Tyler & Blader, 2003). Third, existing research fails to explain how supervision interacts with existing governance mechanisms—whether creating institutional complementarity or redundancy—leaving us unclear when supervision enhances versus disrupts organizational functioning (Bowles, 2008). Without a framework explaining these contingencies, organizations risk implementing supervision that wastes resources or disrupts existing governance equilibria (Putnam, 2000).

Addressing these gaps requires comparing supervision effects across fundamentally different organizational climates while holding other factors constant—a challenge given that organizations typically differ along multiple dimensions. China’s agricultural modernization provides an ideal empirical setting. The sector’s rapid transformation has produced two distinct yet equally viable organizational forms operating under identical market conditions and wage systems (Kung, 2002; Nee, 1992). Formal management firms (FMFs), established by external capital, transplant corporate governance through hierarchical supervision and arm’s-length employment contracts (Walder, 1995). Network-embedded firms (NEFs), evolved from local growers, operate through trust-based relational contracts with minimal formal oversight, leveraging dense community ties for behavioral regulation (Bian, 1997; Peng, 2004). Both forms demonstrate sustained profitability despite contrasting supervisory approaches, offering a natural variation to test how the organizational context shapes management effectiveness.

Through a four-month field experiment across these contexts (5851 observations), we address two questions central to strategic HRM. First, can supervision enhance performance under fixed-wage systems where monetary incentives are separate from output—a prevalent condition in modern employment (Lazear, 2000)? Second, does the organizational form systematically moderate supervision’s effectiveness? Our identification leverages exogenous variation in supervision timing and randomized worker pairings, with high-dimensional fixed effects controlling for confounding factors (Angrist & Pischke, 2009).

Results suggest supervision’s effectiveness appears contingent on organizational alignment. In FMFs, directive supervision reduces task completion time by 0.126 standard deviations (approximately 4.3 s or 2.8% improvement) (p < 0.01), with effects remaining stable across the workday. In NEFs, identical practices yield null effects—informal social mechanisms already ensure high effort, rendering formal supervision redundant. These findings demonstrate that even basic management tools require an organizational fit: supervision complements hierarchical governance but proves ineffective where social norms provide behavioral regulation (Coleman, 1988; Granovetter, 1985).

This study contributes to theory in three ways. First, we establish organizational governance as a boundary condition for supervision effectiveness, bridging organizational and behavioral perspectives (House et al., 1995). Second, we demonstrate that formal and informal governance operate as institutional complements rather than substitutes (Aoki, 2001; Milgrom & Roberts, 1995). Third, we show that supervision’s temporal dynamics depend on the organizational fit, challenging assumptions about universal intervention decay (Kolstad, 2013; Nagin et al., 2002). Practically, our findings suggest that HR effectiveness may benefit from matching the supervision to the organizational context—directive oversight enhances performance in formal hierarchies but wastes resources in relational contexts. This contingent approach offers one potential explanation for why identical practices produce divergent outcomes and may inform context-specific management design.

2. Theoretical Framework

The contradictory findings on supervision effectiveness suggest that contextual factors fundamentally shape how employees respond to oversight. Organizational justice theory offers a lens for understanding this variation: employees’ reactions to management practices depend on whether these practices align with prevailing fairness norms (Greenberg, 1987; Tyler & Blader, 2003). In formal organizations with bureaucratic governance, directive supervision may be perceived as a legitimate authority, ensuring a fair contribution. In relational organizations built on trust and reciprocity, identical supervision might violate implicit social contracts and signal unwarranted distrust (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005).

This justice perspective suggests that supervision’s effectiveness depends not merely on its implementation but on its perceived legitimacy within organizational contexts. While we do not directly measure justice perceptions, the distinct organizational forms in our study—formal management versus network-embedded—likely embody different fairness frameworks that shape supervision’s impact. We now develop specific predictions about how these organizational contexts moderate supervision effectiveness.

2.1. Control Theory Perspective and Formal Organizations

The organizational justice perspective suggests that supervision effectiveness may depend on an alignment with fairness norms. In formal management firms, this alignment appears particularly strong—hierarchical oversight fits naturally within bureaucratic structures where systematic monitoring is expected rather than resented.

Control theory posits that supervision addresses effort provision problems under fixed wages by making shirking observable and creating accountability pressure (Nagin et al., 2002). However, these mechanisms require enabling conditions. FMFs provide three such conditions: First, explicit employment contracts establish clear authority relationships, placing supervision within employees’ “zone of acceptance (Simon, 2013)”. Second, formal hierarchies make supervisory observations consequential for employment outcomes, unlike settings where social relationships buffer such decisions (Williamson, 1975). Third, the absence of dense social networks eliminates alternative governance through peer monitoring or reputation, making formal supervision necessary rather than redundant (Kandel & Lazear, 1992).

Empirical evidence supports these predictions in comparable formal settings. Pierce et al. found that monitoring systems reduced theft and increased productivity in hierarchical service environments, with gains driven by behavioral changes in existing employees rather than staff turnover (Pierce et al., 2015). Staats et al. demonstrated that supervision improved compliance in bureaucratic healthcare settings (Staats et al., 2017). These effects emerged specifically where formal structures legitimized oversight and informal governance was weak.

This convergence suggests supervision in FMFs operates as an institutionally embedded mechanism rather than an external imposition. When supervision aligns with justice norms, operates through legitimate authority, and fills governance voids, it should enhance performance through institutional complementarity—each formal element reinforcing rather than undermining the others (Milgrom & Roberts, 1990). Therefore,

H1.

In formal management firms (FMFs), a managerial presence will significantly reduce the time employees require to complete a unit of work.

