Sustainable Fashion Choices: Exploring European Consumer Motivations behind Second-Hand Clothing Purchases

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Taxonomies of Consumer Motivations in the Second-Hand Clothing Market

2.2. Economic Motivations

2.3. Hedonic Motivations

2.4. Ethical Motivations

2.5. Fashion Interest and Other Motivations

3. The Research Method

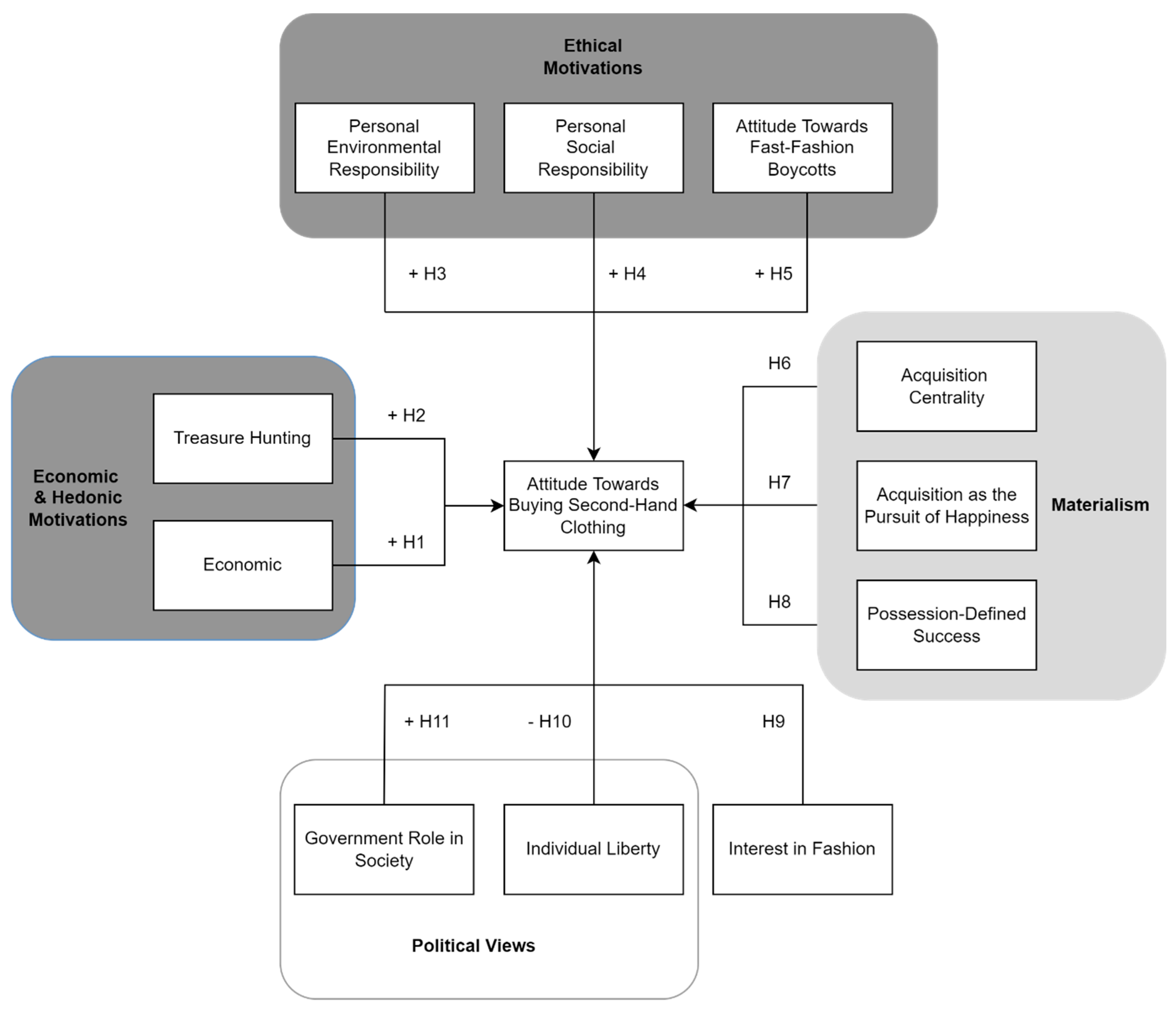

3.1. The Conceptual Model

3.2. Measurement Scales

3.3. Statistical Analysis

4. Research Results

4.1. Sample Characteristics

4.2. Exploratory and Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4.3. Ordinary Least Squares Regression

5. Discussion, Contributions, and Limitations

5.1. Discussion

5.2. Theoretical and Practical Contributions

5.3. Limitations

5.4. Further Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Amed, Imran, Achim Berg, Anita Balchandani, Sarah André, Sandrine Devillard. Michael Straub, Felix Rölkens, Joëlle Grunberg, Janet Kersnar, and Hannah Crump. 2022. McKinsey. The State of Fashion 2023. Holding Onto Growth as Global Clouds Gather. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/retail/our-insights/state-of-fashion-archive#section-header-2023 (accessed on 7 August 2024).

