Abstract

Leadership behavior profoundly influences organizational culture, serving as a cornerstone for environments that foster safety, innovation, and employee satisfaction. This article utilizes research from the primary literature to demonstrate how leaders’ actions and underlying fears influence organizational dynamics and employee outcomes, highlighting the importance of respect, transparency, and trust. Studies have shown that leadership styles shape the work environment, driving innovation and performance. However, concerns over productivity, evaluation, and control can lead to poor communication, low transparency, reduced innovation, and diminished performance, creating a culture of mistrust and anxiety. Authoritarian control or neglect of employees’ needs exacerbates these issues, stifling creativity. The Pygmalion and Golem effects demonstrate how positive reinforcement enhances morale, productivity, and retention, while negative reinforcement is detrimental. Leaders operating under fears of failure or loss of control or political capital inadvertently create a culture of fear and increasingly severe feedback loops of reduced employee trust, satisfaction, and commitment. Addressing these fears fosters open communication, psychological safety, transparency, and mutual respect. Strategies for transforming leadership fears into positive change include promoting open communication, decentralizing decision-making, and implementing positive reinforcement mechanisms. Constructive feedback mechanisms encourage bidirectional communication and help mitigate the negative impacts of leadership fears. Leaders who address their fears can strengthen team trust, enhancing collaboration and engagement. Ultimately, managing leadership fears proactively catalyzes organizational learning and development, promoting a mindset where challenges are seen as opportunities for growth. This approach enhances adaptability and resilience while fostering continuous improvement. Addressing leadership fears and fostering a supportive culture is essential for sustainable productivity and success, serving as a starting point for exploring strategies that support employee performance and development, ultimately contributing to organizational success.

1. Introduction

Leadership behavior profoundly influences the development of organizational culture, serving as a cornerstone for establishing an environment that fosters safety, innovation, and employee satisfaction. Previous studies highlighted that leadership’s impact extends across the spectrum of organizational operations, from defining protocols within hierarchical settings to cultivating an atmosphere that encourages creativity and team cohesion. Howard and Ulferts (2017) emphasized the necessity of leadership traits, such as respect, transparency, and trust, in creating a healthy organizational culture. Many other authors identified the interconnection between leadership behavioral style and organizational culture as critical, as Jerab and Mabrouk (2023) note, with leaders defining the work environment, they significantly contribute to the organization’s innovative capabilities and performance levels. This observation was further supported by Semordzi (2018), who investigated the mediatory role of leadership behavior in enhancing job satisfaction through positive organizational culture within academic institutions. Lee (2022) added to these ideas by highlighting how organizational culture bridges leadership style and organizational and employee commitment, underlining the symbiotic relationship between a leader’s approach and the resulting organizational ethos. Given this context, it is unsurprising that leadership fears of low organizational productivity, negative evaluation (poor employee approval ratings), organizational or personal failure, and the loss of control can profoundly impact leadership behavior and organizational culture, leading to environments variously characterized by poor communication, reduced innovation, and diminished overall performance. Leadership styles that emphasize authoritarian control, unpredictability, or lack of consideration for employees’ needs can exacerbate these issues, as they may foster an environment of mistrust and anxiety, further entrenching fear-based behaviors among employees (Savas 2019). Ultimately, dysfunctional leadership behaviors, such as those driven by leaders’ fears of inadequacy or performance failure (of the leader or employee), can negatively impact organizational culture, leading to decreased employee job satisfaction, poorer performance, and higher turnover rates (Agil Panji and Lilik 2022). This “fear-based” leadership approach can diminish employees’ sense of security and belonging and undermine their commitment to the organization (Ilham 2018). Thus, addressing leadership fears related to leaders’ and employees’ capabilities and perceptions and fostering a culture of open communication, psychological safety, transparency, and mutual respect is crucial for enhancing organizational culture and achieving sustainable organizational productivity and success. Despite significant progress, many previous authors emphasize the need for synthesis and further research to understand and mitigate the negative impacts of fear-based leadership behaviors on employee engagement, organizational citizenship, psychological safety, and overall organizational success (Einarsen et al. 2007; Pelletier 2010; Schyns and Schilling 2013; Tepper 2007).

This article explores the importance of leadership approaches to employee relationships, development, and performance through positive and negative reinforcement. It provides an overview of the implications of these approaches, sometimes called the Pygmalion and Golem effects, respectively. It will be shown that positive reinforcement can significantly improve employee morale, productivity, and retention, which are vital for organizational success in a competitive business landscape. The accompanying citations provide an entry point for the reader wishing to learn more. It is not the intent to present all the available literature or understanding of this vast subject, but for this article to serve as a helpful starting point for practitioners wishing to explore effective leadership behavioral strategies for supporting employee performance and development leading to long-term organizational success.

2. Common Leadership Fears

Common fears among organizational leaders, such as fear of failure and loss of employee control, significantly impact decision-making, leadership styles, and the overall organizational culture. Fear of failure, which encompasses the apprehension of not meeting set goals or expectations, can lead to avoidance behaviors, diminishing innovation, and risk-taking within an organization (Cacciotti et al. 2016; Martin and Marsh 2003). This fear often originates from a deep-seated concern over personal and organizational reputation and the potential for financial and social implications of failure (Kollmann et al. 2017; Wisse et al. 2019).