2.2. Relational Governance and Network-Embedded Organizations

In network-embedded firms, supervision operates within a fundamentally different institutional logic—one where relational justice norms and social governance mechanisms predominate (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005). Unlike the procedural justice emphasis in bureaucratic settings, NEFs operate through relational justice principles emphasizing trust, reciprocity, and mutual respect (Blader & Tyler, 2009).

In these contexts, formal supervision may violate implicit fairness expectations in three ways. First, it signals distrust where trust-based relationships are the norm, potentially breaching psychological contracts built on mutual confidence (Rousseau, 1995). Second, it imposes hierarchical observation in settings where authority derives from social standings rather than formal positions (Granovetter, 1985). Third, it introduces an external control where self-regulation through internalized norms and peer accountability already ensures high effort (Ostrom, 1990).

Self-determination theory provides the psychological mechanism underlying these violations. When supervision threatens autonomy in contexts where self-governance is expected, it triggers particularly strong crowding-out effects (Deci & Ryan, 2000). Recent evidence confirms this pattern: Falk and Kosfeld found that monitoring reduced effort by 30%, specifically when perceived as violating trust norms (Falk & Kosfeld, 2006).

Moreover, NEFs’ dense social networks provide comprehensive behavioral regulation through multiple channels: reputation mechanisms within tight-knit communities (Coleman, 1988), mutual monitoring among workers who are often neighbors (Bandiera et al., 2005), and internalized norms from long-term socialization (Arnott & Stiglitz, 1991). These mechanisms operate continuously and organically, making formal supervision not merely unnecessary but potentially disruptive to the established social equilibrium.

Empirical evidence supports this institutional redundancy. In settings with strong social capital, external monitoring often fails to improve and may even harm performance. Dickinson and Villeval demonstrated that supervision had no effect in high-trust environments where reciprocity norms already motivated effort (Dickinson & Villeval, 2008). More tellingly, Bowles and Polania-Reyes found that formal incentives can “demoralize” socially motivated behavior, particularly in communities with strong social cohesion (Bowles & Polania-Reyes, 2012). Therefore,

H2.

In network-embedded firms (NEFs), a managerial presence will have no significant effect on the time employees require to complete a unit of work.

2.3. Time-Varying Effects Across Organizational Contexts

The temporal dynamics of supervision—whether its effects persist or fluctuate during the workday—may depend fundamentally on the organizational context rather than universal psychological processes.

In formal management firms, supervision constitutes an institutionalized practice embedded within daily organizational routines. Three factors promote this stability. First is routine integration: supervision in FMFs follows predictable patterns, scheduled intervals, and standardized procedures that workers internalize as the normal workflow (Pentland & Feldman, 2005). Second is consistent enforcement: unlike one-time interventions, supervision in FMFs carries persistent consequences for performance evaluations and employment decisions, maintaining its motivational relevance throughout the workday (Nagin et al., 2002). Third is the absence of collective resistance: in FMFs’ individualized employment relationships, workers lack the social coordination necessary to develop shared coping strategies that might erode supervision’s effectiveness over time (Hollander & Einwohner, 2004).

The empirical evidence supports institutional persistence. Bloom et al. found that management practices embedded in organizational systems maintained effectiveness over multiple years, while isolated interventions typically showed substantial decay within months (Bloom et al., 2015). In manufacturing settings similar to our FMFs, Bernstein documented stable monitoring effects across five-month periods when supervision was integrated into production routines (Bernstein, 2012). The key distinction lies not in the practice itself but in its institutional embeddedness—whether workers experience it as an exceptional intervention or a standard operating procedure. Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

H3a.

In formal management firms, supervision’s positive impact on employee performance remains stable throughout the workday, without significant temporal decay.

In network-embedded firms, the temporal dynamics differ fundamentally—not because supervision effects decay but because they never meaningfully materialize. Social control mechanisms in NEFs operate continuously through overlapping channels: mutual observation among workers who are often neighbors, reputation concerns within tight-knit communities, and internalized norms from long-term socialization (Coleman, 1988; Ostrom, 1990). These mechanisms function independently of formal supervision, maintaining consistent effort levels through social rather than hierarchical pressure.

Importantly, even during periods when individual self-control might wane—such as afternoon fatigue—collective mechanisms compensate. Bandiera et al. demonstrated that workers in socially connected teams maintain steady productivity throughout the day, as peer presence substitutes for individual discipline (Bandiera et al., 2005). When formal supervision briefly enters this environment, it neither enhances these existing mechanisms nor disrupts them sufficiently to alter established patterns. The social equilibrium quickly reasserts itself, rendering the supervisory presence inconsequential at any time point. Therefore,

H3b.

In network-embedded firms, managerial presence will have no significant effect on employee performance at any time point during the workday.

3. Experimental Design and Data

3.1. The Experimental Setting

We conducted a four-month field experiment from December 2023 to April 2024 in two floriculture enterprises in China. Controlled-environment floriculture provides an ideal experimental setting for three reasons. First, production tasks are highly standardized and repeatable, enabling precise productivity measurements. Second, the enclosed greenhouse environment isolates the work from external shocks while creating controlled conditions for observing supervision effects. Third, the industry’s prevalent fixed-wage system (100 RMB/day) eliminates confounding from output-based incentives.

The spatial layout of greenhouses creates natural conditions for both peer interactions and supervision. Narrow aisles (0.8–1.2 m) force workers into close proximity during peak periods, allowing us to observe how management presence affects productivity in realistic work environments. This arrangement is determined by production requirements rather than the experimental design, ensuring natural worker behavior.

We employed purposive sampling to select two firms representing the organizational dualism characteristic of China’s agricultural transformation: formal management firms (FMFs) with hierarchical structures and network-embedded firms (NEFs) operating through social networks. Rather than seeking statistical representativeness, we prioritized internal validity by studying these archetypal firms in controlled settings, enabling clear identification of causal mechanisms—a primary advantage of field experiments (List, 2007).