- Arora, Nidhi, Tamara Charm, Anne Grimmelt, Mianne Ortega, Kelsey Robinson, Christina Sexauer, Yvonne Staack, Scott Whitehead, and Naomi Yamakawa. 2020. McKinsey. A Global View of How Consumer Behavior Is Changing Amid COVID-19. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/growth-marketing-and-sales/our-insights/a-global-view-of-how-consumer-behavior-is-changing-amid-covid-19 (accessed on 7 August 2024).

- Bagatini, Francine Z., Eduardo Rech, Natalia A. Pacheco, and Leonardo Nicolao. 2023. Can you imagine yourself wearing this product? Embodied mental simulation and attractiveness in e-commerce product pictures. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing 17: 470–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardhi, Fleura, and Eric J. Arnould. 2005. Thrift shopping: Combining utilitarian thrift and hedonic treat benefits. Journal of Consumer Behaviour: An International Research Review 4: 223–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, Russell W., John F. Sherry, and Melanie Wallendorf. 1988. A Naturalistic Inquiry into Buyer and Seller Behavior at a Swap Meet. Journal of Consumer Research 14: 449–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilro, Ricardo G., and Sandra Maria Correia Loureiro. 2023. I am feeling so good! Motivations for interacting in online brand communities. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing 17: 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borusiak, Barbara, Andrzej Szymkowiak, David L. Lluch, and Paula Sánchez-Bravo. 2021. The role of environmental concern in explaining attitude towards second-hand shopping. Entrepreneurial Business and Economics Review 9: 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burman, Ritika, Yizhuo Chen, and Yingijao Xu. 2013. Exploring College Student’s Shopping Motivation for Secondhand Clothing. Paper presented at International Textile and Apparel Association (ITAA) Annual Conference Proceedings, New Orleans, LA, USA, October 15–18; Ames: Iowa State University. [Google Scholar]

- Caro, Felipe, and Victor Martínez-de-Albéniz. 2015. Fast Fashion: Business Model Overview and Research Opportunities. In Retail Supply Chain Management: Quantitative Models and Empirical Studies, International Series in Operations Research & Management Science. Edited by Narenda Agrawal and Stephen A. Smith. Boston: Springer US, pp. 237–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervellon, Marie-Cécile, Lindsey Carey, and Trine Harms. 2012. Something old, something used: Determinants of women’s purchase of vintage fashion vs. second-hand fashion. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 40: 956–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, Breno de Paula A. 2016. Social Boycott. Review of Business Management 19: 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLong, Marilyn, Barbara Heinemann, and Kathryn Reiley. 2005. Hooked on Vintage! Fashion Theory 9: 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinh, Thi Cam Tu, and Yoonjae Lee. 2022. “I want to be as trendy as influencers”—how “fear of missing out” leads to buying intention for products endorsed by social media influencers. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing 16: 346–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domina, Tanya, and Kathryn Koch. 2007. Environmental profiles of female apparel shoppers in the Midwest, USA. Journal of Consumer Studies & Home Economics 22: 147–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ek Styvén, Maria, and Marcello M. Mariani. 2020. Understanding the intention to buy secondhand clothing on sharing economy platforms: The influence of sustainability, distance from the consumption system, and economic motivations. Psychology & Marketing 37: 724–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feick, Lawrence F., Linda L. Price, and Audrey G. Federouch. 1988. Coupon Giving: Feeling Good by Getting a Good Deal for Somebody Else. Working Paper. Pittsburgh: Grad. Sch. of Business, University of Pittsburgh. [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro, Carla, Sean Sands, and Jan Brace-Govan. 2016. The role of fashionability in second-hand shopping motivations. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 32: 262–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frau, Moreno, Francesca Cabiddu, Luca Frigau, Przemysław Tomczyk, and Francesco Mola. 2023. How emotions impact the interactive value formation process during problematic social media interactions. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing 17: 773–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, Monroe. 1985. Consumer Boycotts in the United States, 1970–1980: Contemporary Events in Historical Perspective. Journal of Consumer Affairs 19: 96–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerval, Olivier. 2010. Fashion: Concept to Catwalk, Illustrated ed. Buffalo: Firefly Books, Richmond Hill, Ont. [Google Scholar]

- Gilal, Faheem G., Abdul R. Shaikh, Zhiyong Yang, Rukhsana G. Gilal, and Naeem G. Gilal. 2024. Secondhand consumption: A systematic literature review and future research agenda. International Journal of Consumer Studies 48: e13059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregersen, Thea, Rouven Doran, Gisela Böhm, Endre Tvinnereim, and Wouter Poortinga. 2020. Political Orientation Moderates the Relationship Between Climate Change Beliefs and Worry About Climate Change. Frontiers in Psychology 11: 1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregson, Nicky, and Louise Crewe. 1997. The Bargain, the Knowledge, and the Spectacle: Making Sense of Consumption in the Space of the Car-Boot Sale. Environment and Planning D 15: 87–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, Neil, and Solon Simmons. 2014. Professors and Their Politics. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-1-4214-1334-1. [Google Scholar]