Loss of control relates to leaders’ anxiety over losing their influence or grip on organizational operations, often resulting in micromanagement and a stifling organizational atmosphere (Galford and Drapeau 2003; Ledeen 2004). This control-focused leadership approach can undermine trust and stifle creativity among team members. Fears of leadership or employee incompetency can originate from leaders’ self-doubt about their skills and capabilities and those of employees, often leading to overcompensation by leaders through authoritarian dictatorial and directive management (Hubbart 2024) approaches or avoidance of challenging situations that could expose perceived weaknesses (Meek et al. 2015; Ott and Shafritz 1994). Such fears impact leaders’ effectiveness and contribute to a culture of fear within the organization, where innovation is resisted, and failure is not seen as a learning opportunity but as a threat to be avoided at all costs (Mabrouk 2019; Udovik 2011).

The impact of fear of failure, loss of control, and incompetence on organizational leaders’ decision-making and behavior is profound and multifaceted. These fears can significantly skew leaders’ assessment of risks in decision-making, leading to overly cautious or erroneous decision-making that influences their risk perceptions, affecting their openness to entrepreneurial endeavors and innovation (Cacciotti et al. 2016; Nefzi 2018). This fear can result in decision paralysis, where leaders might avoid making decisions altogether to circumvent the possibility of criticism and failure, or it might prompt them to take unwarranted risks in a bid to avoid perceived threats to their status or power (Kang et al. 2019; Wisse et al. 2019). Similarly, the fear of losing control of employees can drive leaders to adopt a command-and-control style of management, which stifles creativity and autonomy among team members, potentially leading to a culture of compliance rather than innovation (Ledeen 2004; Udovik 2011).

3. The Transmission of Leadership Fears to Organizational Culture

It is helpful to distinguish between organizational climate and culture, as they are often confused but refer to different dimensions of an organization. Organizational culture is the deeply embedded values, beliefs, and norms that define an organization’s identity and shape long-term behaviors and attitudes (Schein 2010). In contrast, organizational climate involves the more immediate, perceptible aspects of the work environment, such as the “mood,” policies, and practices experienced by employees, which can change more frequently (Schneider et al. 2013). While culture is more stable and enduring, climate can shift due to factors like leadership changes or new policies. However, climate and culture are interconnected; a positive climate can reinforce and strengthen a desired culture, while a negative climate can undermine and gradually alter an organization’s cultural values. Shifts in culture can also influence how the organizational climate is perceived and maintained.

Leadership fears are transmitted to organizational culture through various mechanisms, including communication styles, decision-making processes, and establishing organizational policies. Leaders play a pivotal role in shaping the organizational culture by articulating a vision and setting objectives. Their behaviors and the reinforcement mechanisms they employ can either foster a positive culture or transmit their fears, the latter leading to a culture characterized by anxiety and risk aversion (George et al. 1999; Hubbart 2023b). For example, as previously noted, a leadership fear of personal failure may lead to a culture prioritizing risk avoidance over innovation. This often leads to the stifling of creativity and adaptability among employees (Yip et al. 2020). Similarly, leaders’ behaviors driven by fears of employee incompetency or fear of leaders’ loss of control of employees can translate into organizational norms that emphasize strict compliance, centralized decision-making, and a lack of empowerment at lower levels of the organization (Tsai 2011). The resultant culture may be one where employees feel undervalued and restricted, leading to reduced job satisfaction and decreased organizational effectiveness.

Moreover, the interplay between leadership behavior and organizational culture is bidirectional. Said differently, while leadership fears can shape cultural norms, the prevailing culture can also reinforce these fears, creating a feedback cycle that is difficult to break (Giberson et al. 2009; Tsui et al. 2006). For example, organizational cultures that are highly resistant to change may amplify leaders’ fears of losing control, leading them to cling more tightly to established norms and resist necessary evolutions in strategy or operations (Khan et al. 2021). Leadership styles that fail to address or mitigate these cultural characteristics can inadvertently perpetuate an environment where fear dominates rather than trust and innovation. Addressing this cycle requires conscious effort from talented leaders who can understand and reshape the cultural norms that their fears have engendered, promoting values that foster resilience, flexibility, and a more inclusive approach to decision-making (Aktas et al. 2016; Klein et al. 2013). This is particularly important because mismatches between actual and ideal organizational cultures have been associated with stress, sickness, and staff turnover (Hatton et al. 1999). For example, the association between organizational and workplace cultures in the health industry affects patient outcomes, with positive cultures consistently associated with reduced mortality rates, falls, hospital-acquired infections, and increased patient satisfaction (Braithwaite et al. 2017). Similarly, Ho Dai and Huynh Tan (2023) showed that external-oriented flexible, adaptive cultures significantly drive digital transformation (DT) and improve firm performance, while internal-oriented culture does not. Thus, relationship-oriented and participation/representation-oriented leadership positively influences DT, unlike task-oriented leadership. Moreover, emotional cultures within organizations play a crucial role in shaping employee-organization relationships, with cultures of joy and care enhancing trust, satisfaction, and commitment. In contrast, cultures of sadness and fear contribute to emotional exhaustion and stress, resulting in reduced employee performance (Hengen and Alpers 2019; Men and Robinson 2018).

