1. Introduction

In the context of a dynamically changing organizational environment, leaders and teams are increasingly required to operate under conditions of ambiguity, complexity, and multilayered social interdependencies. In such situations, effective leadership demands not only strategic competencies but also a developed capacity for self-reflection, encompassing both an evaluation of one’s actions and attentiveness to their relational consequences. The concept of relational reflexivity represents a theoretical attempt to capture this capacity as a multidimensional cognitive, emotional, and communicative process that integrates personal insight with social responsibility (

Barge, 2004). Relational reflexivity differs from traditional introspective approaches in that it is not confined to an internal monologue. Rather, it is grounded in the co-construction of meaning through interaction, mutual influence, and the leader’s ethical responsibility for the quality of relationships with team members.

A. L. Cunliffe and Eriksen (

2011) emphasized that relational leadership is fundamentally dialogic, centering on meaning-making and accountability emerging within relationships rather than within the individual leader. As

Knight (

2016) notes, it is a process rooted in inclusive communication, metacognitive analysis of context, and active regulation of one’s influence on group dynamics.

Empirical studies on team reflexivity suggest that teams engaging in reflective practices tend to achieve higher levels of decision-making quality, innovation, and job satisfaction.

Liu et al. (

2025) demonstrated that managerial teams characterized by strong task-related and emotional reflexivity made better decisions and reported greater satisfaction with their performance. In the study by

Hammedi et al. (

2011), team reflexivity mediated the relationship between leadership style and decision quality under conditions requiring creativity. Similarly,

Lee et al. (

2014) found that high-performing teams owed part of their success to systematic reflective practices. Collectively, these studies indicate that reflexivity supports leadership effectiveness through multiple pathways.

West (

2000) likewise conceptualized reflexivity as a core process through which teams critically examine objectives, strategies, and methods, thereby enabling innovation and adaptive performance. Reflexive practices enhance decision quality by facilitating a critical assessment of assumptions, supporting innovation through the integration of diverse viewpoints and a balance between exploration and implementation, as well as promoting psychological safety by fostering open communication and feedback. These mechanisms converge on a core proposition: reflexivity enables leaders and teams to navigate complexity not through control but through structured reflection and collective meaning-making.

The link between reflexivity and leadership effectiveness has also been confirmed in research that considers contextual organizational factors.

Lyubovnikova et al. (

2015) showed that team reflexivity mediated the relationship between authentic leadership and team performance. In another study,

van Neerijnen et al. (

2016) demonstrated that reflexivity enabled teams to cope with cognitive paradoxes and enhanced their ambidexterity. However, the effectiveness of team reflexivity may be weakened by structural factors such as decision centralization or supervisory control, as indicated by

de Waal et al. (

2018).

Despite the increasing relevance of relational reflexivity in leadership theory, it remains insufficiently operationalized as an independent empirical construct. Existing measurement tools tend to focus on isolated aspects such as leader self-awareness (

Showry & Manasa, 2014), communication competencies (

Hedman, 2015), or feedback-giving style (

Harvey & Green, 2022), but they fail to capture reflexivity as a complex, relationally embedded process. Moreover, most existing studies rely on qualitative data, which limits the possibility of quantitative comparison and the testing of complex mediational models. Despite the increasing relevance of relational reflexivity in leadership theory, it remains insufficiently operationalized as an independent empirical construct. As

Raes et al. (

2011) note, advancing theory on team and leadership processes requires instruments that capture interactions across multiple levels rather than focusing only on single traits or outcomes. The Relational Reflexivity in Management Questionnaire (RRMQ) addresses this gap by offering the first multidimensional and psychometrically validated measure that integrates interpersonal competencies with ethical–metacognitive reflection, enabling both robust quantitative assessment and theory-driven model testing.

The present study aims to develop and validate the (RRMQ) as a multidimensional measure of reflexive leadership competencies. Building on existing theories of dialogic leadership and relational reflexivity, this research addresses a central guiding question: Can relational reflexivity be operationalized as a five-dimensional, psychometrically valid construct in management contexts? Sport management was chosen as the first-validation context because it embodies key conditions where relational reflexivity is most salient. Students in this field are trained for environments that require teamwork, rapid communication under pressure, and constructive handling of conflicts or mediation processes. These features make sport management a suitable and rigorous domain for the initial validation of the RRMQ, with insights transferable to broader organizational contexts.