- Guiot, Denis, and Dominique Roux. 2010. A second-hand shoppers’ motivation scale: Antecedents, consequences, and implications for retailers. Journal of Retailing 86: 355–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, Shruti, and Denise T. Ogden. 2009. To buy or not to buy? A social dilemma perspective on green buying. Journal of Consumer Marketing 26: 376–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, Joseph F., William C. Black, Barry J. Babin, and Rolph E. Anderson. 2014. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed. Pearson New International Edition. Harlow: Pearson Education Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Harper, Craig A., and Darren Rhodes. 2021. Reanalysing the factor structure of the moral foundations questionnaire. British Journal of Social Psychology 60: 1303–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Ling, Wenkai Zhou, Zhuoyi Ren, and Zhilin Yang. 2022. Make the apps stand out: Discoverability and perceived value are vital for adoption. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing 16: 494–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczmarek, Łukasz D. 2017. Hedonic Motivation. In Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences. Edited by Virgil Zeigler-Hill and Todd K. Shackelford. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiehn, Katharina, and Antonia W. Vojkovic. 2018. Millennials Motivations for Shopping Second-Hand Clothing as Part of a Sustainable Consumption Practice. Boras: The Swedish School of Textiles. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Shina, Eunju Ko, and Sang Jin Kim. 2018. Fashion brand green demarketing: Effects on customer attitudes and behavior intentions. Journal of Global Fashion Marketing 9: 364–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, Philip, and Sidney J. Levy. 1971. Demarketing, yes, demarketing. Harvard Business Review 79: 74–80. [Google Scholar]

- Laitala, Kirsi, and Ingun G. Klepp. 2018. Motivations for and against second-hand clothing acquisition. Clothing Cultures 5: 247–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, Chen, and Shupei Yuan. 2019. Influencer marketing: How message value and credibility affect consumer trust of branded content on social media. Journal of Interactive Advertising 19: 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mano, Haim, and Michael T. Elliott. 1997. Smart Shopping: The Origins and Consequences of Price Savings. Advances in Consumer Research 24: 504. [Google Scholar]

- Maslow, Abraham H. 1970. Motivation and Personality. Manhattan: Harper & Row. [Google Scholar]

- McNeill, Lisa, and Rebecca Moore. 2015. Sustainable fashion consumption and the fast fashion conundrum: Fashionable consumers and attitudes to sustainability in clothing choice. International Journal of Consumer Studies 39: 212–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Cass, Aron, and Vida Siahtiri. 2013. In search of status through brands from Western and Asian origins: Examining the changing face of fashion clothing consumption in Chinese young adults. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 20: 505–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ögel, İlkin Y. 2022. Is it sustainability or fashion? Young consumers’ motivations for buying second-hand clothing. Business & Management Studies: An International Journal 10: 817–34. [Google Scholar]

- Padmavathy, Chandrasekaran, M. Swapana, and Justin Paul. 2019. Online second-hand shopping motivation–Conceptualization, scale development, and validation. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 51: 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Hyun J., and Li M. Lin. 2020. Exploring attitude–behavior gap in sustainable consumption: Comparison of recycled and upcycled fashion products. Journal of Business Research 117: 623–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebouças, Raquel, and Ana M. Soares. 2021. Voluntary simplicity: A literature review and research agenda. International Journal of Consumer Studies 45: 303–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richins, Marsha L., and Scott Dawson. 1992. A consumer values orientation for materialism and its measurement: Scale development and validation. Journal of Consumer Research 19: 303–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbandeh, Mahsa, and Tuğba Şabanoğlu. 2022. Secondhand Apparel. A Statista Dossierplus on the Secondhand Apparel Market and the Growth of the Resale Segment. Available online: https://www.statista.com/study/116165/secondhand-apparel/ (accessed on 7 August 2024).

- Shaw, Deirdre, and Terry Newholm. 2002. Voluntary simplicity and the ethics of consumption. Psychology & Marketing 19: 167–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherry, John F. 1990. A Sociocultural Analysis of a Midwestern American Flea Market. Journal of Consumer Research 17: 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soiffer, Stephen S., and Gretchen M. Herrmann. 1987. Visions of power: Ideology and practice in the American garage sale. The Sociological Review 35: 48–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, Jonathan, Suzanne Horne, and Saily Hibbert. 1996. Car boot sales: A study of shopping motives in an alternative retail format. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 24: 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudbury-Riley, Lynn, and Florian Kohlbacher. 2016. Ethically minded consumer behavior: Scale review, development, and validation. Journal of Business Research 69: 2697–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Shirley, and Peter A. Todd. 1995. Understanding Information Technology Usage: A Test of Competing Models. Information Systems Research 6: 144–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Ethical Consumer Group. 2022. H&M | Shop Ethical! Company Profile [WWW Document]. Available online: https://guide.ethical.org.au/company/?company=5207 (accessed on 27 December 2022).