Naturally, one might question whether leadership style influences organizational culture or whether organizational culture influences leadership style. Indeed, the dynamic interplay between leadership style, organizational culture, and change management is critical to an organization’s success, particularly in times of significant transformation. Leadership styles, such as transformational, transactional, and servant leadership, influence organizational culture by setting the tone for workplace values, behaviors, and expectations. Transformational leaders, for example, foster a culture of innovation and shared vision, encouraging creativity and collaboration, whereas transactional leaders create a culture focused on performance and clear expectations (Eagly and Carli 2003). Conversely, organizational culture also affects leadership style by setting norms that guide leaders’ behaviors and decision-making processes. A culture emphasizing collaboration may push leaders towards a participative style, while a more hierarchical culture may favor autocratic leadership (Ogbonna and Harris 2000). Influential leaders recognize this reciprocal relationship and adapt their styles to align with cultural expectations while fostering a culture that supports organizational objectives.

During significant organizational change initiatives, leaders must balance respecting existing cultural norms and driving changes aligning with strategic goals. Successful leaders achieve this by crafting a compelling vision for change that resonates with core cultural values, employing transparent communication to build trust, and engaging employees as active participants in the change process (Hubbart 2023a, 2023b; Tian and Slocum 2016). Leaders can reduce resistance, build commitment, and ensure a smoother transition by aligning their leadership style with the organizational culture and involving employees in decision-making. This approach enables leaders to maintain cultural continuity while strategically guiding the organization toward a successful and sustainable future. It is reasonable to assume that successful organizations are led by leaders who understand the organization’s trajectory, market dynamics, and needs and that, based on this understanding, these leaders significantly influence organizational culture, much like how parents set the tone and culture of a household. Leaders shape organizational culture by establishing norms, values, and practices that align with strategic goals, using leadership styles that fit the organization’s needs, whether fostering collaboration, encouraging innovation, or maintaining a hierarchy (Ogbonna and Harris 2000). By guiding the culture in alignment with external demands and internal objectives, leaders ensure the organization’s success and adaptability in a changing environment (Eagly and Carli 2003). This requires proficient leadership. Without deep organizational understanding and strong leadership skills, leaders may inadvertently contribute to poorer employee performance.

4. The Self-Fulfilling Prophecy of Fear-Based Leadership

The mechanisms through which leadership fears become self-fulfilling prophecies in organizational culture are multifaceted and deeply interwoven. Eden (1992) introduced the concept of the Pygmalion effect in organizations, in which higher expectations from managers regarding subordinate performance can significantly boost subordinate performance. Higher expectations often result in higher employee self-perceptions, resulting in increased confidence, performance, and success, sometimes called the Galatea effect (Eden 1990, 1992).

The concept of the self-fulfilling prophecy (SFP) has its roots in Greek mythology. The tale revolves around Pygmalion, the king of Cyprus, who was renowned as both a sculptor and a misogynist. Pygmalion crafted an ivory statue of a maiden so exquisite that he fell in love with it. He treated the statue as if it were a living being, dressing it in fine clothes and adorning it with jewels. Moved by his devotion and pitying his loneliness, the goddess Aphrodite brought the statue to life. Pygmalion’s belief and treatment of the statue as if it were alive led to its transformation into a living being. The living statue, named Galatea, eventually became Pygmalion’s wife.

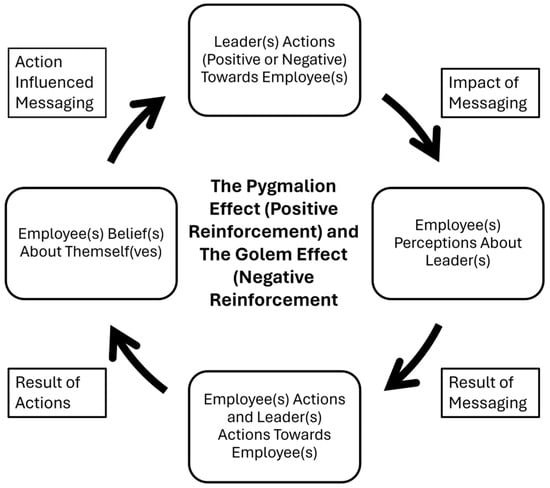

Considered differently, if a manager believes and behaves as if an employee can achieve remarkable things, they are likelier to do so. Conversely, the Golem (or negative) effect refers to the negative version of the Pygmalion or Galatea effect, where low expectations lead to a decrease in performance (Babad et al. 1982; Eden 1990, 1992; Edwards et al. 2002; Rowe and O’Brien 2002). Multiple authors developed conceptual models of the Pygmalion effect (Babad et al. 1982; Eden 1990, 1992; Edwards et al. 2002; Rowe and O’Brien 2002). Field (1989) presented the self-fulfilling prophecy leader, proposing a model where leaders’ expectations can create a group social situation of high expectations, potentially transforming an organizational culture into one that is more energized and positive or, if negative, more fearful and constrained. Figure 1 shows an integrated conceptual model capturing some of the ideas of previous authors but focused on input feedback from leaders to reception and outcomes from subordinates and the circuitous feedback loop that can result in reflecting positive (Pygmalion, Galatea) or negative (Golem) employee productivity and organizational success.

Figure 1.

A feedback system illustrating leader feedback to reception and outcomes of subordinates resulting in positive or negative employee productivity.