2. Literature Overview

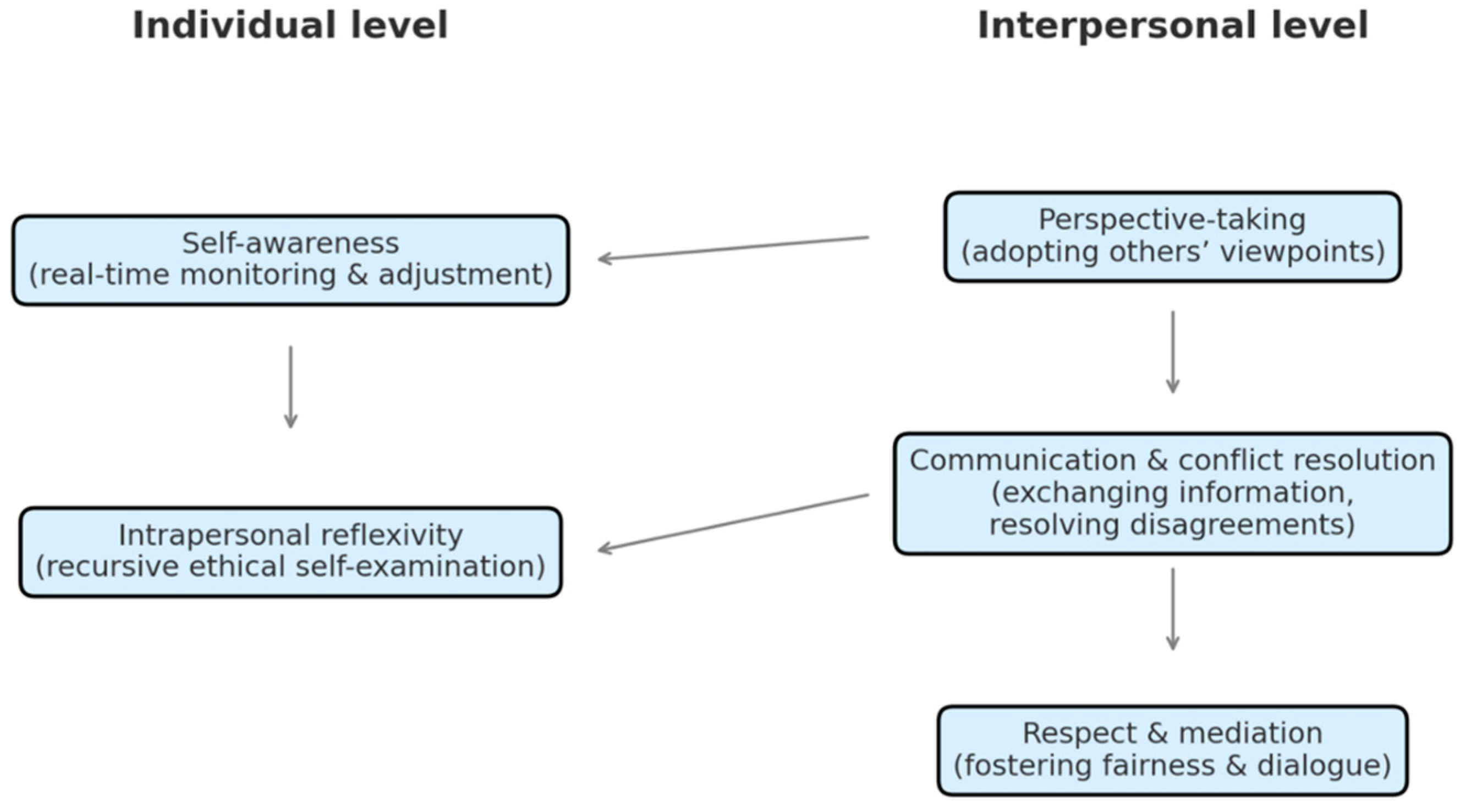

The present study is grounded in five theoretically derived dimensions of relational reflexivity: self-awareness, perspective-taking, communication and conflict resolution, respect and mediation, and intrapersonal reflexivity. Each of these elements is based on a distinct line of research and has been empirically identified in the literature as relevant to practical and ethical team leadership. Conceptually, the five dimensions reflect distinct yet interdependent mechanisms within the broader framework of relational reflexivity. Self-awareness and intrapersonal reflexivity operate at the individual level; the former focuses on real-time regulation of behavior, while the latter involves recursive self-examination and ethical alignment. Perspective-taking serves as a cognitive-empathetic bridge to others, enabling leaders to anticipate the needs and reactions of those around them. Communication and conflict resolution represent behavioral enactments of reflexivity in group settings, while respect and mediation ground these actions in normative commitments to dignity, fairness, and repair. Together, these domains constitute a comprehensive architecture of reflexive leadership.

Taken together, the five dimensions—self-awareness, perspective-taking, communication and conflict resolution, respect and mediation, and intrapersonal reflexivity—constitute the cognitive, emotional, and ethical infrastructure of relational reflexivity. Self-related capacities foster introspective clarity and ethical intention; interpersonal capacities ensure dialogic engagement and trust-building. This multidimensional structure aligns with dialogic leadership theory (

Barge, 2004) and relational reflexivity frameworks (

Knight, 2016), where leadership is understood not as position or personality, but as an evolving co-construction of meaning, accountability, and ethical presence within complex social systems. This conceptualization is visually summarized in

Figure 1, which organizes the five dimensions into two interrelated levels: individual (self-awareness, intrapersonal reflexivity) and interpersonal (perspective-taking, communication and conflict resolution, respect and mediation). The schematic highlights their functional distinctions while illustrating expected conceptual interrelations, thereby providing a clear operational map for the subsequent empirical validation of the RRMQ.

2.1. Self-Awareness

Self-awareness constitutes a foundational dimension of reflexive leadership and a prerequisite for making ethical decisions and fostering adaptive team functioning. Conceptually, self-awareness refers to an individual’s capacity to monitor and regulate internal cognitive, affective, and motivational states, and to recognize how this influences one’s actions and relationships (

Hoyle & Duvall, 2012). Within leadership research, it is considered a critical antecedent to emotional intelligence and authentic behavior. While often conflated with reflexivity more broadly, in this framework, self-awareness refers specifically to the real-time monitoring and adjustment of behavior in situational contexts. For example, a leader may notice rising defensiveness in a conversation and deliberately adjust tone or phrasing to maintain clarity and rapport.

Ye et al. (

2020) conducted a large-scale empirical study involving 79 teams, demonstrating that leaders with high self-awareness were more capable of interpreting feedback and adapting their behavior to enhance group alignment and task engagement. Similarly,

Tenenbaum and Filho (

2016), using a multidimensional assessment model, found that athletes with higher self-awareness were more likely to interpret pressure situations as facilitative, leading to improved real-time decision-making. These findings are echoed by

Hepler and Feltz (

2012), who showed that self-aware athletes more effectively used intuitive decision-making heuristics, such as the “Take the First” rule, under dynamic sport conditions. Self-awareness in this framework refers to real-time monitoring and adjustment of one’s own behaviors, with an emphasis on immediate regulation of actions in social and organizational

contexts.

2.2. Perspective-Taking

Perspective-taking, as a core element of reflexive leadership, denotes the deliberate cognitive act of considering the viewpoints, mental models, and emotional experiences of others within a team or organizational context. Unlike empathy, which is primarily affective, perspective-taking is conceptualized as a metacognitive process that facilitates inclusive dialogue, anticipatory reasoning, and contextual decision-making (

Davis, 1983). In the leadership literature, this capacity is associated with improved team dynamics, reduced conflict, and enhanced collaboration.

Calvard (

2010) conceptualizes perspective-taking as a deliberative, cognitively oriented skill that facilitates leaders in managing uncertainty, absorbing diverse feedback, and balancing competing stakeholder needs.