- thredUP. 2023. 2023 Resale Market and Consumer Trend Report [WWW Document]. Available online: https://www.thredup.com/resale (accessed on 24 June 2023).

- Wagner, Melisa M., and Tincuta Heinzel. 2020. Human Perceptions of Recycled Textiles and Circular Fashion: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 12: 10599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Bairong, Yuxuan Fu, and Yong Li. 2022. Young consumers’ motivations and barriers to the purchase of second-hand clothes: An empirical study of China. Waste Management 143: 157–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wąsowicz-Zaborek, Elżbieta. 2018. Influence of national culture on website characteristics in international business. International Entrepreneurship Review 4: 421. [Google Scholar]

- Wąsowicz-Zaborek, Elżbieta. 2020. Cultural determinants of social media use in world markets. Folia Oeconomica Stetinensia 20: 423–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, Colin C., and Carole Paddock. 2003. The Meanings of Informal and Second-Hand Retail Channels: Some Evidence from Leicester. International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research 13: 317–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witek-Hajduk, Marzanna K., Anna M. Grudecka, and Anna Napiórkowska. 2022. E-commerce in the internet-enabled foreign expansion of Polish fashion brands owned by SMEs. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal 26: 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wooldridge, Jeffrey M. 2019. Introductory Econometrics: A Modern Approach, 7th ed. Boston: Cengage Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Yingjiao, Yizhuo Chen, Ritika Burman, and Hongshan Zhao. 2014. Second-hand clothing consumption: A cross-cultural comparison between American and Chinese young consumers. International Journal of Consumer Studies 38: 670–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Ruoh-Nan, Su Yun Bae, and Huimin Xu. 2015. Second-hand clothing shopping among college students: The role of psychographic characteristics. Young Consumers 16: 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Hye J., Yoon-Joo Lee, Shuoya Sun, and Jinho Joo. 2023. Does congruency matter for online green demarketing campaigns? Examining the effects of retargeting display ads embedded in different browsing contexts. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing 17: 882–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaborek, Piotr. 2016. Elements of Marketing Research. Warsaw: Warsaw School of Economics Press. ISBN 978-83-65416-34-6. [Google Scholar]

- Zahid, Nawaz M., Jashim Khan, and Meng Tao. 2023. Exploring mindful consumption, ego involvement, and social norms influencing second-hand clothing purchase. Current Psychology 42: 13960–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Jing, Linghua Zhang, and Bei Ma. 2023. Ride-sharing platforms: The effects of online social interactions on loyalty, mediated by perceived benefits. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing 17: 698–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Item | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Materialism (Possession-defined Success) | Mat_suc1. I admire people who own expensive homes, cars, and clothes. | Richins and Dawson (1992) |

| Mat_suc2. Some of the most important achievement in life include acquiring material possessions. | ||

| Mat_suc3. I don’t place much emphasis on the amount of material objects people own as a sign of success. * | ||

| Mat_suc4. The things I own say a lot about how well I’m doing in life. | ||

| Mat_suc5. I like to own things that impress people. | ||

| Mat_suc6. I don’t pay much attention to the material objects other people own. * | ||

| Materialism (Acquisition Centrality) | Mat_cen1. I usually buy only the things I need. * | |

| Mat_cen2. I try to keep my life simple, as far as possessions are concerned. * | ||

| Mat_cen3. The things I own aren’t all that important to me. * | ||

| Mat_cen4. I enjoy spending money on things that aren’t practical. | ||

| Mat_cen5. Buying things gives me a lot of pleasure. | ||

| Mat_cen6. I like a lot of luxury in my life. | ||

| Mat_cen7. I put less emphasis on material things than most people I know. * | ||

| Materialism (Acquisition as the Pursuit of Happiness) | Mat_hap1. I have all the things I really need to enjoy my life. * | |

| Mat_hap2. My life would be better if I owned certain things I don’t have. | ||

| Mat_hap3. I wouldn’t be any happier if I owned nicer things. * | ||

| Mat_hap4. I’d be happier if I could afford to buy more things. | ||

| Mat_hap5. It sometimes bothers me quite a bit that I can’t afford to buy all the things I’d like. | ||

| Interest in Fashion | Fas1. I keep up-to-date with the changing (i.e., latest) fashions | O’Cass and Siahtiri (2013) |

| Fas2. The latest fashionable, attractive styling is important to me | ||

| Fas3. I generally try to keep up to date with the latest fashions | ||

| Fas4. I am fashion conscious | ||

| Political Views (Individual Liberty) | Pol1. Society works best when it lets individuals take responsibility for their own lives without telling them what to do. | Harper and Rhodes (2021) |

| Pol2. I think everyone should be free to do as they choose, so long as they don’t infringe upon the equal freedoms of others. | ||

| Pol3. People who are successful in business have a right to enjoy their wealth as they see fit. | ||

| Pol4. The government interferes far too much in our everyday lives | ||

| Pol5. The government should do more to advance the common good, even if that means limiting the freedom and choices of individuals. * | ||