ZY Company exemplifies the formal management model with transplanted corporate practices and hierarchical employer–employee relationships. BS Company represents the network-embedded model, operating through dense social ties and informal agreements evolved from local grower networks. Table 1 systematically compares their organizational characteristics, revealing similarities in wages, workforce composition, and tasks that facilitate controlled comparison.

Table 1.

Comparison of firm characteristics.

3.2. Intervention and Randomization

Identifying causal supervision effects requires addressing two endogeneity concerns: non-random worker pairing and endogenous managerial presence. Our research design combines experimental intervention with natural variation in production schedules to generate exogenous variation in both of these dimensions.

To mitigate endogenous grouping and ensure the exogeneity of worker pairings, we implemented a structured randomization protocol in collaboration with firm managers. The protocol included (1) maintaining pairing records to ensure each worker collaborated with at least 60% of colleagues, (2) reassigning pairs after three consecutive days together, and (3) systematically mixing workers across skill levels. This intervention method both preserved the naturalness of the production process and ensured the exogeneity of the pairings.

Managers maintained typical supervision routines without knowledge of our research objectives, ensuring natural behavior patterns. We define managerial presence as a binary variable equaling 1 when a manager was physically present within a 5 min observation window, engaged in either directive (monitoring, instructing) or participatory (demonstrating, working alongside) activities.

3.3. Data and Variable Construction

We collected data through two methods. First, we utilized pre-existing high-definition camera systems installed by management for routine oversight more than three months before our study. Pre-experimental surveys confirmed workers were accustomed to the cameras and reported no behavioral effects, mitigating Hawthorne effect concerns.

We processed video footage using computer vision algorithms to identify worker positions and actions, then segmented it into five-minute observation units—a duration capturing 2–3 work cycles while smoothing random fluctuations. Trained research assistants verified all algorithm-identified results, yielding 5851 valid worker–period observations across 93 workdays. This objective measurement approach, with managerial presence and task completion time captured through independent observational sources rather than self-reports, inherently eliminates common method bias concerns. The pre-existing camera systems, installed months prior to our study, ensured natural work behavior without reactivity effects.

Second, we collected background information on the laborers through a structured questionnaire, which covered demographics such as age, education level, and household status, as well as their work experience in controlled-environment agriculture and their personality traits.

Key variables require clarification: “time per unit of work” measures seconds to complete one standardized task unit. “Worker Ability” and “Peer Ability” are objective productivity indicators constructed econometrically from performance in other contexts (detailed in Section 4.1).

Table 2 presents descriptive statistics. The sample averages 52.16 years old with 7.01 years of education, reflecting China’s aging agricultural workforce. Experience differs markedly between firm types (10.44 vs. 148.56 months), validating our organizational categorization: FMFs rely on external labor markets while NEFs maintain stable local networks. Despite experience disparities, all workers completed tasks independently, with individual differences captured through Worker Ability measures and fixed effects.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of key variables.

4. Empirical Strategy

4.1. The Econometric Model

We identify the causal effect of supervision on worker efficiency under fixed-wage systems using the following econometric model:

where the dependent variable represents the time taken by worker to complete a unit of work in plot during observation in time period . A lower value indicates higher efficiency.

Our core explanatory variable of interest is . This variable is a dummy for the on-site presence of a manager, taking a value of 1 if a manager is physically present and 0 otherwise. As the two firm types employ different supervision models, the coefficient of this variable, , will capture the effect of directive supervision in formal management firms and participatory supervision in network-embedded firms. Our design identifies supervision effects within each organizational context rather than directly comparing supervision styles, enabling tests of organizational–supervisory complementarity.

A central challenge in this model is to disentangle the supervision effect from potential peer effects. To address the endogeneity inherent in peer interactions—often termed the “reflection problem”—we include an exogenous measure of Peer Ability, as a control (Manski, 1993). This variable is constructed using a double leave-one-out1 (DLOO) method. First, for each plot we estimate every worker’s baseline ability using only their performance data from all other plots (i.e., leaving out plot ). This yields an ability measure for each worker that is exogenous to their performance and interactions within plot . Second, to construct the Peer Ability variable for worker in plot , we take the average of the exogenous abilities of their peers (j = i) that were calculated in the first step. This ensures that the measure of Peer Ability is not contaminated by the immediate, shared experience between worker and their peers in plot .

Furthermore, the model includes a comprehensive set of controls. is a vector of control variables for worker at time , including baseline characteristics such as individual ability, personal and household attributes, psychological traits, as well as a key time-varying control variable, Immediate Workload, which measures the amount of work assigned to the worker in the current 5 min observation window. Note that Worker Ability, being time-invariant, is absorbed by the worker fixed effects μi and is therefore not included separately in models with worker fixed effects. We include this variable in the model to control for potential fatigue effects or variations in task intensity over time. represents worker fixed effects to absorb any unobserved, time-invariant heterogeneity. To account for complex, unobservable spatio-temporal factors, the model incorporates high-dimensional fixed effects (HDFEs), (plot × session × time). This term absorbs all factors common to workers at a specific point in space and time, such as the environmental conditions, crop status, or daily work intensity. By controlling for this HDFE term, we ensure that the identified variation derives from differences in worker pairings under the same spatio-temporal conditions. Our plot × session × time fixed effects structure is highly granular and controls for all time-varying factors common to workers in the same location at a specific point in time, including the environmental conditions, task difficulty, and crop status. This ensures that the identification is derived solely from the variation within these identical production contexts. Finally, is the random error term. We cluster standard errors at the worker level to account for a potential serial correlation. The random error term is assumed to be uncorrelated with the regressors conditional on the full set of fixed effects.