Meanwhile,

Gustavson and Liff (

2014) emphasize that leaders who understand how others perceive their values are better positioned to build shared meaning, which in turn fosters deeper alignment and trust within teams. However, the literature also offers essential caveats.

Vorauer (

2013), drawing from experimental psychology, cautions that under evaluative threat, perspective-taking may paradoxically increase anxiety and self-monitoring, potentially impairing authentic engagement. These findings underscore that while perspective-taking is a critical component of reflexive leadership, its effectiveness is contingent on psychological safety and context-sensitive application.

2.3. Communication and Conflict Resolution

Effective leadership in team settings is inseparable from the dual capacity to communicate reflexively and to resolve conflict constructively. As

Pearce and Cronen (

1980) illustrate through their Coordinated Management of Meaning framework, communication is a reflexive process of coordinating lived and told stories.

Bushe and Marshak (

2009) extend this within dialogic organizational development, arguing that organizational change is generated through repeated, reflexive dialogues that co-create shared realities. Leaders who adopt a reflexive stance facilitate conversations that surface assumptions, enable feedback, and invite collective interpretation.

Hedman (

2015) emphasizes that effective communication in reflexive leadership teams is a continuously reflective practice—where team members monitor interaction patterns and adjust relational dynamics to support more effective collaboration.

Complementary to communication is the domain of conflict resolution, which reflexive leaders do not treat as a disruption but as an entry point for growth.

Vealey (

2017), in her case analysis of a collegiate basketball team, demonstrated how structured reflexive interventions—termed “consulting below zero”—allowed athletes to articulate grievances, rebuild interpersonal trust, and reestablish performance alignment. Similarly,

Godin (

2017), in an empirical study of mediation in elite sport, argues that reflexive mediation in elite sport goes beyond procedural resolution—it involves confronting moral discomfort and emotional rupture, thereby enabling not only resolution but relational repair. Yet not all feedback styles support reflexivity.

Harvey and Green (

2022) found that leaders with excessively agreeable communication habits may inadvertently suppress reflective growth by prioritizing emotional comfort over behavioral challenges.

2.4. Respect and Mediation

Respect and mediation, while often treated as discrete ethical or procedural concerns, are increasingly recognized as interdependent mechanisms within reflexive leadership. Respect, in this context, is not reducible to politeness or social decorum but is instead understood as a relational commitment to acknowledging the dignity, agency, and experiential validity of others (

Noddings, 2012). When integrated into mediation practices, respect forms the ethical foundation of conflict resolution processes that aim not only to manage disagreement but also to restore and deepen social bonds. In high-performance settings, such as sports,

Godin (

2017) emphasizes that effective mediation in elite sport cannot occur without respect, as it undermines legitimacy, trust, and sustained behavioral change.

The importance of respect is also reflected in culturally embedded conflict rituals.

Rees and Miracle (

1984), in a cross-cultural study of traditional games, observed that many non-Western sport contexts incorporate ritualized mechanisms of de-escalation and reconciliation. These mechanisms, such as honor gestures or symbolic reparations, institutionalize respect as a condition for re-entry into the group. Such practices parallel contemporary relational models of conflict mediation, which prioritize dialogue over punishment and mutual understanding over adjudication.

In applied leadership practice,

Vealey (

2017) demonstrated that respect was both a precondition and an outcome of her “below-zero” consulting intervention with a college basketball team. By facilitating story-sharing and reflective listening, leaders and athletes reestablished a culture of mutual regard that had eroded under the pressure of competition and internal mistrust. These findings align with those of

Sherry et al. (

2007), who argue that ethical leadership in sport necessitates reflexive engagement with systemic conflicts of interest.

2.5. Intrapersonal Reflexivity

Intrapersonal reflexivity refers to the internal process by which individuals examine their assumptions, values, emotional responses, and identity constructions concerning their role as leaders. It differs from general self-awareness by emphasizing the dynamic and dialogical character of internal reflection—a recursive interplay between belief systems, ethical orientations, and lived experiences (

Archer, 2003). Distinct from self-awareness, intrapersonal reflexivity denotes a temporally extended process of recursive ethical self-examination. It involves revisiting past decisions and projecting future commitments to achieve coherence between values, identity, and professional practice. As

Brown (

2015) argues, such definitional clarity is crucial when constructs are conceptually close yet empirically separable.

Within leadership development, intrapersonal reflexivity is seen as a prerequisite for adaptive learning, particularly in complex moral or relational contexts.

A. Cunliffe and Coupland (

2012) describe narrative reflexivity as an embodied, dialogic process through which leaders construct, deconstruct, and reconstruct their identities in response to lived experience. These narratives are not static but evolve through ongoing sense-making, allowing leaders to align their actions with their personal values and the social context. This concept is further elaborated through “place-based reflection,” in which leaders reflect not only on abstract values but on how their upbringing, social context, and physical environments shape their decision-making. Reflective leadership development increasingly considers how leaders’ identities are shaped by the spatial, historical, and emotional dimensions of their context. Such “place-based reflection” fosters humility and contextual sensitivity—qualities essential to ethical leadership in complex environments (

Raelin, 2014). By contrast, intrapersonal reflexivity denotes recursive ethical self-examination over time, focusing on the evaluation of values, motives, and principles beyond immediate behaviors. This distinction clarifies that self-awareness captures situational regulation, whereas intrapersonal reflexivity captures ongoing metacognitive and ethical reflection.

Existing frameworks tend to isolate components such as self-awareness or empathy, but rarely address their integration within the broader interpersonal and ethical dynamics of leadership. This fragmentation has hindered efforts to assess relational reflexivity as a coherent, multidimensional construct. To advance both theory and practice, there is a need for a validated instrument that captures the complexity of relational reflexivity in organizational contexts and enables its systematic study across populations and settings. Unlike existing tools that isolate single facets (e.g., empathy, communication style, self-awareness), the RRMQ integrates five dimensions into one multidimensional measure. This provides a unique combination of intrapersonal, interpersonal, and ethical elements not covered jointly by previous scales. Previous attempts to operationalize reflexivity have tended to focus on single aspects, such as self-awareness or communication style, which limited their usefulness in multidimensional research.