| Political Views (Government’s Role in Society) | Pol6. The government should do more to help needy people, even if it means going deeper into debt. | Gross and Simmons (2014) |

| Pol7. The government should see to it that every person has a job and a good standard of living. | ||

| Pol8. Business corporations make too much profit. | ||

| Attitude towards second-hand clothing shopping | Att1. I like the idea the idea of buying second-hand clothes | Adapted from: Taylor and Todd (1995)—THB |

| Att2. Purchasing second-hand clothes is a good idea | ||

| Att3. I have a good attitude towards using second-hand clothes | ||

| Economic Motivation | Ecn1. I can afford more clothes because I pay less second-hand | Guiot and Roux (2010) |

| Ecn2. One can have more clothes for the same amount of money if one buys second-hand | ||

| Ecn3. I feel that I have lots of clothes for not much money by buying them second-hand | ||

| Ecn4. I don’t want to pay more for the piece of clothes just because it’s new | ||

| Ecn5. By buying second-hand, I feel I’m paying a fair price for clothes | ||

| Treasure Hunting Motivation | Tre1. I like wandering around second-hand outlets because I always hope I’ll come across a real find | |

| Tre2. I go to certain second-hand outlets to rummage around and try to find something | ||

| Tre3. I’m often on the look-out for a find when I go to certain second-hand outlets | ||

| Tre4. In certain second-hand outlets, I feel rather like a treasure hunter | ||

| Personal social responsibility | Res_soc1. I will not buy clothes if I know that the company that sells it is socially irresponsible | Adapted from Sudbury-Riley and Kohlbacher (2016) |

| Res_soc2. I do not buy clothes from companies that I know use sweatshop labor, child labor, or other poor working conditions. | ||

| Res_soc3. I have paid more for socially responsible products when there is a cheaper alternative | ||

| Personal environmental responsibility | Res_env1. When there is a choice, I always choose clothes that contribute to the least amount of environmental damage | |

| Res_env2. I have switched to second-hand clothes for environmental reasons | ||

| Res_env3. If I understand the potential damage to the environment that some clothes can cause, I do not purchase those clothes | ||

| Res_env4. I have paid more for environmentally friendly clothes when there is a cheaper alternative. | ||

| Attitude towards fast-fashion boycotts | Boy1. To abstain from buying clothes from fast fashion shops is a very efficient way to make a company change its actions | Adapted from Cruz (2016) |

| Boy2. I would feel guilty if I bought fast fashion clothes | ||

| Boy3. Everyone should stop buying fast fashion clothes, because every contribution, no matter how small, is very important | ||

| Boy4. I would feel uncomfortable if the people that abstain from buying fast fashion products would see me buying or wearing them | ||

| Boy5. As I don’t buy many fast fashion clothes, my boycotting would not me significant | ||

| Boy6. By boycotting, I can help make fast fashion companies change their decision |

| Gender | Age | Country of Residence | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 74% | <16 | 0% | Poland | 41.70% | Armenia | 0.40% |

| Male | 22% | 16–20 | 12% | Switzerland | 22.40% | Canada | 0.40% |

| Non-binary/third | 2% | 21–25 | 41% | Germany | 9.40% | Czech Republic | 0.40% |

| Prefer not to say | 1% | 26–30 | 11% | Romania | 5.10% | Hungary | 0.40% |

| 31–35 | 13% | France | 3.90% | Italy | 0.40% | ||

| 36–40 | 7% | Netherlands | 3.90% | Russia | 0.40% | ||

| 41–45 | 6% | United Kingdom | 2.80% | Slovakia | 0.40% | ||

| 46–50 | 4% | Georgia | 1.20% | Spain | 0.40% | ||

| 51–55 | 3% | Sweden | 0.80% | United States | 0.40% | ||

| 56–60 | 2% | Belgium | 0.80% | Vietnam | 0.40% | ||

| >60 | 1% | Denmark | 0.40% | ||||

| Assessment of personal financial situation | |||||||

| Education | Because of my money situation, I feel like I will never have the things I want in my life. | ||||||

| Less than High School | 1% | Strongly disagree | 15% | ||||

| High School graduate | 19% | Disagree | 42% | ||||

| Bachelor’s degree | 40% | Somewhat disagree | 25% | ||||

| Master’s degree | 35% | Somewhat agree | 13% | ||||

| Professional degree | 3% | Agree | 4% | ||||

| Doctoral degree | 1% | Strongly agree | 2% | ||||

| I prefer not to say | 2% | ||||||

| Assessment of personal financial situation | |||||||

| I can enjoy my life because of the way I’m managing my money. | I could easily handle an unexpected expense of USD 300. | I have money left at the end of the month. | |||||