4.2. Endogeneity Issues and Identification Strategy

Our empirical strategy addresses two key identification challenges in estimating supervision effects. The first challenge stems from peer interactions, which can create both reflection problems and correlated effects. The second challenge is the potential for endogeneity in the managerial presence, where managers might selectively supervise based on unobserved productivity factors.

Our identification strategy relies on two key assumptions. First, we assume an exogenous peer composition, where our experimental randomization of worker pairings eliminates correlated effects, and the DLOO method addresses the reflection problem by using predetermined peer characteristics orthogonal to current interactions. Second, we assume the conditional exogeneity of supervision, whereby the managerial presence is exogenous conditional on our comprehensive fixed-effects structure. This assumption is plausible for two reasons. Managers maintained typical supervision routines without the knowledge of our research objectives, mitigating experimental demand effects. Additionally, our granular plot × session × time fixed effects absorb systematic productivity shocks that might otherwise attract managerial attention.

Table 3 validates Assumption 1 through balancing tests. Column (1) shows that workers’ characteristics do not predict Peer Ability assignments, confirming successful randomization and mitigating sorting concerns.

Table 3.

Balancing test.

5. Empirical Results

5.1. Baseline Results

Table 4 demonstrates significant differences between OLS and fixed-effects estimates, highlighting the importance of controlling for unobserved heterogeneity. The OLS estimates (Column 3) yield a significant negative coefficient for managerial presence (−0.031), suggesting initial efficiency gains from supervision. However, this likely reflects an omitted variable bias from the endogenous timing of the managerial presence. Once we control for both worker fixed effects and comprehensive spatio-temporal factors using our preferred fixed-effects specification (Column 6), the coefficient of managerial presence becomes economically small and statistically insignificant (0.022, with a p-value of 0.346).

Table 4.

Baseline regression results for individual labor efficiency.

However, the null average effect in the pooled fixed-effects sample does not imply universal supervision ineffectiveness. This null result masks the substantial heterogeneity across firm types, as predicted by our theoretical framework. To test this organizational complementarity hypothesis, specifically our Hypotheses 1 and 2, we estimate our model separately for each firm type. The results, presented in Table 5, provide strong support for this theoretical prediction.

Table 5.

A comparison of supervision effects across different enterprise types.

The findings demonstrate significant heterogeneity in supervision effects across the two firm types, strongly supporting Hypotheses 1 and 2. For formal management firms (FMFs), as presented in Column (4) of Table 5, the coefficient of managerial presence is −0.126 and is statistically significant at the 1% level. This indicates that directive supervision significantly enhances productivity in these hierarchical organizations, reducing the standardized completion time by 0.126 standard deviations, which translates to approximately 4.3 s or 2.8% of the mean task completion time. This finding supports Hypothesis 1.

In stark contrast, for network-embedded firms (NEFs), as shown in Column (2) of Table 5, the coefficient of the managerial presence is small and statistically indistinguishable from zero. In these firms, where dense social networks and relational contracts already provide strong informal enforcement mechanisms, the manager’s presence yields no discernible productivity gains. This null effect aligns with Hypothesis 2.

The insignificant average effect of supervision in the pooled sample strongly suggests the presence of underlying heterogeneity, as our framework centering on organizational complementarity predicts. We hypothesize that the effectiveness of supervision is contingent on the firm’s governance structure, with formal supervision complementing hierarchical governance but proving redundant in network-embedded firms where social mechanisms already provide effective effort incentives. To test this organizational complementarity hypothesis, we estimate our model separately for formal management and network-embedded firms. The results, presented in Table 5, provide strong support for this prediction.

The findings reveal a stark divergence in supervision effects across the two firm types. For network-embedded firms (NEFs), the coefficient of the managerial presence is small and statistically indistinguishable from zero. In these firms, where dense social networks and relational contracts already provide strong informal enforcement mechanisms, the manager’s presence—engaging in participatory supervision—yields no discernible productivity gains. This robust null effect is consistent with the hypothesis that such managerial oversight becomes redundant when effective social monitoring mechanisms are already in place, rather than providing complementary value as it does in hierarchical organizations.

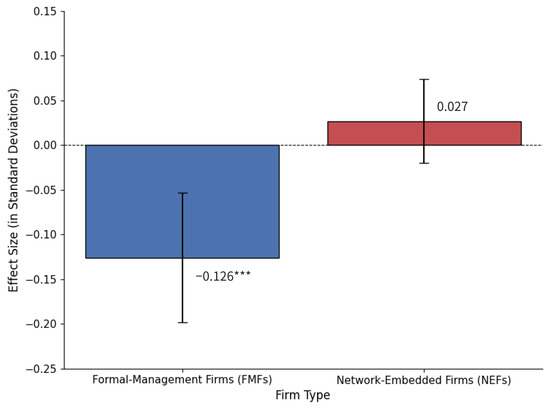

In stark contrast, for formal management firms (FMFs), the coefficient of managerial presence is −0.126 and is statistically significant at the 1% level. This indicates that directive supervision significantly enhances productivity in these hierarchical organizations, reducing the standardized completion time by 0.126 standard deviations (a 4.3 s or 2.8% improvement). This suggests that in organizational contexts characterized by arm’s-length employment relationships and formal hierarchies, directive supervision functions as an essential governance mechanism that complements the firm’s bureaucratic structure. Figure 1 visualizes the differential effects of managerial presence across organizational forms, clearly illustrating the contrasting patterns that support our hypotheses.

Figure 1.

Effect of managerial presence on task completion time by firm type. Note: Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Negative values indicate reduced task completion time (improved efficiency). *** p < 0.01.