Table 1 provides a synthetic comparison of these instruments, illustrating how the RRMQ addresses the gap in the literature (see

Table 1).

The authors aimed to operationalize a construct that has thus far primarily functioned within qualitative and theoretical frameworks, and to empirically assess its factor structure and conceptual validity using quantitative methods. To achieve this aim, the study involved identifying the dimensional structure of relational reflexivity through exploratory factor analysis (EFA), followed by confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) conducted on an independent subsample. The process also involved verifying the theoretical coherence, item specificity, and empirical consistency of the proposed model in relation to its conceptual foundations.

Building on these conceptual foundations, the following section formulates three hypotheses that guided the empirical validation of the RRMQ. First, it was hypothesized that relational reflexivity could be accurately modeled as five interrelated yet psychologically distinct latent factors: self-awareness, perspective-taking, communication and conflict resolution, respect and mediation, and intrapersonal reflexivity (H1). Second, it was expected that exploratory factor analysis would yield components corresponding to these theoretical dimensions, with each item loading on a single factor (H2). Third, it was anticipated that the five-factor model would achieve acceptable fit indices in confirmatory factor analysis conducted on an independent subsample, thus confirming its structural validity (H3).

3. Methods

3.1. Participants

The sample used for the exploratory factor analysis (EFA) consisted of 524 undergraduate students enrolled in the Sport Management program at the Jerzy Kukuczka University of Physical Education in Katowice, aged between 20 and 25 years. The final sample (N = 524) represented about 65% of the total population of sport management students enrolled at the institution. In the full dataset (N = 524), gender was reported by 519 participants (55.6% female, 44.4% male), with five missing responses (1.0%). The EFA was conducted on this full sample. For the CFA subsample (n = 400), gender proportions were preserved (55.0% female, 44.0% male, 1.0% missing). A chi-square test indicated no significant difference between the subsample and the full dataset (χ

2(1) = 0.12,

p = 0.73). The CFA sample (n = 400) was generated by drawing a simple random subsample from the full pool of 524 participants using IBM SPSS Statistics v.29 (random seed set to 2024 to ensure reproducibility). To confirm comparability, independent-samples

t-tests and chi-square tests were conducted on age and gender distributions, as well as mean reflexivity scale scores. No significant differences were found between the subsamples (all

p > 0.40). Thus, the EFA and CFA groups can be considered equivalent in sociodemographic and baseline reflexivity characteristics. Participants were recruited via university mailing lists and classroom announcements. All respondents were full-time graduate or final-year undergraduate students enrolled in sport management. This ensured a relatively homogeneous level of academic experience relevant to the construct of relational reflexivity. Inclusion criteria required current enrollment in these programs and informed consent to participate. The only exclusion criterion applied was incomplete survey data. The exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted on the full dataset (N = 524), yielding >20 participants per item (25 items), which exceeds recommended thresholds (

Costello & Osborne, 2005;

Fabrigar et al., 1999). To corroborate the structure, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted on a randomly drawn subsample from the same sampling frame (n = 400), which also meets commonly accepted recommendations for factor analysis (

Hair et al., 2010). Although the preferred methodological practice involves conducting CFA on an entirely independent sample, the approach of selecting a random subsample from the same respondent pool is considered acceptable during the initial stages of psychometric instrument validation, provided that the CFA is not used for iterative model fitting or structural modifications (

Fabrigar et al., 1999;

Worthington & Whittaker, 2006).

As emphasized by

Kline (

2016), in cases where access to large, independent replication samples is limited, conducting CFA on a statistically independent subsample drawn from the same dataset is methodologically justified, particularly when the aim is to verify rather than optimize a previously identified factor structure.

Harrington (

2008) and

Costello and Osborne (

2005) likewise confirm that such an approach is acceptable during the early stages of construct validation, especially under constraints related to population accessibility.

The random selection of 400 observations for CFA from the larger EFA sample ensured statistical independence between the two analytical phases, while also providing an adequate sample size for estimating the parameters of a multidimensional model (

Hair et al., 2010). Since the CFA model was tested without any post hoc modifications to the structure established through EFA, the resulting fit indices can be considered a valid assessment of structural validity, despite both analyses being based on the same source population.

3.2. Research Instrument

The (RRMQ) was developed based on a review of empirical and conceptual literature on team and relational reflexivity. The initial version of the instrument included 25 items corresponding to five theoretical components:

The full wording of the initial 25 items and the final 15 retained items is presented in

Table 2 and

Table 3.

3.3. Item Generation and Content Validity

An initial pool of 30 items was generated based on a targeted review of conceptual and empirical literature on reflexivity and related constructs (

Barge, 2004;

Knight, 2016), together with best-practice guidelines for scale development (

Boateng et al., 2018;

DeVellis, 2017). Items were written to reflect one of five theoretically specified dimensions (self-awareness, perspective-taking, communication & conflict resolution, respect & mediation, intrapersonal reflexivity). Each item was linked to an a priori item blueprint specifying its dimension and intended behavioral referent. Three doctoral-level experts in organizational psychology evaluated all items for relevance and clarity using a 4-point scale (1 = not relevant/unclear; 4 = highly relevant/very clear), following established content-validity procedures (

Lynn, 1986;

Polit et al., 2007). Item-level content validity indices (I-CVI) and the scale-level average CVI (S-CVI/Ave) were computed. Items with I-CVI = 1.00 were retained, those with I-CVI = 0.67 were revised, and those with I-CVI < 0.67 were removed (

Lawshe, 1975). Five items were removed as a result of this process, leaving 25 items that proceeded to pilot testing. Numeric CVI tables are provided in

Appendix A.

Respondents were asked to rate their agreement with each statement on a seven-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). The items were constructed to reflect both cognitive and affective-communicative aspects of reflexivity.