The research overwhelmingly underscores the importance of leadership in shaping organizational culture through the expectations they set and the behaviors they model. As noted, leaders who operate under the shadow of their fears, such as the fear of failure or loss of control, can inadvertently instill a culture of fear, reducing trust, satisfaction, and commitment among employees (Hengen and Alpers 2019; Men and Robinson 2018). The evidence is clear that leadership fears significantly influence organizational identity and learning, with ego defenses, like denial and rationalization, maintaining collective self-esteem but often at the expense of necessary change and adaptation (Brown and Starkey 2000). These dynamics illustrate the self-fulfilling nature of leadership fears, where leaders’ negative expectations can lead to behaviors and organizational norms that reinforce those fears, ultimately negatively impacting employee morale, creativity, and productivity. Leader behaviors are critical in this regard because when leaders harbor negative expectations, they can inadvertently communicate a lack of confidence in their employees, undermining their perceived capabilities and reducing their self-efficacy and motivation to perform. Thus, the dynamics (feedback) between leadership expectations and employee performance is not only about completing tasks but extends to the broader psychological impacts on employees, including their sense of self-worth and belonging within an organization (Eden 1992; Field 1989). Research by Manz (1986) on self-leadership and by Eden (1984) on the self-fulfilling prophecy highlighted how employees’ self-perception and motivation are significantly shaped by the cues they receive from their environment, particularly leadership. Negative expectations can diminish employees’ intrinsic motivation and creativity by fostering an environment that lacks psychological safety, where fear of failure overshadows the pursuit of innovation and risk-taking (Brown and Starkey 2000; Men and Robinson 2018). Moreover, the perpetuation of a fear-based culture impacts current employee performance. It can impede the organization’s ability to attract and retain talent, as potential and current employees are deterred by an environment that stifles growth and development (Hengen and Alpers 2019). The aggregate effect of these dynamics underscores the critical importance of talented leadership in understanding organizational development, cultivating positive expectations, and fostering an organizational culture that champions resilience, adaptability, and psychological safety (Agil Panji and Lilik 2022; Hubbart 2023a).

5. Assessing the Impact of Leadership Behavior

Assessing the impact of leadership fears on organizational culture requires a nuanced approach that combines qualitative and quantitative methodologies to capture the breadth and depth of this influence. Tools have been developed that can assist in this endeavor. For example, the Organizational Culture Assessment Instrument (OCAI) facilitates evaluating the prevailing culture within an organization and identifying discrepancies that may be attributed to leadership behaviors and fears (Quinn 2011). Additionally, leadership self-assessment tools that measure aspects like emotional intelligence, transformational leadership qualities, and self-efficacy can provide insights into leaders’ awareness of their fears and their potential impact on the organization (Bass and Avolio 2004; Goleman 1998). Surveys and questionnaires designed to gauge employees’ perceptions of leadership behaviors, such as the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ), can also yield valuable data on how leadership fears are manifested and perceived within a given organization (Bass and Avolio 2004). In addition, qualitative methods, like interviews, focus groups, and employee advocates, may offer a platform for employees to articulate their experiences and observations regarding leadership’s influence on the organizational culture. Ethnographic studies within organizations can uncover the narratives and stories that encapsulate leadership fears and their cultural ramifications (Van Maanen 2011). Social network analysis can illuminate how leadership behaviors influence communication patterns and relationships within the organization, affecting the flow of information and employee engagement (Borgatti and Halgin 2011). By employing a combination of tools and methodologies, organizations can develop a comprehensive understanding of the impact of leadership behaviors on organizational culture and strategize for intervention tactics that foster a positive and supportive culture.

6. The Importance of Transparency and Communication

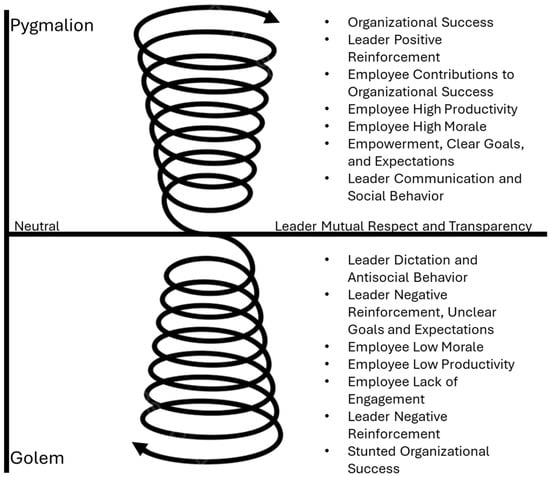

Feedback loops play a pivotal role in illuminating and mitigating the effects of leadership behaviors on organizational culture. These feedback forms can function as diagnostic and corrective mechanisms, highlighting areas where leadership behaviors, driven by underlying fears, negatively impact organizational ethos and provide pathways for change. For example, Edmondson (1999) emphasized psychological safety, crucial in creating an environment where feedback is encouraged and acted upon constructively. These findings align with the work of Kahn (1990), who discussed engagement and disengagement, suggesting that feedback mechanisms can help leaders understand how their behaviors influence employee engagement levels, directly reflecting the organizational culture. Moreover, London and Smither (2002) presented the importance of a feedback-oriented culture in fostering long-term performance management, indicating how structured feedback processes can help leaders align expectations with organizational realities, reducing the gap between fear-driven perceptions and actual employee capabilities. Considering the discussion of the Pygmalion and Golem relationship presented earlier, one can imagine a spectrum of positive to negative leadership behaviors leading to individual and organizational success (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The upward (Pygmalion) and downward (Golem) spiral of positive and negative leadership behaviors, respectively, where a single loop corresponds to the feedback systems illustrated in Figure 1, and subsequent loops build on the cumulative impacts of the previous.