5.2. Heterogeneity Analysis

Having established a systematic variation in supervision effects across organizational types, we test Hypotheses 3a and 3b, which concern whether these effects also exhibit temporal heterogeneity. Theory suggests supervision effectiveness may vary temporally due to fatigue, attention limitations, or strategic adaptation. To test for these dynamics, this paper combines the supervision variable with a dummy indicator for the afternoon period. The regression results in Table 6 reveal two fundamentally different and theoretically profound temporal dynamic patterns.

Table 6.

The temporal heterogeneity of the supervision effect.

In formal management firms, we find that the efficiency-enhancing effect of supervision does not decrease over the workday. The coefficient of managerial presence is −0.126 (approximately 4.3 s) (p < 0.01) in the morning, and a lincom test confirms that the effect is statistically identical in the afternoon. This temporal stability suggests that a mature, rule-based supervision system creates a persistent incentive structure. This supports Hypothesis 3a. Such a system appears robust to potential time decay factors, like worker fatigue or strategic adaptation, and thereby provides a stable backstop for productivity.

In network-embedded firms, managerial presence shows no significant effect on efficiency across time periods. However, the significant negative interaction term (coefficient = −0.076, p < 0.05) reveals that its mode of action is not static. Instead, it undergoes a significant dynamic shift from a tendency to decrease efficiency in the morning (a positive, insignificant coefficient) to a tendency to improve it in the afternoon (a negative, insignificant coefficient). This pattern corroborates the core explanation of this paper: in organizations dominated by strong endogenous social norms and relational contracts, external formal managerial intervention is redundant. The weak fluctuations it generates are insufficient to disturb the pre-existing, stable effort equilibrium. This persistent null effect aligns with Hypothesis 3b.

5.3. Robustness Checks

5.3.1. Adjusting the Fixed-Effects Specification

Our baseline specification includes plot × session × time fixed effects. For robustness, we test a coarser plot × time specification. Table 7, columns (1) and (2) show that the core results remain stable: the supervision effect remains significant in formal management firms and insignificant in network-embedded firms.

Table 7.

Robustness checks.

5.3.2. Changing the Standard Error Clustering Method

We implement two-way clustered standard errors at both worker and spatio-temporal levels to address multi-dimensional correlations. Table 7, columns (3) and (4) indicate that while the adjusted standard errors change slightly, this does not affect the conclusions of our statistical inference.

5.3.3. Excluding Extreme Observations

We exclude observations below the 5th and above the 95th percentiles to address the outlier influence. Table 7, column (5) confirms that our main findings remain significant after trimming the FMF sample. This reflects fundamental differences in ability distributions across firm types: the Worker Ability in network-embedded firms is highly homogeneous, while the ability distribution in formal management firms is more dispersed.

6. Discussion

6.1. Theoretical Implications

Our findings contribute to organizational theory by demonstrating that supervision effectiveness is contingent upon organizational governance structures, extending contingency theory beyond task and environmental factors to fundamental institutional configurations. The contrasting results—supervision significantly enhancing performance in formal management firms while showing no effect in network-embedded firms—suggest that the organizational form functions as a boundary condition that determines whether management practices activate their intended mechanisms (Donaldson, 2001).

This evidence informs contingency theory in three ways. First, it identifies the organizational governance structure as a higher-order contingency that may provide a deeper institutional context for traditional moderators such as task complexity or environmental uncertainty (Lawrence et al., 1967). While previous contingency research has accumulated numerous moderating variables, our results suggest these may be symptoms of deeper institutional differences. Second, the temporal stability of effects within each organizational type indicates that contingencies operate not through temporary situational factors but through enduring institutional logics that shape how practices are enacted and interpreted (Thornton et al., 2012). Third, the absence of supervision effects in network-embedded firms, rather than merely weakened effects, suggests that contingencies can create categorical differences in causal mechanisms rather than continuous moderation.

This study also contributes to institutional theory by providing empirical evidence for the complementarity between formal and informal governance mechanisms (Milgrom & Roberts, 1995). In formal management firms, supervision appears to function as part of an integrated system, where hierarchical authority, bureaucratic procedures, and monitoring practices mutually reinforce each other. The stability of supervision effects throughout the workday in these firms suggests that institutionalized practices may be resistant to typical fatigue or habituation effects when embedded within compatible organizational architectures. Conversely, in network-embedded firms, the null effect of supervision indicates that informal governance mechanisms—potentially including social norms, peer monitoring, and relational contracts—may constitute a well-developed alternative system rather than a partial substitute for formal control.

These findings add nuance to the theoretical foundations of strategic human resource management, particularly the assumption that management practices possess inherent technical properties that produce predictable outcomes (Delery & Doty, 1996). Our results suggest that practices may instead operate as institutional carriers whose effects depend on their alignment with prevailing organizational logics. This perspective reconciles contradictory findings in supervision research: what appears as inconsistent evidence may actually reflect consistent patterns once the organizational form is considered. The implication extends beyond supervision to suggest that the entire “best practices” paradigm may be enriched by a more context-sensitive framework of how management practices generate their effects.

Finally, our study contributes to the emerging literature on hybrid organizational forms in transitional economies (Pache & Santos, 2013; Zhou et al., 2017). The coexistence of formal management and network-embedded firms in the same industry, facing identical market conditions and production requirements, demonstrates that multiple governance configurations can be viable within a single institutional field. This finding offers a counterpoint to evolutionary perspectives that predict a convergence toward a single efficient form, suggesting instead that organizational diversity may persist when different governance structures solve coordination problems through distinct but equally effective mechanisms. The findings also imply that attempts to blend formal and informal governance—common in organizational reform efforts—may fail if they do not account for the systemic nature of these configurations.