Psychometric criteria did not merely drive the reduction from 25 to 15 items but also reflected practical considerations of scale efficiency and conceptual clarity. In organizational settings, shorter instruments are more likely to be completed thoroughly and without fatigue, particularly in time-constrained environments such as managerial assessments or team workshops. Methodologically, three-item subscales are commonly used when item specificity is high and dimensional distinctiveness is preserved (

Little, 2013;

Worthington & Whittaker, 2006). The selection procedure balanced statistical indicators—such as factor loadings and low uniqueness—with theoretical alignment to ensure that each retained item captured core aspects of its respective construct.

3.4. Research Procedure

The primary aim of the statistical analysis was to empirically validate the factor structure of the newly developed instrument designed to measure relational reflexivity in management. The validation process followed a two-stage procedure involving exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) conducted on two statistically independent subsamples. Additionally, item selection was performed using both psychometric and theoretical criteria. Before conducting factor analyses, the dataset was screened for missing values and outliers. No missing responses were detected across the 524 cases and 25 initial items, eliminating the need for imputation or listwise deletion. Outlier diagnostics based on standardized z-scores (±3.0 as threshold) indicated no univariate outliers, and visual inspection of distributions confirmed normal range variability. Thus, the dataset could be analyzed in its entirety without case removal or data adjustment. All analyses were carried out in Jamovi (version 2.4.8). This ensured that the reported EFA and CFA results are not affected by missingness or data irregularities, thereby strengthening the robustness of the findings.

3.4.1. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

Exploratory factor analysis was conducted to identify the latent structure of the variables and assess the extent to which the item configuration reflected the theoretically assumed dimensions of the construct. The analysis employed the Unweighted Least Squares (ULS) method, which is recommended in cases where multivariate normality cannot be considered (

Fabrigar et al., 1999). This method enables the estimation of factor structure without maximizing the likelihood function, making it more robust to deviations from normality in response distributions (

Osborne, 2014). An oblique rotation (oblimin) was employed to facilitate correlations between factors, which is consistent with recommendations for theoretically interrelated psychological constructs (

Brown, 2015;

Costello & Osborne, 2005). The number of factors was determined based on a scree plot, eigenvalues greater than 1.00, theoretical interpretability, and alignment with the conceptual model of relational reflexivity. Data suitability for factor analysis was assessed using Bartlett’s test of sphericity and the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy. Both are standard tests for evaluating the appropriateness of a dataset for factor analysis (

Field, 2013). KMO was assessed both at the overall level and for individual items (MSA—Measure of Sampling Adequacy). Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted using unweighted least squares (ULS) with oblimin rotation. Given the ordinal nature of Likert-scale items, analyses were based on a polychoric correlation matrix. Factor retention was guided by both eigenvalues >1.0 and parallel analysis, which converged on a five-factor solution. Items with primary loadings ≥0.40 and cross-loadings exceeding 0.30 were flagged, and items were retained only if the difference between the primary and secondary loadings exceeded 0.20. These criteria ensured that the retained items were both statistically robust and theoretically aligned.

3.4.2. Item Selection for the Final Model

Based on the EFA results, items were selected using a combination of psychometric and content-related criteria. The selection included:

Factor loading ≥ 0.60 (preferred)

Uniqueness ≤ 0.50 (preferred)

Unambiguous association with a single factor (no substantial cross-loadings)

Semantic and theoretical alignment with the intended construct dimension

The final item pool ensured balanced representation of the five dimensions: self-awareness, perspective-taking, communication and conflict resolution, respect and mediation, and intrapersonal reflexivity.

3.4.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

Confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to validate the five-factor structure identified through EFA empirically. The model included five latent variables, each with three observable indicators. The study employed structural equation modeling (SEM) and robust maximum likelihood estimation (MLR), which are recommended for analyzing Likert-scale data and large samples (

Kline, 2016).

Model fit was evaluated using standard indices:

RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation)

CFI (Comparative Fit Index)

TLI (Tucker–Lewis Index)

Chi-square test with degrees of freedom

Additionally, the statistical significance and magnitude of factor loadings, as well as the covariances between latent factors, were examined. All analyses were conducted using the Jamovi software environment (

The jamovi project. Jamovi (Version 2.6) [Computer Software], 2024). The present validation stage focused on structural validity through exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses. Convergent and discriminant validity, as well as potential common method variance, were beyond the scope of this stage and are addressed in the Limitations as areas for future research.

3.5. Ethical Approval and Data Protection

Participation in the study was entirely voluntary, and each participant could withdraw at any time by closing the survey without any consequences. Completing the questionnaire took approximately 15 min. The survey was fully anonymous—no personally identifiable data, such as name, email address, or IP address, was collected. Responses were analyzed exclusively in aggregated form, ensuring that individual participants could not be identified. The data were stored in encrypted form and were accessible only to the principal investigator. The study was conducted in accordance with Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and the Council (GDPR), adhering to the principles of data minimization, transparency, and purpose limitation.

All responses will be permanently deleted no later than 31 December 2026, following the completion of statistical analysis. The results will be reported exclusively in aggregated form in scientific publications, research reports, or conference presentations. Proceeding with the survey was considered equivalent to informed consent to participate under the conditions outlined above.

The study protocol received approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee for Scientific Research at the Jerzy Kukuczka University of Physical Education in Katowice (Resolution No. 7-XII/2024). All research procedures were designed and conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (

World Medical Association, 2013), with full respect for participant dignity, the proportionality of research methods, and the accountability of the researcher. The committee raised no objections to the survey instrument or research design.

4. Results

4.1. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

The first stage of analysis was exploratory, aiming to identify the factor structure of relational reflexivity within the management context. The study, conducted on the complete set of 25 items (N = 524), revealed a five-factor structure fully aligned with the theoretical assumptions of the construct. The identified components reflected the following dimensions: (1) self-awareness, (2) perspective-taking, (3) communication and conflict resolution, (4) respect and mediation, and (5) intrapersonal reflexivity. Strong quality indicators confirmed data adequacy. The KMO value was 0.955, indicating excellent sampling adequacy, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was statistically significant (χ2 = 6315, df = 300, p < 0.001). The eigenvalues for the five extracted factors exceeded the threshold of 1.00 and were as follows: 6.5, 4.5, 3.6, 2.5, and 1.3, respectively. The total variance explained was 53.5%. Following the identification of the five-factor solution and the overall adequacy of the data, the next step involved refining the instrument by selecting the most representative items. Based on the results of the EFA, 15 items were selected to represent the five factors—three per dimension—using the following criteria: factor loading magnitude, low uniqueness, and apparent association with a single factor. This refined version of the questionnaire was subsequently used in the CFA.