Adopting structured feedback mechanisms, such as 360-degree feedback systems, as highlighted by London and Smither (2002), can offer leaders comprehensive insights into the impact of their behaviors on employees and the broader organizational culture. In so doing, leaders can adjust, if not reverse, their behaviors to better ensure positive employee perceptions (of leadership and the organization) and improve productivity and organizational outcomes. The Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ), described by Bass and Avolio (2004), similarly provides a structured approach to assess leadership styles and their effects on organizational outcomes, including the extent to which leadership behaviors manifest in daily operations. These tools, combined with a commitment to self-leadership and self-awareness (Manz 1986), enable leaders to identify and address the root causes of their fears, fostering a culture of openness, innovation, and resilience. Implementing effective feedback loops requires not only the collection of feedback but also a willingness to engage in reflective practices and act based on the insights gained, thereby breaking negative cycles and potentially negative impacts on organizational culture.

7. Building a Culture of Trust: Empowering Employees

Building an organization’s trust culture is essential for fostering a productive, innovative, and resilient workforce (Hubbart 2023a, 2023b, 2024). Leaders play a crucial role in establishing this culture by empowering employees and decentralizing decision-making. Empowerment begins with trust in employees’ capabilities and judgment, encouraging autonomy and accountability. Leaders can facilitate this by setting clear goals and expectations and providing the resources and support needed for employees to achieve these goals independently (Spreitzer 1995). This approach boosts employees’ confidence in their abilities and reinforces their sense of ownership and commitment to the organization’s success. Promoting a participative leadership style where employees are encouraged to contribute ideas and feedback can further enhance trust and empowerment (Pearce and Conger 2003).

Decentralizing decision-making is a strategy leaders can use to build a culture of trust. By involving employees in the decision-making process, leaders demonstrate trust in their team’s expertise and judgment, which, in turn, fosters a sense of belonging and significance among employees (Carmeli et al. 2009). This inclusion improves the quality of decisions through diverse perspectives and speeds up decision-making as decisions are made closer to the point of action (Barnard 1968). Furthermore, decentralized decision-making encourages a learning environment where mistakes are viewed as opportunities for growth rather than failures, promoting innovation, adaptability, and facilitating growth (Edmondson 1999).

To effectively implement these strategies, leaders must be committed to developing a supportive and transparent communication environment. Open and effective communication allows for the free flow of information and feedback, which is essential for empowerment and effective decentralized decision-making (Mayer et al. 1995; Schein 2010). Additionally, leaders should model the trust and openness they wish to see within their organization, as leadership behavior significantly influences organizational culture (Schein 2010). By embodying these principles, leaders can cultivate a culture of trust that empowers employees, enhances organizational performance, and drives positive change.

8. Case Studies of Transformation and Strategies Employed

Organizations that effectively address and transform leadership fear-based behaviors into positive outcomes often engage in transformative leadership initiatives that lead to practices that foster a culture of psychological safety. For example, companies like Pixar have been celebrated for their culture, which encourages risk-taking and values transparency, allowing for the free exchange of ideas and feedback at all levels. This culture is underpinned by leadership practices that actively seek to learn from failure rather than punish it, thus transforming potential leadership fears that may otherwise stifle innovation and creativity into pillars of organizational success (Catmull 2008; Edmondson 1999). Similarly, Google’s Project Aristotle, which aimed to understand the dynamics of effective teams, described psychological safety as a critical component of high-performing groups. Leaders at Google have since worked to cultivate an environment where employees feel safe to express doubts and concerns, directly addressing potential leadership fears about performance and competition and leveraging these concerns to strengthen team cohesion and innovation (Duhigg 2016). The primary literature reveals that leadership strategies that recognize and address fear-based behaviors, emphasizing open communication, trust, and the value of mistakes as learning opportunities, can transform potential adverse outcomes into a competitive advantage for an organization. Such strategies mitigate the effects of leadership fears and contribute to building a resilient and adaptive organizational culture capable of navigating the challenges of a dynamic business landscape.

9. Synthesis and Future Directions

The preceding text addresses expressed need(s) for ongoing and additional research (Einarsen et al. 2007; Pelletier 2010; Schyns and Schilling 2013; Tepper 2007) by outlining several areas where further exploration is essential to transform fear-based leadership into positive outcomes. There is an emphasis on the importance of cultivating psychological safety, effective communication, and a growth mindset within organizations, suggesting a need for research into how these strategies can be implemented and sustained across different contexts. The text also highlights the necessity of developing leadership skills focused on emotional intelligence, adaptive leadership, and trust-building, pointing to a gap in understanding the most effective training and development methods. Several strategies have been effective for organizations in transforming leadership fears into positive outcomes. Organizations that successfully navigate leadership fear-based behaviors often cultivate a culture of psychological safety, where employees feel safe to take risks, voice their opinions, and admit mistakes without fear of retribution (Edmondson 1999). This culture is complemented by fostering open lines of communication between leaders and employees, ensuring that concerns can be addressed directly and constructively (Men and Stacks 2013). Moreover, adopting a growth mindset at the organizational level encourages continuous learning and development, transforming challenges into opportunities for growth and innovation (Dweck 2006). Recognizing and celebrating successes, even small ones, can help to build a positive organizational culture that counters the paralysis often caused by fear, encouraging a more forward-thinking and proactive approach to leadership and management (Amabile and Kramer 2011). Ultimately, creating a culture of psychological safety is paramount. Edmondson (1999) emphasized that organizations succeed by encouraging open communication and expressing ideas without fear of repercussion. This culture acknowledges fears and vulnerabilities as weaknesses and opportunities for growth and learning. Additionally, empowering employees through decentralizing decision-making enhances organizational resilience and adaptability (Carmeli et al. 2009). Empowered employees are more likely to take initiative and assume responsibility, thereby reducing the burden of fear on leaders and fostering a collective sense of ownership and commitment to organizational goals. Moreover, continuous learning and development, rooted in a growth mindset, equip organizations to view challenges and failures not as threats but as valuable learning opportunities (Dweck 2006). This approach helps mitigate the paralyzing effect of fear by promoting a proactive stance towards problem-solving and innovation. Leaders who engage in self-reflection and seek constructive feedback can better understand the impact of their fears on their leadership style and organizational culture, leading to more informed and effective (Amabile and Kramer 2011; London and Smither 2002) leadership practices. Celebrating big and small successes reinforces positive behaviors and outcomes, embedding a culture of appreciation and achievement (Amabile and Kramer 2011).