| Strongly disagree | 1% | Strongly disagree | 6% | Strongly dis. | 3% | ||

| Disagree | 6% | Disagree | 13% | Disagree | 9% | ||

| Somewhat disagree | 15% | Somewhat disagree | 12% | Somewhat dis. | 8% | ||

| Somewhat agree | 33% | Somewhat agree | 25% | Somewhat agr. | 22% | ||

| Agree | 36% | Agree | 26% | Agree | 36% | ||

| Strongly agree | 10% | Strongly agree | 18% | Strongly agr. | 22% | ||

| Declared SHC shopping behavior | |||||||

| Other types of SH goods normally bought | Place of SHC shopping | ||||||

| Shoes | 31% | Specialized SH shops | 74% | ||||

| Books, movies, music and games | 55% | Peer-to-peer platforms | 37% | ||||

| Bags and Accessories | 52% | Markets and bazaars | 24% | ||||

| Consumer electronics | 25% | Family and friends | 22% | ||||

| Furniture and household goods | 48% | Other | 4% | ||||

| Household appliances | 20% | ||||||

| Toys and baby products | 16% | ||||||

| Other | 6% | ||||||

| SHC budget (from | SHC spendings | Shopping Frequency | Last time of SHC shopping | ||||

| monthly clothing budget) | last month | ||||||

| <20% | 67% | <EUR 10 | 56% | 2–4 a week | 1% | <4 days | 11% |

| 21–40% | 9% | EUR 10–EUR 25 | 24% | 1 a week | 6% | <7 days | 9% |

| 41–60% | 9% | EUR 26–EUR 50 | 11% | 1 a month | 25% | <1 month | 25% |

| 61–80% | 7% | EUR 51–EUR 100 | 6% | 1 every few months | 43% | <few months | 27% |

| 81–100% | 7% | EUR 101–EUR 200 | 1% | 1 every few years | 20% | <1 year | 12% |

| >EUR 200 | 2% | Never | 5% | <few years | 12% | ||

| Never | 4% | ||||||

| Rspnsb | Mtrlzm | Hedonc | Fashin | Attitd | Econmc | Pltcl1 | Pltcl2 | Mtrlsm | Income | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Res_soc2 | 0.690 | |||||||||

| Res_env1 | 0.802 | |||||||||

| Res_env3 | 0.842 | |||||||||

| Boy2 | 0.621 | |||||||||

| Mat_suc2 | 0.509 | |||||||||

| Mat_hap2 | 0.811 | |||||||||

| Mat_hap3 | −0.703 | |||||||||

| Mat_hap4 | 0.761 | |||||||||

| Tre1 | 0.833 | |||||||||

| Tre2 | 0.879 | |||||||||

| Tre3 | 0.914 | |||||||||

| Tre4 | 0.740 | |||||||||

| Fas1 | 0.883 | |||||||||

| Fas2 | 0.861 | |||||||||

| Fas3 | 0.934 | |||||||||

| Att1 | 0.934 | |||||||||

| Att2 | 0.830 | |||||||||

| Att3 | 0.856 | |||||||||

| Ecn1 | 0.834 | |||||||||

| Ecn2 | 0.765 | |||||||||

| Ecn3 | 0.788 | |||||||||

| Pol1 | 0.769 | |||||||||

| Pol2 | 0.735 | |||||||||

| Pol3 | 0.579 | |||||||||

| Pol6 | 0.678 | |||||||||

| Pol7 | 0.714 | |||||||||

| Pol8 | 0.647 | |||||||||

| Mat_cen1 | 0.835 | |||||||||

| Mat_cen2 | 0.775 | |||||||||

| Mat_cen5 | −0.587 | |||||||||

| Inc1 | 0.709 | |||||||||

| Inc2 | 0.698 | |||||||||

| Inc4 | 0.761 | |||||||||

| Indicator | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | SPMR | ||||||

| Value | 0.942 | 0.932 | 0.045 | 0.062 |

| SHC Attitude | SHC Attitude | SHC Attitude | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | Estimates | p | Estimates | p | Estimates | p |

| (Intercept) | 0.00 (−0.08–0.08) | 1.000 | −0.17 (−0.46–0.11) | 0.230 | −0.25 (−0.54–0.04) | 0.094 |

| economic | 0.20 (0.11–0.30) | <0.001 | 0.19 (0.09–0.29) | <0.001 | 0.29 (0.05–0.52) | 0.016 |

| hedonic | 0.39 (0.30–0.47) | <0.001 | 0.40 (0.31–0.49) | <0.001 | 0.37 (0.28–0.45) | <0.001 |

| responsibility | 0.16 (0.04–0.28) | 0.011 | 0.16 (0.03–0.29) | 0.020 | 0.23 (0.11–0.36) | <0.001 |

| materialism1 | −0.05 (−0.14–0.05) | 0.329 | −0.03 (−0.13–0.08) | 0.623 | −0.05 (−0.15–0.05) | 0.310 |

| materialism2 | −0.17 (−0.33–−0.02) | 0.029 | −0.17 (−0.35–0.00) | 0.051 | −0.38 (−0.87–0.11) | 0.127 |

| fashion | −0.12 (−0.20–−0.04) | 0.003 | −0.12 (−0.20–−0.04) | 0.005 | −0.14 (−0.21–−0.06) | 0.001 |