Each factor grouped items that were thematically cohesive and conceptually distinct. For example, items addressing active listening, resolving misunderstandings, and maintaining clear communication clustered into a strong, coherent communication and conflict resolution factor, with loadings up to 0.800 (“I resolve misunderstandings…”) and 0.751 (“I quickly address conflicts…”). The perspective-taking factor captured cognitive and affective behaviors related to considering others’ viewpoints, with loadings up to 0.716. The intrapersonal reflexivity factor is related to one’s willingness to reassess beliefs and engage in critical self-reflection (with loadings up to 0.736). Self-awareness encompassed the awareness of how one’s decisions and behaviors affect team dynamics (primary loading = 0.869). Lastly, respect and mediation included items related to cultivating trust and managing interpersonal tensions (with loadings ranging from 0.303 to 0.393).

The factor structure was clear, with most items demonstrating strong and unambiguous loadings onto their respective components, confirming both diagnostic value and conceptual alignment (see

Table 2). No substantial cross-loadings were observed, and item uniqueness remained within acceptable limits (average below 0.50), indicating good fit between items and their assigned latent components. Although some standardized loadings slightly exceeded 1.0, no estimation problems (e.g., negative error variances) occurred. The high correlations observed among certain factors reflect their theoretical relatedness rather than the instability of the model.

In terms of instrument construction, the results of the EFA served as the basis for further optimization, reducing the number of items without sacrificing conceptual completeness. Three of the best-performing items were selected from each of the five dimensions, based on three concurrent criteria: high factor loadings, low uniqueness, and semantic congruence with the theoretical definition of the component. The final 15 items were retained through a combination of empirical and theoretical criteria. Items were selected if they demonstrated strong primary loadings (≥0.50) without cross-loadings above 0.30, low uniqueness (<0.50), and meaningful contributions to internal consistency within their respective dimensions. Beyond these statistical thresholds, theoretical alignment was applied to ensure that each of the five proposed dimensions—self-awareness, perspective-taking, communication & conflict resolution, respect and mediation, and intrapersonal reflexivity—remained conceptually represented. This dual approach ensured that the final 15-item solution struck a balance between psychometric rigor and theoretical integrity.

The final 15 items represent those with the strongest loadings and theoretical alignment, leaving three items per dimension. This selection ensured both conceptual coverage and a parsimonious, user-friendly instrument. The resulting 15-item version was subjected to a second round of EFA, which confirmed the stability of the five-factor structure and showed no negative consequences of scale reduction. The total explained variance in this version increased to 56.1% (see

Table 3). The observed improvement in RMSEA from 0.0498 to 0.0338 reflects not only statistical refinement but also meaningful gains in model parsimony and interpretability. In practical terms, a better-fitting model facilitates more accurate assessment of latent traits, enhances the reliability of comparative studies, and increases the utility of the instrument in real-world leadership diagnostics. These improvements suggest that the reduced item set can deliver precise measurements with less redundancy, which is critical in applied organizational contexts where brevity and clarity are essential.

Table 4 presents the factor correlation matrix obtained from the oblique (oblimin) EFA solution. Moderate associations were observed between some dimensions (e.g., F1 with F2, F1 with F5), whereas others remained largely independent. This pattern supports the conceptualization of relational reflexivity as multidimensional yet integrated.

Notably, the factor structure of the instrument proved not only to be psychometrically robust but also theoretically coherent, consistent with the assumption that relational reflexivity integrates cognitive, emotional, and communicative dimensions (

Barge, 2004;

Knight, 2016). Thus, the EFA provided not only preliminary support but also operational validation for conceptualizing relational reflexivity as a measurable construct within organizational contexts.

4.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

In the second stage, confirmatory factor analysis was conducted on an independent subsample of 400 participants to verify the structure identified in the EFA. The five-factor model, composed of fifteen items, was designed as a latent structure with three observed indicators per component.

The CFA results confirmed that all items loaded significantly and unambiguously onto their designated factors, with no evidence of cross-loadings or redundancy. Factor loadings ranged from 0.89 to 1.13, and all path coefficients were statistically significant (

p < 0.001). The structure retained conceptual clarity and psychometric coherence, confirming its structural validity. Particularly well-performing components included

communication and conflict resolution, as well as

intrapersonal reflexivity, which demonstrated high internal consistency and strong alignment with their theoretical definitions. The dimensions

perspective-taking,

respect,

and mediation were more thematically diverse, possibly due to their broader relational and socio-emotional content (

Table 5).

Model fit indices were within ranges considered excellent in the methodological literature: RMSEA = 0.0605 (90% CI: 0.0497–0.0714), CFI = 0.955, and TLI = 0.941. The chi-square test was significant (χ2 = 194, df = 80, p < 0.001), a common finding in large samples, and does not inherently indicate a poor model fit. Correlations between latent variables indicated moderate to strong interdependence among interpersonal components, especially between communication and conflict resolution and respect and mediation, consistent with theoretical claims of a shared foundation in relational competencies. Correlation coefficients among factors ranged from r = 0.59 to 0.92.

The final model was evaluated as both statistically and theoretically sound. Each subscale score is computed as the mean of its three items. A total RRMQ index can be calculated as the mean of all 15. Confirmation of the five-factor structure through CFA suggests that relational reflexivity can be validly conceptualized as a multifaceted construct composed of interrelated yet distinct dimensions. This implies that the developed questionnaire can be reliably used in empirical research on management processes as well as in practical organizational contexts, such as leadership diagnostics, coaching interventions, and executive development programs. A significant contribution of this study lies in the development of the Relational Reflexivity Measurement Questionnaire (RRMQ). Despite the theoretical richness of the construct, relational reflexivity has remained underexplored in quantitative research. Unlike existing tools that isolate single facets (e.g., empathy, communication style, self-awareness), the RRMQ integrates five dimensions into one multidimensional measure. This integrative approach offers a unique combination of intrapersonal, interpersonal, and ethical elements that have not been previously covered jointly by earlier scales.