Despite extraordinary progress in understanding the effects of a leader’s behavior on employee and organizational success, there remains a significant need for progress. Examples include (but are not limited to) a focus on inherent leadership skills and needs for advancements in leadership development that prioritize emotional intelligence, adaptive leadership, and trust-building, equipping leaders with the abilities and skills to connect authentically with their teams. Real-time feedback mechanisms must be developed to provide continuous insights into leadership behaviors, enabling timely and actionable improvements based on direct human interactions. Advanced diagnostic tools are needed to help leaders identify and address cultural issues, fostering an environment of openness and trust. Platforms that facilitate psychological safety must be developed to encourage secure and open communication, allowing employees to voice their ideas and concerns without fear. Inclusion and equity efforts must advance by creating an inclusive environment through conscious efforts to understand and mitigate biases. Finally, mechanisms to integrate sustainability and social responsibility into core business strategies are necessary to engage employees by aligning organizational goals with employee (and stakeholder) values.

10. Conclusions

This article explores the intricate relationship between leadership fear-based behaviors and organizational culture and success, emphasizing the significant impact of leadership perceptions, expectations, and behaviors on shaping the work environment. Central themes include the mechanisms through which leadership fears manifest within organizations, the pivotal role of feedback loops in reinforcing or mitigating these effects, and the strategies leaders can employ to transform fear into positive organizational change. Key takeaways highlight the importance of fostering a psychological safety and trust culture where employees feel empowered to express ideas, take risks, and learn from failures. Promoting open communication, decentralizing decision-making, and implementing positive reinforcement mechanisms are critical for achieving this cultural shift. Constructive feedback mechanisms, particularly those encouraging a bidirectional flow of communication, are instrumental in identifying and mitigating the negative impacts of leadership fears. Through such mechanisms, organizations can establish positive feedback loops that reinforce trust, engagement, and continuous improvement. Notably, leaders who openly address fears strengthen trust within teams, enhancing communication and collaboration across all organizational levels. Proactively managing leadership fear-based behaviors also catalyzes organizational learning and development, promoting a mindset where challenges are seen as opportunities for learning rather than threats. This perspective enhances an organization’s adaptability and resilience while fostering continuous improvement among employees. Ultimately, the constructive management of leadership fear-based behavior is not merely about alleviating negative emotions, but about using these feelings as catalysts for creating a more dynamic, innovative, and cohesive organizational culture. Leaders who embark on this journey help build organizations better equipped to navigate the complexities of the modern business environment and inspire people to achieve their best professional selves. Future investigations should explore how leadership fear-based behaviors influence organizational culture and success, focusing on feedback loops, strategies for psychological safety, open communication, and positive reinforcement. Importantly, examining the effects of leaders addressing fears on team dynamics, organizational adaptability, and fostering a culture of empowerment, along with longitudinal studies and training program evaluations, is essential for understanding and improving leadership impacts on organizations.

Funding

This work was supported by the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture McIntire Stennis accession number 7003934 and the West Virginia Agricultural and Forestry Experiment Station. The Agriculture and Food Research Initiative supported a portion of this research, Grant No. 2020-68012-31881, from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture. The results presented may not reflect the sponsors’ views, and no official endorsement should be inferred. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, the decision to publish, or the preparation of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

There are no data presented.

Acknowledgments

The author appreciates the feedback of anonymous reviewers, whose constructive comments improved the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Agil Panji, Susilo, and Indayani Lilik. 2022. The Influence of Organizational Culture Leadership Style and Work Stress on Commitment. Indonesian Journal of Law and Economics Review 16: 10-21070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktas, Mert, Michele J. Gelfand, and Paul J. Hanges. 2016. Cultural Tightness–Looseness and Perceptions of Effective Leadership. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 47: 294–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabile, Teresa M., and Steven J. Kramer. 2011. The power of small wins. Harvard Business Review 89: 70–80. [Google Scholar]