| political1 | −0.13 (−0.24–−0.03) | 0.014 | −0.11 (−0.23–0.00) | 0.052 | −0.08 (−0.19–0.03) | 0.144 |

| political2 | 0.05 (−0.09–0.18) | 0.495 | 0.03 (−0.12–0.18) | 0.702 | 0.23 (−0.01–0.47) | 0.065 |

| income | 0.09 (−0.01–0.19) | 0.064 | 0.10 (−0.00–0.21) | 0.054 | 0.12 (0.02–0.23) | 0.016 |

| age | −0.07 (−0.17–0.03) | 0.172 | 0.09 (−0.09–0.28) | 0.323 | ||

| gender | 0.13 (−0.09–0.35) | 0.251 | 0.24 (0.02–0.45) | 0.034 | ||

| country | 0.02 (−0.16–0.20) | 0.845 | 0.09 (−0.07–0.26) | 0.280 | ||

| education | 0.07 (−0.17–0.31) | 0.571 | 0.04 (−0.18–0.27) | 0.708 | ||

| materialism1 × fashion | 0.12 (0.06–0.19) | <0.001 | ||||

| materialism2 × age | −0.24 (−0.40–−0.08) | 0.003 | ||||

| responsibility × political1 | −0.18 (−0.33–−0.03) | 0.017 | ||||

| political2 × gender | −0.30 (−0.55–−0.05) | 0.019 | ||||

| age × gender | −0.27 (−0.48–−0.06) | 0.012 | ||||

| materialism2 × education | 0.56 (0.13–0.99) | 0.011 | ||||

| economic × age | 0.16 (0.06–0.26) | 0.002 | ||||

| economic × materialism2 | 0.17 (0.03–0.30) | 0.017 | ||||

| economic × materialism1 | 0.06 (−0.01–0.14) | 0.111 | ||||

| materialism2 × political1 | −0.25 (−0.44–−0.05) | 0.015 | ||||

| economic × education | −0.19 (−0.43–0.05) | 0.123 | ||||

| political1 × age | −0.16 (−0.28–−0.03) | 0.013 | ||||

| hedonic × political1 | 0.09 (−0.00–0.19) | 0.061 | ||||

| political2 × income | −0.15 (−0.28–−0.01) | 0.034 | ||||

| fashion × political2 | 0.19 (0.10–0.28) | <0.001 | ||||

| hedonic × political2 | −0.15 (−0.24–−0.06) | 0.001 | ||||

| materialism1 × income | −0.12 (−0.22–−0.02) | 0.021 | ||||

| materialism1 × materialism2 | −0.10 (−0.24–0.04) | 0.164 | ||||

| political1 × political2 | −0.17 (−0.33–−0.00) | 0.049 | ||||

| materialism2 × gender | −0.29 (−0.66–0.08) | 0.123 | ||||

| economic × income | −0.10 (−0.19–−0.00) | 0.044 | ||||

| responsibility × income | 0.11 (−0.02–0.24) | 0.088 | ||||

| Observations | 254 | 240 | 240 | |||

| R2/R2 adjusted | 0.549/0.532 | 0.558/0.533 | 0.704/0.653 | |||

| Predictor | Relevant Hypothesis | Equations for Regression Parameters Describing Conditional Effects of Predictors on the Outcome Variable | Minimum Regression Weight | Maximum Regression Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic | H1 | (0.29 + 0.16 ∗ age + 0.17 ∗ materialism2 + 0.06 ∗ materialism1 − 0.19 ∗ education − 0.1 ∗ income) ∗ economic | −0.39 | 0.58 |

| Hedonic | H2 | (0.37 + 0.09 ∗ political1 − 0.15 ∗ political2) ∗ hedonic | 0.13 | 0.61 |

| Responsibility | H3, H4, H5 | (0.23 − 0.18 ∗ political1 + 0.11 ∗ income) ∗ responsibility | −0.06 | 0.52 |

| Materialism1 | H6 | (−0.05 + 0.12 ∗ fashion + 0.06 ∗ economic − 0.12 ∗ income − 0.1 ∗ materialism2) ∗ materialism1 | −0.45 | 0.35 |

| Materialism2 | H7, H8 | (−0.38 − 0.24 ∗ age + 0.56 ∗ education + 0.17 ∗ economic − 0.25 ∗ political1 − 0.1 ∗ materialism1 − 0.29 ∗ gender) ∗ materialism2 | −1.99 | 0.94 |

| Fashion | H9 | (−0.14 + 0.12 ∗ materialism1 + 0.19 ∗ political2) ∗ fashion | −0.45 | 0.17 |

| Political1 | H10 | (−0.08 − 0.18 ∗ responsibility − 0.16 ∗ age + 0.09 ∗ hedonic − 0.17 ∗ political2) ∗ political1 | −0.68 | 0.52 |

| Political2 | H11 | (0.23 − 0.3 ∗ gender − 0.15 ∗ income + 0.19 ∗ fashion − 0.15 ∗ hedonic − 0.17 ∗ political1) ∗ political2 | −0.73 | 0.89 |