5. Discussion

The results of this study confirmed the five-factor structure of relational reflexivity, aligning with the theoretical model that encompasses self-awareness, perspective-taking, communication and conflict resolution, respect and mediation, and intrapersonal reflexivity. This structure demonstrated consistency across both exploratory and confirmatory analyses, and all items loaded distinctly onto their respective latent factors. The findings represent not only empirical confirmation of theoretical assumptions but also a significant step toward the development of a reliable and valid instrument for quantitatively measuring relational reflexivity. This finding is consistent with recent meta-analytic research, which suggests that team reflexivity reliably predicts team effectiveness under varying contingencies (

Leblanc et al., 2024).

A significant contribution of this study is the design and empirical validation of a novel questionnaire that enables the operational assessment of relational reflexivity as a measurable construct. To date, research in this area has primarily relied on qualitative methods (

Barge, 2004;

Knight, 2016) or focused on adjacent concepts such as team reflexivity, without isolating the relational component. There has been a lack of instruments capable of assessing this competency at both the individual and team levels while meeting psychometric standards. Recent intervention studies also suggest that guided reflexivity processes can be deliberately fostered to improve team functioning (

Santos et al., 2025), and systematic reviews emphasize their close interplay with emotional regulation at work (

Cova & Farnese, 2025). The instrument developed here fills that gap by offering a structurally stable and theoretically grounded operationalization of relational reflexivity.

The findings are consistent with previous studies.

Liu et al. (

2025) demonstrated that both cognitive and emotional reflexivity improved decision quality and satisfaction in management teams.

Hammedi et al. (

2011) found that reflexivity mediated the relationship between leadership style and decision effectiveness in innovation contexts. Similarly,

Lee et al. (

2014) showed that high-performing teams benefited from systematic reflective practices. The current findings support these conclusions, with the communication, conflict resolution, and intrapersonal reflexivity dimensions exhibiting both conceptual coherence and empirical stability.

The respect and mediation component, although statistically the weakest, aligns with existing evidence on the importance of respectful culture and conflict mediation in leadership. Although specific items of the Respect & Mediation factor exhibited moderate loadings in EFA, their retention was justified by both theoretical and empirical grounds. Removing these items would have risked underrepresenting key aspects of respect and mediation behaviors that are central to relational reflexivity. Moreover, subsequent CFA confirmed their adequacy, as standardized loadings fell within acceptable ranges and overall model fit remained satisfactory. This approach is consistent with recommendations to balance statistical indicators with conceptual importance in scale development (

Hair et al., 2010), ensuring that all five dimensions of the construct retained both psychometric and theoretical integrity. Therefore, the Respect & Mediation factor was retained in its entirety, as its theoretical indispensability and CFA confirmation outweighed the moderate EFA loadings observed for some of its items.

de Waal et al. (

2018) demonstrated that the quality of interactions between management boards and supervisory bodies depends on the level of reflexivity and constructive handling of tensions. In the current study, this component was strongly correlated with communication and conflict resolution, indicating a solid foundation in everyday interpersonal skills. Given the high intercorrelation between Communication and Conflict Resolution, Respect, and Mediation (r = 0.92), future research should consider testing a second-order model to determine whether these two factors are subdimensions of a broader latent construct. Such hierarchical modeling could clarify whether the conceptual overlap reflects true construct fusion or merely shared variance due to measurement proximity. While current item content supports distinct labeling, it is essential to examine whether this distinction holds across different populations and organizational cultures. This finding aligns with recent evidence suggesting that transformational leadership enhances both reflexivity and resilience in project teams (

Han et al., 2025). Equally significant was the confirmation of structural validity in the CFA. Fit indices (RMSEA, CFI, TLI) fell within the recommended thresholds (

Brown, 2015;

Kline, 2016), and factor intercorrelations showed moderate covariation without collinearity, indicating that relational reflexivity can be conceptualized as a multidimensional yet coherent construct measurable via a compact, psychometrically sound tool. Moreover,

Liu et al. (

2025) demonstrated that team reflexivity also predicts feedback-seeking behaviors, suggesting additional mechanisms through which reflexivity may enhance adaptive functioning.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

Beyond confirming the structural validity of the instrument, these findings also carry essential theoretical implications for leadership and organizational research. The present study makes a distinct theoretical contribution by addressing gaps left by existing measures. Most available instruments assess isolated competencies such as self-awareness, communication skills, or feedback-giving style, but they do not capture reflexivity as a multidimensional construct. The RRMQ responds to this limitation by integrating both intrapersonal reflexivity (self-awareness, ethical self-examination) and interpersonal reflexivity (perspective-taking, communication, and mediation) within a single psychometrically validated framework. This integration not only provides a more holistic assessment of reflexive leadership but also offers conceptual clarity for leadership and organizational behavior models. By operationalizing relational reflexivity in multidimensional form, the RRMQ enables future research to test its role as a mediating or moderating variable linking leadership behaviors, team processes, and organizational outcomes.

In this way, the RRMQ surpasses existing single-facet scales by providing a tool that reflects the dialogic and ethical complexity of leadership. Its multidimensional design offers scholars a robust instrument for testing theoretical propositions that require simultaneous consideration of individual and interpersonal reflexivity, thereby advancing the development of integrative models in organizational research. Alongside its theoretical contribution, the RRMQ also provides substantial practical implications for leadership development and managerial practice.

5.2. Practical Implications

Importantly, this study has substantial applied implications. The new instrument can be used not only in academic research on leadership effectiveness but also in practical settings such as development programs, managerial coaching, or leadership competency audits. Applied research has further shown that structured reflexivity interventions can significantly strengthen leadership development initiatives (

Santos et al., 2025). It also offers a foundation for further investigations into the mediating role of reflexivity between leadership behaviors and team outcomes, as suggested by

Lyubovnikova et al. (

2015) and

Rong et al. (

2019).