- Babad, Elisha Y., Jacinto Inbar, and Robert Rosenthal. 1982. Pygmalion, Galatea, and the Golem: Investigations of biased and unbiased teachers. Journal of Educational Psychology 74: 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnard, Chester I. 1968. The Functions of the Executive. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, vol. 11. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, Bernard M., and Bruce J. Avolio. 2004. Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (TM). Menlo Park: Mind Garden, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Borgatti, Stephen P., and Daniel S. Halgin. 2011. On Network Theory. Organization Science 22: 1168–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braithwaite, Jeffrey, Jessica Herkes, Kristiana Ludlow, Luke Testa, and Gina Lamprell. 2017. Association between organisational and workplace cultures, and patient outcomes: Systematic review. BMJ Open 7: e017708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Andrew D., and Ken Starkey. 2000. Organizational Identity and Learning: A Psychodynamic Perspective. Academy of Management Review 25: 102–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacciotti, Gabriella, James C. Hayton, J. Robert Mitchell, and Andres Giazitzoglu. 2016. A reconceptualization of fear of failure in entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing 31: 302–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeli, Abraham, Daphna Brueller, and Jane E. Dutton. 2009. Learning behaviours in the workplace: The role of high-quality interpersonal relationships and psychological safety. Systems Research and Behavioral Science 26: 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catmull, Edwin. 2008. How Pixar Fosters Collective Creativity. Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Duhigg, Charles. 2016. What Google learned from its quest to build the perfect team. The New York Times Magazine 26: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Dweck, Carol S. 2006. Mindset: The New Psychology of Success. New York: Penguin Random House LLC. [Google Scholar]

- Eagly, Alice H., and Linda L. Carli. 2003. The female leadership advantage: An evaluation of the evidence. The Leadership Quarterly 14: 807–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eden, Dov. 1984. Self-Fulfilling Prophecy as a Management Tool: Harnessing Pygmalion. Academy of Management Review 9: 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eden, Dov. 1990. Pygmalion in Management: Productivity as a Self-Fulfilling Prophecy. Lexington: Lexington Books/DC Heath and Com. [Google Scholar]

- Eden, Dov. 1992. Leadership and expectations: Pygmalion effects and other self-fulfilling prophecies in organizations. The Leadership Quarterly 3: 271–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, Amy. 1999. Psychological Safety and Learning Behavior in Work Teams. Administrative Science Quarterly 44: 350–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, John C., William McKinley, and Gyewan Moon. 2002. The Enactment of Organizational Decline: The Self-Fulfilling Prophecy. The International Journal of Organizational Analysis 10: 55–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einarsen, Ståle, Merethe Schanke Aasland, and Anders Skogstad. 2007. Destructive leadership behaviour: A definition and conceptual model. The Leadership Quarterly 18: 207–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, Richard H. G. 1989. The Self-Fulfilling Prophecy Leader: Achieving the Metharme Effect. Journal of Management Studies 26: 151–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galford, Robert, and Anne Seibold Drapeau. 2003. The enemies of trust. Harvard Business Review 81: 88–95. [Google Scholar]

- George, Gerard, Randall G. Sleeth, and Mark A. Siders. 1999. Organizing Culture: Leader Roles, Behaviors, and Reinforcement Mechanisms. Journal of Business and Psychology 13: 545–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giberson, Tomas R., Christian J. Resick, Marcus W. Dickson, Jacqueline K. Mitchelson, Kenneth R. Randall, and Malissa A. Clark. 2009. Leadership and Organizational Culture: Linking CEO Characteristics to Cultural Values. Journal of Business and Psychology 24: 123–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goleman, Daniel. 1998. Working with emotional intelligence. New York: Bantam, a Division of Penguin Random House LLC. [Google Scholar]