6.2. Comparison with Previous Studies

Our findings align with and potentially help explain the mixed results in the supervision literature. Studies reporting positive supervision effects have often been conducted in formal organizational settings, though the organizational form has rarely been explicitly considered as an explanatory factor. Nagin et al. found sustained productivity gains from monitoring in call centers (Nagin et al., 2002), and Pierce et al. documented reduced theft in restaurant chains (Pierce et al., 2015)—all contexts characterized by hierarchical structures and standardized procedures. Our results in formal management firms are consistent with these findings, suggesting that formal organizational contexts may provide conditions where supervision enhances performance.

Studies reporting negative or null supervision effects have often emerged from different organizational contexts, though the role of the organizational form has seldom been theorized. Falk and Kosfeld found that monitoring reduced effort in laboratory settings designed to foster trust-based relationships (Falk & Kosfeld, 2006). Dickinson and Villeval observed motivation crowding-out in a family firm characterized by long-term employment relationships (Dickinson & Villeval, 2008). Belot and Schröder observed negative spillover effects where monitoring undermined unmonitored performance dimensions (Belot & Schröder, 2016). Our findings in network-embedded firms parallel these results, suggesting that supervision may be less effective in organizations where alternative governance mechanisms are present. However, it is important to note that these studies differ in many dimensions beyond the organizational form, including tasks, measurement approaches, and cultural contexts.

Our study contributes to this literature by explicitly comparing supervision effects across organizational forms within a controlled setting. By holding constant the industry, task requirements, compensation structure, and regional context, we can isolate the potential role of organizational governance in shaping supervision effectiveness. The continuous observation method captures temporal dynamics that survey-based studies might miss, revealing that supervision effects—whether positive or null—remain stable throughout the workday in our context. This stability contrasts with some previous findings of declining intervention effects over time (Kolstad, 2013), though differences in the setting and measurement make a direct comparison challenging.

Several limitations should be considered when comparing our results to previous studies. First, our agricultural setting may differ in important ways from the service and manufacturing contexts examined in much supervision research. Second, the Chinese institutional context, with its particular blend of formal and informal governance mechanisms, may influence how supervision operates (Nee, 1992). Third, while we interpret differences between firm types as reflecting the organizational form, other unmeasured factors could contribute to the observed patterns. Future research might examine whether similar patterns emerge in other industries and institutional contexts, using designs that can more definitively isolate the role of the organizational form in shaping supervision effectiveness.

6.3. Practical Implications

The contingent nature of supervision effectiveness revealed in our study carries important implications for management practice. The stark contrast in supervision outcomes across organizational forms suggests that practitioners should move beyond seeking universal supervisory solutions toward understanding how their specific organizational context shapes the management tool’s effectiveness.

For organizations contemplating supervision system investments, our findings indicate that expected returns depend critically on existing governance structures. In formal hierarchical organizations where bureaucratic procedures and arm’s-length employment prevail, supervision appears to offer measurable productivity gains that remain stable across time periods. However, in organizations where dense social networks and relational contracts characterize employment relationships, identical supervisory investments may yield no discernible performance benefits, as existing social governance mechanisms already regulate effort effectively. This suggests that managers should first assess whether their organizational structure creates conditions conducive to supervision effectiveness.

The findings speak particularly to organizations undergoing transformation or expansion. Enterprises scaling from local to regional operations often face pressure to formalize management systems, yet our results suggest that importing supervisory practices without corresponding changes in underlying governance structures may prove ineffective. Similarly, established corporations attempting to cultivate entrepreneurial cultures or network-based innovation ecosystems might find that maintaining traditional supervisory approaches undermines rather than supports these organizational changes. The effectiveness of the supervision appears tied not to its technical implementation but to its fit within the broader organizational architecture.

For multinational organizations operating across diverse cultural and institutional contexts, our findings suggest the need for locally adapted management approaches rather than globally standardized supervision policies. Units embedded in contexts with strong social networks and relational governance may require fundamentally different management approaches than those operating in formal, bureaucratic settings. This challenges the common practice of implementing uniform global management systems and suggests that effective international management requires sensitivity to local organizational forms.

While these implications emerge from agricultural production in China, the underlying principle—that management practice effectiveness depends on organizational governance alignment—likely extends beyond this specific context. Organizations operating in different industries or cultural settings should consider how these factors might modify but not eliminate the fundamental relationship between supervision effectiveness and organizational form. The key insight for practitioners is recognizing that successful management requires diagnosing and working within their organizational governance reality rather than imposing practices that succeed elsewhere under different organizational conditions.

7. Conclusions

The fundamental insight is that successful management depends on achieving a strategic fit between practices and organizational contexts. Through a field experiment comparing formal management and network-embedded firms in Chinese agriculture, we find that identical supervisory practices produce contrasting outcomes—enhancing performance by 0.126 standard deviations (approximately 2.8% productivity improvement) in hierarchical organizations while showing no effect in network-based firms. These results challenge the paradigm of universal best practices, suggesting instead that effectiveness derives from an alignment between practices and organizational contexts.

Our findings extend contingency theory by establishing the governance structure as a meta-level boundary condition for management practices. The temporal stability of these differential effects indicates that the organizational form creates enduring institutional logics rather than temporary situational variations. This insight reconciles contradictory findings in supervision research by revealing that identical practices may operate through fundamentally different causal regimes across organizational contexts. For practice, the implication is clear: management effectiveness requires diagnosing organizational governance before selecting supervisory approaches.