| Income | (0.12 − 0.15 ∗ political2 − 0.12 ∗ materialism1 − 0.1 ∗ economic + 0.11 ∗ responsibility) ∗ income | −0.36 | 0.6 | |

| Age | (0.09 − 0.24 ∗ materialism2 − 0.27 ∗ gender + 0.16 ∗ economic − 0.16 ∗ political1) ∗ age | −0.74 | 0.65 | |

| Gender | (0.24 − 0.3 ∗ political2 − 0.27 ∗ age − 0.29 ∗ materialism2) ∗ gender | −0.62 | 1.1 | |

| Country | 0.09 ∗ Country | 0.09 | 0.09 | |

| Education | (0.04 + 0.56 ∗ materialism2 − 0.19 ∗ economic) ∗ education | −0.71 | 0.79 |

| Hypothesis | Verification Outcome | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| H1 | Supported | Economic motivation is positively correlated with the attitude towards buying SHC, particularly when moderating variables are close to their mean values. This motivation may have a stronger effect for individuals who are older, less educated, in an unfavorable financial situation, and exhibit high levels of materialism. Generally, consumers motivated by economic factors are more likely to have a positive attitude towards SHC purchases. However, this relationship is significantly influenced by moderating effects, which may occasionally result in a negative association with SHC attitude. |

| H2 | Supported | The treasure hunting motivation is positively correlated with the attitude towards buying SHC. This motivation consistently shows positive associations when moderating variables are within one standard deviation around the mean, especially for consumers with above-average levels of personal liberty. The effect of treasure hunting motivation on SHC attitude tends to be stronger for those who value individual liberty and hold negative opinions about the government’s active role in society. |

| H3, H4, H5 | Supported | Factor analysis combined the initially assumed three constructs related to personal responsibility into one broader construct dubbed “responsibility.” This encompasses opposition to purchasing from companies using sweatshop labor, a deliberate choice to buy environmentally friendly clothes, and guilt associated with buying fast fashion. Personal responsibility is positively correlated with the attitude towards buying SHC, especially when its moderating variables at average levels. The positive effect can be enhanced for individuals who hold negative views on individual liberty and are in a favorable financial situation. This motivation is generally associated with a positive attitude towards SHC purchases, though moderating effects can occasionally lead to an unfavorable association. |

| H6 | Partially Supported | Materialistic centrality of acquisition significantly influences the model only when interacting with other variables, typically showing a negative relationship with the attitude towards buying SHC. This negative effect is amplified for those disinterested in fashion, not motivated by economic factors, in a favorable financial situation, and expressing other materialistic values. Generally, consumers valuing materialistic centrality of acquisition are more likely to have a negative attitude towards SHC, though moderating effects may lead to a positive association for some consumers. |

| H7, H8 | Partially Supported | The constructs related to materialistic possession-defined success and acquisition as the pursuit of happiness were combined into one. This construct, primarily related to acquisition as the pursuit of happiness, was significant in the model only when interacting with other variables and typically has a negative association. A more negative attitude is exhibited by individuals who are female, older, less educated, value individual liberty, and hold other dimensions of materialism. Generally, consumers motivated by these factors, influenced by other variables, will mostly have a negative attitude towards SHC purchases. However, moderating effects may result in a positive association in some cases. |

| H9 | Supported | Interest in fashion is negatively correlated with the attitude towards buying SHC when moderating variables are at average levels. This negative association is more pronounced for those who disagree with materialistic centrality of acquisition and hold negative views about the government’s role in society. Generally, consumers interested in fashion usually have a negative attitude towards SHC purchases, although sometimes moderating effects may lead to a positive association. |

| H10 | Partially Supported | The strength and direction of the association between political views on individual liberty and SHC attitude depends entirely on interactions with other terms. This relationship tends to be negative for those disagreeing with responsibility motivation, older individuals, and those holding negative views about the government’s role in society. |

| H11 | Partially Supported | The direction of this relationship with interactions depends entirely on the moderating effects, and it could be either negative or positive. For example, a significant positive effect was found, for males in an unfavorable financial situation, interested in fashion, and holding negative opinions about individual liberty. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Halicki, D.; Zaborek, P.; Meylan, G. Sustainable Fashion Choices: Exploring European Consumer Motivations behind Second-Hand Clothing Purchases. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 174. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14080174

Halicki D, Zaborek P, Meylan G. Sustainable Fashion Choices: Exploring European Consumer Motivations behind Second-Hand Clothing Purchases. Administrative Sciences. 2024; 14(8):174. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14080174

Chicago/Turabian StyleHalicki, Daniel, Piotr Zaborek, and Grégoire Meylan. 2024. "Sustainable Fashion Choices: Exploring European Consumer Motivations behind Second-Hand Clothing Purchases" Administrative Sciences 14, no. 8: 174. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14080174

APA StyleHalicki, D., Zaborek, P., & Meylan, G. (2024). Sustainable Fashion Choices: Exploring European Consumer Motivations behind Second-Hand Clothing Purchases. Administrative Sciences, 14(8), 174. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14080174