- Hatton, C., M. Rivers, H. Mason, L. Mason, E. Emerson, C. Kiernan, D. Reeves, and A. Alborz. 1999. Organizational culture and staff outcomes in services for people with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 43: 206–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hengen, Kristina M., and Georg W. Alpers. 2019. What’s the Risk? Fearful Individuals Generally Overestimate Negative Outcomes and They Dread Outcomes of Specific Events. Frontiers in Psychology 10: 1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho Dai, Duc, and Khuong Huynh Tan. 2023. The influence of organizational culture and shared leadership on digital transformation and firm performance. Journal of Governance and Regulation/Volume 12: 214–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, Terry L., and Gregory W. Ulferts. 2017. A note on the impact of leadership style on organisational culture. International Journal of Management and Decision Making 16: 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbart, Jason A. 2023a. Organizational Change: Considering Truth and Buy-In. Administrative Sciences 13: 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbart, Jason A. 2023b. Organizational Change: The Challenge of Change Aversion. Administrative Sciences 13: 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbart, Jason A. 2024. Organizational change: Implications of directive change management. Human Resources Management and Services 6: 3457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilham, Romi. 2018. The impact of organizational culture and leadership style on job satisfaction and employee performance. Journal of Advanced Management Science 6: 50–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerab, Daoud A., and Tarek Mabrouk. 2023. The Role of Leadership in Changing Organizational Culture. SSRN Electronic Journal, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, William A. 1990. Psychological Conditions of Personal Engagement and Disengagement at Work. Academy of Management Journal 33: 692–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Xi, Baoshan Zhang, Yanling Bi, and Xiaoxiao Huang. 2019. The effect of malicious envy on the framing effect: The mediating role of fear of failure. Motivation and Emotion 43: 648–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Irfan Ullah, Muhammad Saqib Khan, and Muhammad Idris. 2021. Investigating the support of organizational culture for leadership styles (transformational & transactional). Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment 31: 689–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, Andrew S., Joseph Wallis, and Robert A. Cooke. 2013. The impact of leadership styles on organizational culture and firm effectiveness: An empirical study. Journal of Management & Organization 19: 241–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmann, Tobias, Christoph Stöckmann, and Julia M. Kensbock. 2017. Fear of failure as a mediator of the relationship between obstacles and nascent entrepreneurial activity—An experimental approach. Journal of Business Venturing 32: 280–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledeen, Michael A. 2004. Leadership and the Fear Factor. MIT Sloan Management Review 45: 14–18. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Shih-Nien. 2022. The Mediating Influence of Organizational Culture on Leadership Style and Organizational Commitment. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences 12: 730–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- London, Manuel, and James W. Smither. 2002. Feedback orientation, feedback culture, and the longitudinal performance management process. Human Resource Management Review 12: 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabrouk, Dalia Mohamed Mostafa. 2019. The Dilemma of Guarding Self-Actualization from Fear Claws. Open Journal of Social Sciences 7: 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manz, Charles C. 1986. Self-Leadership: Toward an Expanded Theory of Self-Influence Processes in Organizations. Academy of Management Review 11: 585–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, Andrew J., and Herbert W. Marsh. 2003. Fear of failure: Friend or foe? Australian Psychologist 38: 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, Roger C., James H. Davis, and F. David Schoorman. 1995. An integrative model of organizational trust. The Academy of Management Review 20: 709–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meek, Mariah H., Caitlin Wells, Katharine M. Tomalty, Jaime Ashander, Esther M. Cole, Daphne A. Gille, Breanna J. Putman, Jonathan P. Rose, Matthew S. Savoca, Lauren Yamane, and et al. 2015. Fear of failure in conservation: The problem and potential solutions to aid conservation of extremely small populations. Biological Conservation 184: 209–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Men, Linjuan Rita, and Don W Stacks. 2013. The impact of leadership style and employee empowerment on perceived organizational reputation. Journal of Communication Management 17: 171–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Men, Linjuan Rita, and Katy L. Robinson. 2018. It’s about how employees feel! examining the impact of emotional culture on employee–organization relationships. Corporate Communications: An International Journal 23: 470–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nefzi, Nabiha. 2018. Fear of Failure and Entrepreneurial Risk Perception. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Knowledge 6: 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogbonna, Emmanuel, and Lloyd C. Harris. 2000. Leadership style, organizational culture and performance: Empirical evidence from UK companies. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 11: 766–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, J. Steven, and Jay M. Shafritz. 1994. Toward a Definition of Organizational Incompetence: A Neglected Variable in Organization Theory. Public Administration Review 54: 370–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, Craig L., and Jay A. Conger. 2003. Shared Leadership: Reframing the Hows and Whys of Leadership. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc., pp. 1–18. 334p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelletier, Kathie L. 2010. Leader toxicity: An empirical investigation of toxic behavior and rhetoric. Leadership 6: 373–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, Robert E. 2011. Diagnosing and Changing Organizational Culture: Based on the Competing Values Framework. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe, W. Glenn, and James O’Brien. 2002. The Role of Golem, Pygmalion, and Galatea Effects on Opportunistic Behavior in the Classroom. Journal of Management Education 26: 612–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savas, Ozgur. 2019. Impact of Dysfunctional Leadership on Organizational Performance. Global Journal of Management and Business Research, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schein, Edgar H. 2010. Organizational Culture and Leadership. San Francisco: John Wiley & Sons, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, Benjamin, Mark G. Ehrhart, and William H. Macey. 2013. Organizational Climate and Culture. Annual Review of Psychology 64: 361–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schyns, Birgit, and Jan Schilling. 2013. How bad are the effects of bad leaders? A meta-analysis of destructive leadership and its outcomes. The Leadership Quarterly 24: 138–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semordzi, David Kobla. 2018. Role of leadership behaviour in organizational culture and job satisfaction. European Journal of Business and Management 10: 126–30. [Google Scholar]

- Spreitzer, Gretchen M. 1995. Psychological Empowerment in the Workplace: Dimensions, Measurement, and Validation. Academy of Management Journal 38: 1442–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepper, Bennett J. 2007. Abusive Supervision in Work Organizations: Review, Synthesis, and Research Agenda. Journal of Management 33: 261–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Xiaowen, and John W. Slocum. 2016. Managing corporate social responsibility in China. Organizational Dynamics 45: 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, Yafang. 2011. Relationship between Organizational Culture, Leadership Behavior and Job Satisfaction. BMC Health Services Research 11: 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsui, Anne S., Zhi-Xue Zhang, Hui Wang, Katherine R. Xin, and Joshua B. Wu. 2006. Unpacking the relationship between CEO leadership behavior and organizational culture. The Leadership Quarterly 17: 113–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udovik, Shimon. 2011. Fear and Anxiety: Effective managerial tools or harmful and jeopardizing factors? Far East Journal of Psychology and Business 5: 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Van Maanen, John. 2011. Tales of the Field: On Writing Ethnography. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wisse, Barbara, Diana Rus, Anita C. Keller, and Ed Sleebos. 2019. “Fear of losing power corrupts those who wield it”: The combined effects of leader fear of losing power and competitive climate on leader self-serving behavior. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 28: 742–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yip, Jeremy A., Emma E. Levine, Alison Wood Brooks, and Maurice E. Schweitzer. 2020. Worry at work: How organizational culture promotes anxiety. Research in Organizational Behavior 40: 100124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).