Several limitations warrant consideration. First, our focus on the task completion time cannot address potential speed–quality trade-offs. While quality safeguards ensure minimum standards, we cannot detect quality variations above the threshold. Workers under supervision might optimize within acceptable quality ranges, potentially delivering work that meets standards but lacks optimal care. Second, despite comprehensive fixed effects, endogenous managerial presence remains possible if managers systematically appear during problematic periods our five-minute windows cannot capture. Third, generalizability requires careful consideration. While our agricultural setting with routine tasks differs from dynamic or knowledge-based work, the core principle—that supervision effectiveness depends on organizational governance alignment—likely transcends industries. In manufacturing or service sectors with standardized processes and formal hierarchies, supervision should similarly enhance performance. Conversely, in creative industries with strong peer-review cultures (e.g., software teams), formal supervision may prove equally redundant as in our network-embedded firms. The key insight for practitioners is to first diagnose whether their organization operates through formal hierarchical control or informal social mechanisms before implementing supervisory systems. Though China’s institutional environment where traditional networks coexist with modern structures may produce unique patterns, the fundamental tension between formal and informal governance exists globally, suggesting our findings offer broadly applicable principles even if specific manifestations vary across contexts.

Future research should address these limitations through complementary approaches. Methodologically, randomized supervision schedules could eliminate endogeneity concerns, while lead–lag analyses could test whether productivity changes precede rather than follow managerial presence, and randomization inference could compare observed effects against placebo distributions. To examine speed–quality trade-offs, studies should incorporate multi-dimensional performance metrics capturing both efficiency and quality dimensions beyond minimum thresholds.

Theoretically, longitudinal studies following firms through organizational transitions could reveal how supervision effectiveness evolves with changing governance structures. Cross-cultural replications could test whether the supervision–governance relationship transcends institutional contexts. Laboratory experiments decomposing the monitoring intensity, social network density, and contract types could identify precise mechanisms underlying our findings.

Most importantly, emerging organizational forms warrant particular attention. Hybrid organizations that blend formal hierarchies with network-based teams present unique challenges for understanding supervision effectiveness. Similarly, digital supervision environments—where algorithmic monitoring coexists with remote work autonomy—may require entirely new theoretical frameworks to understand how traditional boundaries between control and trust are being reconfigured. These contexts could reveal whether our findings represent fundamental principles of organizational governance or are specific to traditional organizational forms. Specifically, hybrid organizations could be studied through matched-pair designs comparing units within the same firm that operate under different governance modes, while digital supervision could be examined through field experiments comparing algorithmic versus human monitoring systems, tracking performance outcomes over extended periods.

The fundamental insight remains: successful management depends on achieving a strategic fit between practices and organizational contexts. As organizations navigate evolving employment relationships and hybrid work arrangements, recognizing this context dependency becomes essential. Rather than pursuing elusive best practices, both researchers and practitioners should focus on understanding how organizational governance shapes the causal pathways through which management practices generate their effects.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.L. and X.Y.; methodology, Z.L. and X.Y.; software, Z.L.; validation, Z.L. and X.Y.; formal analysis, Z.L. and X.Y.; investigation, Z.L. and X.Y.; resources, Z.L.; data curation, Z.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.L.; writing—review and editing, Z.L. and X.Y.; visualization, Z.L. and X.Y.; supervision, X.Y.; project administration, X.Y.; funding acquisition, X.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Shenyang Agricultural University (IRB approval number: SYAU202392107, approval date: 21 September 2023). All procedures performed in studies involving human participants adhered to the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

If necessary, we can provide the raw data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Note

| 1 | The double leave-one-out (DLOO) method constructs Peer Ability measures using workers’ historical performance in other plots, ensuring these measures are predetermined and exogenous to current–period interactions. This approach is in the spirit of seminal work on peer effects, such as Mas and Moretti (2009), which uses exogenous variation in co-worker productivity to identify spillovers (Mas & Moretti, 2009). |

References

- Angrist, J. D., & Pischke, J.-S. (2009). Mostly harmless econometrics: An empiricist’s companion. Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Aoki, M. (2001). Toward a comparative institutional analysis. MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Arnott, R., & Stiglitz, J. E. (1991). Moral hazard and nonmarket institutions: Dysfunctional crowding out of peer monitoring? The American Economic Review, 81(1), 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandiera, O., Barankay, I., & Rasul, I. (2005). Social preferences and the response to incentives: Evidence from personnel data. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 120(3), 917–962. [Google Scholar]