Beyond organizational practice, the social valence of this research lies in its broader contribution to workplace well-being and societal outcomes. By providing a validated tool to assess relational reflexivity, the RRMQ enables targeted interventions that cultivate respectful dialogue, constructive conflict resolution, and ethical decision-making. These competencies are increasingly recognized as essential for addressing contemporary organizational challenges, such as diversity management, inclusion, and preventing workplace burnout. Recent evidence suggests that structured reflexivity interventions can significantly enhance team performance and leadership development outcomes (

Santos et al., 2025). Systematic reviews also demonstrate that reflexivity is closely tied to emotional regulation and psychological safety at work, both of which are crucial for sustaining and fostering inclusive organizational cultures (

Cova & Farnese, 2025). The ability to measure and strengthen reflexivity supports not only leadership development but also healthier, more inclusive, and more sustainable organizational environments. In turn, these improvements extend beyond organizational boundaries, contributing to social cohesion and to the development of communities that value empathy, dialogue, and ethical responsibility.

Practically, the RRMQ can be applied in recruitment and selection processes to identify candidates with high reflexive capacities, in leadership training programs to assess changes before and after interventions, and in team development initiatives to diagnose specific deficits (e.g., low perspective-taking) that can be addressed with tailored coaching or dialogue-based workshops. In this way, the instrument not only supports scholarly research but also provides managers and HR practitioners with a diagnostic tool for evidence-based development and evaluation.

5.3. Study Limitations

Despite confirming the structural validity of the developed instrument and its consistency with theoretical assumptions, several limitations must be acknowledged.

First, the study used a cross-sectional design. It relied solely on self-report data, which limits causal inference between relational reflexivity and dependent variables such as team effectiveness or leadership quality. Future studies should apply longitudinal designs to assess the temporal stability of reflexivity and its predictive utility.

Second, the current validation was conducted on a student sample, which restricts generalizability. This choice is consistent with recommendations for early-phase scale development (

Kline, 2016;

Worthington & Whittaker, 2006). The use of a homogenous student group also reduces extraneous variance, facilitating more precise assessment of the instrument’s factorial structure at an early stage. Future research should validate the RRMQ in managerial populations, across diverse sectors, and in cross-cultural contexts.

Third, the study did not control for contextual variables such as organizational culture, team type, managerial level, or leadership style. Prior research suggests that structural and interpersonal conditions may moderate the outcomes of reflexivity. Future studies should investigate the model’s generalizability across diverse organizational contexts, including hierarchical, matrixed, and self-managed teams, as well as across various sectors, such as healthcare, education, and technology. It is plausible that reflexivity manifests differently depending on team structure, psychological safety norms, or leadership latitude. Longitudinal or multigroup CFA designs could further assess whether the five-factor structure holds in multinational environments or under varying conditions of cultural tightness and formality.

Fourth, the exclusive use of self-assessment introduces the potential for social desirability bias. Future research should consider triangulating data sources—for example, peer or supervisor ratings—or implementing behavioral assessments.

Fifth, this study primarily established factorial validity but did not assess convergent or discriminant validity. To fully validate the construct of relational reflexivity, future research should examine its relationship with related leadership constructs such as psychological safety, leader–member exchange, or ethical leadership behaviors. Discriminant validity should be tested against unrelated or only loosely associated variables such as assertiveness, extraversion, or general optimism. Establishing such evidence through multitrait–multimethod designs (

Campbell & Fiske, 1959) would significantly strengthen the theoretical integrity and applied utility of the RRMQ, providing stronger convergent and discriminant validation in line with psychometric best practices (

Hair et al., 2010).

Finally, because the instrument relies exclusively on self-report, it is subject to potential social desirability bias. Future studies should triangulate data using multi-source ratings (e.g., peer, subordinate, supervisor evaluations) to strengthen ecological validity. Although such 360° designs represent a distinct line of research that extends beyond the scope of the present validation study, they are worth considering. Moreover, while the CFA subsample (n = 400) was randomly drawn from the same dataset as the EFA sample (N = 524), this procedure does not equate to validation on an independent sample. A fully independent replication is recommended in future research to strengthen generalizability further. Since the sample was drawn from a single institution, external validity is also limited. However, this is unlikely to have affected the internal consistency or factorial structure of the instrument, as homogeneity reduces extraneous variance in early-phase validation. Future studies should replicate the validation of the RRMQ in multi-institutional and cross-cultural samples.

5.4. Future Research

Future research should investigate the relationship between relational reflexivity and both individual and team-level performance indicators, as well as examine the model’s generalizability across various cultural and sectoral contexts. Future studies should extend validation across diverse organizational contexts (e.g., healthcare, education, technology) and test the stability of the five-factor structure in cross-cultural samples. To fully establish construct validity, convergent and discriminant analyses using multitrait–multimethod designs are required. Longitudinal research should also assess the predictive utility of reflexivity for leadership effectiveness and team performance, thereby determining whether the RRMQ can serve as an early diagnostic tool in organizational development.

6. Conclusions

The study achieved its objective by developing and validating the RRMQ, the first multidimensional measure of reflexivity in management. By integrating self-awareness, perspective-taking, communication, conflict resolution, respect, mediation, and intrapersonal reflexivity, the RRMQ provides a psychometrically robust instrument that addresses a critical gap in the leadership literature. Unlike existing single-facet tools, the RRMQ captures reflexivity as both an intrapersonal and interpersonal process, offering scholars a framework to examine its mediating or moderating role in leadership and organizational outcomes.

Practically, the RRMQ can be applied in HR processes such as recruitment and competency audits, in leadership training programs to evaluate pre- and post-changes, and in executive coaching or team development to identify specific reflexivity deficits. These applications extend the tool’s impact beyond academia, supporting evidence-based management and organizational development. These findings confirm the structural validity of the RRMQ in a student sample. However, conclusions should be considered preliminary. Broader validation is required across managerial and intercultural populations, as well as through additional forms of construct validation.