- Belot, M., & Schröder, M. (2016). The spillover effects of monitoring: A field experiment. Management Science, 62(1), 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, E. S. (2012). The transparency paradox: A role for privacy in organizational learning and operational control. Administrative Science Quarterly, 57(2), 181–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, Y. (1997). Bringing strong ties back in: Indirect ties, network bridges, and job searches in China. American Sociological Review, 62(3), 366–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blader, S. L., & Tyler, T. R. (2009). Testing and extending the group engagement model: Linkages between social identity, procedural justice, economic outcomes, and extrarole behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(2), 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloom, N., Liang, J., Roberts, J., & Ying, Z. J. (2015). Does working from home work? Evidence from a Chinese experiment. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 130(1), 165–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, N., & Van Reenen, J. (2011). Human resource management and productivity. In Handbook of labor economics (Vol. 4, pp. 1697–1767). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Bowles, S. (2008). Policies designed for self-interested citizens may undermine “the moral sentiments”: Evidence from economic experiments. Science, 320(5883), 1605–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowles, S., & Polania-Reyes, S. (2012). Economic incentives and social preferences: Substitutes or complements? Journal of Economic Literature, 50(2), 368–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, J. S. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology, 94, S95–S120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropanzano, R., & Mitchell, M. S. (2005). Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. Journal of Management, 31(6), 874–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delery, J. E., & Doty, D. H. (1996). Modes of theorizing in strategic human resource management: Tests of universalistic, contingency, and configurational performance predictions. Academy of Management Journal, 39(4), 802–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, D., & Villeval, M.-C. (2008). Does monitoring decrease work effort?: The complementarity between agency and crowding-out theories. Games and Economic Behavior, 63(1), 56–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, L. (2001). The contingency theory of organizations. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Agency theory: An assessment and review. Academy of Management Review, 14(1), 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, A., & Kosfeld, M. (2006). The hidden costs of control. American Economic Review, 96(5), 1611–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, B. S., & Jegen, R. (2001). Motivation crowding theory. Journal of Economic Surveys, 15(5), 589–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagné, M., & Deci, E. L. (2005). Self-determination theory and work motivation. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26(4), 331–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosnell, G. K., List, J. A., & Metcalfe, R. D. (2020). The impact of management practices on employee productivity: A field experiment with airline captains. Journal of Political Economy, 128(4), 1195–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granovetter, M. (1985). Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. American Journal of Sociology, 91(3), 481–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, J. (1987). A taxonomy of organizational justice theories. Academy of Management Review, 12(1), 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollander, J. A., & Einwohner, R. L. (2004). Conceptualizing resistance. Sociological Forum, 19(4), 533–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmstrom, B., & Milgrom, P. (1991). Multitask principal–agent analyses: Incentive contracts, asset ownership, and job design. The Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, 7, 24–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House, R., Rousseau, D. M., & Thomashunt, M. (1995). The meso paradigm-a framework for the integration of micro and macro organizational-behavior. Research in Organizational Behavior: An Annual Series of Analytical Essays and Critical Reviews, 17, 71–114. [Google Scholar]

- Huselid, M. A. (1995). The impact of human resource management practices on turnover, productivity, and corporate financial performance. Academy of Management Journal, 38(3), 635–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (2019). Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. In Corporate governance (pp. 77–132). Gower. [Google Scholar]

- Jeworrek, S., & Mertins, V. (2022). Mission, motivation, and the active decision to work for a social cause. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 51(2), 260–278. [Google Scholar]

- Kandel, E., & Lazear, E. P. (1992). Peer pressure and partnerships. Journal of Political Economy, 100(4), 801–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolstad, J. T. (2013). Information and quality when motivation is intrinsic: Evidence from surgeon report cards. American Economic Review, 103(7), 2875–2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kung, J. K. (2002). Off-farm labor markets and the emergence of land rental markets in rural China. Journal of Comparative Economics, 30(2), 395–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, P. R., Lorsch, J. W., & Garrison, J. S. (1967). Organization and environment: Managing differentiation and integration. Division of Research, Graduate School of Business Administration, Harvard University. [Google Scholar]

- Lazear, E. P. (2000). Performance pay and productivity. American Economic Review, 90(5), 1346–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- List, J. A. (2007). Field experiments: A bridge between lab and naturally occurring data. The BE Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy, 6(2), 102202153806371747. [Google Scholar]

- Manski, C. F. (1993). Identification of endogenous social effects: The reflection problem. Review of Economic Studies, 60(3), 531–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mas, A., & Moretti, E. (2009). Peers at work. American Economic Review, 99(1), 112–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milgrom, P., & Roberts, J. (1990). The economics of modern manufacturing: Technology, strategy, and organization. American Economic Review, 80(3), 511–528. [Google Scholar]

- Milgrom, P., & Roberts, J. (1995). Complementarities and fit strategy, structure, and organizational change in manufacturing. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 19(2–3), 179–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagin, D. S., Rebitzer, J. B., Sanders, S., & Taylor, L. J. (2002). Monitoring, motivation, and management: The determinants of opportunistic behavior in a field experiment. American Economic Review, 92(4), 850–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nee, V. (1992). Organizational dynamics of market transition: Hybrid forms, property rights, and mixed economy in China. Administrative Science Quarterly, 37, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pache, A.-C., & Santos, F. (2013). Inside the hybrid organization: Selective coupling as a response to competing institutional logics. Academy of Management Journal, 56(4), 972–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y. (2004). Kinship networks and entrepreneurs in China’s transitional economy. American Journal of Sociology, 109(5), 1045–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pentland, B. T., & Feldman, M. S. (2005). Organizational routines as a unit of analysis. Industrial and Corporate Change, 14(5), 793–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, L., Snow, D. C., & McAfee, A. (2015). Cleaning house: The impact of information technology monitoring on employee theft and productivity. Management Science, 61(10), 2299–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. Simon & Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau, D. (1995). Psychological contracts in organizations: Understanding written and unwritten agreements. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, H. A. (2013). Administrative behavior. Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Staats, B. R., Dai, H., Hofmann, D., & Milkman, K. L. (2017). Motivating process compliance through individual electronic monitoring: An empirical examination of hand hygiene in healthcare. Management Science, 63(5), 1563–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, F. W. (1911). The principles of scientific management. NuVision Publications, LLC. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton, P. H., Ocasio, W., & Lounsbury, M. (2012). The institutional logics perspective: A new approach to culture, structure, and process. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tyler, T. R., & Blader, S. L. (2003). The group engagement model: Procedural justice, social identity, and cooperative behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 7(4), 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walder, A. G. (1995). Local governments as industrial firms: An organizational analysis of China’s transitional economy. American Journal of Sociology, 101(2), 263–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, O. E. (1975). Markets and hierarchies. Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, O. E. (1991). Comparative economic organization: The analysis of discrete structural alternatives. Administrative Science Quarterly, 36(2), 269–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K. Z., Gao, G. Y., & Zhao, H. (2017). State ownership and firm innovation in China: An integrated view of institutional and efficiency logics. Administrative Science Quarterly, 62(2), 375–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).